Abstract

The primary care physician has a vital role in documenting and preventing sexual abuse among the mentally retarded populations in our community. Since the current national trend is to integrate citizens with mental retardation into the community away from institutionalized care, it is essential that all physicians have a basic understanding of the unique medical and legal ramifications of their clinical diagnoses. As the legal arena is currently revising laws concerning rights of sexual consent among the mentally retarded, it is essential that determinations of mental competency follow national standards in order to delineate clearly any instance of sexual abuse. Clinical documentation of sexual abuse and sexually transmitted disease is an important part of a routine examination since many such individuals are indeed sexually active. Legal codes adjudicating sexual abuse cases of the mentally retarded often offer scant protection and vague terminology. Thus, medical documentation and physician competency rulings form a solid foundation for future work toward legal recourse for the abused.

Mentally retarded individuals in the United States are increasingly integrated into the community away from institutionalized care. Because primary care physicians are uniquely positioned in our society to identify and to prevent sexual abuse among these individuals, these health professionals must understand the possible medical and legal consequences of their clinical diagnoses in this population.

MEDICAL ANALYSIS

This section familiarizes the primary care physician with the current professional standards implemented nationally by physicians and psychologists to assess cognitive ability and ability to consent to sexual activity. In addition, medical perspectives on pertinent aspects of sexual development of mentally retarded individuals and profiles of the typical perpetrators of sexual abuse are provided as a reference for the practicing physician.

Profile of Individuals With Mental Retardation

Individuals with mental retardation fall within a spectrum of abilities, characteristics, and personal attributes, as is seen in any general population. However, mentally retarded individuals have developmental delays in learning, processing information, and independently caring for themselves. Such individuals show marked delays in adaptation to a changing environment. Yet even so, nearly 85% of these individuals are able to live successfully in the community.1

The quest to find accurate terminology describing this group of individuals has been historically fraught with sensitivity and intense debate. This article uses the standard terms mentally retarded individual or the mentally retarded, both of which are in accordance with the terminology used by both the American Medical Association (AMA) and the American Association on Mental Retardation (AAMR), a strong advocacy group for this population.

The reader should note that the term developmentally disabled denotes a broader category that encompasses those with mental retardation, cerebral palsy, epilepsy, autism, or other neurologic conditions closely related to mental retardation.2 Likewise, terms such as mentally defective, imbecile, cretin, and mongoloid, although still found in state statutes and medical texts, are considered offensive by modern standards.

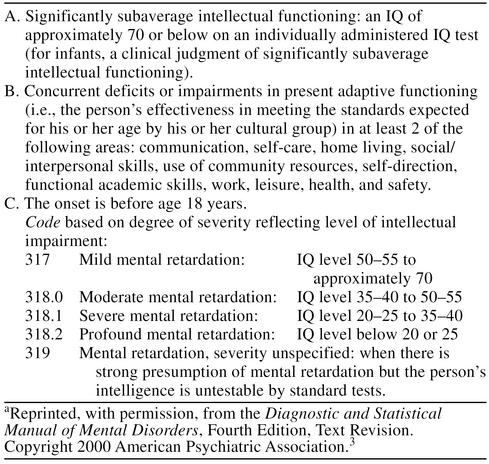

Medical Classification of Mental Retardation: Three Required Criteria From DSM-IV-TR

The AMA follows the 3 criteria set forth by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) to diagnose mental retardation, as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR)3 diagnostic criteria for mental retardation (Table 1).

Table 1.

DSM-IV-TR Diagnostic Criteria for Mental Retardationa

First, an individual's intelligence level is usually determined as an intelligence quotient (IQ) by a licensed examiner using 1 of 4 standard examinations. The Stanford-Binet Scale was the first formal IQ test developed in 1905 and has historically been used to assess those aged 2 to 18 years. Today, it is employed for children below the age of 6, the cognitively impaired, or the extremely gifted.4 The Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Revised, is used to assess children and teenagers 6 to 17 years of age. The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Revised, is used for adults, aged 17 years and above. The Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence is the most recent modification and is used to assess children 4 to 6 years of age.4–6 The total IQ score is derived from the verbal score added to the performance score. Average IQ score is 100, with a normal IQ range in the population varying from 70 to 130.6,7 It has been shown repeatedly that IQ is quite stable from the age of 5 years onward.4

There are 2 methods of scaling IQ, the deviation from the means method and the mental age method. The AMA and APA use the deviation from the means method, and an individual's IQ must be at least 2 standard deviations below the mean to be classified as mental retardation. Approximately 2.5% of any national or state population will show an IQ in this range of less than 70. Even today, the standard method used by states to estimate its mentally retarded population is simply to take 2.5% of its total population census. The mental age method can also be used to quantify IQ. Mental age (MA) is used to describe a person's intellectual level in terms of what would be expected at a certain chronological age (CA) in a nonretarded individual. That is, if a test taker is 15 years old (CA = 15) but achieves the same test score as would be normal for someone 8 years old, then (MA/CA) × 100 = IQ, so (8/15) × 100 = IQ of 53, which falls in the mentally retarded range. As with any standardized test, differences in culture, environment, and language may bias results. Furthermore, intelligence level tests are only part of the diagnosis; sole reliance on IQ or mental age is an inadequate classification of mental retardation.7

