Abstract

The curative treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), including surgical resection and radiofrequency ablation (RFA), do not prevent tumour recurrence effectively. Dendritic cell (DC)-based immunotherapies are believed to contribute to the eradication of the residual and recurrent tumour cells. The current study was designed to assess the safety and bioactivity of DC infusion into tumour tissues following transcatheter hepatic arterial embolization (TAE) for patients with cirrhosis and HCC. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were differentiated into phenotypically confirmed DCs. Ten patients were administered autologous DCs through an arterial catheter during TAE treatment. Shortly thereafter, some HCC nodules were treated additionally to achieve the curative local therapeutic effects. There was no clinical or serological evidence of adverse events, including hepatic failure or autoimmune responses in any patients, in addition to those due to TAE. Following the infusion of 111Indium-labelled DCs, DCs were detectable inside and around the HCC nodules for up to 17 days, and were associated with lymphocyte and monocyte infiltration. Interestingly, T lymphocyte responses were induced against peptides derived from the tumour antigens, Her-2/neu, MRP3, hTERT and AFP, 4 weeks after the infusion in some patients. The cumulative survival rates were not significantly changed by this strategy. These results demonstrate that transcatheter arterial DC infusion into tumour tissues following TAE treatment is feasible and safe for patients with cirrhosis and HCC. Furthermore, the antigen-non-specific, immature DC infusion may induce immune responses to unprimed tumour antigens, providing a plausible strategy to enhance tumour immunity.

Keywords: clinical safety, dendritic cells, hepatocellular carcinoma, immunotherapy, transcatheter hepatic arterial embolization

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) occurs primarily in individuals with cirrhosis related to either hepatitis C virus (HCV) or hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections [1–3]. The curative treatments for HCC, including surgical resection and percutaneous radiofrequency ablation (RFA), do not prevent tumour recurrence efficiently because active hepatitis and cirrhosis in the surrounding nontumour liver tissues exhibit high carcinogenetic potentials to develop de novo HCC [4–7]. In addition, their reduced hepatic reserve due to cirrhosis decreases the tolerance to these local treatments and reduces drug metabolism, including that of anti-cancer agents, and therefore limits their usefulness. Among many novel strategies targeting HCC recurrence, immune-based therapies are believed to enhance the sensitivity, specificity and self-regulation of the immune system to find and eradicate tumour cells wherever they reside [8].

Dendritic cells (DCs) are the most potent type of antigen-presenting cells in the human body, and are involved in the regulation of both innate and adaptive immune responses [9–11]. During DC development, immature DCs exhibit the unique ability to take up and process antigens in the peripheral blood and tissues [12,13]. Subsequently, they migrate to draining lymph nodes, where they must mature to fully activated DCs to present the antigens to resting lymphocytes and elicit T cell responses [14–16]. During the maturation processes, they express high levels of cell-surface major histocompatibility complex (MHC) antigen complexes and co-stimulatory molecules [17]. So far, most of the DC-based immunotherapies have been performed using intravenous (i.v.), intradermal (i.d.) and subcutaneous (s.c.) routes and lymph node injection following the predictive tumour antigen stimulation ex vivo [18,19]. Yet the clinical efficacy remained controversial because consistent tumour destruction or extended life span has not been observed in most treated cancer patients [20–22]. Accordingly, antigen stimulation may not be suitable for cancer treatments, or the proper tumour antigens may not be present to be taken up by DCs after the infusion.

In addition, DCs are reported to induce immune responses to target antigens by a cross-priming mechanism that is greatly enhanced when the target cells are apoptotic [23,24]. Apoptosis of tumour cells is induced by the standard treatments for HCC, i.e. transcatheter hepatic arterial embolization (TAE), percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI), RFA and intra-arterial chemotherapy [25,26]. Importantly, we have observed recently that immune responses specific for tumour antigens and peptides were enhanced during the course of the therapies, while anti-tumour responses were not enough to prevent HCC recurrence [27].

Based on these observations, we suggested a novel DC-based therapy in which immature DCs were injected through an arterial catheter into apoptotic tumour tissues following TAE. Immature DCs were delivered to HCC tumour tissues, by which we hypothesized that the physiological maturation steps including antigen ingestion, migration and presentation might proceed within the patient's body. In the current study, clinical safety was evaluated in patients with HCV-related cirrhosis complicated with HCC. The results suggest that immature DCs were infused successfully and safely to tumour tissues, and immune responses were induced to the tumour antigen peptides with human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-A24 binding motif, which are shared by most Asian individuals.

Patients and methods

Patients

Inclusion criteria were a radiological diagnosis of primary HCC by CT angiography, HCV-related HCC, a Karnofsky score of ≥ 70%, an age of ≥ 20 years, informed consent, the following normal baseline haematological parameters (within 1 week before DC administration): haemoglobin ≥ 8·5 g/dl; white cell count ≥ 2000/ml; platelet count ≥ 50 000/ml; creatinine < 1·5 mg/dl, and liver damage A or B [28].

Exclusion criteria included severe cardiac, renal, pulmonary, haematological or other systemic disease associated with a discontinuation risk; human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection; prior history of other malignancies; history of surgery, chemotherapy or radiation therapy within 4 weeks; immunological disorders including splenectomy and radiation to the spleen; corticosteroid or anti-histamine therapy; current lactation; pregnancy; history of organ transplantation; or difficulty in follow-up.

There were 10 patients enrolled in the study (one woman and nine men), with an age range of 45–79 years (Table 1). Patients with verified radiological diagnoses of HCC stage II or more were eligible and enrolled in this study. Similarly, a group of 11 patients treated with TAE without DC administration was also enrolled in this study as a control. The Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved the study protocol. This study complied with ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Adverse events were monitored for 1 month after the DC infusion in terms of fever, vomiting, abdominal pain, encephalopathy, myalgia, ascites, gastrointestinal disorder, bleeding, hepatic abscess and autoimmune diseases.

