Abstract

Background: Asthma and depression are both common illnesses. Data suggest that the prevalence of asthma and asthma-related morbidity and mortality has increased in the past 2 decades. Asthma has long been considered an illness in which mood and emotions contribute to symptom exacerbation. Therefore, we reviewed the recent literature on depression in persons with asthma.

Data Sources: The MEDLINE (1966–1999) and PSYCHINFO (1967–1999) databases were used to find English-language articles on asthma and depression. Search terms included asthma, depression, dysthymia, and mood.

Data Synthesis: This literature suggests depressive symptoms are more common in asthma patients than in the general population and perhaps even more common than in some other general medical conditions. Depression may be associated with asthma morbidity and mortality. Limited data suggest the older tricyclic antidepressants may improve both depression and asthma symptoms. However, no studies have examined the use of second-generation antidepressants in asthma patients.

Conclusion: Depressive symptoms are common in asthma patients. However, the prevalence of depressive disorders in this population is not well determined. Future studies should focus on determining the prevalence of major depressive disorder in this population and the effect of antidepressants on mood and asthma symptoms.

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is the most common mood disorder, with a lifetime prevalence in the general population of almost 20%.1,2 Depression is a debilitating illness that can cause severe functional impairment and emotional anguish. It is associated with significant income loss, absenteeism from work, and increased health care system costs.3–5 Depression appears to be particularly common in general medical settings. Current rates of depressive conditions ranging from 15% to 21% are reported in primary care populations.6–8 However, depression in primary care settings is often unrecognized and untreated.9–12

Depression may exacerbate symptoms of chronic general medical conditions13 and is associated with poor outcome in patients with diabetes, hypertension, and coronary artery disease.14,15 Frasure-Smith et al.15 reported that depression was a significant predictor of post–myocardial infarction mortality. Several studies of diabetic patients have linked depression to poor glucose control, higher glycosylated hemoglobin values, increased reporting of both hyperglycemic and hypoglycemic symptoms, and increased rates of complications.16–20

The presence of a general medical illness may also adversely affect the course of depressive disorders. Depressed diabetic patients were found to have 8 times the rate of depression relapse of depressed persons who were physically healthy.21 Numerous studies have shown that psychiatric symptoms in depressed patients with general medical illnesses appear to improve in response to antidepressant therapy.22 Imipramine improved mood in depressed patients with the human immunodeficiency virus.23 Nortriptyline therapy was associated with improvement in depressive symptoms compared with placebo in diabetic patients.24

As are diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease, asthma is a common, chronic, and debilitating general medical condition. Data suggest that the prevalence of asthma25,26 and asthma-related hospitalizations and deaths27–29 have increased in recent years. Historically, asthma has been considered a psychosomatic disease in which emotional stress plays a role in exacerbation of symptoms.30,31 Thus, we were interested in examining (1) the prevalence of depression in asthma patients, (2) the effect of depression on the course of illness, and (3) the effect of treatment for depression in asthma patients.

DATA SOURCES

A search of the MEDLINE (1966–1999) and PSYCHINFO (1967–1999) databases was conducted to find English-language studies and reviews investigating depression in asthma patients. Search terms included asthma, depression, dysthymia, and mood. We searched the bibliographies of these references to find additional research examining depression in asthma patients. Pertinent studies were divided into 3 categories: studies examining the prevalence of depressive symptoms in asthma patients, research assessing the effects of depression on the course of asthma, and research investigating the treatment of depression in asthma patients. In Table 1 (prevalence studies), we excluded studies with fewer than 50 subjects, since we felt inclusion of smaller studies would provide no useful data regarding depression prevalence. We also excluded studies published prior to 1975, since (1) their assessment techniques for depression were substantially different from those found in more recent studies and (2) diagnostic criteria for asthma have changed. Given the very small number of studies examining the use of antidepressants in asthma patients, we used less stringent inclusion criteria and discuss studies published prior to 1975.

Table 1.

