Abstract

Background and Objectives: One of the skills required of family physicians is the ability to recognize and treat individuals suffering from mood disorders. This study represents an interdisciplinary residency training approach that (1) is unique in family practice residencies; (2) trains faculty, residents, and students in mood disorder recognition and treatment; (3) has been evaluated by the Residency Review Committee and found compatible with psychiatry training guidelines; and (4) is adaptable to varied settings.

Method: Existing psychiatric education at an urban family practice residency program was evaluated. A new curriculum was developed to emphasize clinical interactions that would allow residents to model the behavior of family physicians who demonstrate interest and expertise in psychiatry. The centerpiece of this curriculum is a family-physician–led, multidisciplinary, in-house consultation service known as a mood disorders clinic (MDC). Educational effectiveness was evaluated by comparing resident identification rates of mood disorders before and after training. Educational utility was evaluated by implementation in a variety of settings.

Results: Fifty-one residents rotated through 1 or more of 3 practice sites during a 60-month period. Psychiatric diagnoses for the 187 patients who remained in treatment for complete clinical assessment included all major mood and anxiety disorders outlined in the DSM-IV. A wide variety of associated psychosocial problems were also identified. A significant difference (p < .05) was seen between the number of continuity patients diagnosed with psychiatric conditions by resident physicians before and after the training experience.

Conclusion: Implementation of this intensive training experience resulted in subjective as well as objective enhancement of resident education by providing an intensive, focused educational experience in primary care psychiatry. This concept is adaptable to a variety of practice sites and educational levels. The MDC could become the hub of an integrated delivery system for mental health services in an ambulatory primary care setting.

Family practice embraces a broad and holistic range of skills centered on comprehensive patient care. Managed care, other efforts at cost containment, and family physician shortages highlight the need for comprehensive clinical and administrative skills. Areas of needed clinical proficiency include internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, geriatrics, procedural skills, and preventive medicine, among others. Proficiency in psychiatry is also required. Indeed, given the prevalence1,2 and dysfunction3,4 associated with mood disorders, teaching family physicians to recognize, assess, and treat depressed and anxious patients should be given high priority.5 However, investigations show that the recognition and treatment of psychiatric disorders by primary care physicians varies greatly and is generally lacking.6,7 Physician attitude, the stigmata of mental illness, time constraints of practice, and deficient education may all contribute to this problem.

A broadly and properly trained family physician is, perhaps, uniquely able to integrate biological, psychological, and social data into a meaningful patient assessment and treatment plan. Clearly, intense educational efforts focused on these common clinical situations will be needed to close the current gap between theory and practice for family physicians. It seems just as clear, however, that current efforts are not producing the desired results.

Clinical precepting by family practice faculty, rotational experiences with psychiatrists or other mental health providers, and didactic sessions with professionals in both of these disciplines are all reasonable instructional strategies to teach psychiatry to family practice residents. The goal for the present effort was to develop a more intensive training experience than was possible using the more traditional educational components.

The Department of Family Medicine at the University of Tennessee, Memphis, had previously addressed a similar educational challenge in the area of office procedures (e.g., endoscopy and ultrasound) by developing an in-house procedure suite. This service allocated blocks of time for scheduled procedures, providing an intensive learning experience.8 Residents were supervised by family physician faculty members experienced in these procedures, and concentrated patient encounters encouraged the rapid acquisition of specific skills. It was reasoned that a similar learning environment might be well suited for teaching psychiatry also.

This article describes the development and pilot implementation of a mood disorders clinic (MDC)—an intensive, in-house, clinically based component for resident training to treat mood disorders. A discussion of the needs assessment, curriculum development, establishment of training sites, and program evaluation is included.

METHOD

Needs Assessment

The needs assessment that led to the development of this curriculum is based on the prevalence and competency data mentioned earlier, a practice chart review revealing a deficient rate of mental health diagnoses (present in less than 4% of all charts), and the recommendations of a curriculum committee. The Department's previous behavioral medicine training combined traditional block rotation components (didactic teaching, visits to community resource agencies, interaction with community psychiatrists) with longitudinal precepting by faculty physicians. While these activities continue to be important components of the current training program, 2 distinct areas for improvement were targeted relating to identifying and treating patients with mood disorders.