Table 1.

Patient characteristcs and treatments.

| Patient no. | Gender | Age (years) | HLA | TNM stages | No. of tumours | Largest tumour (mm) | Child-Pugh | KPS | Post-TAE Rx | Image complete Rx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 45 | A2 A11 | IVB | Multiple | 50 | A | 100 | No | Complete |

| 2 | M | 60 | A26 A33 | II | 3 | 15 | A | 100 | RFA | Incomplete |

| 3 | F | 70 | A3 A24 | II | 2 | 15 | A | 100 | RFA | Complete |

| 4 | M | 77 | A2 A24 | II | 3 | 10 | A | 100 | RFA | Complete |

| 5 | M | 73 | A24 | III | Multiple | 70 | B | 80 | Chemo | Incomplete |

| 6 | M | 62 | A24 A26 | III | Multiple | 32 | A | 100 | RFA | Complete |

| 7 | M | 67 | A11 A24 | III | Multiple | 35 | A | 100 | Chemo | Incomplete |

| 8 | M | 60 | A2 A24 | II | 2 | 40 | B | 100 | MCT | Complete |

| 9 | M | 79 | A2 A33 | III | 5 | 60 | A | 100 | RFA | Complete |

| 10 | M | 76 | A11 A24 | II | 1 | 45 | A | 100 | Ope | Complete |

| 11 | M | 71 | n.d. | II | 1 | 35 | B | 100 | No | Complete |

| 12 | M | 68 | A24 | II | 4 | 20 | A | 100 | RFA | Complete |

| 13 | F | 66 | A2 A24 | IVA | 3 | 30 | A | 100 | No | Complete |

| 14 | F | 68 | A11 A33 | IVA | Multiple | 50 | B | 100 | Chemo | Incomplete |

| 15 | F | 74 | n.d. | II | 2 | 20 | B | 100 | RFA | Complete |

| 16 | F | 67 | A2 A24 | III | 3 | 25 | A | 100 | RFA | Incomplete |

| 17 | F | 70 | A2 A11 | I | 1 | 20 | B | 100 | No | Complete |

| 18 | M | 59 | n.d. | II | 3 | 20 | A | 100 | RFA | Complete |

| 19 | M | 68 | n.d. | III | Multiple | 25 | B | 100 | RFA | Complete |

| 20 | M | 70 | A2 A26 | II | 5 | 15 | B | 100 | No | Complete |

| 21 | M | 80 | A2 A24 | III | 3 | 38 | B | 100 | No | Complete |

Chemo: chemotherapy; Child-Pugh: Child-Pugh classification; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; KPS: Karnovsky performance scores; n.d.: not determined; Ope: partial hepatectomy; RFS: percutaneous radiofrequency ablation; Rx: treatment; TAE: transcatheter arterial embolization; TNM: tumour-node metastasis.

Preparation and injection of autologous DCs

DCs were generated from blood monocyte precursors as reported previously [29,30]. Briefly, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by centrifugation in Lymphoprep™ Tubes (Nycomed, Roskilde, Denmark). For generating DCs, PBMCs were plated in six-well tissue culture dishes (Costar, Cambridge, MA, USA) at 1·4 × 107 cells in 2-ml per well and allowed to adhere to plastic for 2 h. Adherent cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 1% heat-inactivated autologous plasma, 100 U/ml penicillin G (GMP grade; Meiji, Tokyo, Japan), 100 µg/ml streptomycin sulphate (GMP grade; Meiji), 1000 U/ml recombinant human interleukin (IL)-4 (GMP grade; Cell Genix, Freiburg, Germany) and 100 ng/ml recombinant human granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (GMP grade; Novartis, Basel, Switzerland) for 7 days. In the selected cases, the cells were pulsed with 10 µg/ml keyhole limpet haemocyanin (KLH) [depyrogenated, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) free; Calbiochem-Novabiochem Corp., San Diego, CA, USA] overnight 1 day before injection. On day 7, the cells were harvested for injection, 5 × 106 cells were reconstituted in 5 ml normal saline containing 1% autologous plasma, mixed with absorbable gelatin sponge (Gelfoam; Pharmacia & Upjohn, Peapack, NJ, USA) and infused through an arterial catheter following Lipiodol (iodized oil) (Lipiodol Ultrafluide, Laboratoire Guerbet, Aulnay-Sous-Bois, France) injection during selective TAE therapy. Release criteria for DCs were viability > 80%, purity > 30%, negative Gram stain and endotoxin polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and negative in process cultures from samples sent 48 h before release. All products met all release criteria, and the DCs had a typical phenotype of CD14– and HLA-DR+.

Flow cytometry analysis

The DC preparation was assessed by staining with the following monoclonal antibodies (MoAb) for 30 min on ice: anti-CD14-allophycocyanin (APC) (MÖP9), anti-HLA-DR-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (L243), anti-CD11c-APC (S-HCL-3), anti-CD123-phycoerythrin (PE) (9F5) (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA, USA), anti-CD80-PE (MAB104), anti-CD83-PE (HB15a) and anti-CD86-PE (HA5·2B7) (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA). Cells were analysed on a FACSCalibur™ flow cytometer. Data analysis was performed with CELLQuest™ software (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA).

