Abstract

Accumulating evidence suggests that dopamine D3 receptor (D3R) stimulation is inhibitory to spontaneous and psychostimulant-induced locomotion through opposition of concurrent D1R and D2R-mediated signaling. To evaluate this model, we used homozygous D3R mutant mice and wild-type controls to investigate the role of the D3R in locomotor activity and stereotypy stimulated by acute amphetamine (AMPH) (0.2, 2.5, 5.0, 10.0 mg/kg). At the lowest dose tested (0.2 mg/kg), neither D3R mutant mice nor wild-type mice exhibited measurable change in locomotor activity or stereotypy relative to their respective saline-treated controls. D3R mutant mice exhibited a significantly greater increase in locomotor activity, but not stereotypy, relative to wild-type mice in response to treatment with AMPH 2.5 mg/kg. AMPH-induced locomotor activity and stereotypy were similar in both wild-type and D3R mutant mice at both the 5.0 and 10 mg/kg AMPH doses. These findings provide further support for an inhibitory role for the D3R in AMPH-induced locomotor activity, and demonstrate a more limited role for the D3R in modulating AMPH-induced stereotypy.

Keywords: dopamine D3 receptor, mutant mice, amphetamine, dose–response, locomotor activity, stereotypy

INTRODUCTION

The same mesolimbic and nigrostriatal dopamine (DA) pathways modulating reward processes in the mammalian brain also play a role in mediating motor behaviors including locomotion and stereotyped behaviors. Dopaminergic signaling in these pathways is mediated by G protein-coupled receptors grouped into two subfamilies: D1-like (D1 and D5) and D2-like (D2, D3, and D4) (reviewed in Missale et al., 1998). Accumulating evidence from pharmacological studies suggest that D3R stimulation is inhibitory to spontaneous and psychostimulant-induced locomotion, in opposition to concurrent D1R- and D2R-mediated signaling (Carr et al., 2002; De Boer et al., 1997; Ekman et al., 1998; Kling-Petersen et al., 1995; Ouagazzal and Creese, 2000; Pritchard et al., 2003; Waters et al., 1993; Xu et al., 1997; Zhang et al., 2004). A clear understanding of D3R behavioral functions has been limited, however, by the limited selectivity of D3R agonists and antagonists. An alternative approach to understanding the behavioral function of the D3R has been the use of D3R knockout mice (reviewed in Holmes et al., 2004). Three lines of mutant mice lacking the D3R have been independently generated (Accili et al., 1996; Jung et al., 1999; Xu et al., 1997). D3R mutant mice exhibit normal D1R and D2R binding profiles and brain distributions (Accili et al., 1996; Xu et al., 1997; Wong et al., 2003), suggesting that effects on DA signaling in adult mice following selective mutation of the D3R are mediated primarily through loss of D3R expression.

