Abstract

Typological approaches have become highly influential in research on violence in couples, and yet issues related to such approaches have not been well addressed. We review the utility of batterer typologies, both for clinical applications and for understanding violence in couples. The principal types of batterer typologies are discussed, along with a number of issues that might limit their utility for explaining the etiology and developmental course of partner violence in couples. We propose a dyadic model of couples’ aggression, and we explain ways that such a model provides better conceptualization of the development of the couples’ violence over time, including issues of persistence and desistance of violence, and that can help inform prevention and treatment.

Keywords: Batterer typology, Clinical implications, Partner violence, Developmental systems perspective

Typological Approaches to Violence in Couples: A Critique and Alternative Conceptual Approach

After over a decade of jousting between family conflict and feminist theorists regarding violence in couples (Gelles & Loseke, 1993), batterer and violence typological approaches entered the arena. This body of work has included typologies of batterers that generally identify among two and four subtypes on the basis of psychopathology and engagement in partner violence of predominantly male (e.g., Holtzworth-Munroe, Meehan, Herron, Rehman, & Stuart, 2000; Holtzworth-Munroe & Stuart, 1994; Tweed & Dutton, 1998), and occasionally of female (Babcock, Miller, & Siard, 2003; Swan & Snow, 2002), perpetrators. Some typologies are based on physiological responses of men during problem-solving discussions with their partners (Gottman et al., 1995), and other typologies have focused more on the motivation for the violence (Chase, O’Leary, & Heyman, 2001; Johnson, 1995).

Typological approaches have become highly influential in research on violence in couples. So much so, in fact, that in their review of a decade of research in the area of couples violence, Johnson and Ferraro (2000) focused almost exclusively on defining typologies of violence and batterers. Chase et al. (2001) even argued, “The development and testing of typologies is the zeitgeist in partner-violence research” (p. 567). In a recent review of the utility of offender typologies, Cavanaugh and Gelles (2005) also argue that batterer typologies have allowed room for alternative explanations for why some men are violent toward women, and it is from these typologies--which help explain heterogeneity--that more effective treatment strategies can be developed. They assert that “One of the questions to be examined is not only what kind of batterer program works, but what works, for which types of men, and under what circumstances” (p. 157). Others also interpret the typologies as the basis for differential treatment approaches (Greene & Bogo, 2002; Stith, Rosen, McCollum, & Thomsen, 2004).

A major contribution of batterer typologies is that they have provided significant insights on the heterogeneous nature of partner violence and have pointed to the importance of personality and psychopathological characteristics, both in understanding partner violence and for the treatment of violent individuals. Moreover, it has been suggested that typologies will also help identify different etiological mechanisms of partner violence (Gottman et al., 1995; Holtzworth-Munroe & Stuart, 1994). Therefore, it seems only natural that the typology approach has drawn a great deal of attention from researchers in the area, particularly from clinicians. Whereas a number of studies have sought to identify different types of batterers with a variety of samples, we posit that the conceptual and clinical implications and advantages of typological approaches have yet to be well specified and tested. We believe that it is of particular concern that careful consideration be given to definitions of subtypes of batterers and how meaningfully different in type they are, whether different types have any substantive predictability over severity of violence more generally, and the validity of the typologies (i.e., replicability).

In this article, we consider the conceptual and clinical utility of batterer typologies. First, summary findings regarding the principal types of batterer typologies are outlined briefly, along with issues that limit their utility for explaining the etiology of domestic violence in couples and for describing the course of such aggression over time. It is not within the scope of this article to conduct a full review of all batterer typologies. Rather, we discuss some of the major and most influential typologies in the field. For such reviews, the reader is referred to Cavanaugh and Gelles (2005), Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart (1994), and Holtzworth-Munroe, Meehan, Herron, Rehman, and Stuart (2003). Second, we outline a dyadic model of couples aggression and the ways that such a model may be more helpful in conceptualizing the development of the behavior over time, including issues of persistence and desistance. The dyadic model also supports an approach to treatment that centers on the dyad for some, although not all, couples. The model has broader applications to violent interactions more generally, and thus is consistent with the recent call for greater integration of theory and research across areas within family violence research (Slep & O’Leary, 2001; Tolan, Gorman-Smith, & Henry, 2006). Finally, we discuss the clinical utility of batterer typologies. We summarize a few studies that evidenced limited clinical implications of current batterer typologies and address issues that need to be further considered by clinicians. Implications of the dyadic model for future research and clinical intervention are discussed.

Principal Batterer and Violence Typologies

On the basis of a thorough review of previous literature, Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart (1994) have suggested that men who are maritally violent show heterogeneity in individual characteristics and vary along three dimensions; severity and frequency of violence, generality of violence (confined to family or including nonfamily), and the man’s psychopathology. Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart identified three subtypes of male batterers; namely, generally violent/antisocial, dysphoric/borderline, and family only. In a later empirical test of this hypothesized typology (using cluster analysis of measures of husband violence toward a partner, general violence, antisociality, and fear of abandonment), four clusters were identified, including the three hypothesized groups and an additional low-level antisocial group who fell between the family only and generally violent and antisocial group (Holtzworth-Munroe et al., 2000). Several studies have generally found support for the three group batterer typology (Hamberger, Lohr, Bonge, & Tolin, 1996; Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Huss, & Ramsey, 2000; Tweed & Dutton, 1998; Waltz, Babcock, Jacobson, & Gottman, 2000), although the number and characteristics of all the subgroups are still debatable (Huss & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 2000). Holtzworth-Munroe at al. (2003) argued that they found some support for the stability of the subtypes, but the evidence of such continuity is weak as indicated by the significant overlap of characteristics between generally violent and borderline/dysphoric men (Sartin, 2005). Lack of distinction between the generally violent and borderline/dysphoric types was also found in a study by Delsol, Margolin, and John (2003) who conducted latent class analyses for a community sample of men who used any violence. They identified three groups, namely family only, medium violence, and generally violent/psychologically distressed. They did not find separate groupings of borderline/dysphoric and generally violent/antisocial types.

There has been some work examining typologies of aggression in women. Babcock et al. (2003) used the Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart (1994) typology and examined violence among 52 women referred for treatment. They identified two groups: generally violent and partner only. Swan and Snow (2002) interviewed women and asked them about both their and their partner’s aggression. They identified three types of relationships: women as victims (34%), women as aggressors (12%), and mixed relationships (50%). These findings indicate heterogeneity in characteristics of women involved in domestic violence.

