Abstract

To determine the cell compartment in which initial oncogenic mutations occur in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), we generated a mouse model in which endogenous expression of mutated Kras (KrasG12D) was initially directed to a population of pancreatic exocrine progenitors characterized by the expression of Nestin. Targeting of oncogenic Kras to such a restricted cell compartment was sufficient for the formation of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasias (PanINs), putative precursors to PDAC. PanINs appeared with the same grade and frequency as observed when KrasG12D was targeted to the whole pancreas by a Pdx1-driven Cre recombinase strategy. Thus, the Nestin cell lineage is highly responsive to Kras oncogenic activation and may represent the elusive progenitor population in which PDAC arises.

Keywords: pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, cell of origin, KrasG12D

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is often characterized by local cancer spread and a high prevalence of metastases at presentation. One reason for the high mortality rate is the late diagnosis because of the inability to detect the cancer at early stages (1). Despite the characterization of several genetic abnormalities in PDAC, the initiating events as well as the cell of origin that gives rise to PDAC have remained elusive. It is recognized, however, that activating mutations of the Kras oncogene are the most frequent (≈90%) and the earliest genetic alterations associated with PDAC (2). Moreover, endogenous expression of a constitutively activated Kras (KrasG12D) allele in the whole pancreas from its earliest stages of development through the use of Pdx1- or Ptf1a-driven Cre recombinase strategy (Pdx1-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D or Ptf1a-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D mouse models) can induce preinvasive lesions or PanINs, for pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (3, 4). Despite the early embryonic oncogenic activation of Kras, these mice do not develop clear lesions until adulthood (2–4 months old), and metastatic disease is rare and does not occur until late in life (7–8 months) (3). Because this genetic approach leads to the targeting of mutated Kras to the whole pancreas, it does not allow for the definition of the specific cell type or cell of origin that would be particularly responsive to Kras oncogenic mutation. Conversely, mice displaying ectopic expression of oncogenic Kras in differentiated pancreatic cells (acinar or ductal) exhibit varying degrees and types of pancreatic lesions, but they do not progress through histologically defined PanINs and fail to recapitulate human PDAC progression (5). These data suggest that a more restricted population of progenitor cells could constitute the cell type responsive to Kras oncogenic activation.

We have now generated an animal model in which the endogenous KrasG12D is specifically activated in the Nestin-expressing cells, a population of exocrine pancreas progenitor cells. KrasG12D is subsequently activated in a more restricted population, the Nestin cell lineage. We now show that the Nestin-driven compound mutant mice develop mouse PanINs (mPanINs) in the same spatiotemporal manner as in a Pdx1-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D model where the Kras mutation is targeted to the whole pancreas.

Results and Discussion

Nestin Is a Marker of Exocrine Pancreas Progenitor Cells.

Nestin, a general protein marker of progenitor cells (6), is expressed during pancreas embryonic development (7, 8). Immunohistochemical studies indicate that Nestin is present in mesenchymal (9) and endothelial cells (10), whereas lineage-tracing experiments indicate that mostly exocrine cells are derived from Nestin-expressing progenitor cells (7, 8). In vivo, Nestin is not present in endocrine cells during either embryogenesis or adulthood, underscoring the conclusion that endocrine cells do not derive from Nestin-expressing progenitors (7, 8, 11–15). Moreover, in rodents, Nestin-expressing cells contribute to the regenerative capacity of the exocrine pancreas after partial pancreatectomy and during recovery from acute pancreatitis (15, 16).

