Abstract

Histone chaperones assemble and disassemble nucleosomes in an ATP-independent manner and thus regulate the most fundamental step in the alteration of chromatin structure. The molecular mechanisms underlying histone chaperone activity remain unclear. To gain insights into these mechanisms, we solved the crystal structure of the functional domain of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT at a resolution of 2.3 Å. We found that SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT formed a dimer that assumed a “headphone”-like structure. Each subunit of the SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT dimer consisted of an N terminus, a backbone helix, and an “earmuff” domain. It resembles the structure of the related protein NAP-1. Comparison of the crystal structures of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT and NAP-1 revealed that the two proteins were folded similarly except for an inserted helix. However, their backbone helices were shaped differently, and the relative dispositions of the backbone helix and the earmuff domain between the two proteins differed by ≈40°. Our biochemical analyses of mutants revealed that the region of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT that is engaged in histone chaperone activity is the bottom surface of the earmuff domain, because this surface bound both core histones and double-stranded DNA. This overlap or closeness of the activity surface and the binding surfaces suggests that the specific association among SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT, core histones, and double-stranded DNA is requisite for histone chaperone activity. These findings provide insights into the possible mechanisms by which histone chaperones assemble and disassemble nucleosome structures.

Keywords: nucleosome, chromatin, transcription, replication, repair

Eukaryotic DNA is packaged into nucleosomes that consist of dsDNA and four different basic proteins (H2A, H2B, H3, and H4) called core histones (1, 2). Three types of factors are known to be involved in altering chromatin structure, namely, histone-modifying enzymes, ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling complexes, and histone chaperones (3–8). The roles played by the two former enzymes in chromatin remodeling have been extensively studied. However, much less is understood about the molecular mechanisms underlying histone chaperone activity, which assemble or disassemble the DNA around core histones and thereby form and disrupt the nucleosome, respectively.

In general, a molecular chaperone is a molecule that associates with a target protein and prevents its aggregation. Because histones and DNA form aggregates when mixed directly under physiological conditions, histone chaperones must associate with free histones to prevent their improper interactions with DNA. In addition, histone chaperones facilitate the accurate deposition of free histones onto DNA. Conversely, histone chaperones also play important roles in the removal of histones from nucleosomes, which must occur before the DNA can be replicated (9), repaired (10), and transcribed (11). All histone chaperones have nucleosome assembly activity, and at least some, and perhaps all, including CIA/ASF1, have nucleosome disassembly activity (12). Some histone chaperones function with components of several chromatin-related complexes, including histone acetyltransferases (13), histone deacetylases (14), and ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling complexes (15). Thus, in concert with other chromatin-related factors, histone chaperones play an important role in nuclear events that involve chromatin templates.

Although the structure of histone chaperones has been studied such structural analyses have not particularly advanced our understanding of the molecular bases underlying histone chaperone activity (16–21). For example, although structural analysis of nucleoplasmin advocates a model of its histone storage activity, it did not explain how nucleoplasmin functions in nucleosome assembly (16). To address the molecular basis of histone chaperone activity in more detail, we here analyzed the structure of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT. SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT was first identified as a translocation breakpoint-encoded protein in acute undifferentiated leukemia (22). It is a multifunctional protein that has been shown to bind preferentially to histone H3 (23–25), exhibit histone chaperone activity (26), interact with various factors such as DNA-binding proteins (27, 28) and proteases (29), and regulate transcription (27, 28, 30, 31), replication (32), and apoptosis (33). In addition, SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT inhibits the activity of histone acetyltransferases, which suggests that it regulates the nuclear activity that arises from the chemical modification of core histones (34).

Here, we determined the crystal structure of the functional domain of human SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT and compared it to that of yeast NAP-1 (21). As we show here, this histone chaperone adopts a symmetrical dimerized form that has a “headphone”-like shape, which is interesting given that histones form symmetrical octamers. Moreover, the fact that it forms dimers suggests that it may function differently from other histone chaperones such as the nucleoplasmin family, which forms a decamer (16, 18) and CIA/ASF1, which exists as a monomer (17, 19, 20). Mutational analysis revealed that the bottom of the “earmuff domain” of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT binds both core histones and dsDNA and is also involved in regulating histone chaperone activity. This overlap or closeness of the binding surfaces suggests that the specific association among SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT, core histones and dsDNA plays a key role in histone chaperone activity. Thus, the structural analysis of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT may provide further insights into why some histone chaperones have disparate functions. Collectively, our findings provide insights into the action of histone chaperones.

