Abstract

We previously clarified that the chitinase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakaraensis KOD1 produces diacetylchitobiose (GlcNAc2) as an end product from chitin. Here we sought to identify enzymes in T. kodakaraensis that were involved in the further degradation of GlcNAc2. Through a search of the T. kodakaraensis genome, one candidate gene identified as a putative β-glycosyl hydrolase was found in the near vicinity of the chitinase gene. The primary structure of the candidate protein was homologous to the β-galactosidases in family 35 of glycosyl hydrolases at the N-terminal region, whereas the central region was homologous to β-galactosidases in family 42. The purified protein from recombinant Escherichia coli clearly showed an exo-β-d-glucosaminidase (GlcNase) activity but not β-galactosidase activity. This GlcNase (GlmATk), a homodimer of 90-kDa subunits, exhibited highest activity toward reduced chitobiose at pH 6.0 and 80°C and specifically cleaved the nonreducing terminal glycosidic bond of chitooligosaccharides. The GlcNase activity was also detected in T. kodakaraensis cells, and the expression of GlmATk was induced by GlcNAc2 and chitin, strongly suggesting that GlmATk is involved in chitin catabolism in T. kodakaraensis. These results suggest that T. kodakaraensis, unlike other organisms, possesses a novel chitinolytic pathway where GlcNAc2 from chitin is first deacetylated and successively hydrolyzed to glucosamine. This is the first report that reveals the primary structure of GlcNase not only from an archaeon but also from any organism.

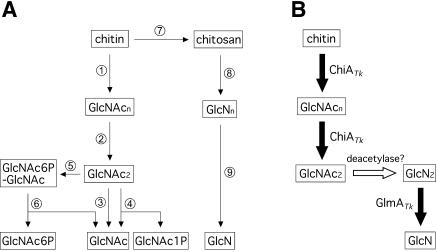

Chitin, an insoluble β-1,4-linked linear polymer of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), is the second most abundant organic compound on our planet after cellulose. Previously known biodegradation pathways of chitin are summarized in Fig. 1A. It is degraded into dimer units of GlcNAc (GlcNAc2) by the combination of endo- and exo-type chitinases (reactions 1 and 2). β-N-Acetylglucosaminidase (GlcNAcase; reaction 3) further hydrolyzes the dimer to form GlcNAc or releases GlcNAc from chitooligosaccharides (6). Some organisms degrade GlcNAc2 to GlcNAc and GlcNAc-1-phosphate by GlcNAc2 phosphorylase (reaction 4) (28) or convert the dimer to GlcNAc-6-phosphate-GlcNAc by a GlcNAc2 phosphotransferase system (reaction 5) followed by degradation to GlcNAc and GlcNAc-6-phosphate by 6-phospho-β-glucosaminidase (reaction 6) (15, 16). Another pathway for chitin degradation is proposed to occur through deacetylation of chitin by chitin deacetylase (reaction 7). The resulting deacetylated chitin, chitosan, is then degraded to glucosamine (GlcN) by chitosanase (endo-type enzyme [reaction 8]) in cooperation with exo-β-d-glucosaminidase (GlcNase; reaction 9) (6). In contrast to the many studies on chitinases, chitosanases, GlcNAcases, and chitin deacetylases, information concerning GlcNase has been quite limited (20, 22, 25, 36). Moreover, a gene encoding GlcNase has not yet been cloned from any source.

FIG. 1.

(A) Previously known chitin catabolic pathways from chitin to monosaccharides. Enzymes are displayed as 1, endochitinase; 2, exochitinase; 3, GlcNAcase; 4, GlcNAc2 phosphorylase; 5, GlcNAc2 phosphotransferase system; 6, 6-phospho-β-d-glucosaminidase; 7, chitin deacetylase; 8, chitosanase; and 9, GlcNase. (B) A novel chitin catabolic pathway proposed in T. kodakaraensis KOD1. Intermediates: GlcNAcn, N-acetylchitooligosaccharide; GlcNn, chitooligosaccharide; GlcNAc1P, GlcNAc 1-phosphate; GlcNAc6P-GlcNAc, GlcNAc-6-phosphate-GlcNAc; and GlcNAc6P, GlcNAc-6-phosphate.

We previously reported the first cloning and characterization of chitinase from an archaeon (32, 33). The chitinase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakaraensis KOD1 (previously reported as Pyrococcus kodakaraensis KOD1) possesses endo- and exo-type catalytic domains together with three chitin-binding domains on a single polypeptide. It has also been clarified that this chitinase (ChiATk) produces GlcNAc2 as an end product from chitin. However, the fate of GlcNAc2 in T. kodakaraensis remained to be solved. Interestingly, no gene homologous to any of the known GlcNAc2-processing enzymes (GlcNAcase, GlcNAc2 phosphorylase, and GlcNAc2 phosphotransferase system) could be identified in the preliminary complete genome sequence of strain KOD1. This is also the case for other archaeal genomes, including those of Pyrococcus furiosus and Halobacterium sp. strain NRC-1, both of which possess putative chitinase genes (3, 24). These facts suggested the existence of a novel type of enzyme or an unknown chitinolytic pathway in Archaea.

This study aimed to identify the enzymes involved in the downstream steps of chitinolysis after chitinase in T. kodakaraensis KOD1. Through a search of the T. kodakaraensis genome, we found a gene initially identified as a putative β-glycosyl hydrolase located near the chitinase gene and demonstrated that the gene product was a GlcNase. As a GlcNase gene has not yet been identified from any organism, including Archaea, we report the characterization of this GlcNase (GlmATk) and contemplate its contribution to a novel GlcNAc2 degradation pathway in the archaeon T. kodakaraensis (Fig. 1B).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmid, and medium.

