Abstract

The International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety has held 7 meetings over the last 3 years that focused on depression and specific anxiety disorders. During the course of the meeting series, a number of common themes have developed. At the last meeting of the Consensus Group, we reviewed these areas of commonality across the spectrum of depression and anxiety disorders. With the aim of improving the recognition and management of depression and anxiety in the primary care setting, we developed an algorithm that is presented in this article. We attempted to balance currently available scientific knowledge about the treatment of these disorders and to reformat it to provide an acceptable algorithm that meets the practical aspects of recognizing and treating these disorders in primary care.

Since its inception in 1997, the International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety has hosted 7 meetings, where experts in the field have met with us to develop consensus views on the recognition and management of specific anxiety disorders (panic disorder,1 social anxiety disorder,2 generalized anxiety disorder,3 and posttraumatic stress disorder4); depression in primary care5; depression and anxiety in gastroenterology,6 cardiology,7 and oncology8; and on transcultural issues in depression and anxiety.9

In January 2001, we met as a group to reflect on advances in the field and formulate our views on how to improve the recognition, diagnosis, and management of what is called the spectrum of depressive and anxiety disorders. We began by reviewing the evidence to support serotonergic involvement in these disorders across the spectrum. We went on to discuss diagnostic scales and consider the most appropriate approach for the recognition and diagnosis of spectrum disorders in primary care, and we ended by developing management guidelines that can be applied across the spectrum of depressive and anxiety disorders. This article covers these aspects of the meeting and, in addition, proposes a simple diagnostic screening questionnaire and treatment algorithm suitable for use by primary care physicians.

EVIDENCE FOR A COMMON NEUROBIOLOGY ACROSS THE SPECTRUM OF DEPRESSION AND ANXIETY DISORDERS

The clinical use of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) has expanded over the past decade to include the treatment of not only depression but also all of the anxiety disorders.10,11 Clinical efficacy in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD),12–14 panic disorder,15–20 social anxiety disorder,21–24 and most recently generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)25,26 and posttraumatic stress disorder27–32 has been demonstrated for members of this drug class, most notably paroxetine, which is licensed for all these disorders. Given the wide spectrum of disorders that are effectively treated with SSRIs, considerable interest has centered on understanding how the single action of inhibiting serotonin reuptake can improve such diverse psychiatric conditions. Furthermore, it has led some clinicians to question whether anxiety disorders are indeed distinct from depression or simply different expressions of major depressive disorder.

We recognize that significant overlap in the symptomatology of the anxiety disorders and depression is evident. For example, sleep disturbances such as insomnia and alterations in appetite and libido are common in both anxiety and depression. However, there are also symptoms specific to anxiety disorders (e.g., hypervigilance) and others particular to depression (e.g., anhedonia and low mood). This suggests that anxiety disorders and depression are distinct diagnostic entities.

Further support for the latter view is obtained by comparing differences in biological findings between the disorders (e.g., sleep patterns). Patients with depression or GAD have reductions in total sleep time,33–36 reduced sleep efficiency, and insomnia.33,34 However, while patients with depression have shortened REM latency and as a consequence a higher percentage of REM sleep time than normal,35,36 this is not the case in patients with GAD and other anxiety disorders.34,35

There are also important differences in the development of the therapeutic effect of SSRIs across the disorders. Firstly, the response to treatment is faster in depression (3–4 weeks) than in some of the anxiety disorders (up to 12 weeks in OCD). Secondly, the therapeutic dose requirements seem to vary between the disorders at least for some drugs. For instance, in the case of paroxetine, efficacy in both panic disorder17 and OCD37 was found at doses above that generally needed for depression; this finding may reflect differential sensitivity of the serotonin reuptake transporter in the different brain circuits. Finally, in the treatment of panic disorder, an initial worsening of symptoms during the first few weeks of treatment has been noted with all antidepressants. This “onset-worsening” is not seen in depression, OCD, or social anxiety disorder. These observations underscore the view that different pathways may be involved in mediating the therapeutic actions of antidepressants such as the SSRIs.