In another influential batterer typology, on the basis of physiological reactivity during marital conflict, Gottman et al. (1995) identified two subtypes of men. Type 1 men were more violent toward others outside of the relationship (e.g., coworkers), showed higher levels of antisocial behavior and sadistic aggression and decreases in arousal during conflict with their wife. Type 2 men were more dependent, needy, emotionally volatile, and tended to show increases in arousal during conflict with their wife. Apart from the family only group, these typologies seem to converge in identifying a group of men who are high in general antisocial behavior and a group who may still be elevated in antisocial behavior to some degree, but also show depressive/anxious and borderline personalities. However, at least two studies have failed to replicate the Gottman et al. typology (Babcock, Green, Webb, & Graham, 2004; Meehan, Holtzworth-Munroe, & Herron, 2001), and there have been no consistent replications.

A further typological approach based more explicitly on the motivation for the violence than on characteristics of the perpetrator is exemplified by the influential work of Johnson and colleagues (Johnson, 1995; Leone, Johnson, Cohan, & Lloyd, 2004). He attempted to explain the discrepant findings from gender feminist and family violence research by positing two theoretically different kinds of violence in couples; namely, common couple violence and patriarchal terrorism, later changing the latter term to “intimate terrorism.” Johnson (1995) argues, with good justification, that feminist studies of agency samples and family violence studies have been on samples showing almost no overlap in levels of physical aggression. According to Johnson (1995), common couple violence is generally found in the larger scale surveys. He hypothesizes that this involves conflicts between partners that are poorly managed, occasionally escalate to minor violence, and more rarely to serious violence. Such violence is more likely to be mutual, of lower frequency, and less likely to persist. On the other hand, he argues that intimate terrorism usually involves patterned violence with the purpose of maintaining domination, is typically found in agency samples, and that such violence is likely to be much more frequent, persistent, and almost exclusively to be perpetrated by men. In a recent evaluation of violence research, Jasinski (2005) considered that Johnson’s theory (and 1995 article) resolved the longstanding argument between gender feminist and family conflict researchers regarding partner violence by men and women.

There has been some support for the Johnson hypothesis, as groups selected as likely to show higher severity of violence (e.g., batterer treatment or shelter samples) do show more severe violence and control behaviors than groups selected as likely to be less severe (e.g., neighborhood or student samples). However, the groups were selected as showing very different severities of violence and included extreme groups by design (Frieze & Brown, 1989; Graham-Kevan & Archer, 2003). Other tests have involved dichotomizing continuous scales of men’s violence but not assessing women’s violence, even though the theory pertains to mutual versus one-sided violence (Johnson & Leone, 2005); thus, the degree of mutuality versus one-sidedness of the violence could not be assessed. There is some evidence of mutuality of violence for shelter samples. McDonald, Jouriles, Tart, and Minze (2006) conducted a study of children’s adjustment in families with severe violence by male partners toward the mother. They recruited a sample from domestic violence shelters, where the mother had to have experienced at least one act of partner-to-mother physical violence in the past year. Over the same time period, it was found that 96% of the men and 67% of the women (according to only the women’s reports) had engaged in severe violence toward a partner. Thus, violence was mutual in the majority of cases. The interesting and important question of whether two groups versus a continuum would emerge from a population-based sample has not been tested. Further, as summarized by Tolan et al. (2006), couples with unidirectional violence actually report fewer acts and forms of violence than do bidirectional violent couples, and the acts are less likely to lead to injuries and further violence. Therefore, two key aspects of the Johnson hypothesis have yet to be established. First, that the motivations behind the violence are significantly different for more severe versus less severe violence, and second that more severe violence is one sided rather than mutual.

Rethinking Conceptual Approaches to Understanding the Etiology and Course of Violence

In this section, we discuss a number of issues that need further consideration within the field. These issues include the extent to which the identified typologies may be on the basis of differences of degree more than type; conceptualization of change in aggression; difficulties with the distinction between instrumental and expressive motivations for violence; and the primary focus on individual characteristics rather than dyadic context and interaction processes.

Differences of type versus degree

A key issue for batterer typologies is whether they reliably identify groups that do differ qualitatively rather than quantitatively. Cavanaugh and Gelles (2005) summarize findings from batterer typology studies, including Gondolf (1988), Gottman et al. (1995), Hamberger et al. (1996), Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart (1994), and Johnson (1995). They conclude that three types of batterers are common across current typology research--a low, moderate, and high-risk offender. These three types are respectively low, moderate, and high on severity and frequency of violence and on psychopathology, as well as criminal history. White and Gondolf (2000) also argued that six subgroups of batterers they identified on the basis of individual Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory (MCMI) profiles reflect, in fact, a continuum of narcissistic and avoidant tendencies that cut across the subgroups. The batterers could be characterized as ranging from modest personality dysfunction to personality pathology. Therefore, the different types of batterers seem to be ordered essentially along a few dimensions of violence and individual psychopathology, and this does not appear to be enough evidence for qualitatively different subtypes of batterers. The case for typological approaches would be more convincing if different types of batterers showed more distinctive patterns of associations among related factors.

Typological approaches and change in violent behavior

A second key issue regards the extent to which the conceptual models underlying the typologies are adequate to describe violence in couples. In current typologies in the area of domestic violence, individuals are grouped into categories on the basis of their behavior at one point in time. Cavanaugh and Gelles (2005) argue that “Because there are particular characteristics specific to each type that establishes thresholds distinct to each classification, it is unlikely that an offender will move from one particular type to another” (p. 162). However, there seems little empirical evidence to support this expectation. This conceptual approach is not compatible with recent findings from various developmental studies. Some typology theories speak to aspects of change. For example, Holtzworth-Munroe et al. (2003) found that family-only violent men were more likely to desist from violence over time than were men in other groups. However, questions regarding how much an individual’s or a couples’ behavior has changed and why, and distinctions between those who have chronic problems over time and those who have transitory problems, are hard to conceptualize and address with a model that categorizes individuals at one point in time.