Longitudinal training is important, but residents may require months or even years of training using this method before feeling confident of their ability to treat psychiatric problems and translating that confidence into practice. This instructional strategy also risks exposing residents to differing and perhaps conflicting management styles by several faculty physicians with varied levels of interest and expertise in the area of psychiatry. While a longitudinal approach promotes educational diversity, it does not ensure rapid development of a data-driven cohesive knowledge base, nor does it promote clinical consistency. The curriculum needed to be implemented early in the residency in a way that provided both intensity and consistency.

Affiliation with local psychiatrists can provide excellent exposure to the care and treatment of individuals with identified psychiatric problems. Treating psychiatric disorders in primary care settings, however, is different from that of psychiatric settings in a number of ways. Patients in primary care settings typically present with somatic complaints that may represent unrecognized psychiatric problems. In addition, individuals experiencing emotional distress may choose to see a primary care provider rather than a mental health professional because of an unwillingness to acknowledge a psychiatric diagnosis. Finally, those who act on referrals to specialty care providers represent a self-selected group of individuals motivated to seek help.

It was reasoned that residents would learn needed skills best by seeing psychiatric problems in a setting where the medical and social contexts are less easily lost in a specialty focus. The curriculum committee was adamant in its belief that the proper setting for teaching primary care psychiatry is the primary care ambulatory setting.

Modeling is an important aspect of resident learning.9 Direct observation and extended clinical contact with a physician who champions the importance of behavioral skills could foster similar attitudes among trainees. Additionally, the behavioral champion's participation in the full range of clinical activity in a residency program would tend to increase his or her stature (and that of the behavioral curriculum) in the eyes of the residents. Thus empowered by the demonstration of broad clinical expertise, such a physician can insist that residents give equal consideration to both behavioral and nonbehavioral skills. Accordingly, the proposed curriculum should be directed and controlled by a family physician with expertise in psychiatry.

Curriculum Development

Following the residency training needs assessment, an 8-week block rotation was designed. Initially offered as 2 contiguous months during the intern year of training, the rotation has been restructured as 2 separate 1-month rotations for first- and second-year residents. Components of the first-year rotation include community medicine and practice management, as well as continuity patient care. The second-year rotation includes specialized training regarding alcohol and drug issues. However, a central activity of each rotation month is participation in an MDC.

The didactic portion of the new curriculum emphasized the standard and familiar clinical process as fully applicable to the area of primary care psychiatry. Four-hour teaching sessions focused on recognition and screening, comorbidity, diagnostic formulation and the application of diagnostic guidelines, therapeutic alliance, selection of treatment strategies, and management of treatment. Brief dynamic psychotherapy was covered in 3 small group discussions, each lasting 2 hours.

The following were made particular areas of emphasis.

Comorbidity of medical and psychiatric illnesses is the rule, not the exception.10 Important areas to consider include medical illnesses and/or treatments and coexisting psychiatric disorders that are associated with related negative health behaviors.

Multiple psychiatric comorbidity is also common. Depression often coexists with anxiety disorders and other psychopathology. Depression itself is not a monolithic acute disorder, but a chronic heterogeneous illness,11,12 waxing and waning in severity with relatively few remissions into an asymptomatic state.13 In particular, subtle manifestations of bipolar illness are more common than previously realized and are often poorly recognized.14 This so-called “soft” bipolar spectrum of illness requires more sophisticated psychopharmacologic management than is generally addressed in family practice training.15

Psychosocial context typically has both cause and effect implications for psychiatric issues.1 For instance, difficulties with employment or interpersonal relationships can be the result of mood impairments or be the source of emotional stressors that trigger or exacerbate psychiatric illness.