In order to explain how a single mode of action can lead to improvement across the spectrum of disorders, it is necessary to consider where serotonin acts in the pathogenic process underlying depression and the various anxiety disorders. Attention has focused on the 2 main serotonergic pathways in the brain: ascending projections from the medial and dorsal raphe and descending projections from the caudal raphe into the spinal cord. The ascending pathways are particularly diverse in nature, and projection areas include the frontal cortex, striatum, thalamus, amygdala, hypothalamus, and hippocampus. It would seem plausible that various central nervous system (CNS) disorders mediated at least in part by serotonin may involve various pathways as well as different serotonin receptor subtypes. Serotonergic neurons arising from the median raphe nucleus, which innervate the 5-HT1A receptors in the temporal lobe and hippocampus, are thought to be implicated in depression, whereas serotonergic connections between the dorsal raphe and amygdala that innervate 5-HT2 receptors may play an important role in regulating anxiety.

At the level of the serotonergic synapse, the SSRIs act by inhibiting the reuptake of serotonin into the presynaptic nerve terminal, thus increasing the level of serotonin available to interact with either postsynaptic or presynaptic autoreceptors. The role of 5-HT receptors and receptor desensitization in depression and anxiety disorders has been investigated in a number of studies. The receptors that are thought to be most involved in the efficacy of SSRIs in these disorders are the 5-HT1A receptors. Using a selective 5-HT1A receptor agonist ([11C]-WAY-100635), positron emission tomography (PET) has shown that in depression there is down-regulation of presynaptic and postsynaptic receptors. In major depressive disorder, PET has shown reduced 5-HT1A receptor binding across most cortical areas of the brain and the raphe nuclei.38 This reduction in 5-HT1A receptor binding was not changed following chronic SSRI treatment.38

Statistical Parametric Map (SPM) analysis of the binding potential in paroxetine-treated panic disorder patients compared with controls has shown that there is reduced 5-HT1A receptor binding in a number of brain regions.39 This reduction in binding potential in panic disorder occurs in areas of the brain similar to those seen in depression.38 While this observation could be considered evidence of a linked etiology between depression and panic disorder, until we can compare binding data in untreated panic disorder and depressed patients, we will not know whether this is related to drug treatment or an effect of the illness per se.

A further approach to the investigation of the SSRI mechanism of action has involved assessing whether increased synaptic levels of serotonin are required for the SSRIs to produce their therapeutic effects. The brain synthesizes serotonin from the precursor tryptophan, which comes mainly from the diet. If the dietary availability of tryptophan is reduced, a decrease in serotonin synthesis occurs and brain levels of serotonin are reduced. It has been shown that depletion of serotonin in the brain may cause a relapse in depressed patients receiving SSRIs.40,41 However, tryptophan depletion does not result in relapse in patients with OCD who have responded to SSRI treatment.42,43

More recently, patients with panic disorder, who had recovered following paroxetine treatment, participated in a tryptophan-depletion study. When plasma tryptophan was depleted, 3 of the 8 patients became depressed when given a flumazenil challenge and, more importantly, 5 of the 8 suffered anxiety and essentially relapsed.44 The relapse observed in previously recovered depression and panic disorder patients following tryptophan depletion suggests that increased levels of serotonin must be present in the synapse for SSRIs to be effective in these conditions. Since no change is seen in OCD symptoms following tryptophan depletion, receptor adaptation may be more important than serotonin levels in mediating the efficacy of SSRIs in this disorder, and this may also explain the delayed onset of therapeutic effect. Tryptophan depletion studies following SSRI treatment are ongoing for social anxiety disorder and GAD.

DIAGNOSTIC INSTRUMENTS FOR DEPRESSION AND ANXIETY

A number of diagnostic instruments have been proposed for use in primary care, including the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD),45 the Symptom-Driven Diagnostic System for Primary Care (SDDS-PC),46 the General Healthcare Questionnaire (GHQ),47 the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depressed Mood Scale (CES-D),48 and more recently the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI).49–51

The PRIME-MD questionnaire consists of 2 parts: a screening questionnaire that is completed by the patient and a categorical diagnostic checklist that is completed by the physician. Diagnostic categories are checked according to the orientation indicated by the patient's answers. PRIME-MD explores only a limited spectrum of disorders: major depression, anxiety, somatoform disorders, eating disorders, and alcohol abuse. It is a self-assessment form, and symptoms need to have been present for 1 month. A degree of validation of this questionnaire has taken place by both primary care physicians and health care professionals who have shown it to be an acceptable instrument for the diagnosis of mood disorders but unacceptable for the diagnosis of other psychological disorders by a primary care physician.45 The SDDS-PC is also a patient-administered questionnaire, which explores 16 symptoms covering 6 diagnostic areas; this instrument has been developed from a more extensive (62 symptom) version. If the patient has a positive response in 1 area, a specific physician-administered module is then used. The criteria in the SDDS-PC are more precise than those in the PRIME-MD and include symptom duration and impairments caused by the symptoms. The possible existence of physical illness must be ruled out. The SDDS-PC is a longitudinal tracking form that explores the diagnosis of a limited number of disorders—major depression, GAD, OCD, panic disorder, alcohol abuse, and suicidal behavior. Validation of this instrument has again raised questions regarding its suitability for use in primary care due to the difficulties in collecting the correct information.46

