Abstract

Flagellar hook-basal body (HBB) complexes were purified from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. The HBB was more acid labile but more heat stable than that of Salmonella species, and protein identification revealed that HBB components were expressed only from one of the two sets of flagellar gene clusters on the R. sphaeroides genome, under the heterotrophic growth conditions tested here.

Rhodobacter sphaeroides is a freshwater photosynthetic bacterium. Each cell has a single subpolar flagellum (2). Isolation of intact flagella from R. sphaeroides has previously been attempted (4, 14, 15) and revealed unique features of flagellar substructures distinguishable from those of other bacteria: straight hooks and bulky hook-associated protein (HAP) region. Biochemical analysis has been hampered by the low yield of pure samples. Here, we show a high-yield method for purification of the hook-basal body (HBB) complexes from R. sphaeroides and their biochemical analysis. We discuss these data in light of the organization and duplication of flagellar genes on the R. sphaeroides genome.

Temperature is most important for full flagellation of R. sphaeroides cells.

Photoheterotrophically grown R. sphaeroides cells most actively swim at the late log phase and then lose motility in the stationary phase. The loss of motility is accompanied by the loss of flagella. We therefore tested for optimal growth conditions for motility and thus flagellation.

Neither strong light illumination nor synthetic media (e.g., Sistrom's) were necessary for cells to be motile, but the incubation temperature was crucial. Cultures grown in Luria-Bertani medium with gentle agitation at 25 to 27°C gave more than 90% motility at the late log to early stationary phase.

Structural features of the purified HBB.

Intact flagella from R. sphaeroides cells were purified by our original protocol (1) with modifications. After lysis of spheroplasts with Triton X-100 and DNase treatment, the pH of the lysate was raised to 12, polyethylene glycol was added to 2%, and resulting bundles of flagella were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 0.2 M KCl-OH buffer (pH 12). The sample was further purified by CsCl density gradient centrifugation and resuspended in TET (1).

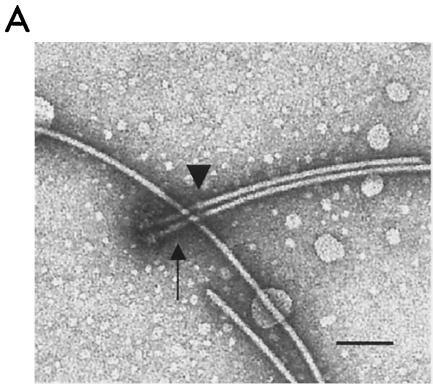

These intact flagella were negatively stained with 2% phosphotungstic acid and observed with a JEM-1200EXII electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). The hook characteristically appears straight between pH 4 and 9 (Fig. 1, arrows). Another example of a straight hook is found in the Na-driven polar flagellum of Vibrio alginolyticus. However, these cases are uncommon; flagella from the polar monoflagellates Caulobacter crescentus and Sinorhizobium meliloti have curved hooks.

FIG. 1.

Electron micrograph of intact flagella purified by the modified method. Shown are two flagella aligned side by side (A) and a larger image of the basal structure (B). The hook (arrows) is straight. The HAP region (arrowheads) extends beyond the thickness of the filament and hook. Bars, 100 nm.

The HAP region appeared larger than that of Salmonella species (15) (Fig. 1, arrowheads), correlating with R. sphaeroides genome sequence data that show one HAP component, FlgK, consisting of 1,363 amino acids (aa), versus the 552-aa Salmonella FlgK. Differences in the molecular size might explain the enlargement of the HAP region in the filament.

The R. sphaeroides HBB is acid labile but heat stable.

