Abstract

Physicians today are required to do more than ever before; skills that were unnecessary in the past are now “givens.” In order for physicians to keep patients well, help them manage chronic problems, and encourage them to adhere to medication regimens, a positive doctor/patient relationship is vital. Establishing patient rapport, obtaining patient trust, and allowing patients to tell their stories show respect and allow a healing partnership.

Patients often expect help with emotional as well as physical problems, so it is important to obtain as much information from patients as possible. The BATHE technique is a psychotherapeutic procedure and serves as a rough screening test for anxiety, depression, and situational stress disorders. The BATHE technique consists of 4 specific questions about the patient's background, affect, troubles, and handling of the current situation, followed by an empathic response; the procedure takes approximately 1 minute and must be practiced. Physicians may use the BATHE technique to connect meaningfully with patients, screen for mental health problems, and empower patients to handle many aspects of their life in a more constructive way.

The reality is that “American medicine, although undergoing evolution, now faces changes of a magnitude that has never before been encountered.”1(p1) In response to these changes, hospitals are vigorously involved in reinventing themselves. From separate and distinct entities of bricks and mortar, hospitals are now cooperating, merging, reorganizing, and even closing in the face of changes occurring in the world around them. The hospital has gone from a profit center in fee-for-service, indemnity medical practice to a cost center in capitated managed care. Containing costs has become the byword, and the industry is responding aggressively. “Bricks and mortar” are rapidly becoming systems of care where the “system” becomes effective and efficient or does not survive.

It has been a busy morning. That admission to the unit took a lot longer than I expected, and now I'm running behind for the continuity clinic. Why has the hospital gotten involved in all of this outpatient stuff anyhow? Things were so much easier when there were lots of house staff around to take on these responsibilities. But with the hospital downsizing and the residents being moved out into the community for more and more training, the service chiefs are stuck with filling the gap. The outpatient clinic is a good example. I understand why all of this is going on, but that doesn't make it any easier to deal with!

Physicians also have to rethink their roles, particularly those that are hospital-based. We are changing from the old paradigm, “I'm a doctor, I take care of sick people” to a new one, “I'm a doctor, I keep people well.” The transition is arduous and occasionally painful, but survival issues are at stake. Physicians are finding themselves in a situation in which they must acquire skills that were unnecessary in the past, but are “givens” in today's new health care arena.

Gee, this first patient's chart must be an inch thick. According to the nurse's notes, she has chest pain, abdominal pain, headaches, insomnia, and fatigue, all lasting many months. Well, at least the vital signs are normal, and outside of some mild obesity, there doesn't appear to be anything else too striking, at least at first glance at this chart. But even so, how can I evaluate all of these symptoms when I'm already running behind and the waiting room is full of people? Why wasn't I taught how to do this in medical school or in my residency program?

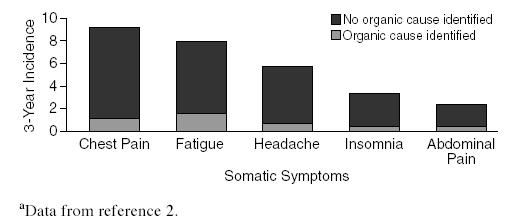

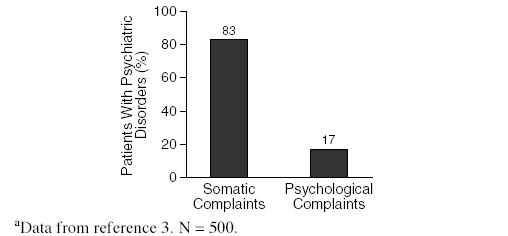

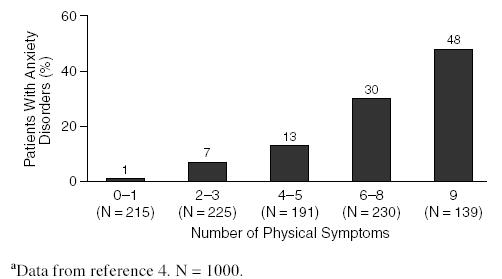

In 1989, Kroenke and Mangelsdorff2 looked at the percentage of their patients' physical complaints of an identified organic cause. Their findings are displayed in Figure 1. Kroenke and Mangelsdorff pointed out that patients frequently present with organ system symptoms, but that no organic cause can be found to explain the symptoms. In 1985, Bridges and Goldberg3 established that patients with known psychiatric disorders present more frequently with somatic symptoms than with psychological symptoms (Figure 2). In a later article by Kroenke et al.,4 the authors demonstrated that a relationship exists between the number of symptoms with which a patient presents and the increasing probability that such a patient has an anxiety disorder (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Percentage of Physical Complaints With Identified Versus Unidentified Organic Causesa

Figure 2.