The General Healthcare Questionnaire (GHQ)47 assesses symptoms and the general distress caused by depression and/or anxiety disorders. It is not a diagnostic tool but a list of either 12 (GHQ-12) or 28 (GHQ-28) questions. As part of the World Health Organization (WHO) Collaborative Study on Psychological Problems in General Health Care (PPGHC), the GHQ was administered to 5269 consecutive primary care patients.52 The data showed a linear relationship between GHQ-12 score and percentage recognition by general practitioners; however, the GHQ appears to be most useful in identifying those patients most severely affected, and a disadvantage of the questionnaire is that it is not diagnosis-specific.

Many diagnostic instruments have limitations that make them unsuitable for use in primary care; for example, either they are time consuming to complete and to score, not all disorders are covered, sensitivity and validity have not been fully explored, or only limited language translations are available. This was the background to the development of the MINI, which was developed jointly by psychiatrists and clinicians in the United States and Europe, for DSM-IV and ICD-10 psychiatric disorders. In a validation study versus the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI),53 which was considered the gold standard, the MINI had high specificity, sensitivity, and positive predictive values for all the depressive and anxiety disorders tested with the exception of GAD. However, following amendments to the questions asked, results equivalent to those seen with the other disorders can now be achieved for GAD.54,55 Similar results were observed against the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R in the United States.49

The diagnoses made by primary care physicians using the MINI have been compared with the diagnoses made by a specialist. When the MINI was used, diagnostic concordance with the specialist was high for almost all disorders (positive predictive values of approximately 70%), a finding that was all the more notable given that in the absence of a structured interview an accurate diagnosis is achieved in only 15% of cases.52 The results of this study suggest that with the use of this short structured diagnostic interview there is an increased rate of recognition of depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care.55

A further investigation in primary care patients in France has examined the positive predictive value of using only the screening questions that are contained at the beginning of each diagnostic module in the MINI. Consecutive primary care patients completed a questionnaire containing the 17 screening questions, and the “self-report” diagnosis was compared with that reached by a specialist following a telephone interview; the positive predictive value of the screening questions was found to be 68.5%. This shortened screening form of the MINI takes only 5 to 10 minutes to complete; nevertheless, in two thirds of cases where the presence of a psychiatric disorder was identified, this would be confirmed by further investigation.

CONSENSUS VIEWS ON RECOGNITION AND DIAGNOSIS

Our objective was to define ways of recognizing and diagnosing depression and anxiety disorders more effectively and accurately, leading to improvements in the management of these prevalent conditions. We support a 2-stage approach to recognition and diagnosis. Stage 1 is the alerting process with the application of a screening questionnaire to assess the need for further psychological testing. Stage 2 is the diagnostic process to confirm the physician's increased suspicion about the presence of a psychiatric condition from the answers to the questionnaire.