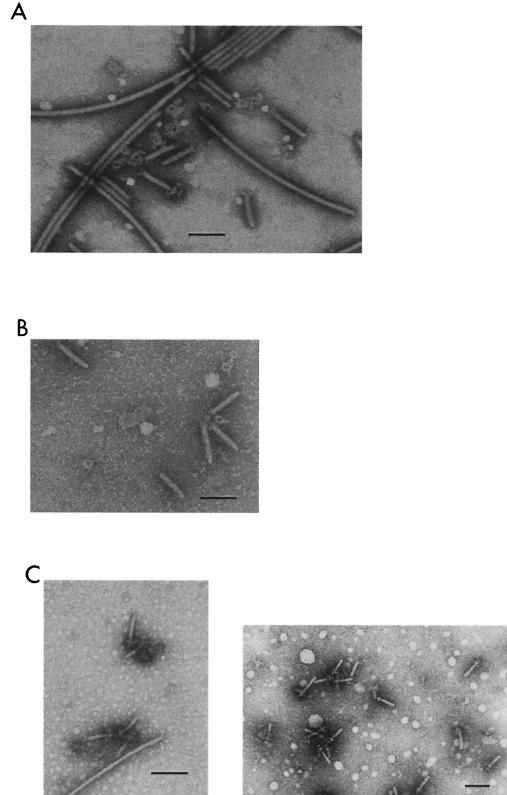

Acid depolymerization of filaments to yield pure HBBs, as previously employed for Salmonella species (1) and Bacillus subtilis (8), was tested on R. sphaeroides flagella. Incubation of intact flagella in acidic glycine buffer for 1 h gave rise to faster decomposition of the R. sphaeroides basal body than of the filament and hook. At pH 3.3, the basal bodies started decomposing into their component parts, releasing PL ring complexes from the hook and filament (Fig. 2A). At pH 3.2, filaments and rods disappeared, leaving hooks and rings only (Fig. 2B). Therefore, acid treatment is inadequate for isolation of R. sphaeroides HBB, and heat treatment was tried next.

FIG. 2.

Electron micrographs of partial structure of HBB. The stability of flagella against acid and heat was tested at pH 3.3 (A), pH 3.2 (B), and 55°C (C). Bars, 100 nm.

Incubation of intact flagella in TET buffer at 55°C resulted in the selective dissociation of filaments. After 30 min, filaments completely disappeared, leaving the HBB intact (Fig. 2C). At 60°C, the HBB was degraded into rings.

Identification of HBB component proteins.

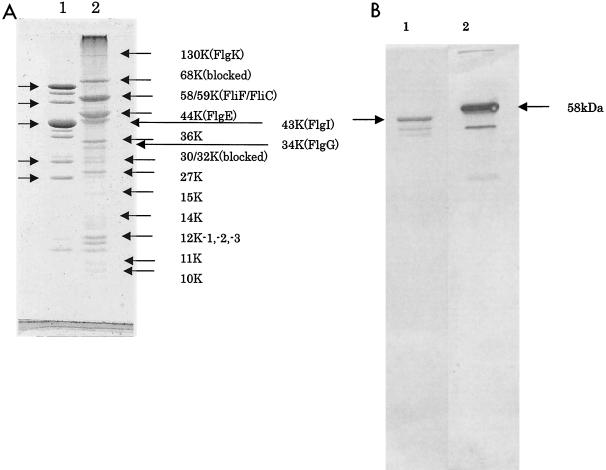

The HBBs obtained by 55°C heat treatment were visualized by Coomassie blue staining of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels (9). Eighteen bands were visualized with apparent molecular masses of 130, 68, 59, 58, 44, 43, 36, 34, 32, 30, 27, 15, 14, 12 (triplets), 11, and 10 kDa, by using Salmonella HBB proteins as a standard (Fig. 3A). Major proteins were sequenced for 5 to 10 aa from their N termini.

FIG. 3.

(A) SDS gel showing the component proteins of HBB purified from R. sphaeroides. Lane 1, Salmonella HBB as molecular mass protein markers (arrows indicate 65, 58, 42, 30, and 27 kDa from top to bottom); lane 2, R. sphaeroides HBB (each band was assigned by apparent molecular size and proteins if identified). (B) Western blotting with anti-FliF antibody. Lane 1, Salmonella HBB was probed with polyclonal anti-R. sphaeroides FliC antibody, and the arrow indicates flagellin; lane 2, R. sphaeroides HBB was reacted with anti-R. sphaeroides FliF antibody, and the arrow indicates FliF. Minor bands are nonspecific.