Results

The Acidic Stretch of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT Is Unnecessary for Either Its Histone Chaperone or Core Histone-Binding Activities.

Histone chaperones often exhibit long acidic stretches; however, recent studies have shown that removal of these residues from NAP-1, nucleoplasmin, CIA/ASF1, and NO38 does not impair their histone chaperone or core histone-binding activities (16–18, 21, 35, 36).

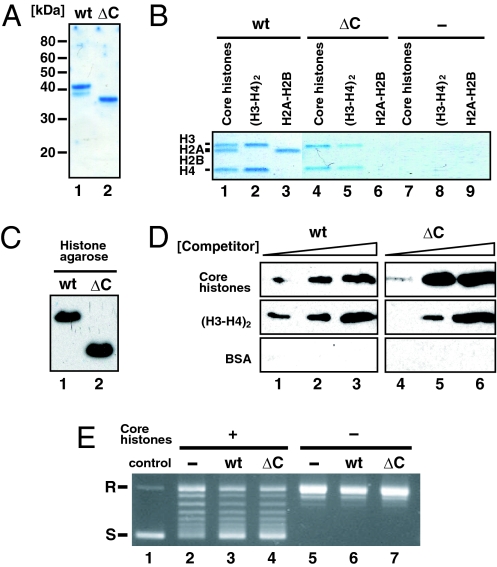

To determine whether the acidic stretch of ≈40 aa in the C-terminal region of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT is required for its core histone-binding and histone chaperone activities, we purified a protein containing only the N-terminal amino acids 1–225, which lacks the acidic stretch (Fig. 1A). On Ni-NTA pull-down assay, the WT protein bound all four core histones whereas the ΔC deletion protein bound histones H3 and H4 (Fig. 1B). This implies that the N-terminal region of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT is sufficient for the binding activity to histone H3 and H4. On the other hand, the C-terminal acidic stretch is required to form a complex with all core histones, H2A, H2B, H3, and H4. In addition, both of the WT and SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT ΔC proteins bound histone–agarose (Fig. 1C) and eluted off when adding histone H3 and H4 as a competitor (Fig. 1D). We confirmed that SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT specifically bound histone–agarose but not protein A-agarose (data not shown). Although the histone binding activities are different between WT and ΔC proteins (Fig. 1B), the two showed similar histone chaperone activities (Fig. 1E). Thus, the acidic stretch of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT was not necessary for binding activity to histone H3 and H4 and histone chaperone activity, although it was required for histone H2A–H2B binding activity. These results showed that SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT has histone chaperone activity specific to histone H3 and H4. Therefore, to investigate the molecular basis underlying the histone chaperone activity of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT, we determined the crystal structure of the SET/TAF-Iβ/INHATΔC mutant (37).

Fig. 1.

Functional activities of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHATΔC. (A) Coomassie brilliant blue staining of purified SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT WT (lane 1) and ΔC (lane 2) proteins. (B) Complex formation of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT with core histones. After incubating histones H2A–H2B, H3, and H4, or all four core histones with Ni-NTA agarose beads, which captured SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT WT (lanes 1–3), ΔC (lanes 4–6), and no protein (lanes 7–9), the bead-bound fraction was resolved by SDS/PAGE and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. (C) Interaction of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT WT (lane 1) and ΔC (lane 2) proteins with histone–agarose. (D) Histone binding specificity of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT WT and ΔC by competition assay. Shown is eluted SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT in supernatant after addition of 100 pmol (lanes 1 and 4), 350 pmol (lanes 2 and 5), and 1,000 pmol (lanes 3 and 6) of competitor proteins [core histones, (H3-H4)2, and BSA] to SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT-bound histone–agarose. (E) Histone chaperone activity of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHATΔC. Circular plasmid DNA (lane 1) was relaxed by topoisomerase I and then incubated with (lanes 2–4) or without (lanes 5–7) core histones plus SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT WT (lanes 3 and 6), SET/TAF-Iβ/INHATΔC (lanes 4 and 7), or no protein (lanes 2 and 5). Under these conditions, a small amount of supercoiled DNA formed in the absence of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT (lane 2). R, relaxed; S, supercoiled.