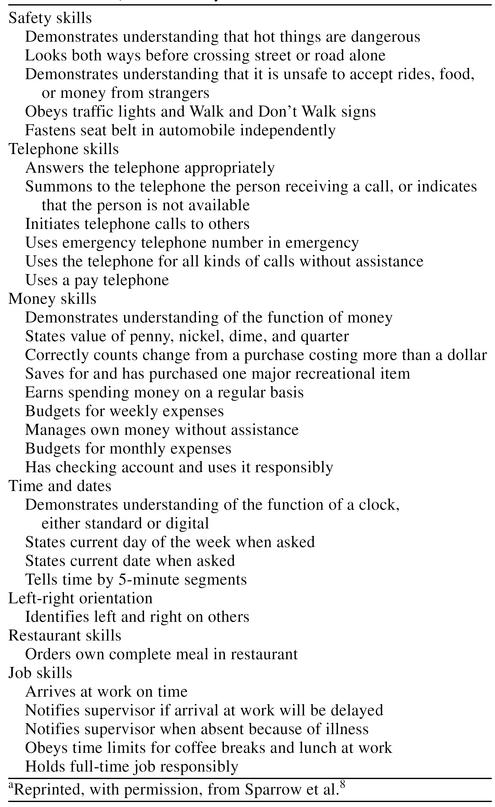

Second, the adaptive functioning of an individual is an evaluation of his or her ability to fulfill the daily activities necessary for self-sufficiency.7 It can be measured either with direct observation, with a standardized test such as the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, or with both techniques8 (Table 2). Unlike the IQ test, which is given in one setting, this evaluation may require several observations and several examiners to compile a composite of the individual's functioning. In addition to a subaverage IQ, the individual must have a deficit in at least 2 of the 11 DSM-IV-TR Section B skill categories: communication, self-care, home living, social/interpersonal skills, use of community resources, self-direction, functional academic skills, work, leisure, health, and safety.7 Because the majority of the mentally retarded are educable, their deficits in adaptive functioning are amenable to positive improvement with proper education.7 Mentally retarded individuals have been shown to gain adaptive functioning skills in areas in which they were once deficient.9 Generally, these adaptive behaviors improve over the course of a lifetime.7

Table 2.

Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales: Daily Living Skills Domain, Community Subdomaina

Third, since mental retardation is defined as a disruption of a child's developmental process, onset must occur before the age of full mental development, i.e., before 18 years of age.6 The cognitive development of a mentally retarded individual initially follows the same biological sequence as that of a nonretarded individual and is therefore described as nondeviant cognitive development.6 Although development is nondeviant, the mentally retarded individual develops at a slower rate and is prematurely arrested in development at a suboptimal level.10 This stalled cognitive development leads to varying degrees of impairment of intelligence and adaptive skills. Thus, a biological ceiling is placed on the person's ultimate level of achievement.11 By contrast, if a fully developed cognitive adult with an IQ above 70 later becomes impaired in intelligence, adaptive skills, or both, he or she is classified not as mentally retarded but as having dementia.6 Because such an adult had a normal developmental process, as evidenced by a normal IQ, such a reversal does not qualify for the definition of mental retardation.

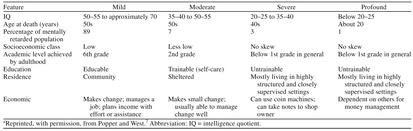

Four Categories of Mental Retardation

Based on the aforementioned standards set forth by the APA, mental retardation is classified into 4 categories: mild, moderate, severe, and profound mental retardation6,7,10 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical Features of Mental Retardationa

Mild mental retardation is the most common category and is typified by an IQ of 50–55 to 70. Approximately 85% of mentally retarded individuals are classified as mildly retarded.7 In keeping with professional opinion that the environment can both positively and negatively affect a child's mental development, it is documented that mild retardation is more prevalent among lower socioeconomic groups.7 A mildly retarded individual is able to be educated up to the 6th-grade level and thus can obtain vocational training. As such, these individuals are usually capable of maintaining a steady job and living in the community.12 With varying degrees of social and communication skills, such mildly affected individuals are able to live in the community with minimal supervision.7 Since it is possible for mildly retarded individuals to be out in the community working and interacting with others with a high degree of personal freedom, this group is the most likely to have real issues regarding sexual activity, including sexual consent, assault, and abuse.