Escherichia coli TG-1 and BL21-CodonPlus(DE3)-RIL were used as hosts for the expression plasmid derived from pET-25b(+) (Novagen, Madison, Wis.) and were cultivated in Luria-Bertani medium at 37°C. Ampicillin was added to the medium at a final concentration of 50 μg/ml when needed.

DNA manipulations and sequencing.

DNA manipulations were performed by standard methods, as described by Sambrook and Russell (30). Restriction enzymes and other modifying enzymes were purchased from Takara Shuzo (Kyoto, Japan) or Toyobo (Osaka, Japan). Small-scale preparation of plasmid DNA from E. coli cells was performed with the Qiagen plasmid minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). DNA sequencing was performed with BigDye terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kit version 3.0 and a model 3100 capillary DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.).

Construction of expression plasmid.

The expression plasmid for the GlcNase gene from T. kodakaraensis (glmATk) was constructed by PCR as described below. Two oligonucleotides (sense, 5′-GTGATGCATATGGGAAAGGTTGAGTTTAGCGGC-3′; antisense, 5′-GGGAATTCCCTCATCGTGGTTGCAGATCC-3′ [underlined sequences indicate an NdeI site in the sense primer and an EcoRI site in the antisense primer]) and KOD1 genomic DNA were used as the primers and template for DNA amplification, respectively. The amplified DNA was digested with NdeI and EcoRI and then ligated with the corresponding sites in plasmid pET-25b(+). The absence of unintended mutations in the insert was confirmed by DNA sequencing. The resulting plasmid was designated pET-glmA.

Purification of recombinant GlmATk.

E. coli BL21-CodonPlus(DE3)-RIL cells harboring pET-glmA were induced for overexpression with 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at the mid-exponential growth phase and incubated for a further 5 h at 37°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (5,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C) and then resuspended in buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA). The cells were disrupted by sonication, and the supernatant was obtained by centrifugation (14,000 × g for 30 min). The supernatant was incubated at 85°C for 30 min and centrifuged (14,000 × g for 30 min) to obtain a heat-stable protein solution. The resulting solution was applied to a Resource Q column (6 ml) (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) equilibrated with buffer A. GlmATk was eluted with a linear gradient of NaCl (0 to 0.4 M), and the peak fractions eluted at 0.3 M NaCl were concentrated with an Ultrafree-4 centrifugal filter unit Biomax-30 (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.). This was applied to a Superdex-200 HR 10/30 column (Amersham Biosciences) equilibrated with buffer B (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl). The peak fractions were dialyzed with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and stored at 4°C. The protein concentration was determined with the Bio-Rad protein assay system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) with bovine serum albumin as the standard. The N-terminal amino acid sequence of the protein was determined with a model 491 cLC protein sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

Analyses of reaction products.

The analyses of reaction products from chitooligosaccharides (GlcN2-6), N-acetylchitooligosaccharides (GlcNAc2-5), lactose, cellobiose, laminaribiose, chitosan 10B (Funakoshi, Tokyo, Japan), and colloidal chitin were performed by silica gel thin-layer chromatography (TLC) as described previously (32). When reaction products from reduced chitooligosaccharides (chitooligosaccharide alditols, GlcN2-5OH; these substrates were kindly donated by Yaizu Suisankagaku Industry, Shizuoka, Japan) were analyzed, propanol-25% ammonia (1:1 [vol/vol]) was used as a developer. Aniline-diphenylamine reagent was usually used to detect reducing sugars, while products from GlcN2-5OH were detected with the ninhydrin reagent (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan). The preparation of colloidal chitin has been described previously (32).

Enzyme assays.

GlcNase activity was assayed by a modification of the Schales procedure (12) with reduced chitobiose (GlcN2OH) as the substrate (final concentration, 2 mM). The pH dependency of GlmATk was determined at 70°C for 10 min with the following buffers: pH 4.0 to 5.5, 50 mM sodium acetate; pH 5.5 to 7.0, 50 mM 4-morpholinoethanesulfonic acid (MES)-NaOH; pH 7.0 to 9.0, 50 mM Tris-HCl. The optimal temperature for GlmATk was examined in a temperature range of 37°C to 100°C for 10 min in 50 mM MES-NaOH (pH 6.0). Specific activity toward chitosan 10B was determined with 0.8% substrate in 160 mM acetate-NaOH buffer at 80°C for 10 min.

To determine the kinetic properties of GlmATk toward GlcN2-6, the reactions were performed with various concentrations of GlcN2-6 (GlcN2, 0.1 to 4 mM; GlcN3, 0.05 to 1 mM; GlcN4, 0.05 to 2 mM; GlcN5, 0.05 to 0.5 mM; GlcN6, 0.05 to 2 mM) in 50 mM MES-NaOH (pH 6.0) at 80°C for 5 min. The concentration of the released GlcN was determined by a modified method of Morgan and Elson (5), where the length of the acetylation reaction with ice-cold 5% acetic anhydrate solution was modified from 3 min to 20 min. Various β-glycosyl hydrolase activities were measured in a fluorometric assay with 4-methylumbelliferyl N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminide, 4-methylumbelliferyl β-d-glucoside, 4-methylumbelliferyl β-d-galactoside, and 4-methylumbelliferyl N-acetyl-β-d-galactosaminide (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) as described previously (32). One unit corresponds to hydrolysis of 1 μmol of glycosidic bond per min.

