Abstract

Background

The genome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis harbors four copies of a cluster of genes termed mce operons. Despite extensive research that has demonstrated the importance of these operons on infection outcome, their physiological function remains obscure. Expanding databases of complete microbial genome sequences facilitate a comparative genomic approach that can provide valuable insight into the role of uncharacterized proteins.

Results

The M. tuberculosis mce loci each include two yrbE and six mce genes, which have homology to ABC transporter permeases and substrate-binding proteins, respectively. Operons with an identical structure were identified in all Mycobacterium species examined, as well as in five other Actinomycetales genera. Some of the Actinomycetales mce operons include an mkl gene, which encodes an ATPase resembling those of ABC uptake transporters. The phylogenetic profile of Mkl orthologs exactly matched that of the Mce and YrbE proteins. Through topology and motif analyses of YrbE homologs, we identified a region within the penultimate cytoplasmic loop that may serve as the site of interaction with the putative cognate Mkl ATPase. Homologs of the exported proteins encoded adjacent to the M. tuberculosis mce operons were detected in a conserved chromosomal location downstream of the majority of Actinomycetales operons. Operons containing linked mkl, yrbE and mce genes, resembling the classic organization of an ABC importer, were found to be common in Gram-negative bacteria and appear to be associated with changes in properties of the cell surface.

Conclusion

Evidence presented suggests that the mce operons of Actinomycetales species and related operons in Gram-negative bacteria encode a subfamily of ABC uptake transporters with a possible role in remodeling the cell envelope.

Background

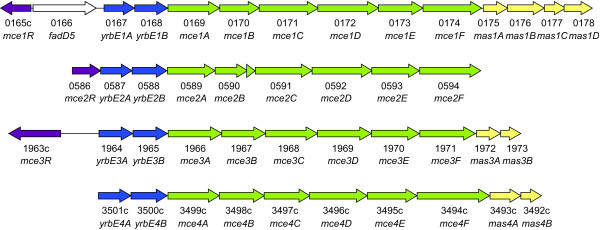

A putative Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence gene, named mce1A, was originally identified because its expression in Escherichia coli enabled this noninvasive bacterium to enter mammalian epithelial cells [1]. Sequencing of the M. tuberculosis genome revealed that mce1A (Rv0169) was part of an operon that encoded eight putative membrane-associated proteins: YrbEA-B, MceA-F [2,3]. This operon is present four times in the M. tuberculosis genome (mce1-4). Homologs of the genes adjacent to the mce1 locus, Rv0175-Rv0178, are located downstream of the mce3 and mce4 gene clusters (Figure 1) [3].

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the M. tuberculosis H37Rv mce loci. Proximal transcription regulators are colored in purple, yrbE genes in blue, mce genes in green, and genes encoding 'conserved mce-associated proteins' in yellow [44].

Continued interest in the function of the M. tuberculosis mce operons stems from reports of the profound effect of disruption of mce operons on growth and virulence of the mutant strains in mice. Shimono et al. [4] showed that an mce1 mutant was hypervirulent when inoculated intravenously into BALB/c mice. In the first few weeks of infection, the mutant strain multiplied more rapidly than wild-type in the mice's lungs, spleen and liver. Surprisingly, Gioffre et al. [5] found that a yrbE1B mutant grew faster than wild-type in the lungs and spleens of BALB/c mice inoculated via the peritoneum, but more slowly in mice infected through the tracheal route. Sassetti and Rubin [6] reported that in competitive mixed infections mce1 mutants exhibited a growth defect in the spleens of intravenously-infected C57BL/6J mice after one week of infection. Although the exact cause of these apparently disparate phenotypes remains to be established, the observations suggest that the fate of mce1 mutants in vivo is determined by the prevailing immunological environment experienced during the first few weeks of infection.

Both mce2 and mce3 mutants replicated slower than wild-type in BALB/c mice infected via either the trachea or peritoneum [5]; however, neither mutant demonstrated a significant growth defect in competitive mixed infections [6]. In co-infected C57BL/6J mice, an mce4 mutant was attenuated relative to wild-type after two to four weeks infection, whilst an mce1-mce4 double mutant exhibited further attenuation, indicating that the mce operons perform non-redundant roles during infection [7].

The similarity of the YrbE and Mce proteins with ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter permeases and substrate-binding proteins, respectively, has been noted previously [8,9]. ABC transporters couple the energy released by ATP hydrolysis to the translocation of a substrate across a membrane. Members of the ABC transporter family are ubiquitous in living organisms and comprise one of largest superfamilies known [10].

A functional ABC transporter system minimally contains two cytoplasmic nucleotide-binding ATPase domains and two transmembrane channel-forming permease domains. These components can be homo- or heterodimers and may be encoded on separate or fused polypeptides. Both eukaryotes and prokaryotes contain ABC exporters, whereas importers have been identified only in prokaryotes. Importers additionally require substrate-binding proteins (SBPs) that provide specificity and high-affinity. Typically, SBPs are periplasmic in Gram-negative bacilli and lipoproteins in Gram-positive bacilli [11]. SBPs share a two-lobed quaternary structure with a central cleft that undergoes a large conformational change upon ligand-binding, promoting close interaction with the cognate permease. This results in hydrolysis of ATP, which energizes translocation of the substrate [12]. In Gram-negative bacteria, SBP-dependent importers also usually require porins or specific receptors to facilitate transport across the outer membrane [11].

The genes encoding the ATPase, permease and SBP components of an ABC transporter are often contiguous in the genome and comprise an operon. Phylogenetic clustering of the individual transporter components is almost always concordant, indicating that the operons have arisen from a common ancestral transporter with minimal shuffling of constituents. In addition, sequence similarity shows good correlation with substrate specificity [13-15].

The ATPase is the most conserved component of the system and transporter function is frequently predicted solely on the basis of ATPase orthology [10,15]. These proteins contain a homologous region, of 200 amino acids, with several characteristic motifs: Walker A and B motifs in the nucleotide-binding fold [16], as well as a signature motif found only in ABC transporter-associated, or 'traffic', ATPases [17].

The permease components and SBPs have limited primary sequence similarity, and thus their identification is not facile. They are typically identified in genome sequences by their proximity to ATPases and, for permeases, possession of predicted transmembrane regions [18-20]. The inference of function through sequence comparison has traditionally relied upon similarity to close homologs of known function. The advent of the genomic age has provided invaluable new methods for the elucidation of roles of proteins with unknown function. Non-homology-based methods of genome comparison use patterns of domain fusion [21], conserved chromosomal location [22], and phylogenetic profiles [23], to predict functional interactions between proteins. In addition, the availability of hundreds of complete genome sequences permits the reliable identification of orthologs, operationally-defined as reciprocal best hits [24], enabling more precise functional prediction than sequence similarity alone. These methods are non-redundant and their application can facilitate deduction of specific function [25]. Here we endeavor to further understand the function of the M. tuberculosis mce operons, and assess the likelihood that they encode ABC transporters, through sequence and genome comparisons, database mining and the application bioinformatic methods.

Results

Distribution of mce operons in Actinomycetales

Perusal of databases of conserved domains, such as InterPro [26], Pfam [27] and TIGRFAM [28], constitutes a simple method for the identification of homologous proteins. The M. tuberculosis H37Rv genome encodes 24 Mce proteins, each of which contains a conserved domain of 304 amino acids defined by the TIGRFAM family: TIGR00996 (IPR005693). Members of this family are confined to the Order Actinomycetales. The corresponding Pfam family, PF02470 (IPR003399), describes a 98 amino acid sub-region of the Mce domain that is more widely distributed (see below). The mce genes in M. tuberculosis are clustered in groups of six; each cluster is preceded by two copies of a gene termed yrbE (Figure 1). Databases of conserved domains group the YrbE proteins into a family called DUF140 (domain of unknown function). Pfam defines the family by a region approximately 150 amino acids long (PF02405; IPR003453). The corresponding TIGRFAM family (TIGR00056) describes a subfamily of DUF140, but excludes the mycobacterial homologs based on a stated extreme divergence at the amino end. For the sake of clarity, we refer to a cluster of genes encoding two YrbE and six Mce proteins as an 'mce operon'.

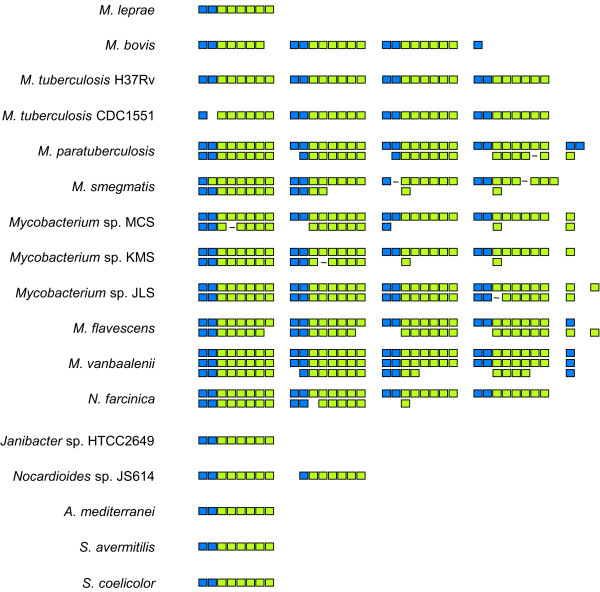

To assess the distribution of mce operons in completed and draft assemblies of genomes of members of the Order Actinomycetales, we surveyed the annotation of predicted proteins for members of Pfam families PF02470 and PF02405 (Table 1). The proteomes of all 10 Mycobacterium species examined contained Mce proteins. The number varied from 6 in Mycobacterium leprae up to 66 in Mycobacterium vanbaalenii. Other genomes containing mce genes belonged to species of Nocardia, Janibacter, Nocardiodes, Amycolatopsis and Streptomyces. Mce homologs were absent from 18 Actinomycetales genomes, notably including those of the four sequenced Corynebacterium species. DUF140 proteins were found encoded within all Actinomycetales genomes that contain mce genes and were absent from all genomes that do not contain mce genes. Other completely sequenced genomes of species belonging to the Class Actinobacteria, namely Rubrobacter xylanophilus, Symbiobacterium thermophilum and Bifidobacterium longum, did not contain either Mce or DUF140 homologs.