Stage 1: Screening

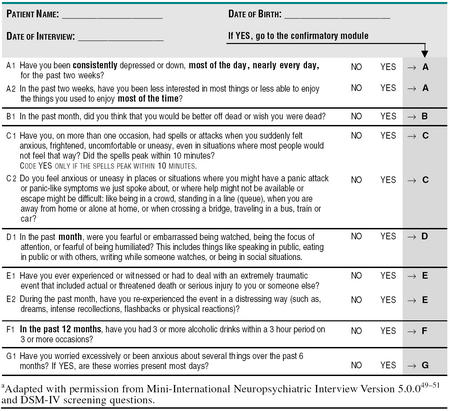

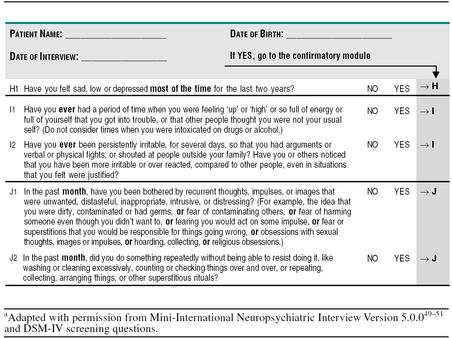

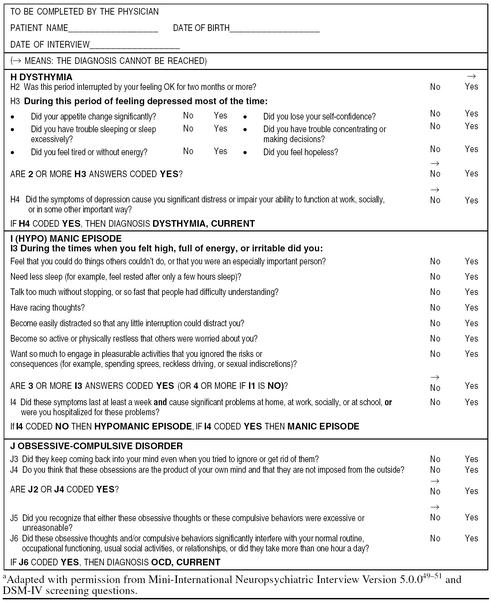

The issue is what screening questions to ask and when to ask them. As we are working in an international context, we need to recommend questions that have been validated in multiple languages, and so we turned to the MINI, which is the only diagnostic tool with multiple language validation. Our consensus recommendation is to use 10 of the 17 screening questions contained in the diagnostic modules of the MINI (Table 1A) as a core questionnaire. These would effectively screen for the most prevalent conditions: depression, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, GAD, and posttraumatic stress disorder. These short, high-yield questions would be presented to the patient on a single sheet, with the instruction to circle the ones that affect them. The patient would present the form to the physician, who will ask confirmatory questions (see Stage 2: Diagnosis [Table 1B]) if the answers prompt an index of suspicion for depression or an anxiety or substance abuse disorder. A second sheet containing additional questions that would document more rare diagnoses, e.g., OCD and includes screening questions for dysthymia and bipolar disorder, is also provided (Table 2A). These “optional” questions would allow the primary care physician to explore further diagnoses, e.g., dysthymia in situations where the patient has symptoms of depression but does not meet diagnostic criteria for major depression, or where all the other diagnoses are negative.

Table 1A.

Core Screening Questions to Identify Patients With Possible Psychiatric Diagnosis in the Primary Care Settinga

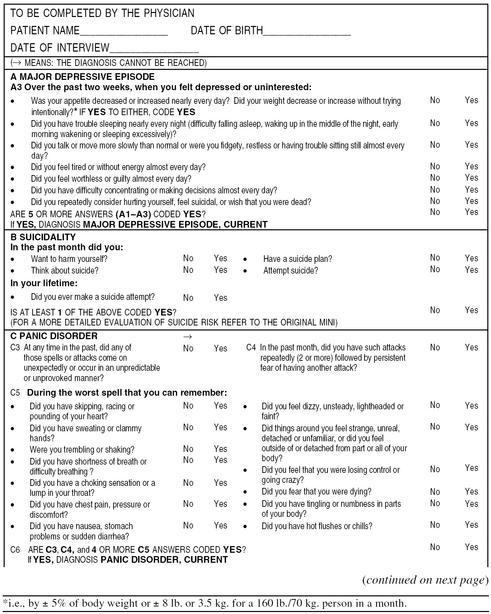

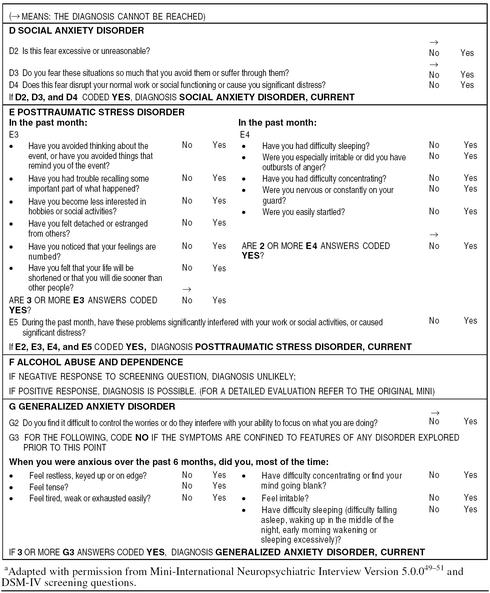

Table 1B.