Western blot analysis.

T. kodakaraensis KOD1 was grown anaerobically in 10 ml of MA medium (4.8 g and 26.4 g of Marine Art SF agents A and B, respectively [Senju Seiyaku, Osaka, Japan], 5 g of yeast extract, and 5 g of tryptone in 1 liter of deionized water) supplemented with 20 μl of polysulfide solution (20% elemental sulfur in 3 M Na2S) and various kinds of saccharides. The cells were harvested and disrupted by sonication in buffer A containing protein inhibitor mix (Complete Mini; Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland), and soluble fractions were obtained by centrifugation (15,000 × g for 30 min). Each fraction was subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and successive Western blot analysis with specific rabbit antiserum against the recombinant GlmATk. A protein A-peroxidase conjugate was used to visualize the specific protein together with 4-chloro-1-naphthol and hydrogen peroxide.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence data reported here are available in the EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ nucleotide sequence databases under accession number AB100422.

RESULTS

Search of candidate gene for GlcNAc2 catabolism in T. kodakaraensis KOD1 genome.

As previously reported, the genes for chitinase (chiATk) and β-glycosidase (glyTk) were located near each other in the T. kodakaraensis genome (Fig. 2, gray arrows) (4). We therefore examined the ability of GlyTk to hydrolyze GlcNAc2 and its deacetylated compound, GlcN2, because this enzyme has been determined to possess broad substrate specificity toward various β-linked sugars (4). However, the enzyme showed no activity toward GlcNAc2 and only faint activity toward GlcN2 (data not shown). In addition, a homology search with the sequences of known GlcNAc2-processing enzymes (GlcNAcase, GlcNAc2 phosphorylase, and GlcNAc2 phosphotransferase system) against the preliminary complete genome sequence of T. kodakaraensis did not lead to identification of any candidate gene.

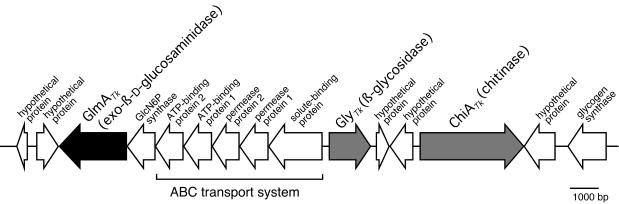

FIG. 2.

Gene organization in the 23.7-kbp region including glmATk on the T. kodakaraensis KOD1 genome. Arrows indicate open reading frames. Black arrow, GlmATk; gray arrows, GlyTk (β-glycosidase) (4) and ChiATk (32, 33); white arrows, open reading frames of uncharacterized proteins.

We then addressed the possibility that a gene(s) for an unknown β-glycosyl hydrolase involved in chitinolysis may be clustered together with chiATk and analyzed the region around chiATk in detail. This attempt led to the identification of one gene, homologous to the genes for putative β-galactosidases in the closely related genus Pyrococcus, located approximately 11 kbp upstream from chiATk in the opposite orientation (Fig. 2, black arrow). Since the gene turned out to encode a GlcNase, as described below, it was designated glmATk.

Primary structure of glmATk.

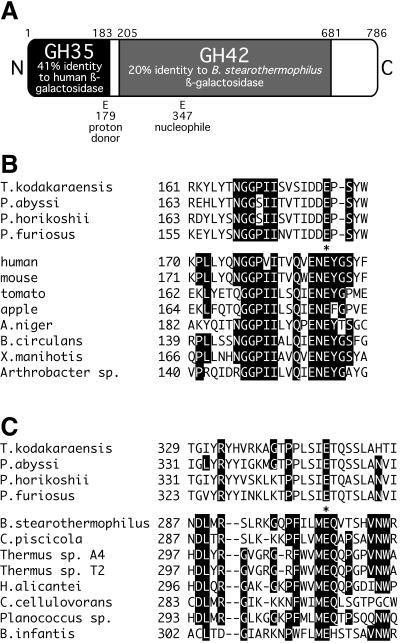

The glmATk gene consisted of 2,358 bp, encoding a protein of 786 amino acids with a predicted molecular mass of 90,227 Da. The deduced amino acid sequence showed high overall identities to putative archaeal β-galactosidases, PAB1349 from “Pyrococcus abyssi” (64% identity), PH0511 from Pyrococcus horikoshii (61% identity), and PF0363 from Pyrococcus furiosus (57% identity). As shown in Fig. 3, the N-terminal region, spanning a quarter of the protein, showed homology to β-galactosidases of family 35 glycosyl hydrolases (41% identity to human β-galactosidase), while the central region of about 480 amino acid residues showed weak homology to the β-galactosidases of family 42 glycosyl hydrolases (20% identity to β-galactosidase from Bacillus stearothermophilus). Both families are classified in the same superfamily, clan A of glycosyl hydrolases (http://afmb.cnrs-mrs.fr/CAZY/index.html), and their catalytic residues have been predicted by hydrophobic cluster analysis (8).

FIG. 3.