111Indium oxinate labeling and autoradiography

DCs were labelled with 111Indium (In) oxinate at a specific activity of 32·5 µCi/106 cells according to the protocols supplied by the manufacturer (Nihon Medi-Physics, Hyogo, Japan). Scintigraphic images of the depot were acquired with a gamma camera 6, 24, 48 h and 7 days after injection. In one case, the treated HCC nodule was accidentally resected surgically 17 days after DC infusion. Autoradiography was conducted and analysed on a BAS 1000 image analyser (Fuji Photo Film, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunohistochemical analysis

The liver tissues were fixed in buffered zinc formalin (Anatech Ltd, Battle Creek, MI, USA), embedded in paraffin, sectioned (at 3 µm), and stained with haematoxylin and eosin. The paraffin sections were deparaffinized, treated in a pressure cooker for 1–40 min, and incubated with mouse anti-human CD1a (MTB1; 1 : 20 diluted), CD4 (1F6; 1 : 20), CD8 (1A5; 1 : 20), CD20 (7D1; 1 : 100), CD56 (CD564; 1 : 50), CD83 (1H4b; 1 : 20) (Novocastra, Newcastle, UK), CD14 (7; 1 : 20) or HLA-DR (LN3; 1 : 100) (LabVision, Fremont, CA, USA) antibody overnight at 4°C. The cells were then visualized using a Vectastain ABC Standard Kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), and the tissue sections were counterstained with haematoxylin before mounting.

Interferon (IFN)-γ enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay

The prevalence of activated, tumour antigen peptide-specific PBMCs was determined by IFN-γ ELISPOT analysis (Mabtech, Nacka, Sweden). Briefly, 96-well mixed cellulose ester membrane-backed plates (MAHA S4510; Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) were coated with 100 µl of an anti-IFN-γ MoAb 1-D1K (15 µg/ml; Mabtech) overnight at 4°C. Peptides were added directly to the wells at a final concentration of 10 µg/ml. PBMCs were added to the wells at 3 × 105 cells/well. The plates were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 overnight (14–16 h) and then processed as described [31,32]. ELISPOT assays were conducted in duplicate wells. IFN-γ producing cells were counted by direct visualization and are expressed as mean number of spots per 3 × 105 cells. The number of specific spots was determined by subtracting the number of spots in the absence of antigen. Responses were considered positive if more than 10 specific spots were detected and if the number of spots in the presence of antigen was at least twofold greater than the number of spots in the absence of antigen. The negative controls consisted of incubation of PBMCs with a peptide representing an HLA-A24 restricted epitope derived from HIV envelope protein (HIVenv584) [33] and were always < five spots per 3 × 105 cells. The positive controls consisted of 10 ng/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 500 ng/ml ionomycin (Sigma) or a cytomegalovirus (CMV) pp65-derived peptide (CMVpp65328) [34].

HLA-A24 restricted peptide epitopes used in this study, AFP403 (KYIQESQAL), AFP424 (EYYLQNAFL), AFP434 (AYTKKAPQL), AFP357 (EYSRRHPQL) [27], hTERT1088 (TYVPLLGSL), hTERT845 (CYGDMENKL), hTERT167 (AYQVCGPPL) (unpublished), hTERT461 (VYGFVRACL), hTERT324 (VYAETKHFL) [35], Her-2/neu8 (RWGLLLALL) [36], MRP3765 (VYSDADIFL) and MRP3692 (AYVPQQAWI) [37], were synthesized at Mimotope (Melbourne, Australia) and Sumitomo Pharmaceuticals (Osaka, Japan). They were identified using mass spectrometry, and their purities were determined to be > 80% by analytical high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Regarding the immunological properties of the epitopes in HCC patients, we found that AFP- and hTERT-derived epitopes were recognized by cytotoxic T lymphocytes in 7·9–21·1% and 6·9–12·5% of 38 and 72 patients, respectively [27,38]. On the other hand, immune responses to Her-2/neu- and MRP3-derived epitopes have not been reported; however, overexpression of Her-2/neu protein was reported to be 2·42% in HCC patients [39], and in our unpublished data the immune responses to Her-2/neu-derived epitope were observed in 5·1% HCC patients (tested 38 patients). In addition, expression of MRP3 protein was reported to be 100% in HCC patients [40]. In our unpublished data, the immune responses to MRP3-derived epitope were observed in 20·5–25·6% HCC patients (38 tested patients).

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± s.d. Differences between groups were analysed for statistical significance by the Mann–Whittney U-test. The estimated probability of tumour recurrence-free survival was determined using the Kaplan–Meier method. The Mantel–Cox log-rank test was used to compare curves between groups. Any P-values less than 0·05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Isolation and characterization of DCs

Adherent cells isolated from PBMCs were differentiated into DCs in the presence of IL-4 and granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). DCs from each study patient were shown to develop high levels of MHC class II (HLA-DR) and co-stimulatory molecule B7-2 (CD86) and showed the absence of markers for mature monocytes (CD14). In addition, DCs obtained were phenotypically immature (CD80lowCD83low) and classified to myeloid (CD11c+ CD123–) and plasmacytoid (CD11c–CD123+) subsets (Table 2). Furthermore, sufficient numbers (at least 1 × 107) of functional DCs were isolated from 200 ml of peripheral blood in all patients in this clinical trial.

Table 2.

Properties of infused dendritic cells.