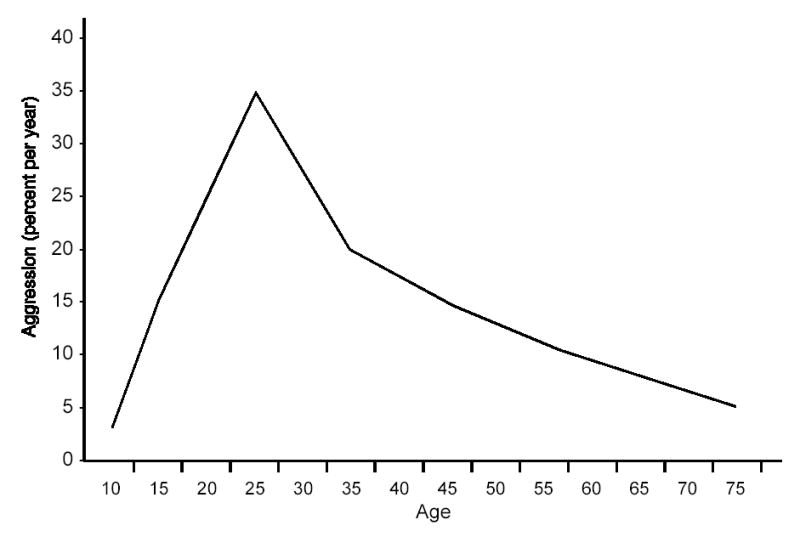

A number of studies have indicated substantial changes over time both in levels of violence and in the occurrence of any such aggression toward a partner. Samples ranging from cohabiting or newlywed young adults (Aldarondo, 1996; Mihalic, Elliott, & Menard, 1994; O’Leary et al., 1989) to the National Family Violence Survey, which includes a wide age range (Feld & Straus, 1989), have been consistent in finding desistance rates of around 50% for men over a 1-year period. Rates of physical aggression toward a partner have been found to be highest at young ages and to decrease with time (Gelles & Straus, 1988). Shown in Figure 1 (reproduced from O’Leary, 1999) are hypothesized age trends in prevalence in men’s physical aggression toward a partner. These estimates indicate a sharp rise from ages 15–25 years, a peak prevalence at around age 25 years, and a sharp decline to about age 35 years. Similarly, Rennison (2001) presented data regarding victimization of women by age from the National Crime Victimization Survey. In 1999, rates for partner violence experienced by women were about 15 to 16 (per 1000) women at ages 16–19 and 20–24 years, 9 at ages 25–34 years, 6 at ages 35–39 years, and 3 at ages 50 years or older. Thus, in the early 20s, the prevalence of violence toward women by their partners was close to three times higher than in the late 30s. These findings are not consistent with typology approaches that have the underlying assumption that relatively stable male individual differences are driving violence and, thus, that the subgroups themselves do not tend to change (Cavanaugh & Gelles, 2005).

Figure 1.

Hypothesized trends in male-to-female partner aggression by age.

A recent review of the literature of typology studies of maritally violent men (Holtzworth-Munroe et al., 2003) found only 1 study out of 24 that included any longitudinal data, and that study examined differences in relationship stability as an outcome of the subtypes (Gottman et al., 1995) rather than the stability of the typology. Holtzworth-Munroe et al. (2003) then assessed the characteristics of the sample on which they tested their typology (Holtzworth-Munroe et al., 2000) 1.5 (Time 2) and 3 years (Time 3) after the initial assessment. They did not reconduct cluster analyses to test stability of the classifications. However, they did examine mean levels of key behaviors of men across the original four groupings--generally violent antisocial (GVA), borderline-dysphoric (BD), low level antisocial (LLA), and family only (FO)--at the later points in time, including the typology criteria measures, associated hypothesized covariates, and relationship separations. Findings of the study are somewhat hard to interpret in that many couples separated and had little contact at the follow-up assessments. The findings did indicate some continuity of behavior over time. For example, the BD and GVA men had the highest levels of reported husband violence at follow up, and the GVA men were the least likely to desist from violence.

However, there were also several indications of substantial change over time in those who did have contact with their partners, including the behaviors that were the basis for the typology. First, the level of husband violence decreased over time for all groups; thus, the GVA group, originally hypothesized as likely to be chronic in violence, did in fact decrease in violence toward their wives. Second, the GVA group decreased in general violence levels (i.e., violence outside the home). Third, for both fear of abandonment and antisocial personality, the BD men were not distinguishable from the GVA men at Time 2 or Time 3. Thus, the findings indicated considerable change over time in the key behaviors of the men in the different groupings, such that the types were now less distinguishable. In particular, the GVA and BD groups were now hard to distinguish. In a study that presented some additional findings regarding the stability of the batterer typology categories, Holtzworth-Munroe and Meehan (2004) tested, on the basis of the men’s Time 2 and Time 3 scores, into which Time 1 subgroups the men would be placed. The percent agreement of groupings overall between Time 1 and Time 2 was 58% and with Time 3 was 54%. The FO men accounted for a large proportion of the stability, as they showed a stability of around 90%. However, this may be due to the fact that they continuously classified men as FO (the least severe classification) even when they had desisted, as very few escalated and overall the sample decreased in violence. Thus, if desistance were taken into account, the percent agreement would presumably be significantly lower.

Instrumental versus hostile aggression

A critical issue that may limit the utility of typological approaches is that some of them tend, either explicitly or implicitly, to rest on the assumption that more frequent physical aggression, when hypothesized to be one sided and by men in particular, is a distinctly different type of aggression; namely, instrumental or controlling, premeditated or emotionally cold, as compared with angry, impulsive, emotionally hot, or hostile aggression, which is hypothesized to occur more frequently during dyadic conflicts. The notion of instrumental aggression on the basis of gender issues underlies the Duluth Model of batterer treatment (Pence & Paymar, 1993). The instrumental versus hostile dichotomy is in line with Johnson’s intimate terrorism versus common couple violence distinction, and it also is related to other typologies hypothesizing groups involving one-sided aggression versus mutual conflict (e.g., Chase et al., 2001; Gottman et al., 1995). However, as Bushman and Anderson (2001) persuasively argue, the hostile versus instrumental aggression distinction has considerable problems in fitting human aggressive behavior (such as that even impulsive or hostile aggression is driven by more complex goals than simply trying to hurt someone), and continued attempts to theorize from this dichotomy will impede further advances in understanding and preventing or controlling aggression.