At the behavioral level, the originally described increased spontaneous locomotor activity exhibited by D3R mutant mice (Accili et al., 1996; Xu et al., 1997) has been replicated by some studies (Betancur et al., 2001; Boulay et al., 1999; Vallone et al., 2002) but not others (Joseph et al., 2002; Jung et al., 1999; McNamara et al., 2002). A significant increase in novelty-induced stereotypy has also been observed in D3R mutant mice relative to wild-type controls (Joseph et al., 2002). With regard to psychostimulant-induced locomotor activity, acute cocaine-induced locomotor activity was significantly greater in D3R mutant mice relative to wild-type mice at the lowest dose (5 mg/kg) tested; however, this effect was not observed at higher doses (10–40 mg/kg) (Xu et al., 1997). Subsequent studies have similarly observed that higher doses of acute cocaine (20–30 mg/kg) produce comparable elevations in locomotor activity in D3R mutant and wild-type mice (Betancur et al., 2001; Carta et al., 2000). Repeated treatment with high dose cocaine (25 mg/kg twice daily) also increased stereotypy and reduced locomotor activity to a greater degree in D3R mutant mice than in wild-type mice (Carta et al., 2000), while a second study observed similar effects on stereotypy and locomotor activity in D3R mutant mice and wild-type animals in response to repeated cocaine treatment (20 mg/kg/day) (Betancur et al., 2001). Cocaine and amphetamine (AMPH) have overlapping, but distinct, mechanisms of action (reviewed in Riddle et al., 2005), and to date there have been no published studies evaluating AMPH-induced locomotor activity and stereotypy in wild-type and D3R mutant mice. Therefore, in the present study we examined the effects of acute AMPH (0.2, 2.5, 5.0, 10.0 mg/kg) treatment on locomotor activity and stereotypy in homozygous D3R mutant mice and wild-type mice. We demonstrate that AMPH-induced locomotor activity is significantly elevated in D3R mutant mice relative to wild-type mice in a dose-dependent manner, while stereotypy ratings were similar at all AMPH doses in D3R mutant mice and wild-type animals. These findings provide further evidence that the D3R plays an inhibitory role in psychostimulant-induced locomotor activity, and suggest that the D3R plays a more limited role in the modulation of acute AMPH-induced stereotypy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Details regarding the generation and validation of the homozygous D3R mutant mice used in this study have been described previously (Xu et al., 1997). The genetic backgrounds of both mutant and wild-type mice are C57BL/6 × 129Sv, and mice have subsequently been backcrossed for three generations with inbred C57BL/6 mice to reduce the number of 129Sv-linked genes to 12.5% (Silver, 1995). Adult (8–12 weeks) male mice used in the present study were genotyped by PCR using DNA extracted from tail clips, as previously described (Pritchard et al., 2003). Experimental animals were housed with same sex siblings with 4–5 animals per cage in SPF Murine Facilities maintained on a 12:12 light:dark cycle. Behavioral testing was performed during the light phase of the cycle (between 0900 and 1700) and food and water were available ad libitum. All experiments were carried out in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Drugs

d-Amphetamine sulfate (AMPH) (Research Biochemicals, Int., Natick, MA) was dissolved in 0.9% NaCl. AMPH concentrations are described as free base. All injections were administered subcutaneously in a volume of 1.0 ml/kg, and control injections consisted of an equivalent volume of the drug vehicle (0.9% NaCl).

Behavioral apparatus

Behavioral testing was performed in 30 automated activity chambers, each consisting of a lighted, ventilated, sound-attenuated cabinet housing a 40 × 40 × 38 cm3 Plexiglas enclosure. Horizontal locomotor activity was monitored with a 16 × 16 photo beam array (San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA) located 1.25 cm above the floor of the enclosure, as previously described (Pritchard et al., 2003). An air evacuation fan in each enclosure provided constant air circulation and background noise. Each chamber had an overhead-mounted video camera connected to a VCR to record behavior.

Locomotor activity

Mice were transported from the adjacent vivarium to the activity chamber room 30 min prior to placement into activity chambers. All mice were first acclimated to the activity chamber for 1 h prior to injections, and locomotor activity was recorded for 3 h following drug administration. Locomotor activity is expressed as crossovers, defined as entry into any of the active zones of the chamber, as previously described (Pritchard et al., 2003). Mice were randomly distributed to each treatment group, with saline- and AMPH-treated mice run in parallel.

Stereotypy

Stereotyped behaviors were scored from videotape recordings for 60-s periods starting 5 min after AMPH injection, and continuing every 5 min for 1 h. Data were collected and presented as the percentage of the 60-s observation period during which the mouse displayed stereotyped behaviors, as previously described (Segal and Kuczenski, 1987). Stereotyped behaviors were defined as focused sniffing, repetitive head bobbing, rearing, and oral behaviors (gnawing, flank grooming/licking) in the absence of locomotor activity. Raters were blind to mouse genotype and treatment condition at the time of scoring.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (Version 9.1, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) PROC MIXED procedure. Crossover data was analyzed with a three-way ANOVA, with Genotype (wild-type, D3R mutant) and Drug dose (0, 0.2, 2.5, 5.0, 10 mg/kg) as main factors, and Time interval (20 × 9 min intervals over 3 h) as the repeated measure. Stereotypy data was analyzed with a three-way ANOVA, with Genotype (wild-type, D3R mutant) and Drug dose (0, 0.2, 2.5, 5.0, 10 mg/kg) as main factors, and Time interval (12 × 5 min bins over 1 h) as the repeated measure. Fisher's LSD multiple comparisons tests were used with α = 0.05. Activity and stereotypy measures were obtained from the same mice.