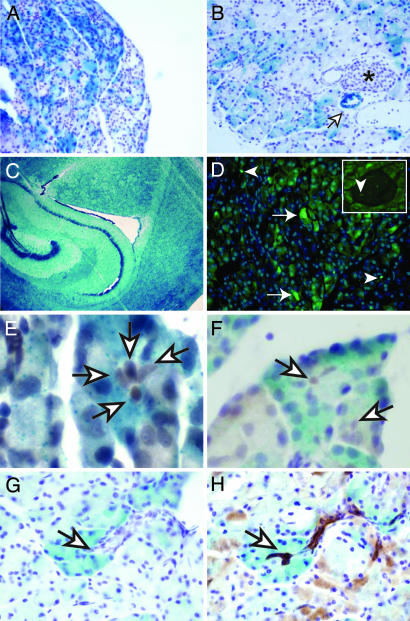

To confirm the role of Nestin as a marker of exocrine progenitor cells, we carried out lineage-tracing experiments by breeding mice that express the Cre recombinase under the control of Nestin promoter and enhancer-regulatory elements (17) with the Rosa26 (R26R) mouse line (18). This second mouse line carries a conditional β-galactosidase (LacZ) allele under the control of a transcription silencing region (Lox-Stop-Lox or LSL). Briefly, in double-transgenic mice Nestin-Cre/R26R, the cells that express transiently (or permanently) Nestin will also express the Cre recombinase. This enzyme will mediate the excision by homologous recombination of the LSL region and indirectly activate the expression of LacZ. Because this activation is an irreversible genetic event, all cells derived from Nestin-expressing progenitors will maintain LacZ expression. In adult mice (3–4 months old), a very strong LacZ signal is observed in acinar cells and some rare ductal cells (Fig. 1 A and B and data not shown). Although the LacZ signal was much weaker in 10-day-old mice (data not shown), it was seen in 20–50% of the exocrine pancreas in both age groups, exhibiting a heterogeneous pattern within each pancreas and between pancreata. By contrast, LacZ staining in the brain of the double-transgenic mice was fully penetrant, as evidenced by a diffuse signal that was reproducibly intense within defined regions (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Nestin cell lineage characterization and Nestin expression in the pancreas. (A–C) LacZ staining showing Nestin cell lineage tracing in Nestin-Cre/R26R mice. (A and B) Three- to four-month-old pancreas. Strong but heterogeneous staining is seen the in the acinar cells in some pancreatic segments, whereas weaker staining is seen in other segments; endothelial cells within blood vessels exhibit LacZ staining (B, open arrows), indicating that these cells also derive from Nestin-expressing progenitor cells, in contrast to the endocrine cells, which are always devoid of LacZ staining (B, star). (C) Three-month-old brain. All of the cells express LacZ. (D) GFP expression in the pancreas of a 2-month-old Nestin-GFP mouse is observed in discrete acinar (arrows) and endothelial/mesenchymal cells (arrowheads) throughout the pancreatic parenchyma; some endothelial cells (F Inset) within the islets are GFP-positive, whereas the endocrine cells are always devoid of a GFP signal. (E and F) Hes-1 immunolabeling on 3-month-old Nestin-Cre/R26R LacZ-stained pancreas. Note that the Hes-1-labeled cells (light brown, open arrows) are surrounded by a white ring, showing that they are not LacZ-stained. (G and H) Serial sections of a LacZ-stained acinus and its associated unstained ductule (open arrows), with (H) D. biflorus agglutinin staining revealing that the lectin binds to the duct cells and the centroacinar cells that are clearly devoid of LacZ staining. (Magnification: A, ×200; B, ×400; C, ×50; D, ×400; D Inset, ×200; E–H, ×600.)

The Nestin-Cre transgenic strain of mice (17) that we used, where Cre is under the control of both the promoter and enhancer of the Nestin gene, has been characterized for Cre expression in both the pancreas and the central nervous system (7, 17). When bred to the R26R strain, this mouse displayed LacZ expression at slightly reduced levels compared with Nestin expression in the early stages of pancreas development (7). The authors of the study proposed that there could be a short delay between Cre expression (under Nestin-regulatory regions) and the activation of LacZ. Subsequently, some early Nestin-expressing populations might not express LacZ. Another possible explanation for the limited pancreatic staining could be that the Nestin-Cre transgene has a mosaic expression in the pancreas, as was observed in the Pdx1-Cre mice used for the generation of the original Pdx1-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D animal model (3).

LacZ expression was also observed in some endothelial cells as shown by the staining of some blood vessels and in some mesenchymal cells (Fig. 1C and data not shown), as described previously (7). A few endothelial (PECAM-1-expressing) cells within the islets also exhibited LacZ staining (data not shown). However, LacZ staining was absent in the endocrine cells, confirming the hypothesis (7) that the Nestin-expressing cells are exclusively progenitors of the exocrine pancreas (both acini and ducts).

To demonstrate the presence of Nestin-expressing progenitor cells in the adult pancreas, we used a transgenic mouse line that expresses green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the control of the same Nestin-regulatory elements (19). A small population of GFP-positive cells was present in the acini in the adult pancreas (Fig. 1D). By contrast, GFP was not present in the endocrine cells, ducts, or blood vessels but was evident in some discrete PECAM-1-expressing cells in the islets (Fig. 1D Inset and data not shown).