(A) Primary structural features of GlmATk. Black and gray regions indicate regions homologous to β-galactosidases in family 35 and family 42 glycosyl hydrolases (GH35 and GH42), respectively. Putative proton donor and nucleophilic residues are indicated. (B and C) Amino acid sequence alignments of regions surrounding putative proton donor residues of family 35 β-galactosidases (B) and putative nucleophilic residues of family 42 β-galactosidases (C) along with the archaeal homologues. Amino acid residues conserved in five out of eight β-galactosidases of families 35 and 42 and the corresponding residues in archaeal homologues are highlighted. Conserved glutamate residues that probably act as the proton donor and the nucleophile are indicated by asterisks. Accession numbers for these sequences are as follows: “P. abyssi,” CAB50440; P. horikoshii, BAA29599; P. furiosus, AAL80487; family 35 β-galactosidases from human (NP_000395 [27]), mouse (AAA37292 [21]), tomato (P48980 [1]), apple (T17002 [29]), Aspergillus niger (P29853 [19]), Bacillus circulans (JC5618 [13]), Xanthomonas manihotis (P48982 [34]), and Arthrobacter sp. (P96567 [7]); and family 42 β-galactosidases from Bacillus stearothermophilus (AAA22262 [9]), Carnobacterium piscicola (AAF16519 [2]), Thermus sp. strain A4 (BAA28362 [26]), Thermus sp. strain T2 (CAB07810 [35]), Haloferax alicantei (AAB40123 [10]), Clostridium cellulovorans (AAN05452 [18]), Planococcus sp. (AAF75984 [31]), and Bifidobacterium infantis (AAL02053 [11]).

GlmATk and its homologous archaeal proteins harbored the predicted catalytic proton donor and nucleophilic residues in the homologous regions of family 35 and family 42 glycosyl hydrolases, respectively (Fig. 3). However, highly conserved motifs around these catalytic residues (QXENEY around the putative proton donor in family 35 and FXXMEQ around the putative nucleophile in family 42) were not conserved (Fig. 3B and C). The C-terminal region of about 100 amino acid residues had no significant homology to other known enzymes besides the archaeal homologues. Typical signal peptides for secretion and transmembrane helices were not detected with the SOSUI transmembrane helix prediction software (sosui.proteome.bio.tuat.ac.jp/∼sosui/proteome/sosuiframe0.html).

Overexpression and purification of recombinant GlmATk.

To characterize the enzymatic properties of GlmATk, the recombinant protein was produced in E. coli cells with the pET expression system. The cells harboring the expression plasmid were induced with IPTG, and the recombinant protein was purified to apparent homogeneity in SDS-PAGE by heat treatment and column chromatographies, as described in Materials and Methods. Its N-terminal amino acid sequence was determined to be XKVEFSGKRY, suggesting elimination of the N-terminal Met residue (the predicted N-terminal amino acid sequence of GlmATk is MGKVEFSGKRYVID). The molecular mass of the recombinant GlmATk was estimated to be about 86 kDa by SDS-PAGE and 193 kDa by gel filtration chromatography. The results indicated that GlmATk was a homodimeric enzyme.

Substrate specificity of GlmATk.

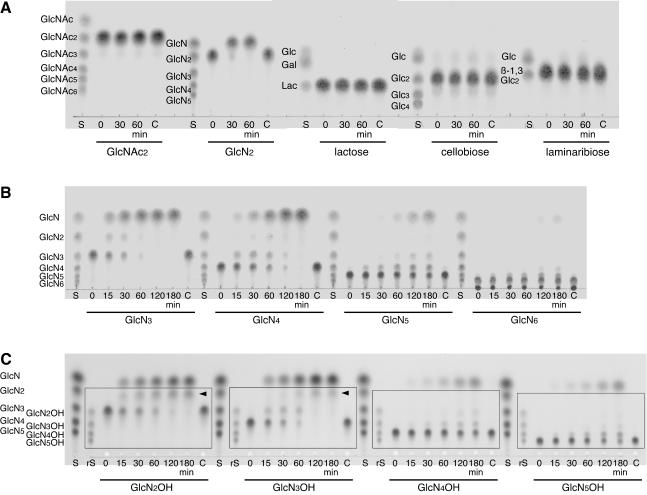

We then examined the hydrolytic activities of the purified recombinant GlmATk toward various β-disaccharides (GlcNAc2, GlcN2, lactose, cellobiose, and laminaribiose) as substrates. The reactions were monitored by TLC. As shown in Fig. 4A, GlmATk could hydrolyze neither lactose nor GlcNAc2, but a remarkable activity was observed toward GlcN2. This enzyme showed very weak hydrolytic activities toward cellobiose and laminaribiose in addition to the major GlcNase activity (Fig. 4A), and the β-glucosidase activity was also confirmed by fluorometric assay with 4-methylumbelliferyl β-d-glucoside as the substrate (1.77 × 10−2 U/mg). It should be noted that GlmATk could not hydrolyze 4-methylumbelliferyl β-d-galactoside, 4-methylumbelliferyl N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminide, or 4-methylumbelliferyl N-acetyl-β-d-galactosaminide (<1.00 × 10−5 U/mg). Although the primary structure of GlmATk showed homology with β-galactosidases, as described above, the results obtained here clearly indicated that GlmATk was a GlcNase, not a β-galactosidase.

FIG. 4.

Hydrolysis of various β-disaccharides (GlcNAc2, GlcN2, lactose [Lac], cellobiose [Glc2], and laminaribiose [β-1,3-Glc2]) (A), chitooligosaccharides (GlcN3-6) (B), and reduced chitooligosaccharides (GlcN2-5OH) (C) with various chain lengths by GlmATk. The reaction mixture (25 μl) containing 0.2 mg of the substrate and 25 pmol of GlmATk in 50 mM MES-NaOH (pH 5.0) was incubated at 70°C. The reaction products were analyzed at the indicated times. TLC plates were visualized with aniline-diphenylamine reagent (A and B) and with ninhydrin reagent (C). The spots undetectable with the aniline-diphenylamine reagent in C are boxed. The spots pointed to by arrowheads are probable reduced GlcN. Lanes C, control without GlmATk after each reaction; lanes S, various chain lengths of saccharides corresponding to the substrates used in each reaction; lanes rS, standard reduced chitooligosaccharides from GlcN2OH to GlcN5OH.