Table 1.

Distribution of Mce and YrbE proteins within the Order Actinomycetalesa

| Suborder | Family | Species | Mce b | DUF140 c | Source |

| Actinomycinaeae | Actinomycetaceae | Actinomyces naeslundii MG1 | 0 | 0 | UniProt |

| Corynebacterineae | Corynebacteriaceae | Corynebacterium diphtheriae NCTC 13129 | 0 | 0 | UniProt |

| Corynebacterium efficiens YS-314 | 0 | 0 | UniProt | ||

| Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032 | 0 | 0 | UniProt | ||

| Corynebacterium jeikeium K411 | 0 | 0 | UniProt | ||

| Mycobacteriaceae | Mycobacterium leprae TN | 6 | 2 | UniProt | |

| Mycobacterium bovis AF2122/97 | 18 | 7 | UniProt | ||

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis CDC1551 | 24 | 7 | TIGR | ||

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv | 24 | 8 | TIGR | ||

| Mycobacterium paratuberculosis K-10 | 48 | 14 | UniProt | ||

| Mycobacterium smegmatis MC2 155 | 34 | 11 | TIGR | ||

| Mycobacterium sp. MCS | 38 | 11 | JGI | ||

| Mycobacterium sp. KMS | 38 | 12 | JGI | ||

| Mycobacterium sp. JLS | 50 | 16 | JGI | ||

| Mycobacterium flavescens PYR-GCK | 48 | 13 | UniProt | ||

| Mycobacterium vanbaalenii PYR-1 | 66 | 24 | UniProt | ||

| Nocardiaceae | Nocardia farcinica IFM 10152 | 36 | 12 | UniProt | |

| Frankineae | Acidothermaceae | Acidothermus cellulolyticus 11B | 0 | 0 | UniProt |

| Frankiaceae | Frankia sp. CcI3 | 0 | 0 | UniProt | |

| Frankia sp. EAN1pec | 0 | 0 | UniProt | ||

| Kineosporiaceae | Kineococcus radiotolerans SRS30216 | 0 | 0 | UniProt | |

| Micrococcineae | Brevibacteriaceae | Brevibacterium linens BL2 | 0 | 0 | JGI |

| Cellulomonadaceae | Tropheryma whipplei str. Twist | 0 | 0 | UniProt | |

| Tropheryma whipplei TW08/27 | 0 | 0 | UniProt | ||

| Intrasporangiaceae | Janibacter sp. HTCC2649 | 6 | 2 | NCBI | |

| Microbacteriaceae | Leifsonia xyli subsp.xyli str. CTCB07 | 0 | 0 | UniProt | |

| Micrococcaceae | Arthrobacter aurescens TC1 | 0 | 0 | UniProt | |

| Arthrobacter sp. FB24 | 0 | 0 | UniProt | ||

| Propionibacterineae | Nocardioidaceae | Nocardioides sp. JS614 | 12 | 3 | UniProt |

| Propionibacteriaceae | Propionibacterium acnes KPA171202 | 0 | 0 | UniProt | |

| Pseudonocardineae | Pseudonocardiaceae | Amycolatopsis mediterranei d | 6 | 2 | Pfam |

| Streptomycineae | Streptomycetaceae | Streptomyces avermitilis MA-4680 | 6 | 2 | UniProt |

| Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) | 6 | 2 | UniProt | ||

| Streptosporangineae | Nocardiopsaceae | Thermobifida fusca YX | 0 | 0 | UniProt |

a Taxonomy from Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology [107]

b Number of proteins classified as PF02470

c Number of proteins classified as PF02405

d Incomplete genome, EMBL Accession AF040570

Examination of the genomic location of the Mce and DUF140 homologs revealed that the mce genes were almost always found clustered in groups of six, located downstream from a pair of DUF140 genes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the organization of mce loci in Actinomycetales genomes. Genes encoding proteins belonging to Pfam family PF02470 (Mce) are depicted as green boxes, and to family PF02405 (DUF140) as blue boxes. Dashes indicate gaps in gene numbering.

Identification of mce-like operons in Gram-negative bacteria

A 98 amino acid sub-region of Mce family proteins, termed the 'Mce-like' domain (PF02470), is widely distributed in Gram-negative bacteria and has also been found encoded in plant genomes. No Mce-like domains have been identified in any Archeael or low GC-content Gram-positive bacterial genomes.

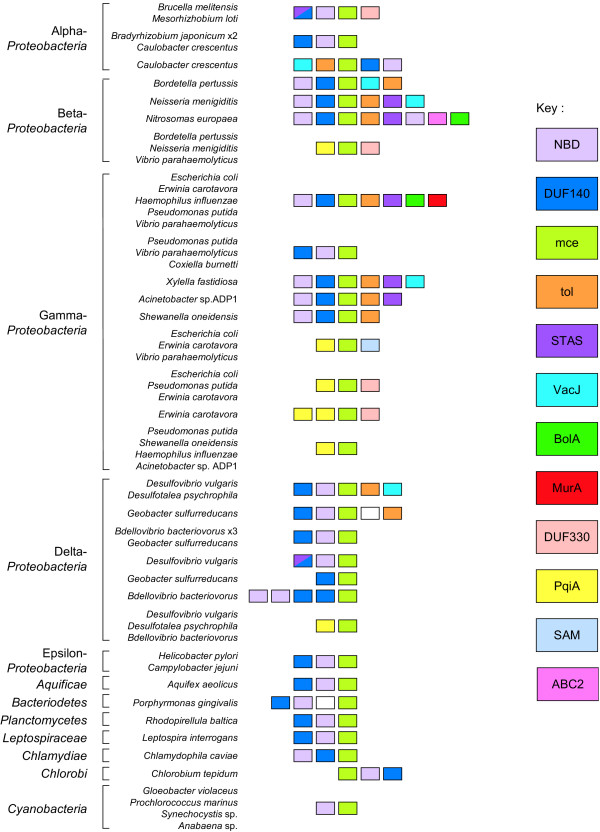

Genes with related functions are frequently encoded within operons and thus found clustered in the genomes of prokaryotes [22]. We investigated the gene neighborhoods of selected mce-like genes with the aim of obtaining clues regarding the biological role of proteins of this family (Figure 3). The Mce-like proteins in Gram-negative bacteria were frequently found clustered in the genome with a DUF140 family protein and an ATPase homolog (IPR003439) in an arrangement typical of an ABC transporter system [11]. The three components were found encoded in any order and in some instances either the DUF140 or ATPase homolog was duplicated. In a number of γ-Proteobacteria the ATPase-DUF140-Mce cluster was encoded in a conserved genomic region that included a Tol protein (IPR008869), a STAS domain protein (IPR002645) and MurA(IPR005750), the product of which catalyses the first step of murein biosynthesis. Like Mce domains, Tol proteins have homology to SBPs [29]; the presence of SBPs indicates that these operons encode substrate uptake transporters. Aravind and Koonin suggested that the nucleotide-binding activity of STAS domains, found in sulfate transporters, could regulate uptake in response to intracellular ATP or GTP concentrations [30]. Several DUF140 proteins that are N-terminally fused to STAS domains have been identified [31], implying a functional linkage between these two proteins in the mce operons [21]. The Mce transporter clusters were also frequently found associated with homologs of a surface-exposed lipoprotein VacJ (IPR007428), and the morpho-protein BolA (IPR002634).

Figure 3.

Conserved proteins encoded in the neighborhood of mce genes in Gram-negative bacteria. Coloring reflects conserved domains identified in the key. Protein families shown are: NBD, an ABC transporter ATPase (IPR003439); DUF140 (IPR003453); Mce (IPR003399); Tol, a Ttg2 toluene tolerance protein (IPR008869); STAS, a domain found in sulfate transporters and anti-sigma factor antagonists (IPR002645); VacJ, a lipoprotein of unknown function (IPR007428); BolA, a possible regulator induced by stress (IPR002634); MurA, UDP-N-acetylglucosamine-1-carboxyvinyltransferase (IPR005750); DUF330 (IPR005586); PqiA, an integral membrane protein inducible by superoxide generators (IPR007498); SAM, an S-adenosyl methionine binding methyltransferase (IPR000051); and ABC2, an ABC-2 type permease (IPR013525).

The Mce homologs in these putative transporter operons each contain a single 98 amino acid Mce-like domain. Many proteobacterial genomes additionally contain Mce homologs, sometimes annotated as PqiB, that contain 2–7 copies of the Mce-like domain and are usually associated with a PqiA family protein (IPR007498) of unknown function. The E. coli pqiAB operon is induced by treatment with the model superoxide generator, paraquat [32].

Mce-associated ATPases

Since ABC transporters absolutely require an ATPase to provide the energy required for substrate translocation, the genes neighboring the Actinomycetales mce operons were inspected for ATPase homologs (IPR003439). Although none of the mycobacterial mce operons neighbors an ATPase, a candidate gene was identified immediately upstream of a single mce operon in the genome of every non-mycobacterial Actinomycetales species that possesses mce genes (Table 2). BLASTP analyses demonstrated that the corresponding protein sequences were reciprocal best hits with the mce-linked ATPases in Gram-negative bacteria, indicating orthology [24]. A phylogenetic analysis of ABC transporter ATPases reported by Dassa and Bouige groups these Actinomycetales and Gram-negative bacterial ATPases into a family termed Mkl [8].

Table 2.