RESULTS

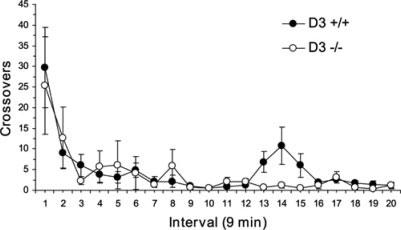

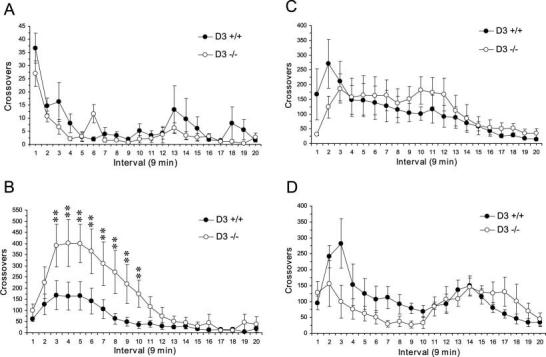

The effect of saline injection on locomotor activity of wild-type and D3R mutant mice is presented in Figure 1, and individual AMPH dose comparisons are presented in Figures 2 and 3A. A three-way ANOVA with repeated measures found significant main effects of Dose, F(4,800) = 123.4, P < 0.0001, Time interval, F(19,893) 6.77, P < 0.0001, but not Genotype F(1,47) = 1.86, P = 0.186, and a significant Genotype × Dose Interaction, F(4,47) = 3.08, P = 0.025. Furthermore, there was a significant Genotype × Dose × Time Interaction, F(76,893) = 1.57, P = 0.002. Within wild-type mice, locomotor activity stimulated by the 2.5 (P ≤ 0.01), 5.0 (P ≤ 0.01), and 10.0 mg/kg (P ≤ 0.01) AMPH doses were significantly greater than locomotion following saline treatment. Locomotor activity following the 0.2 mg/kg AMPH dose did not differ significantly from saline treatment (P > 0.05). Similarly, within D3R mutant mice, locomotor activity stimulated by the 2.5 (P ≤ 0.01), 5.0 (P ≤ 0.01), and 10.0 mg/kg (P ≤ 0.01) AMPH doses were significantly greater than locomotion following saline treatment. Locomotor activity following the 0.2 mg/kg AMPH dose did not differ from saline treatment. Comparisons between wild-type and D3R mutant mice found significant differences at the 2.5 mg/kg AMPH dose (P ≤ 0.01) (Fig. 2B). A separate analysis of the first 10 intervals following the 10 mg/kg dose found a significant main effect of Time, F(9,90) = 4.72, P ≤ 0.0001, whereas the main effect of Genotype, F(1,10) = 4.70, P = 0.055, and the Genotype × Time Interaction, F(9,90) = 1.12, P = 0.32, did not reach significance. Similarly, a separate analysis of the last 10 intervals following the 10 mg/kg dose found a significant main effect of Time, F(9,90) = 3.73, P = 0.0005, whereas the main effect of Genotype, F(1,10) = 0.82, P = 0.386, and the Genotype × Time Interaction, F(9,90)= 0.77, P = 0.65 did not reach significance. Analysis of the last five intervals following the 10 mg/kg dose found a significant main effect of Time, F(4,40) = 7.03, P = 0.0002, whereas the main effect of Genotype, F(1,10)= 0.257, P = 0.257, and the Genotype × Time Interaction, F(4,40) = 0.364, P = 0.36, did not reach significance.

Fig. 1.