Prevalence of Depression in Asthma Patientsa

RESULTS

Eight studies32–39 examining the prevalence of depressive symptoms in asthma patients met our inclusion criteria (see Table 1). Six of these were controlled studies,32–36,38 and all but 1 of these32 presented data consistent with a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms in asthma patients than in control groups. In the largest of the controlled studies, Badoux and Levy34 administered the Brief Symptom Inventory, a self-report questionnaire, to asthma patients (N = 102), normal controls (N = 252), and socially isolated individuals (N = 383) and found that asthma patients had significantly higher scores (p < .005) than normal controls, but lower scores than socially isolated individuals (p < .001). Lyketsos et al.36 found higher scores on the depression subscale of the Scale of Anxiety and Depression in asthma patients (N = 35) than in a group of controls with a variety of illnesses (N = 165), including alopecia, psoriasis, urticaria, irritable bowel syndrome, ulcers, ulcerative colitis, and hypertension. Only patients with rheumatoid arthritis (N = 37) had higher depression scores than the asthma patients. Dyer and Sinclair32 found no significant difference in prevalence of depressive symptoms (p = .32) in elderly asthma patients (N = 40) than in normal controls (N = 40). However, a much higher percentage of asthma patients than controls had elevated depression scores. Thus, the small sample size and resulting low statistical power may limit the certainty of these negative findings.

Three of the studies33,35,38 examined depressive symptoms in children and adolescents with asthma. Seigel and Golden35 found that adolescents with asthma (N = 40) had significantly higher Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) scores than did normal controls (p < .001) and scores similar to patients with sickle cell disease and diabetes. Since the subjects were relatively asymptomatic outpatients, the investigators suggested that the increase in depressive symptoms was not related to asthma symptoms. Padur et al.33 found significantly higher scores on the Child Depression Inventory in children with asthma (N = 25) than in children with diabetes (N = 25) or cancer (N = 25) or in healthy controls (N = 25). Meijer38 examined dependency and emotional disturbance in children with asthma (N = 31) and found that low-dependency boys with asthma had significantly more depressive symptoms (p = .05), as determined by the Mother-Child Questionnaire, than nonasthmatic low-dependency boys. Low-dependency girls with asthma also showed more depression than their high-dependency counterparts, but the difference was not significant.

Two uncontrolled studies37,39 meeting the inclusion criteria and examining the prevalence of depression or depressive symptoms in asthma patients were also found. As with the controlled studies, both identified depressive traits or symptoms and did not diagnose depressive disorders. Jones et al.39 administered the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) to hospitalized adult asthma patients and found that 72/147 (49%) had elevated scores on the “neurotic triad” (scales of hypochondriasis, depression, and hysteria). Teiramaa,37 using the semistructured psychiatric interview along with the BDI and MMPI, identified depressive symptoms or a diagnosis of depressive neurosis in over half (53%) of the asthma subjects (N = 100).

Relationship of Depression to Asthma Symptoms

Nine studies meeting our criteria assessed the relationship between depression and the course of asthma and are given in Tables 2 and 3.40–48 Three studies40–42 suggested that depression may increase risk of death from asthma (see Table 2). Strunk et al.42 examined 21 children who later died of asthma and a monitored control group. The group with fatal asthma showed evidence of greater “behavioral disturbance” (18/21 vs. 9/21; p > .01) and exhibited more depressive symptoms (16/21 vs. 9/21; p < .05). Picado et al.41 reported that 4/6 (66%) patients who died from asthma exacerbations required treatment for a “syndrome of anxiety-depression.” Interestingly, all 4 of the patients with depression who died had recently stopped taking prescribed psychotropic medication before the fatal attack. Mascia et al.40 retrospectively reviewed the psychological characteristics of severely asthmatic children admitted to the hospital over a 10-year period. Although not statistically significant, depressive symptoms were found in 77% (N = 9) of fatalities in this population while only 53% (N = 72) of survivors had depressive symptoms.

Table 2.

Depression and Asthma–Related Death

Table 3.

Depression and Asthma Severitya

However, not all studies have found a consistent association between severity of asthma and depression (see Table 3). Yellowlees et al.48 examined patients with near-fatal asthma attacks (N = 13) and a control group with less severe illness (N = 36) and found a 33% overall prevalence rate of psychopathology in both groups. One subject in the study group (1/13, 8%) and one in the control group (1/36, 3%) were diagnosed with “depressive illness” according to DSM-III criteria, suggesting low rates of mood disorders in both groups.