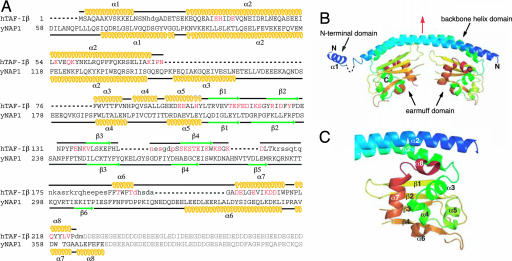

SET/TAF-Iβ/INHATΔC Dimers Assume a Headphone-Like Shape.

We determined the crystal structure of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHATΔC by the MAD method [supporting information (SI) Table 1]. SET/TAF-Iβ/INHATΔC forms a dimer that assumes a headphone-like shape. The dimers are ≈110 × 50 × 50 Å3 in size, and each subunit consists of an N terminus, a backbone helix, and an earmuff domain (amino acids 1–24, 25–78, and 79–225, respectively) (Fig. 2 A and B). SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT and its putative alternatively spliced variant TAF-Iα differ only in their N-terminal domains (38). This domain is probably highly mobile in solution because the electron density of the residues between the α1- and α2-helices could not be observed (Fig. 2A). In the crystal, the α1-helix is sandwiched by two earmuff domains originating from the adjacent molecule. It remains unclear whether this interaction is of biological significance.

Fig. 2.

Structure of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHATΔC. (A) Amino acid sequences of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT and NAP-1. The α-helices (yellow) and β-strands (green) in the sequences are indicated. Residues modified by site-directed mutagenesis (see Fig. 4 A–C and SI Table 2) are red, and those with no observable electron density are not capitalized. Residues in the acidic stretch are gray. (B) Overall structure of the SET/TAF-Iβ/INHATΔC dimer, with the pseudo twofold axis highlighted in red. (C) The structure of the earmuff domain.

The 51-aa-long backbone helix is bent at ≈50°, and in the dimer the two backbone helices interact hydrophobically in an antiparallel manner (SI Fig. 5 A and B). A pseudo twofold axis runs perpendicular to the backbone helix (Fig. 2B and SI Fig. 5 A and B). The residues contributing to dimer formation are A31, H34, I35, V38, I42, L45, A49, I53, V56, Y60, R64, F67, F68, R71, L74, and I78 (SI Fig. 5B). This finding is compatible with a report showing that the V38E/I42S/L45E/A49E and V38S/I42S/L45S/A49S mutants are unable to dimerize (39). The earmuff domain, which is attached to the concave side of the backbone helix, forms an α+β structure in which six α-helices are located on four-stranded antiparallel β-sheets (Fig. 2C). The electron density of the residues between the β4-strand and α6-helix (residues 168–188) could not be observed (Fig. 2A), which suggests that the lower part of the earmuff domain is highly mobile in aqueous solution. This is supported by the fact that the peptide bond between amino acid residues K176 and A177, which are located in this putative mobile region, is reported to be cleaved by the cytotoxic T lymphocyte protease granzyme A (40).

Structural Comparison with NAP-1.

