Abstract

Depressive disorders require long-term treatment with antidepressants, psychotherapy, or both. The goal of antidepressant therapy is complete remission of symptoms and return to normal daily functioning. Studies have shown that achieving remission and continuing antidepressant therapy long after the acute symptoms remit can protect against the relapse or recurrence of the psychiatric episode. Many patients, however, inadvertently or intentionally skip doses of their antidepressant, and even discontinue it, if their symptoms improve or if they experience side effects. Antidepressant discontinuation may increase the risk of relapse or precipitate certain distressing symptoms such as gastrointestinal complaints, dizziness, flu-like symptoms, equilibrium disturbances, and sleep disorders. Documented with all classes of antidepressants, these reactions may emerge within a couple of days, or even hours, after the abrupt discontinuation of an antidepressant with a short half-life. These distressing responses may be mistaken for a relapse or recurrence. It is important to recognize the potential for these sequelae and educate patients about the need to take all antidepressants at the doses prescribed, warning them of the symptoms that may occur if they skip doses or stop their medication too quickly. Antidepressants should be tapered slowly over a period of days, weeks, or even months, depending on the dose, duration of treatment, and pharmacologic properties of the agent, as well as the patient's individual response. This article reviews the risks and reactions associated with discontinuation of antidepressants. It offers guidelines for distinguishing relapse and recurrence from discontinuation responses as well as for prevention and management of the antidepressant discontinuation syndrome.

Major depression is a chronic condition with a naturally fluctuating course. Eventually, symptoms recur in half or more of patients.1,2 Numerous classes of antidepressant agents can successfully reduce depressive symptoms within several weeks, but this early improvement represents an acute response to treatment rather than a true remission.

The goal of antidepressant therapy is not just to reduce or eliminate the acute symptoms but also to achieve full remission—i.e., the complete relief of symptoms and the restoration of social and occupational functioning—and to maintain remission for as long as possible.2–4 Studies have shown that long-term use of antidepressants can protect against relapse (an early return or worsening of symptoms) and recurrence (later episodes occurring after remission) of depressive symptoms.4–6 Evidence also shows that recurrences are more common and develop earlier in patients who continue to experience residual symptoms than in patients who have achieved full remission.7,8 Discontinuation of antidepressant treatment too soon after an initial acute response may, therefore, increase the risk of relapse or recurrence.3,4

Antidepressant discontinuation at any stage of treatment can cause a variety of somatic and psychological reactions, especially if the withdrawal is abrupt. Although first identified 30 years ago with tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), these symptoms are not unique to TCAs, having now been documented with all classes of antidepressants, including monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), the serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and atypical agents (e.g., trazodone).4,9 Discontinuation symptoms are often associated with rapid withdrawal, but they have been reported with gradual dose tapering and even after 1 or 2 skipped doses.

This review examines current recommendations for long-term maintenance therapy with antidepressants as well as the timing and rate of discontinuation. It also outlines the symptoms associated with discontinuation of antidepressants, their possible mechanisms, and recommendations for preventing or managing the antidepressant discontinuation syndrome.

WHEN TO DISCONTINUE ANTIDEPRESSANT THERAPY

At some point in the treatment of mood disorders, the question of when to stop antidepressant treatment arises. Patients or physicians may opt to stop treatment after a symptomatic response is seen, after remission is achieved, after remission and functional improvements have been maintained for a reasonable amount of time, or when intolerable side effects occur or appear to outweigh the benefits of the drug.