Centroacinar cells have been proposed to be the progenitors in adult pancreas (20). To assess the possibility that the Nestin-expressing cells are centroacinar cells, we next performed immunofluorescence studies to look for the colocalization of Hes-1, a known centroacinar cell marker (20), with the GFP-expressing cells. Using three different Hes-1 antibodies, we did not detect any Hes-1 signal in the GFP-expressing cells (data not shown), indicating that the adult Nestin-expressing cells are not centroacinar cells. However, this experiment did not rule out the possibility that centroacinar cells could be derived from embryonic Nestin progenitors that no longer expressed Nestin. Therefore, we next examined the centroacinar cells in LacZ-stained Nestin-Cre/R26R adult pancreas. As shown in (Fig. 1 E–H), the centroacinar cells characterized by Hes-1 expression (Fig. 1 E and F) or Dolichos biflorus agglutinin binding (20) (Fig. 1 G and H) did not express LacZ, demonstrating that centroacinar cells are not derived from the Nestin progenitors. This experiment allowed us to rule out the possibility that in our following model, centroacinar cells could be the target of transformation events. Inasmuch as Nestin is up-regulated when acinar cell proliferation is induced in the pancreas (15, 16) and is expressed in multiple cultured human pancreatic cancer cell lines (present work; data not shown), one could propose that Nestin expression is activated or up-regulated in the pancreas during transformation. Our following in vivo data strongly suggest that the initial oncogenic event occurs in Nestin-expressing cells.

Endogenous KrasG12D Expression in the Pancreatic Nestin Cell Lineage Induces Intraepithelial Neoplasia.

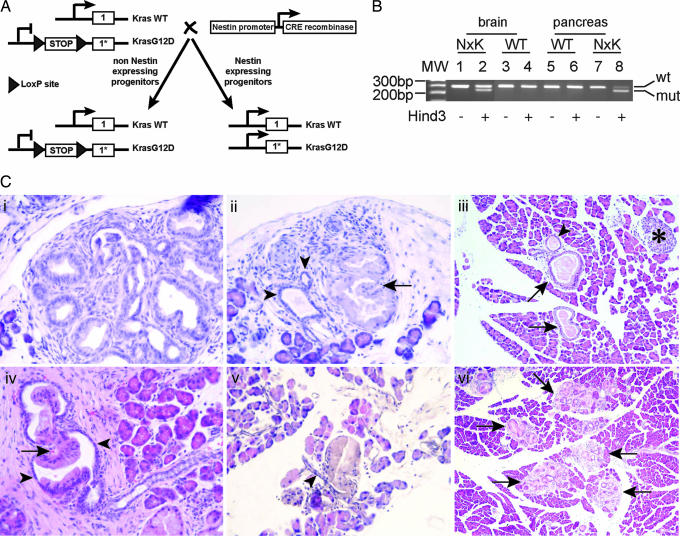

To generate a compound mutant mouse that expresses endogenous KrasG12D in the Nestin cell lineage, we have bred the mouse line carrying conditionally expressed mutated KrasG12D allele (3) with the transgenic Nestin-Cre mouse line (described above). The conditional activation of KrasG12D depends on the excision by homologous recombination of an LSL or transcription-silencing region situated upstream from the transcription initiation site. The conditionally activated Kras has been recombined into its own locus (knockin) (Fig. 2A). Thus, as is the case in human cancers, activated KrasG12D remains under the control of its natural promoter, eliminating any concerns that may arise from ectopic Kras overexpression, such as induction of cell cycle arrest and senescence (21). The KrasG12D mutation, commonly found in human PDAC, results in a glycine to aspartate substitution in the expressed protein, which compromises both its intrinsic and extrinsic GTPase activities. Expression of the KrasG12D allele results in constitutive downstream signaling of Ras effector pathways. Before breeding with the Nestin-Cre animals, the LSL-KrasG12D mice carry a functionally null allele of Kras and are maintained as heterozygous for the wild-type allele. Homozygosity for the LSL-KrasG12D allele would be equivalent to Kras complete knockout, which is embryonic-lethal (22). Breeding of the LSL-KrasG12D mice with the Nestin-Cre line generated animals with a heterozygous condition (Kras+/G12D) in the Nestin cell lineage (Fig. 2A). The expression of both alleles was analyzed by RT-PCR/ restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) in compound mutant tissues knowing that the KrasG12D allele carries a HindIII restriction site that allows for the discrimination between wild-type (WT) and KrasG12D messages (4). Similar levels of KrasG12D and WT Kras were detected in the brain of the compound mutant animals, whereas no mutant message was observed in the brain of WT siblings (Fig. 2B). In the compound mutant pancreas, the predominant message was KrasG12D message, whereas only WT Kras was detected in WT pancreas (Fig. 2B). Because we used a nonquantitative PCR approach, we cannot draw any conclusions as to the relative amounts of each message in the different tissues, but these data confirm that KrasG12D is activated in the compound mutant pancreas.