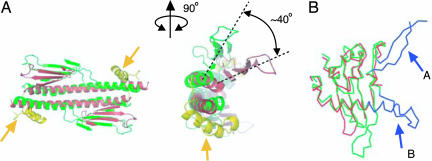

The primary structure of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT is similar to that of NAP-1 (Fig. 2A), whose crystal structure was reported very recently (21). Comparison of the crystal structure of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT with that of NAP-1 revealed that the two proteins are also folded similarly except for a helix of NAP-1 (helix α3) that has been inserted between the backbone helix (part of domain I) and the earmuff domain (domain II) [the domains of NAP-1 that are shown in parentheses refer to the previously published designations (21)] (Fig. 2A). The rms deviation derived from the least-squares fittings of the corresponding 156 Cα atoms of each subunit was on average 3 Å. This large rms deviation is mainly due to two reasons. First, the shapes of the backbone helices differ, as a top view of the NAP-1 backbone helix shows a sigmoid shape (21) whereas that of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT is nearly straight (Fig. 3A). Second, the relative disposition of the backbone helix and the earmuff domain differs between the two proteins, as an outward rotation of ≈40° is required to superimpose the earmuff domain of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT onto the corresponding domain of NAP-1 (Fig. 3A). In addition, the disposition of the N-terminal helices of the two proteins differ, because helix α1 of NAP-1 interacts with the earmuff domain (domain II) of another subunit in the dimer whereas the corresponding helix (α1) of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT interacts with an adjacent dimer molecule in the crystal lattice.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the structures of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT and NAP-1. (A) Bottom (Left) and front (Right) views of the superimposed structures of NAP-1 (green) and SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT (red). The yellow helices indicated by the arrows are the extra helix of NAP-1 that is inserted between the backbone helix and the earmuff domain (domain II). The rotation angle for the superimposition of the earmuff domains of NAP-1 and SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT is given in the front view. Helices in the earmuff domain are not shown for clarity. (B) The superimposition of the earmuff domains of NAP-1 (green and blue) and SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT (red). The extra residues that are unique to the NAP-1 structure are shown in blue. The corresponding residues of fragment A could not be modeled in the present study because of disordering. Fragment B is a long insertion of NAP-1 (see Fig. 2A).

Despite these differences, the core structures of the earmuff domains of the two proteins are similar with an average rms deviation of 1.9 Å for 106 Cα atoms. The highly conserved hydrophobic cores of the two proteins suggest that they are evolutionarily closely related. The differences between the earmuff domains of the two proteins exist in helix α7 of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT, as the corresponding helix of NAP-1 (helix α6) is ≈10 residue longer (Figs. 2A and 3B) and protrudes from the earmuff domain. Additionally, there are some deletions in the loop region of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT compared with that of NAP-1 (Figs. 2A and 3A).

The Electrostatic Potential of the SET/TAF-Iβ/INHATΔC Dimer.

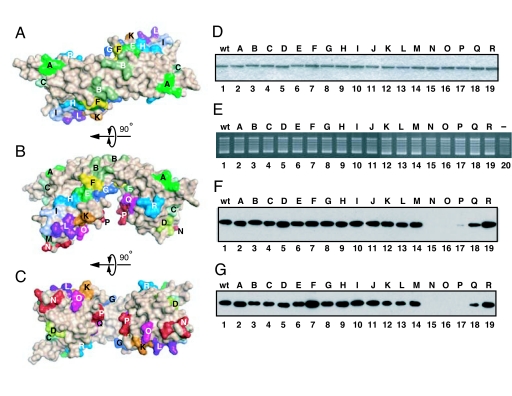

Analysis of the electrostatic potential of the SET/TAF-Iβ/INHATΔC dimer indicates that the convex surface of the backbone helix is positively charged because of the basic residues K26, R44, K59, K62, K70, and K77 (SI Fig. 6A). The electrostatic properties of the two sides of the earmuff domain differ; SET/TAF-Iβ/INHATΔC has both acidic and basic faces (SI Fig. 6B). The α-helix side of the earmuff domain contains negatively charged acidic residues (E98, E101, E102, D165, D202, E203, E206, D210, and D211), and this negatively charged area extends across the same side of the backbone helix (E25, E33, D36, E37, D43, E47, and E51). In addition, there are only three basic residues on this surface (H89, H105, and K164). In contrast, the opposite surface possesses more basic than acidic residues (14 vs. 11), resulting in a slightly positively charged surface. Because it was difficult to predict from the electrostatic potentials which surfaces were critical for histone chaperone function, we mutated most of the surface amino acid residues in sets of three (Figs. 2A and 4 A–C). This helped us to identify the functional region, as described below.

Fig. 4.