Since true remission, rather than partial symptomatic response, is the therapeutic goal, it is essential to determine if remission has occurred before stopping treatment. The severity of depression and the response to antidepressant therapy are assessed with a number of tools. The Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) and the Clinical Global Impressions-Severity and -Improvement scales (CGI-S and CGI-I, respectively) are commonly used. Generally, a 50% reduction in the baseline HAM-D score and a CGI-I score of 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved) are considered to represent a good response to antidepressant treatment. However, these criteria may document symptomatic improvement but not necessarily remission. Minor symptoms may remain, increasing the risk of recurrence.3 More stringent criteria have been proposed that distinguish true remission from acute symptomatic response or a placebo response. These new remission criteria require a HAM-D score of ≤ 7 (considered a return to normal functioning) and a CGI-I score of 1. The Sheehan Disability Scale may be used to assess improvements in function, with a score of ≤ 1 (mild disability) indicating a complete return to normal functioning in family, social, and work situations.3 The Psychiatric Status Rating Scale may be used to evaluate recovery. Scores on this scale range from 1 (usual self, normal, no symptoms) to 6 (meets criteria for prominent symptoms or severe functional impairment). These and similar scales can be used in clinical practice to determine the return of normal functioning. The principle is that clinicians need to evaluate motivation and performance just as they would any other symptoms, such as sleep disturbance.

Pharmacologic therapy should be continued long enough to sustain remission and avoid relapses and recurrences. Relapse refers to a return of symptoms during the time in which the original depressive episode would have been expected to last (4–9 months). Recurrence refers to a return of depression at a time beyond the expected duration of the index episode (> 9 months after remission). This means that physicians and patients alike should not be too eager to discontinue medication prematurely. An interval of 6 months has been thought to be the usual duration of antidepressant therapy. New recommendations, however, suggest that treatment should continue for up to 9 months after symptoms have resolved (continuation phase) to prevent relapse and for longer to help prevent recurrence (maintenance phase).3 Some experts maintain that antidepressant treatment should continue for 3 to 5 years and possibly for life.1

Like all drugs, antidepressants may cause a variety of side effects that in some cases are severe enough to necessitate a quick discontinuation and a switch to another medication.1 Side effects, or the fear of side effects, may prompt patients to delay filling their antidepressant prescription or stop taking it as soon as their depressive symptoms begin to abate. Many patients take their antidepressant for 14 weeks or less.10 The effects of antidepressant treatment, however, may not be fully evident for 6 to 8 weeks, and long-term treatment is needed to ensure complete recovery and to prevent recurrence. Nevertheless, patients who are experiencing adverse reactions may be apt to discontinue their antidepressant prematurely, never achieving full remission and increasing their risk of relapse or of discontinuation reactions.

RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH DISCONTINUING ANTIDEPRESSANT THERAPY

The major risks after discontinuing an antidepressant include relapse or recurrence and discontinuation symptoms. These are quite distinct phenomena, with different causes and management implications.

Relapse or Recurrence

Long-term antidepressant treatment can prolong remission and protect against recurrence.1,4–6 Discontinuing antidepressant treatment is associated with a shorter time to relapse and an increased incidence of recurrence.1,10 One factor that appears to increase the risk of relapse is the persistence of residual symptoms.7,8 In one 10-year follow-up of patients with major depressive disorder, those with residual symptoms had a recurrence 5 times sooner than did those who had achieved asymptomatic status; the asymptomatic patients experienced fewer relapses and longer symptom-free intervals.2 Other factors predicting risk of relapse include a history of chronic depression11 and a history of multiple prior episodes.12 In a study of 141 patients diagnosed with major depressive disorder, those patients with 3 or more prior episodes had significantly shorter intervals from recovery to relapse than did patients having fewer than 3 prior depressive episodes.12

Age also is a predictive factor for recurrence: patients who had their first episode at an older age tend to relapse sooner than younger patients.1,12,13 Another factor that increases the likelihood of recurrence is the concurrent presence of substance abuse or comorbid anxiety disorder.11 A depressive relapse is more likely in the first weeks and months after recovery, with the risk declining with time.11,12 Continuing treatment is, therefore, especially crucial immediately after the acute resolution of symptoms.