Bushman and Anderson (2001) contend that there are two major conceptual problems with the hostile-instrumental dichotomy. First, it is confounded with the automatic versus controlled information processing dichotomy, such that it requires hostile aggression to be automatic and instrumental aggression to be controlled. However, some aggression that is obviously hostile has controlled features, and some instrumental aggression has automatic features. The second problem is that it excludes aggressive acts on the basis of multiple motives, and it has difficulty accounting for three distinct motive-behavior relations; namely, the same motives can drive either type of aggression, different motives can drive the same aggressive behavior, and many aggressive behaviors are mixtures of hostile and instrumental aggression. They present a definition of aggression where the immediate or proximate goal is always intent to harm, and primary or superordinate goals differ. An act of aggressive behavior may be the result of two or more simultaneous primary goals. Such motivations as expressing disapproval of a comment or behavior and retaliation may play into the same incident of physical violence.

Evidence for the complexity of occasions of physical violence comes from an analysis of the descriptive police reports of domestic violence incidents. These reports include interviews with the victim and usually with the perpetrator, description of physical evidence of injury, and contextual factors (e.g., evidence of intoxication). Capaldi et al. (2006) found a considerable variation in the contextual factors surrounding these incidents, including use of substances, the stage of the relationship (e.g., in break-up phase), the levels of involvement of each partner in the aggression, and the reported motivations. This supports Bushman and Anderson’s (2001) contention that the hostile versus instrumental dichotomy of physically aggressive behavior is overly simplistic (see also Gendreau & Archer, 2005). It is our view that violence toward a partner involves various factors, including individuals’ characteristics and contextual and situational factors, and that the instrumental versus hostile violence dichotomy is not an adequate portrayal of violence in couples. Therefore, basing treatment decisions solely on it may hinder positive treatment outcomes.

Individual versus dyadic models

We posit that to advance understanding of partner violence, conceptual models that are more strongly focused on the characteristics of both members of the dyad and on interactional processes and aggression over time than are typological models, are needed. Other researchers have reached similar conclusions (Jouriles, McDonald, Norwood, & Ezell, 2001; Tolan et al., 2006). Whereas most typologies discuss dyadic factors as being relevant to at least one subtype (i.e., family only group, common couple violence), dyadic factors are not a strong focus.

Recent findings regarding stability and change in aggression in couples emphasizes the importance of a dyadic approach to understanding violence. In a longitudinal study of a community sample of young couples, Capaldi, Shortt, and Crosby (2003) found that there was significant stability in physical and psychological aggression toward a partner by both the young man and woman, if the couple remained intact from late adolescence to young adulthood. However, if the young man was with a new partner, there was no significant correlational association in physical or psychological aggression (as reported by the man and woman for each partner) across the period. This finding indicates that the men’s aggressive and violent behavior showed stability if he remained with the same partner over time, but changed substantially when they changed partners. This change was likely due to changes in interaction patterns across relationships. This could not be accounted for by a “honeymoon” effect at the start of the relationships with the new partners, because the prevalence of any physical aggression toward a partner of the men with new partners was 32%. Further evidence in support of a dyadic approach was found in that, for the couples who stayed together, the men’s violence toward a partner at age 20–23 years was just as well predicted by his partner’s prior physical aggression as by his own. In addition, change scores in violence for each partner over time were strongly associated, indicating that the partners tended to increase or decrease in violence together or in a synchronized fashion. This finding indicates that factors related to the partner--and dyad--are critical in relation to continuance of aggression and violence.

O’Leary and colleagues (O’Leary & Slep, 2003; Riggs & O’Leary, 1989, 1996) also present models of courtship or dating aggression where they examine the role of partner factors, particularly conflict and aggression. For a sample of high school students who remained in relationships for 3 months, O’Leary and Slep (2003) found that physical aggression against dating partners showed significant stability over time for both boys and girls, and in a path model including both partners’ behaviors, individual physical aggression was predictive of partner’s physical aggression 3 months later. Pan, Neidig, and O’Leary (1994) also reported that relationship discord was the most significant predictor of physical aggression toward a partner.

A Dynamic Developmental Systems Approach to Understanding Violence Toward a Partner

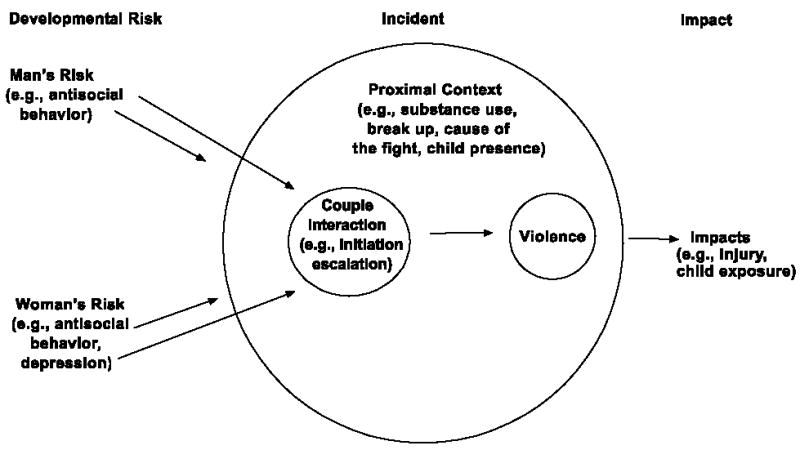

We have conceptualized behavior in couples as a dynamic developmental system in which behavior in the dyad is inherently interactive and also responsive to developmental characteristics of each of the partners and to both broader and more proximal contextual factors. We have built and tested aspects of such an early life-span model in a series of studies over the past decade, predominantly using the Oregon Youth Study sample. A summary of the model is depicted in Figure 2 and is described in more detail in Capaldi, Shortt, and Kim (2005). The model provides a framework that can aid in understanding developmental risk for violence toward a partner, the course of such aggression over time, and bidirectional influences on the behavior and course. The approach emphasizes the importance of considering first the characteristics of both partners as they enter and then move through the relationship, including personality, psychopathology, ongoing social influences (e.g., peer associations), and individual developmental stage. The second emphasis is on the risk context and contextual factors that affect aggression toward a partner. The third emphasis is on the nature of the relationship itself, primarily the interaction patterns within the dyad as they are initially established and as they change over time, as well as factors affecting the context of the relationship.

Figure 2.

Dynamic developmental systems model of partner violence.