Mapping of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT activities. (A–C) Location of triple mutated residue sets as observed from the top view (A), side view (B), and bottom view (C) of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT. For detailed information, see SI Table 2. (D) SDS/PAGE of the SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT WT and mutant proteins and staining with Coomassie brilliant blue. For full gel information, see SI Fig. 7. (E) Histone chaperone activities of the SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT WT and mutant proteins. The estimated relative net activity of each mutant is as follows: WT, 100; A, 103; B, 94; C, 98; D, 87; E, 91; F, 97; G, 99; H, 97; I, 104; J, 98; K, 98; L, 93; M, 88; N, 38; O, 36; P, 67; Q, 64; R, 95 (see Materials and Methods). (F and G) Histone-binding (F) and dsDNA-binding (G) activities of the SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT WT and mutant proteins. The bound proteins were detected by immunoblot analysis using anti-His antibodies. Mutants N, O, and P demonstrated impaired binding activities. The estimated relative histone binding activity of each mutant is as follows: WT, 100; A, 98; B, 101; C, 91; D, 127; E, 98; F, 108; G, 103; H, 101; I, 108; J, 106; K, 96; L, 81; M, 100; N, 0; O, 0; P, 5; Q, 70; R, 122. The estimated relative DNA binding is as follows: WT, 100; A, 71; B, 89; C, 114; D, 121; E, 123; F, 117; G, 124; H, 138; I, 88; J, 77; K, 79; L, 73; M, 64; N, 5; O, 7; P, 0; Q, 29; R, 59 (see Materials and Methods).

The Earmuff Domain Binds Both Core Histones and dsDNA and Is Involved in Histone Chaperone Activity.

We constructed 18 mutants in which three spatially successive amino acid residues were converted into alanine residues (Fig. 4 A–C and SI Table 2) and purified these proteins to near homogeneity (Fig. 4D and SI Fig. 7). The expression, solubilization, and purification of all mutant proteins were almost the same as those of the WT protein. Mutants N (S162A/K164A/D165A) and O (T191A/T194A/D195A), whose modifications were located at the bottom of the earmuff domain, demonstrated impaired histone chaperone activity (≈35% of WT activity) (Fig. 4E). In addition, the activities of mutants P (D202A/E203A/E206A) and Q (K209A/D210A/D211A) were marginally decreased (≈65% of WT activity).

Further mapping of the histone-binding surface indicated that mutants N, O, and P exhibited decreased interaction with core histones (Fig. 4F). The triple mutations of N, O, and P form a line from the lower region of the earmuff domain to its internal side (Fig. 4C and SI Fig. 8). It is of note that the CD spectra of the mutants N, O, P, and Q showed that these mutants folded properly (data not shown). Given that histone chaperones regulate interactions between core histones and DNA, it is possible that these proteins interact directly with both molecules. Thus, we investigated the association of WT and mutant SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT proteins with dsDNA and found impaired binding in mutants N, O, and P (Fig. 4G). Although the bottom of the earmuff domain is negatively charged (SI Fig. 6C), the region where the electron density is not observed (residues 168–188) and which may cover the negatively charged surface has several basic residues, namely, three lysine and three arginine residues (Fig. 2A). Our experiments with the 18 mutants suggest that this lower part of the earmuff domain is used for binding both core histones and dsDNA and thus is responsible for the histone chaperone activity of the protein.

Discussion

Structural analysis of the functional domain of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT revealed that it forms a dimer with a headphone-like structure. Recently, the structure of NAP-1, a related histone chaperone, was reported (21). Although the overall structures of NAP-1 and SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT were similar, the relative disposition of the earmuff domains differed significantly. This structural disparity may be responsible for some differences in how the structures of the two proteins relate to their functions. Park and Luger (21) predicted that the acidic lower part of the earmuff domain of NAP-1, with the support of the acidic stretch, is involved in neutralizing and binding the basic N-terminal histone tails. In NAP-1, the lower part of the earmuff domain (domain II) is composed of the α1-, α4-, α5-, and α6-helices along with a short helix between α4 and α5 (Fig. 3A). Our biochemical analysis of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT, however, did not suggest that the corresponding helices of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT (α1, α3, α4, α5, and α7) are involved in histone binding. Instead, residues on helix α6, on the loop after β4, and on the N-terminal part of the helix α7 were identified to interact with histones (Fig. 4F). If the equivalent residues would be involved in the histone binding of NAP-1, this would result in two putative binding sites in the NAP-1 dimer that face distinct directions; as a result, NAP-1 could interact with two histone molecules (or complexes) (Fig. 3A). Alternatively, NAP-1 and SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT simply might use different residues to bind histones. Clarification of this issue will require the functional analysis of NAP-1 based on its tertiary structure.