| lin- HLA-DR+ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient no. | %CD14- HLA-DR+ | %CD11c+ CD123- | %CD11c- CD123+ | %CD80+ | %CD83+ | %CD86+ |

| 1 | 34·5 | 5·8 | 8·4 | 1·6 | 1·9 | 11·5 |

| 2 | 56·2 | 49·7 | 39·3 | 4·1 | 3·2 | 92·4 |

| 3 | 35·6 | 63·6 | 6·1 | 0 | 5·7 | 96·0 |

| 4 | 32·7 | 22·6 | 56·5 | 1·9 | 1·2 | 61·6 |

| 5 | 40·4 | 24·3 | 57·3 | 34·9 | 27·7 | 94·4 |

| 6 | 60·4 | 35·8 | 47·0 | 11·4 | 1·5 | 84·4 |

| 7 | 46·4 | 54·7 | 10·7 | 12·9 | 12·5 | 83·2 |

| 8 | 62·8 | 7·6 | 32·3 | 19·0 | 20·5 | 49·1 |

| 9 | 55·2 | 35·2 | 35·5 | 28·8 | 18·3 | 73·0 |

| 10 | 34·0 | 9·5 | 7·0 | 12·1 | 8·4 | 31·8 |

| Mean | 45·8 | 30·9 | 30·0 | 12·7 | 10·1 | 67·7 |

| s.d. | 11·9 | 20·5 | 20·5 | 11·9 | 9·3 | 28·9 |

Safety of autologous DC administration

DC administration was performed during TAE therapy, in which DCs were mixed together with Gelfoam and infused through an arterial catheter following Lipiodol injection. Adverse events were monitored clinically and biochemically after DC infusion (Table 3). There were no grades III or IV National Cancer Institute common toxicity criteria adverse events associated with DC infusion and TAE in this study. Furthermore, the adverse events of the patients treated with DC infusion and TAE were compared with the control patients treated with TAE alone in terms of fever, vomiting, abdominal pain, encephalopathy, myalgia, ascites, gastrointestinal disorders, bleeding, hepatic abscess and autoimmune diseases. Although the clinical courses of five of the patients infused with DCs were complicated with high fever, there were no significant differences in the frequency or severity of adverse events associated with DC infusion. There was also no clinical or serological evidence of hepatic failure or autoimmune response in any patients. Thus, the current treatment of DC infusion was performed safely at the same time as TAE in patients with cirrhosis and HCC.

Table 3.

General clinical outcome.

| Adverse events | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient no. | Fever (days) | Vomiting | Abdominal pain | Encephalopathy | Others | DTH to KLH | Tumour recurrence | Survival w/o HCC (months) | Survival (months) | Death/alive |

| 1 | 1 | No | No | No | No | n.d. | Yes | 6 | 17 | Death |

| 2 | 2 | No | No | No | No | n.d. | Yes | 13 | 17 | Alive |

| 3 | No | No | No | No | No | n.d. | Yes | 8 | 30 | Alive |

| 4 | 4 | Yes | No | No | No | n.d. | Yes | 11 | 36 | Alive |

| 5 | No | No | No | No | No | n.d. | n.d. | 2 | 2 | Death |

| 6 | No | No | No | No | No | n.d. | Yes | 5 | 34 | Alive |

| 7 | 8 | No | No | No | No | n.d. | Yes | 14 | 22 | Death |

| 8 | No | No | No | No | No | Positive | No | 9 | 9 | Death |

| 9 | 5 | Yes | No | No | No | n.d. | Yes | 6 | 30 | Alive |

| 10 | No | No | No | No | No | Positive | Yes | 22 | 24 | Alive |

| Mean | 9·6 | 22·1 | ||||||||

| s.d. | 5·7 | 11·0 | ||||||||

| 11 | No | No | No | No | No | n.d. | Yes | 4 | 6 | Death |

| 12 | No | No | No | No | No | n.d. | Yes | 9 | 24 | Death |

| 13 | No | No | Yes | No | No | n.d. | Yes | 2 | 8 | Alive |

| 14 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | n.d. | Yes | 3 | 9 | Death |

| 15 | 3 | No | No | No | No | n.d. | Yes | 18 | 20 | Death |

| 16 | 1 | No | No | No | No | n.d. | Yes | 8 | 36 | Alive |

| 17 | No | No | No | No | No | n.d. | Yes | 6 | 12 | Death |

| 18 | No | No | No | No | No | n.d. | Yes | 11 | 36 | Alive |

| 19 | 5 | No | Yes | Yes | No | n.d. | Yes | 7 | 30 | Alive |

| 20 | No | No | No | No | No | n.d. | Yes | 5 | 11 | Death |

| 21 | No | No | No | No | No | n.d.. | n.d. | 4 | 4 | Alive |

| Mean | 7·0 | 17·8 | ||||||||

| s.d. | 4·5 | 12·0 | ||||||||

Adverse events/others: myalgia, gastrointestinal disorder, bleeding, hepatic abcess and autoimmune diseases; DTH: delayed-type hypersensitivity skin test; KLH: keyhole limpet haemocyanin; n.d.: not determined.

Kinetics and in situ effects of DCs following infusion into HCC tissues

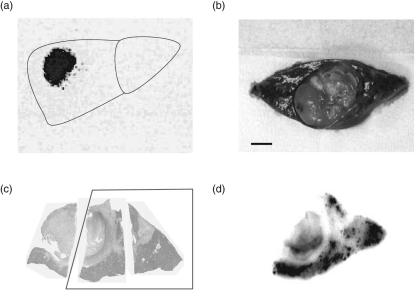

DCs were labelled with 111In-oxine and infused into tumour tissues through an arterial catheter following TAE in two patients (numbers 9 and 10). The kinetics of 111In-labelled DCs were monitored by a gamma camera after the infusion (Fig. 1a). Radioactivity at the tumour site decreased after the infusion, but was still detectable up to 14 days after the infusion, indicating that the DCs stayed alive for more than 2 weeks. However, tracking of labelled DCs to regional lymph nodes was not seen in the current imaging, due possibly to insufficient numbers of migrated DCs, or otherwise due to DC paralysis in tumour tissues [41].

Fig. 1.

Kinetics of autologous dendritic cells (DCs) following infusion into tumour tissues in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). DCs were labelled with 111In-oxine and infused into tumour tissues through an arterial catheter following transcatheter hepatic arterial embolization (TAE). (a) Scintigraphic images of the depot were acquired with a gamma camera 7 days after injection. (b) In one case, the treated HCC nodule was accidentally resected surgically 17 days after DC infusion. Bar represents 1 cm. Resected tissues were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (c) and, using the tissue comparable to the inset in (c), autoradiography was conducted and analysed on an image analyser (d).

