Abstract

A number of archaeal organisms generate Cys-tRNACys in a two-step pathway, first charging phosphoserine (Sep) onto tRNACys and subsequently converting it to Cys-tRNACys. We have determined, at 3.2-Å resolution, the structure of the Methanococcus maripaludis phosphoseryl-tRNA synthetase (SepRS), which catalyzes the first step of this pathway. The structure shows that SepRS is a class II, α4 synthetase whose quaternary structure arrangement of subunits closely resembles that of the heterotetrameric (αβ)2 phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase (PheRS). Homology modeling of a tRNA complex indicates that, in contrast to PheRS, a single monomer in the SepRS tetramer may recognize both the acceptor terminus and anticodon of a tRNA substrate. Using a complex with tungstate as a marker for the position of the phosphate moiety of Sep, we suggest that SepRS and PheRS bind their respective amino acid substrates in dissimilar orientations by using different residues.

Keywords: cysteine, methanogen, phosphoserine, archaea, aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase

Understanding the pathways through which simple systems evolve into more complex ones is a central concern in biology, one that has led to interest in elucidating the history of the apparatus for the translation of the genetic code into protein sequences. Aminoacyl tRNA synthetases (aaRSs), which charge tRNAs with the appropriate amino acids, provide a critical link in this apparatus. They are a diverse group of enzymes with exquisite specificity for both their amino acid and tRNA substrates (1). Many studies have therefore attempted to reconstruct the evolutionary histories of these enzymes (1–5). Apart from the direct route to aa-tRNA catalyzed by the aaRSs, an indirect pathway involving misacylation and subsequent tRNA-dependent amino acid modification operates in a number of cases, mainly for glutaminyl- and asparaginyl-tRNA formation (1, 6).

Although all aaRSs use a common two-step mechanism, first activating amino acids through the formation of aminoacyl–adenylate intermediates and then transferring the aminoacyl moieties onto the 3′ termini of tRNAs (1, 7–9), they can be divided into two evolutionarily independent classes (10, 11). The catalytic domains of class I synthetases contain Rossmann dinucleotide-binding folds (12, 13), whereas those of class II enzymes possess antiparallel β folds (11). The class II catalytic domains share three identifiable sequence motifs. Motif I consists of a helix, turn, and β strand and is typically part of an oligomeric interface, whereas motifs II and III form part of the active site. Additional motifs, sometimes associated with amino acid-binding pockets, permit the further classification of synthetases with respect to their amino acid substrates (2, 3, 5, 9, 14).

Several methanogenic archaeal organisms, although encoding proteins that contain cysteine, lack a gene encoding canonical cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase (CysRS) or have a dispensable form of this gene (3, 15, 16). This discrepancy has recently been resolved by the discovery of an indirect pathway for the formation of Cys-tRNACys in these organisms (16). A class II synthetase in these methanogens charges tRNA with Sep to form phosphoseryl-tRNACys (Sep-tRNACys), which is subsequently converted to Cys-tRNACys. This indirect pathway of Cys-tRNA formation is strikingly similar to the way eukaryotes and archaea synthesize selenocysteinyl-tRNA; both cases involve a Sep-tRNA intermediate (16, 17). One of the reasons why this indirect pathway to Cys-tRNACys was not identified earlier was that genes encoding SepRS were initially, and in some databases continue to be, misannotated as α subunits of the heterotetrameric (αβ)2 phenylalanyl tRNA synthetase (PheRS) because of the sequence similarity of these two synthetases.

Crystal structures of the PheRS from Thermus thermophilus have shown that PheRSs are unusually complex synthetases (18, 19). With the notable exception of the monomeric, mitochondrial Saccharomyces cerevisiae enzyme (20), they are heterotetramers. Their α subunits contain an N-terminal coiled-coil that is involved in tRNA recognition, followed by a class II catalytic domain. Their β subunits are much longer (785 aa long in T. thermophilus) and contain a catalytically inactive class II antiparallel β-fold as well as domains involved in tRNA recognition and editing (21–24). The sequence identity between the active and inactive catalytic domains of the α and β chains of PheRS is only 15% on average (25); nevertheless, the structures of these T. thermophilus domains are very similar, with an rmsd of 2.1 Å calculated >166 Cα pairs (18). There are two tRNA molecules per heterotetramer in the cocrystal structure, with each tRNA molecule contacting all four protein monomers. Thus the active site, anticodon-binding domain and N-terminal coiled coil that bind a tRNA molecule are each provided by separate polypeptide chains (19).