Discontinuation Symptoms

Discontinuing antidepressant medications can precipitate a variety of somatic and psychological reactions in patients. These reactions, often termed antidepressant withdrawal or discontinuation syndrome, have been noted with all classes of antidepressant agents including TCAs, MAOIs, SRIs, SSRIs, and SNRIs. Since antidepressants are not addictive agents and do not directly evoke the brain reward systems, the term “discontinuation” is preferred over “withdrawal” when describing these symptoms. Although discontinuation symptoms are most often associated with the abrupt discontinuation of an antidepressant, they have been reported during gradual tapering and intermittent noncompliance as well.

Other risk factors associated with discontinuation reactions were reviewed by Lejoyeux and colleagues.14 These include the use of concurrent long-term medications such as antihypertensives, anticonvulsants, and antihistamines. Antidepressant treatment lasting 2 months or more and, in some reports, young age were also factors.14

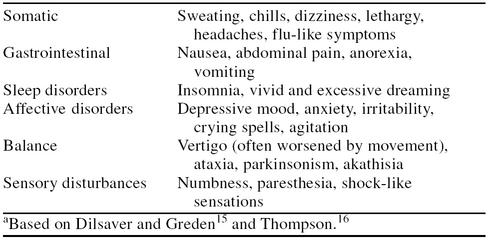

Table 1 lists some of the symptoms associated with the discontinuation of TCAs and SRIs.15,16 Although much of the evidence for the discontinuation syndrome comes from case reports, controlled clinical trials involving the abrupt switch from active antidepressant to placebo also have documented the occurrence of these reactions.17

Table 1.

Common Discontinuation Symptoms With Tricyclic Antidepressants and Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitorsa

It is especially important to recognize the symptoms of discontinuation and distinguish them from relapse and recurrence because a misdiagnosis may lead to unnecessary tests, useless treatments, and increased costs.18

Gastrointestinal complaints are common, with patients frequently suffering from nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and distention, and diarrhea.19,20 General somatic symptoms (e.g., sweating, lethargy, headaches, and a flu-like syndrome of chills, aches, and headaches), affective symptoms (e.g., anxiety, low mood), and sleep disorders (e.g., insomnia, vivid dreaming) are characteristic. Dizziness, balance problems, and sensory disturbances are also widely recognized with SSRI discontinuation.16,19,20 Mania or hypomania, movement disorders such as parkinsonism and akathisia, and cardiac arrhythmias also have been reported with antidepressant cessation but are not as common as the mood, somatic, and sleep problems.9,14,16,24

The symptoms of discontinuation, although usually mild and transient, can range widely in severity.15 Although the true incidence of discontinuation phenomena has not been established, these symptoms are believed to be common but not universal.22 Some patients may be genetically or temperamentally more susceptible to these responses, while other patients may be better able to tolerate them.23

Class-Specific Symptoms

Discontinuation symptoms differ among the antidepressant classes and even among the individual drugs within each class owing to the different mechanisms of action and the pharmacologic properties of the individual drugs.

TCAs.

TCA discontinuation reactions have been reported within hours of even 1 missed dose of imipramine.15 Typical responses to TCA discontinuation include abdominal pain, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, chills, fatigue, and weakness.14 The symptoms of TCA discontinuation, believed to be related in part to an adaptive hypersensitivity of muscarinic cholinergic receptors, are called cholinergic rebound or cholinergic overdrive. Long-term administration of TCAs blocks muscarinic cholinergic receptors in the human caudate,14,24 leading to a compensatory increase in the number of postsynaptic muscarinic receptors (up-regulation) and thus a supersensitivity to muscarinic agonists. Stopping the TCA unmasks this supersensitivity and may also disrupt the cholinergic-dopaminergic balance, contributing to the signs of parkinsonism and other balance disturbances that may occur with TCA discontinuation.14 Similar to SSRIs, most SRIs and TCAs can produce discontinuation symptoms.23

MAOIs.