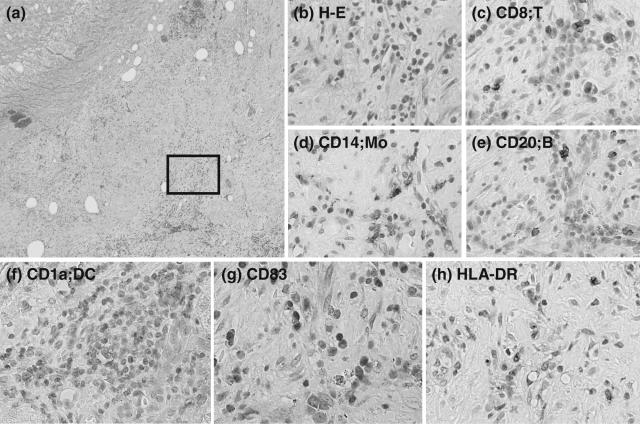

One of the patients (number 10) proceeded unexpectedly to curative surgery 17 days after the DC infusion. The tissue radioactivity was investigated using autoradiography and analysed on an image analyser (Fig. 1b,c,d). Surprisingly, radioactivity was still detectable in the tumour tissue and surrounding liver parenchyma. In addition, immunohistochemistry of the liver tissue was performed using MoAbs specific for cell surface markers CD8, CD14 (monocyte), CD20 (B cell), CD1a (DC) HLA-DR (antigen-presenting cell) and CD83 (DC maturation/activation) (Fig. 2). Immunohistochemical analysis revealed many CD1a-positive DCs in the area surrounding HCC nodules treated with autologous DCs and TAE 17 days previously. In addition, CD83-positive cells and HLA-DR-positive antigen-presenting cells were seen in the same areas of liver tissue. Interestingly, CD83-positive cells were rarely detected in liver tissues of HCC patients, as reported previously [42]. Many CD8+ T cells, CD14+ monocytes and CD20+ B cells were recruited in the same area. In conjunction with the detection ofradioactivity, these data indicate that DCs were viable for more than 17 days following the infusion and seemed to contribute to the recruitment and activation of immune cells.

Fig. 2.

Immunohistochemical analysis of a surgically resected liver tissue containing a nodule of hepatocellular carcinoma in a patient infused with autologous dendritic cells (DCs) 17 days previously, described in the legend to Fig. 1. The liver tissue was stained with haematoxylin and eosin (a and b) and for CD8 (c), CD14 (d), CD20 (e), CD1a (f), CD83 (g) and human leucocyte antigen D-related (HLA-DR) (h). (b) Close-up of the inset in (a). Areas comparable to (b) are indicated in (c–h). Cells were stained positively in brown. Original magnifications, ×40 (a) and ×400 (b–h).

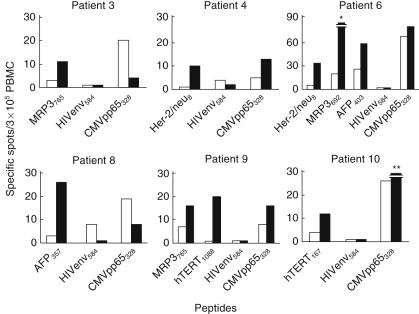

Immune responses induced following DC infusion

To evaluate the immunomodulatory effects of DCs infused into HCC tissues, PBMCs were obtained 4 weeks after the infusion, pulsed with the peptides derived from AFP, hTERT, Her-2/neu and MRP3 and IFN-ã production was quantified by ELISPOT. Interestingly, frequencies of IFN-ã-producing cells in response to stimulation with HLA-A24-restricted peptide epitopes derived from tumour antigens, Her-2/neu, MRP3, hTERT and AFP, were increased 2–20-fold in six of the eight HLA-A24-positive patients after the treatments (Fig. 3). In addition, in two of the cases DCs were stimulated with KLH before the infusion, and the intradermal test was performed 2 weeks later. Both cases displayed a positive reaction (Table 3), indicating that DCs induced cellular immunity successfully following the treatments [43]. Collectively, these results demonstrated that DC infusion induced immune responses to unprimed tumour antigens, suggesting that antigen-non-specific immature DCs in the tumour tissues enhanced tumour immunity in vivo.

Fig. 3.

Immune responses to human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-A24 restricted peptide epitopes derived from tumour antigens in patients infused with dendritic cells (DCs). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained before (open bars) and 4 weeks after the infusion (solid bars), pulsed with the peptides derived from AFP, hTERT, Her-2/neu and MRP3, and interferon (IFN)-ã production was quantified by enzyme-linked immunospot assay (ELISPOT). Negative controls consisted of incubation of PBMC with a peptide representing an HLA-A24 restricted epitope derived from HIV envelope protein (HIVenv584). Positive controls consisted of 10 ng/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and 500 ng/ml ionomycin or a cytomegalovirus (CMV) pp65-derived peptide (CMVpp65328). Responses were considered positive if more than 10 specific spots were detected and if the number of spots in the presence of peptide was at lease twofold greater than the number of spots in the absence of peptide. *230 specific spots; **32 specific spots.

Recurrence-free survival following DC infusion

A further objective of this study was to determine the clinical response to DC infusion. Therefore, we compared recurrence-free survival between patients treated with TAE with (n = 10) and without (n = 11) DC administration (Table 3). While there was a trend for the patients infused with DCs to display longer recurrence-free survival, these differences did not reach statistical significance [mean recurrence-free survival (± s.d.) of patients with and without DC administration: 9·6 ± 5·7 and 7·0 ± 4·5 months, respectively; P = 0·13]. In addition, there was no correlation between infused DC phenotypes characterized by the surface markers (Table 2) and recurrence-free survival after the infusion. Although the strong CD8+ response against MRP3692 was induced in patient 6 (Fig. 3) the clinical outcomes, including recurrence-free survival, were not distinct from the other DC-treated patients.

