Abstract

Over 25 years ago, Kubler-Ross identified anger as a predictable part of the dying process. When the dying patient becomes angry in the clinical setting, all types of communication become strained. Physicians can help the angry dying patient through this difficult time by using 10 rules of engagement. When physicians engage and empathize with these patients, they improve the patient's response to pain and they reduce patient suffering. When physicians educate patients on their normal responses to dying and enlist them in the process of family reconciliation, they can impact the end-of-life experience in a positive way.

Physician-patient interactions involve both biomedical and communication tasks.1 The biomedical tasks are to find and fix the medical problem. The communication tasks are to engage, empathize, educate, and enlist the patient's compliance.2 Angry dying patients can easily overwhelm the communication tasks associated with the normal clinic visit. Physicians frequently are reluctant to engage angry patients. They are not prepared to empathize with the terminal patients. When physicians do not engage and empathize with their dying patients, their efforts to provide adequate analgesia are compromised, and patients suffer unnecessarily.3

Over 25 years ago, Kubler-Ross wrote On Death and Dying.4 This landmark book identified 5 stages in the dying process. Kubler-Ross identified anger as one of those normal stages. This conclusion was based on her clinical work with dying patients. Anger is a predictable part of the dying process. Krigger et al., in “Dying, Death, and Grief,” recommends that physicians accept patient's anger undefensively and provide updated health status reports.5(p265) He articulates that patient's anger tends to resolve with empathetic listening and continued physician involvement.

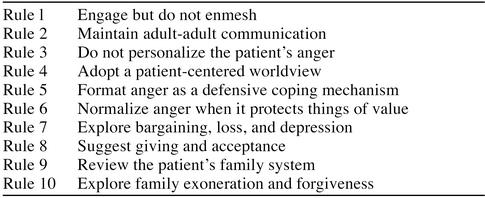

Empathetic listening is a skill that is acquired. Seasoned clinicians change from a biomedical pattern of communication to a psychosocial pattern of communication when patients have emotional distress.6 This change in communication style has therapeutic value.7 Roter and colleagues8 conducted a randomized field trial that established that physicians could improve their listening skills and switch communication styles when patients have emotional needs. I suggest 10 communication techniques for reaching out to the angry dying patient (Table 1).

Table 1.

Rules for Engaging the Angry Dying Patient

ENGAGE BUT DO NOT ENMESH

Engagement can be thought of as a communication technique that creates relationship.9 Relationship has behavioral and emotional components. In emotionally intense clinical settings, clear emotional boundaries are valuable. They respect the patients' capacity to process their own emotions, and they protect the physician's emotional well being.10

Some physician statements take ownership for patient feelings: “I feel bad for you.” These statements create confusion about who will do the emotional work in the dying process. This is called an enmeshed relationship.11 Physicians who want to help dying patients have to be honest about who will do the emotional work. Physicians should offer support this way: “If I were in your situation, I would certainly feel upset.” This language is engaging, but patients are encouraged to process their own anger, fear, sadness, and loneliness.

MAINTAIN ADULT-ADULT COMMUNICATION

The basic family communication patterns are adult-child and adult-adult.12 Paternalistic physicians frequently use adult-child communication; the physician has power and the patient does not. Power distribution in the adult-adult communication is equal. Physicians should empower dying patients and reorient them into the adult-adult world.

The caring physician should enter the dying patient's world with skill.13 These patients experience progressive loss and disability. Adult-child communication heightens that sense of regression and powerlessness. Paternalistic physicians should not be shocked when patients focus their anger at them. Their communication style may be precipitating the emotional outburst. The astute physician will identify the problem, apologize, and switch to adult-adult communication.

DO NOT PERSONALIZE THE PATIENT'S ANGER

Angry patients frequently try to blame someone for their disposition: “You missed my cancer diagnosis.”14 They succeed when they transfer ownership for their emotional state to someone else. Psychiatrists call this coping style projection.15 Patients who project their anger are difficult to engage. Physicians can remain engaged if they frame this behavior as a dysfunctional coping style used in an emotionally intense situation.16

Most physicians are tempted to respond to projected emotion with equally intense emotion: “You ignored your cancer symptoms for 6 months.” These responses are usually counterproductive. Consider how the patient might act under less stress. Their low stress solicitation may be, “My cancer pain is really bad today.” De-escalate the emotional situation by responding to the suspected “low stress” solicitation: “How bad is your cancer pain today?”17

This clarification question acknowledges the patient's emotional state and solicits adult-adult communication on the subject.18 It deflects the patient's anger, and then the physician can rationally explore causes of the patient's anger.

ADOPT A PATIENT-CENTERED WORLDVIEW

Physicians who show a genuine interest in their patients form deeper relationships.19 Most angry dying patients will cooperate with their physician's attempts at life review and life validation.12 Life review questions include: “Tell me about your life,” “What about that incident was important to you?” Life validation is an interpretive process: “So you were the reluctant family matriarch? That is an important role.” These techniques develop physician-patient understanding, and they usually reduce patient anger.

