Abstract

Postpartum depression (PPD) is an irritable, severely depressed mood that occurs within 4 weeks of giving birth and possibly as late as 30 weeks postpartum. Manifestations include crying spells, insomnia, depressed mood, fatigue, anxiety, and poor concentration. Patients may experience mild, moderate, or severe symptoms. Many psychosocial stressors may have an impact on the development of PPD. Recent studies conclude that the majority of factors are largely social in nature. The greatest risk is in women with a history of depression or other affective illness and in those who have experienced depression during past pregnancies. Women with significant risk factors should be followed closely in the postpartum period.

The severity of symptoms and degree of impairment guide the approach to treatment. Treatment should begin with psychotherapy and advance to pharmacotherapy if needed; however, many patients benefit from concomitant treatment with both psychotherapy and medication. Common forms of psychotherapy include interpersonal therapy and short-term cognitive-behavioral therapy. Postpartum depression demands the same pharmacologic treatment as major depression does, with similar doses as those given to patients with nonpuerperal depression. It is essential to use an adequate dose of antidepressants in a duration sufficient to ensure complete recovery. Mothers should continue medication for 6 to 12 months postpartum to ensure a complete recovery.

Inadequate treatment of depression puts women at risk for the sequelae of untreated affective illness, and the depression may become chronic, recurrent, and/or refractory. Family physicians are key players in the detection and treatment of PPD owing to the nature of the disease and the tendency for new mothers to negate their feelings as something other than a treatable psychiatric illness.

KEY QUESTIONS

This article seeks to answer the 3 following key questions: (1) How does postpartum depression present in a primary care setting? (2) How can patients be screened for postpartum depression? (3) What is the optimal treatment plan for patients with postpartum depression?

CASE PRESENTATION

A 28-year-old primiparous married patient delivered a healthy child at term. During the 8 weeks following the birth, she felt fatigued, irritable, sluggish, weepy, and worthless. Additionally, she lost her appetite, though she forced herself to eat because she was committed to breastfeeding. She felt guilty because she perceived that she should be happier at this time in her life, and she was reluctant to disclose her feelings to her physician.

DEFINITIONS

Postpartum blues are defined as a depressed mood experienced shortly after birth.1 This disorder develops in 50% to 70%1 of all women following childbirth, beginning at day 3 or 4 and usually ending within 2 weeks. Manifestations include crying spells, insomnia, depressed mood, fatigue, anxiety, and poor concentration.

Postpartum depression may have symptoms like postpartum blues, as well as irritability and a more severely depressed mood.

Postpartum psychosis is a very rare occurrence2 (1–2 per 1000 deliveries) and has clinical features including mania, psychotic thoughts, severe depression, and other thought disorders. It is a psychiatric emergency and requires referral and hospitalization.

SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM

Is postpartum depression (PPD) part of the same syndrome as major depression, or is it a separate entity? This controversy is debated throughout the literature.2,3 According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV),4 PPD is not a separate entity, but exists as a part of the spectrum of major depression, coded with a modifier for postpartum onset. DSM-IV stipulates that the onset must be within 4 weeks of delivery of a neonate. Previously, this disorder had been thought of as part of a spectrum of illnesses related distinctly to pregnancy and childbearing, and therefore a distinct diagnostic entity. Recent evidence suggests that PPD may not differ significantly from other affective disorders occurring in women, but that subgroups of women may be at increased risk for developing or experiencing a recurrence of affective illness in the postpartum period. The greatest risk seems to be in women with a history of depression or other affective illness5 or those who have experienced depression during past pregnancies.6

The incidence of the problem has been reported from as low as 8% to as high as 23% nationally.7 Most epidemiologic studies have not used the strict criteria of onset within 4 weeks, as stipulated by the DSM-IV.4 The inconsistencies in the time frame used for diagnosing PPD make the literature, at least epidemiologically, difficult to interpret. In fact, there have been several published reports that suggest the highest risk time frame for onset of PPD is within the first 3 months postpartum.6,8