Each of the areas in the model identifies important targets for investigation as to their role in violence and its impacts and for potentially malleable prevention and intervention points. Programs to reduce prior psychopathology may help prevent aggression toward a partner. Contextual factors also provide key information. If the couple is breaking up, then treatment could focus around counseling for negotiating such factors as child custody and property division. If the couple are staying together, then counseling for the couple on avoiding violence in the future is indicated, including strategies for nonviolent problem solving, avoiding escalation toward violence, and allowing your partner to take a time out (Capaldi et al., 2006). For some couples, drinking behavior is closely associated with domestic violence (e.g., Leonard, Bromet, Parkinson, Day, & Ryan, 1985; Pan et al., 1994). Therefore, substance use treatment may promote positive change, and there is evidence that interventions reducing alcohol use for male alcoholic patients are associated with reduced violence (O’Farrell, Murphy, Stephan, Fals-Stewart, & Murphy, 2004). In addition, Capaldi et al. (2006) found that children are frequently present during violent incidents -- at close to one half of the cases resulting in an arrest for the Oregon Youth Study sample. For couples with a child, education as to the negative consequences of violence for the child may provide motivation to the couple to change their behavior.

As reflected in Figure 2, the findings of our work, along with those of a number of others, have emphasized the importance of studying behaviors of both partners over time to gain an adequate understanding of the phenomena. For example, developmental studies have indicated that conduct problems or antisocial behavior in childhood or adolescence significantly predict later aggression toward a partner for young men as well as young women (e.g., Andrews, Foster, Capaldi, & Hops, 2000; Ehrensaft et al., 2003; Fergusson, Horwood, & Ridder, 2005; Magdol, Moffitt, Caspi, & Silva, 1998; Woodward, Fergusson, & Horwood, 2002). Kim and Capaldi (2004) also found that women’s antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms accounted for significant additional variance in concurrent levels of the young men’s physical and psychological aggression over the man’s own psychopathology. Furthermore, women’s depressive symptoms also had significant effects over time on the young men’s psychological aggression approximately 2 years later. In addition, there was a significant interactive effect of the men and women’s antisocial behavior over time on the young men’s psychological aggression.

The dynamic developmental model can also take into account multiple levels of developmental time in conceptualizing couples’ relationships over time. As discussed, couples’ aggression appears to be related to the age of the partners as well as to the length of the relationship (Capaldi & Crosby, 1997); thus, it is important to consider the potential effects of multiple levels of time on the couples’ behaviors, including each partner’s developmental time, length of the relationship or couple time, and chronological time. Developmental time may have various components (e.g., social maturity, career stage) and may differ for partners even when they are the same chronological age. Developmental time includes some periods of rapid change and others of greater stability. The developmental stage of the couple’s relationship itself -- again related to, but not identical with, the chronological length of the relationship -- may strongly affect the couple’s interactions. For example, early stages may be more marked by insecurity and vulnerability to jealousy, and later stages by more concerns around division of labor and lower levels of satisfaction. The couple’s experience of their relationship and sequencing of events, among other factors, will be experienced in real or chronological time. To adequately conceptualize violence in couples, we must use models that can embrace the changes in context, individual characteristics (e.g., substance use), and the partners themselves (i.e., to a new partner) and conceptualize influences at both the individual and dyadic interaction level. The model must be dynamic to accommodate both development and dyadic interaction.

Recently developed latent class approaches within a developmental framework can be used to combine some of the advantages of a typological approach (e.g., identifying patterns characterizing subgroups of individuals) with approaches to partner violence as an evolving process, rather than as static, and to address intraindividual changes over time (Bushway, Thornberry, & Krohn, 2003; Muthén & Muthén, 2000; Nagin, 1999). The growth mixture modeling approach is not a typology, but is based on a dynamic process conceptualization. This approach has potential to move beyond the current typology work by addressing developmental heterogeneities among individuals and couples. The new developmental approach will inform us about how subgroups of individuals follow distinct longitudinal courses and how partner violence unfolds over time. Concordance across the trajectories of both partners can be examined, or trajectories can be on the basis of the behavior of dyads. Specific knowledge on the etiological mechanisms and developmental processes related to each subgroup can answer critical questions for prevention and intervention by providing information on how partner violence unfolds over time and who is likely to have high levels of partner violence.

Clinical Utility of Batterer Typologies

The idea that batterers typologies would help develop and match specific treatments to specific subgroups of individuals has been emphasized by a number of researchers (e.g., Cavanaugh & Gelles, 2005; Stith et al., 2004). In fact, Saunders (1996) found evidence that feminist-cognitive-behavioral treatment (FCBT) tended to result in more positive treatment outcomes (i.e., lower rates of recidivism) for individuals with antisocial personality characteristics, whereas individuals with dependent personality characteristics tended to benefit more from process-psychodynamic treatment (PPT). This finding suggests that individuals’ personality and psychopathology may be important factors for treatment decision and might be related to different treatment outcomes (Sartin, 2005). This work suggests significant clinical implications of batterer typologies.

Despite the interest in clinical applications, little work has been done in examining whether and how empirically derived subgroups of batterers are useful in clinical settings. There are considerable legal barriers to such applications for court-mandated men. However as a number of the typologies have been based on community samples (e.g. Holtzworth-Munroe et al., 2000), differential treatment tests involving non court-mandated men would be relevant. Many of the typology studies focused on identifying batterer subgroups, and yet none, to our knowledge, addresses treatment options specific to different subtypes of batterers or the efficacy of treatment options for various subtypes of batterers (Babcock, Green, & Robie, 2004). One study examined whether batterer types, identified after study completion for treatment of court-referred samples, were associated with treatment outcomes (Clements, Holtzworth-Munroe, Gondolf, & Meehan, 2000). Findings indicated that the low level Antisocial group was a little more likely to desist from any abuse (including verbal) at 19% desistance versus about 14% for the generally violent antisocial and the borderline dysphoric groups. By 48 months after treatment, all three of these groups showed higher (and similar) re-arrest rates for any violence compared with the family only group. Again, it was not clear that type added to prediction of outcome over what might have been obtained by a single prior severity score.

Currently, to our knowledge, there are no clear assessment procedures developed to identify batterer subtypes for clinical populations. Using the Beck Depression Inventory and the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, Langhinrichsen-Rohling and colleagues (Langhinrichsen-Rohling et al., 2000) compared empirically derived typologies (usually derived from cluster analyses) with theoretically based typologies and found that many of the batterers were classified differently by the two methods. Only 46.9% of the men were classified similarly by the two methods. The best agreement was for the FO group (16 out of 25 men); whereas only 4 out of 19 men and 3 out of 9 men were classified into GVA and BD groups by the two methods. This finding suggests a lack of overlap between empirically based versus theoretically based methods, which causes the authors to question the reliability of typologies. The study also found that mental health professionals (five graduate students) showed difficulties sorting the batterers into the analytically created subtypes when they tried to match individual profiles to the empirically derived subgroups, only 64% of the men were correctly classified into the corresponding empirically derived subgroups.