Actinomycetales mce-linked ATPases and mycobacterial orthologs

| Organism | ATPase |

| Amycolatopsis mediterranei | TrEMBL: Q7BUF5 |

| Janibacter sp. HTCC2649 | JNB_08429 |

| Nocardia farcinica | nfa51100 |

| Nocardioides sp. JS614 | NocaDRAFT_4321 |

| Streptomyces avermitilis | SAV5902 |

| Streptomyces coelicolor | SCO2422 |

| Mycobacterium bovis | Mb0674 |

| Mycobacterium flavescens | MflvDRAFT_3283 |

| Mycobacterium leprae | ML1892 |

| Mycobacterium paratuberculosis | MAP4129 |

| Mycobacterium smegmatis | MSMEG1359 |

| Mycobacterium sp. JLS | MjlsDRAFT_1757 |

| Mycobacterium sp. KMS | MkmsDRAFT_1059 |

| Mycobacterium sp. MCS | MmcsDRAFT_0968 |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis CDC1551 | MT0684 |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv | Rv0655 |

| Mycobacterium vanbaalenii | MvanDRAFT_5200 |

The sequences of the N. farcinica and Streptomyces mce-linked ATPases (nfa51100, SAV5902 and SCO2422) were used as BLASTP queries in order to identify additional Mkl-like ATPases. The best hits from each of the completed Actinomycetales genomes (Table 1) were retrieved for further evaluation. Phylogenetic analysis of the protein sequences revealed that each Mycobacterium species contained a single ATPase that clustered with the Mkl family, providing strong evidence of orthology (Figure 4, Table 2). In addition, a paralog was identified in the N. farcinica genome (nfa20200); this ORF is annotated in The Institute of Genome Research (TIGR) database as MetN, a D-methionine ABC transporter ATPase, but it does not cluster with other putative MetN orthologs (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree showing relationship between mce-linked ATPases and mycobacterial orthologs. ATPases encoded within mce operons in Actinomycetales species are colored blue; those in Gram-negative bacterial mce operons are colored green. The sequences most similar to nfa51100, SAV5902 and SCO2422 (indicated in bold), in the Actinomycetales genomes listed in Table 1, were identified by BLASTP searches and included in the tree. All of the best hits from mycobacterial species cluster within the Mkl family and are colored red. For comparison, sequences of all M. tuberculosis H37Rv ATPases of ABC uptake transporters were included [20]. All of the top hits from Actinomycetales that do not possess mce operons are rooted among these non-mce-linked ATPases, as are all of the second hits from mycobacterial species. ORFs are designated by (UniProt gene name | protein name).

Comparison of the most closely related ORFs in other Actinomycetales revealed that only those genomes that contained mce operons possessed an orthologous ATPase (Figure 4). Congruency of the phylogenetic profiles of the Mkl ATPases with YrbE and Mce proteins provides further evidence of functional association [23].

Each of the mce-linked ATPases and mycobacterial orthologs contain the conserved Walker A and B motifs required for ATP binding, as well as the ABC transporter family signature (LSGGQ) with no more than one mismatch [16,33]. In a published analysis of M. tuberculosis ABC transporters, the putative Mce ATPase, Rv0655, segregated with importers but did not fall into any of the previously described families with known substrates [20]. Similarly, in a more expansive study, the Mkl family ATPases fell into the SBP-dependent importer clade, but clustered separately from those with established specificity [8].

The mycobacterial Mkl ATPases and nfa20200 and are not genomically located near any other ABC transporter components and appear to be transcriptionally-isolated. The M. leprae ortholog is located adjacent to RNA polymerase rpo genes leading to speculation that this ATPase was involved in ribonucleotide uptake [34]. Consequently, Mkl ATPases are sometimes annotated as ribonucleotide uptake systems.

The Mce proteins

Comparison of the amino acid sequences of the Mce proteins encoded in the genomes of Mycobacterium bovis and the M. tuberculosis strains H37Rv, CDC1551 and 210, revealed that each of the M. tuberculosis genomes contained 24 Mce ORFs, whilst, as noted previously, the mce3 operon is deleted in M. bovis [35]. A number of genes were found to contain frameshift mutations: mce1F in strain 210; mce2B in strains H37Rv and CDC1551; mce2C in strain CDC1551; and mce2D and mce2E in M. bovis. The truncated ORFs thus conspicuously clustered within the mce2 operon.

A non-redundant set of Mce proteins from the genomes of M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, M. leprae, Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis (M. paratuberculosis), Mycobacterium smegmatis, N. farcinica, S. coelicolor and S. avermilitis were selected for further analysis. Examination of the genomic regions of partial operons revealed the presence of several additional putative Mce homologs that were included in this analysis (Table 3).

Table 3.

Classification of Actinomycetales yrbE and mce genes a

| Prefix b | yrbE1A | yrbE1B | mce1A | mce1B | mce1C | mce1D | mce1E | mce1F |

| Rv | 0167 | 0168 | 0169 | 0170 | 0171 | 0172 | 0173 | 0174 |

| MT | 0176 | 0177rc | 0178 | 0179 | 0180 | 0181 | 0182 | 0183 |

| Mb | 0173 | 0174 | 0175 | 0176 | 0177 | 0178 | 0179 | 0180 |

| ML | 2587 | 2588 | 2589 | 2590 | 2591 | 2592 | 2593 | 2594 |

| MAP | 3602 | 3603 | 3604 | 3605 | 3606 | 3607 | 3608 | 3609 |

| MSMEG | 0126 | 0127 | 0128 | 0129 | 0130 | 0131 | 0132 | 0133 |

| yrbE2A | yrbE2B | mce2A | mce2B | mce2C | mce2D | mce2E | mce2F | |

| Rv | 0587 | 0588 | 0589 | 0590 | 0591 | 0592 | 0593 | 0594 |

| MT | 0616 | 0617 | 0618 | 0619 | 0621 | 0622 | 0623 | 0624 |

| Mb | 0602 | 0603 | 0604 | 0605 | 0606 | 0607 | 0609 | 0610 |

| MAP | 4082 | 4083 | 4084 | 4085 | 4086 | 4087 | 4088 | 4089 |

| yrbE3A | yrbE3B | mce3A | mce3B | mce3C | mce3D | mce3E | mce3F | |

| Rv | 1964 | 1965 | 1966 | 1967 | 1968 | 1969 | 1970 | 1971 |

| MT | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

| Mb | 1999 | |||||||

| MAP | 2117c | 2117c.1d | 2116c | 2115c | 2114c | 2113c | 2112c | 2111c |

| MSMEG | 0335 | 0336e | 0337 | 0338 | 0339 | 0340 | 0341 | 0342 |

| yrbE4A | yrbE4B | mce4A | mce4B | mce4C | mce4D | mce4E | mce4F | |

| Rv | 3451c | 3450c | 3499c | 3498c | 3497c | 3496c | 3495c | 3494c |

| MT | 3605 | 3604 | 3603 | 3602 | 3601 | 3600 | 3599 | 3598 |

| Mb | 3531c | 3530c | 3529c | 3528c | 3527c | 3526c | 3525c | 3524c |

| MAP | 0562 | 0563 | 0564 | 0565 | 0566 | 0567 | 0568 | 0569 |

| MSMEG | 5861 | 5860 | 5859.3e | 5859.2e | 5859.1e | 5859 | 5858 | 5857.1e |

| nfa | 5350 | 5360 | 5370 | 5380 | 5390 | 5400 | 5410 | 5420 |

| yrbE5A | yrbE5B | mce5A | mce5B | mce5C | mce5D | mce5E | mce5F | |

| MAP f | 0757 | 0758 | 0759 | 0760 | 0761 | 0762/3g | 0764 | 0765 |

| MAP | 2189 | 2190 | 2191 | 2192 | 2193h | 2194 | ||

| MSMEG | 2855 | 2856 | 2857 | 2858 | 2859 | 2860 | 2861 | 2862 |

| MSMEG f | 4785 | 4784 | 4783 | 4782 | mei | 4777 | 4776 | 4775 |

| yrbE6A | yrbE6B | mce6A | mce6B | mce6C | mce6D | mce6E | mce6F | |

| nfa | 51090 | 51080 | 51070 | 51060 | 51050 | 51040 | 51030 | 51020 |

| SCO | 5901 | 5900 | 5899 | 5898 | 5897 | 5896 | 5895 | 5894 |

| SAV | 2421 | 2420 | 2419 | 2418 | 2417 | 2416 | 2415 | 2514 |

| yrbE7A | yrbE7B | mce7A | mce7B | mce7C | mce7D | mce7E | mce7F | |

| MAP j | mei | 0107 | 0108 | 0109 | 0110 | 0111 | 0112 | 0113 |

| MAP | 1849 | 1850 | 1851 | 1852 | 1853 | 1854 | 1855 | 1856 |

| MSMEG j | 1131 | 1132 | 1133 | 1134 | 1135 | 1136 | 1137 | 1138 |

| nfa | 50540 | 50530 | 50520 | 50510 | 50500 | 50490 | 50480 | 50470 |

| nfa | 56330 | 56320 | 56310 | 56300 | 56290 | 56280 | 56270 | 56260 |

| yrbE8A | yrbE8B | mce8A | mce8B | mce8C | mce8D | mce8E | mce8F | |

| nfa | 11130 | 11140 | 11150 | 11160 | 11170 | 11180 | 11190 | 11200 |

| nfa | 29780 | 29770 | 29760h | 29750 | 29740 | 29730 | 29720 | 29710 |

a Operons mce1-4 designated as in TubercuList; mce5-8 designated herein. Gene names in organisms other than M. tuberculosis do not correspond to those given in genome annotation.

b Organism specific gene number prefix: Rv, M. tuberculosis H37Rv; MT, M. tuberculosis CDC1551; Mb, M. bovis; ML, M. leprae; MAP, M. paratuberculosis; MSMEG, M. smegmatis; nfa, N. farcinica; SCO, S. coelicolor; SAV, S. avermitilis.

c Orthologous sequence present, but ORF annotated in reverse direction.

d Orthologous sequence present, but not annotated. ORF extends ~400 bp at 5'end.

e Orthologous sequence present, but not annotated.

f Orthology inferred from synteny.

g Contains frameshift mutation, resulting in two ORFs.

h Not a member of IPR003399 or IPR005693.

i Insertion of mobile element.

j Orthology inferred from synteny.