Our structural and biochemical analyses demonstrated that the bottom of the earmuff domain of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT interacts with both dsDNA and core histones. The strong correlation between the DNA-binding and histone chaperone activities of the SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT triple mutants suggests that the DNA-binding of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT is a requisite step in its histone chaperone activity. Because the dsDNA- and core histone-binding surfaces in SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT overlap (or lie very closely adjacent to each other), the dsDNA and core histones may be closely enough juxtaposed upon binding to the earmuff domain that they form a prenucleosome complex with SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT. SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT could then guide the dsDNA onto specific sites of the core histones and thereby determine the initiation site for DNA-winding. These specific interactions between the three components thus appear to play a fundamental role in the histone chaperone activity of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT. Such specific interactions could also prevent the nonproductive aggregation of the components.

DNA, histones, and SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT may associate in two different ways. The first scenario involves a complex that is composed only of DNA, histones, and SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT. In this complex, either both earmuff domains of the dimer bind histones and DNA simultaneously or one earmuff domain binds histones while the other binds DNA. In the second scenario, the complex includes not just DNA, histones, and SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT but also another factor or an additional molecule of SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT acts as a bridge between the SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT-histone and SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT-DNA complexes. Further cocrystal structural studies will provide a greater understanding of the relationship between the structures of histone chaperones and their chaperone functions.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of Recombinant Proteins.

The SET/TAF-Iβ/INHATΔC region was PCR-amplified and subcloned into pET14b (Novagen, Darmstadt, Germany). The SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT triple mutation constructs were generated by site-directed PCR mutagenesis. The His-tagged SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT WT, ΔC, and mutant proteins were overexpressed and purified as described previously (37). Before histone-binding, DNA-binding, and histone chaperone assays, the recombinant proteins were dialyzed in dialysis buffer [20 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.9), 100 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 0.5 mM PMSF].

Histone Chaperone Assay.

Histone chaperone activity was measured as described previously (36). Briefly, 3 pmol SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT (WT or mutants) and 2 pmol core histones were allowed to form complexes in assembly buffer [10 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 100 μg·ml−1 BSA] during a 15-min incubation at 30°C. Circular DNA (0.05 pmol) was relaxed by using 5 units of topoisomerase I (Promega, Madison, WI), then incubated with the histone chaperone/histone complexes at 30°C for 45 min. The reactions were stopped by adding a 1/3 volume of stop buffer (1% SDS and 500 μg·ml−1 proteinase K) followed by incubation at 30°C for 15 min. The plasmids were then extracted by using phenol-chloroform followed by ethanol precipitation and separated by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The histone chaperone assay was done in duplicate. The DNA bands were quantified by densitometry using the program ImageJ (41). The activity of each mutant was calculated as (band density of the supercoiled DNA)/(band density of all of the DNA); these values were expressed as relative activities by normalization with the WT value and background. Core histones were prepared from HeLa cells essentially as described previously (42).

Histone-Binding Assay.

Histone-binding assays were performed by incubating 37.5 μg of histone–agarose [calf thymus core histones conjugated to agarose (Sigma, St. Louis, MO)] with 0.25 pmol His-tagged SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT (WT or mutant proteins) in binding buffer [20 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 0.25 mM PMSF] at 4°C for 30 min, followed by four washes in binding buffer. For competition experiments, increasing amounts of the each competitor protein [recombinant Xenopus laevis core histones or (H3-H4)2, or BSA] were added to the washed agarose in a total of 120 μl of binding buffer. After incubation for 60 min at 4°C, supernatant was separated from agarose beads by centrifugation and precipitated by TCA. Western blot analysis was performed by separating the washed agarose and supernatant by SDS/PAGE and transferring it to a poly(vinylidene difluoride) membrane, followed by probing and visualization using an anti-HIS probe antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and SuperSignal reagents (Pierce, Rockford, IL), respectively. The suitability of these histone–agarose complexes for our histone-binding experiments was substantiated by an experiment that showed that, although GST did not bind to them, the histone-binding corepressor SMRT (43) interacted specifically with them (data not shown). The Western-blotted bands were quantified by densitometry using the program ImageJ (41). The relative activity to WT SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT was then calculated for each mutant.

Ni-NTA Pull-Down Assay.