Allen et al.46 suggested a possible etiologic link between depression and death from asthma. These investigators found that asthma patients with depression as indicated by scores derived from the Profile of Mood States questionnaire showed a 3-fold increased risk for an impaired voluntary drive to breathe when compared to euthymic asthma patients. Poor compliance with asthma treatment may also contribute to risk of a fatal attack. Bosley et al.44 found significantly higher scores (p < .05) on the depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in patients who were noncompliant (N = 37) with their inhaled β-agonists and steroids than in those patients who were compliant with medication (N = 35).

Three studies43,45,47 suggested that depression might be related to increased asthma symptom reporting. In a population-based study (N = 715), Janson et al.45 found a correlation between depression and self-reported asthma-related symptoms, but no correlation between a diagnosis of asthma and depression or objective asthma-related measurements (e.g., spirometry) and depression. Janson-Bjerklie et al.47 found that elevated scores on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale were related to subjectively perceived asthma severity and danger, but not to objective asthma severity as indicated by medication, intubation history, and hospitalization frequency. Similarly, Rushford et al.43 found that “exaggerated perceivers” of asthma-related airflow obstruction had higher scores (p = .026) on the Self-Rated Depression Scale than “normal perceivers.”

Antidepressant Therapy in Asthma Patients

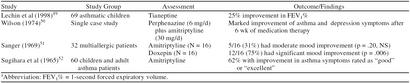

Four reports49–52 were found examining the use of antidepressants in asthma patients (Table 4). Two of these studies49,52 examined the efficacy of antidepressants in treating asthma-related symptoms in nondepressed patients. Sugihara et al.52 administered amitriptyline to 60 asthma patients, finding a “good” to “excellent” response in asthma symptoms in 62% of the subjects. The best response (79%) was observed in children under 15 years of age (N = 14). In a double-blind crossover design, Lechin et al.49 also observed a mean improvement of 25% in 1-second forced expiratory volume (FEV1% rates) in children with asthma (N = 69) treated with the selective serotonin reuptake enhancer tianeptine.

Table 4.

Antidepressant Therapy in Asthmaticsa

Two reports50,51 of improvement in mood in depressed asthma patients given antidepressants were found. Sanger51 compared amitriptyline and doxepin in a randomized double-blind study investigating the treatment of anxiety and depression in patients with multiple allergies, including dermatologic conditions, hay fever, and bronchial asthma. Doxepin was significantly more effective than amitriptyline at reducing Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression scores in this population. Overall, 12 of 16 doxepin-treated patients reportedly showed moderate-to-marked improvement in their overall scores, whereas 5 of 16 amitriptyline-treated patients showed moderate improvement at best. The potent antihistamine effects of doxepin, which ameliorate allergic reactions and promote bronchodilation, may in part explain the greater improvement in emotional symptoms with doxepin.

Wilson50 reported the case of a 48-year-old female patient who suffered from asthma symptoms until she was given a combination of perphenazine (6 mg/day) and amitriptyline (30 mg/day) for anxiety and depression. After taking this regimen for 6 weeks, the patient reported that her asthma medications were discontinued and that her asthma remained in remission during the 3-month assessment period.

DISCUSSION

Virtually all studies suggest that depressive symptoms are more common in asthma patients than in the general population. Since only one study40 examined the prevalence of MDD rather than depressive symptoms, the rates of formal mood disorders in asthma patients cannot be assessed. Minimal data were found comparing the prevalence of depression in asthma with that in other chronic illnesses. The available studies34,36 suggest rates of depressive symptoms may be more common in asthma than in some other severe illnesses. However, the presence of depressive disorders, not symptoms, is the basis for psychiatric diagnosis and treatment. Thus, given the available data, the prevalence of clinically significant depression in asthma patients cannot be determined.

One limitation in studies examining depressive symptoms in medically ill populations is the possibility of increased scores on depression measures due to the physical symptoms of the illness. Asthma symptoms can cause insomnia and asthma medications (e.g., β-agonists) can cause anxiety; both of these symptoms elevate scores on some depression scales. However, the elevated scores on the BDI, which emphasizes psychological rather than neurovegetative symptoms of depression, reported by Seigel and Golden.35 and Teiramaa et al.37 suggest that asthma symptoms alone do not fully explain the elevated depression scores generally observed.