Fig. 2.

Conditional activation of Kras in the Nestin cell lineage is sufficient for generating mPanINs. (A) Breeding strategy of LSL-KrasG12D mice with Nestin-Cre mice. The Cre recombinase expressed under the control of Nestin-regulatory elements will mediate the recombination/excision of the LSL specifically in the Nestin-expressing cells. Subsequently, Kras will be conditionally activated only in the Nestin cell lineage. (B) RT-PCR/RFLP was performed on a 4-month-old pancreas and brain to confirm KrasG12D expression based on a KrasG12D allele-specific HindIII site. PCR-amplified cDNA was undigested (−) or digested (+) with HindIII, generating the mutant amplicon that migrates as the lower band in relation to the wild-type product. Lanes 1 and 2 are Nestin-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D (KxN) brain cDNAs, lanes 3 and 4 are wild-type brain cDNAs, lanes 5 and 6 are wild-type pancreas cDNAs, and lanes 7 and 8 are KxN pancreas cDNAs. There are similar levels of wild-type and mutated Kras products in the brain, whereas there is a preponderance of the mutated allele in the pancreas in 5 of 5 mutant mice. (C) mPanINs in Nestin-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D compound mutant mice. (Ci and Cii) Two-month-old pancreas. (Ci) Focus of PanINs1-A. (Cii) Normal ducts (arrowheads) can be observed next to a PanIN1-B (12). (Ciii–Cvi) Four-month-old pancreas. (Ciii) Isolated PanINs (arrows) can be observed, but the acini and the islets (star) are not affected. (Civ and Cv) PanIN1-B, where the transition between normal (arrowheads) and abnormal ductal epithelium is clearly observed. (Cvi) multiple PanIN foci are observed. (Magnification: Ci, Cii, Civ, and Cv, ×400; Ciii and Cvi, ×200.)

All of the compound mutant mice Nestin-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D developed pancreatic neoplasia (mPanINs) with close to 100% penetrance (1 mouse of 14 did not present pancreatic lesions). In 2-month-old animals, PanIN 1-A were observed, characterized by transition from normal cuboidal morphology to a columnar phenotype, nuclear crowding (Fig. 2Ci) and in some cases abundant supranuclear, mucin-containing cytoplasm (Fig. 2Cii). However, the polarity of the cells was maintained with basally located nuclei, and nuclear atypia, when seen at all, was minimal. Rare mPanIN 1-B characterized by papillary or micropapillary ductal lesions without significant loss of polarity or nuclear atypia were also observed. mPanIN 1-B were more abundant by 4 months (Fig. 2Civ). Although there were usually two to four qmPanINs foci per section, occasionally multiple foci were present (Fig. 2Cvi). Overall, the structure of the pancreas in the Nestin-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D mice appeared normal (Fig. 2Ciii). As observed in human pancreatic cancer, (i) all lesions present at 2 months appeared to have a clear ductal origin (no acinar–ductal metaplasia observed at this stage); (ii) strong inflammatory reactions surrounded many of the mPanINs; and (iii) the development of these lesions was restricted to the periphery of the pancreas, and only smaller ducts were affected, whereas larger ducts appeared normal. In 6-month-old mice, the mutant pancreata contained multiple ductal lesions, but there was no clear progression to more aggressive lesions.

Conditional Activation of KrasG12D in the Nestin Cell Lineage Versus the Whole Pancreas Generates a Similar Phenotype.