Discussion

Tumour recurrence rates after curative treatments for HCC are extremely high in patients with active hepatitis and cirrhosis related to HBV and HCV infections [4–6]. Although current treatments, including surgical resection and RFA, displayed almost complete prevention of local recurrence in the cirrhotic liver, the surrounding non-tumour liver tissues exhibited high carcinogenetic potentials to develop de novo HCC. Significant risk factors for recurrence have been reported to be cirrhosis and a higher grade of hepatitis activity [44–46]. IFN therapy and anti-inflammatory drugs have been implicated in the reduction of HCC recurrence [47,48]; however, they did not prevent recurrence satisfactorily. To develop novel therapies targeting HCC recurrence, many immune-based trials have been performed [8].

The current study indicates that immature DC infusion following TAE therapy did not cause additional adverse events in patients with cirrhosis and HCC, and that infused DCs remained alive around the tumour tissues for more than 17 days, as indicated by monitoring the kinetics of 111In-DC, and contributed to the recruitment and activation of immune cells in situ. Immune responses were induced to the tumour antigen peptides with HLA-A24 binding motif. Furthermore, intradermal tests were positive when stimulated with KLH. Ultimately, the patients treated with this DC-based immunotherapy did not display statistically longer recurrence-free survival. This study demonstrated the feasibility, safety and bioactivity of transcatheter arterial DC infusion into tumour tissues for patients with cirrhosis and HCC. The data suggest the ability of an active immunotherapeutic strategy to generate antigen-specific cytotoxicity in HCC patients.

Transcatheter arterial DC infusion into tumour tissues following TAE treatment was feasible and safe for patients with cirrhosis and HCC whose hepatic reserve was decreased, similar to reports from other DC immunotherapy trials [20–22]. Mild toxicity included more patients with fever compared to TAE treatment alone, while their durations were comparable. Two patients complained of infrequent vomiting. To date, no clinical or radiological features of autoimmune diseases have been detected in the current study, nor have other DC immunotherapy trials reported any significant autoimmune events [20–22].

111In-labelled DCs were detectable inside and around the HCC nodules after the infusion, suggesting that they were infused precisely to the targeted nodules and stayed alive longer than expected. If DCs died after the infusion, the radioactive materials should have been released from the labelled DCs. Furthermore, they seemed to contribute to the recruitment and activation of immune cells by immunohistochemical analysis. In this procedure, immature DCs that did not express CD83 molecule were infused to liver tissues, and only a few infiltrating inflammatory cells were reported to express CD83 in liver tissues [42,49]. However, many immune cells were shown to express CD83 in the tissues surrounding the treated HCC nodules. As CD83 expression is known to be limited on mature DCs and activated B lymphocytes [50,51], the infused immature DCs were suggested to become mature after the infusion, and to recruit activated lymphocytes in the liver tissues.

Interestingly, the results demonstrate that the antigen-non-specific, immature DC infusion may induce the immune responses to unprimed tumour antigens. Because immature DCs are known to display high endocytic and phagocytic activity [52,53], they can take up tumour antigens in the apoptotic tissues treated with TAE therapy. Following the endocytosis and phagocytosis of tumour antigens, DCs may move to secondary lymphoid organs, including regional lymph nodes, become activated and mature and induce antigen-specific cell-mediated and humoral immune responses. Even uncharacterized antigens can be processed and presented to the host immune systems by DCs in this study, and the immune responses to unprimed antigens may be induced. The current in vivo immune induction may omit the identification of tumour antigenic epitopes from the development of tumour immunotherapy.

The recurrence-free survival rates were not increased significantly by this strategy. This therapeutic effect was probably limited due to the insufficient anti-tumour immune responses. To enhance the tumour antigen presentation to T lymphocytes, DCs could be transduced with MHC class I and class II genes [54,55] and co-stimulatory molecules, e.g. CD40, CD80 and CD86 [56,57], and loaded with tumour-associated antigens including tumour lysates, peptides and RNA transfection [58]. To induced natural killer (NK) and NK T cell activation, DCs could be stimulated and modified to produce larger amounts of cytokines, e.g. IL-12, IL-18 and type I IFN [57,59]. Furthermore, DC migration in secondary lymphoid organs could be induced by expression and transduction of chemokine genes, e.g. CCR7 [60–62], by maturation using inflammatory cytokines [63], matrix metalloproteinases and Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands [64], and by combination of different administration routes including i.v. and i.d. injections [65]. Importantly, the current study suggests an initial strategy to develop a novel immunotherapy with DCs for the prevention of HCC recurrence.

Acknowledgments

We thank Akemi Nakano, Chiharu Minami, Yuzu Hasebe and Hitomi Fuke for technical assistance.