According to Stuart et al.,7 anxiety and PPD frequently coexist. The prevalence of anxiety was found to be 8.7% at 14 weeks postpartum and 16.8% at 30 weeks postpartum. The incidence during the time frame of 14 to 30 weeks postpartum was found to be 10.28%. This rate was actually higher than the incidence of PPD during the same time frame (14 to 30 weeks postpartum incidence was 7.48%), demonstrating a significant number of new cases of anxiety and depression developing as late as 3 to 7 months postpartum.7 The numbers in this particular study suggest that clinicians need to be alert to the possibility that PPD may develop as late as 30 weeks postpartum.

SCREENING FOR POSTPARTUM DEPRESSION

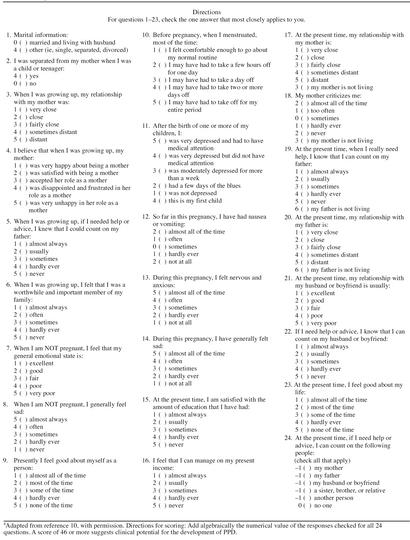

Many methods have been tried and tested to screen women in the antenatal period for the possibility of developing PPD. One of the most frequently mentioned methods of screening is the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). It is a simple 10-question screen initially proposed by Cox et al. in 1987.9 The Antepartum Questionnaire (APQ), developed more recently by Posner et al.,10 demonstrates a sensitivity of 80% to 82% and a specificity of 78% to 82% (Table 1). In the studies developing the APQ, the rate of PPD rose from 10% to 17% from delivery to 6 weeks postpartum. The number of women who demonstrated more than mild depressive symptoms also continued to rise until approximately 12 weeks postpartum. Clinically, this screening technique appears to have usefulness.

Table 1.

Antepartum Questionnairea

According to Posner et al.,10 any antepartum patient scoring 46 or greater on the APQ should be considered for psychiatric evaluation and followed closely during the postpartum period to detect possible signs of PPD. Of particular concern is the number of women who continue to have worsening depressive symptoms over time or those whose symptoms go undetected and untreated. A family physician can easily incorporate PPD screening into practice, since closer follow-up of the mother is possible while concurrently caring for the infant during well-child visits.

The aforementioned patient came from a single-parent family, was married to a medical student, and had just moved to a new city (away from her family) for her husband to start his residency. She was unemployed, although she previously had a fairly successful job in real estate. Her initial symptoms began the fourth week postpartum, but it was not until the tenth week that she sought attention for her worsening symptoms. She saw her primary physician for a 6-week follow-up appointment, but was too embarrassed to bring up her concerns. Her primary care physician failed to ask any questions regarding PPD.

RISK FACTORS

The time following the birth of a child is one of intense physiologic and psychological change for a new mother. While many studies have looked at possible etiologies, including hormonal fluctuation,11–13 biological vulnerability,5 and psychosocial stressors,14 the specific etiology of PPD remains unclear. It is possible that no biological factors are specific to the postpartum period, but that the process of pregnancy and childbirth represents such a stressful life event that vulnerable women experience the onset of a depressive episode. Many psychosocial stressors have been demonstrated to have an impact on the development of PPD. In fact, many recent studies have found that the majority of important factors are largely social in nature.6 Beck15 reported the following predictors for PPD after conducting a meta-analysis to identify women at risk for developing PPD.

Prenatal depression: Depression during pregnancy was discovered to be a significant predictor, independent of the trimester it occurred.