To determine whether the pancreatic Nestin cell lineage is the cell lineage responsive to KrasG12D activation, we have also generated Pdx1-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D compound mutant mice where oncogenic Kras activation is initially targeted to early pancreatic progenitors and subsequently to the whole pancreas. The Pdx1-Cre mouse line used for this work displays full pancreas expression (23, 24), and the compound mutant mice generated by breeding these Pdx1-Cre mice with the LSL-KrasG12D mice are thus similar to the Ptf1a-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D mice (3). We conducted a parallel analysis of both models. A blind histological analysis at 4 months in four mutant mice of each genotype demonstrated that it was not possible to discriminate between the two models. mPanINs appeared in similar number and type, and limited acinar–ductal metaplasia was observed in both cases. The epithelial nature of the lesions was confirmed by CK19 staining (Fig. 3A) and was consistent with what was described in human PanINs, with a robust accumulation of mucus in the lesions as evidenced by intense alcian blue staining (Fig. 3B) and the presence of the mucin-specific protein MUC-5 (Fig. 3C). In addition, there was increased labeling of the proliferation marker Ki67 in the PanINs and the surrounding inflammatory cells (Fig. 3D) and high expression levels of Gli3 and Smoothened (Fig. 3F and data not shown), respectively, a downstream target and a receptor of hedgehog (25).

Fig. 3.

Characterization of PanINs in 4-month-old Nestin-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D pancreas. (A) CK19 staining confirms the epithelial origin of the PanINs. (B) Alcian blue staining reveals the abundant mucin content of the lesions as confirmed by strong Muc5a immunoreactivity (C), a high level of Ki67 observed in PanIN 1-A and surrounding inflammatory cells (arrowheads) but no staining observed in adjacent normal acini (D), Cox2 expression limited to the abnormal areas of the ductal epithelium (arrows) (E), but Gli3 (F) staining the nuclei of all of the cells in the PanINs as well as in the adjacent inflammatory (solid arrowheads) and some acinar (open arrowheads) cells. (Magnification: ×400.)

It is interesting to note that the hedgehog signaling pathway was also activated in the acinar and inflammatory cells adjacent to the lesions (Fig. 3F), whereas no labeling is observed in normal pancreas. By contrast, Cox2 staining was confined to the histologically abnormal cells within the PanINs (Fig. 3E). Although Kras is classically known for activating the Raf/ERK, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, and Ral pathways, Cox2 is also known to be up-regulated by oncogenic Kras and to contribute to cancer initiation and progression while promoting angiogenesis and inflammation (26–28). The highly restricted expression of Cox2 in the neoplastic part of the ducts at very early stages of lesion formation suggests that it may be a major downstream mediator of oncogenic Kras with respect to PanIN initiation.

Our data thus confirm that Nestin-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D mice develop pancreatic lesions that exhibit the histological features of early human PanINs, that the Nestin cell lineage in the pancreas is the candidate cellular compartment for the development of pancreatic neoplasia, and that this mouse model could prove useful in testing various chemopreventive strategies targeted at PanIN lesions.

Reduced Acinar–Ductal Metaplasia at 6 Months in Nestin-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D Versus Pdx1-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D Pancreata.

By 6 months of age, only mPanINs 1-A and B were detected in the pancreas of both mouse models. However, the pancreas in the Pdx1-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D mice exhibited extensive acinar–ductal metaplasia, a phenomenon that has also now been observed in another laboratory using the Pdx1-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D model (S. F. Konieczny, personal communication). By contrast, there was little or no metaplasia in the Nestin-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D pancreas (Fig. 4A), as demonstrated by blind scoring of sections of four Nestin-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D and four Pdx1-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D pancreata. Although the pancreata in the Nestin-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D model were smaller than in the Pdx1-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D model, the same blinded analysis revealed that Nestin-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D mice harbored more free-standing PanINs. It is known that when KrasG12D is targeted to differentiated pancreatic cells, prominent acinar–ductal metaplasia is observed, with subsequent development of acinar cell carcinomas (5). One possible explanation for the extensive acinar–ductal metaplasia observed in the Pdx1-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D pancreas could be that oncogenic Kras is activated in a higher number of differentiated cells. By contrast, the limited acinar–ductal metaplasia in the Nestin-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D model may be a reflection of the more restricted targeting of the oncogene.

Fig. 4.

KrasG12D targeting to the Nestin cell lineage generates a more specific model for PanINs formation. (A) Less acinar–ductal metaplasia observed at 6 months in the pancreas of Nestin-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D mutants as shown by comparison of CK19 staining between Nestin-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D (A1) and Pdx1-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D (A2) pancreas. Note the abundance of acinar-like structures that stain for CK19 in the Pdx1-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D pancreas, next to normal ducts (arrowhead). (B) Cell lineages determination model. During pancreas development, multiple progenitor populations with progressively more restricted differentiation potential are generated. We propose that the progenitor population characterized by Nestin expression (in gray) specifically gives rise to exocrine pancreas; that in the adult pancreas, the Nestin-expressing cells function as adult progenitor cells; and that this cell population could be the cell of origin for PDAC.