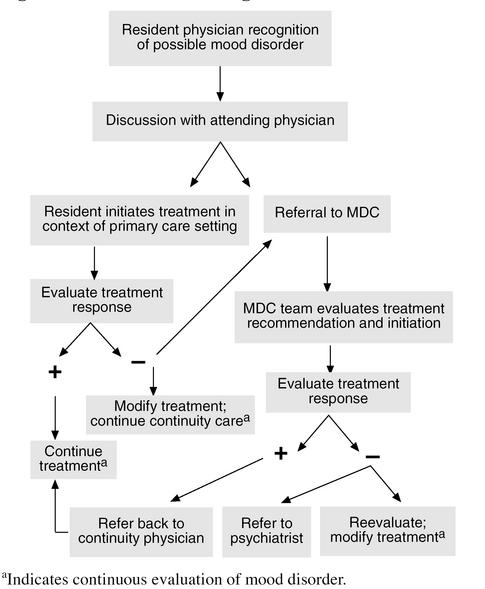

The MDC accepts consultation requests from resident and faculty physicians whose depressed and/or anxious continuity patients are diagnostic dilemmas, refractory to treatment, or in need of more intensive interventions. No outside referrals are accepted. Members of the treatment team include a faculty family physician, a licensed clinical social worker, and a rotating resident or student. Residents, as participant-observers, conduct initial and follow-up interviews in the presence of the 2 faculty members and participate in diagnostic assessment and treatment planning (Figure 1). Debriefing provides a discussion of the initial clinic presentation, comorbidities, and contexts. A 5-axis DSM-IV diagnosis and a treatment plan are formulated.

Figure 1.

Behavioral Health Algorithm

The referring physician receives verbal and written feedback about the consultation. This affords a teachable moment for the referring resident or faculty member. The continuity physician may continue to direct the mental health care based on the team's recommendation or allow the MDC to assume primary care of the problem. Where necessary, patients are referred directly from the MDC to specialty care.

Establishment of Training Sites

The initial clinical training site was an inner-city health clinic staffed by nurse practitioners. Subsequent clinical sites included a rural primary care center (a satellite office of the residency program) and the primary ambulatory care center of the residency training program, located in an urban setting.

Evaluation Methods

Process evaluation.

The educational goal was to develop a comprehensive psychiatric training program for first- and second-year family medicine residents. The administrative goal was to develop a program versatile enough to be implemented in a variety of settings acceptable to the staff with minimal disruption to existing patient care routines. The clinical goal was a patient volume large enough and sufficiently varied to allow for adequate teaching. The comprehensiveness of the curriculum was ensured by including all pertinent mood disorders listed in the DSM-IV in the didactic portion of the behavioral curriculum. Clinical comprehensiveness was measured by evaluating the range and number of mood disorders encountered by each resident in the clinical rotations. Associated psychosocial issues were evaluated in the rural and urban primary care settings by means of a self-report questionnaire.

Outcome evaluation.

Resident identification rates of mood disorders during routine patient care activity before and after the training experience were compared. The pretest measure was resident mood disorder identification rate 1 month prior to the mood disorder curriculum experience. Posttest measures included mood disorder identification rates 1 month and 3 months subsequent to the first month of the curriculum. These measures were accomplished through chart reviews by the MDC faculty.