Effect of saline injection on locomotor activity in wild-type (D3 +/+; n = 6) and D3R mutant (D3 −/−; n = 6) mice. Note that wild-type and D3R mutant mice exhibit comparable levels of locomotor activity over the 3 h observation period. Data are expressed as group mean crossover ±SEM.

Fig. 2.

Effect of acute AMPH (0.2, 2.5, 5.0, 10.0 mg/kg) on locomotor activity in wild-type (D3 +/+; n = 5–6/group) and D3R mutant (D3 −/−; n = 5–6/group) mice (A–D, respectively). Note that D3R mutant mice exhibit significantly greater locomotor activity in response to AMPH 2.5 mg/kg relative to wild-type mice (B), and wild-type and D3R mutant mice exhibit similar alterations in locomotor activity in response to high doses of AMPH (5.0 and 10.0 mg/kg) (C, D). Data are expressed as group mean crossover ± SEM. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01 vs. wild-type mice.

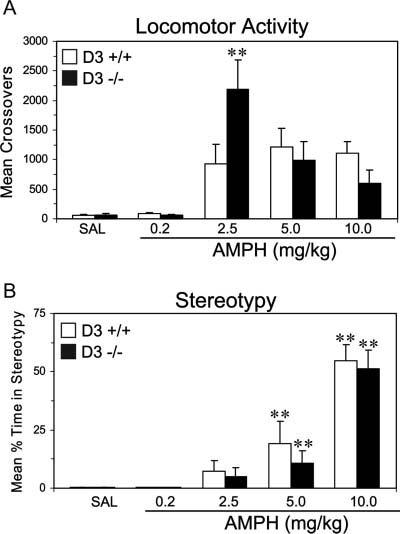

Fig. 3.

Effect of acute AMPH (0.2, 2.5, 5.0, 10.0 mg/kg) on (A) locomotor activity and (B) stereotypies in wild-type (D3 +/+) and D3R mutant (D3 −/−) mice during the first 60 min following injections. Note: (1) AMPH dose-dependently increases locomotor activity and stereotypies in both wild-type and D3R mutant mice relative to their respective saline controls; (2) acute AMPH (2.5 mg/kg) induces significantly greater locomotor activity in D3R mutant mice relative to wild-type mice despite the absence of differences in stereotypies. **P ≤ 0.01 vs. wild-type mice in (A), **P ≤ 0.01 vs. saline controls in (B).

Analysis of stereotypy scores following acute AMPH treatment are presented in Figure 3B. For this analysis, data could not be collected for three mice because of the failure of the video recording equipment. A three-way ANOVA with repeated measures found significant main effects of Time, F(11,484) = 3.07, P ≤ 0.0005, and Dose, F(4,44) = 34.6, P = 0.0001, and a significant Time × Dose Interaction, F(44,484) = 1.85, P = 0.001. However, the main effect Genotype was not significant, F(1,44) = 0.05, P = 0.83, and the Genotype × Dose Interaction, F(4,44) = 0.25, P = 0.907, and Genotype × Dose × Time Interaction, F(44,484) = 1.29, P = 0.107, were not significant. Stereotypy stimulated by the 5.0 mg/kg (P ≤ 0.01) and 10.0 mg/kg (P ≤ 0.01) AMPH doses were significantly greater than stereotypy following saline treatment for both wild-type and mutant mice. Stereotypy stimulated by the 0.2 and 2.5 mg/kg AMPH doses did not differ significantly from saline treatment for either wild-type or mutant mice (P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, locomotor activity and stereo-typy were significantly elevated in wild-type and D3R mutant mice following acute AMPH treatment in a dose-dependent manner relative to their respective saline-treated controls. Moreover, AMPH-induced locomotor activity is significantly greater in D3R mutant mice than wild-type mice at the 2.5 mg/kg dose, while elevations in stereotypy are comparable in the two strains following this treatment. Stereotypy increased in both wild-type and D3R mutant mice with elevating AMPH dose, resulting in a concomitant decrease in locomotor activity in both wild-type and D3R mutant mice. Stereotypy scores did not differ significantly between wild-type and D3R mutant mice at any of the AMPH doses evaluated.