References

- 1.Tsukuma H, Hiyama T, Tanaka S, et al. Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with chronic liver disease. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1797–801. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199306243282501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Velazquez RF, Rodriguez M, Navascues CA, et al. Prospective analysis of risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2003;37:520–7. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sangiovanni A, Del Ninno E, Fasani P, et al. Increased survival of cirrhotic patients with a hepatocellular carcinoma detected during surveillance. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1005–14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ercolani G, Grazi GL, Ravaioli M, et al. Liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma on cirrhosis: univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors for intrahepatic recurrence. Ann Surg. 2003;237:536–43. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000059988.22416.F2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poon RT, Fan ST, Ng IO, Lo CM, Liu CL, Wong J. Different risk factors and prognosis for early and late intrahepatic recurrence after resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;89:500–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Omata M, Tateishi R, Yoshida H, Shiina S. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma by percutaneous tumor ablation methods: ethanol injection therapy and radiofrequency ablation. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S159–66. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakamoto Y, Guidotti LG, Kuhlen CV, Fowler P, Chisari FV. Immune pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp Med. 1998;188:341–50. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butterfield LH. Immunotherapeutic strategies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S232–41. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palucka K, Banchereau J. Dendritic cells: a link between innate and adaptive immunity. J Clin Immunol. 1999;19:12–25. doi: 10.1023/a:1020558317162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banchereau J, Briere F, Caux C, et al. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:767–811. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pulendran B, Banchereau J, Maraskovsky E, Maliszewski C. Modulating the immune response with dendritic cells and their growth factors. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:41–7. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(00)01794-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villadangos JA, Schnorrer P, Wilson NS. Control of MHC class II antigen presentation in dendritic cells: a balance between creative and destructive forces. Immunol Rev. 2005;207:191–205. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gregoire M, Ligeza-Poisson C, Juge-Morineau N, Spisek R. Anti-cancer therapy using dendritic cells and apoptotic tumour cells: pre-clinical data in human mesothelioma and acute myeloid leukaemia. Vaccine. 2003;21:791–4. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00600-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanchez-Sanchez N, Riol-Blanco L, Rodriguez-Fernandez JL. The multiple personalities of the chemokine receptor CCR7 in dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:5153–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.9.5153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bayry J, Lacroix-Desmazes S, Kazatchkine MD, Hermine O, Tough DF, Kaveri SV. Modulation of dendritic cell maturation and function by B lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2005;175:15–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crittenden MR, Thanarajasingam U, Vile RG, Gough MJ. Intratumoral immunotherapy: using the tumour against itself. Immunology. 2005;114:11–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.02001.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Figdor CG, de Vries IJ, Lesterhuis WJ, Melief CJ. Dendritic cell immunotherapy: mapping the way. Nat Med. 2004;10:475–80. doi: 10.1038/nm1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McIlroy D, Gregoire M. Optimizing dendritic cell-based anticancer immunotherapy: maturation state does have clinical impact. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2003;52:583–91. doi: 10.1007/s00262-003-0414-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ribas A, Butterfield LH, Glaspy JA, Economou JS. Current developments in cancer vaccines and cellular immunotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2415–32. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsu FJ, Benike C, Fagnoni F, et al. Vaccination of patients with B-cell lymphoma using autologous antigen-pulsed dendritic cells. Nat Med. 1996;2:52–8. doi: 10.1038/nm0196-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nestle FO, Alijagic S, Gilliet M, et al. Vaccination of melanoma patients with peptide- or tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cells. Nat Med. 1998;4:328–32. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tjoa BA, Simmons SJ, Elgamal A, et al. Follow-up evaluation of a phase II prostate cancer vaccine trial. Prostate. 1999;40:125–9. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19990701)40:2<125::aid-pros8>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Albert ML, Sauter B, Bhardwaj N. Dendritic cells acquire antigen from apoptotic cells and induce class I-restricted CTLs. Nature. 1998;392:86–9. doi: 10.1038/32183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albert ML, Pearce SF, Francisco LM, et al. Immature dendritic cells phagocytose apoptotic cells via alphavbeta5 and CD36, and cross-present antigens to cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1359–68. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.7.1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rai R, Richardson C, Flecknell P, Robertson H, Burt A, Manas DM. Study of apoptosis and heat shock protein (HSP) expression in hepatocytes following radiofrequency ablation (RFA) J Surg Res. 2005;129:147–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2005.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobayashi N, Ishii M, Ueno Y, et al. Co-expression of Bcl-2 protein and vascular endothelial growth factor in hepatocellular carcinomas treated by chemoembolization. Liver. 1999;19:25–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.1999.tb00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mizukoshi E, Nakamoto Y, Tsuji H, Yamashita T, Kaneko S. Identification of alpha-fetoprotein-derived peptides recognized by cytotoxic T lymphocytes in HLA-A24+ patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1194–204. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Makuuchi M. General rules for the clinical and pathological study of primary liver cancer. 2nd English edn. Tokyo: Kanehara Ltd; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reddy A, Sapp M, Feldman M, Subklewe M, Bhardwaj N. A monocyte conditioned medium is more effective than defined cytokines in mediating the terminal maturation of human dendritic cells. Blood. 1997;90:3640–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dhodapkar MV, Steinman RM, Sapp M, et al. Rapid generation of broad T-cell immunity in humans after a single injection of mature dendritic cells. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:173–80. doi: 10.1172/JCI6909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Altfeld MA, Trocha A, Eldridge RL, et al. Identification of dominant optimal HLA-B60- and HLA-B61-restricted cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) epitopes: rapid characterization of CTL responses by enzyme-linked immunospot assay. J Virol. 2000;74:8541–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.18.8541-8549.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goulder PJ, Brander C, Annamalai K, et al. Differential narrow focusing of immunodominant human immunodeficiency virus gag-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses in infected African and caucasoid adults and children. J Virol. 2000;74:5679–90. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.12.5679-5690.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ikeda-Moore Y, Tomiyama H, Miwa K, et al. Identification and characterization of multiple HLA-A24-restricted HIV-1 CTL epitopes. strong epitopes are derived from V regions of HIV-1. J Immunol. 