The study by Langhinrichsen-Rohling et al. (2000) suggests that empirically derived subgroups may not accurately represent individual variations among the men in a given group. Therefore, when the subgroups are determined by mean composites of personality and psychopathology, it would be difficult to determine which batterer belongs to which subgroup (Langhinrichsen-Rohling et al., 2000). Lohr, Bonge, Witte, Hamberger, and Langhinrichsen-Rohling (2005) conducted a further study on the consistency and accuracy of batterer typology identification using experienced clinicians to sort profiles into an empirically derived MCMI-based batterer typology (Hamberger et al., 1996) of three groups, namely negativistic-dependent, antisocial, and nonpathological. Most of the profiles were sorted accurately; however, the raters had the most difficulty sorting some of the “nonpathological” profiles, as 40% were placed in the antisocial cluster and 6% into the negativistic dependent cluster. These findings support the possibility that even the men involved in domestic violence who are considered nonpathological do have some elevated level of antisocial behavior.

Eckhardt, Holtzworth-Munroe, Norlander, Sibley, and Cahill (in press) conducted cluster analyses on a sample of 199 men convicted of a misdemeanor assault offense against an intimate partner to identify partner violence subtypes, using similar measures to Holtzworth-Munroe et al. (2000). As in the Holtzworth-Munroe et al. study, four subtypes were identified showing similar characteristics. However, the men in the BD subtype did not show significantly different mean scores on the MCMI Borderline scale from the GVA subtype. There were considerably fewer men identified as GVA than in the Holtzworth-Munroe et al. (2000) study, even though the latter was of a community sample whereas the Eckhardt et al. study was a court-referred sample. The typology was a stronger predictor of treatment attrition and outcome, however, than a stage of change measure.

In fact, Holtzworth-Munroe and Meehan (2004) have argued that the typological approach has limited application for treatment purposes, because the cut scores generated on one sample may have limited applicability to another sample. They report that replications of their batterer typology have indicated that mean levels of the violent behavior vary considerably by sample and, thus, do not recommend the use of absolute cut-off scores to identify subtypes. Taken together, these findings suggest that it would be very difficult to convert the current typology work into clinical treatment, and the clinical application of the existing typologies has yet to be established.

Implications for Future Research and Clinical Interventions

We recommend that future research on the violence in couples be based on conceptual models that account for the body of evidence that has emerged in the past 20 years. In particular, recently there has been a growing number of prospective developmental studies of couples’ aggression. Such work indicates the need for a dynamic approach that conceptualizes the behavior as involving the process of social interaction of two individuals, each with influence on the other’s behavior, that is embedded in interpersonal contextual influences that show changes over time. As a whole, findings from developmental studies have indicated that we need models that are more open to both intrapersonal as well as interpersonal explanations, and the dynamic developmental model of partner violence was developed to reflect this need.

For clinical applications, it is recommended that both partners’ behaviors are thoroughly evaluated to provide more accurate and effective information regarding the patterns of violence. Although current legal standards may not support this approach, this should not prevent us from recommending effective approaches. Recent studies, including a meta-analytic review, have indicated low effectiveness of batterer treatment programs (Babcock, Green, & Robie, 2004; Jackson et al., 2003). We suggest that clinicians can benefit from adopting the developmental systems perspective. Evaluations of developmental histories and patterns of psychopathology for both partners and other interpersonal contexts within dyads should be part of the assessment. As discussed, recent developmental studies have provided substantial evidence that all of these factors are closely related to partner violence, and these same factors may be related to the treatment outcomes. Even in cases where only one individual is involved in the intervention (e.g., in women’s shelters), the woman can benefit from positive problem-solving techniques, including approaches that avoid initiation and escalation of aggression, such as not using physical violence toward a partner yourself. Such an approach is not victim blaming if general strategies are taught that are helpful for everyone in intimate relationships to both have a successful relationship and avoid violence.

Although relatively scarce, there are a number of treatment and intervention programs that focus on the couple (Hamel, 2005; O’Farrell et al., 2004; O’Leary, 1996). Brannen and Rubin (1996) compared gender specific treatment (GST) with conjoint (couple) treatment for court-mandated men. Both treatments were associated with reductions in physical aggression reported by the wives at posttreatment and 6-month follow up. For couples with a history of alcohol problems, the conjoint approach was more effective. Treatment dropouts were more likely to be from the GST condition. O’Leary, Heyman, and Neidig (1999) compared conjoint therapy with GST for a sample that was not court mandated, but recruited through news advertising. Treatment effects were not significantly different for the two conditions, except that men, although not women, in the conjoint condition showed higher levels of marital adjustment after treatment. Women in the conjoint condition were not more fearful of expressing themselves during treatment or more fearful in general. They were not more likely to experience violence due to participation. Small sample sizes for treatment studies seem to be relatively common and a problematic issue in testing the efficacy of treatment approaches. In the O’Leary et al. (1999) study, the sample size was relatively small, with only a total of 31 couples completing the study, resulting in low power. Thus, although from the reported means, the conjoint condition appeared to be more effective in reducing violence than the GST condition, significant differences were not found. A recent study by Stith et al. (2004), which tested individual couple therapy versus multicouple therapy administered after completion of GST, similarly had only a total of 30 couples complete either condition. Couples treatment approaches for partner violence require modification and further testing, including integrating findings regarding women’s aggression and dyadic process, and testing in efficacy trials with larger sample sizes before conclusions may be drawn about the efficacy of couples’ treatment approaches.

Conclusion

Perhaps one of the most troubling aspects of typological approaches is an unintended side effect. Typologies easily tend to become reified; they are an abstraction--a heuristic device, but tend to become considered to be concrete in clinical and even research applications. Many typology studies focus on identifying the hypothesized subgroups, but their efforts often stop short of extending the work beyond that. Typology studies often apply relatively limited measures to obtain the typologies (e.g., severity and frequency of violence, antisocial personality disorder), and other potentially important risk factors tend to be overlooked. Although many of the typology studies often do not address specific etiologies or mechanisms of partner violence, findings may give the impression, especially for practitioners and for people outside of the field, that the typologies of batterers fully describe the partner violence.