Moderate mental retardation is the second most common category, accounting for 10% of cases of mental retardation, and is associated with an IQ range of 35–40 to 50–55.6,7 These individuals usually are not able to maintain a job but are able to perform some tasks, such as manipulating basic monetary exchanges.3 Their highest education level attainable is approximately 2nd grade.7 Although not considered educable, this group is considered trainable in the area of self-care, daily living skills, and basic vocational skills.3 Yet, often these functionally adaptive and communicative abilities are a facade, since this group has particular difficulty processing abstract information.7

Severe mental retardation is the third most common category, accounting for 3% of cases of mental retardation, and is associated with an IQ range of 20–25 to 35–40. These individuals are capable of minimal daily functions and are very dependent on a structured and supervised setting. The highest educational level achieved is below the 1st grade, and the group is considered not educable.7

Profound mental retardation is rare, accounting for 2% of cases of mental retardation, and is characterized by an IQ below 20 to 25.7 These individuals often have major central nervous system disorders, sensory handicaps including deafness and blindness, and severe motor and physical disabilities such as cerebral palsy and allied seizure disorders.10 Like the severely mentally retarded, the highest educational level achieved is below the 1st grade, and the group is also considered not educable.7,10

Even though these 4 categories of mental retardation have served as the standard for diagnosis, in 1992 the AAMR changed its definition of mental retardation for the increased numbers of individuals interacting with the community at large. This new classification includes 4 levels of support: intermittent, limited, extensive, and pervasive. These AAMR classifications roughly parallel the 4 standard AMA/APA categories.

Mental Retardation Etiologies

Common etiologies of mental retardation include chromosomal abnormalities, congenital infections, teratogens (toxic chemicals including drugs and/or alcohol), malnutrition, radiation, and unknown conditions affecting implantation and embryogenesis.13

Approximately 25% of mental retardation cases are attributed to a specific biomedical cause, while the other 75% have no identifiable cause.11 It is interesting to note that 90% of mentally retarded infants are born from nonretarded parents, thus scientifically debunking the eugenics myth.14 Of total cases of mental retardation, 15% have genetic origin.12 Approximately 35% of cases are attributable to environmental origin, including brain injury, infection, accident, or premature birth.14 Of moderate and severe cases of mental retardation, 90% are due to prenatal conditions, such as genetic disorders, drug abuse, intrauterine chemical exposure, and infections.11

It is important to note that mental retardation is often associated with other bodily differences, i.e., differences in medication metabolism rates, certain kinds of seizures, and certain heart malformations. The physician should be alert to any signs often associated with mental retardation, including hypotonia, hepatosplenomegaly, coarse facial features, abnormal urinary odor, a large tongue, an overly large or small head, delays in sitting or walking, or a delay in pincer grasp, among others.13

Due to increased genetic counseling, amniocentesis screens, the rubella vaccine, and state-mandated testing for some genetic metabolic disorders, the incidence of mental retardation is actually decreasing. Yet, because of technological advances that sustain infants with very low birth weight, the prevalence of mental retardation is considered to be constant.13

Sexual Maturation and Fertility of the Mentally Retarded

The onset of puberty varies widely among mentally retarded individuals, and sexual development of the retarded may be reached at a later chronological age.15 The majority of the mentally retarded develop normal secondary sexual characteristics but need more help in understanding these changes. It is now recognized that sexual interests and desires of the mild and moderately retarded vary in intensity just like those in the nonretarded population.15,16 According to a 1982 article in Pediatric Annals, the “mentally retarded adolescent is a sexual being, whose reproductive ability, sexual interests, and sexual activity range from high to low,”17(p848) identical to the range in the general population.17 However, parents, special education instructors, and institutions open the door to abuse by shying away from any biological instruction either from a misplaced sense of propriety or an unawareness of the importance of such instruction in preventing sexual abuse. Thus, ideas of proper sexual conduct are shaped by unreliable influences from the media, peer groups, caretakers with impure motives, or other perpetrators of sexual abuse.

The mentally retarded show a lower rate of offspring production than the nonretarded, yet the majority of mentally retarded individuals are potentially fertile with margins for individual variation.10 The American Journal of Mental Retardation documents that the risk of producing mentally retarded offspring is as follows: 40% when both parents are mentally retarded, 15% when one parent is mentally retarded, and 1% when both parents are not retarded.9 Although having children is a social and economic complication, forced sterilization of individuals with mental retardation was deemed inhumane in the 1940s when the dangers of an overzealous eugenics movement were revealed by World War II atrocities.2

Since the sexual behavior and moral outlook of mentally retarded individuals are learned and reinforced by their environment, parents, educators, and institution and group home staff have a pivotal role in shaping these minds.9 While the literature maintains that mentally retarded persons are capable of sustaining “reasonable, stable, and happy marriages” and that marriage often provides a stable and supportive environment for companionship and care, many parents and professionals still view the mentally retarded individual at extremes ranging from “childlike” to “overly sexed.”12,16 Thus, ignorance of the mentally retarded about their own sexuality persists due to the hesitance of parents and institutional staff to broach these issues; such ignorance of sexual matters has been suggested to make the mentally retarded individual ironically more vulnerable to sexual abuse.18 Thus, basic sexual abuse prevention education for both incoming caregivers and sexually mature clients is a crucial component for preventing sexual abuse among the mentally retarded. The physician is encouraged to fulfill an advocate's role by broaching the issue of sexual activity with the patient and directing the patient and caregiver toward community resources and support groups to address these issues.