The behavioral response of D3R knockout mice to AMPH are in general agreement with those reported by other investigators in response to cocaine treatment. Specifically, a low cocaine dose (5 mg/kg) produced significantly greater locomotor activity in D3R mutant mice relative to wild-type mice, whereas higher doses (10–40 mg/kg) produced comparable alterations in both locomotor activity and stereotypy in D3R and wild-type mice (Betancur et al., 2001; Carta et al., 2000; Xu et al., 1997). Collectively, these findings add to a growing body of evidence that support the model that D3R plays an inhibitory role in psychostimulant-induced locomotor activity, but not stereotypy, in a dose-dependent manner.

The finding that D3R knockout mice display more prominent perturbations in the regulation of locomotion than stereotypy in response to stimulant drugs is of interest in light of the relative distribution of D3R in the dorsal and ventral striatum. Specifically, D3R is highly expressed in the ventral striatum [nucleus accumbens (shell) and islands of Calleja], while it is expressed at low/absent levels of detection in the rat caudate-putamen (Diaz et al., 2000). Lesions of the substantia nigra (Creese and Iversen, 1975; Roberts et al., 1975) and mesolimbic DA systems (Costall and Naylor, 1974; Pijnenburg et al., 1975) attenuate the locomotor stimulant actions of AMPH, while the stereotypy producing effects are blocked by lesions of the nigrostriatal DA pathway (Creese and Iversen, 1972, 1975). Therefore, the D3R may play a more central role in mediating DA signaling in the mesoaccumbens DA pathway than the nigrostriatal DA pathway with respect to acute psychostimulant treatment. Within the ventral striatum, D3R are coexpressed with D1R in the majority of neurons (Ridray et al., 1998; Surmeier et al., 1996), and the D3R and D1R interact in an antagonistic manner in the regulation of neuronal c-fos expression in response to psychostimulant treatment (Ridray et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 2004), and in the regulation of locomotor activity (Mori et al., 1997; Xu et al., 1997). Therefore, reductions in D3R-mediated opposition to concomitant D1R signaling following AMPH-induced elevations in DA release within the nucleus accumbens may contribute to the elevated locomotor response observed in D3R mutant mice.

A possible contribution of presynaptic D3 receptors to the observed behavioral effect is less clear, as the degree to which the D3R functions as an autoreceptor vs. postsynaptic function has not been clearly determined. Two studies using different D3R mutant mouse strains demonstrated that autoreceptor regulation of DA synthesis is intact in D3R knockout mice, while regulation of DA release is minimally impaired in D3R knockouts (Joseph et al., 2002; Koeltzow et al., 1998). Extracellular DA levels were elevated in the ventral striatum (Koeltzow et al., 1998) and caudate-putamen (Joseph et al., 2002) of D3R mutant mice relative to wild-type controls, suggesting some role for the D3R in the regulation of extracellular DA levels. In contrast, D2R knockout mice display complete loss of DA autoreceptor function (Mercuri et al., 1997). In another study, extracellular DA levels, and potassium- as well as cocaine-induced elevations in DA, were similar in the ventral striatum of wild-type and D3R mutant mice, while the D3R agonist (+)-PD 128907 selectively reduced extracellular DA concentrations in wild-type, but not D3R mutant, mice (Zapata et al., 2001). In summary, evidence from several different laboratories suggests that D3R contributes to regulation of DA release, while D2 autoreceptors regulate DA synthesis. Further study is needed to identify whether loss of autoreceptor modulation of DA release contributes to elevated AMPH stimulated locomotion in D3 knockout mice.