RESULTS

Process Evaluation

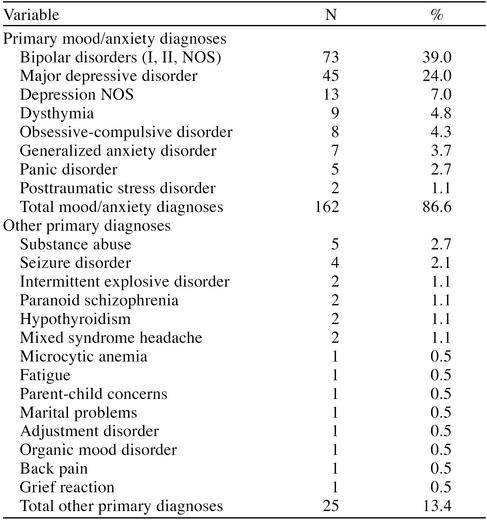

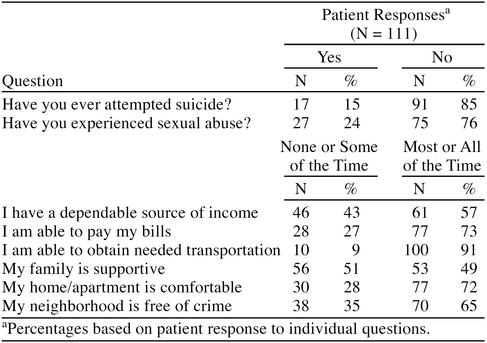

To date, 187 adult patients have been seen at 3 sites during a 60-month period. Of the 22 distinct primary diagnoses identified, the most common was bipolar disorder (39%), followed by major depression (24%) (Table 1). More than half of the patients (57%) had an identified comorbid psychiatric diagnosis that needed to be addressed as part of their treatment. Associated psychosocial issues included financial problems, unemployment, family support issues, and housing concerns (Table 2). A larger-than-expected number of individuals also reported histories of attempted suicide (15%) and sexual abuse (24%) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Mood Disorder Clinic Primary Diagnoses Among 187 Patients

Table 2.

Psychosocial Issues

Outcome Evaluation

Fifty-one residents rotated through 1 or more of 3 practice sites during a 60-month period. Fourteen family medicine residents rotated 1 or 2 months at the inner-city health clinic. In addition to providing patient care, the treatment team made themselves available to explain to the nursing staff how diagnoses were made and how treatment plans were determined. Involvement at this location was terminated after 18 months because of policy decisions unrelated to the consultation service. The curriculum was found to meet Residency Review Committee guidelines during a subsequent accreditation survey.

Twenty-eight residents have completed a clinical rotation at the rural primary care center during the 33 months since the service began there. Twenty-five residents have also rotated through the consultation clinic at the urban primary care center, which has been operating for 35 months. A number of residents who have completed both months of the rotation have had exposure to more than one of these clinical sites. Two residents nearing completion of their training when these programs were implemented chose to use an elective month to participate in this program. One of those individuals is now the faculty member responsible for the consultation service at the urban primary care center.

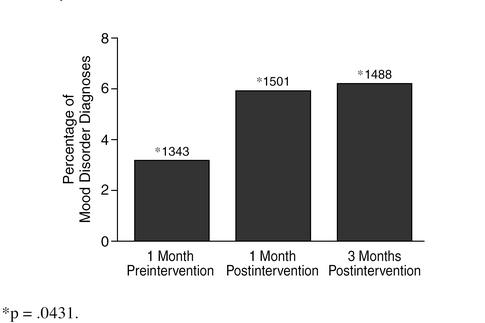

Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the difference in rate of mood disorder recognition by resident physicians before and after training was significant (p ≤ .05). Evaluation of mean recognition rates suggests a continuing positive trend extending at least 3 months posttraining (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Training Effect on Mood Disorder Recognition Rates by Chart Review

Written and verbal feedback pertaining to the curriculum was obtained and evaluated by the MDC faculty. These evaluations, overwhelmingly positive, were used to make adjustments in the logistics of program implementation, content of the didactic sessions, and so on.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to develop an educational program designed to provide focused training for family medicine residents in outpatient recognition and treatment of mood disorders. Data regarding the number of patients seen, the scope of services provided, and training effectiveness suggest that this goal is being met.

Now that the training program has operated in 3 sites, the educational utility of this curriculum and treatment format has been found adaptable to urban and rural settings, to residency training programs and independent clinical settings, and to large established family practice centers, as well as smaller rural satellite residency training centers. The versatility of the mood disorder curriculum is also evident in the scope of training provided. The nurses at the health clinic provided little, if any, psychiatric treatment prior to referral to the consultation service, allowing the referral team to initiate treatment. Resident physicians participating in the MDC at the urban primary care center typically saw patients only after treatment initiated by the continuity physician had been found to be ineffective or problematic. Initially, residents at the rural family practice center referred patients who had even mild levels of distress. This may have been due to the fact that the rural satellite was staffed with several residents who were retraining in family practice from surgical subspecialties (urology, general surgery, obstetrics/gynecology). Over time, a change in referral patterns was noticed. Although the consultation team continues to be asked for advice regarding initiating psychiatric treatment, it is becoming less common for patients to meet with the team unless initial treatment efforts on the part of the primary care provider have been unsuccessful, there is a diagnostic dilemma, or there is an immediate need for intensive intervention. The residents may be more proficient at managing treatment themselves or more comfortable in initiating treatments with the knowledge that consultation is readily available.