Somatic Versus Psychological Complaintsa

Figure 3.

Number of Physical Symptoms and Prevalence of Anxiety Disordersa

All of these studies would support the contention that the patient in the above scenario most likely has some significant psychosocial issues underlying her reason for visiting the clinic. However, our biomedically oriented physician is struggling with how to come to grips with these issues. Just as the hospital has had to reinvent itself in order to adjust to the changing realities of the health care system, so too must physicians acquire new skills and capabilities if they expect to endure in the new climate. Fortunately, there is hope, and help is on the way. By the time you, the health care provider, finish this article, you should have a firm grasp of one method for dealing with this vexing issue. In the process, you will improve your own, as well as your patient's, quality of life while both of you adapt to this ever-changing environment.

ENHANCING THE DOCTOR/PATIENT RELATIONSHIP

If we are going to keep people well, help them to manage their chronic problems, and encourage them to adhere to medication regimens, a positive doctor/patient relationship is vital. Given the realities of the managed care environment, continuity of care is not always a viable option. It is crucial to establish good rapport and rapidly obtain the patient's trust. Key to this process is the ability to listen to the patient, provide support, legitimize concerns, elicit and reflect feelings, show respect, and establish a healing partnership.

Regardless of the thickness of the chart, it is a good idea to allow patients to “tell their story” without being interrupted for the first minute or two of the interview. Our tendency is to request details immediately, but if we temper this impulse, patients will usually provide pertinent information with very little prompting. Questions about particular aspects of the problem can then be posed. Adequate treatment of medical problems also includes confronting the psychological aspects. Whether or not the physician desires it, patients often expect help with emotional problems along with physical problems. It is important to find out what about the problem concerns the patient, what the patient was hoping you would do, and why the patient is coming for help at this time.

ASCERTAINING THE CONTEXT OF THE PATIENT'S VISIT

After eliciting the chief complaint and determining the patient's main concern, the physician can probe for the psychosocial context by BATHEing the patient.1

As a charting convention, the problem-oriented medical record classifies progress notes into subjective, objective, assessment, and plan elements (SOAP). Problems are listed and notes are arranged in SOAP fashion. In the larger context, BATHEing your patients as you SOAP them will give the physician useful information, take only about a minute, screen for emotional problems, and be therapeutic for the patient.

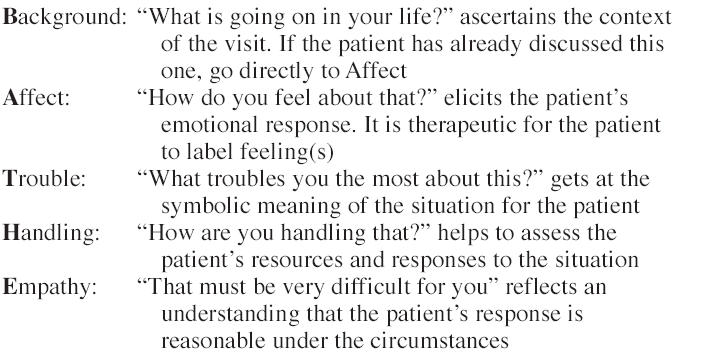

The BATHE technique is a simple patient-centered procedure that consists of a series of 4 specific questions about the patient's background, affect, troubles, and handling of the current situation, followed by an empathic response (Table 1).

Table 1.

The BATHE Procedure

When you BATHE a patient, you are performing a psychotherapeutic procedure. Psychotherapy means using your words and relationship with patients as procedures to affect patients' views of their reality. This therapy seeks to empower patients to trust themselves and others, confirm their positive feelings about themselves, and enhance their ability to control the circumstances of their lives.

The BATHE technique will also serve as a rough screening test for anxiety, depression, or situational stress disorders and should be routinely employed. It is an important technique to remember, because 25% to 75% of outpatient visits are triggered by these disorders.5 As a screening tool, the test is acceptable to patients, it catches these conditions early, and time costs are minimal.