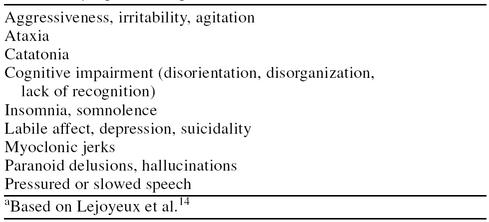

Discontinuation of MAOIs may cause severe and serious adverse events, including various types of cognitive impairment, aggression, catatonia, insomnia, irritability, paranoid delusions, depressed mood, and hallucinations (Table 2).14 These drugs down-regulate α2-adrenergic and dopaminergic receptors and possibly affect cholinergic receptors as well. MAOI withdrawal may stimulate the excessive release of both dopamine and norepinephrine via the removal of agonist activity on catecholamine receptors. Therefore, the symptoms can resemble those of amphetamine withdrawal.14,25,26 In 1 report, reducing the dose of tranylcypromine precipitated depressive episodes that were said to be worse than the depression for which the 5 patients were being treated; discontinuation also caused cognitive disturbances.27

Table 2.

Symptoms Reported After MAOI Discontinuationa

SRIs and SSRIs.

The SRIs and SSRIs block serotonin reuptake, increasing the amount of synaptic serotonin; this increase in available serotonin leads to a compensatory decrease in the number of some postsynaptic serotonin receptors (down-regulation).17 When the SSRI is discontinued abruptly, reuptake is reestablished (and possibly enhanced transiently), lowering the amount of available serotonin within the synapse. The resulting reduced concentration of available serotonin, plus the receptor down-regulation, causes clinical signs of serotonin deficiency. Since serotonin interacts with numerous other neurotransmitter systems, its deficiency has the potential to disrupt many other neuronal functions.

SSRI discontinuation symptoms are similar to those of the TCAs, with dizziness, gastrointestinal symptoms, and sleep disorders common. Anecdotal reports have included complaints of “electric shock–like” sensations, flashes, and “withdrawal buzz.”15,17,18,23–26,28–32 The type and severity of the symptoms correlate with the relative affinities of the agents for the serotonin reuptake sites and with secondary effects on other neurotransmitters; with SRIs that also affect cholinergic systems, the symptoms possibly correlate with cholinergic rebound.

Sudden discontinuation is a particular problem with agents that have a relatively short half-life, which include the SSRI paroxetine and the SNRI venlafaxine. With these types of drug, the symptoms can last up to 2 weeks.29 A randomized clinical trial reported that in the 5 to 8 days after discontinuation of an SSRI, symptoms were most common with paroxetine—the most potent SSRI and one with a short half-life—and least common with fluoxetine—an SSRI with a lower serotonin reuptake affinity and a longer half-life.31 Reactions to sertraline were mild and infrequent. However, this trial was designed to simulate intermittent noncompliance and did not attempt to document late-emerging effects that might occur with a drug with a long half-life, such as fluoxetine. There have been reports of symptoms starting 25 days after fluoxetine withdrawal with some persisting as long as 56 days.29 Late reactions to fluoxetine cessation may be reported less often because trials do not follow patients long enough after withdrawal to observe them. Further, the symptoms may be mild and patients may not attribute general symptoms such as flu-like complaints, dizziness, or sleep disturbances to a drug they had stopped taking weeks earlier.29

In addition to its effects on serotonin reuptake, paroxetine affects muscarinic receptors, and its withdrawal could contribute to symptoms of cholinergic rebound, a mechanism usually not attributed to other SSRIs.23 One case report of a patient discontinuing low-dose paroxetine (10 to 20 mg/day) noted symptoms that were very disabling initially and lasted longer than the 5 to 15 days mentioned in the prescribing information. The responses included agitation, anorexia, nausea and diarrhea, vertigo and dizziness, paresthesia, and a shaking chill.30 Sertraline, which like paroxetine is associated with a higher occurrence of discontinuation reactions, is the only SSRI that strongly blocks dopamine reuptake as well as serotonin-reuptake sites.23 Further, discontinuation symptoms with sertraline, although usually mild, may be related to its effect on both dopamine and serotonin reuptake.

SNRIs.