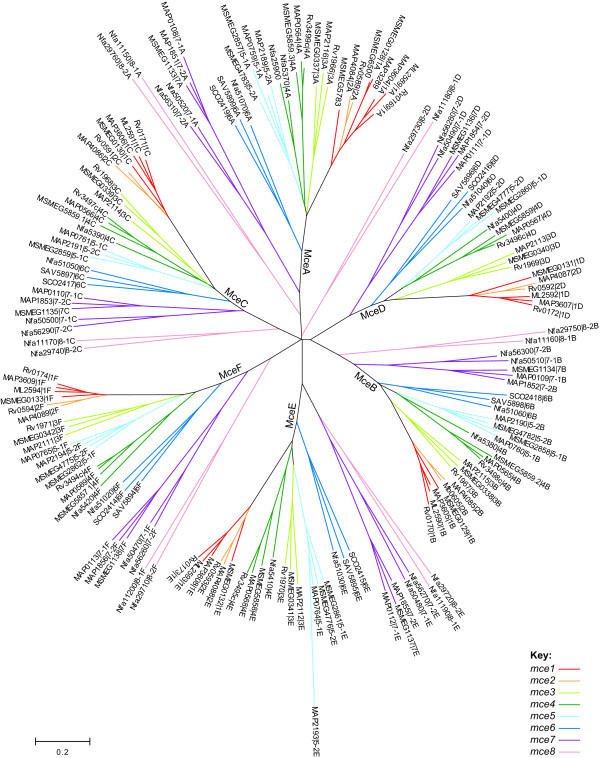

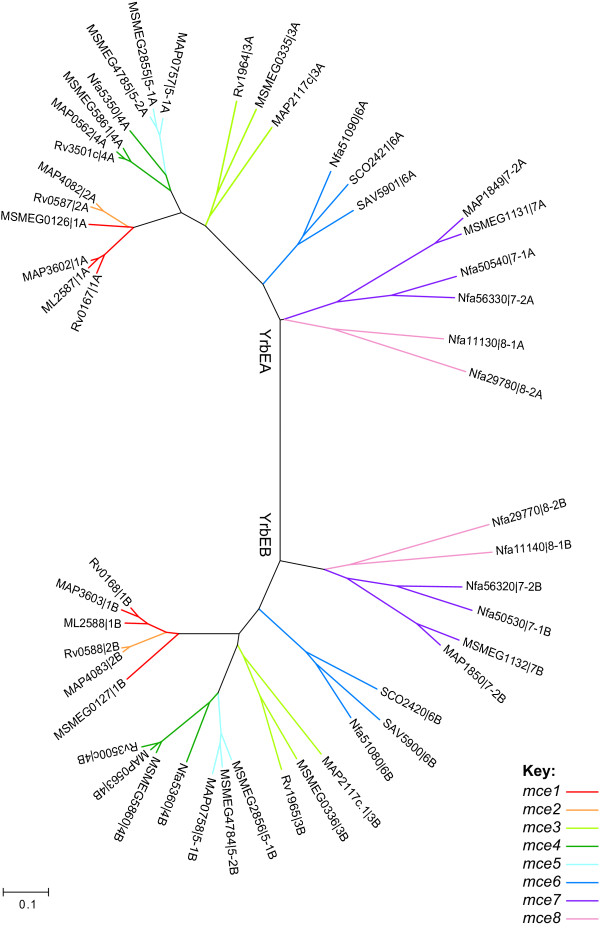

Multiple alignment and phylogenetic analysis of the Mce homologs revealed six distinct branches, which corresponded exactly to the encoding genes in the respective operons (that is mceA-F; Figure 5). Within each of the six major branches, the clustering of sequences was essentially the same. This pattern indicates that each mce gene cluster duplicated from an ancestral operon that contained six mce genes and that no shuffling between or within operons has occurred.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic tree of Actinomycetales Mce proteins. A non-redundant set of Mce protein sequences were aligned and an unrooted neighbor-joining tree was computed by MEGA. Coloring corresponds to the classification scheme specified in Table 3. ORFs are designated by [gene locus name | operon number (1–8) and gene position (A-F)]. Where operon orthology cannot be inferred, operons are designated: -1, -2.

We have classified the operons as mce1-8 according to the clustering observed (Table 3). The mce1 and mce2 operons are the most closely related and duplication may have occurred after divergence of the fast- and slow-growing mycobacteria, since M. smegmatis contains a single copy. Although the orthology of the M. smegmatis operon cannot be deduced from the phylogenetic tree, we infer from synteny that it is orthologous to the M. tuberculosis mce1 operon. Thus, mce1 is the sole operon that is found in all, and in only, the Mycobacterium species examined. The Streptomyces operons fall into a cluster, termed mce6, that does not contain any mycobacterial orthologs, but is found in N. farcinica. The Mkl-like ATPase is located upstream of yrbEA6 in all three of these operons. In several cases operon orthology could not be deduced from the branching pattern observed, presumably due to recent duplication events. Thus, it appears that M. paratuberculosis and M. smegmatis possess two copies of the mce5 operon; M. paratuberculosis and N. farcinica have two copies of the mce7 operon; and N. farcinica has two copies of the mce8 operon. The M. paratuberculosis Mce5E protein (MAP2193) seems to have diverged significantly from its paralog (MAP0764); examination of the encoding sequences revealed that this is a consequence of a 40bp deletion, which results in a frameshift of the N-terminal 120 amino acids.

One and two extra copies of Mce1A were found in M. paratuberculosis (MAP3289) and M. smegmatis (MSMEG5783, MSMEG6500), respectively; whilst N. farcinica contained a second copy of Mce4A (nfa25900). Each of the encoding genes appeared to be transciptionally isolated, with the exception of MSMEG5783, which is located within a four-gene operon that includes pyridoxamine 5-phosphate oxidase and a putative lipoprotein.

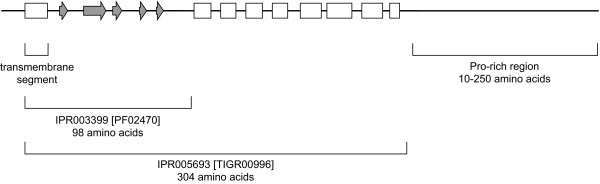

Secondary structure predictions, through the JPred server, revealed the consensus structure of the conserved Pfam region folded into five β-strands; the central region of Actinomycetales Mce proteins, included in the conserved TIGRFAM region, contains eight α-helices. The C-terminal region varies in length from 10–250 amino acids, has predicted low complexity and is rich in proline residues (Figure 6). Length is not conserved within the six homologous families, with the exception of the MceB proteins in which the C-terminal region is 30–50 amino acids in all cases. On average the MceA and MceF proteins are the longest. An RGD motif was identified in the C-terminal tail of 16 (of 27) MceE sequences. This motif is known to bind integrins, as well as C2 domains [36,37].

Figure 6.

Illustration of conserved regions and predicted secondary structure of Actinomycetales Mce proteins. Six separate alignments of the Mce proteins (A-F) listed in Table 3 were submitted to JPred and the consensus secondary structure prediction estimated manually. White boxes represent α-helices and grey arrows β-strands. The C-terminal proline-rich region had low complexity and varied in length from 10–250 amino acids. Signal sequences were identified by SignalP and lipid attachment sites matched the ProSite motif PS00013.

Each of the Mce proteins contained a hydrophobic stretch at the N-terminus, likely to be a transmembrane helix. Using a neural network trained on Gram-positive bacteria the program SignalP predicted a signal peptide cleavage site for 98 of 161 of these proteins [38]. There was no correlation between prediction of secretion and Mce-type (A-F) or bacterial species. Although the Mce anchor regions frequently contained a pair of arginine residues, characteristic of Twin-arginine transporter (Tat) motifs, few (12 of 161) are recognized as Tat substrates [39]. A lipoprotein attachment site (PS00013) was present in 22 of 27 MceE proteins. The highly conserved operon structure containing six mce genes suggests that they associate to form a heteromeric complex [22,40], which is therefore likely to remain tethered to the cell membrane even if some proteins are cleaved. Indeed, Mce1A-1F have been shown to localize to the cell envelope of M. tuberculosis [4].

The YrbE proteins

Unlike the Mce proteins, the amino acid sequences of YrbE orthologs in the M. tuberculosis strains H37Rv, CDC1551 and 210, as well as M. bovis, were found to be >99.5% identical in all cases. The sequences of the YrbE proteins associated with the mce gene clusters of M. tuberculosis, M. leprae, M. paratuberculosis, M. smegmatis, N. farcinica, S. coelicolor and S. avermilitis were selected for further analysis. In several cases the ORF downstream of yrbEA was either not annotated or annotated in the reverse direction; however, translation of the genomic sequence revealed a YrbEB homolog encoded in the expected direction (Table 3).

Phylogenetic analysis showed deep branching between the YrbEA and YrbEB sequences (Figure 7). Within each clade the clustering of sequences was almost identical demonstrating that the yrbEA-yrbEB genes have evolved as a pair. The clustering was comparable to that seen in the Mce protein tree, with members of the mce1/2 and mce3 to mce8 operons easily distinguishable. Thus, it appears that all of the operons examined evolved from a common ancestral eight-gene cluster without shuffling of genes within or between operons.

Figure 7.

Phylogenetic tree of Actinomycetales YrbE proteins. A non-redundant set of YrbE protein sequences were aligned and an unrooted neighbor-joining tree was computed by MEGA. Coloring corresponds to the classification scheme specified in Table 3. ORFs are designated by [gene locus name | operon number (1–8) and gene position (A, B)]. Where operon orthology cannot be inferred, operons are designated: -1, -2.

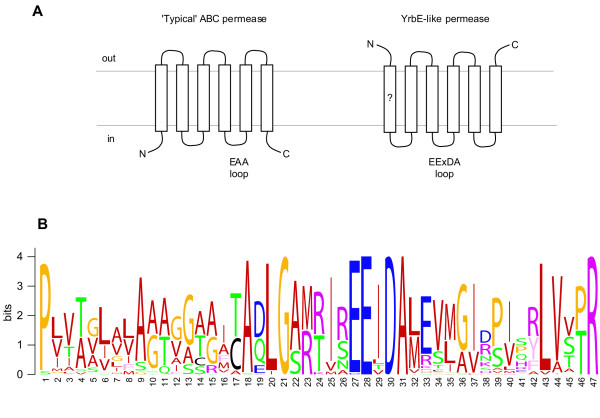

ABC permeases typically contain six transmembrane segments with the C-terminus located on the cytoplasmic side of the membrane [11]. The consensus TMHMM-predicted structure of Actinomycetales YrbE homologs found in mce operons suggests the presence of five or six transmembrane helices with the C-terminus outside (Figure 8a). The presence of the N-terminal transmembrane helix was equivocal, and therefore the N-terminus may be cytoplasmic or outside. Further topological predictions using the programs HMMTOP and TopPred confirmed this model, but were unable to verify or refute the existence of the N-terminal transmembrane segment.