Child care stress: Included related stressful events involved in the care of the newborn, especially the temperament of infants who may be fussy, irritable, and difficult to console. Also of significance in this category are those infants with health troubles.

Support: Included in this domain are such factors as social support, emotional support, and instrumental support (i.e., help at home). The lack of support may be either real or perceived by the patient.

Life stress: This stress is related to the number of stressful life events that occur during both pregnancy and the postpartum period. The stressors may be either positive or negative.

Prenatal anxiety: As mentioned previously, anxiety is highly prevalent in the PPD patient.7 There may be a generalized feeling of uneasiness about an obscure, nonspecific threat.

Marital dissatisfaction: This is an assessment by the patient regarding her level of happiness and satisfaction with not only her marriage/relationship in total, but also any specific aspect of the relationship.

History of previous depression: A personal history of affective illness increased the risk of developing PPD.12 The relapse rate has been reported as high as 50%16 if previous episodes of PPD were experienced, whereas the development of PPD in women with a history of major depression is less clear.5,6

Regarding the possibility of biological predictors, the presence of postpartum blues has been found in several studies to be related to the eventual development of PPD.17 The association for most biological variables thought to be etiologic has been negative or contradictory. There have been multiple method problems with many hormonal influence studies, including assessment of total hormone concentration rather than active hormone levels. In general, these studies also fail to measure the degree of change of free hormone from pregnancy to early postpartum and do not control for breastfeeding. Assessing the hormonal influence on the development of PPD is thus limited at best.

Since there are no clear-cut predictors of who will develop PPD (although subgroups of women are described in the literature), it would seem advisable to screen all women for depression during both the antepartum and postpartum periods.

DIAGNOSIS

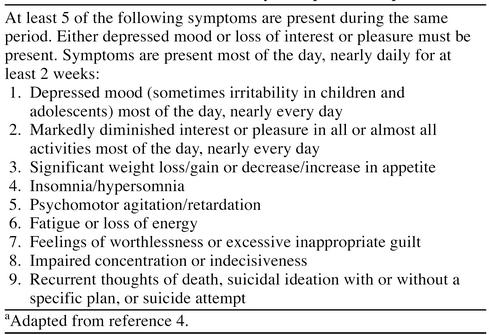

Health care professionals, including nurses, doctors, and social workers, are often unaware of maternity problems that women can experience.18 Postpartum depression is frequently missed by the primary care team. Since the clinical signs of this disorder are not apparent unless screened for, assessment at every chance is key. There are multiple screening techniques, including the EPDS and the APQ. The EPDS has been shown to have a specificity of 92%, a sensitivity of 88%, and a positive predictive value of 35%.8 Since PPD is classified by DSM-IV as a part of the spectrum of major depression, the criteria for this disorder can also be used when screening for PPD (Table 2).4

Table 2.

DSM-IV Criteria for a Major Depressive Episode

Patient education about PPD is also a big factor in diagnosis. New mothers may tend to feel ashamed when they are not overjoyed with the birth of a new child and may not report symptoms or problems to their primary care provider. Antepartum education about the symptoms of PPD to both parents may better prepare them for upcoming challenges and make them both more aware of a practical approach to PPD.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

There are a number of physiologic as well as pathologic problems that may present as symptoms similar to depression. The most common problems may be a result of transient hypothyroidism and anemia. Transient hypothyroidism occurs in 4% to 7% of patients and peaks 4 to 6 months postpartum.19 Thyrotoxicosis can present with symptoms suggesting panic disorder. Other problems may include other endocrine disorders, abuse situations, and infection. Although there are many social and physical changes associated with the postpartum period, the primary care team must keep a watchful eye, especially when there are behavioral changes in the mother.

TREATMENT

Postpartum blues are generally self-limited and resolve between 2 weeks and 3 months.17 Since symptoms resolve spontaneously, supportive reassurance is the limit of usual therapy. Medication is usually unnecessary.