After some experimentation, these site-specific differences proved to be an advantage during the training process. First-year residents are now assigned to the rural primary care center for their initial MDC experience. In this way, they are better able to evaluate patients from the beginning of the treatment process. Residents who have completed this basic level of training in the rural setting are then placed with faculty in the urban center to evaluate more complicated presentations and treatments.

Patients referred to these mood disorder programs reflected the heterogeneity of individuals suffering from mood disorders. They provided a rich educational resource, presenting with a wide range of illness subtypes and confounding psychosocial issues, and as a result, a broad spectrum of treatment strategies. This program encouraged awareness and recognition of patient disorders that otherwise might have been overlooked or treated less effectively. The prevalence, variety, and range of illness presentations justify the need for an ongoing educational program dedicated to evaluating and treating mood disorders.

The Axis I diagnoses encountered validated the structure and content of the didactic curriculum, particularly with regard to the frequency of bipolar spectrum illnesses. Thirty-nine percent of adult patients seen were bipolar, regardless of Axis II (personality) or Axis IV (psychosocial) contexts (DSM-IV). Previous cross-sectional, instrument-based investigations of the depressive subtypes in primary care have not found this level of bipolar illness. However, cross-sectional evaluations with instruments insensitive for hypomania will not accurately assess this issue. Our finding of a high level of bipolar illness in this sample is consistent with a longitudinal descriptive study and emerging literature in the area.14,15 Even if one focuses on the MDC as a referral center, the fact remains that levels of recognition and diagnosis for mental illness in primary care are low. Therefore, those patients referred to the MDC (often on recognition of distress only) may represent a more general sample of what actually exists in primary care. If the MDC data reflect this, it reinforces the need for emphasizing this area of mood disorders in continuing medical education for family physicians.

Residents gained experience with a broad variety of medications used to treat depression and anxiety, including most antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and the mood stabilizers lithium and valproate. Resident physicians became familiar with medication side effects, intolerance, and both stable and unstable nonresponse patterns during the treatment process. This enabled them to acquire experience in managing common medication side effects and overcoming nonresponse by either switching antidepressants or augmenting antidepressants with other medications. Lithium was used in primary and augmentation roles with excellent tolerance and response.

The psychosocial content of the training program builds upon both systems and developmental theory. Although the majority of patients did not endorse financial or housing concerns as being a significant problem (see Table 2), those who did provided ample opportunity for education related to evaluation and coordination of local community resources. Information on stages and transitional periods in the life cycle was useful for evaluating individual and familial strengths and weaknesses. The therapeutic framework for instruction in psychotherapy was based on Stuart and Lieberman's The Fifteen Minute Hour,16 which outlines the skills for providing time-limited, problem-focused psychotherapy.

The positive impact of using an interdisciplinary approach is consistent with previous studies.17,18 Many individuals suffering from depression or anxiety also face significant psychosocial obstacles. Appropriate care requires addressing environmental and emotional needs in addition to biological underpinnings. Thus, mental health professionals are an integral part of the clinical team throughout the treatment process. Residents trained in the MDC heard a variety of points of view and learned to value them all.

Program implementation required addressing a number of specific issues. The first was administrative support for focused resident training in the area of mood disorders. Program administrators were receptive to the idea of developing a structured and intensive training experience in this area. Also, apart from expenditures related to personnel, initiating this program required little capital investment. Space requirements were minimal, and accommodations were made in a variety of settings ranging from small examination rooms to large reception areas. Scheduling and logistical problems were easily addressed once the necessary administrative support was obtained.

The scheduling rate for patients wanting appointments is now routinely over capacity. As referrals increased, the number of patients requiring assessments and psychotherapies outside of the MDC led to expansion of the original concept. The social worker began scheduling separate appointments to provide these additional services.