There are three sources of information regarding R. sphaeroides genes: the SWISS-PROT, National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), and DOE Joint Genome Institute (DJGI) data banks. The draft genome sequences generated by the DJGI are being annotated in collaboration with Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the University of Texas Department of Microbiology (10). The genome sequenced is that of R. sphaeroides 241, a close relative of the strain WS8 used in this study. More than one copy of many flagellar gene homologues is found on the R. sphaeroides genome. Table 1 shows a summary of the genes identified as expressing the flagellar proteins produced by R. sphaeroides in our experimental conditions.

TABLE 1.

Component proteins of R. sphaeroides HBB

| Protein name (substructure) | Size (aa) | Measured molecular mass (kDa) | N-terminal sequence | R. sphaeroides gene no.c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FlgK (HAP1) | 1363 | 130 | NDa | RSP074 |

| FliF (MS ring) | 570 | 58 | APSPTPP | RSP0053 |

| FliC (filament) | 493 | 59 | TTINTNI | RSP0069 |

| FlgE (hook) | 423 | 44 | SINTALSGLS | RSP0080 |

| FlgI (P ring) | 371 | 43 | DRLKDLT | RSP0076 |

| FlgG (distal rod) | 262 | 34 | TNAMVVA | RSP0078 |

| FlgF (rod) | 251 | 27 | ND | RSP0078 |

| FlgH (L ring) | 222 | 30 | Blockedb | RSP077 |

| FlgC (rod) | 139 | 15 | ND | RSP0082 |

| FlgB (rod) | 128 | 14 | ND | RSP0083 |

| FliE (rod) | 107 | 11 | ND | RSP0052 |

(i) Flagellin (FliC).

The flagellar filament of R. sphaeroides is composed of a 59-kDa flagellin (Fig. 3B, lane 2). The sequence of the N-terminal 7 aa corresponds to the translation of our previous fliC sequence (13) and that of the sole copy of R. sphaeroides fliC (RSP0069) (Table 1).

(ii) Hook protein (FlgE).

The hook protein ran as a 44-kDa band (Fig. 3B, lane 2). There are at least two flgE genes (RSP1303 and RSP0080) on the chromosome (3), and the sequence of the N terminus corresponded to that of RSP0080 (Table 1).

(iii) HAP1 (FlgK).

NCBI FlgK is a large protein with a predicted molecular mass of 133 kDa (1,363 aa). Prolonged incubation of sheared flagella at pH 3.3 gave rise to partial degradation of filaments, leaving the hook-HAP region-short filament complexes (data not shown). Such a sample gave three bands in an SDS gel: two thick bands of flagellin and hook protein and one faint band at 130 kDa corresponding to FlgK (Fig. 3B, lane 2).

The DJGI data bank includes two flgK genes: RSP1304 and RSP074. The FlgK N-terminal sequence was not determined, but it is likely that FlgK is encoded by RSP074 as this clusters with other flgI and flgG genes (see below) whose expression in the HBB was confirmed by N-terminal sequencing.

(iv) MS ring protein (FliF).

The MS ring complex is composed of the single protein FliF. There are two fliF genes in RSP1312 and RSP0053. RSP0053 was insertionally inactivated in R. sphaeroides WS8, producing a nonflagellate strain (5). A 58-kDa band in our gel was closest to the predicted molecular mass for the RSP0053 gene product and often overlapped with the 59-kDa flagellin band. Western blotting with anti-R. sphaeroides FliF antibody showed a stained band at 58 kDa (Fig. 3B). The sequence of the 58-kDa band corresponds to that of the RSP0053 gene.

(v) P ring protein (FlgI).