Like other forms of depression, PPD occurs along a continuum. Patients may experience mild, moderate, or severe symptoms. Approach to treatment must be guided by the severity of symptoms and the degree of impairment.

First-line therapy is psychotherapy. Two methods of therapy that have been shown to be beneficial are interpersonal therapy (IPT) and short-term cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).17 IPT is a time-limited and interpersonally oriented psychotherapy and may be effective for women with mild depression. CBT teaches people to recognize their inaccuracies in thinking, thereby arriving at a more realistic view of the world. This approach to therapy is more beneficial if anxiety is a strong component of symptoms.20 There are many patients who will benefit from treatment using both psychotherapy and medication.

Second-line therapy is pharmacotherapy. There are patients who will require medical treatment. Since there are no defined data on treatment, PPD demands the same treatment as major depression,17 with similar periods of time and similar doses as nonpuerperal depression. There has been a tendency to treat PPD less aggressively than other affective disorders in both duration of therapy and dose. However, inadequate treatment of PPD puts women at risk for the sequelae of untreated affective illness, and the depression may become chronic, recurrent, and/or refractory. As in other forms of affective disorders, pharmacotherapy should be combined with counseling or support groups or both. Mothers should continue medication for 6 to 12 months postpartum to ensure a complete recovery.

No antidepressant has been approved as a category A agent for use during pregnancy or lactation.21–23 However, in patients with signs of depression, including sleep and appetite changes, poor concentration, or psychomotor changes, antidepressants are indicated.3 Only a few studies have evaluated antidepressants in the postpartum patient.24 In all of these studies, the same dosing schedule used for other forms of depression was therapeutic and well tolerated. All women who are breastfeeding must be informed that all antidepressants are secreted in breast milk in varying amounts.21–23,25 Neonatal exposure seems to have a low rate of side effects; however, long-term effects on the developing brain are unknown.

With the large shifts in hormonal factors in the postpartum period, it would stand to reason that there may be a possibility of treating PPD with hormonal therapy. Several authors suggest progesterone therapy, but no data currently support the use of progesterone in PPD. Recent studies have described the benefits of transdermal estrogen, either alone or in combination with an antidepressant in the treatment of PPD.26 According to Cohen and Rosenbaum,27 the use of tricyclic antidepressants should not pose a risk when used in pregnancy (not teratogenic even in the first trimester) or in the postpartum period. He maintains that the safest medications to use at this point in time are nortriptyline, imipramine, and fluoxetine. Choosing an antidepressant for each patient should correlate to the most remarkable symptoms, as in major depression. Dosing schedules are equivalent to dosing used in major depression not associated with pregnancy or the postpartum period. Initial treatment regimens can be increased according to the resolution of symptomatology.

In patients at risk of suicide, or with active suicidal ideation, referral and hospitalization are necessary. Severe PPD has been shown to respond rapidly to electroconvulsant therapy.28

Optimal treatment for our patient at this time would be initiation of psychotherapy. If optimal results were not attained in a predetermined time period, medication would be the next line. If her symptoms worsen before the therapy time frame is up, the consideration of medication must come sooner. The patient in this case received IPT, with some improvement. She was also started on 10 mg/day of fluoxetine. She had improved sleep, modestly improved appetite, and modestly improved energy levels. Her libido remained at a low level. All symptoms were markedly improved with an increase of the medication dose to 20 mg/day and continuation of several weeks of psychotherapy.

CONCLUSION

Due to the nature of PPD and the tendency for new mothers to negate their feelings as something other than a treatable psychiatric illness, it seems that family physicians are key players in the detection and treatment of this disease. The opportunity to educate parents and follow the behavioral changes in the mothers is an available tool to the primary care physician. Because of the prevalence of PPD, all physicians who care for obstetric patients as well as children should develop a method for screening for depressive symptoms. Women who have significant risk factors will need to be followed more closely in the postpartum period. If a woman meets DSM-IV criteria for PPD, attempts at treatment should begin with psychotherapy and advance to pharmacotherapy if indicated. As in treating other affective disorders, it is essential to use a high enough dose of antidepressants and use them in a duration sufficient to ensure complete recovery.