We did not observe formation of advanced PanINs or invasive cancer at 6 months in either model. Because all cells of the central nervous system are derived from Nestin-expressing progenitors, the Nestin-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D mice have massive activation of KrasG12D in their central nervous system, and their survival drops dramatically after 6 months, most likely because of multiple neurological problems.

Conclusion

Our data demonstrate that activation of oncogenic Kras in the Nestin cell lineage is sufficient for the initiation of premalignant PanIN lesions in the pancreas. The formation of lesions occurs initially with the same frequency as that observed when mutated Kras is targeted to the whole pancreas. As in a Pdx1-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D model, the lesions form only in adult animals. These observations suggest that the initial oncogenic lesion in the pancreas could occur in a cell type that maintains proliferative properties and has the capacity to acquire additional mutations, potentially a progenitor cell. Pancreatic embryonic Nestin-expressing progenitors give rise to part of the exocrine pancreas, but targeting of oncogenic Kras to differentiated acinar or ductal does not generate PanIN-like lesions, indicating that there may be an undifferentiated Nestin-expressing cell population that would be sensitive/responsive to Kras oncogenic activation. The facts that there are Nestin-expressing cells in the adult pancreas and that this population can transiently expand when proliferation is induced in the pancreas strongly suggest that these cells could be adult progenitors. By contrast, our data demonstrate that centroacinar cells are not derived from Nestin-expressing cells, ruling out the possibility that centroacinar cells give rise to PanINs in our model. We propose that the adult Nestin-expressing cells are the cells of origin for PDAC (Fig. 4B). An extensive characterization of these cells as well as the targeting of oncogenic Kras to the adult Nestin-expressing cell compartment will give a definitive answer.

Materials and Methods

Mouse Colony Generation.

The LSL-KrasG12D (01XJ6-B6;129-Kras2tm4Tyj) mice were obtained from the Mouse Models of Human Cancers Consortium (National Cancer Institute, Frederick, MD). The R26R mice [B6.129S4-Gt(ROSA)26SortmSor/J] and the Nestin-Cre mice [B6.Cg-Tg(Nes-cre)1Kln/J] were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). The Pdx1-Cre mice were kindly provided by G. Gu (23). The Nestin-GFP mice were a generous gift from Gregori Enikolopov (29). All genotyping was done by PCR following the conditions of the providers.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry.

Nestin-Cre/LSL-KrasG12D and Pdx1-Cre/ LSL-KrasG12D mice were perfused with PBS then 10% (wt/vol) formalin. The tissues were dissected, fixed overnight, and embedded in paraffin. Nestin-Cre/R26R and Nestin-GFP tissues were briefly fixed in 10% formalin, cryopreserved in PBS/30% (wt/vol) sucrose, and cryoembedded in OCT compound. For immunostaining, if required, antigen-unmasking solution (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. The proteinase K procedure was used for CK19 staining. Immunostaining procedures were as described in ref. 4. The antibodies and dilution used were TromaIII (CK19 antibody developed by Rolf Kemler and obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA), 1:10; Muc5a (Novocastra, Newcastle upon Tyne, U.K.), 1:30; Ki67 (Novocastra), 1:200; Gli3 and Smo (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), 1:50; Hes1 (Chemicon, Temecula, CA; T. Sudo, Toray Industries, Inc.; N. Brown, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center; all used at respective dilutions of 1:200, 1:500, and 1:400). Alcian blue and LacZ staining were done as described in ref. 7 and www.ihcworld.com. RT-PCR/RFLP was done as described previously (4). D. biflorus agglutinin (Vector Laboratories) staining was done as described in ref. 20.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. C. Wright and G. Gu (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN) for Pdx1-Cre mice, Dr. G. Enikolopov (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY) for Nestin-GFP mice, Drs. T. Sudo (Toray Industries, Inc., Kamakura, Japan) and N. Brown (Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH) for Hes-1 antibodies, and Allison Young for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health Grants CA-75059 and CA-102687 (to M.K.).