Accumulating evidence suggests that the D3R may play an important role in both the pathophysiology, and treatment-emergent side effects, of Parkinson's disease (reviewed in Joyce, 2001). Specifically, dyskinesias, characterized by loss of motor control manifesting as tics, spasms, or myoclonus, are a common side effect of chronic levo (l)-dopa administration used in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Dyskinesias are thought to result from behavioral sensitization to l-dopa-induced elevations in DA transmission (Bezard et al., 2001). Interestingly, MPTP-treated monkeys, an animal model of Parkinson's disease, exhibit a significant loss of D3R binding in the caudate nucleus (Bezard et al., 2003), and l-dopa-induced dyskinesia in MPTP-treated monkeys is significantly attenuated by the D3R-selective partial agonist BP897, and antagonists nafadotride and ST 198 (Guillin et al., 2003). The present findings imply that the absence of D3R neither enhances nor protects against stereotypic behaviors resulting from elevated DA neurotransmission, suggesting that although l-dopa-induced dyskinesias and AMPH-induced stereotypic behaviors superficially share some common behavioral features, they would appear to recruit different dopaminergic pathways.

The rodent behavioral response to low dose AMPH treatment is characterized by elevated locomotor activity, while the behavioral response to higher AMPH doses includes focused stereotyped movements, which compete with locomotion and therefore inhibit locomotor activity. Following completion of the episode of elevated stereotypy, animals exhibit a poststereotypy period of elevated locomotion (Segal and Kuczenski, 1994). While a quantitative analysis of the behavioral response to AMPH 10 mg/kg did not identify differences in locomotion or stereotyped behaviors between wild-type and D3R knockout mice, comparison of the relative shapes of the curves for the two genotypes suggests a trend toward decreased locomotion during the time period of elevated stereotypy, followed by an exaggerated locomotor response period of poststereotypy hyper-locomotion (Fig. 2, Panel D). To further examine the possibility of opposing effects on locomotion during different periods following AMPH injection, a separate analysis was done during the time periods of stereotypy (first 10 intervals) and poststereotypy hyperlocomotion (last 5 intervals). These analyses also failed to detect a quantitative difference between D3R knockout and wild-type mice: neither main effects of Genotype, nor Genotype × Time Interactions, were significant. Thus, in summary, while clear evidence for a quantitative difference in stereotyped behavior between D3R knockout and wild-type mice was not detected in the analysis of behavioral response to higher dose AMPH, the relative shapes of the locomotor response curves for wild-type vs. D3R knockout mice suggest a modest effect of D3R on stereotyped behaviors that is below the level of reliable detection.

In conclusion, our findings support the model that the D3R plays an inhibitory role in AMPH-induced locomotor activity, and suggests that the D3R plays a limited role in the regulation of AMPH-induced stereotypy. These findings add to a growing body of evidence that support the model that D3R plays an inhibitory role in psychostimulant-induced locomotor activity.

Footnotes

Contract grant sponsor: Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Research Service; Contract grant sponsor: National Institute of Drug Abuse; Grant numbers: DA016778-01, DA11284, DA14644, DA17323.