Diagnostic Confirmatory Questions for Use by the Physician in Conjunction With the Core Screening Questionnairea

Table 1B.

Continued

Table 2A.

Additional “Optional” Screening Questions to Identify Patients With Further Psychiatric Diagnosis in the Primary Care Settinga

The most difficult problem for the physician would be when to apply the screening questionnaire. One option would be to ask every patient entering primary care to complete a form at their first visit and then once a year. Screening for psychiatric disorders could then become as routine as blood pressure monitoring. We would argue that this would be appropriate since the disorders are even more prevalent, yet are not diagnosed in the majority of patients. Nonetheless, we must recognize that this is a multinational and multilanguage issue, and it will be difficult to get a single paradigm with regard to when to apply the screening questionnaire. Some physicians may be comfortable with screening all elderly patients coming into the surgery. Others may want a patient to fill out a questionnaire when they suspect the presence of any psychiatric problem.

The most common symptoms of depression or anxiety, the most commonly associated physical illnesses, and functional impairment could act as guides to the patient groups to target for screening. The screening questionnaire should be completed when the physician suspects that the patient has a psychological illness such as depression or anxiety (for example, the patient has had a panic attack); when the patient has symptoms indicative of anxiety and depression, such as insomnia or pain; when there is psychological distress (for example, loss of interest or pleasure, distress, or tearfulness), persistent unexplained physical symptoms, or a recent decrease in functional ability. The ability to function normally at work or socially is compromised by psychiatric problems, which is why the physician should question whether patients have experienced a recent problem with work performance or significant change in their ability to manage their responsibilities in their personal, social, or family lives. The aim is not to discover whether there is a reason for a psychiatric problem, but rather to use decreased functionality as an indicator of psychiatric illness.

Stage 2: Diagnosis

After the initial screening, the physician can use diagnostic confirmatory questions for each disorder to establish the extent and degree of interference with functionality (severity measures) and provide rapid confirmation of a diagnosis (Tables 1B and 2B). In defining the confirmatory questions for depression, we reached consensus that the physician should also investigate the risk of suicide with 1 screening question.

Table 2B.

Diagnostic Confirmatory Questions for Use by the Physician in Conjunction With the Additional “Optional” Questionnaireb

Many primary care physicians will move from screening directly to treatment, though they may want to consider a specific diagnosis. The consensus view is to go from the screening questionnaire, to confirmation, and then to treatment. The diagnosis is important to patients' understanding of their condition. Without an explanation for the basis of their anxiety, for example, they have no framework for understanding what has happened to them. Not only will patients' fears vary with the particular anxiety disorder, but also the frequency of medical consultation, the patient-physician relationship, family interactions, and appropriate use of support groups. There are also important differences in management considerations. The prognosis differs from one anxiety disorder to another, with consequent differences in the appropriate duration of treatment, what clinical features can be expected to improve with treatment, and the rate of recovery. The appropriate form of psychotherapy will vary, as will the response to secondary therapies such as benzodiazepines and other antidepressants.

We believe that our 2-stage approach of recognition and diagnosis with the core questionnaire will allow primary care physicians to identify at least 90% of the psychiatric disorders in primary care. The use of the additional “optional” questions will allow identification of many of the remaining diagnoses including dysthymia, bipolar disorder, and OCD.

CONSENSUS VIEWS ON MANAGEMENT OF DEPRESSION AND ANXIETY

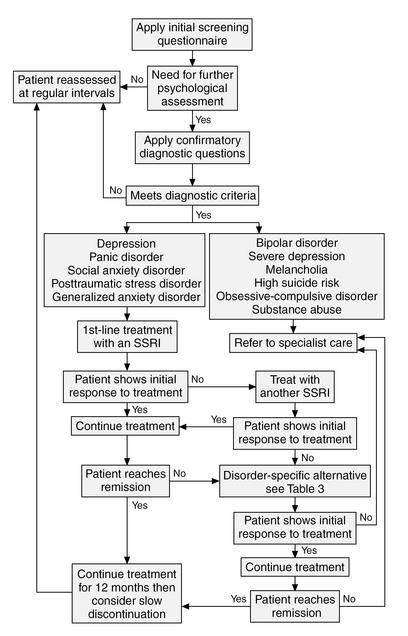

Our approach has been to establish general principles for disease management across the spectrum of anxiety and depressive disorders (Figure 1). In establishing these guidelines, we want to emphasize that the appropriate goal for management is complete remission of symptoms, and treatment should be continued appropriately to try to achieve this target.