Figure 8.

Predicted topology and conserved sequence motif of Actinomycetales YrbE proteins. (A) The consensus topology prediction of Actinomycetales YrbE proteins analysis is shown compared to that of a typical ABC permease [42]. (B) WebLogo illustration of the conserved YrbE EExDA sequence motif identified through MEME analysis.

Dassa and colleagues [41,42] have described a highly-conserved sequence, the EAA motif, in the final cytoplasmic loop of some SBP-dependent ABC permeases that is proposed to interact with the cognate ATPase [43]. Examination of the multiple alignment of YrbE proteins revealed a conserved sequence motif located in the penultimate cytoplasmic loop. The consensus deduced from 50 Actinomycetales YrbEA and YrbEB sequences is shown in Figure 8b. Alignment of Gram-negative bacterial DUF140 proteins revealed that this region was highly conserved in all family members. The consensus sequence we have deduced does not appear to be homologous to the published motifs, but does contain the common invariant glycine residue and is predicted to adopt the typical α-helical structure [42]. The consensus 47 amino acid YrbE sequence, that we have termed the EExDA motif, was able to specifically retrieve Actinomycetales and Gram-negative DUF140 proteins from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) microbial proteomes database.

In one case (Rhodopirellula baltica, RB3287) a DUF140 domain is fused to an ABC ATPase domain providing evidence that the function of DUF140 proteins requires ATP hydrolysis [21].

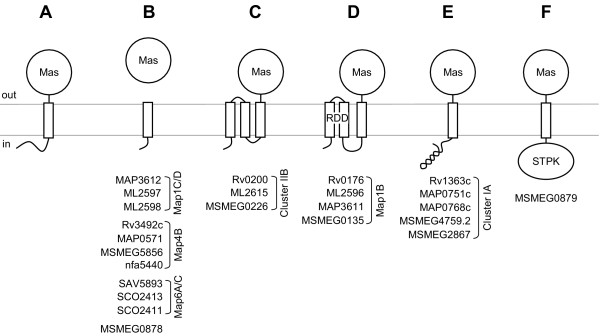

The Mas proteins

The four genes downstream of the M. tuberculosis mce1 operon, as well as two each downstream of the mce3 and mce4 operons, are annotated in TubercuList [44] as 'conserved mce-associated proteins' (herein termed Mas). The mce1 operon transcript has been empirically demonstrated to include the associated mas genes (Rv0175-78) [45]. Examination of a multiple alignment of the protein sequences revealed that they were not conserved along their entire length but shared a similar C-terminal region of approximately 160 amino acids. Pairwise sequence identity scores, generated by ClustalX, for the conserved region ranged from 12 to 25%.

To determine whether homologous domains were present in other genomes, we used each of the eight Mas C-terminal sequences as a PSI-BLAST query against the NCBI non-redundant database. A total of 137 sequences were retrieved; of these, 124 sequences were hit by all eight query sequences, and all 137 were hit by more than two queries. The proteins identified belonged to six genera: Amycolatopsis, Janibacter, Mycobacterium, Nocardia, Nocardiodes and Streptomyces. Thus, the phylogenetic profile for the putative Mas homologs in Actinomycetales genera exactly matches that of the Mce, DUF140 and Mkl proteins. Mas homologs in the M. smegmatis genome, which was not covered by the NCBI database, were identified by exhaustive BLAST querying of the TIGR proteome. Nineteen putative Mas homologs were thus identified (P < 0.00001).

Sequences of the putative Mas domain containing proteins from M. tuberculosis, M. leprae, M. paratuberculosis, M. smegmatis, N. farcinica, S. avermitilis and S. coelicolor were selected for further analysis. This resulted in a set of 66 sequences (including one hybrid sequence, MAP2107/9c, that has been disrupted by a transposase).

The Mas domain genes were typically found in pairs (58 of 66) and the majority (43 of 66) were encoded downstream of, and in the same direction, as mce genes (Table 4). Putative orthologs of each of the eight M. tuberculosis mce operon-associated mas genes were identified in the corresponding positions of those genomes carrying orthologous operons. Each of the mce7 operons had a single Mas protein encoded downstream. The mce6 operons of N. farcinica and S. avermilitis contained two mas genes, while the corresponding S. coelicolor operon carried four. In M. paratuberculosis, a pair of mas homologs was located in the regions both upstream and downstream of the mce5 operon, but transcribed from the opposite strand (MAP0750-51c, MAP0767-68c). The 23 non-mce operon-associated Mas homologs were generally located in pairs in isolated operons. An exception was Rv2390c, which TIGR predicts is part of a three-gene operon including a resuscitation promoting factor (rpfD, Rv2389c) and an Fe-S enzyme involved in porphyrin biosynthesis (hemN, Rv2388c).

Table 4.

Mas Homologs in Selected Actinomycetales Genomesab

| Rv | ML | MAP | MSMEG | nfa | SAV | SCO | |

| Mas1 A | 0175 (213) | 2595 (182) | 3610 (213) | 0134 (202) | |||

| B | 0176 (322) | 2596 (325) | 3611 (323) | 0135 (288) | |||

| C | 0177 (184) | 2597 (184) | 3612 (184) | 0136 (182) | |||

| D | 0178 (244) | 2598 (184) | 3613 (252) | 0137 (296) | |||

| Mas3 A | 1972 (191) | 2110c (203) | 0343 (200) | ||||

| B | 1973 (160) | 2109/7cc | 0344 (202) | ||||

| Mas4 A | 3493c (242) | 0570 (243) | 5857 (233) | 5430 (315) | |||

| B | 3492c (160) | 0571 (164) | 5856 (161) | 5440 (162) | |||

| Mas6 A | 51010 (248) | 5893 (177) | 2413 (170) | ||||

| B | 51000 (274) | 5892 (272) | 2412 (219) | ||||

| C | 2411 (184) | ||||||

| D | 2410 (253) | ||||||

| Mas7-1 A | 0114 (198) | 1139 (230) | 50460 (246) | ||||

| Mas7-2 A | 1857 (227) | 56250 (321) | |||||

| ClusterI A | 1363c (261) | 0751c (295) | 4759.2 (303) | ||||

| B | 1362c (220) | 0750c (187) | 4759 (200) | ||||

| A | 0768c (298) | 2867 (190) | |||||

| B | 0767c (224) | 2868 (218) | |||||

| ClusterII A | 0199 (219) | 2614 (229) | 0225 (206) | 6070 (197) | |||

| B | 0200 (229) | 2615 (224) | 0226 (229) | ||||

| A | 2390c (185) | 0090c (212) | |||||

| A | 0878 (167) | ||||||

| B | 0879 (496) | ||||||

| A | 5189 (231) | ||||||

| B | 5190 (192) | ||||||

a Organism specific gene number prefix: Rv, M. tuberculosis H37Rv; ML, M. leprae; MAP, M. paratuberculosis; MSMEG, M. smegmatis; nfa, N. farcinica; SCO, S. coelicolor; SAV, S. avermitilis.

b Each row contains putative orthologs. Length of protein in amino acids shown in parentheses.

c ORF is interrupted by a transposase, MAP2108.

The Mas region is not currently recognized as a conserved domain in the databases. However, within this region, InterPro recognized a lipocalin family motif (IPR002345) in Rv3492c, and a partial C2 domain signature (IPR000008) in Rv0199 and ML2614. Notably, the corresponding Pfam families (PF00061 and PF00168) did not include these sequences as members. Nonetheless, it may be worthy of mention that the lipocalin and C2 domains share a lipid-binding function, as well as an eight-stranded anti-parallel beta sandwich structure [46,47].

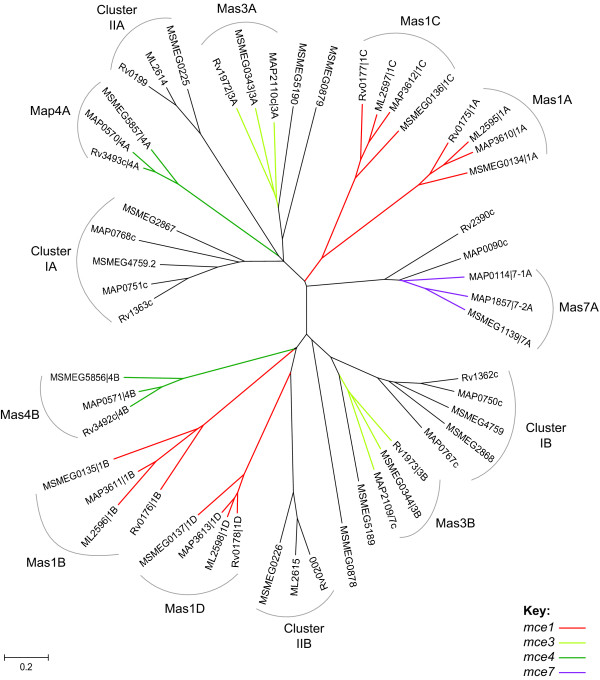

The majority of pairwise identity scores for the 66 Mas domains were 10–20%. This low level of sequence similarity resulted in multiple sequence alignments that were extremely sensitive to input parameters. Exclusion of the 13 non-mycobacterial sequences produced a much more robust alignment. A phylogenetic tree generated from this alignment is shown in Figure 9. Examination of the tree revealed that the Mas proteins encoded by the first and second genes in each pair formed phylogenetically distinct clusters. The Mas proteins encoded adjacent to mce operons were not separated from the non-mce associated Mas proteins. The M. leprae, M. paratuberculosis and M. smegmatis Mas proteins associated with the mce1, mce3 and mce4 operons are clearly orthologs of those in the corresponding genomic positions in M. tuberculosis. The mce7-associated Mas proteins also cluster together. Several pairs of non-mce associated Mas homologs were conserved between mycobacterial species (Figure 9; Cluster I and Cluster II).

Figure 9.

Phylogenetic tree of mycobacterial Mas domain sequences. The conserved Mas domains of mycobacterial proteins listed in Table 4 were aligned and an unrooted neighbor-joining tree was computed by MEGA. Coloring corresponds to the classification scheme specified in Table 3. ORFs are designated by [gene locus name | operon number (1, 3, 4, 7) and gene position (A-D)]. Where operon orthology cannot be inferred, operons are designated: -1, -2.