Enzymatic properties of GlmATk.

The optimal pH and temperature of GlmATk for reduced chitobiose (GlcN2OH) were 6.0 and 80°C, respectively. Activity levels at 37°C and 100°C were approximately 20% of that observed at the optimal temperature. For determination of the cleavage specificity of this enzyme, reaction products from various chain lengths of chitooligosaccharides (GlcN3-6) were analyzed with TLC (Fig. 4B). GlmATk showed hydrolytic activities toward all substrates examined, and at the early stages of the reactions, we detected spots corresponding to GlcN and oligosaccharides that were one unit shorter than the starting substrates. Subsequently, reduced chitooligosaccharides (GlcN2-5OH) were applied as substrates in order to distinguish the direction of the oligosaccharides. In this experiment, the products were visualized separately with ninhydrin reagent (Fig. 4C) in addition to aniline-diphenylamine reagent (data not shown) because reduced chitooligosaccharides could not be detected with the latter reagent. When aniline-diphenylamine reagent was used, the only spots detected were those corresponding to GlcN. This indicated that all spots boxed in Fig. 4C, visualized with ninhydrin reagent, were reduced oligosaccharides. These TLC analyses revealed that at the early stages of the reactions, the initial substrates were converted to GlcN and a one-unit-shorter reduced chitooligosaccharide. The spots indicated by arrowheads are presumably glucosaminitol (reduced GlcN). Apparently, GlmATk was an exo-type enzyme which specifically hydrolyzed the first glucosaminide bond from the nonreducing end of chitooligosaccharides.

We then determined the kinetic constants of GlmATk toward GlcN2-6 (Table 1). Among these substrates, GlmATk showed the highest Vmax and Km values toward GlcN2, while the lowest values were shown toward GlcN5. The kcat/Km ratios toward all substrates were comparable. GlmATk also released GlcN from chitosan polysaccharide (chitosan 10B, more than 98% deacetylated), but the specific activity (0.70 U/mg) was much lower than the Vmax toward the chitooligosaccharides (12 to 99 U/mg). In contrast to the broad specificity of these substrates for chain length, this enzyme never accepted the N-acetylated compounds colloidal chitin and GlcNAc2-5 as substrates regardless of their chain lengths (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Kinetic properties of GlmATk toward various chitooligosaccharidesa

| Substrate | Vmax (U/mg) | Km (mM) | kcat/Km (M−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GlcN2 | 98.7 ± 1.7 | 1.37 ± 0.06 | 1.08 × 105 |

| GlcN3 | 34.5 ± 2.6 | 0.270 ± 0.052 | 1.92 × 105 |

| GlcN4 | 41.7 ± 1.0 | 0.295 ± 0.021 | 2.12 × 105 |

| GlcN5 | 12.0 ± 0.2 | 0.0778 ± 0.0049 | 2.31 × 105 |

| GlcN6 | 35.1 ± 0.2 | 0.365 ± 0.005 | 1.45 × 105 |

GlcNase assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods.

Expression profiles of GlmATk in T. kodakaraensis.

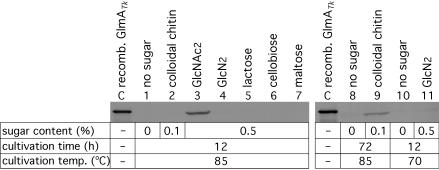

T. kodakaraensis was grown on various sugar-containing media, and the expression of GlmATk was examined by Western blot analysis (Fig. 5). When the organism was grown at 85°C for 12 h, the expression of GlmATk was induced only with the addition of GlcNAc2, an end product from chitin by the extracellular chitinase ChiATk (lane 3). Indeed, significant GlcNase activity toward GlcN2 was also detected in the extract from cells in the medium containing GlcNAc2 (data not shown). The detection of GlmATk protein and GlcNase activity within the cells also clarified that GlmATk is an intracellular enzyme, as suggested from the primary structure. In contrast to GlcNAc2, other disaccharides did not induce expression under these conditions (lanes 4 to 7). Expression of GlmATk could not be detected in the presence of colloidal chitin after 12 h (lane 2), and a similar lack of induction was also observed with the GlcNAc6 oligomer (data not shown). However, although to a lower extent, we clearly observed the induction of GlmATk by colloidal chitin after prolonged incubation for 72 h (lane 9). These results indicate that GlmATk expression can be induced under chitin degradation conditions through the intermediate, GlcNAc2.

FIG. 5.

Western blot analysis of cell extract of T. kodakaraensis KOD1 grown on various sugar-containing media. The sugar content in each medium, cultivation time, and cultivation temperature are indicated. The amounts of protein applied were 20 μg (KOD1 cell extract) or 50 ng (recombinant GlmATk, lane C).