The N-terminal sequence of the 43-kDa band corresponds to the sequence from the 20th amino acid of NCBI FlgI (371 aa). In agreement with this, the N-terminal region of Salmonella FlgI is also cleaved at the 20th amino acid (6). The DJGI data bank includes two flgI genes: RSP0076 and RSP1307. The protein encoded by RSP0076 is identical with that of NCBI FlgI.

(vi) L ring protein (FlgH).

The Salmonella L ring is composed of FlgH, which is N-terminally blocked by lipoyl modification (12). The 30-kDa protein of the R. sphaeroides HBB was N-terminally blocked and could not be sequenced, suggesting that the 30-kDa protein could be FlgH. There are two candidates for flgH: RSP0077 and RSP1324. It is likely to be RSP0077 from its position being adjacent to the expressed flgI gene (RSP0076) mentioned above.

(vii) Distal rod protein (FlgG).

Acid treatment (pH 3.2) of intact flagella resulted in decomposition of the HBB into its parts, mainly rings and hooks. This preparation gave three bands in an SDS gel: one strong band at 44 kDa of the hook protein and two weak bands at 36 and 34 kDa. The N-terminal sequence of the 34-kDa protein (TNAMVVA) resembles that of FlgG (262 aa) from gene RSP0078 (MSTNAMHVAS) and not the second gene copy on RSP1326.

(viii) Proximal rod proteins.

Since components of the other HBB substructures had been assigned to bands in SDS gels, the remainder should comprise the proximal rod (11). In Salmonella species this has four components: FlgB, FlgC, FlgF, and FliE (6, 10). Corresponding proteins of R. sphaeroides were tentatively assigned to rod components, and their molecular masses were deduced from DJGI as follows: 27 (FlgF), 15 (FlgC), 14 (FlgB), and 11 (FliE) kDa. Although this assignment is most likely, it is desirable to confirm it by other methods. Using the evidence of expression of clustered genes confirmed by N-terminal sequence above, we would suggest that genes RSP0079, RSP0082, RSP083, and RSP052 encode FlgF, FlgC, FlgB, and FliE, respectively.

(ix) Contaminating proteins.

A major contaminating protein in the HBB preparation was the 68-kDa band (Fig. 3A, lane 2). The protein was N-terminally blocked and not sequenced. No homologous proteins were found for another 36-kDa band with the N-terminal sequence DSPAVRVEAE. Three bands at 12 kDa seemed to be linked; when one appeared, all three did. Since one of them (12 kDa-1) was found to be a 50S ribosomal protein, the others could be also ribosomal proteins.

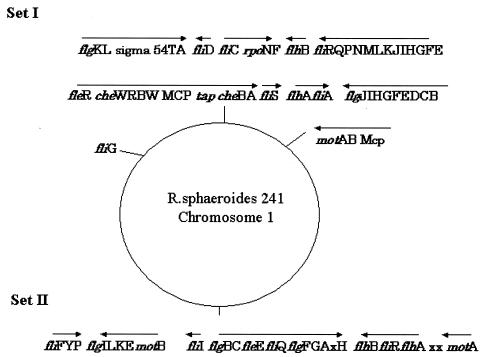

Organization and expression of flagellar genes in R. sphaeroides.

Each SDS gel band was assigned to a flagellar protein as in Fig. 3A. The positions of R. sphaeroides flagellar genes are summarized in Fig. 4. R. sphaeroides cells have two chromosomes: chromosome I (CI, 3.0 Mbp) and chromosome II (CII, 0.9 Mbp). All flagellar genes reside in CI only and are distributed into several clusters designated set I or set II. According to our biochemical analysis in this study, the component proteins of the HBB were translated from set I but not set II. Thus, genes in set II may be mostly pseudogenes or they may be genes that are expressed only under alternative growth conditions (10). The organization of the “set I flagellar genes” of the R. sphaeroides genome certainly shows similarities to that seen for the entire single set of flagellar genes from Escherichia coli. The arrangement of the set II flagellar genes is disorganized and fragmentary.