Abbreviations

- LSL

Lox-Stop-Lox

- PanINs

pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia

- PDAC

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- R26R

Rosa26

- RFLP

restriction fragment length polymorphism.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.DiMagno EP, Reber HA, Tempero MA. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1464–1484. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70298-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klimstra DS, Longnecker DS. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:1547–1550. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hingorani SR, Petricoin EF, Maitra A, Rajapakse V, King C, Jacobetz MA, Ross S, Conrads TP, Veenstra TD, Hitt BA, et al. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:437–450. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aguirre AJ, Bardeesy N, Sinha M, Lopez L, Tuveson DA, Horner J, Redston MS, DePinho RA. Genes Dev. 2003;17:3112–3126. doi: 10.1101/gad.1158703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hruban RH, Adsay NV, Albores-Saavedra J, Anver MR, Biankin AV, Boivin GP, Furth EE, Furukawa T, Klein A, Klimstra DS, et al. Cancer Res. 2006;66:95–106. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lendahl U, Zimmerman LB, McKay RD. Cell. 1990;60:585–595. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90662-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delacour A, Nepote V, Trumpp A, Herrera PL. Mech Dev. 2004;121:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esni F, Stoffers DA, Takeuchi T, Leach SD. Mech Dev. 2004;121:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selander L, Edlund H. Mech Dev. 2002;113:189–192. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Treutelaar MK, Skidmore JM, Dias-Leme CL, Hara M, Zhang L, Simeone D, Martin DM, Burant CF. Diabetes. 2003;52:2503–2512. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.10.2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein T, Ling Z, Heimberg H, Madsen OD, Heller RS, Serup P. J Histochem Cytochem. 2003;51:697–706. doi: 10.1177/002215540305100601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernardo AS, Barrow J, Hay CW, McCreath K, Kind AJ, Schnieke AE, Colman A, Hart AW, Docherty K. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;253:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ueno H, Yamada Y, Watanabe R, Mukai E, Hosokawa M, Takahashi A, Hamasaki A, Fujiwara H, Toyokuni S, Yamaguchi M, et al. Pancreas. 2005;31:126–131. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000172564.80921.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taguchi M, Otsuki M. J Mol Histol. 2004;35:785–789. doi: 10.1007/s10735-004-0948-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim SY, Lee SH, Kim BM, Kim EH, Min BH, Bendayan M, Park IS. Dev Dyn. 2004;230:1–11. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishiwata T, Kudo M, Onda M, Fujii T, Teduka K, Suzuki T, Korc M, Naito Z. Pancreas. 2006;32:360–368. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000220860.01120.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tronche F, Kellendonk C, Kretz O, Gass P, Anlag K, Orban PC, Bock R, Klein R, Schutz G. Nat Genet. 1999;23:99–103. doi: 10.1038/12703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soriano P. Nat Genet. 1999;21:70–71. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mignone JL, Kukekov V, Chiang AS, Steindler D, Enikolopov G. J Comp Neurol. 2004;469:311–324. doi: 10.1002/cne.10964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stanger BZ, Stiles B, Lauwers GY, Bardeesy N, Mendoza M, Wang Y, Greenwood A, Cheng KH, McLaughlin M, Brown D, et al. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serrano M, Lin AW, McCurrach ME, Beach D, Lowe SW. Cell. 1997;88:593–602. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81902-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson L, Greenbaum D, Cichowski K, Mercer K, Murphy E, Schmitt E, Bronson RT, Umanoff H, Edelmann W, Kucherlapati R, Jacks T. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2468–2481. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.19.2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gu G, Brown JR, Melton DA. Mech Dev. 2003;120:35–43. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00330-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heiser PW, Lau J, Taketo MM, Herrera PL, Hebrok M. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2006;133:2023–2032. doi: 10.1242/dev.02366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Osterlund T, Kogerman P. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:176–180. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maitra A, Ashfaq R, Gunn CR, Rahman A, Yeo CJ, Sohn TA, Cameron JL, Hruban RH, Wilentz RE. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;118:194–201. doi: 10.1309/TPG4-CK1C-9V8V-8AWC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tucker ON, Dannenberg AJ, Yang EK, Zhang F, Teng L, Daly JM, Soslow RA, Masferrer JL, Woerner BM, Koki AT, Fahey TJ., III Cancer Res. 1999;59:987–990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dannenberg AJ, Subbaramaiah K. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:431–436. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00310-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buchholz F, Refaeli Y, Trumpp A, Bishop JM. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:133–139. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]