Mental Retardation Versus Mental Illness

Mental illness is separate from but can coincide with mental retardation. There is an approximately 2-fold increase in psychopathology among mentally retarded persons.10 Thus, even with a nonuniform use of psychiatric diagnostic classification, the mentally retarded still have a high incidence of psychiatric disorders. Physicians should be aware that many such individuals may be taking psychoactive medications.10

Abuser Profile

Mentally retarded individuals are especially vulnerable to abuse and exploitation. It is estimated that these individuals are victimized at 4 to 10 times the rate of the general population.2 Studies document that between 25% and 85% of the mentally retarded are victims of sexual abuse; such a variance in percentage underscores the clandestine and subtle nature of such abuse.7,12,19 Furthermore, Sobsey20 estimates that between 15,000 and 19,000 individuals with developmental disabilities experience rape each year. There are several reasons why mentally retarded individuals are especially prone to sexual abuse, the most significant of which is the ingrained reliance on the caregiver authority figure.12,17,19,21 Emotional and social insecurities, ignorance of sexuality and sexual abuse, and powerless position in society have been noted as further causes of frequent exploitation.18 Additionally, it has been documented by several sources22–25 that mentally retarded persons are often prime victims for abuse due to naïveté and an underlying need to be accepted by peers. Such abuse is often extensive and ongoing. As Craft and Craft concede, “mentally handicapped individuals tend to be nonassertive and to agree to participate in sexual acts if directed to do so, possessing poor judgement in assessing other people's motives.”26(p497)

The sexual abuse offender is most likely to be known and trusted by the mentally retarded victim.17 According to Sobsey and Doe's 1991 analysis of 162 reports of sexual abuse against people with disabilities, the largest percentage of offenders (28%) were service providers (direct care staff members, personal care attendants, psychiatrists).22 In addition, 19% of sexual offenders were natural or step-family members, 15.2% were acquaintances (neighbors, family friends), 9.8% were informal paid service providers (baby-sitters), and 3.8% were dates.22 Further, 81.7% of the victims were women, and 90.8% of the offenders were men.22

Thus, a primary care physician should not rely entirely on family members or caretakers to provide an accurate account of the mentally retarded patient's sexual history. A thorough examination may reveal bruising or infection in the genital area. Thus, it is crucial to document and report any irregularities as early as possible since such sexual abuse is often part of a wider pattern that may also affect other mentally retarded individuals.

Informed Consent Versus Competency

Medical consent is understood in the context of the classic doctrine of “informed consent.” Such informed consent is a constant companion to the primary care physician and takes a central role in situations ranging from routine physician-patient encounters to complicated surgeries. The informed aspect includes understanding information as to the nature of the procedure, the risks and benefits of the procedure, and alternative courses of action. The consent aspect includes the voluntary and autonomous nature of the patient's decision.27

Informed consent has 5 main components of understanding: the nature, purpose, risks, and benefits of a procedure and the alternatives to a procedure. There are 4 recognized exceptions to the doctrine of informed consent: case of emergency (used in emergency room settings), patient waiver, therapeutic privilege (unconscious or incapacitated patient), and inadequate competency (minors unless emancipated by marriage but not pregnancy). States vary for ages of consent to birth control and abortion.4

In routine encounters there exists a certain loose standard, called a “transparency” standard of consent, in daily medical practice.28 With complicated procedures or complicated mentally retarded patients, such consent still is valid to obtain but presents a greater challenge to procure.