Feedback relating to the MDC is overwhelmingly positive, and residents readily acknowledge improvement in both skill and comfort level when dealing with psychiatric issues following this rotation. Objective evaluation of practice patterns before and after the training period lends additional support to the educational effectiveness of this program. It is encouraging to note that improvements seen during the month immediately following training continue to be evident even after 3 months (see Figure 2). These increasing recognition rates may in part be due to the continuous role modeling of faculty physicians with the program. The training effect may also have been due to other issues, such as advancement in training year or educational experiences in other areas. This is a pilot study focusing on content, implementation, and adaptability. More rigorous investigations of the training effect are anticipated.

The long-term goal is to see mood disorder consultation services existing on-site in additional family practice settings, perhaps in an integrated behavioral-medical model of care. In these arrangements, experienced family physicians would direct multidisciplinary groups. Mental health professionals associated with the group would charge fee-for-service or provide services as negotiated within the context of capitation contracts with managed care organizations. As the cost of providing this care is transferred from the insurance carrier to the primary care provider, the need for third-party mental health reviewers would be reduced. Outside psychiatric consultation would still be required for the most complex or refractory cases and for non–mood illnesses such as schizophrenia, mental retardation, dementias, and others.

The experience presented here further suggests the potential value of developing a lifestyle enhancement or “life skills” curriculum for patients. Based on the situations encountered, patient education dealing with personal finance, legal affairs, governmental agencies, and interpersonal relationships would be useful additions to comprehensive treatment planning.

Psychiatric care is one of several areas where managed care organizations will encourage family physicians to expand their scope of practice. This article describes one approach for training resident physicians to appropriately recognize, effectively treat, and efficiently manage individuals affected by the wide variety of mood disorders commonly seen by primary care physicians.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sheila M. Thomas, M.D., Shari K. Lee, L.C.S.W., and Patricia D. Cunningham, M.S.N., Psych.F.N.P., for their participation in the implementation and evaluation of the project and manuscript.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Coryell W, Endicott J, Keller MB. Predictors of relapse into major depressive disorder in a non-clinical population. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1353–1358. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.10.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Distressed high utilizers of medical care: DSM-III-R diagnoses and treatment needs. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1990;12:355–362. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(90)90002-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier DS, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. JAMA. 1990;264:2511–2518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm R, Wells K. How can care for depression become more cost-effective? JAMA. 1995;273:51–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block M, Schulberg HC, Coulehan JC, et al. Diagnosing depression among new patients in ambulatory training settings. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1988;1:91–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormel J, Koeter MWJ, van den Brink W, et al. Recognition, management, and course of anxiety and depression in general practice. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:700–706. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810320024004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper W, Kyker KA, Rodney WM. Colonoscopy by a family physician: a nine-year experience of 1048 procedures. J Fam Pract. 1996;43:561–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrights S. Examining what residents look for in their role models. Acad Med. 1996;71:290–292. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199603000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, McGonagle K, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiskal HS, Mallya G. Criteria for the “soft” bipolar spectrum: treatment implications. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1987;23:68–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassano G, Akiskal HS, Savino M, et al. Proposed subtypes of bipolar II and related disorders: with hypomanic episodes (or cyclothymia) and with hyperthymic temperament. J Affect Disord. 1992;26:127–140. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(92)90044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormel J, Oldehinkel T, Brilman E, et al. Outcome of depression and anxiety in primary care: a three-wave 3½-year study of psychopathology and disability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:759–766. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820220009001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning JS, Haykal RF, Connor PD, et al. On the nature of depressive and anxious states in a family practice setting: the high prevalence of bipolar II and related disorders in a cohort followed longitudinally. Compr Psychiatry. 1997;38:102–108. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(97)90089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning JS, Connor PD, Sahai A. The bipolar spectrum: a review of current concepts and implications for depression management in primary care. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7:63–71. doi: 10.1001/archfami.7.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart M, Lieberman J. The Fifteen Minute Hour: Applied Psychotherapy for the Primary Care Physician. New York, NY: Praeger. 1986 [Google Scholar]

- Alt-White A. An interdisciplinary approach to improving the quality of life for nursing home residents. Nurs Connections. 1993;6:51–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson B, Perkins M. Interdisciplinary team approach in the rehabilitation of hip and knee arthroplasties. Am J Occup Ther. 1994;48:439–445. doi: 10.5014/ajot.48.5.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]