Typological approaches are often viewed as a productive strategy to understanding violence in couples and as the way to move the field forward in this regard. We have argued, however, that both the conceptual and clinical utility of typological approaches seem quite limited. To date, presentations in the field of domestic violence generally emphasize only the value of the typological approach (e.g., Johnson & Ferraro, 2000) without properly addressing the issues addressed above. The batterer typology approach fails to embrace the increasing body of work supporting dyadic models and the influences of time, and it has yet to be converted into more targeted clinical interventions. With the lack of evidence that current typologies are conceptually adequate or clinically feasible, it is important for researchers and clinicians to be aware of issues related to current batterer typologies and to try to broaden the perspective by adopting alternative approaches.

Footnotes

We would like to thank Jane Wilson, Rhody Hinks, and the data collection staff for their commitment to high quality data, Sally Schwader for editorial assistance with manuscript preparation, and Sharon Foster for comments on an earlier draft of this article.

The Cognitive, Social, and Affective Development Branch, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), and Division of Epidemiology, Services and Prevention Branch, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) provided support for the Couples Study (Grant HD 46364). Additional support was provided by Grant MH 37940 from the Psychosocial Stress and Related Disorders Branch, National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), U.S. PHS; Grant DA 051485 from the Division of Epidemiology, Services and Prevention Branch, NIDA, and Cognitive, Social, and Affective Development, NICHD, NIH, U.S. PHS; and Grant MH 46690 from the Prevention, Early Intervention, and Epidemiology Branch, NIMH, and Office of Research on Minority Health, U.S. PHS.

References

- Aldarondo E. Cessation and persistence of wife assault: A longitudinal analysis. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1996;66:141–151. doi: 10.1037/h0080164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Foster SL, Capaldi DM, Hops H. Adolescent and family predictors of physical aggression, communication, and satisfaction in young adult couples: A prospective analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:195–208. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock JC, Green CE, Robie C. Does batterers’ treatment work?: A meta- analytic review of domestic violence treatment outcome research. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;23:1023–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2002.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock JC, Green CE, Webb SA, Graham KH. A second failure to replicate the Gottman et al. (1995) typology of men who abuse intimate partners...and possible reasons why. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:396–400. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.2.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock JC, Miller SA, Siard C. Toward a typology of abusive women: Differences between partner-only and generally violent women in the use of violence. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2003;27:153–161. [Google Scholar]

- Brannen SJ, Rubin A. Comparing the effectiveness of gender-specific versus couples’ groups in a court mandated spouse abuse treatment program. Research on Social Work Practice. 1996;6:405–424. [Google Scholar]

- Bushman BJ, Anderson CA. Is it time to pull the plug on hostile versus instrumental aggression dichotomy? Psychological Review. 2001;108:273–279. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.1.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushway SD, Thornberry TP, Krohn MD. Desistance as a developmental process: A comparison of static and dynamic approaches. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2003;19:129–153. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Crosby L. Observed and reported psychological and physical aggression in young, at-risk couples. Social Development. 1997;6:184–206. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Shortt JW, Crosby L. Physical and psychological aggression in at- risk young couples: Stability and change in young adulthood. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2003;49:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Shortt JW, Kim HK. A life span developmental systems perspective on aggression toward a partner. In: Pinsof W, Lebow J, editors. Family Psychology: The Art of the Science. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 141–167. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Shortt JW, Kim HK, Wilson J, Crosby L, Tucci S. Official incidents of domestic violence: Contexts, impacts, and associations with nonofficial couple aggression. Eugene; Oregon Social Learning Center: 2006. Unpublished manuscript. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh MM, Gelles RJ. The utility of male domestic violence offender typologies: New directions for research, policy, and practice. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2005;20:155–166. doi: 10.1177/0886260504268763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase KA, O’Leary KD, Heyman RE. Categorizing partner-violent men within the reactive-proactive typology model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;3:567–572. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.3.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements K, Holtzworth-Munroe A, Gondolf E, Meehan J. Testing the Holtzworth-Munroe et al. (2000) batterer typology among court-referred maritally violent men.. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy; Reno, NV. 2002. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- DelSol C, Margolin G, John RS. A typology of maritally violent men and correlates of violence in a community. sample. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2003;65:635–651. [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt C, Holtzworth-Munroe A, Norlander B, Sibley A, Cahill M. Readiness to change, partner violence subtypes, and treatment outcomes among men in treatment for partner assault. Violence and Victims. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.4.446. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft MK, Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes E, Chen H, Johnson J. Intergenerational transmission of partner violence: A 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:741–753. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feld SL, Straus MA. Escalation and desistance of wife assault in marriage. Criminology. 1989;27:141–161. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood J, Ridder EM. Partner violence and mental health outcomes in a New Zealand birth cohort. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:1103–1119. [Google Scholar]

- Frieze IH, Browne A. Violence in marriage. In: Ohlin L, Tonry M, editors. Family violence: Vol. 11. Crime and justice: A review of research. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1989. pp. 163–218. [Google Scholar]

- Gelles RJ, Loseke DR. Current controversies on family violence. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gelles RJ, Straus MA. Intimate violence: The causes and consequences of abuse in the American family. New York: Simon and Schuster; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Gendreau PL, Archer J. Subtypes of aggression in humans and animals. In: Tremblay RE, Hartup WW, Archer J, editors. Developmental origins of aggression. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. pp. 25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gondolf EW. Who are these guys?: Toward a behavioral typology of batterers. Violence and Victims. 1988;3:187–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Jacobson NS, Rushe RH, Shortt JW, Babcock J, La Taillade JJ, et al. The relationship between heart rate reactivity, emotionally aggressive behavior, and general violence in batterers. Journal of Family Psychology. 1995;9:227–248. [Google Scholar]