As Coulehan and Block27 emphasize repeatedly, informed consent is a process of informational internalization and not just a scribbled patient signature on a piece of paper. Even in the court of law, such a signed document may serve as evidence of informed medical consent but still can be inadequate by itself to prove full consent.27

Medical consent is primarily an issue of communication of the risks, benefits, and alternatives of a proposed medical treatment. Such consent is contextual in that the setting of questions and answers is most pertinent to the quality of the patient's understanding and agreement. As Coulehan and Block describe, “The important issue here is that consent must be obtained in the context of a conversation during which clear explanations are given and questions are answered, and the patient's competence and understanding are assessed.”27(p271)

Medicine can claim the doctrine of informed consent as its own. By contrast, the concept of competency belongs to the legal realm. Competency is the individual's ability to make rational, informed decisions concerning oneself or one's property.21 There is no “medical competency” per se, only the legal competence to make medical decisions. A competent individual is able to give informed consent.18 Courts often rely on a physician's medical evaluation to determine the mental capacity to make legally competent decisions regarding medical care or sexual encounters, but “medical competency” is never established as an existing entity. For example, a patient in a state of coma, unconsciousness, or severe dementia is generally deemed to be incompetent to make medical decisions. A mentally retarded individual, however, may demonstrate adequate processing skills to be able to make rational decisions regarding sexual activity and thus qualify as competent for such an activity. Thus, it must be emphasized that competence is a legal concept and is not a medical concept.27 As Michael G. Farnsworth, M.D., a practicing psychiatrist, notes, “A medical opinion of incompetency, regardless of the source, remains only an opinion until a judicial ruling on the evidence is given.”21(p182)

The 1982 Presidential Commission on Ethical Decisions in Medical and Health Care proposed 3 core elements of competency: a possession of a set of values and goals, the ability to communicate and understand information, and the ability to reason and deliberate.1 Thus, it is the individual's process of decision making, rather than the choosing of a specific outcome, that determines competency.27

Competency is decided subjectively on a case-by-case basis; that is, there is no absolute IQ designation for an individual to be positively assessed for competency to consensual sexual activity. Also, competency is not absolute for all actions; for example, an individual may be assessed as competent for daily living tasks but deemed incompetent for consensual sex.

In helping to determine legal competency, a physician or psychologist generally asks a series of questions or utilizes one of several competency assessment tests to probe the individual's various neurologic, psychological, intellectual, and physical capacities to make an informed decision. To date, no one test has emerged as providing superior criteria with which to determine the competency of a mentally retarded individual for sexual activity. Because a standard assessment test is neither devised nor universally accepted, the question of decisional competency is currently resolved by analyzing the various components of mental competency.

By nature of the ongoing relationship with the patient, the primary care physician is arguably better positioned than the psychiatrist or psychologist specialist to assess mental competency of the mentally retarded individual. Farnsworth, in a 1989 article,21 set up a valuable algorithm for use in the primary care setting. The primary care physician is able to assess competency by assessing the 3 main aspects as follows: awareness of the nature of the situation, an understanding of the issue at hand, and the ability to use information rationally to arrive at a decision.21 If, during the conversation, the physician deems the patient capable of all 3 categories, then the opinion of competency can be confidently proclaimed. If there are serious deficits in understanding these 3 main criteria, then the primary physician is fully qualified to prepare the proper documents for the court, including relevant descriptions of the patient and opinions from family members, occupational therapists, psychologists, and other observers.21

Ideas forming the concepts of informed consent and competency are also pertinent to the legal arena, as will be shown in the following legal analysis of the ramifications of sexual abuse among mentally retarded individuals.

LEGAL ANALYSIS

Laws protecting the mentally retarded individual across the nation are consistently characterized by both medical and legal scholars alike as vague, inconsistent, and inadequate in their protection of vulnerable individuals from sexual abuse. Yet, there are 6 main legal “tests” currently implemented by courts across the nation to assess legal consent to sexual activity; these tests at least provide a common ground for analysis.

The following few paragraphs will discuss current laws on sexual abuse and will define the legal terminology employed by such statues and codes. Finally, medicine's role in the courtroom will be elucidated with recommendations to the primary care physician on how to play an advocate's role in the clinical setting.

Sexual Abuse and the Law

Cases of sexual abuse are considered in many states to qualify as “sexual assault” under the law; sexual assault is often arbitrated through rape or sexual battery statutes. Cases of sexual assault are arbitrated differently according to individual state laws and statutes; however, there are 3 main themes that may prove helpful for the physician.

First, states often have statutes for the mentally retarded citizen separate from the general sex offense statutes. Such separate statutes often hold the retarded citizen at a “higher standard” than the nonretarded citizen; that is, the legal standards used to prove sexual consent will be stricter for the retarded individual. Such a separation was originally intended to protect the mentally retarded citizen but in practice has proven to isolate the victim, invoke stereotypes, and impede prosecution of sexual abuse cases.2

Second, despite attempts to standardize and refine sexual assault law, legal terminology and legal tests remain as crude implements in adjudicating sexual assault cases among the mentally retarded. State court guidelines have evolved not from a comprehensive, well-designed plan but from a series of court decision precedents; thus, comprehensive legal protection for the mentally retarded individual is nearly nonexistent. As Deborah W. Denno, Ph.D., J.D., of the Fordham University of Law eloquently explains, “courts have applied vague, unworkable tests in determining a mentally retarded victim's capacity to consent; it would be unrealistic to suggest that a rigid, precisely defined standard could ever be effective in so amorphous an area as sexual relations.”2(p434) Denno espouses a “contextual approach,” which is remarkably medical in its basis. Her approach would use modern biological knowledge of the developmentally delayed as a basis for consent determination according to the particular context of alleged abuse. Yet, despite the acknowledged difficulties in writing adequate sexual abuse case law, state courts must work with some kind of standard.