The mycobacterial mce-associated Mas orthologs have greater than 50% pairwise identity. In contrast, the Nocardia and Streptomyces mce6-associated Mas proteins are highly divergent (15–20% identity). This suggests that, unlike the mce and yrbE genes, the mas genes have either diverged more rapidly or were independently recruited to the operons.

Comparison of JPred secondary structure predictions for orthologous clusters revealed the consensus structure of the conserved domain was α1α2α3α4β1β2β3β4. Prediction of transmembrane helices indicated that all 66 protein sequences harbored a transmembrane segment located about 140–180 amino acids from the C-terminus and corresponding to α1. Topology prediction programs, TMHMM, HMMTOP and TopPred, suggested the C-terminus was extracellular for 41, 56 and 42, of the 66 submitted sequences, respectively. In no case did all three programs predict an extracellular N-terminus for a single protein. Thus, it seems likely that all N-termini are intracellular, while the C-terminal Mas domains are located on the external side of the cytoplasmic membrane.

The length of the N-terminal region preceding the Mas domain ranged from 7 to 325 amino acids. In the majority of proteins in which the N-terminal segment was less than 30 amino acids (11 of 16), α1 was predicted to be a signal peptide by SignalP (Figure 10). Consensus topology predictions indicated that the four Mas1B orthologs and three Cluster IIB proteins contained two N-terminal transmembrane helices (oriented in-out, out-in). In the Mas1B orthologs, the two N-terminal transmembrane segments correspond to an RDD domain (IPR010432). Examination of a multiple alignment revealed that although M. smegmatis Mas1B does not actually have the N-terminal signature RD residues, the Cluster IIB proteins do. It has been proposed that the RDD domain is involved in transport [31]; however, to date, no empirical evidence has been published to support this claim. In MSMEG0879 the 325 amino acid N-terminal region encodes a protein kinase domain (IPR000719) containing the Ser/Thr kinase active site motif (PS00108). Coiled-coils, which are known to mediate protein-protein interactions [48], were identified in the N-terminal region of each Cluster IA sequence by the Lupas COILS algorithm.

Figure 10.

Representative architectures of Mas domain-containing proteins. Membrane topology predictions for the 66 Mas proteins listed in Table 4 indicated that the conserved domain was located on the extracellular side of the cytoplasmic membrane. The Mas domain was predicted to remain anchored in the majority of proteins (A), but cleaved in eight (B). Three transmembrane segments were identified in seven proteins and four of these were classified as RDD domains (C, D). Five proteins contained an N-terminal coiled-coil region (E), and one, a serine-threonine protein kinase domain (STPK; F).

Discussion

In this study we sought to gain insight into the function of the M. tuberculosis mce operons using genome comparisons and bioinformatic methods.

The YrbE and Mce proteins, encoded by the M. tuberculosis mce operons, have homology to the permease and SBP components of ABC transporters, respectively [29]. However, sequence similarity within these protein families is notoriously low, and confirmation that the mce operons encode ABC importers has required identification of the necessary cognate ATPase. Dassa and Bouige [8] have proposed that Rv0655, an ATPase named Mkl, might supply this function and here we provide substantial evidence that this is indeed the case.

Firstly, Mkl orthologs are encoded immediately upstream of the mycobacterial-like mce operons in species of Nocardia, Janibacter, Nocardioides, Amycolatopsis and Streptomyces. Secondly, orthologs of Mkl are found in all, and in only, those Actinomycetales species that also contain Mce and DUF140 homologs. The presence of an intact mkl gene in the M. leprae genome, which has undergone extensive reductive evolution [49], is significant in this respect. Thirdly, in Gram-negative bacteria, operons containing DUF140 and mce homologs invariably include the orthologous mkl gene. Recently, Joshi et al. [7] observed that in competitive mouse infections an Rv0655 mutant was attenuated relative to wild-type M. tuberculosis, whereas an Rv0655-mce1 double mutant showed no attenuation relative to the mce1 mutant, providing evidence that Rv0655 and the Mce1 proteins are functionally linked. It is notable that in the Mycobacterium species examined, the mkl gene is located within the genomic region that encodes the majority of ribosomal proteins; this is generally the most conserved region in prokaryotic genomes and could facilitate high level expression of mkl [40].

It is widely accepted that the direction of substrate transport of ABC transporters can be predicted on the basis of ATPase homology [10]. In phylogenetic analyses, Mkl ATPases fall into the importer clade [8,20]; this prediction is consistent with the proposed role of Mce proteins as SBPs, which are found exclusively in substrate import systems.

The results of topology prediction indicated that the YrbE proteins contained five to six transmembrane segments, with the C-terminal five the most conserved and the C-terminus outside. In support of this model, the periplasmic location of the C-terminus of E. coli YrbE has been demonstrated empirically [50]. In general, ABC permeases show the highest level of sequence similarity over the C-terminal five transmembrane regions, and this is considered to be the minimal functional unit [11]. In compiled alignments of ABC permease sequences, the most conserved region localizes to the final cytoplasmic loop [42]. This motif, termed the EAA loop, likely interacts with the cognate ATPase [43]. A highly conserved motif, predicted to localize to the penultimate cytoplasmic loop, was identified in YrbE proteins from both Actinomycetales and Gram-negative bacteria. We propose that this motif, named the EExDA loop, serves as the site of interaction with the putative cognate Mkl ATPase, in a manner analogous to the EAA loop.

Conservation of the 'two yrbE plus six mce' operon structure suggests that these components comprise the functional unit of the canonical Actinomycetales Mce transporter [22,40]. We have found that mutation of either the yrbE1A, mce1A or mce1E genes of M. tuberculosis results in undetectable levels of all the Mce1 proteins, implying that these proteins are part of a hetero-octomeric complex and its formation is necessary for stability of the Mce proteins [4] (L. Morici, personal communication). It is interesting that many Proteobacteria contain membrane proteins with multiple Mce domains (PqiB proteins) that could potentially interact forming a quaternary structure analogous to the putative Acinomycetales Mce complex. The permease components of ABC transporters, that form a channel across the cytoplasmic membrane, are frequently heterodimers; however, although present in stoichiometric excess, SBPs are generally encoded by one or two genes [11]. The presence of six SBPs is, thus far, a unique characteristic of the Actinomycetales Mce transporters. Using computational methods, Pajon et al. [51] found that the β-sheet region of eight of the M. tuberculosis Mce proteins contained patterns typical of transmembrane β-strands and suggested that this region could promote penetration of the outer lipid layer. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that the Mce proteins are designed to form a channel that crosses this lipid bilayer. Chitale et al. [52] have previously shown that Mce1A is indeed exposed on the surface of M. tuberculosis.

Proteins encoded downstream of three of the four M. tuberculosis mce operons exhibit significant sequence homology. Similarity is confined to the 160 amino acid C-terminal region, we have termed the Mas domain, that is predicted to localize to the extracellular side of the cytoplasmic membrane. In each of the Actinomycetales genomes examined, Mas domain proteins were found linked to the majority of mce operons. Mas proteins show absolute phylogenetic congruency with Mkl, DUF140 and Mce proteins in the genomes of Actinomycetales, providing evidence that they are involved in Mce transporter function. Given that Mas domains are not found associated with all mce operons, their function may not always be strictly required or they may be shared between operons. The propensity of Mas homologs to be located in pairs suggests that they form heterodimers. Such an interaction would likely keep the predicted secreted Mas proteins tethered to the cell surface. The domain architectures of the Mas proteins suggest that the conserved domain plays an accessory ligand-binding role.

Several studies have shown that the γ-proteobacterial mce loci play a role in determination of structural properties of the cell envelope, which in pathogenic species affects invasive activity. In Pseudomonas putida, a transposon insertion within the DUF140-Mce-associated ttg2A ATPase (PP0958) renders the cells sensitive to toluene [53]. In addition to toluene degradation and efflux, toluene tolerance is known to be mediated by increased cell membrane rigidity resulting from changes in fatty acid and phospholipid composition [54]. In Shigella flexneri, mutations in the vpsABC locus (S_3453-51), encoding an ABC transporter with the ATPase-DUF140-Mce configuration, result in a defect in intercellular spread through epithelial cell monolayers, altered colony morphology, increased sensitivity to detergent lysis and hypersecretion of both Sec-dependent and TypeIII-dependent virulence proteins [55]. Carvalho et al. have reported that in Campylobacter isolates, presence of iamA, the ATPase gene of the mce operon (Cj1646-48), correlated with an invasive phenotype [56], although, this association remains controversial [57-59]. In Neisseria meningitidis the mce-like operon, gltT (NMB1966-64), belongs to the GdhR regulon, which is expressed at higher levels in invasive versus commensal isolates, and is particularly elevated in hypervirulent lineages [60].

Comparable function has been attributed to the M. tuberculosis mce1 operon. The prototypical Mce protein, M. tuberculosis Mce1A, conferred invasive ability upon E. coli and an M. bovis BCG mce1A mutant exhibited impaired invasion of epithelial cells [1,61]. Moreover, an M. tuberculosis mce1 operon mutant has been shown to have an overabundance of free mycolic acids in the outer lipid layer (S. Cantrell, personal communication), supporting the proposition that mce1 and related operons play a role in remodeling the cell envelope. The presence of mce operons in Gram-negative bacteria and Actinomycetales genera that possess a somewhat analogous outer lipid bilayer raises the possiblity that the mce operons are involved in maintenance of outer membrane integrity. However, their presence in other Actinomycetales with typical Gram-positive type cell envelopes appears to preclude this hypothesis. In addition, the absence of mce operons in Corynebacterium species indicates that their function is not essential for maintenance of an outer lipid bilayer.

Based on a stated similarity of the ATPase component to GluA of Corynebacterium glutamicum, Meidanis et al. [62] proposed that the Xylella fastidiosa mce-like operon (XF0421-19) encoded a glutamate importer. It was subsequently shown that a mutation within the homologous N. meningitidis gltT operon resulted in impaired glutamate-specific uptake at low sodium concentrations [63]. Glutamate is a prominent constituent of peptidoglycan; thus, disruption of its uptake in the proteobacterial mce operon mutants could perhaps account for the observed effect on cell envelope properties. Also relevant in this respect, is the conserved location of the peptidoglycan biosynthetic gene, murA, downstream of the Mce transporter genes in γ-Proteobacteria.