REFERENCES

- Accili D, Fishburn CS, Drago J, Steiner H, Lachowicz JE, Park BH, Gauda EB, Lee EJ, Cool MH, Sibley DR, Gerfen CR, Westphal H, Fuchs S. A targeted mutation of the D3 dopamine receptor gene is associated with hyperactivity in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1945–1499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancur C, Lepee-Lorgeoux I, Cazillis M, Accili D, Fuchs S, Rostene W. Neurotensin gene expression and behavioral responses following administration of psychostimulants and anti-psychotic drugs in dopamine D(3) receptor deficient mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;24:170–182. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00179-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezard E, Brotchie J, Gross C. Pathophysiology of levodopa-induced dyskinesia: Potential for new therapies. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:577–588. doi: 10.1038/35086062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezard E, Ferry S, Mach U, Stark H, Leriche L, Boraud T, Gross C, Sokoloff P. Attenuation of levodopa-induced dyskinesia by normalizing dopamine D3 receptor function. Nat Med. 2003;9:762–767. doi: 10.1038/nm875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulay D, Depoortere R, Perrault G, Borrelli E, Sanger DJ. Dopamine D2 receptor knock-out mice are insensitive to the hypolocomotor and hypothermic effects of dopamine D2/D3 receptor agonists. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:1389–1396. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr KD, Yamamoto N, Omura M, Cabeza de Vaca S, Krahne L. Effects of the D(3) dopamine receptor antagonist, U99194A, on brain stimulation and d-amphetamine reward, motor activity, and c-fos expression in ad libitum fed and food-restricted rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;163:76–84. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carta AR, Gerfen CR, Steiner H. Cocaine effects on gene regulation in the striatum and behavior: Increased sensitivity in D3 dopamine receptor-deficient mice. Neuroreport. 2000;11:2395–2399. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200008030-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costall B, Naylor RJ. Extrapyramidal and mesolimbic involvement with the stereotypic activity of d- and l-amphetamine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1974;25:121–129. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(74)90039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creese I, Iversen SD. Amphetamine response in rat after dopamine neurone destruction. Nat N Biol. 1972;238:247–4. doi: 10.1038/newbio238247a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creese I, Iversen SD. The pharmacological and anatomical substrates of the amphetamine response in the rat. Brain Res. 1975;83:419–436. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90834-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Boer P, Enrico P, Wright J, Wise LD, Timmerman W, Moor E, Dijkstra D, Wikstrom HV, Westerink BH. Characterization of the effect of dopamine D3 receptor stimulation on locomotion and striatal dopamine levels. Brain Res. 1997;758:83–91. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01438-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz J, Pilon C, Le Foll B, Gros C, Triller A, Schwartz JC, Sokoloff P. Dopamine D3 receptors expressed by all mesencephalic dopamine neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8677–8684. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-08677.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman A, Nissbrandt H, Heilig M, Dijkstra D, Eriksson E. Central administration of dopamine D3 receptor antisense to rat: Effects on locomotion, dopamine release and [3H]spiperone binding. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1998;358:342–350. doi: 10.1007/pl00005263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillin O, Griffon N, Bezard E, Leriche L, Diaz J, Gross C, Sokoloff P. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor controls dopamine D3 receptor expression: Therapeutic implications in Parkinson's disease. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;480:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A, Lachowicz JE, Sibley DR. Phenotypic analysis of dopamine receptor knockout mice; recent insights into the functional specificity of dopamine receptor subtypes. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:1117–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph JD, Wang YM, Miles PR, Budygin EA, Picetti R, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG, Wightman RM. Dopamine autoreceptor regulation of release and uptake in mouse brain slices in the absence of D(3) receptors. Neuroscience. 2002;112:39–49. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce JN. Dopamine D3 receptor as a therapeutic target for antipsychotic and antiparkinsonian drugs. Pharmacol Ther. 2001;90:231–259. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(01)00139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung MY, Skryabin BV, Arai M, Abbondanzo S, Fu D, Brosius J, Robakis NK, Polites HG, Pintar JE, Schmauss C. Potentiation of the D2 mutant motor phenotype in mice lacking dopamine D2 and D3 receptors. Neuroscience. 1999;91:911–924. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00705-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kling-Petersen T, Ljung E, Svensson K. Effects on locomotor activity after local application of D3 preferring compounds in discrete areas of the rat brain. J Neural Transm Gen Sect. 1995;102:209–220. doi: 10.1007/BF01281155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeltzow TE, Xu M, Cooper DC, Hu XT, Tonegawa S, Wolf ME, White FJ. Alterations in dopamine release but not dopamine autoreceptor function in dopamine D3 receptor mutant mice. J Neurosci. 1998;8:2231–2238. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-06-02231.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara FN, Clifford JJ, Tighe O, Kinsella A, Drago J, Fuchs S, Croke DT, Waddington JL. Phenotypic, ethologically based resolution of spontaneous and D(2)-like vs D(1)-like agonist-induced behavioural topography in mice with congenic D(3) dopamine receptor “knockout”. Synapse. 2002;46:19–31. doi: 10.1002/syn.10108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercuri NB, Saiardi A, Bonci A, Picetti R, Calabresi P, Bernardi G, Borrelli E. Loss of autoreceptor function in dopaminergic neurons from dopamine D2 receptor deficient mice. Neuroscience. 1997;79:323–327. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00135-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missale C, Nash SR, Robinson SW, Jaber M, Caron MG. Dopamine receptors: From structure to function. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:189–225. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori T, Murase K, Tanaka J, Ichimaru Y. Biphasic effects of D3-receptor agonists, 7-OH-DPAT and PD128907, on the D1-receptor agonist-induced hyperactivity in mice. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1997;73:251–254. doi: 10.1254/jjp.73.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouagazzal AM, Creese I. Intra-accumbens infusion of D(3) receptor agonists reduces spontaneous and dopamine-induced locomotion. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;67:637–645. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00406-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pijnenburg AJ, Honig WM, Van Rossum JM. Inhibition of d-amphetamine-induced locomotor activity by injection of haloperidol into the nucleus accumbens of the rat. Psychopharmacologia. 1975;41:87–95. doi: 10.1007/BF00421062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard LM, Logue AD, Hayes S, Welge JA, Xu M, Zhang J, Berger SP, Richtand NM. 7-OH-DPAT and PD 128907 selectively activate the D3 dopamine receptor in a novel environment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:100–107. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddle EL, Fleckenstein AE, Hanson GR. Role of monoamine transporters in mediating psychostimulant effects. AAPS J. 2005;7:E847–E851. doi: 10.1208/aapsj070481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridray S, Griffon N, Mignon V, Souil E, Carboni S, Diaz J, Schwartz JC, Sokoloff P. Coexpression of dopamine D1 and D3 receptors in islands of Calleja and shell of nucleus accumbens of the rat: Opposite and synergistic functional interactions. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:1676–1686. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DC, Zis AP, Fibiger HC. Ascending catecholamine pathways and amphetamine-induced locomotor activity: Importance of dopamine and apparent non-involvement of norepinephrine. Brain Res. 1975;93:441–454. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal DS, Kuczenski R. Individual differences in responsiveness to single and repeated amphetamine administration: Behavioral characteristics and neurochemical correlates. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1987;242:917–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal DS, Kuczenski R. Behavioral pharmacology of amphetamine. In: Cho AK, Segal DS, editors. Amphetamine and its analogues: Pharmacology, toxicology, and abuse. Academic Press; Orlando, FL: 1994. pp. 115–150. [Google Scholar]