FIG. 4.

Physical map summarizing the position of R. sphaeroides flagellar genes. Details may be found in the data bank of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory KEGG Analysis for DJGI (http://genome.ornl.gov/microbial/rsph/1/kegg_fc.html).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Yukiko Nakauchi, Ayumi Ishi, Takuya Gotoh, and Kenta Yamaguchi for their technical help. We also thank Judy Armitage for information on genomes.

This work was supported by grants to S.-I.A. from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan and by grants to R.E.S. from the BBSRC and the Leverhulme Trust and to R.E.S. and D.S.H.S. from the Royal Society UK.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aizawa, S.-I., G. E. Dean, C. J. Jones, R. M. Macnab, and S. Yamaguchi. 1985. Purification and characterization of the flagellar hook-basal body complex of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 161:836-849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armitage, J. P., and R. M. Macnab. 1987. Unidirectional intermittent rotation of the flagellum of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 169:514-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballado, T., L. Camarena, B. Gonzalez-Pedrajo, E. Silva-Herzog, and G. Dreyfus. 2001. The hook gene (flgE) is expressed from the flgBCDEF operon in Rhodobacter sphaeroides: study of an flgE mutant. J. Bacteriol. 183:1680-1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gonzalez-Pedrajo, B., T. Ballado, A. Campos, R. E. Sockett, L. Camarena, and G. Dreyfus. 1997. Structural and genetic analysis of a mutant of Rhodobacter sphaeroides WS8 deficient in hook length control. J. Bacteriol. 179:6581-6588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodfellow, I. G. P.1996. Ph.D. thesis. University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom.

- 6.Jones, C. J., R. M. Macnab, H. Okino, and S.-I. Aizawa. 1990. Stoichiometric analysis of the flagellar hook-(basal-body) complex of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Mol. Biol. 212:377-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kubori, K., N. Shimamoto, S. Yamaguchi, K. Namba, and S.-I. Aizawa. 1992. Morphological pathway of flagellar assembly in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Mol. Biol. 226:433-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kubori, T., M. Okumura, N. Kobayashi, D. Nakamura, M. Iwakura, and S.-I. Aizawa. 1997. Purification and characterization of the flagellar hook-basal body complex of Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 24:399-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mackenzie, C., M. Choudhary, F. W. Larimer, P. F. Predki, S. Stilwagen, J. P. Armitage, R. D. Barber, T. J. Donohue, J. P. Hosler, J. E. Newman, J. P. Shapleigh, R. E. Sockett, J. Zeilstra-Ryalls, and S. Kaplan. 2001. The home stretch, a first analysis of the nearly completed genome of Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. Photosynth. Res. 70:19-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okino, H., M. Isomura, S. Yamaguchi, Y. Magariyama, S. Kudo, and S.-I. Aizawa. 1989. Release of flagellar filament-hook-rod complex by a Salmonella typhimurium mutant defective in the M ring of the basal body. J. Bacteriol. 171:2075-2082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schoenhals, G. L., and R. M. Macnab. 1996. Physiological and biochemical analysis of FlgH, a lipoprotein forming the outer membrane L ring of the flagellar basal body of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 178:4200-4207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shah, D. S. H., T. Perehinec, S. M. Stevens, S. I. Aizawa, and R. E. Sockett. 2000. The flagellar filament of Rhodobacter sphaeroides: pH-induced polymorphic transitions and analysis of the fliC gene. J. Bacteriol. 182:5218-5224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sockett, R. E., and J. P. Armitage. 1991. Isolation, characterization, and complementation of a paralyzed flagellar mutant of Rhodobacter sphaeroides WS8. J. Bacteriol. 173:2786-2790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.West, M. A., and G. Dreyfus. 1997. Isolation and ultrastructural study of the flagellar basal body complex from Rhodobacter sphaeroides WS8 (wild type) and polyhook mutant PG. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 238:733-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]