Homologs of the Mkl, Mce and DUF140 proteins have also been identified in plants [64]. The Arabidopsis homologs of DUF140 (TGD1, At1g19800) and Mce (TGD2, At3g20320) both localize to the inner plastid membrane, with the Mce domain located in the intra-membrane space. Lipid binding studies demonstrated that TGD1 specifically bound 1,2-diacyl-sn-glycerol 3-phosphate (phosphatidic acid). TGD1 and TGD2 mutants exhibited identical phenotypes consistent with disruption of transport of ER-derived phosphatidic acid into chloroplasts, suggesting the TGD proteins form part of a lipid translocator [65-67].

Orthologous ABC transporters are expected to be functionally equivalent [13-15], thus the proposal of both phosphatidic acid and glutamate as possible substrates of the Mce transporters is puzzling. It is noteworthy that in sequence analyses, by us and others, the Mkl-like ATPases are not closely related to GluA [8]. If the bacterial Mce homologs have phospholipid binding function, equivalent to TGD1, this might enable interaction with host cell membranes and explain the invasive phenotype associated with the mce loci. It is generally accepted that host-derived lipids are the primary source of carbon utilized by M. tuberculosis in vivo [68]; however no mechanism of lipid import has been identified. Thus it is enticing to hypothesize that the Mce transporters might perform this role. Inclusion of the fatty-acyl CoA synthetase, fadD5, in the mce1 operon and repression of the operon by a FadR-like regulator, lends some support to this conjecture [45].

The canonical eight-gene mce operon has undergone extensive proliferation and deletion events within certain Actinomycetales lineages, most notably in Mycobacterium and Nocardia species. The simplest explanation for the presence of multiple mce operons is that it facilitates elevated expression. However, evidence from transcriptional analyses of M. tuberculosis suggest that, at least in this organism, the operons are not co-regulated [69-72]; in addition, three of the four operons are associated with transcriptional regulators [45,73]. In competitive mouse infections, Sassetti and Rubin [6] found that an mce1 mutant exhibited a growth defect during the first 1–2 weeks of infection, whilst an mce4 mutant showed attenuation 3–4 weeks after inoculation. These observations support the proposition that the operons function at different stages of infection. Differential expression of the individual Mce transporters may reflect optimization for substrate uptake under differing conditions, such as in the low sodium intracellular environment; alternatively, they might have varying substrate specificities.

The number of mce operons in individual species appears to reflect the variety of environmental niches inhabited. Thus, the fast-growing, typically soil-dwelling, Mycobacterium species possess the greatest number, with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-degrading species, isolated from bioremediation sites, containing the most [74]. In contrast, the host-specialized, slow-growing pathogenic species possess fewer operons, and the obligate intracellular pathogen, M. leprae, encodes a single complete mce operon. A high degree of sequence similarity indicates that the mce1 operon duplicated to create mce2 relatively recently. In M. tuberculosis complex strains, mce frameshift mutations are found conspicuously in these two operons: of the five described in this paper, four are in mce2 and the fifth is in mce1. This pattern may reflect the functional divergence of the mce1 and mce2 operons.

With the exception of mycolic acids, the distribution of morphological and chemotaxonomic traits within the Actinomycetales is polyphyletic [75]. Given the incongruent taxonomic distribution of the mce operons and their proposed role in integrity of the cell envelope, it is pertinent to note that presence of mce operons does not correlate with type of peptidoglycan, menaquinones, phospholipids or fatty acids in the cell envelope [75,76]. In addition, there is no correlation with oxygen requirement, habitat or pathogenicity.

Conclusion

The available evidence suggests that the mce operons encode a novel subfamily of ABC transporter uptake systems comprised of DUF140 permease components, Mce-like substrate-binding proteins, and Mkl-type ATPase domains. Disruption of mce operons, in both Actinomycetales and Gram-negative bacteria, affects properties of the cell envelope and associated virulence phenotypes of pathogenic species. Empirical studies have implicated both glutamate and phosphatidic acid as substrates of mce-like transporters; thus, although the precise substrate specificity of the M. tuberculosis Mce transporters remains uncertain, we conclude that it is likely to be an organic acid precursor of cell envelope biogenesis.

Methods

Databases

Gene annotations and protein sequences were obtained from the publicly available databases: UniProt [77,78]; TIGR Comprehensive Microbial Resource (CMR) [79,80]; NCBI Microbial Genome Project [81]; Joint Genome Institute Microbial Genomics Database [82]; and TubercuList [44]. Sequences are referred to by the ordered locus name provided in these databases. Protein classification was informed by interrogation of conserved domain and motif databases: InterPro (IPR) [26,83], Pfam (PF) [27,31], TIGRFAM (TIGR) [28,79], and PROSITE (PS) [84,85]. The ABC transporter classification database, ABCISSE, was also consulted [29].

BLAST analyses

Sequence similarity searches were performed by BLASTP against complete microbial genome sequences deposited in the TIGR-CMR and NCBI Microbial Genome Project databases [79,81,86]. To determine whether the EExDA motif identified in YrbE proteins was uniquely characteristic of the DUF140 family, we performed a BLASTP search of NCBI Microbial Genome Project with the Actinomycetales YrbE consensus motif (PLVTGLALAGAGGAAITADLGARRIREEIDALEVMGIDPISRLVVPR) using the default parameters, except with no filter and expect threshold of 100. To identify homologs of the M. tuberculosis Mas domain, each of the eight sequences was used in a PSI-BLAST query against the NCBI non-redundant database [87]. We used an inclusion threshold of P < 10-5 and the scores were adjusted with composition-based statistics; these parameters resulted in convergence after 6–8 iterations.

Multiple alignment and phylogenetic analyses

Phylogenetic analyses were conducted using the MEGA version 3.1 suite of programs [88]. Multiple alignments were constructed by CLUSTAL-W using the Gonnet weight matrix and default gap penalties [89]. Unrooted trees were computed by the neighbor-joining method. The consensus tree, after 500 bootstrap replicates, was displayed graphically with Tree Explorer. In addition, CLUSTAL-W alignments were converted to PHYLIP format and trees computed by the maximum likelihood method implemented by PROML using default parameters [90]. In all cases this resulted in a tree with topology that was essentially the same as the neighbor-joining tree generated by MEGA. Percentage pairwise similarity scores were calculated by CLUSTAL-X [91].

Identification of conserved motifs

The MEME server was used to discover highly conserved sequence motifs within groups of homologous proteins [92,93]. Motifs were displayed graphically using WebLogo [94,95].

Secondary structure and topology prediction

Groups of aligned orthologs were submitted to JPred [96], a consensus secondary structure prediction server, that provides improved accuracy over single sequence prediction methods [97]. Comparison of predictions between orthologous clusters by visual inspection allowed estimation of the consensus structure for a homologous family. Coiled-coils were predicted using the Lupas COILS algorithm through the JPred server [98].

Protein sequences were analyzed by SignalP and TatP to identify Sec- and Tat-dependent signal sequences [38,39,99]. The reliability of prediction of transmembrane helices and topology of proteins increases when different methods are combined [100]. Hence, we submitted sequences to TMHMM [101,102], HMMTOP [103,104] and TopPred [105,106], and determined the consensus prediction by manual comparison.

Authors' contributions

NC conceived, designed and performed the study. LWR helped to interpret the data. NC drafted the manuscript; both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Owen Solberg and Sally Cantrell for useful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank S.C. and Lisa Morici for sharing unpublished data. This work was supported by grants from NIH (R21AI063350) and the Senior Scholar Award in Global Infectious Disease of the Ellison Medical Foundation.

Contributor Information

Nicola Casali, Email: ncasali@berkeley.edu.

Lee W Riley, Email: lwriley@berkeley.edu.

References

- Arruda S, Bomfim G, Knights R, Huima-Byron T, Riley LW. Cloning of an M. tuberculosis DNA fragment associated with entry and survival inside cells. Science. 1993;261:1454–1457. doi: 10.1126/science.8367727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon SV, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry CE, 3rd, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Krogh A, McLean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver K, Osborne J, Quail MA, Rajandream MA, Rogers J, Rutter S, Seeger K, Skelton J, Squares R, Squares S, Sulston JE, Taylor K, Whitehead S, Barrell BG. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekaia F, Gordon SV, Garnier T, Brosch R, Barrell BG, Cole ST. Analysis of the proteome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in silico. Tuber Lung Dis. 1999;79:329–342. doi: 10.1054/tuld.1999.0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimono N, Morici L, Casali N, Cantrell S, Sidders B, Ehrt S, Riley LW. Hypervirulent mutant of Mycobacterium tuberculosis resulting from disruption of the mce1 operon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15918–15923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2433882100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gioffre A, Infante E, Aguilar D, De la Paz Santangelo M, Klepp L, Amadio A, Meikle V, Etchechoury I, Romano MI, Cataldi A, Hernandez RP, Bigi F. Mutation in mce operons attenuates Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence. Microbes Infect. 2005;7:325–334. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassetti CM, Rubin EJ. Genetic requirements for mycobacterial survival during infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:12989–12994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2134250100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi SM, Pandey AK, Capite N, Fortune SM, Rubin EJ, Sassetti CM. Characterization of mycobacterial virulence genes through genetic interaction mapping. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11760–11765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603179103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dassa E, Bouige P. The ABC of ABCs: A phylogenetic and functional classification of ABC systems in living organisms. Res Microbiol. 2001;152:211–229. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(01)01194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Chandolia A, Chaudhry U, Brahmachari V, Bose M. Comparison of mammalian cell entry operons of mycobacteria: In silico analysis and expression profiling. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2005;43:185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.femsim.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saurin W, Hofnung M, Dassa E. Getting in or out: Early segregation between importers and exporters in the evolution of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters. J Mol Evol. 1999;48:22–41. doi: 10.1007/pl00006442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boos W, Eppler T. Prokaryotic binding protein-dependent ABC transporters. In: Winkelmann G, editor. Microbial Transport Systems. Weinheim, Germany , Wiley VCH; 2002. pp. 77–114. [Google Scholar]