Figure 1.

Treatment Algorithm Detailing General Principles for Disease Management Across the Spectrum of Anxiety and Depressive Disorders

Primary Care Guidelines

At this point, we can recommend SSRIs as first-line therapy for the treatment of all depression and anxiety disorders. For example, in panic disorder, treatment should be started with a low dose and that dose increased gradually to the recommended therapeutic level. Benzodiazepine cover may be needed during initiation of treatment of panic disorder. Higher doses of SSRIs (e.g., paroxetine 40 mg) may be needed to achieve a therapeutic effect in panic disorder than in the other anxiety disorders.

Psychotherapy that is proven and specific to the psychiatric disorder may be used instead of, or in addition to, first-line treatment with an SSRI. Cognitive-behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy are the most effective forms of psychotherapy for depression. Cognitive-behavioral therapies with exposure are useful in all the anxiety disorders and are the principal psychotherapies demonstrated to be effective in controlled trials. These psychological treatments are sophisticated techniques and require referral to trained personnel to apply them.

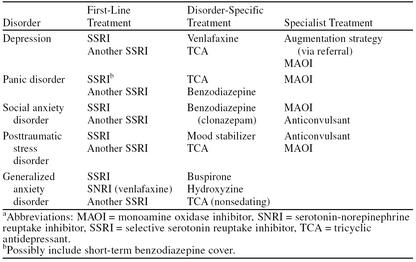

If the response to a trial of first-line therapy is inadequate, we recommend switching to a second SSRI. There is no single alternative second-line treatment applicable to all the anxiety disorders and depression. Disorder-specific alternatives are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Disorder-Specific Treatment Alternativesa

Depression is commonly comorbid with anxiety disorders. The depressed patient with, for example, comorbid social anxiety disorder can be treated with an SSRI and managed in primary care. Where psychiatric disorders are comorbid with certain other conditions, their care can be quite difficult. When depression co-occurs with alcoholism, for example, the primary care physician should consider referral.

Referral Guidelines

Not all cases are appropriate for treatment in a primary care setting, and we would like to draw attention to the situations where there should be referral to specialist psychiatric care or consultation with a specialist.

When screening and initial assessment indicate a high suicide risk, severe depression, melancholia, bipolar disorder, or marked OCD, we recommend immediate referral to specialist care.

When treatment has been initiated in primary care but there is a poor response to therapy, with a failure to attain remission status, or the clinical picture is rapidly deteriorating, we recommend consultation with a psychiatrist or referral to secondary care. Comorbidity that significantly complicates treatment and the need for a complex regimen involving high doses, multiple medications, or therapy with monoamine oxidase inhibitors, for example, are other situations in which the primary care physician should consider inviting specialist opinion. When the patient requires cognitive-behavioral therapy or other specialized psychotherapy not available in primary care, the patient should be referred to a qualified mental health specialist, while control is retained by the general practitioner. Combination therapy may be effective, but there is some evidence that it may be a reason for consultation.56

CONCLUSIONS

Improved recognition and diagnosis of psychiatric disorders is the first step toward an enhanced management of mental health disorders in the primary care setting. We support the use of a simple 2-step procedure consisting of an initial self-report questionnaire, followed by the application of physician-administered diagnostic confirmatory questions.

After diagnosis, we recommend first-line treatment with an SSRI for depression or any of the anxiety disorders. If there is an inadequate response to first-line treatment, we recommend switching to another SSRI. If these are ineffective, there are further effective treatments specific to the various disorders. Combination of first-line or second-line pharmacotherapy with appropriate psychotherapy is recommended, although this must rely on the availability of trained personnel to undertake psychotherapy sessions. Referral and/or consultation with a specialist for diagnostic dilemmas, refractory status, and issues of severity and acuity is recommended.

Drug names: buspirone (BuSpar), clonazepam (Klonopin and others), flumazenil (Romazicon), hydroxyzine (Atarax and others), paroxetine (Paxil), venlafaxine (Effexor).

Footnotes

The meetings convened by the International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety and the subsequent publication of the results of these meetings were supported by an unrestricted educational grant from SmithKline Beecham Pharmaceuticals.