- Silver LM. Mouse genetics: Concepts and applications. Oxford University Press; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Surmeier DJ, Song WJ, Yan Z. Coordinated expression of dopamine receptors in neostriatal medium spiny neurons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6579–6591. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-20-06579.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallone D, Pignatelli M, Grammatikopoulos G, Ruocco L, Bozzi Y, Westphal H, Borrelli E, Sadile AG. Activity, non-selective attention and emotionality in dopamine D2/D3 receptor knock-out mice. Behav Brain Res. 2002;130:141–148. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00428-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters N, Svensson K, Haadsma-Svensson SR, Smith MW, Carlsson A. The dopamine D3-receptor: A postsynaptic receptor inhibitory on rat locomotor activity. J Neural Transm Gen Sect. 1993;94:11–19. doi: 10.1007/BF01244979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong JY, Clifford JJ, Massalas JS, Finkelstein DI, Horne MK, Waddington JL, Drago J. Neurochemical changes in dopamine D1, D3 and D1/D3 receptor knockout mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;472:39–47. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01862-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, Koeltzow TE, Santiago GT, Moratalla R, Cooper DC, Hu XT, White NM, Graybiel AM, White FJ, Tonegawa S. Dopamine D3 receptor mutant mice exhibit increased behavioral sensitivity to concurrent stimulation of D1 and D2 receptors. Neuron. 1997;19:837–848. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80965-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapata A, Witkin JM, Shippenberg TS. Selective D3 receptor agonist effects of (+)–PD 128907 on dialysate dopamine at low doses. Neuropharmacology. 2001;41:351–359. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Lou D, Jiao H, Zhang D, Wang X, Xia Y, Zhang J, Xu M. Cocaine-induced intracellular signaling and gene expression are oppositely regulated by the dopamine D1 and D3 receptors. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3344–3354. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0060-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]