Life review and life validation can also help physicians discover their patients' values. Physicians who understand these values can relate on a deeper level.19 They can also use a technique called substituted judgment to improve patient trust.20 This technique mandates an honest physician appraisal of the patient's situation and a promise to act on the patient's values in the future: “If I was in your situation, I would want my physician to act on my values. Tell me about your priorities, concerns, and hopes.” Patients quickly realize that this contract increases patient control and context during the dying process.

FORMAT ANGER AS A DEFENSIVE COPING MECHANISM

Life leaves the body in one of two ways: it is taken from us or we let it go. When life is taken from us as a series of personal violations, we will naturally protect ourselves. Cancer and other terminal illnesses invade patients' personal lives.21 One can argue that these invasions are morally reprehensible. Using this argument, the patient and the physician can mutually ventilate their righteous anger at the disease process.22 By redirecting patient anger toward the illness, the physician can rescue family members from a deluge of projected emotion.

NORMALIZE ANGER WHEN IT PROTECTS THINGS OF VALUE

Patients frequently express shock, shame, or embarrassment after emotional outbursts: “I do not know what came over me. That was not like me!” If the patient's religious or cultural background inhibits the expression of internalized anger, the physician may need to guide the patient through a value evaluation process. Righteous anger can usually be integrated into the patient's value system as a natural response to patient suffering.23 This reevaluation process is called normalization. Normalizing anger can help patients embrace and move through the anger stage of the dying process.

Physicians who understand their patient's value system can offer an honest appraisal of the patient's anger. They can format anger as a natural defensive response to the violations that illness has created in their patient's life. Suffering can be defined as the “cognitive loss of something of value.”24 Physicians then can explore with their patient: “What things of value has your illness taken from you? What does your anger defend?” These questions help patients discover and share their internalized anger and loss. This in turn reduces patient suffering.

EXPLORE BARGAINING, LOSS, AND DEPRESSION

Kubler-Ross' work is a valuable road map of the patient's normal emotional responses to dying. The clinician can use this map in a therapeutic manner. The angry patient can be encouraged to transition to the third stage of dying: bargaining. Physicians may encourage bargaining with statements like: “We will beat the cancer.” This physician attitude moves patients away from their anger, but it should be used sparingly. Patients who arrest in the bargaining stage frequently make unrealistic bargains with God, family, or physician. Each physical setback may then become a “broken contract.” This can increase patient suffering and damage trust.

Clinical interventions can be designed to facilitate the patient who has arrested in a particular stage. I encourage angry and bargaining patients to inventory their personal losses. Sadness is the normal emotional response to personal loss and is the emotion frequently associated with depression. Focusing on losses helps angry and bargaining patients move on toward and through depression. Sympathetic listening and sharing skills can influence the patient's perception of personal losses, and this can minimize depression.25 The physician should avoid solving problems.26 They should listen, paraphrase, and share.

SUGGEST GIVING AND ACCEPTANCE

Our hospice team does not advocate any particular religion, but we do not ignore the spiritual aspects of dying.27 Zen Buddhists preach on a “giving away” process called Ju.28 Judo is a discipline that is based on the Do, “the way,” of Ju, “giving away.” It is a discipline of self-defense, gentleness, and weakness. Christians speak of Jesus' amazing grace. Grace is a gift-giving process, and it is a cornerstone of Christianity.29 Both of these world religions endorse a process of “giving away.”

The physician should explore patients' spiritual paradigms and help them reframe their losses as gifts, if possible. Integrity can be preserved within the family's broader context.30 Power can be transitioned to loved ones and trusted friends. Life is not lost; the torch is handed off. Relationships can be renewed, and family meaning can be preserved. This technique can help families minimize the suffering and sense of loss that are associated with the dying process.

REVIEW THE PATIENT'S FAMILY SYSTEM

The process of dying is not isolated to the patient and the patient's body. The dying process is also a family and social process.31 The patient's family system changes with the progressive disability that accrues with the illness. Familiar family dynamics are challenged, and new family dynamics emerge in the process. Dysfunctional families frequently become more dysfunctional. Old unresolved family conflicts emerge as the patient's condition deteriorates. These conflicts may present as inappropriate patient anger toward the physician, staff, and family.

The patient should be educated about normal family transitions at the end of life. Then that patient should be enlisted to facilitate those transitions when reasonably possible.32 A family history must be solicited from the patient and the family members. Family conflict should be identified as a frequent and normal part of any change within a family system.

EXPLORE FAMILY EXONERATION AND FORGIVENESS

Exoneration and forgiveness are two powerful tools that the physician can use to reconcile families at the end of life.12 When physicians successfully intervene to create a sense of exoneration at the time of death, they impact family function for generations. Exoneration is achieved when a dying family member's past behaviors are understood as intergenerational obligations. A clear example of exoneration based on intergenerational obligations occurs with motherhood. A new mother discovers that the obligations of motherhood dictate the very behaviors that she disliked in her mother. This understanding exonerates her mother's behavior.