The therapeutic effectiveness of the SNRI venlafaxine is related to its dual inhibition of serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake. These actions stimulate a down-regulation of serotonergic and adrenergic receptors. Venlafaxine also weakly inhibits dopamine reuptake but has no significant affinity for muscarinic, histaminergic, or adrenergic receptors. Considering its relative lack of affinity for muscarinic cholinergic receptors, discontinuation symptoms associated with venlafaxine are probably not attributed to a cholinergic rebound phenomenon.33

A decrease in venlafaxine dose over 4 days to 2 weeks in a small sample of patients caused a flu-like syndrome with muscle pain, headaches, nausea, and dizziness.34 Eight patients in an open-label study reported discontinuation symptoms of rebound anxiety, vertigo, headache, nausea, tachycardia, tinnitus, and akathisia starting about 12 hours after discontinuing venlafaxine. For most patients, the dose was reduced gradually over 7 to 14 days, and the symptoms peaked in severity 4 days after the complete discontinuation before gradually dissipating.28

Distinguishing Discontinuation Syndrome From Relapse and Recurrence

The nature of the symptoms and the time course of their emergence can help in distinguishing discontinuation syndrome from relapse or recurrence. Discontinuation reactions may be physical as well as psychological, and they are usually not attributable to other causes. A distinctive symptom of discontinuation is dizziness, which is not characteristic of relapse and can often therefore be used in making the differentiation.35 Although discontinuation responses are generally mild, they can be severe, interfering with home, work, and daily activities such as driving. If symptoms of discontinuation emerge, they can be reversed by restarting the original antidepressant or a similar medication, which should then be slowly tapered to minimize the recurrence of the symptoms. Symptoms of relapse or remission are not so readily reversed.

The time course of the appearance of the symptoms also gives a clue as to their origin. Discontinuation-emergent reactions occur after abrupt discontinuation of the antidepressant or frequently missed doses, although they may occur as the dose is being reduced.32 The symptoms emerge within a couple of days—sometimes hours—of discontinuation and gradually remit over a few days to 2 weeks. In contrast, relapse or recurrence typically takes 2 or 3 weeks or longer after the medication is discontinued to emerge, and these events are heralded by worsening depression, insomnia, and psychomotor symptoms.18

Owing to their antidepressant and anxiolytic properties, newer antidepressant drugs such as the SSRIs and SNRIs also are being widely prescribed for anxiety disorders. The SSRIs have demonstrated efficacy for several anxiety disorders, including obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and social anxiety disorder.36 Venlafaxine XR (extended release) and paroxetine are the only antidepressants to receive U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for the treatment of GAD. The antidepressant and anxiolytic efficacy of these drugs can be attributed to their serotonin reuptake properties, which relate to their propensity for discontinuation effects. The relative contribution of the noradrenergic action of venlafaxine XR to its anxiolytic effect is unclear.37,38 It is not known whether discontinuing these medications among patients with anxiety disorders will result in the same somatic and psychological reactions as seen in patients with depression. Further research is needed.

ANTIDEPRESSANT DISCONTINUATION: RECOMMENDATIONS FOR DOSAGE TAPERING

Unfortunately, no drug-specific protocols for discontinuing antidepressants have been established. Prescribing information for each drug typically lacks recommendations for the rate and duration of tapering or criteria for antidepressant discontinuation. A review of the literature on these phenomena, however, shows that a slow taper is uniformly recommended.14,15,18 Inasmuch as antidepressant treatment generally continues for months to years, so should the taper be accorded adequate time to take effect. Several months may be required, depending on the dose, the pharmacologic profile of the drug, the duration of treatment, and the response of the patient.15

Because there has been little research on the ideal rates for antidepressant discontinuation, published recommendations for taper rates are often vague.39 Consequently, the magnitude and speed of the dose reduction are often left to clinical judgment. Some specific recommendations have been reported (Table 3).14,18,25,40 For example, MAOI dosages should not usually be reduced by more than 10% per week, and patients should be monitored carefully. TCAs should be reduced with great care over at least 2 to 3 months; if symptoms occur, the dose should be increased and the taper started again at a slower rate. With TCAs, it may be advisable to slow the taper even more near the end of the discontinuation phase.14

Table 3.