REFERENCES

- Ballenger JC, Davidson JRT, Lecrubier Y, et al. Consensus statement on panic disorder from the International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 8):47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballenger JC, Davidson JRT, Lecrubier Y, et al. Consensus statement on social anxiety disorder from the International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 17):54–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballenger JC, Davidson JRT, Lecrubier Y, et al. Consensus statement on generalized anxiety disorder from the International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 11):53–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballenger JC, Davidson JRT, Lecrubier Y, et al. Consensus statement on posttraumatic stress disorder from the International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(suppl 5):60–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballenger JC, Davidson JRT, Lecrubier Y, et al. Consensus statement on the primary care management of depression from the International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(suppl 7):54–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballenger JC, Davidson JRT, Lecrubier Y, et al. Consensus statement on depression, anxiety, and functional gastrointestinal disorders from the International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 8):48–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballenger JC, Davidson JRT, Lecrubier Y, et al. Consensus statement on depression, anxiety, and cardiovascular disease from the International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 8):24–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballenger JC, Davidson JRT, Lecrubier Y, et al. Consensus statement on depression, anxiety, and oncology from the International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 8):64–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballenger JC, Davidson JRT, Lecrubier Y, et al. Consensus statement on transcultural issues in depression and anxiety from the International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 13):47–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballenger JC. Treatment of panic disorder with serotonin uptake inhibitors (SSRIs). In: Montgomery SA, den Boer JA, eds. SSRIs in Depression and Anxiety. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons. 1998 115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Feighner JP. Overview of antidepressants currently used to treat anxiety disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(suppl 22):18–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, et al. Efficacy of fluvoxamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a double-blind comparison with placebo. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:36–44. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810010038006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chouinard G. Sertraline in the treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder: two double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1992;7:37–41. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199210002-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zohar J, Judge R. Paroxetine versus clomipramine in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;169:468–474. doi: 10.1192/bjp.169.4.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecrubier Y, Bakker A, and Dunbar G. et al, for the Collaborative Paroxetine Panic Study Investigators. A comparison of paroxetine, clomipramine and placebo in the treatment of panic disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1997 95:145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecrubier Y, Judge R. for the Collaborative Paroxetine Panic Study Investigators. Long-term evaluation of paroxetine, clomipramine and placebo in panic disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1997 95:153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballenger JC, Wheadon DE, Steiner M, et al. Double-blind, fixed-dose, placebo-controlled study of paroxetine in the treatment of panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:36–42. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack MH, Otto MW, Worthington JJ, et al. Sertraline in the treatment of panic disorder: a flexible-dose multicenter trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:1010–1016. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.11.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepola UM, Wade AG, Leinonen EV, et al. A controlled prospective, 1-year trial of citalopram in the treatment of panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:528–534. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v59n1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelson D, Lydiard RB, and Pollack MH. et al, for the Fluoxetine Panic Disorder Study Group. Outcome assessment and clinical improvement in panic disorder: evidence from a randomized controlled trial of fluoxetine and placebo. Am J Psychiatry. 1998 155:1570–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin D, Bobes J, and Stein DJ. et al, for the Paroxetine Study Group. Paroxetine in social phobia/social anxiety disorder: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Psychiatry. 1999 175:120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Liebowitz MR, Lydiard RB, et al. Paroxetine treatment of generalized social phobia (social anxiety disorder): a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280:708–713. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.8.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Fyer AJ, Davidson JRT, et al. Fluvoxamine treatment of social phobia (social anxiety disorder): a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:756–760. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.5.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JRT. Pharmacotherapy of social anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 17):47–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocca P, Fonzo V, Scotta M, et al. Paroxetine efficacy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1997;95:444–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb09660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellew KM, McCafferty JP, Iyengar M, and et al. Paroxetine treatment of GAD: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. In: New Research Abstracts of the 153rd Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; May 16, 2000; Chicago, Ill. Abstract NR253:124–125. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall RD, Schneier FR, Fallon BA, et al. An open trial of paroxetine in patients with noncombat-related, chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1998;18:10–18. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199802000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JRT, Malik ML, Sutherland SN. Response characteristics to antidepressants and placebo in post-traumatic stress disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;12:291–296. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199711000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor KM, Sutherland SM, Tupler LA, et al. Fluoxetine in post-traumatic stress disorder: randomised, double-blind study. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175:17–22. doi: 10.1192/bjp.175.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer-Brody S, Connor KM, Churchill EL, et al. Symptom-specific effects of fluoxetine in post-traumatic stress disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;15:227–231. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200015040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk BA, Dreyfuss D, Michaels M, et al. Fluoxetine in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55:517–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe KL, Pitts CD, Ruggiero L, and et al. Paroxetine in the treatment of PTSD: a 12 week, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. In: Proceedings of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies; Nov 16–19, 2000; San Antonio, Tex. Abstract F604. [Google Scholar]