Data from external studies may provide evidence supporting a possible biological link between asthma and depression. Flinders line rats are very sensitive to the effects of cholinergic agents and exhibit depressive behavior in some animal models of depression.53 This breed of rat also exhibits airway hyper-responsiveness after exposure to allergens.54 In human studies, a subset of asthma patients55,56 as well as a subset of persons with depression exhibit evidence of glucocorticoid resistance.57,58 Additional controlled studies are needed, examining the prevalence of depression in asthma patients and persons with comparable disability from other general medical conditions, to determine if asthma patients are at increased risk of depression compared with other general medical conditions.

Data on the effect of depression on asthma are mixed, with some studies suggesting poor compliance with care, more severe airway obstruction, and even increased risk of asthma-related deaths in depressed asthma patients than nondepressed asthma patients. The association of depression with asthma-related mortality is of particular concern. However, these studies have methodological limitations, including retrospective designs and small sample sizes. If confirmed, the increased mortality risk may be consistent with data suggesting increases in cholinergically mediated airway constriction associated with stress or negative mood states.59–61 However, other data suggest that depressed patients subjectively perceive themselves as having more severe asthma symptoms than euthymic patents, but this perception is not supported by objective measures of disease severity.43,45,47 In addition, preliminary data from our group suggest less severe airway obstruction, as measured with spirometry, in asthma patients with a history of a mood disorder than in those without a mood disorder.62 Thus, asthma patients with depression may see themselves as having more severe asthma, which could lead these patients to seek further health care treatment. A greater number of emergency room visits, greater frequency of appointments, and more aggressive treatment in the depressed asthmatic potentially could lead to an improvement in symptoms, but also greater cost due to overutilization of medical services. One possible explanation for the seemingly dichotomous findings of increased risk of death and exaggerated perception of asthma symptoms is that there may be 2 subsets of depressed asthma patients: a group with severe asthma in which depression may lead to poor medication compliance and an increased risk of mortality, and a second group with mild asthma and symptoms of anxiety, depression, and somatic complaints who may tend to utilize medical services more often (e.g., emergency rooms).

In contrast to data in other chronic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, few studies in the current medical literature report the effects of treatment of depression in asthma patients. These include a single case report50 and one small uncontrolled study51 that used antidepressants infrequently prescribed in current practice. Even though several clinical trials suggest that antidepressants may improve both physical and psychological symptoms in other general medical conditions, there has been no clinical trial using second-generation antidepressants (e.g., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) to treat depression in asthma patients. Clearly, clinical trials of antidepressant agents are needed in asthma patients and will allow comparisons to be made among depressive symptoms, medication compliance, and both objective and subjective measures of disease severity.

CONCLUSION

In summary, the relationship of depression to asthma symptoms has been the topic of surprisingly little investigation. Given data which suggest that asthma prevalence, morbidity, and mortality are increasing and evidence that suggests an association between depression and asthma–related deaths, further research in the area is needed. Since antidepressant therapy is associated with both improvement in mood and physical symptoms in other general medical conditions, clinical trials are needed in asthma patients using both depressive symptoms and asthma symptoms as outcome measures.

Drug names: amitriptyline (Elavil and others), doxepin (Sinequan and others), nortriptyline (Pamelor and others), perphenazine (Trilafon and others).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Leonardo Bobadilla, B.A., for proofreading the article.

Footnotes

Supported in part by the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD), the Sarah M. and Charles E. Seay Center for Basic and Applied Research in Psychiatric Illness, the John Schemerhorn Psychiatric Fund, and the Theodore and Vada Stanley Foundation.