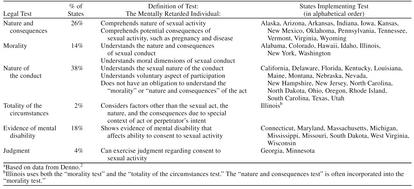

Third, 6 major tests are used as such a standard to assess the legal capacity of the mentally retarded individual to consent to sexual conduct.2 These are the tests of “nature and consequences,” “morality,” “nature of the conduct,” “totality of the circumstances,” “evidence of mental disability,” and “judgment.” The 50 states across the nation, with the exception of Illinois, use 1 of these 6 tests in reviewing cases of sexual abuse (Table 4).

Table 4.

National Legal Tests to Determine Sexual Consent for the Mentally Retarded Individuala

The majority of states in the nation (19 states, or 38% of the nation) currently implement the “nature of the conduct test”: California, Delaware, Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Texas, and Utah. This test necessitates understanding the sexual nature of any sexual conduct and the voluntary aspect of such activity. In sharp contrast to the medical informed consent doctrine, there is no obligation to understand the nature and consequences of such sexual activity, nor is there any obligation to comprehend the morality of the act.

The “nature and consequences test” is employed by 13 states (26% of the nation): Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Vermont, Virginia, and Wyoming. This test is remarkably similar to the medical informed consent doctrine in which the patient must understand both the nature and consequences of a procedure; this test also parallels the medical consent doctrine in that the individual must understand the risks of behavior, including negative outcomes.

The “morality test” is employed in a group of 7 very geographically, politically, and socially diverse states (14% of the nation): Alabama, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, New York, and Washington. This test necessitates a moral understanding of the sexual activity in addition to understanding the nature and consequences of sexual conduct.

The “totality of the circumstances test” is unique to Illinois, which recently employed this test in addition to its previously existing morality test. The “evidence of mental disability test” is not a statute per se but a method that allows for the court to consider evidence of disability. Nine states (18% of the nation) use this method: Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, South Dakota, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. The “judgment test” is unique to Georgia and Minnesota and simply ascertains whether the individual can exercise judgment regarding consent to sexual activity.

Defining Legal Consent

Legal consent, like medical informed consent, is greatly influenced by the context of the incident in question. However, in contrast to the doctrine of informed consent, legal consent to sexual activity is by far a more subjective and elusive concept with greater variance from state to state. One reason for this is that the underlying players, the mentally retarded individuals, are marked by “situational variations in their capacity to consent and the evolving nature of their condition.”2(p147)

The 6 national legal tests addressed earlier are a good beginning in the challenge to categorize legal consent. As was established, states will greatly vary in their definitions of legal consent with respect to the mentally retarded citizen; however, Stavis and Walker-Hirsch,1 under the auspices of the AAMR, propose 3 helpful standards of legal consent that are upheld by most advocacy groups as ideal. Their 23 dimensions can be summarized in 3: knowing relevant facts concerning the proposed activity, having the ability for rational processing of the risks and benefits of such behavior, and understanding the voluntary nature of the action.1 Medical consent themes of risk, benefit, noncoercion, and alternatives surface once again in legal consent doctrine.

Defining Competency Versus Capacity

As discussed earlier, competency is a legal concept, but primary care physicians are both able and uniquely positioned to submit opinions for the court's final determination. There is no central agency within special education or training programs that marks a mentally retarded individual as “competent” or “incompetent” for sexual encounters. Competency or incompetency is determined as the situation arises.

While incompetency denotes a legal inability to make rational, informed decisions, incapacity is a more expansive legal term that denotes ineligibility and inability regarding basic life decisions.1 Competency can be legally partitioned into either general competency (general ability to handle one's life) and specific competency (clinically used to assess specific life tasks). Likewise, incapacity can be divided into global incapacitation and limited/specific incapacitation. Although, predictably, state laws governing the finding of incompetency and incapacity are both vague and varied, generally there are provisions to establish a guardianship or conservatorship in the case of a ruling of incompetence.21

The Role of Medicine in the Courtroom

The scientific medical community traditionally has had several significant roles in courtroom proceedings of cases of sexual abuse among the mentally retarded. These roles lie predominately in the areas of IQ, opinions of competency, and sexual history documentation.