Although the primary sequences of SepRSs show that their closest relatives are PheRSs, the two families of enzymes must be significantly different. Both PheRSs and SepRSs recognize the different anticodons of their respective tRNAs (19, 26), and the details of these interactions must therefore differ. Furthermore, whereas in PheRS heterotetramers, the active sites are supplied by α subunits and the anticodon binding domains by β subunits, SepRSs are encoded by single genes and contain only one type of polypeptide. Perhaps the most striking difference between the two families of enzymes lies in the amino acids they recognize. Because phenylalanine and phosphoserine do not resemble each other in shape, hydrophobicity, or charge, the two families of synthetases must have evolved very different amino acid binding pockets. To address these issues, and to further understand the evolutionary relationship between PheRS and SepRS, we undertook structural and biochemical studies of the SepRS from M. maripaludis.

Results

Structure Determination and Domain Organization of SepRS.

We have determined the structure of the SepRS from M. maripaludis at 3.2 Å resolution. Initial phases were obtained through multiple isomorphous replacement by using tungstate and samarium derivatives. Preliminary model building into the resulting electron density map revealed the presence of a tetramer of SepRS within each asymmetric unit. Taking advantage of this redundancy, the phases were improved through multidomain noncrystallographic symmetry (NCS) averaging and solvent-flattening. Sharpening of the observed amplitudes by a B factor of 100 yielded a map that contained interpretable density throughout much of the molecule (Fig. 1). Subsequent rounds of building and refinement led to a model with a crystallographic R factor of 29.2% and Rfree of 30.6% (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

The structure of M. maripaludis SepRS. (A) The synthetase is a tetramer with pseudo 222 symmetry and is shown in surface representation, and the color of each monomer differs. The surface of one of the monomers is transparent, revealing a ribbon representation of its structure. (B) The catalytic domains of the SepRS tetramer shown in the same orientation as in A. Superimposed on this core are the two α and two β chains of the T. thermophilus PheRS (18). (C) A monomer of SepRS in the same orientation, colored by domain and motif. (D) Representative electron density for a helix in motif 1. To provide an unbiased view, the map was calculated by using phases derived without the use of the model; phases were produced by solvent-flattening and NCS-averaging heavy atom-derived phases. The amplitudes were sharpened by a B factor of 100 and the contour level set at 2σ to reveal side-chain density. (E) A structure-based sequence alignment of the catalytic domains of M. maripaludis SepRS, M. jannaschii SepRS, and the α and β-chains of the T. thermophilus PheRS. The secondary structure elements of the M. maripaludis SepRS are indicated and colored as in C.

Table 1.

Crystallographic statistics

| Measurement | Value |

|---|---|

| Space group | P212121 |

| Resolution, Å | 50.0–3.2 |

| Rmerge,* % | 5.3 (91) |

| I/σ† | 24.9 (1.1) |

| Completeness, % | 98.8 (94.4) |

| Unique reflections | 52,480 |

| Redundancy | 3.7 |

| Copies in AU | 4 |

| rmsd bond length, Å | 0.008 |

| rmsd bond angle, ° | 1.04 |

| Rcryst,‡ % | 29.2 |

| Rfree,‡ % | 30.6 |

| PDB ID code | 2ODR |

| Phasing power§ (acentric) | |

| Sodium tungstate | 1.6 (50–4.5 Å) |

| Samarium acetate | 1.1 (50–4.5 Å) |

| Overall figure of merit | |

| Heavy atom | 0.52 (50–4.5 Å) |

| Density modified | 0.73 (50–3.2 Å) |

*Rmerge is Σj Ij − 〈I〉, where Ij is the intensity of an individual reflection, and 〈I〉 is the mean intensity for multiply recorded reflections. The values in parentheses are for the high-resolution shell (3.31–3.2 Å).

†I/σ is the mean of intensity divided by the standard deviation.

‡Rcryst is Σ‖Fo − Fc‖/Σ Fo, where Fo is an observed amplitude and Fc a calculated amplitude; Rfree is the same statistic calculated over a subset of the data that has not been used for refinement.

§Phasing power is the rms isomorphous difference divided by the rms lack of closure.