Ni-NTA pull-down assays were performed by incubating 20 μl of Ni-NTA His·Bind resin (Novagen) with 100 pmol SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT (WT or ΔC proteins) in binding buffer [20 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mM KCl, 20% glycerol, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.1% NP-40, 30 mM imidazole, and 2 mM PMSF] at 4°C for 30 min, followed by washing three times in the same buffer. The matrix-bound proteins were then mixed with X. laevis recombinant histones [50 pmol of core histone, 100 pmol of H2A–H2B, or 50 pmol of (H3-H4)2] in 200 μl of binding buffer at 4°C for 50 min. After washing three times, the bead-bound fraction was resolved by SDS/PAGE and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue.

Crystal Structure Determination.

Three Met residues were introduced at positions 104, 145, and 166 for the MAD phasing (Fig. 2A). The selenomethionyl mutant (L104M, L145M, and L166M) was crystallized by the sitting drop vapor diffusion method as described previously (37). MAD data collections at 100 K were performed by using a Quantum 210 CCD camera at beamline NW12 of Photon Factory (PF)-AR in KEK (Tsukuba, Japan). Diffraction data were processed and scaled by using the program package HKL2000 (44) (SI Table 1). SHELXD (45) and SHARP (46) were used to determine the selenium sites and phases, respectively. Electron-density modification and model building were performed by using SOLMON (47) and XtalView (48), respectively. The high-resolution data set for crystallographic refinement (2.3-Å resolution) was collected at 100 K by using a Quantum 4R CCD camera at beamline 6A of PF in KEK. Crystallographic refinement was performed by using CNS (49) and REFMAC5 (50). The TLS parameters were refined by REFMAC5 (50). The final model comprises 694 residues of the two dimers. A total of 91.3% of all residues fall in the most favored Ramachandran category, with 8.4% in the allowed category, 0% in the generously allowed category, and 0.3% in the disallowed category.

Structural Analysis and Molecular Graphics.

The buried accessible surface area was calculated by the formula [(area of monomer + area of monomer) − area of dimer]. The molecular graphics were prepared by PyMOL (51). Least-squares fittings were carried out by using the program LSQKAB from the CCP4 program suite (52).

DNA-Binding Assay.

The DNA-binding assays were performed by incubating 5 μl of calf thymus dsDNA–cellulose (Sigma) with 0.25 pmol SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT (WT or mutant proteins) in binding buffer at 4°C for 30 min, followed by four washings in the same buffer. Immunoblot analysis was performed as described above. The DNA-binding assay was done in duplicate. The Western-blotted bands were quantified by densitometry using the program ImageJ (41). The relative activity to WT SET/TAF-Iβ/INHAT was then calculated for each mutant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Natsume and N. Adachi for technical support. This research was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Science Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan; the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan; the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization; and Exploratory Research for Advanced Technology of the Japan Science and Technology Agency.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS direct submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 2E50).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0603762104/DC1.