- Thase ME, Simons AD, Reynolds CF III. Abnormal electroencephalographic sleep profiles in major depression: association with response to cognitive behavior therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:99–108. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830020013003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saletu-Zyhlarz G, Saletu B, Anderer P, et al. Nonorganic insomnia in generalized anxiety disorder, 1: controlled studies on sleep, awakening and daytime vigilance utilizing polysomnography and EEG mapping. Neuropsychobiology. 1997;36:117–129. doi: 10.1159/000119373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CF III, Shaw DH, Newton TF, et al. EEG sleep in outpatients with generalized anxiety: a preliminary comparison with depressed outpatients. Psychiatry Res. 1983;8:81–89. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(83)90094-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupfer DJ. Sleep research in depressive illness: clinical implications—a tasting menu. Biol Psychiatry. 1995;38:391–403. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)00295-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunasekara NS, Noble S, Benfield P. Paroxetine: an update of its pharmacology and therapeutic use in depression and a review of its use in other anxiety disorders. Drugs. 1998;55:85–120. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199855010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent PA, Kjaer KH, Bench CJ, et al. Brain serotonin 1A receptor binding measured by positron emission tomography with [11C]WAY-100635: effects of depression and antidepressant treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:174–180. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent NA, Nash J, Hood S, and et al. 5-HT1A receptor binding in panic disorder: comparison with depressive disorder and healthy volunteers using PET and [11C]WAY-100635. Neuroimage. 2000 11Abstract. 189. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado PL, Charney DS, Price LH, et al. Serotonin function and the mechanism of antidepressant action: reversal of antidepressant-induced remission by rapid depletion of plasma tryptophan. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:411–418. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810170011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KA, Fairburn CG, Cowen PJ. Depression relapse after rapid depletion of tryptophan. Lancet. 1997;349:915–919. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)07044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeraldi E, Diaferia G, Erzegovesi S, et al. Tryptophan depletion in obsessive-compulsive patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;40:398–402. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00393-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr LC, Goodman WK, McDougle CJ, et al. Tryptophan depletion in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder who respond to serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:309–317. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950040053007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forshall S, Bell C, Nutt D. Relapse of panic symptoms after rapid depletion of tryptophan. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2000;3:S228. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Linzer M, et al. Health-related quality of life in primary care patients with mental disorders: results from the PRIME-MD 1000 Study. JAMA. 1995;274:1511–1517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Leon AC, Broadhead WE, et al. The SDDS-PC: a diagnostic aid for multiple mental disorders in primary care. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1995;31:415–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg D, Williams P. A Users Guide to the General Healthcare Questionnaire: GHQ. 1988. Windsor, UK: NFER-NELSON. 1991 [Google Scholar]

- Zich JM, Attkisson CC, Greenfield TK. Screening for depression in primary care clinics: the CES-D and the BDI. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1990;20:259–277. doi: 10.2190/LYKR-7VHP-YJEM-MKM2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecrubier Y, Sheehan DV, Weiller E, et al. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): a short diagnostic structured interview: reliability and validity according to the CIDI. Eur Psychiatry. 1997;12:224–231. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) according to SCID-P and its reliability. Eur Psychiatry. 1997;12:232–241. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 20):22–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Üstün TB, Sartorius N. eds. Mental Illness in General Health Care: An International Study. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The Primary Health Care Version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview: CIDI-PHC. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 1991 [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D. Depression and anxiety spectrum disorders. Presented at the 22nd meeting of the Collegium Internationale Neuro-Psychopharmacologicum; July 9–13, 2000; Brussels, Belgium. [Google Scholar]

- Lecrubier Y, Bobes J, Gutierez M, and et al. Validation of the MINI in four European countries. Eur Psychiatry. In press. [Google Scholar]

- Ballenger JC. Current treatments of the anxiety disorders in adults. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:1579–1594. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00220-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]