N.D., not determined.

Each SepRS monomer can be divided into four domains and their connecting linker regions (Fig. 1). A small, N-terminal, helix–turn–helix domain is formed by residues 4 to 26. An extended linker containing residues 27 to 46 connect this domain with the catalytic domain (residues 47 to 99 and 179 to 343). As expected for a class II synthetase, the catalytic domain is composed of a six-stranded antiparallel β-sheet surrounded by helices and flanked by an additional β strand. This domain contains the three motifs characteristic of the class II synthetases: motif I is a strand and helix which typically forms part of a quaternary structure subunit interface (residues 47 to 70), motif II contains two antiparallel strands connected by a loop (residues 211 to 233) and is expected to be involved in ATP binding and tRNA recognition, whereas motif III is composed of a strand and helix that presumably also interacts with ATP (residues 315 to 330). Two short linkers connect the catalytic domain to an inserted domain that contains a helical bundle (residues 100 to 178, including the linker residues). This domain is poorly ordered, and its electron density is most interpretable in unsharpened maps truncated at 5 Å resolution. A short linker from residues 344–348 connects the catalytic domain to a C-terminal domain, which contains mixed α and β secondary structures. Although some of the sequence of this domain has been fitted to the electron density, in general, sequence register has not been established because of disorder. Much of this region, as well as the sequence corresponding to the inserted helical bundle domain, have therefore been either omitted or traced as polyalanine chains in the final model.

Quaternary Structure.

The structure of SepRS establishes that it is a highly interdigitated, homotetrameric enzyme consisting of a core and peripheral regions (Fig. 1). The core of this α4 assembly consists of catalytic domains along with residues 30 to 46 that link it to the N-terminal domain. The N-terminal, inserted, and C-terminal domains decorate the periphery of this core region (Fig. 1). The interactions between the core and peripheral domains bury surface areas that range from 360 to 900 Å2 when calculated per domain. Because some of the domains contain stretches of sequence that have currently been modeled as polyalanine or are incompletely traced, these values are a lower estimate. Nevertheless, their relatively small sizes suggest that the peripheral domains may be able to reorient and be positioned differently upon formation of the complex between tRNA and synthetase. Interestingly, all of the interactions between peripheral domains and the core region occur in trans, that is, the peripheral domain in a given monomer only forms interfaces with the core domain of a different monomer. This feature interlinks the monomers within the α4 particle. Overall, the assembly possesses approximate 222 point group symmetry, with the core region obeying the symmetry more strictly than the peripheral domains.

The structure of the core of the M. maripaludis SepRS α4 tetramer superimposes well on that of the core of the (αβ)2 heterotetramer of T. thermophilus PheRS (Fig. 1). This superposition simultaneously overlays the four catalytic domains of the SepRS tetramer with the two catalytic domains from the α chains and the two inactive catalytic-like domains from the β chains of PheRS. The rmsd between 525 corresponding Cα atoms in the two assemblies is 2.2 Å. In both cases the tetramer interface is composed of similar secondary structure elements (Fig. 1). This similarity in quaternary structure raises the possibility that the common ancestor of PheRS and SepRS may have shared a similar homotetrameric arrangement.

The peripheral domains of PheRS and SepRS share fewer similarities than their core regions. Although the α subunits of both enzymes contain an N-terminal helix–turn–helix, the helices in SepRS are less than half the length of those in PheRS. Furthermore, PheRS does not have a sequence insertion corresponding to the inserted domain of SepRS. Indeed, the only other synthetase of known structure that has a domain, albeit a smaller one, inserted in the same region of the catalytic domain as SepRS is Methanosarcina barkeri SerRS (27). Finally, database searches for similar structures by using the DALI server (28) have failed to find significant similarities between the structure of the C-terminal domain of SepRS and structures deposited in the protein data bank. This may suggest that this domain adopts a novel fold, or alternatively may be a consequence of the incomplete modeling of this domain of SepRS.

The Active Site.

Incubation of the crystals of SepRS in solutions containing phosphoserine severely degraded the quality of their diffraction. The active site of SepRS was therefore analyzed in three ways: we compared it with the active site of PheRS, examined the binding site of the phosphate mimic, WO4, and made active site mutations (Fig. 2; Table 2).

Fig. 2.