When GlcN2 was added to the medium, serious browning of the medium was observed at 85°C, probably caused by a Maillard reaction of the amino sugar. In order to avoid the chemical reaction leading to the consumption of GlcN2, we examined the effect of GlcN2 on GlmATk expression at 70°C. Although slight browning of the medium was still observed at the lower cultivation temperature, approximately half of the initial GlcN2 remained in the medium even after cultivation. Nevertheless, no expression of GlmATk was observed under this condition (lane 11), indicating that GlcN2, although a substrate, was not an inducer of glmATk gene expression. Due to its lability to heat, a regulation system responding to GlcN2 may not have evolved in the hyperthermophilic T. kodakaraensis. These expression profiles of GlmATk against GlcNAc2 and colloidal chitin supported the participation of GlmATk in chitin catabolism in cooperation with ChiATk by T. kodakaraensis KOD1.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified a GlcNase gene from T. kodakaraensis KOD1 during our attempt to clarify the mechanism of archaeal chitin catabolism. This is the first report of a GlcNase gene not only from an archaeon but also from any organism.

The glmATk gene was initially identified as a putative β-glycosyl hydrolase gene located near chiATk (11 kbp upstream) on the T. kodakaraensis genome (Fig. 2). We estimated that this gene product participated in the archaeal chitinolytic pathway and indicated that the recombinant GlmATk indeed showed GlcNase activity. Furthermore, this activity could actually be detected in the cell extract of T. kodakaraensis. Although GlmATk can hydrolyze chitosan and chitooligosaccharides of various chain lengths, as described above, the deacetylated products of GlcNAc2 can be considered the physiological substrates in this organism for the following reasons. (i) The intracellular localization of GlmATk prevents its direct interaction with polysaccharides existing outside the cells. In addition, the specific activity of GlmATk for chitosan was much lower than those for chitooligosaccharides. (ii) ChiATk, harboring both endo- and exo-type catalytic domains, accumulated only GlcNAc2 as an end product in the hydrolysis of colloidal chitin, and longer oligomers could not be detected (32, 33). These facts strongly suggested that in the chitin catabolic pathway of T. kodakaraensis, the substrate of GlmATk is intracellular GlcN2. Furthermore, induction of GlmATk expression was observed after prolonged cultivation with chitin, and moreover, rapid induction occurred in the presence of GlcNAc2 but not with GlcN2. This implies that the generation of GlcN2 occurs via ChiATk-mediated degradation of chitin to GlcNAc2. Our observations also raise the possibility of the presence of a novel GlcNAc2 unit-specific deacetylase in T. kodakaraensis, to provide the substrate for GlmATk from GlcNAc2.

So far, among known organisms, chitin is degraded to dimer units by chitinases, followed by dimer processing with GlcNAcase, diacetylchitobiose phosphorylase, or GlcNAc2 phosphotransferase system and 6-phospho-β-glucosaminidase. Alternatively, chitin can be degraded by chitosanase and GlcNase after the initial deacetylation of chitin (Fig. 1A) (6, 15, 16, 28). In T. kodakaraensis KOD1, as in many organisms, chitin is first degraded into GlcNAc2 by ChiATk (32, 33), but the pathway downstream from GlcNAc2 was suggested to follow a distinct pathway, that is, deacetylation of GlcNAc2 by an uncharacterized deacetylase and successive hydrolysis to GlcN by GlmATk (Fig. 1B). To our knowledge, a chitin catabolic pathway of this kind has not yet been reported and may be a novel pathway functioning in archaeal cells.

Until now, there have been only four reports on GlcNases. They have been identified from an actinomycete (Nocardia orientalis [22]) and fungi (Trichoderma reesei [25], Penicillium funiculosum [20], and Aspergillus oryzae [36]). As the corresponding genes have not been isolated, there is no information on their primary structures. The properties of these GlcNases and GlmATk are summarized in Table 2. These GlcNases cleave the nonreducing terminal glycosyl bond of chitooligosaccharides. Significant differences between GlmATk and the others were observed in terms of their subunit assembly and their localization. GlmATk was dimeric and an intracellular enzyme, while the other GlcNases were monomeric and extracellular enzymes. Therefore, GlmATk may not be related to the other GlcNases with respect to primary structure. The optimum temperature for GlmATk was the highest among these GlcNases.

TABLE 2.

Properties of GlcNases

| Origin of GlcNase | Optimum pH | Optimum temp (°C) | Cleavage site | Mol mass (kDa), SDS-PAGE/ gel filtration | Subunit assembly | Localization | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermococcus kodakaraensis | 6.0 | 80 | Nonreducing end | 86/193 | Dimer | Intracellular | This study |

| Nocardia orientalis | 5.5 | 60 | Nonreducing end | 70/97 | Monomer | Extracellular | 22 |

| Trichoderma reesei | 4.0 | 50 | Nonreducing end | 93/92 | Monomer | Extracellular | 25 |

| Penicillium funiculosum | 4.0 | 60-70 | Nonreducing end | 108/108 | Monomer | Extracellular | 20 |

| Aspergillus oryzae | 5.5 | 50 | Not determined | 135/135 | Monomer | Extracellular | 36 |

The three archaeal proteins from Pyrococcus spp. that were homologous to GlmATk were originally assigned as putative β-galactosidases because the N-terminal and central regions in these proteins showed homologies toward family 35 and 42 β-galactosidases, respectively. Although these archaeal proteins also harbored the two putative catalytic glutamate residues conserved in these β-galactosidases, highly conserved motifs around these catalytic residues were not conserved, as described in Results (Fig. 3). An unrooted phylogenetic tree clearly showed that GlmATk and the putative archaeal β-galactosidases were positioned far from either the family 35 or 42 β-galactosidases. It has also been reported that the putative β-galactosidase from P. furiosus (PF0363) did not possess β-galactosidase activity toward a chromogenic substrate (14). In light of these results, the putative archaeal β-galactosidases can be predicted to be not β-galactosidases but GlcNases, as demonstrated in this study.