Drug names: fluoxetine (Prozac), imipramine (Tofranil and others), nortriptyline (Pamelor and others).

REFERENCES

- O'Hara MW, Schlechte JA, Lewis DA, et al. Prospective study of postpartum blues: biologic and psychosocial factors. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:801–806. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810330025004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendell RE, Chalmers JC, Platz CA. Epidemiology of puerperal psychoses. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:662–673. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.5.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diket AL, Nolan TE. Anxiety and depression: diagnosis and treatment during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1997;24:535–558. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8545(05)70321-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 1994 317–391. [Google Scholar]

- O'Hara MW, Schlechte JA, Lewis DA, et al. A controlled prospective study of postpartum mood disorders: psychological, environmental, and hormonal factors. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100:63–73. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hara MW, Neunaber DJ, Zekoski EM. A prospective study of postpartum depression: prevalence, course, and predictive factors. J Abnorm Psychol. 1984;93:158–171. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.93.2.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart S, Couser G, Schilder K, et al. Postpartum anxiety and depression: onset and comorbidity in a community sample. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998;186:420–424. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199807000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper P, Murray L. Prediction, detection, and treatment of postnatal depression. Arch Dis Child. 1997;77:97–99. doi: 10.1136/adc.77.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner NA, Unterman RR, Williams KN, et al. Screening for postpartum depression: an antepartum questionnaire. J Reprod Med. 1997;42:207–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris B. A hormonal component to postnatal depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;163:403–405. doi: 10.1192/bjp.163.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris B. Biological and hormonal aspects of postpartum depressed mood. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;164:288–292. doi: 10.1192/bjp.164.3.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick V, Altshuler LL, Suri R. Hormonal changes in the postpartum and implications for postpartum depression. Psychosomatics. 1998;39:93–101. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(98)71355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey AR, Boyce PM, Ellwood D, et al. Early discharge and risk for postnatal depression. Med J Aust. 1997;167:244–247. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb125047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck CT. A checklist to identify women at risk for developing postpartum depression. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1998;27:39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1998.tb02589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisner KL, Wheeler SB. Prevention of recurrent postpartum major depression. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994;45:1191–1196. doi: 10.1176/ps.45.12.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonacs R, Cohen LS. Postpartum mood disorders: diagnosis and treatment guidelines. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 2):34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowbray CT, Oyserman D, Zemencuk JK, et al. Motherhood for women with serious mental illness: pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1995;65:21–38. doi: 10.1037/h0079588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman JM. Postpartum thyroid dysfunction. Arch Intern Med. 1986;146:1296–1299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassem NH. Massachusetts General Hospital Handbook of General Psychiatry. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby-Year Book. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- Prozac (fluoxetine). Physicians' Desk Reference. Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics. 1998 859–863. [Google Scholar]

- Pamelor (nortriptyline). Physicians' Desk Reference. Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics. 1998 1889–1890. [Google Scholar]

- Tofranil (imipramine). Physicians' Desk Reference. Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics. 1998 1908–1910. [Google Scholar]

- Schou M. Treating recurrent affective disorders during and after pregnancy: what can be taken safely? Drug Saf. 1998;18:143–152. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199818020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisner KL, Perel JM, Findling RL. Antidepressant treatment during breastfeeding. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:1132–1137. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.9.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowe ZN, Nemeroff CB. Women at risk for postpartum-onset depression. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:639–645. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90296-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LS, Rosenbaum JF. Psychotropic drug use during pregnancy: weighing the risks. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 2):18–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregoire AJ, Kumar R, Everitt B, et al. Transdermal oestrogen for treatment of severe postnatal depression. Lancet. 1996;347:930–933. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91414-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]