The active site of M. maripaludis SepRS compared with that of T. thermophilus PheRS (PDB ID code 1JJC) (29). (A) The catalytic domain of one monomer of SepRS (cyan) is shown superposed on a catalytic domain of PheRS (gray). This superposition is used in all images. Residues mutated in SepRS are shown in stick representation. Residue labels in all images are colored to indicate the severity of the mutant phenotype, and corresponding residue numbers in PheRS are shown in brackets. (B) Three T. thermophilus PheRS residues that interact with the AMP moiety are shown in gray. The corresponding residues in M. maripaludis SepRS are conserved (green). (C) Four T. thermophilus PheRS residues that form a binding pocket for the phenylalanyl side chain are shown in gray. The corresponding residues in M. maripaludis SepRS (green) are incompatible with the binding of phenylalanine. (D) Residues in M. maripaludis SepRS that may interact with the phosphate moiety of phosphoserine. Difference electron density, caused by incubating a crystal with sodium tungstate and contoured at 6σ, is shown as a mesh and superimposed on the structure both here and in F. (E and F) Side-by-side comparison of the interactions of T. thermophilus PheRS with phenylalanyl-adenylate and M. maripaludis SepRS with modeled phosphoseryl-adenylate. The side-chain conformations of M. maripaludis SepRS residues H186, T188, and R216 have been altered from the apo structure to accommodate the phosphoseryl moiety. The phosphoseryl phosphate group occupies a hydrophilic pocket, and its position overlaps the tungstate difference electron density.

Table 2.

Kinetic constants of phosphoserine activation by M. maripaludis SepRS mutants, measured by ATP–PPi exchange

| SepRS | Km (μM) | kcat (sec−1) | rel kcat/Km |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 72.43 ± 1.97 | 3.22 ± 0.03 | 1 |

| H186A | 737.92 ± 34.53 | 0.156 ± 0.004 | 0.0048 |

| S231A | N.D. | N.D. | 0.0003* |

| S233A | N.D. | N.D. | 0.0003* |

| K269A | 127.67 ± 28.60 | 0.50 ± 0.038 | 0.089 |

| S271A | 67.65 ± 17.44 | 2.20 ± 0.129 | 0.74 |

| K272A | 80.67 ± 20.03 | 0.79 ± 0.06 | 0.22 |

| Y273F | 343.46 ± 74.20 | 0.01 ± 0.001 | 0.007 |

| Y274F | 287.93 ± 81.53 | 1.95 ± 0.29 | 0.15 |

| N317A | N.D. | N.D. | <0.0001* |

*The catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) for this mutant was an approximation under sub-KM concentration of substrate.

Superposition of the structures of the active sites of M. maripaludis SepRS and T. thermophilus PheRS revealed the location of a number of conserved residues [Fig. 2B; and see supporting information (SI) Fig. 4]. In the structures of T. thermophilus PheRS bound to phenylalanyl-adenylate, or a nonhydrolyzable analog (29, 30), the side chains of some of these conserved residues contact the adenylate base (F216 and E218), adenylate phosphate (R204), and carbonyl (R204). Because these residues are conserved, it is plausible that they mediate contacts in SepRS similar to those observed in PheRS.

In contrast, the residues in the α chain of PheRS that interact with the phenylalanine side chain are not conserved. In particular, F258, F260, V261, and A314, which define a hydrophobic pocket for the phenyl side chain in T. thermophilus PheRS, correspond to residues S271, Y273, Y274, and N317, respectively, in SepRS. As a consequence of these differences in sequence, the volume of the corresponding pocket is substantially reduced in size and is hydrophilic in SepRS (Fig. 2C). This structural observation accords with previous biochemical results showing that SepRS does not activate or charge phenylalanine (16).

An additional set of differences permit SepRS to bind WO4 in a fashion that PheRS could not (Fig. 2D). Two of the SepRS residues that coordinate WO4 are S231 and S233 and they correspond to Q218 and E220 respectively in T. thermophilus PheRS. Steric clashes, and in the case of E220, electrostatic repulsion, preclude favorable interactions between these PheRS residues and WO4. Furthermore, another residue that coordinates WO4 in SepRS, N317, is an alanine in PheRS, a residue that cannot.