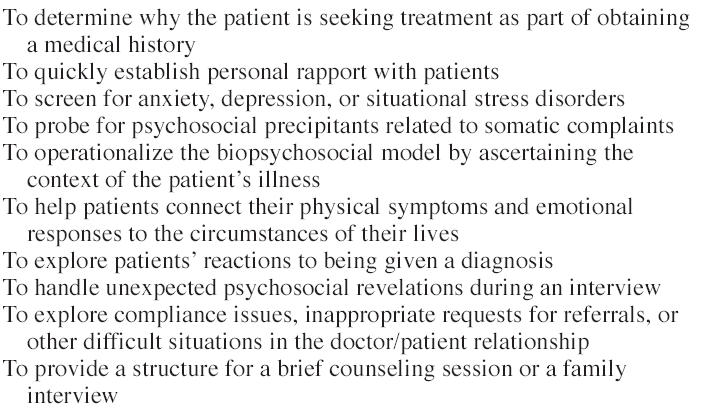

The BATHE technique is a specific verbal procedure. To be used effectively, it must be practiced. As with any procedure, some health care providers may feel awkward at first, but will develop confidence and a comfort level after doing a number of them correctly. The technique can be used for a variety of purposes, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Reasons to Use the BATHE Technique

SPECIFIC INSTRUCTIONS

When using the BATHE technique, try to say nothing except for the specific BATHE questions. Discourage patients from elaborating at length about the circumstances or details of their situations. Instead, summarize briefly and ask the next question.

Do not interpret or analyze the patients' responses. Resist giving advice. When patients answer the affect question by giving more background information, intervene quickly by repeating, “yes, but how do you feel about that?” until you get a response. When patients express positive feelings, do not presume that there is nothing troubling them. Instead, modify the T (trouble) question appropriately. Remember that it is not the health care worker's job to fix the patients' problems, only to provide support and clarification.

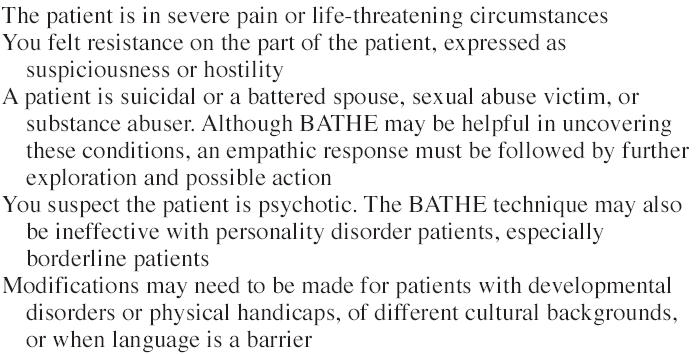

There are very few contraindications for using BATHE except for the ones shown in Table 3.6

Table 3.

Reasons Not to Use the BATHE Technique

FOLLOW-UP

When a psychosocial problem is uncovered, the health care provider can proceed with the physical examination to rule out organic problems and then ask the patient to return to discuss the situation further. When serious problems emerge, referral to a mental health specialist should be discussed. It is important, however, that both patient and physician are in accord that a problem exists and a follow-up visit to the physician is beneficial. When the patient returns, the opening BATHE question becomes “Tell me what's been happening since I saw you.” For further information and additional techniques, see The Fifteen Minute Hour.1

SUMMARY

Recognition that psychosocial aspects of patients' situations have a significant impact on the state of patients' health requires the physician to shift from a purely biomedical view to one that considers the whole patient and the context of the visit. Given a positive relationship with the patient, physicians can employ the BATHE technique to connect meaningfully with patients, screen for mental health problems, and empower patients to handle many aspects of their life in a more constructive way. When this is done in accordance with the protocol described, the whole procedure can be accomplished in about 1 minute.

REFERENCES

- Stuart MR, Lieberman JA. The Fifteen Minute Hour: Applied Psychotherapy for the Primary Care Physician. 2nd ed. Westport, Conn: Praeger. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Mangelsdorff D. Common symptoms in ambulatory care: incidence, evaluation, therapy and outcome. Am J Med. 1989;86:262–266. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(89)90293-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges KW, Goldberg DP. Somatic presentation of DSM-III psychiatric disorders in primary care. J Psychosom Res. 1985;29:563–569. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke J, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, et al. Physical symptoms in primary care: predictors of psychiatric disorders and functional impairment. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3:774–779. doi: 10.1001/archfami.3.9.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Arrington ME, Mangelsdorff AD. The prevalence of symptoms in medical outpatients and the adequacy of therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:1685–1689. doi: 10.1001/archinte.150.8.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart MR. The BATHE Technique. In: Rakel RE, ed. Saunders Manual of Medical Practice. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co. 1996 1108–1109. [Google Scholar]