- Ames GF, Liu CE, Joshi AK, Nikaido K. Liganded and unliganded receptors interact with equal affinity with the membrane complex of periplasmic permeases, a subfamily of traffic ATPases. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:14264–14270. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.24.14264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam R, Saier MH., Jr. Structural, functional, and evolutionary relationships among extracellular solute-binding receptors of bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:320–346. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.2.320-346.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saurin W, Dassa E. Sequence relationships between integral inner membrane proteins of binding protein-dependent transport systems: Evolution by recurrent gene duplications. Protein Sci. 1994;3:325–344. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuan G, Dassa E, Saurin W, Hofnung M, Saier MH., Jr. Phylogenetic analyses of the ATP-binding constituents of bacterial extracytoplasmic receptor-dependent ABC-type nutrient uptake permeases. Res Microbiol. 1995;146:271–278. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(96)81050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JE, Saraste M, Runswick MJ, Gay NJ. Distantly related sequences in the alpha- and beta-subunits of ATP synthase, myosin, kinases and other ATP-requiring enzymes and a common nucleotide binding fold. EMBO J. 1982;1:945–951. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames GF, Mimura CS, Holbrook SR, Shyamala V. Traffic ATPases: A superfamily of transport proteins operating from Escherichia coli to humans. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1992;65:1–47. doi: 10.1002/9780470123119.ch1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linton KJ, Higgins CF. The Escherichia coli ATP-binding cassette (ABC) proteins. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:5–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quentin Y, Fichant G, Denizot F. Inventory, assembly and analysis of Bacillus subtilis ABC transport systems. J Mol Biol. 1999;287:467–484. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braibant M, Gilot P, Content J. The ATP binding cassette (ABC) transport systems of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2000;24:449–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2000.tb00550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcotte EM, Pellegrini M, Ng HL, Rice DW, Yeates TO, Eisenberg D. Detecting protein function and protein-protein interactions from genome sequences. Science. 1999;285:751–753. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5428.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbeek R, Fonstein M, D'Souza M, Pusch GD, Maltsev N. The use of gene clusters to infer functional coupling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2896–2901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini M, Marcotte EM, Thompson MJ, Eisenberg D, Yeates TO. Assigning protein functions by comparative genome analysis: Protein phylogenetic profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4285–4288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusov RL, Koonin EV, Lipman DJ. A genomic perspective on protein families. Science. 1997;278:631–637. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanai I, DeLisi C. The society of genes: Networks of functional links between genes from comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 2002;3:research0064. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-11-research0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder NJ, Apweiler R, Attwood TK, Bairoch A, Bateman A, Binns D, Bradley P, Bork P, Bucher P, Cerutti L, Copley R, Courcelle E, Das U, Durbin R, Fleischmann W, Gough J, Haft D, Harte N, Hulo N, Kahn D, Kanapin A, Krestyaninova M, Lonsdale D, Lopez R, Letunic I, Madera M, Maslen J, McDowall J, Mitchell A, Nikolskaya AN, Orchard S, Pagni M, Ponting CP, Quevillon E, Selengut J, Sigrist CJA, Silventoinen V, Studholme DJ, Vaughan R, Wu CH. InterPro, progress and status in 2005. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D201–205. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn RD, Mistry J, Schuster-Bockler B, Griffiths-Jones S, Hollich V, Lassmann T, Moxon S, Marshall M, Khanna A, Durbin R, Eddy SR, Sonnhammer ELL, Bateman A. Pfam: Clans, web tools and services. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D247–251. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haft DH, Selengut JD, White O. The TIGRFAMs database of protein families. Nucl Acids Res. 2003;31:371–373. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ABCISSE: Database of ABC systems http://www.pasteur.fr/recherche/unites/pmtg/abc/database.iphtml

- Aravind L, Koonin EV. The STAS domain - A link between anion transporters and antisigma-factor antagonists. Curr Biol. 2000;10:R53–5. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfam http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Software/Pfam/

- Koh YS, Roe JH. Isolation of a novel paraquat-inducible (pqi) gene regulated by the soxRS locus in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2673–2678. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.10.2673-2678.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames GF, Mimura CS, Shyamala V. Bacterial periplasmic permeases belong to a family of transport proteins operating from Escherichia coli to humans: Traffic ATPases. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1990;6:429–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb04110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honore N, Bergh S, Chanteau S, Doucet-Populaire F, Eiglmeier K, Garnier T, Georges C, Launois P, Limpaiboon T, Newton S, Niang K, del Portillo P, Ramesh GR, Reddi P, Ridel PR, Sittisombut N, Wu-Hunter S, Cole ST. Nucleotide sequence of the first cosmid from the Mycobacterium leprae genome project: Structure and function of the Rif-Str regions. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:207–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zumarraga M, Bigi F, Alito A, Romano MI, Cataldi A. A 12.7 kb fragment of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome is not present in Mycobacterium bovis. Microbiology. 1999;145:893–897. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-4-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza SE, Ginsberg MH, Plow EF. Arginyl-glycyl-aspartic acid (RGD): A cell adhesion motif. Trends Biochem Sci. 1991;16:246–250. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90096-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoes I, Mueller EC, Otto A, Bur D, Cheung AY, Faro C, Pires E. Molecular analysis of the interaction between cardosin A and phospholipase Da: Identification of RGD/KGE sequences as binding motifs for C2 domains. FEBS Journal. 2005;272:5786–5798. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SignalP Server version 3.0 http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/

- TatP Server version 1.0 http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TatP/

- Wolf YI, Rogozin IB, Kondrashov AS, Koonin EV. Genome alignment, evolution of prokaryotic genome organization, and prediction of gene function using genomic context. Genome Res. 2001;11:356–372. doi: 10.1101/gr.gr-1619r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dassa E, Hofnung M. Sequence of gene malG in E. coli K12: Homologies between integral membrane components from binding protein-dependent transport systems. EMBO J. 1985;4:2287–2293. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03928.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saurin W, Koster W, Dassa E. Bacterial binding protein-dependent permeases: Characterization of distinctive signatures for functionally related integral cytoplasmic membrane proteins. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:993–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourez M, Hofnung M, Dassa E. Subunit interactions in ABC transporters: A conserved sequence in hydrophobic membrane proteins of periplasmic permeases defines an important site of interaction with the ATPase subunits. EMBO J. 1997;16:3066–3077. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.11.3066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TubercuList http://genolist.pasteur.fr/TubercuList/

- Casali N, White AM, Riley LW. Regulation of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis mce1 operon. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:441–449. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.2.441-449.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop RE. The bacterial lipocalins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1482:73–83. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(00)00138-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizo J, Sudhof TC. C2-domains: Structure and function of a universal Ca2+-binding domain. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15879–15882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.26.15879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupas A. Coiled coils: New structures and new functions. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:375–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole ST, Eiglmeier K, Parkhill J, James KD, Thomson NR, Wheeler PR, Honore N, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Mungall K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies RM, Devlin K, Duthoy S, Feltwell T, Fraser A, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Lacroix C, Maclean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver K, Quail MA, Rajandream MA, Rutherford KM, Rutter S, Seeger K, Simon S, Simmonds M, Skelton J, Squares R, Squares S, Stevens K, Taylor K, Whitehead S, Woodward JR, Barrell BG. Massive gene decay in the leprosy bacillus. Nature. 2001;409:1007–1011. doi: 10.1038/35059006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley DO, Rapp M, Granseth E, Melen K, Drew D, von Heijne G. Global topology analysis of the Escherichia coli inner membrane proteome. Science. 2005;308:1321–1323. doi: 10.1126/science.1109730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajon R, Yero D, Lage A, Llanes A, Borroto CJ. Computational identification of b-barrel outer-membrane proteins in Mycobacterium tuberculosis predicted proteomes as putative vaccine candidates. Tuberculosis. 2006;86:290–302. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitale S, Ehrt S, Kawamura I, Fujimura T, Shimono N, Anand N, Lu S, Cohen-Gould L, Riley LW. Recombinant Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein associated with mammalian cell entry. Cell Microbiol. 2001;3:247–254. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Lee S, Lee K, Lim D. Isolation and characterization of toluene-sensitive mutants from the toluene-resistant bacterium Pseudomonas putida GM73. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3692–3696. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.14.3692-3696.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos JL, Duque E, Rodriguez-Herva JJ, Godoy P, Haidour A, Reyes F, Fernandez-Barrero A. Mechanisms for solvent tolerance in bacteria. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3887–3890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.3887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong M, Gleason Y, Wyckoff EE, Payne SM. Identification of two Shigella flexneri chromosomal loci involved in intercellular spreading. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4700–4710. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4700-4710.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho AC, Ruiz-Palacios GM, Ramos-Cervantes P, Cervantes LE, Jiang X, Pickering LK. Molecular characterization of invasive and noninvasive Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:1353–1359. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.4.1353-1359.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozynek E, Dzierzanowska-Fangrat K, Jozwiak P, Popowski J, Korsak D, Dzierzanowska D. Prevalence of potential virulence markers in Polish Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolates obtained from hospitalized children and from chicken carcasses. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54:615–619. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45988-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller J, Schulze F, Muller W, Hanel I. PCR detection of virulence-associated genes in Campylobacter jejuni strains with differential ability to invade Caco-2 cells and to colonize the chick gut. Veterinary Microbiology. 2006;113:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mahmeed A, Senok AC, Ismaeel AY, Bindayna KM, Tabbara KS, Botta GA. Clinical relevance of virulence genes in Campylobacter jejuni isolates in Bahrain. J Med Microbiol. 2006;55:839–843. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46500-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagliarulo C, Salvatore P, De Vitis LR, Colicchio R, Monaco C, Tredici M, Tala A, Bardaro M, Lavitola A, Bruni CB, Alifano P. Regulation and differential expression of gdhA encoding NADP-specific glutamate dehydrogenase in Neisseria meningitidis clinical isolates. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:1757–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2003.03947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flesselles B, Anand NN, Remani J, Loosmore SM, Klein MH. Disruption of the mycobacterial cell entry gene of Mycobacterium bovis BCG results in a mutant that exhibits a reduced invasiveness for epithelial cells. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;177:237–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meidanis J, Braga MD, Verjovski-Almeida S. Whole-genome analysis of transporters in the plant pathogen Xylella fastidiosa. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2002;66:272–299. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.2.272-299.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]