Nine point mutations made in the active site help identify regions that may be directly involved in contacting the phosphoseryl-adenylate substrate of SepRS (Fig. 2A; Table 2). Mutation of either K272 or S271 lead to minor effects on catalytic activity, making it unlikely that they directly contact substrate. In contrast, mutations of residues H186, S231, S233, or N317 to alanine or Y273 to phenylalanine reduce the kcat/Km by >100-fold. Of these five residues, only H186 is conserved in PheRS (T. thermophilus H178) where it is proximal to the α-amino moiety of phenylananine. These five residues considered together, form a plausible binding site for phosphoserine, consistent with the role that some of them may play in binding WO4.

Discussion

The results presented above have provided information on the arrangement of the active site of M. maripaludis SepRS, as well as its tertiary and quaternary structure. To further understand its mechanism, we have used these structural results as a basis for constructing homology models of the SepRS bound to tRNA and to the aminoacyl-adenylate.

Homology Modeling of Interactions Between Synthetase and tRNA.

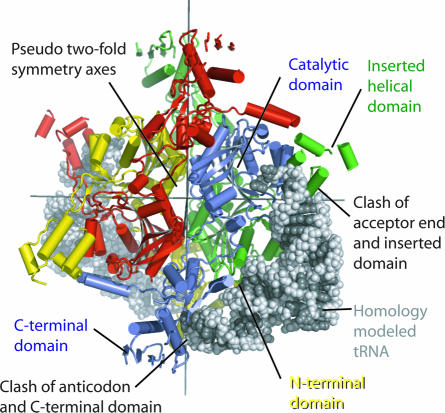

The tRNA from the structure of T. thermophilus PheRS complexed with tRNA can be homology modeled onto the structure of SepRS by using the superposition of the catalytic domain folds shown in Fig. 1. The phosphodiester backbone of the tRNA modeled in this fashion clashes with the SepRS main chain in two locations (Fig. 3). First, Gua1, Cyt74, and Cyt75 clash with the inserted domain. Second, the anticodon stem clashes with the C-terminal domain of the synthetase. One way to relieve these clashes would be through adjustment of the position of the modeled tRNA. Such adjustments are within the range of accuracy expected for a homology modeled complex. For example, tRNA does not clash with the inserted domain of SepRS if the homology modeling is based on the S. cerevisiae AspRS:tRNA structure (AspRS) (31) instead of the T. thermophilus PheRS:tRNA structure (although using the AspRS structure does increase the number of clashes between SepRS and the modeled anticodon stem). Alternatively, the orientations of the inserted and C-terminal domains within the SepRS tetramer might change upon binding tRNA. Such movements seem particularly likely for the inserted domains because they are very poorly ordered in our current structure, and thus appear not to be locked in place in the absence of tRNA.

Fig. 3.

tRNAPhe homology modeled onto the structure of SepRS by using the superposition of the catalytic domains of M. maripaludis SepRS and T. thermophilus PheRS (19) illustrated in Fig. 1B. The tRNAs are shown as white/gray surfaces; each polypeptide chain of SepRS is colored differently, and interactions between SepRS and one of the tRNAs are labeled.

The homology model is consistent with mutational data that were used to determine the identity elements of M. jannaschii tRNACys (26). In particular, both the model and the data support the proposal that SepRS contacts both the acceptor and anticodon ends of the tRNA. Furthermore, the mutational studies indicate that the changes G15A or C20U have only moderate effects on SepRS activity, consistent with the observation that they are far from the protein:tRNA interface in the homology model.

The N-terminal coiled-coil domain of SepRS does not interact with the homology modeled tRNA, but could do so with relatively small movements. Because this domain abuts the back of the active site, such a movement might link tRNA binding with changes at the active site. If the conformational changes within this domain upon tRNA binding are modest, it cannot interact with tRNACys in the extensive fashion that the much longer N-terminal coiled-coil of the α subunit of PheRS does with tRNAPhe. Alternately, the N-terminal domain of SepRS might have more substantial contacts with tRNA if the binding of nucleic acid triggers the turn in this domain to assume a helical conformation. Secondary structure prediction algorithms support such a possibility because they strongly score the turn as a helix.

Examination of the homology model suggests two further ways in which interactions of SepRS with tRNACys might differ from those of PheRS with tRNAPhe. First, the inserted domain of SepRS, which has no counterpart in PheRS, is poised to interact with tRNA. Second, in the model, the same monomer of SepRS that binds the acceptor end of a tRNA molecule in its active site, interacts with the tRNA anticodon through its C-terminal domain. This cis interaction is in marked contrast with PheRS, where α subunits provide the active sites, and β subunits the anticodon binding domains.