The IQ of the alleged victim has historically formed the cornerstone of presentations by both the prosecution and the defense. The numerical IQ is used in the courtroom as a key instrument to either establish or disprove competency and the independent social and sexual functioning of the mentally retarded individual in question. Because IQ is such a powerful psychological assessment, it is crucial that the medical professional pay special attention to establish its accuracy. Further, because of the aforementioned shortcomings of any IQ testing, it is crucial that any strengths and weaknesses outside of the test be documented adequately. The physician should also note that the concept of mental age is falling out of favor with the legal community because it assumes a static state of development inconsistent with the documented ability of the mentally retarded to learn, adapt, and develop, albeit at a slower pace. Further, labeling an individual with a “mental age” of “7” egregiously omits the biological fact that such a person may have the sexual development present in a nonretarded person of 19 years of age.2 Thus, “mental age” belies “physical age.”

Providing opinions regarding competency in terms of determining the capacity of the patient to consent to sexual relations is another key role of the medical professional. Documentation of ability to perform household or daily living tasks, such as the 10 AAMR-designated adaptive skill areas, can provide key evidence for the court. Courts will often admit physicians' opinions of competency and mental functioning as evidence to support or to deny ability to give legal consent to a sexual encounter. Thus, medical competency opinions often profoundly affect legal competency rulings. Also, physicians may serve as expert witnesses in the courtroom to provide professional insight into the mental and emotional status of an individual in question.

Medical sexual history documentation is a crucial area no longer immune to the eyes of the court; medical records have been recalled and even used against the victim. One prominent example often cited by legal scholars is the Glen Ridge rape case in which a young mentally retarded woman by the name of Betty Harris was victimized.29 In an effort to prove sexual promiscuity, the defense recalled medical records which revealed that Ms. Harris was taking regular birth control pills. Although in this case it was resolved that oral contraception was a means to protect the patient from pregnancy after several instances of sexual abuse, the case underscores the importance that the primary care provider recognize the possible consequences of sexual history and activity documentation. It is crucial to protect the patient by providing adequate documentation of preventative pregnancy measures and noting where applicable the absence or presence of regular sexual activity and/or signs of sexual abuse.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PRIMARY CARE PHYSICIANS

Physicians have a potentially powerful role in preventing and documenting cases of sexual abuse among the mentally retarded in their communities. First, medical professionals must always be keenly observant for signs of sexual abuse or sexual activity during clinical visits. It is essential that community physicians realize that the mentally retarded can be sexually active within a consensual setting and thus require adequate counseling and testing concerning sexually transmitted diseases. Since the majority of sexually abused mentally retarded individuals are women, there is a great need to counsel and/or prevent a possible pregnancy. A thorough examination is crucial to document sexual abuse and to prevent the spread of disease. The physician should be aware that the mentally retarded in community group homes can become easy targets for abuse by caretakers or other members of the community, since the majority of abusers are known to the individual. Thus, physicians must be courageous to inquire about sexual activity and to report any irregularities. It is helpful to remember that the physician may justifiably breach confidentiality in the cases of reportable infectious diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, cases of child abuse, and cases of threat of harm to self or others (suicide or homicide).4 Clinical documentation must be clear and honest, since it can serve as key evidence in a court proceeding for either the defense or the prosecution. A clinically documented case of sexual abuse involving a mentally retarded individual has the potential for strong legal action in the future.

Second, medical professionals shoulder an awesome responsibility in determining IQ and mental age assessments. Such scores will categorize an individual and must be done accurately to assist in proper social and educational development. IQs can be detrimentally used in court if not accompanied by sufficient documentation of strengths and weaknesses excluded by the standardized test.

Third, the primary care physician is legally able and medically ideal to assess opinions of medical competency for a court's final review. Physicians in general have a designated responsibility to determine opinions of mental competency and expert testimony for sexual abuse cases. They must be clear and thorough in their diagnosis and mindful that their decision will impact court rulings and future legal precedents.

Fourth, the primary care physician should have contact information available for mentally retarded patients needing further education and counseling on sexual issues. Such education to resist potential abusers empowers the mentally retarded individual and will greatly facilitate communication about sexual abuse cases in both the medical and legal settings.

MEDICOLEGAL CONCLUSIONS

Physicians have the great responsibility of serving alongside the legal court as 1 of the 2 essential pillars of sexual abuse defense among the mentally retarded. The primary care physician in particular serves an important role in cases of sexual abuse by providing the court with physical evidence of abuse and by documenting opinions of mental competency. Medical and legal analysis of terminology pertinent to sexual abuse reveals that both professions recognize a contextual element of consent and emphasize the importance of the ability of the mentally retarded individual to understand the nature and consequences of any sexual activity.

It is imperative for physicians to understand the biological aspects of mental retardation in order to make informed decisions concerning the rights of the mentally retarded in the community. It is crucial for physicians to recognize that mentally retarded citizens, from childhood to adulthood, have a unique biological profile that makes them particularly vulnerable to sexual abuse.