Gradual Taper Rates for Antidepressantsa

Since the therapeutic dosage levels of individual SSRIs vary so widely, their taper rate varies as well; however, gradual tapering also is recommended for this group of agents. A long half-life itself may provide a form of self-tapering but is not an absolute protection against discontinuation symptoms. For venlafaxine, even a taper regimen lasting 7 to 14 days induced symptoms of discontinuation in several patients in 1 of the clinical trials. The investigators therefore recommended that the drug be reduced over a minimum of 2 to 4 weeks (the prescribing information recommends a 2-week tapering for any patient treated for more than 1 week).28 Recently, the British National Formulary recommended a 4-week gradual dose reduction for any antidepressant prescribed for 2 months or more.19 The final step in the dosage taper may be lower than the minimum therapeutic or the initial treatment dose.18

PREVENTION AND MANAGEMENT OF DISCONTINUATION SYMPTOMS

Prevention is the best strategy for avoiding or minimizing discontinuation symptoms. Since some cases of discontinuation syndrome are due to missed doses or premature discontinuation by the patient, the first management goal is patient education. At the initiation of treatment, patients need to understand the chronic nature and fluctuating course of their symptoms and know that their symptoms will probably regress slowly over time. They should not consider symptom improvement as a cure, nor should they interpret the persistence of minor symptoms as a sign that treatment is ineffective. The goal of remission should be emphasized during patient encounters, and the need to continue treatment for months or even years should be explained thoroughly. As their symptoms remit and they begin to feel better, patients may wonder why they should continue taking their medication, especially if they are experiencing adverse reactions to the antidepressant. They may pressure their physicians into considering discontinuation of the drug. Since premature discontinuation can lead to both relapse and discontinuation reactions, the physician should ensure that patients understand that they must continue to take their medication, in the doses prescribed, for as long as necessary to achieve a true remission and avoid or delay recurrence. Antidepressant “vacations” should be discouraged, especially with antidepressants that have a short half-life, as even brief interruptions in therapy may precipitate an episode of discontinuation reactions.16 Patients suffering from discontinuation symptoms may attribute them to a direct side effect of the antidepressant and resist restarting the medication.

Physicians must consider the possibility of noncompliance when they encounter symptoms that might be related to antidepressant discontinuation. Asking patients if they have missed any doses may help avoid unnecessary tests and treatments as well as help initiate a discussion of the risks associated with stopping medication prematurely. Knowing the nature and duration of symptoms, plus obtaining information about noncompliance, can help differentiate discontinuation reactions from side effects and recurrences.41

Discontinuation symptoms occur even with a careful and gradual taper. They can be managed with several options. For mild symptoms, education and reassurance may be adequate.18 Symptoms can be reversed by restoring the antidepressant (or starting a similar antidepressant) and starting the taper again, reducing the dose in smaller increments during longer intervals. If restarting the antidepressant is not feasible for safety or tolerability reasons, other agents may be used to relieve the symptoms. Anticholinergic agents (e.g., benztropine, trihexyphenidyl) will improve the gastrointestinal symptoms, anxiety, sleep problems, and somatic reactions associated with the discontinuation of anticholinergic drugs such as the TCAs.41,42 Anxiety can be managed with a benzodiazepine and dizziness relieved with motion sickness agents (e.g., meclizine, dimenhydrinate). Propranolol can be used for akathisia, benzodiazepines for dyskinesia, and anticholinergic agents or antihistamines for dystonia, should these more serious reactions occur.42