Modeling of Phosphoseryl-Adenylate in the Active Site of SepRS.

In modeling phosphoseryl-adenylate in the active site of SepRS, it is useful to consider the adenylate and aminoacyl moieties separately. The residues in T. thermophilus PheRS that bind the adenylate moiety of phenylalanyl-adenylate are conserved in SepRSs (Fig. 2B; supplementary Fig. 1). Thus importing the adenylate moiety by using a simple superposition of the active site of a PheRS cocrystal structure provides a plausible model for SepRS interactions with the adenylate.

The phosphoseryl moiety, by contrast, cannot be modeled by using conserved interactions. In T. thermophilus PheRS, a recognition loop containing F258, F260, and V261 is involved in binding the phenylalanine side chain. The corresponding loop in SepRS is more hydrophilic, and it had previously been proposed that residues from this loop might bind phosphoserine (25). In particular, it was suggested that M. jannaschii residues K281, S283, and K284 (K269, S271, and K272 respectively in M. maripaludis) might interact directly with the phosphate moiety. The functional consequences of mutation of the M. maripaludis SepRS (Fig. 2; Table 2) strongly argue against this suggestion. Furthermore, attempts to model the side chain in this region generate steric clashes because SepRS does not contain a pocket large enough to accommodate the phosphate at this location (Fig. 2; and see SI Fig. 4).

Tungstate, which has been previously used as a structural mimic of phosphate and thus is a marker for phosphate binding sites (32), provides an experimental constraint with which to model the position of the side chain of phosphoserine. Structural superposition of a catalytic domain of SepRS with a complex of S. cerevisiae AspRS bound to tRNA and ATP (33) indicates that the tungstate is a marker for the position of a phosphate moiety in phosphoserine rather than one of the phosphates of an ATP substrate. ATP in the active site of class II synthetases adopts a bent conformation (9, 33) and consequently, the distance between the tungsten and the α, β, and γ phosphorous atoms of the ATP from the superposed complex and the tungsten are 6, 9, and 11 Å, respectively. The superposition of the two synthetases aligns R324 in M. maripaludis SepRS with R531 in S. cerevisiae AspRS, a residue that interacts with the γ phosphate of ATP. As expected, this indicates that SepRS also binds ATP in a bent conformation.

A model of phosphoseryl-adenylate in the active site of SepRS, shown in Fig. 2F, is consistent with structural and mutational data. The orientation of the adenylate monophosphate moiety, as well as the protein interactions it makes, are very similar to those of the adenylate monophosphate moiety in a PheRS structure (29). In contrast, to avoid steric clashes and to position the serine linked phosphate at the location of the bound tungstate, we conclude that the orientation of the cognate aminoacyl group bound to SepRS differs from that bound to PheRS.

Conclusions

SepRS and PheRS differ in substantial ways. PheRSs, with the exception of the mitochondrial S. cerevisiae enzyme (20), are heterotetrameric, whereas SepRSs are homotetramers. Furthermore, similarities between the two families of synthetase do not appear to extend beyond their core catalytic domains. Perhaps most significantly, homology modeling of the SepRS substrate complex suggests that these homologous synthetases interact with both their tRNA and amino acid substrates in ways that differ. For example, the catalytic active site in PheRS is provided by the α subunit and tRNA anticodon recognition is mediated in trans by the β subunit, whereas in SepRS one monomer may provide both the anticodon recognition domain and the active site. The amino acid binding sites of the two families of synthetases also appear to be spatially distinct.

Despite these differences, the two families of synthetases share a number of similarities. The catalytic domains of SepRS and PheRS are structurally more similar than the catalytic and catalytic-like domains of the α and β chains of PheRS (28). The SepRS and PheRS families also share a distinct, superimposable quaternary structure. These similarities are all the more remarkable because the divergence of the two families may predate the last universal common ancestral state (25).

Materials and Methods

Wild-Type and Mutant SepRS Gene Constructs and Enzyme Purification.

Mutants were constructed by using a QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and a previously cloned M. maripaludis SepRS gene in a pET15b expression vector as a template (26). Mutations were confirmed by sequencing. Both wild-type and mutant His6-tagged M. maripaludis SepRSs were purified to apparent homogeneity as described (26). Purified protein was dialyzed against a buffer containing 20 mM Hepes-KOH pH 8.0, 40 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 10% glycerol.