Knowledgeable primary care physicians in the front lines in our community are in a unique position to detect and prevent such sexual abuse, ideally before the case even reaches the courts. With the rapidly changing demographics of the mentally retarded population across the country, it is crucial to raise awareness among primary care physicians in order to identify and stop cases of sexual abuse.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges Pamela D. Connor, Ph.D., whose support made this publication possible.

Footnotes

Ms. Morano is a candidate for a degree in Medicine at the University of Tennessee, Memphis.

The research conducted for this publication was initially undertaken at the direction of the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation's Medicaid Fraud Control Unit (MFCU) by a team of medical, legal, and pharmacy students involved in an internship program during the summer of 2000. The Tennessee Bureau of Investigation has not exercised editorial control over the contents of this publication; thus, the opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions, position, or policies of the MFCU or the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation.

REFERENCES

- Stavis PF, Walker-Hirsch LW. Consent to sexual activity. In: Dinerstein RJ, Herr SS, O'Sullivan JL, eds. A Guide to Consent. Washington, DC: American Association of Mental Retardation. 1999 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Denno DW. Sexuality, rape, and mental retardation. University of Illinois Law Review. 1997;720:315–434. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Compass Medical Education Network. Behavioral Science Review. Chicago, Ill. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, Black D. Introductory Textbook of Psychiatry. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- Ames TH, Samowitz P. Inclusionary standard for determining sexual consent for individuals with developmental disabilities. Ment Retard. 1995;33:264–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popper C, West SA. Disorders usually first diagnosed in infancy, childhood, or adolescence. In: Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, Talbott JA, eds. The American Psychiatric Press Textbook of Psychiatry. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. 1999 884–887. [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow SS, Balla DA, and Cicchetti DV. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales. In: Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, Talbott JA, eds. The American Psychiatric Press Textbook of Psychiatry. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. 1999 772–783. [Google Scholar]

- Abramson PR, Parker T, Weisberg SR. Sexual expression of mentally retarded people: educational and legal implications. Am J Ment Retard. 1988;93:328–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menolascino FJ, Levitas A, Greiner C. The nature and types of mental illness in the mentally retarded. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1986;22:1060–1071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntley CF, Benner SM. Reducing barriers to sex education for adults with mental retardation. Ment Retard. 1993;31:215–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pincus S. Sexuality in the mentally retarded patient. Am Fam Phys. 1988;37:319–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beers MH, Berkow R. eds. The Merck Manual. 17th ed. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck Research Laboratories. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- Saunders EJ. The mental health professional, the mentally retarded, and sex. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1981;32:717–721. doi: 10.1176/ps.32.10.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonds JF. Sexual behaviors in retarded children and adolescents. Dev Behav Pediatr. 1980;1:173–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders EJ. Staff members' attitudes towards the sexual behavior of mentally retarded residents. Am J Ment Def. 1979;84:206–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DM, Johnson WR. Sexuality and the mentally retarded adolescent. Pediatr Ann. 1982;11:847–853. doi: 10.3928/0090-4481-19821001-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furey EM. Sexual abuse of adults with mental retardation: who and where. Ment Retard. 1994;32:173–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisel A, Roth LH, Lidz CW. Toward a model of the legal doctrine of informed consent. Am J Psychiatry. 1977;134:285–288. doi: 10.1176/ajp.134.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobsey D. Violence and Abuse in the Lives of People With Disabilities: The End of Silent Acceptance? Baltimore, Md: Paul H. Brooks Publishing Co. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Farnsworth MG. Evaluation of mental competency. Am Fam Phys. 1989;39:182–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobsey D, Doe T. Patterns of sexual abuse and assault: sexual exploitation of people with disabilities [special issue] Sexuality and Disability. 1991;9:243–259. [Google Scholar]

- Lumley VA, Miltenberger RG. Sexual abuse prevention for persons with mental retardation. Am J Ment Retard. 1997;101:459–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aylott J. Preventing rape and sexual assault of people with learning disabilities. Br J Nurs. 1999;8:871–876. doi: 10.12968/bjon.1999.8.13.6560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tharinger DT, Horon CB, Millea S. Sexual abuse and exploitation of children and adults with mental retardation and other handicaps. Child Abuse Neglect. 1990;14:301–312. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(90)90002-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft A, Craft M. Sexuality and mental handicap: a review. Br J Psychiatry. 1981;139:494–505. doi: 10.1192/bjp.139.6.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulehan JL, Block MR. The Medical Interview: Mastering Skills for Clinical Practice. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: FA Davis Co. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- Brody H. Transparency: informed consent in primary care. Hastings Cent Rep. 1989 19:5–9.In: Coulehan JL, Block MR. The Medical Interview: Mastering Skills for Clinical Practice. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: FA Davis Co. 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 589 A2d 637,640 (NJ Super Ct App Div 1991). [Google Scholar]