The glmATk gene was clustered with genes of a putative glucosamine-6-phosphate (GlcN6P) synthase and a putative ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transport system in the same direction on the T. kodakaraensis genome (Fig. 2). The transcription of these genes was estimated to be polycistronic because the flanking genes overlapped or were located within short interval regions (from −8 bp to 47 bp). The genes for previously studied chitinase and β-glycosidase were located in the region upstream of the putative ABC transport system in an opposite orientation. ChiATk is an extracellular enzyme, but GlmATk was found within the cell, which indicates that GlcNAc2 produced by ChiATk (or its deacetylated product) must be translocated across the cellular membrane to be further degraded. The putative ABC transport system found in the gene cluster (Fig. 2) may function as the amino disaccharide transporter. Generally, GlcN is converted to fructose-6-phosphate (Fru6P) via GlcN6P by phosphorylation and isomerization along with deamination (23). The resulting Fru6P is catabolized by the glycolytic pathway. It has been reported that glucokinases from P. furiosus and Thermococcus litoralis can phosphorylate GlcN as well as glucose (17), and a gene homologous to these glucokinases is also present on the T. kodakaraensis genome (73% and 57% identity, respectively) at a different locus. GlcN6P synthase is an enzyme that converts Fru6P into GlcN6P, and there are two genes encoding products resembling this synthase on the genome. One of the genes for the synthase was located adjacently upstream of glmATk as described above (Fig. 2), raising the possibility that this gene product may be involved in the catabolism of GlcN produced from chitin.