- Graham-Kevan N, Archer J. Intimate terrorism and common couple violence: A test of Johnson’s predictions in four British samples. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18:1247–1270. doi: 10.1177/0886260503256656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene K, Bogo M. The different faces of intimate violence: Implications for assessment and treatment. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2002;28:455–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2002.tb00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger LK, Lohr JM, Bonge D, Tolin DF. A large sample empirical typology of male spouse abusers and its relationship to dimensions of abuse. Violence and Victims. 1996;11:277–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamel J, editor. Gender-inclusive treatment of intimate partner abuse: A comprehensive approach. New York: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Munroe A, Meehan JC. Typologies of men who are maritally violent: Scientific and clinical implications. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19:1369–1389. doi: 10.1177/0886260504269693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Munroe A, Meehan JC, Herron K, Rehman U, Stuart GL. Testing the Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart (1994) batterer typology. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:1000–1019. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.6.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Munroe A, Meehan JC, Herron K, Rehman U, Stuart GL. Do subtypes of maritally violent men continue to differ over time? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:728–740. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Munroe A, Stuart GL. Typologies of male batterers: Three subtypes and the differences among them. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:476–497. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huss MT, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J. Identification of the psychopathic batter: The clinical, legal, and policy implications. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2000;5:403–422. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson S, Feder L, Forde DR, Davis RC, Maxwell CD, Taylor BG. Do batterer intervention programs work? Two studies. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice.; 2003. (NCJ Publication No. 2000331) [Google Scholar]

- Jasinski JL. Trauma and violence research: Taking stock in the 21st Century. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2005;20:412–417. doi: 10.1177/0886260504267880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP. Patriarchal terrorism and common couple violence: Two forms of violence against women. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:283–294. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP, Ferraro KJ. Research on domestic violence in the 1990s: The discovery of differences. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:948–963. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP, Leone JM. The differential effects on intimate terrorism and situational couple issues. Journal of Family Issues. 2005;26:322–349. [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN, McDonald R, Norwood WD, Ezell E. Issues and controversies in documenting the prevalence of children’s exposure to domestic violence. In: Graham-Bermann SA, Edleson JL, editors. Domestic violence in the lives of children: The future of research, intervention, and social policy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 12–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Capaldi DM. The association of antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms between partners and risk for aggression in romantic relationships. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:82–96. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Huss MT, Ramsey S. The clinical utility of batterer typologies. Journal of Family Violence. 2000;15:35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Bromet EJ, Parkinson DK, Day NL, Ryan CM. Patterns of alcohol use and psychically aggressive behavior in men. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1985;46:279–282. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1985.46.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone JM, Johnson MP, Cohan CL, Lloyd SE. Consequences of male partner violence for low-income minority women. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:472–490. [Google Scholar]

- Lohr JM, Bonge D, Witte TH, Hamberger LK, Langhinrichsen-Rohling L. Consistency and accuracy of batterer typology identification. Journal of Family Violence. 2005;20:253–258. [Google Scholar]

- Magdol L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Silva PA. Hitting without a license: Testing explanations for differences in partner abuse between young adult daters and cohabitors. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald R, Jouriles EN, Tart C, Minze L. Child adjustment in the context of men’s severe intimate partner violence: Contributions of other forms of family violence. Poster presented at the meeting of the International Family Violence and Child Victimization Research Conference; Portsmouth, NH. 2006. Jul, [Google Scholar]

- Meehan JC, Holtzworth-Munroe A, Herron K. Martially violent men’s heart rate reactivity to marital interactions: A failure to replicate the Gottman et al. (1995) typology. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:394–408. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.3.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihalic SW, Elliott DA, Menard S. Continuities in marital violence. Journal of Family Violence. 1994;9:195–225. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Muthén LK. Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: Growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:882–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS. Analyzing developmental trajectories: A semiparametric, group-based approach. Psychological Methods. 1999;4:139–157. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell TJ, Murphy CM, Stephan SH, Fals-Stewart W, Murphy M. Partner violence before and after couples-based alcoholism treatment for male alcoholic patients: The role of treatment involvement and abstinence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:202–217. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD. Physical aggression in intimate relationships can be treated within a marital context under certain circumstances. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1996;13:450–455. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD. Developmental and affective issues in assessing and treating partner aggression. Clinical Psychology. 1999;6:400–414. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Barling J, Arias I, Rosenbaum A, Malone J, Tyree A. Prevalence and stability of physical aggression between spouses: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57:263–268. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Heyman RE, Neidig PH. Treatment of wife abuse: A comparison of gender-specific and conjoint approaches. Behavior Therapy. 1999;30:475–505. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Slep AMS. A dyadic longitudinal model of adolescent dating aggression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:314–327. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan HS, Neidig PH, O’Leary KD. Predicting mild and severe husband-to-wife physical aggression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:975–981. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.5.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pence E, Paymar R. Education groups for men who batter: The Duluth model. New York: Springer; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rennison CM. Intimate partner violence and age of victim, 1993–99. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2001. (NCJ Publication No. 19735) [Google Scholar]

- Riggs DS, O’Leary KD. A theoretical model of courtship aggression. In: Pirog-Goood MA, Stets JE, editors. Violence in dating relationships: Emerging social issues. New York: Praeger; 1989. pp. 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Riggs DS, O’Leary KD. Aggression between heterosexual dating partners: An examination of a causal model of courtship aggression. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1996;11:519–540. [Google Scholar]

- Sartin RM. Characteristics associated with domestic violence perpetration: An examination of factors related to treatment response and the utility of a batterer typology. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. 2005;65(8B):4303. (UMI No. AAT 3142099) [Google Scholar]

- Saunders DG. Feminist-cognitive-behavioral and process-psychodynamic treatments for men who batter: Interactions of abuser traits and treatment models. Violence and Victims. 1996;11:393–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slep AMS, O’Leary SG. Examining partner and child abuse: Are we ready for a more integrated approach to family violence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2001;4:87–107. doi: 10.1023/a:1011319213874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stith SM, Rosen KH, McCollum EE, Thomsen CJ. Treating intimate partner violence within intact couple relationships: Outcomes of multi-couple versus individual couple therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2004;30:305–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2004.tb01242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan SC, Snow DL. A typology of women’s use of violence in intimate relationships. Violence Against Women. 2002;8:286–319. doi: 10.1177/1077801206293330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D, Henry DB. Family violence. Annual Review of Psychology. 2006;57:557–583. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tweed R, Dutton DG. A comparison of impulsive and instrumental subgroups of batterers. Violence and Victims. 1998;13:217–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltz J, Babcock JC, Jacobson NS, Gottman JM. Testing a typology of batters. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:658–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RJ, Gondolf EW. Implications of personality profiles for batterer treatment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2000;15:467–488. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward LJ, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Romantic relationships of young people with childhood and adolescent onset antisocial behavior problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:231–243. doi: 10.1023/a:1015150728887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]