Crystallization.

Before crystallization, the protein was dialyzed into a buffer containing 20 mM Na Hepes (pH 7.5), 5 mM DTT, and 5% glycerol. Crystals were grown by hanging-drop vapor diffusion, mixing equal volumes of protein (6–22 mg/ml) with well solution containing 4–6% PEG 35000, 5 mM DTT, 100 mM Na MES (pH 6.5), and 5% glycerol. They appeared overnight, and reached dimensions of up to 0.2 × 0.2 × 0.5 mm. The orthorhombic crystals were stabilized in 5–8% PEG 35000, 5 mM DTT, 50 mM Na MES (pH 6.5), and 5% glycerol and cryoprotected by increasing the final glycerol concentration to 30% in three steps of 5 min each before flash-freezing in liquid propane.

Structure Solution and Refinement.

Native crystals diffracted at best to 3.2 Å resolution and contained four monomers per asymmetric unit (Table 1). Initial phases were obtained by using crystals incubated with either 1 mM NaWO4 for 2 hours or with 1 mM Sm acetate for 30 minutes. These multiple isomorphous replacement phases were calculated by using the program SOLVE (34), and improved through the use of multidomain noncrystallographic symmetry averaging as implemented in the programs DM (35) and RESOLVE (36). Sharpening of the map by a B factor of 100 produced electron density that was interpretable over much of synthetase. Cycles of manual building that use the program COOT (37) and refinement with the program REFMAC (38) led to a model with a crystallographic R factor of 29.2% (Rfree of 30.6%) (Table 1). Figures were made by using Pymol (www.pymol.org).

Characterization of SepRS Mutants.

ATP-[32P]PPi exchange reaction assays were carried out at 37°C in 200 μl of buffer containing 50 mM Hepes-KOH (pH 8.0), 100 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 1 mM KF, 4 mM ATP, 2 mM 32PPi (5 cpm/pmol), 20–400 μM O-phosophoserine, and 0.25 μM SepRS. Forty-microliter aliquots of the reaction were removed periodically, mixed with activated charcoal (200 μl of 1% (wt/vol) Norit in 0.4 M sodium pyrophosphate solution with 15% (vol/vol) perchloric acid), and filtered on GF/C fiberglass filter disks (Whatman, Clifton, NJ). Filters were washed with 15 ml of H2O and 7 ml of ethanol, dried, and liquid scintillation-counted. Kinetic parameters (KM and kcat) were determined from the corresponding Eadie–Hofstee plots.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at National Synchrotron Light Source beamlines X25 and X29, at APS beamlines 19-ID and NECAT24-ID, and at Advanced Light Source beamlines 8.2.1 and 8.2.2; members of the T.A.S. laboratory for help with data collection and useful discussions; and the staff of the Center for Structural Biology core facility, especially Michael Strickler, at Yale. This work was funded by National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grants GM 22778 (to T.A.S.) and GM 22854 (to D.S.), Department of Energy Grant DE-FG02-98ER20311 (to D.S.), National Science Foundation Grant MCB-0645283, and a Feodor Lynen Postdoctoral Fellowship of the Alexander von Humboldt Stiftung (to M.J.H.).

Abbreviations:

- Sep

phosphoserine

- SepRS

phosphoseryl-tRNA synthetase

- PheRS

phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase

- CysRS

cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase

- AspRS

aspartyl-tRNA synthetase

- aaRSs

aminoacyl tRNA synthetases

- NCS

noncrystallographic symmetry.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Date deposition: Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 2ODR). This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0611504104/DC1.