REFERENCES

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, et al. Comorbidity of DSM-III-R major depressive disorder in the general population: results from the National Comorbidity Study. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;168(suppl 30):17–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg PE, Stiglin LE, Finkelstein SN. The economic burden of depression in 1990. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54:405–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Barber C, Birnbaum HG, et al. Depression in the workplace: effects on short-term disability. Health Aff (Millwood) 1999;18:163–171. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.5.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice DP, Miller LS. The economic burden of affective disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;166(suppl 27):34–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielson AC, Williams TA. Depression in ambulatory medical patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980;37:999–1004. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780220037003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical Practice Guideline Number 5: Depression in Primary Care, vol 1. Detection and Diagnosis. Rockville, Md: US Dept Health Human Services, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1993. AHCPR publication 93-0550. [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, VonKorff M, Barlow W. Health care costs of primary care patients with recognized depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:850–856. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950220060012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulberg HC, Saul M, McClelland M. Assessing depression in primary medical and psychiatric practices. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;12:1164–1170. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790350038008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Berg AO, Robins AJ, et al. Depression: medical utilization and somatization. West J Med. 1986;144:564–568. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Stable EJ, Miranda J, Munoz RF, et al. Depression in medical outpatients: underrecognition and misdiagnosis. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:1083–1088. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1990.00390170113024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuaid JR, Stein MB, Laffaye C, et al. Depression in a primary care clinic: the prevalence and impact of an unrecognized disorder. J Affect Disord. 1999;55:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Sullivan MD. Depression and chronic medical illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51(6, suppl):3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells KB, Rogers W, Burman MA, et al. Course of depression in patients with hypertension, myocardial infarction, or insulin-dependent diabetes. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:632–638. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.4.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F, Talajic M. Depression and 18-month prognosis after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1995;91:999–1005. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.4.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkington RW. Depression masquerading as diabetic neuropathy. JAMA. 1980;243:1147–1150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustman PJ, Clouse RE, Carney RM. Depression and the reporting of diabetes symptoms. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1988;18:295–303. doi: 10.2190/lw52-jfkm-jchv-j67x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuttner MJ, Delamater AM, Santiago JV. Learned helplessness in diabetic youths. J Pediatr Psychol. 1990;15:581–594. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/15.5.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tun PA, Nathan DM, Perlmuter LC. Cognitive and affective disorders in elderly diabetics. Clin Geriatr Med. 1990;6:731–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leedom L, Meehan WP, Procci W, et al. Symptoms of depression in patients with type II diabetes mellitus. Psychosomatics. 1991;32:280–286. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(91)72066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustman PJ, Griffith LS, Clouse RE. Depression in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1988;11:605–612. doi: 10.2337/diacare.11.8.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill D, Hatcher S. A systematic review of the treatment of depression with antidepressant drugs in patients who also have a physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:131–143. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabkin JG, Rabkin R, Harrison W, et al. Effect of imipramine on mood and enumerative measures of immune status in depressed patients with HIV illness. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:516–523. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.4.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustman PJ, Griffith LS, Clouse RE, et al. Effects of nortriptyline on depression and glycemic control in diabetes: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Psychosom Med. 1997;59:241–250. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199705000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- From the Centers for Disease Control. Asthma: United States, 1980–1990. JAMA. 1992;268:1995–1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman M, Gortmaker SL, Sobol AM, et al. Recent trends in the prevalence and severity of childhood asthma. JAMA. 1992;268:2673–2677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannino DM, Homa DM, Pertowski CA, et al. Surveillance for asthma: United States, 1960–1995. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep CDC Surveill Summ. 1998;47:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans R III, Mullally DI, Wilson RW, et al. Prevalence, hospitalization and death from asthma over two decades: 1965–1984. Chest. 1987;91:65S–74S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss KB, Wagener DK. Changing patterns of asthma mortality identifying target populations at high risk. JAMA. 1990;264:1683–1687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vachon L. Respiratory disorders. In: Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ, eds. Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, VI. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins. 1995 1501–1514. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin NJ. Severe asthma and depression. Arch Fam Med. 1993;2:433–440. doi: 10.1001/archfami.2.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer CAE, Sinclair AJ. A hospital-based case-control study of quality of life in older asthmatics. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:337–341. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10020337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padur JS, Rapoff MA, Houston BK, et al. Psychosocial adjustment and the role of functional status for children with asthma. J Asthma. 1995;32:345–353. doi: 10.3109/02770909509082759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badoux A, Levy DA. Psychologic symptoms in asthma and chronic urticaria. Ann Allergy. 1994;72:229–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seigel WM, Golden NH. Depression, self-esteem, and life events in adolescents with chronic diseases. J Adolesc Health. 1990;11:501–504. doi: 10.1016/0197-0070(90)90110-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyketsos CG, Lyketsos GC, Richardson SC, et al. Dysthymic states and depressive syndromes in physical conditions of presumably psychogenic origin. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1987;76:529–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1987.tb02914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teiramaa E. Psychosocial and psychic factors and age at onset of asthma. J Psychosom Res. 1979;23:27–37. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(79)90068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer A. Emotional disorders of asthmatic children. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 1979;9:161–169. doi: 10.1007/BF01433479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones NF, Kinsman RA, Schum R, et al. Personality profiles in asthma. J Clin Psychol. 1976;32:285–291. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(197604)32:2<285::aid-jclp2270320218>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascia A, Frank S, Berkman A, et al. Mortality versus improvement in severe chronic asthma: physiologic and psychologic factors. Ann Allergy. 1989;62:311–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picado C, Montserrat JN, de Pablo J, et al. Predisposing factors to death after recovery from a life-threatening asthmatic attack. J Asthma. 1989;26:231–236. doi: 10.3109/02770908909073254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strunk RC, Mrazek DA, Fuhrmann GS, et al. Physiologic and psychological characteristics associated with deaths due to asthma in childhood. JAMA. 1985;254:1193–1198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushford N, Tiller JWG, Pain MCF. Perception of natural fluctuations in peak flow in asthma: clinical severity and psychological correlates. J Asthma. 1998;35:251–259. doi: 10.3109/02770909809068215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosley CM, Fosbury JA, Cochrane GM. The psychological factors associated with poor compliance with treatment in asthma. Eur Respir J. 1995;8:899–904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janson C, Bjornsson E, Hetta J, et al. Anxiety and depression in relation to respiratory symptoms and asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:930–934. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.4.8143058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen GM, Hickie I, Gandevia SC, et al. Impaired voluntary drive to breathe: a possible link between depression and unexplained ventilatory failure in asthmatic patients. Thorax. 1994;49:881–884. doi: 10.1136/thx.49.9.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janson-Bjerklie S, Ferketich S, Benner P, et al. Clinical markers of asthma severity and risk: importance of subjective as well as objective factors. Heart Lung. 1992;21:265–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yellowlees PM, Haynes S, Potts N, et al. Psychiatric morbidity in patients with life-threatening asthma: initial report of a controlled study. Med J Aust. 1988;149:246–249. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1988.tb120596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechin F, van der Dijs B, Orozco B, et al. The serotonin uptake-enhancing drug tianeptine suppresses asthmatic symptoms in children: a double-blind, crossover, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;38:918–925. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1998.tb04387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RCD. Antiasthmatic effect of amitriptyline [letter] Can Med Assoc J. 1974;111:212. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger MD. The treatment of anxiety and depression in the allergic patient: case report. Ann Allergy. 1969;27:506–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugihara H, Ishihara K, Noguchi H. Clinical experience with amitriptyline (tryptanol) in the treatment of bronchial asthma. Ann Allergy. 1965;23:422–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet DH, Steiner M. Genetic and environmental models of stress-induced depression in rats. Stress Med. 1998;14:261–268. [Google Scholar]