Along with the first gene isolation of a β-glucosaminidase, the present study proposes the presence of a novel chitin catabolic pathway in Archaea (Fig. 1B). In order to confirm this pathway, isolation of GlcNAc2 deacetylase as a key link between the already characterized enzymes is indispensable and is now under way.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Japan Science and Technology Corporation (JST) for Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology (CREST) to T.I. and by a Grant-in-Aid from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) fellows to T.T. from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carey, A. T., K. Holt, S. Picard, R. Wilde, G. A. Tucker, C. R. Bird, W. Schuch, and G. B. Seymour. 1995. Tomato exo-(1→4)-β-d-galactanase. Isolation, changes during ripening in normal and mutant tomato fruit, and characterization of a related cDNA clone. Plant Physiol. 108:1099-1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coombs, J. M., and J. E. Brenchley. 1999. Biochemical and phylogenetic analyses of a cold-active β-galactosidase from the lactic acid bacterium Carnobacterium piscicola BA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:5443-5450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Driskill, L. E., K. Kusy, M. W. Bauer, and R. M. Kelly. 1999. Relationship between glycosyl hydrolase inventory and growth physiology of the hyperthermophile Pyrococcus furiosus on carbohydrate-based media. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:893-897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ezaki, S., K. Miyaoku, K. Nishi, T. Tanaka, S. Fujiwara, M. Takagi, H. Atomi, and T. Imanaka. 1999. Gene analysis and enzymatic properties of thermostable β-glycosidase from Pyrococcus kodakaraensis KOD1. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 88:130-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghosh, S., H. J. Blumenthal, E. Davidson, and S. Roseman. 1960. Glucosamine metabolism. V. Enzymatic synthesis of glucosamine 6-phosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 235:1265-1273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gooday, G. W. 1994. Physiology of microbial degradation of chitin and chitosan, p. 279-312. In C. Ratledge (ed.), Biochemistry of microbial degradation. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- 7.Gutshall, K., K. Wang, and J. E. Brenchley. 1997. A novel Arthrobacter β-galactosidase with homology to eukaryotic β-galactosidases. J. Bacteriol. 179:3064-3067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henrissat, B., I. Callebaut, S. Fabrega, P. Lehn, J. P. Mornon, and G. Davies. 1995. Conserved catalytic machinery and the prediction of a common fold for several families of glycosyl hydrolases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:7090-7094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirata, H., T. Fukazawa, S. Negoro, and H. Okada. 1986. Structure of a β-galactosidase gene of Bacillus stearothermophilus. J. Bacteriol. 166:722-727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmes, M. L., and M. L. Dyall-Smith. 2000. Sequence and expression of a halobacterial β-galactosidase gene. Mol. Microbiol. 36:114-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hung, M. N., Z. Xia, N. T. Hu, and B. H. Lee. 2001. Molecular and biochemical analysis of two β-galactosidases from Bifidobacterium infantis HL96. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4256-4263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imoto, T., and K. Yagishita. 1971. A simple activity measurement of lysozyme. Agric. Biol. Chem. 35:1154-1156. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ito, Y., and T. Sasaki. 1997. Cloning and characterization of the gene encoding a novel β-galactosidase from Bacillus circulans. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 61:1270-1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaper, T., C. H. Verhees, J. H. Lebbink, J. F. van Lieshout, L. D. Kluskens, D. E. Ward, S. W. Kengen, M. M. Beerthuyzen, W. M. de Vos, and J. van der Oost. 2001. Characterization of β-glycosylhydrolases from Pyrococcus furiosus. Methods Enzymol. 330:329-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keyhani, N. O., and S. Roseman. 1997. Wild-type Escherichia coli grows on the chitin disaccharide, N,N′-diacetylchitobiose, by expressing the cel operon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:14367-14371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keyhani, N. O., L. X. Wang, Y. C. Lee, and S. Roseman. 2000. The chitin disaccharide, N,N′-diacetylchitobiose, is catabolized by Escherichia coli and is transported/phosphorylated by the phosphoenolpyruvate:glycose phosphotransferase system. J. Biol. Chem. 275:33084-33090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koga, S., I. Yoshioka, H. Sakuraba, M. Takahashi, S. Sakasegawa, S. Shimizu, and T. Ohshima. 2000. Biochemical characterization, cloning, and sequencing of ADP-dependent (AMP-forming) glucokinase from two hyperthermophilic archaea, Pyrococcus furiosus and Thermococcus litoralis. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 128:1079-1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kosugi, A., K. Murashima, and R. H. Doi. 2002. Characterization of two noncellulosomal subunits, ArfA and BgaA, from Clostridium cellulovorans that cooperate with the cellulosome in plant cell wall degradation. J. Bacteriol. 184:6859-6865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar, V., S. Ramakrishnan, T. T. Teeri, J. K. Knowles, and B. S. Hartley. 1992. Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells secreting an Aspergillus niger β-galactosidase grow on whey permeate. Bio/Technology (N.Y.) 10:82-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsumura, S., E. Yao, and K. Toshima. 1999. One-step preparation of alkyl-β-d-glucosaminide by the transglycosylation of chitosan and alcohol using purified exo-β-d-glucosaminidase. Biotechnol. Lett. 21:451-456. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nanba, E., and K. Suzuki. 1990. Molecular cloning of mouse acid β-galactosidase cDNA: sequence, expression of catalytic activity and comparison with the human enzyme. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 173:141-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nanjo, F., R. Katsumi, and K. Sakai. 1990. Purification and characterization of an exo-β-d-glucosaminidase, a novel type of enzyme, from Nocardia orientalis. J. Biol. Chem. 265:10088-10094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Natarajan, K., and A. Datta. 1993. Molecular cloning and analysis of the NAG1 cDNA coding for glucosamine-6-phosphate deaminase from Candida albicans. J. Biol. Chem. 268:9206-9214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ng, W. V., S. P. Kennedy, G. G. Mahairas, B. Berquist, M. Pan, H. D. Shukla, S. R. Lasky, N. S. Baliga, V. Thorsson, J. Sbrogna, S. Swartzell, D. Weir, J. Hall, T. A. Dahl, R. Welti, Y. A. Goo, B. Leithauser, K. Keller, R. Cruz, M. J. Danson, D. W. Hough, D. G. Maddocks, P. E. Jablonski, M. P. Krebs, C. M. Angevine, H. Dale, T. A. Isenbarger, R. F. Peck, M. Pohlschroder, J. L. Spudich, K. H. Jung, M. Alam, T. Freitas, S. Hou, C. J. Daniels, P. P. Dennis, A. D. Omer, H. Ebhardt, T. M. Lowe, P. Liang, M. Riley, L. Hood, and S. DasSarma. 2000. Genome sequence of Halobacterium species NRC-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:12176-12181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nogawa, M., H. Takahashi, A. Kashiwagi, K. Ohshima, H. Okada, and Y. Morikawa. 1998. Purification and characterization of exo-β-d-glucosaminidase from a cellulolytic fungus, Trichoderma reesei PC-3-7. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:890-895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohtsu, N., H. Motoshima, K. Goto, F. Tsukasaki, and H. Matsuzawa. 1998. Thermostable β-galactosidase from an extreme thermophile, Thermus sp. A4: enzyme purification and characterization, and gene cloning and sequencing. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 62:1539-1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oshima, A., A. Tsuji, Y. Nagao, H. Sakuraba, and Y. Suzuki. 1988. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of cDNA for human β-galactosidase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 157:238-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park, J. K., N. O. Keyhani, and S. Roseman. 2000. Chitin catabolism in the marine bacterium Vibrio furnissii. Identification, molecular cloning, and characterization of a N,N′-diacetylchitobiose phosphorylase. J. Biol. Chem. 275:33077-33083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ross, G. S., T. Wegrzyn, E. A. MacRae, and R. J. Redgwell. 1994. Apple β-galactosidase. Activity against cell wall polysaccharides and characterization of a related cDNA clone. Plant Physiol. 106:521-528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 31.Sheridan, P. P., and J. E. Brenchley. 2000. Characterization of a salt-tolerant family 42 β-galactosidase from a psychrophilic antarctic Planococcus isolate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2438-2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanaka, T., S. Fujiwara, S. Nishikori, T. Fukui, M. Takagi, and T. Imanaka. 1999. A unique chitinase with dual active sites and triple substrate binding sites from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus kodakaraensis KOD1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:5338-5344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanaka, T., T. Fukui, and T. Imanaka. 2001. Different cleavage specificities of the dual catalytic domains in chitinase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakaraensis KOD1. J. Biol. Chem. 276:35629-35635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taron, C. H., J. S. Benner, L. J. Hornstra, and E. P. Guthrie. 1995. A novel β-galactosidase gene isolated from the bacterium Xanthomonas manihotis exhibits strong homology to several eukaryotic β-galactosidases. Glycobiology 5:603-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vian, A., A. V. Carrascosa, J. L. García, and E. Cortés. 1998. Structure of the β-galactosidase gene from Thermus sp. strain T2: expression in Escherichia coli and purification in a single step of an active fusion protein. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2187-2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang, X. Y., A. L. Dai, X. K. Zhang, K. Kuroiwa, R. Kodaira, M. Shimosaka, and M. Okazaki. 2000. Purification and characterization of chitosanase and exo-β-d-glucosaminidase from a koji mold, Aspergillus oryzae IAM2660. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 64:1896-1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]