Forgiveness is frequently a valuable intervention for the injured survivors of a dysfunctional family system.12 When childhood injuries exceed the norms of intergenerational obligations, then anger within the family can escalate as the patient's death approaches. If the family physician senses this unresolved injury, he can act to facilitate forgiveness within the family system. When a physician is facilitating this process, he should acknowledge a family injustice and solicit voluntary forgiveness for the unresolved injury.

SUMMARY

The angry dying patient is a challenge for any clinician. The 10 rules for engaging the angry dying patient can help physicians overcome the common obstacles associated with these patients' care. Dying is an emotional time for patients and their families. The physician that is willing to engage and empathize with the dying patient is more likely to enlist the patient's help in achieving closure on important family issues. Physicians can use these rules to extend themselves in a meaningful way to the angry dying patient. Hippocrates said: “Where there is love of mankind, there is also a love of this art.”33(p89) When clinicians have the skill and commitment to make a difference in end-of-life care, they impact patients' lives in a positive manner.34

REFERENCES

- Epstein RM, Campbell TL, Cohen-Cole SA, et al. Perspectives on patient-doctor communication. J Fam Pract. 1993;37:377–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinician-Patient Communication to Enhance Health Outcomes. West Haven, Conn: Bayer Institute for Health Care Communication. 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manetto C, McPherson S. The behavioral-cognitive model of pain. Clin Geriatr Med. 1996;12:461–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubler-Ross E. On Death and Dying. New York, NY: Macmillan. 1969 [Google Scholar]

- Krigger D, NcNeely D, Lippmann S. Dying, death, and grief. Postgrad Med. 1997;101:263–270. doi: 10.3810/pgm.1997.03.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roter DL, Stewart M, Putnam SM, et al. Communication patterns of primary care physicians. JAMA. 1997;277:350–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel EJ, Emanuel LL. Four models of the physician-patient relationship. JAMA. 1992;267:2221–2226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roter DL, Hall JA, Kern DE, et al. Improving physicians' interviewing skills and reducing patients' emotional distress: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1877–1884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouch M, Roberts L. The Family in Medical Practice: A Family Systems Primer. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag. 1987 [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin S. Families and Family Therapy. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. 1978 [Google Scholar]

- Scheingold L. Balint work in England: lessons for American family medicine. J Fam Pract. 1988;26:315–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargrave T, Anderson W. Finishing Well. New York, NY: Brunnel/Mazel. 1991 [Google Scholar]

- Coleman WL. The first interview with a family. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1995;42:119–129. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)38912-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns JW, Johnson BJ, Mahoney N, et al. Anger management style, hostility and spouse responses: gender differences in predictors of adjustment among chronic pain patients. Pain. 1996;64:445–453. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin S, Nichols M. Family Healing: Strategies for Hope and Understanding. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Doherty W, Baird M. Family Therapy and Family Medicine. New York, NY: Guilford Press. 1983 [Google Scholar]

- Stuart M, Lieberman J. The Fifteen Minute Hour, Applied Psychotherapy for the Primary Care Physician. Westport, Conn: Praeger. 1993 [Google Scholar]

- Doherty W, Baird M. Developmental levels in family-centered medical care. Fam Med. 1986;18:153–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp T, Childress J. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Streim J, Marshall J. The dying elderly patient. Am Fam Physician. 1988;38:175–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldridge R, Waldridge R. Delivering bad news to patients and their families. Fam Pract Manage. 1996 Sep;:48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Masson J, McCarthy S. When Elephants Weep. New York, NY: Delacorte Press. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- Frankl V. In Man's Search For Meaning. New York, NY: Washington Square Press. 1984 [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz D, Walsh M, Gabel LL, et al. Family physicians' involvement with dying patients and their families: attitudes, difficulties, and strategies. Arch Fam Med. 1993;2:753–760. doi: 10.1001/archfami.2.7.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry J, D'Epiro NW. When men and women speak. Fam Pract Manage. 1995 Jan;:42–49. [Google Scholar]

- King D, Bushwick B. Beliefs and attitudes of hospital inpatients about faith, healing, and prayer. J Fam Pract. 1994;39:349–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross N. Three Ways of Asian Wisdom. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. 1966 [Google Scholar]

- Romans. 5:15–17.(NIV). [Google Scholar]

- Patterson JM, Garwick AW. Levels of meaning in family stress theory. Fam Process. 1994;33:287–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1994.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh F. Normal Family Processes. New York, NY: Guilford Press. 1982 [Google Scholar]

- Taylor R. Family Medicine Principles and Practice. 4th ed. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag. 1993 [Google Scholar]

- Brown A. The Physician Throughout the Ages. New York, NY: Capehart-Brown. 1928 [Google Scholar]

- Byock IR. The nature of suffering and the nature of opportunity at the end of life. Clin Geriatr Med. 1996;12:237–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]