1997;159:6242–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuzushima K, Hayashi N, Kimura H, Tsurumi T. Efficient identification of HLA-A*2402-restricted cytomegalovirus-specific CD8(+) T-cell epitopes by a computer algorithm and an enzyme-linked immunospot assay. Blood. 2001;98:1872–81. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.6.1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arai J, Yasukawa M, Ohminami H, Kakimoto M, Hasegawa A, Fujita S. Identification of human telomerase reverse transcriptase-derived peptides that induce HLA-A24-restricted antileukemia cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Blood. 2001;97:2903–7. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.9.2903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanaka H, Tsunoda T, Nukaya I, et al. Mapping the HLA-A24-restricted T-cell epitope peptide from a tumour-associated antigen HER2/neu: possible immunotherapy for colorectal carcinomas. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:94–9. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamada A, Kawano K, Koga M, Matsumoto T, Itoh K. Multidrug resistance-associated protein 3 is a tumor rejection antigen recognized by HLA-A2402-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6459–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mizukoshi E, Nakamoto Y, Marukawa Y, et al. Cytotoxic T cell responses to human telomerase reverse transcriptase in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2006;43:1284–94. doi: 10.1002/hep.21203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xian ZH, Zhang SH, Cong WM, Wu WQ, Wu MC. Overexpression/amplification of HER-2/neu is uncommon in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:500–3. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.023556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nies AT, Konig J, Pfannschmidt M, Klar E, Hofmann WJ, Keppler D. Expression of the multidrug resistance proteins MRP2 andMRP3 in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:492–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vicari AP, Chiodoni C, Vaure C, et al. Reversal of tumor-induced dendritic cell paralysis by CpG immunostimulatory oligonucleotide and anti-interleukin 10 receptor antibody. J Exp Med. 2002;196:541–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen S, Akbar SM, Tanimoto K, et al. Absence of CD83-positive mature and activated dendritic cells at cancer nodules from patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: relevance to hepatocarcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2000;148:49–57. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(99)00312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dhodapkar MV, Steinman RM, Krasovsky J, Munz C, Bhardwaj N. Antigen-specific inhibition of effector T cell function in humans after injection of immature dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2001;193:233–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.2.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adachi E, Maeda T, Matsumata T, et al. Risk factors for intrahepatic recurrence in human small hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:768–75. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90450-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tarao K, Takemiya S, Tamai S, et al. Relationship between the recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and serum alanine aminotransferase levels in hepatectomized patients with hepatitis C virus-associated cirrhosis and HCC. Cancer. 1997;79:688–94. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970215)79:4<688::aid-cncr5>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Imamura H, Matsuyama Y, Tanaka E, et al. Risk factors contributing to early and late phase intrahepatic recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy. J Hepatol. 2003;38:200–7. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00360-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shiratori Y, Shiina S, Teratani T, et al. Interferon therapy after tumor ablation improves prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma associated with hepatitis C virus. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:299–306. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mahmood S, Niiyama G, Kawanaka M, et al. Long term follow-up of a group of chronic hepatitis C patients treated with anti-inflammatory drugs following initial interferon therapy. Hepatol Res. 2002;24:213. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6346(02)00085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tanimoto K, Akbar SM, Michitaka K, Horiike N, Onji M. Antigen-presenting cells at the liver tissue in patients with chronic viral liver diseases: CD83-positive mature dendritic cells at the vicinity of focal and confluent necrosis. Hepatol Res. 2001;21:117–25. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6346(01)00084-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou LJ, Schwarting R, Smith HM, Tedder TF. A novel cell-surface molecule expressed by human interdigitating reticulum cells, Langerhans cells, and activated lymphocytes is a new member of the Ig superfamily. J Immunol. 1992;149:735–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hart DN. Dendritic cells: unique leukocyte populations which control the primary immune response. Blood. 1997;90:3245–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cyster JG. Chemokines, sphingosine-1-phosphate, and cell migration in secondary lymphoid organs. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:127–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trombetta ES, Mellman I. Cell biology of antigen processing in vitro and in vivo. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:975–1028. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lemos MP, Fan L, Lo D, Laufer TM. CD8alpha+ and CD11b+ dendritic cell-restricted MHC class II controls Th1 CD4+ T cell immunity. J Immunol. 2003;171:5077–84. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lemos MP, Esquivel F, Scott P, Laufer TM. MHC class II expression restricted to CD8alpha+ and CD11b+ dendritic cells is sufficient for control of Leishmania major. J Exp Med. 2004;199:725–30. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ni K, O'Neill HC. The role of dendritic cells in T cell activation. Immunol Cell Biol. 1997;75:223–30. doi: 10.1038/icb.1997.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Andrews DM, Andoniou CE, Scalzo AA, et al. Cross-talk between dendritic cells and natural killer cells in viral infection. Mol Immunol. 2005;42:547–55. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Heiser A, Coleman D, Dannull J, et al. Autologous dendritic cells transfected with prostate-specific antigen RNA stimulate CTL responses against metastatic prostate tumors. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:409–17. doi: 10.1172/JCI14364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–52. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Forster R, Schubel A, Breitfeld D, et al. CCR7 coordinates the primary immune response by establishing functional microenvironments in secondary lymphoid organs. Cell. 1999;99:23–33. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dieu-Nosjean MC, Vicari A, Lebecque S, Caux C. Regulation of dendritic cell trafficking: a process that involves the participation of selective chemokines. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:252–62. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.2.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Understanding dendritic cell and T-lymphocyte traffic through the analysis of chemokine receptor expression. Immunol Rev. 2000;177:134–40. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.17717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.MartIn-Fontecha A, Sebastiani S, Hopken UE, et al. Regulation of dendritic cell migration to the draining lymph node: impact on T lymphocyte traffic and priming. J Exp Med. 2003;198:615–21. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ratzinger G, Stoitzner P, Ebner S, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases 9 and 2 are necessary for the migration of Langerhans cells and dermal dendritic cells from human and murine skin. J Immunol. 2002;168:4361–71. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mullins DW, Sheasley SL, Ream RM, Bullock TN, Fu YX, Engelhard VH. Route of immunization with peptide-pulsed dendritic cells controls the distribution of memory and effector T cells in lymphoid tissues and determines the pattern of regional tumor control. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1023–34. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]