- Djurie VJ, Cox G, Overstreet DH, et al. Genetically transmitted cholinergic hyperresponsiveness predisposes to experimental asthma. Brain Behav Immun. 1998;13:272–284. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1998.0538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane SJ, Lee TH. Mechanisms of corticosteroid resistance in asthmatic patients. Int Arch Allergy Immun. 1997;113:193–195. doi: 10.1159/000237544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung DY, Spahn JD, Szefler SJ. Immunologic basis and management of steroid-resistant asthma. Allergy Asthma Proc. 1999;20:9–14. doi: 10.2500/108854199778681512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowy MT, Reder AT, Antel JP, et al. Glucocorticoid resistance in depression: the dexamethasone suppression test and lymphocyte sensitivity to dexamethasone. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141:1365–1370. doi: 10.1176/ajp.141.11.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arana GW, Baldessarini JR, Ornsteen M. The dexamethasone suppression test for diagnosis and prognosis in psychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;42:1193–1204. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790350067012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr RE, Lehrer PM, Hochron SM, et al. Effect of psychological stress on airway impedance in individuals with asthma and panic disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 1996;105:137–141. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer PM, Hochron S, Carr R, et al. Behavioral task-induced bronchodilation in asthma during active and passive tasks: a possible cholinergic link to psychologically induced airway changes. Psychosom Med. 1996;58:413–422. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199609000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BD, Wood BL. Influence of specific emotional states on autonomic reactivity and pulmonary function in asthmatic children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:669–677. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199705000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown ES, Nejtek V, Khan DA, and et al. Depression in asthma patients: preliminary findings. In: Society of Biological Psychiatry 55th Annual Scientific Convention and Program; May 11–13, 2000; Chicago, Ill. No. 47. 8S. [Google Scholar]