CONCLUSION

Gastrointestinal complaints, dizziness, flu-like symptoms, sleep disorders, balance and sensory disorders, affective symptoms, and other reactions have been seen with the discontinuation of all classes of antidepressants. Antidepressant discontinuation symptoms typically emerge within a few days of drug discontinuation. Although sometimes very distressing, the symptoms are rarely serious and will dissipate within about 2 weeks. Reactions to MAOI withdrawal, however, may be more severe. Discontinuation symptoms can best be prevented or minimized by allowing neural adaptation to the loss of the drug to occur gradually, with careful and deliberate drug tapers over a few weeks to a few months. Specific discontinuation protocols for some of the new antidepressants such as venlafaxine may be found in the prescribing information published in the Physicians' Desk Reference.40 However, until data from systematic controlled studies are available, the case report literature offers some insight and suggestions, however vague, on the management and prevention of discontinuation symptoms.

More controlled studies on this common phenomenon are needed. For now, physicians must remind patients who suffer from depressive and anxiety disorders that the goal of antidepressant therapy is remission and that definite and immediate risks are associated with abruptly stopping antidepressant therapy, even for brief periods, or prematurely discontinuing treatment. Therefore, it is important for psychiatrists and primary care physicians to question patients about emerging discontinuation symptoms to ensure optimal management of treatment discontinuation and to prevent the emergence of additional discontinuation symptoms.

Drug names: benztropine (Cogentin and others), fluvoxamine (Luvox), fluoxetine (Prozac and others), meclizine (Antivert, Bonine, and others), paroxetine (Paxil), phenelzine (Nardil), propranolol (Inderal and others), sertraline (Zoloft), tranylcypromine (Parnate), trazodone (Desyrel and others), trihexyphenidyl (Artane and others), venlafaxine (Effexor).

Footnotes

Supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories, Philadelphia, Pa.

Dr. Shelton has received grant/research support from Eli Lilly, Glaxo, Janssen, Pfizer, Roehn-Polenc-Rorer, Sanofi, SmithKline Beecham, Wyeth-Ayerst, Zeneca, and Abbott; is a paid consultant for Pfizer and Janssen; and serves on the speakers bureau for Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Pfizer, SmithKline Beecham, Solvay, Wyeth-Ayerst, and Abbott.

REFERENCES

- Keller MB, Lavori PW, Mueller TI, et al. Time to recovery, chronicity, and levels of psychopathology in major depression: a 5-year prospective follow-up of 431 subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:809–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820100053010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd LL, Akiskal HS. Delineating the longitudinal structure of depressive illness: beyond clinical subtypes and duration thresholds. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2000;33:3–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-7967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballenger JC. Clinical guidelines for establishing remission in patients with depression and anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(suppl 22):29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entsuah AR, Rudolph RL, Hackett D, et al. Efficacy of venlafaxine and placebo during long-term treatment of depression: a pooled analysis of relapse rates. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;11:137–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Perel JM, et al. Three-year outcomes for maintenance therapies in recurrent depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:1093–1099. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810240013002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terra JL, Montgomery SA. Fluvoxamine prevents recurrence of depression: results of a long-term, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1998;13:55–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paykel ES, Ramana R, Cooper Z, et al. Residual symptoms after partial remission: an important outcome in depression. Psychol Med. 1995;25:1171–1180. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700033146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paykel ES. Remission and residual symptomatology in major depression. Psychopathology. 1998;31:5–14. doi: 10.1159/000029018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejoyeux M, Ades J. Antidepressant discontinuation: a review of the literature. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(suppl 7):11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller MB, Boland RJ. Implications of failing to achieve successful long-term maintenance treatment of recurrent unipolar major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:348–360. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00110-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIMH/NIH Consensus Development Conference Statement. Mood disorders: pharmacologic prevention of recurrences. Consensus Development Panel. Am J Psychiatry. 1985 142:469–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller MB, Lavori PW, Lewis CE, et al. Predictors of relapse in major depressive disorder. JAMA. 1983;250:3299–3304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint AJ, Rifat SL. Recurrence of first-episode geriatric depression after discontinuation of maintenance antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:943–945. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejoyeux M, Ades J, Mourad I, et al. Antidepressant withdrawal syndrome: recognition, prevention and management. CNS Drugs. 1996;5:278–292. [Google Scholar]