References

- 1.Kornberg RD. Science. 1974;184:868–871. doi: 10.1126/science.184.4139.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luger K, Mader AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Nature. 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Science. 2001;293:1074–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mellor J. Mol Cell. 2005;19:147–157. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horn PJ, Peterson CL. Science. 2002;297:1824–1827. doi: 10.1126/science.1074200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tyler JK. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:2268–2274. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akey CW, Luger K. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13:6–14. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(03)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loyola A, Almouzni G. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1677:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shibahara K, Stillman B. Cell. 1999;96:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80661-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaillard PH, Martini EM, Kaufman PD, Moustacchi E, Almouzni G. Cell. 1996;86:887–896. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80164-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen H, Li B, Workman JL. EMBO J. 1994;13:380–390. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adkins MW, Howar SR, Tyler JK. Mol Cell. 2004;14:657–666. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osada S, Sutton A, Muster N, Brown CE, Yates JR, Jr, Sternglanz R, Workman JL. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3155–3168. doi: 10.1101/gad.907201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kutney SN, Hong R, Macfarlan T, Chakravarti D. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30850–30855. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404969200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LeRoy G, Orphanides G, Lane WS, Reinberg D. Science. 1998;282:1900–1904. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dutta S, Akey IV, Dingwall C, Hartman KL, Laue T, Nolte RT, Head JF, Akey CW. Mol Cell. 2001;8:841–853. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00354-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daganzo SM, Erzberger JP, Lam WM, Skordalakes E, Zhang R, Franco AA, Brill SJ, Adams PD, Berger JM, Kaufman PD. Curr Biol. 2003;13:2148–2158. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Namboodiri VM, Akey IV, Schmidt-Zachmann MS, Head JF, Akey CW. Structure (London) 2004;12:2149–2160. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mousson F, Lautrette A, Thuret JY, Agez M, Courbeyrette R, Amigues B, Becker E, Neumann JM, Guerois R, Mann C, Ochsenbein F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5975–5980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500149102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Padmanabhan B, Kataoka K, Umehara T, Adachi N, Horikoshi M. J Biochem. 2005;138:821–829. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvi182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park Y-J, Luger K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1248–1253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508002103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.von Lindern M, van Baal S, Wiegant J, Raap A, Hagemeijer A, Grosveld G. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:3346–3355. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.8.3346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okuwaki M, Nagata K. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:34511–34518. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.34511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsumoto K, Nagata K, Okuwaki M, Ttsujimoto M. FEBS Lett. 1999;463:285–288. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01632-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seo SB, Macfarlan T, McNamara P, Hong R, Mukai Y, Heo S, Chakravarti D. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:14005–14010. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112455200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawase H, Okuwaki M, Miyaji M, Ohba R, Handa H, Ishimi Y, Fujii-Nakata T, Kikuchi A, Nagata K. Genes Cells. 1996;1:1045–1056. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1996.d01-223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suzuki T, Muto S, Miyamoto S, Aizawa K, Horikoshi M, Nagai R. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28758–28764. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302228200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyamoto S, Suzuki T, Muto S, Aizawa K, Kimura A, Mizuno Y, Nagino T, Imai Y, Adachi N, Horikoshi M, Nagai R. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:8528–8541. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.23.8528-8541.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beresford PJ, Kam CM, Powers JC, Lieberman J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9285–9290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsumoto K, Okuwaki M, Kawase H, Handa H, Hanaoka F, Nagata K. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:9645–9650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gamble MJ, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Freedman LP, Fisher RP. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:797–807. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.2.797-807.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsumoto K, Nagata K, Ui M, Hanaoka F. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:10582–10587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fan Z, Beresford PJ, Oh DY, Zhang D, Lieberman J. Cell. 2003;112:659–672. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seo SB, McNamara P, Heo S, Turner A, Lane WS, Chakravarti D. Cell. 2001;104:119–130. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00196-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fujii-Nakata T, Ishimi Y, Okuda A, Kikuchi A. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:20980–20986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Umehara T, Chimura T, Ichikawa N, Horikoshi M. Genes Cells. 2002;7:59–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1356-9597.2001.00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muto S, Senda M, Adachi N, Suzuki T, Nagai R, Senda T, Horikoshi M. Acta Crystallogr D. 2004;60:712–714. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904001647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nagata K, Kawase H, Handa H, Yano K, Yamasaki M, Ishimi Y, Okuda A, Kikuchi A, Matsumoto K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4279–4283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miyaji-Yamaguchi M, Okuwaki M, Nagata K. J Mol Biol. 1999;290:547–557. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beresford PJ, Zhang D, Oh DY, Fan Z, Greer EL, Russo ML, Jaju M, Lieberman J. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43285–43293. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108137200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abramoff MD, Magelhaes PJ, Ram SJ. Biophotonics Int. 2004;11:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simon RH, Felsenfeld G. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;6:689–696. doi: 10.1093/nar/6.2.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Privalsky ML. Annu Rev Physiol. 2004;66:315–360. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032802.155556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schneider TR, Sheldrick GM. Acta Crystallogr D. 2002;58:1772–1779. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902011678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de La Fortelle E, Bricogne G. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:472–494. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abrahams JP, Leslie AG. Acta Crystallogr D. 1996;52:30–42. doi: 10.1107/S0907444995008754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McRee DE. Practical Protein Crystallography. San Diego: Academic; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brünger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, et al. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Acta Crystallogr D. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.DeLano WL. San Carlos, CA: DeLano Scientific; 2002. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4. Acta Crystallogr D. 1994;50:760–763. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.