References

- 1.Ibba M, Söll D. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:617–650. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolf YI, Aravind L, Grishin NV, Koonin EV. Genome Res. 1999;9:689–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woese CR, Olsen GJ, Ibba M, Söll D. Microb Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:202–236. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.1.202-236.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aravind L, Anantharaman V, Koonin EV. Proteins Struct Func Gen. 2002;48:1–14. doi: 10.1002/prot.10064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Donoghue P, Luthey-Schulten Z. Microb Mol Biol Rev. 2003;67:550–573. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.550-573.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tumbula DL, Becker HD, Chang WZ, Söll D. Nature. 2000;407:106–110. doi: 10.1038/35024120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoagland MB. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1955;16:288–289. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(55)90218-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zachau HG, Acs G, Lipmann F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1958;44:885–889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.44.9.885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arnez JG, Moras D. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:211–216. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eriani G, Delarue M, Poch O, Gangloff J, Moras D. Nature. 1990;347:203–206. doi: 10.1038/347203a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cusack S, Berthet-Colominas, Härtlein M, Nassar N, Leberman R. Nature. 1990;347:249–255. doi: 10.1038/347249a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Risler JL, Zelwer C, Brunie S. Nature. 1981;292:384–386. doi: 10.1038/292384a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhat TN, Blow DM, Brick P, Nyborg J. J Mol Biol. 1982;158:699–709. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90255-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delarue M, Moras D. BioEssays. 1993;15:675–687. doi: 10.1002/bies.950151007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bult CJ, White O, Olsen GJ, Zhou L, Fleischmann RD, Sutton GG, Blake J.A., FitzGerald LM, Clayton RA, Gocayne JD, et al. Science. 1996;273:1058–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sauerwald A, Zhu W, Major TA, Roy H, Palioura S, Jahn D, Whitman WB, Yates JR, III, Ibba M, Söll D. Science. 2005;307:1969–1972. doi: 10.1126/science.1108329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yuan J, Palioura S, Salazar JC, Su D, O'Donoghue P, Hohn MJ, Cardoso AM, Whitman WB, Söll D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:18923–18927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609703104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mosyak L, Reshetnikova L, Goldgur Y, Delarue M, Safro MG. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:537–547. doi: 10.1038/nsb0795-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldgur Y, Mosyak L, Reshetnikova L, Ankilova V, Lavrik O, Khodyreva S, Safro M. Structure (London) 1997;5:59–68. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00166-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanni A, Walter P, Boulanger Y, Ebel JP, Fasiolo F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8387–8391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roy H, Ling J, Irnov M, Ibba M. EMBO J. 2004;23:4639–4648. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kotik-Kogan O, Moor N, Tworowski D, Safro M. Structure (London) 2005;13:1799–1807. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roy H, Ibba M. Biochemistry. 2006;45:9156–9162. doi: 10.1021/bi060549w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sasaki HM, Sekine S-I, Sengoku T, Fukunaga R, Hattori M, Utsonomiya Y, Kuroishi C, Kuramitsu S, Shirouzu M, Yokoyama S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:14744–14749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603182103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Donoghue P, Sethi A, Woese CR, Luthey-Schulten Z. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:19003–19008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509617102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hohn MJ, Park H-S, O'Donoghue P, Schnitzbauer M, Söll D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:18095–18100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608762103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bilokapic S, Maier T, Ahel D, Gruic-Sovulj I, Söll D, Weygand-Durasevic I, Ban N. EMBO J. 2006;25:2498–2509. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holm L, Sander C. J Mol Biol. 1993;233:123–138. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fishman R, Ankilova V, Moor N, Safro M. Acta Crystallogr D. 2001;57:1534–1544. doi: 10.1107/s090744490101321x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moor N, Kotik-Kogan O, Tworowski D, Sukhanova M, Safro M. Biochemistry. 2006;45:10572–10583. doi: 10.1021/bi060491l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moulinier L, Eiler S, Eriani G, Gangloff J, Thierry JC, Gabriel K, McClain WH, Moras D. EMBO J. 2001;20:5290–5301. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.18.5290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.le Maire A, Schiltz M, Stura EA, Pinon-Lataillade G, Couprie J, Moutiez M, Gondry M, Angulo JF, Zinn-Justin S. J Mol Biol. 2006;364:764–776. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cavarelli J, Eriani G, Rees B, Ruff M, Boeglin M, Mitschler A, Martin F, Gangloff J, Thierry JC, Moras D. EMBO J. 1994;13:327–337. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06265.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Terwilliger TC, Berendzen J. Acta Crystallogr D. 1999;55:849–861. doi: 10.1107/S0907444999000839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cowtan K. Joint CCP4 ESF-EACBM Newslett Protein Crystallogr. 1994;31:34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Terwilliger TC. Acta Crystallogr D. 2000;56:965–972. doi: 10.1107/S0907444900005072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Acta Crystallogr D. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Acta Crystallogr D. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.