- Dilsaver SC, Greden JF. Antidepressant withdrawal phenomena. Biol Psychiatry. 1984;19:237–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson C. Discontinuation of antidepressant therapy: emerging complications and their relevance. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:541–548. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v59n1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajecka J, Tracy KA, Mitchell S. Discontinuation symptoms after treatment with serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a literature review. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:291–297. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n0702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum JF, Zajecka J. Clinical management of antidepressant discontinuation. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(suppl 7):37–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad P, Lejoyeux M, Young A. Antidepressant discontinuation reactions [editorial] BMJ. 1998;316:1105–1106. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7138.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie AK, Lannon RA, Ajari LJ. Withdrawal reaction after sertraline discontinuation. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:450–451. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.3.450b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann PM. Mania or hypomania after withdrawal from antidepressants. J Fam Pract. 1990;30:471–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A. Three cases of adverse symptoms occurring after the discontinuation of venlafaxine [letter] Psychiatr Ann. 1997;27:259. [Google Scholar]

- Schatzberg AF, Haddad P, Kaplan EM, et al. Possible biological mechanisms of the serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation syndrome. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(suppl 7):23–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilsaver SC. Antidepressant withdrawal syndromes: phenomenology and pathophysiology. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1989;79:113–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb08578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilsaver SC. Withdrawal phenomena associated with antidepressant and antipsychotic agents. Drug Saf. 1994;10:103–114. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199410020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilsaver SC. Heterocyclic antidepressant, monoamine oxidase inhibitor and neuroleptic withdrawal phenomena. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1990;14:137–161. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(90)90097-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halle MT, Dilsaver SC. Tranylcypromine withdrawal phenomena. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1993;18:49–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallal A, Chouinard G. Withdrawal and rebound symptoms associated with abrupt discontinuation of venlafaxine [letter] J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1998;18:343–344. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199808000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock BG. Discontinuation symptoms and SSRIs [letter with reply] J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:535–537. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v59n1007a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyke RE. Paroxetine withdrawal syndrome [letter] Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:149–150. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.1.149b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum JF, Fava M, Hoog SL, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:77–87. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatzberg AF. Introduction. Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome: an update on serotonin reuptake inhibitors. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(suppl 7):3–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens MJ, Morgan WN, Plott SJ, et al. Neurotransmitter receptor and transporter binding profile of anitdepressants and their metabolites. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:1305–1322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch SL, O'Sullivan RL, Jenike MA. Open treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder with venlafaxine: a series of ten cases [letter] J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;16:81–84. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199602000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum JF. Separating discontinuation symptoms from relapse [abstract] Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1999;9(suppl 5):S188. [Google Scholar]

- Boerner RJ, Möller HJ. The importance of new antidepressants in the treatment of anxiety/depressive disorders. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1999;32:119–126. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derivan A, Entsuah AR, Kikta D. Venlafaxine: measuring the onset of antidepressant action. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1995;31:439–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muth EA, Moyer JA, Haskins JT, et al. Biochemical, neurophysiological, and behavioral effects of Wy-45, 233 and other identified metabolites of the antidepressant venlafaxine. Drug Dev Res. 1991;23:191–199. [Google Scholar]

- Lazowick AL, Levin GM. Potential withdrawal syndrome associated with SSRI discontinuation. Ann Pharmacother. 1995;29:1284–1285. doi: 10.1177/106002809502901215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effexor XR. (venlafaxine hydrochloride extended release capsules). Physicians' Desk Reference. 54th ed. Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics. 2000 3237–3242. [Google Scholar]

- Garner EM, Kelly MW, Thompson DF. Tricyclic antidepressant withdrawal syndrome. Ann Pharmacother. 1993;27:1068–1072. doi: 10.1177/106002809302700912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe RM. Antidepressant withdrawal reactions. Am Fam Physician. 1997;56:455–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]