Abstract

Aminopeptidase N (APN, CD13; EC 3.4.11.2) is a transmembrane metalloprotease with several functions, depending on the cell type and tissue environment. In tumor vasculature, APN is overexpressed in the endothelium and promotes angiogenesis. However, there have been no reports of in vivo inactivation of the APN gene to validate these findings. Here we evaluated, by targeted disruption of the APN gene, whether APN participates in blood vessel formation and function under normal conditions. Surprisingly, APN-null mice developed with no gross or histological abnormalities. Standard neurological, cardiovascular, metabolic, locomotor, and hematological studies revealed no alterations. Nonetheless, in oxygen-induced retinopathy experiments, APN-deficient mice had a marked and dose-dependent deficiency of the expected retinal neovascularization. Moreover, gelfoams embedded with growth factors failed to induce functional blood vessel formation in APN-null mice. These findings establish that APN-null mice develop normally without physiological alterations and can undergo physiological angiogenesis but show a severely impaired angiogenic response under pathological conditions. Finally, in addition to vascular biology research, APN-null mice may be useful reagents in other medical fields such as malignant, cardiovascular, immunological, or infectious diseases.

Keywords: CD13, knockout mice, retinopathy, vasculogenesis

The aminopeptidases are a large family of proteolytic enzymes that affect protein maturation, degradation, and regulation (1, 2). Aminopeptidase N (APN) is a membrane-bound zinc-dependent metalloprotease originally identified as a surface marker in myeloid cells (3, 4). APN is widely distributed in many cell types, and its role in hydrolyzing unsubstituted N-terminal residues with neutral side chains varies in different locations. In the epithelium of the renal proximal tubule, APN cleaves its only known natural substrate, angiotensin (ang) III, to ang IV; in synaptic membranes, APN metabolizes enkephalins and endorphins; in the heart, it is an integral component of cardiac remodeling postmyocardial infarction (5–10); and in the respiratory system, APN is the cell surface receptor for certain human coronaviruses and potentially for the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) virus (11–13). Additionally, APN functions in signal transduction, cell cycle control, and differentiation (14, 15).

We have developed an in vivo system by using ligand peptides displayed on the surface of phage to study organ- and tumor-specific vascular homing; this methodology enables the identification of vascular markers (16, 17). We have isolated phage displaying an asparagine-glycine-arginine (NGR)-containing peptide in a tumor-homing selection and have shown that these phage bind selectively to angiogenic blood vessels. When coupled to a cytotoxic drug (18) or fused to a proapoptotic peptide (19) or to tumor necrosis factor (20), NGR-targeted compounds were more effective and less toxic than the respective controls. The cell surface receptor for NGR-containing ligands was then shown to be APN (21). Of note, although a single gene encodes APN, specific phenotypic forms of APN (CD13) in angiogenic vasculature relative to normal tissues further enhance the targeting attributes of the NGR motif (22).

To evaluate the effects of the APN gene on development and organ function, we produced a knockout mouse lacking APN. This has been technically challenging because of the incomplete genomic characterization and complex APN gene structure. Here we report the generation of an APN-null mouse by homologous recombination and a description of its phenotype. Despite its broad expression, the APN gene is not essential for development, because the null was not embryonically lethal and developed normally. Standard phenotype characterization revealed no differences between WT and APN-null mice. However, in a model of retinal neovascularization, APN-null mice had a significant decrease in blood vessel growth compared with WT. Moreover, gelfoam plug assays demonstrated a reduction in hemoglobin content within the plugs, indicating lack of a functional vasculature. Thus, although APN activity is not essential for embryonic and fetal development including de novo blood vessel formation (i.e., vasculogenesis) and normal adult function, it is critical for the pathological development of new blood vessels from existing blood vessels (i.e., angiogenesis) in disease.

Results

APN-Null Mouse Generation.

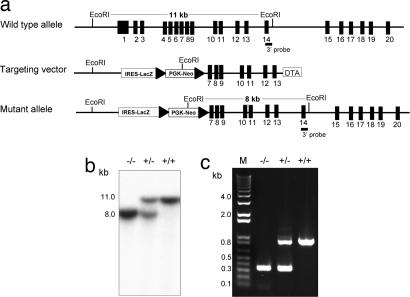

Early attempts to isolate the APN gene have been problematic because of the absence of genomic clones in the 5′ region of the gene. To overcome this limitation, a combined screening of 129S6/SvEv Tac BAC libraries and BLAST analysis served to obtain the complete sequence of the mouse APN gene in a C57BL/6 background. Indeed, previous reports on gene characterization revealed variation in restriction enzyme maps between different genetic backgrounds. Integrated Southern blot and bioinformatics revealed that the APN gene in C57BL/6 and 129Sv/Ev backgrounds possessed the same restriction enzyme map (data not shown). APN exon–intron boundary analysis showed that exon 5 contained the nucleotide sequence that encodes the zinc-binding domain. Thus, our strategy (Fig. 1) was to eliminate expression and enzymatic activity by replacing APN exons 1–6 (Fig. 1a). After mouse embryonic stem (ES) cell screening, we detected 3 of 600 ES cell clones that contained the APN mutant allele; mutant ES clones were injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts and produced a single chimeric mouse, which was used for mating with C57BL/6 mice. After 5 mo, we detected the first germ-line transmission in a 129Sv/Ev-C57BL/6 genetic background. The first three generations of progeny were genotyped by either Southern blot (Fig. 1b) or PCR (Fig. 1c). Despite strong RNA expression during embryogenesis, Mendelian inheritance of the APN-null allele occurred [supporting information (SI) Fig. 8].

Fig. 1.

Generation and characterization of the APN-null mouse. (a) Schema of the APN gene-targeting strategy. The APN gene contains 20 exons (black boxes); the 3′ external probe is located in exon 14. The targeting vector contains a β-galactosidase transgene and a floxed neomycin resistant gene. (b) Southern blot of genomic DNA from WT (+/+), APN-heterozygous (+/−), and APN-null (−/−); the mutant allele (8 kb) and the WT allele (11 kb) are noted. The APN heterozygous contains both alleles. (c) PCR genotyping reveals unique products for WT (879-bp) and APN-null (320-bp) mice. The APN heterozygous contains both PCR products.

Inactivation of APN in the Null Mouse.

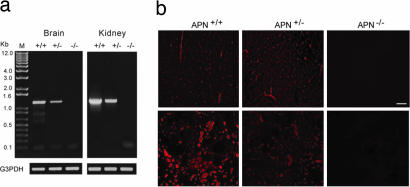

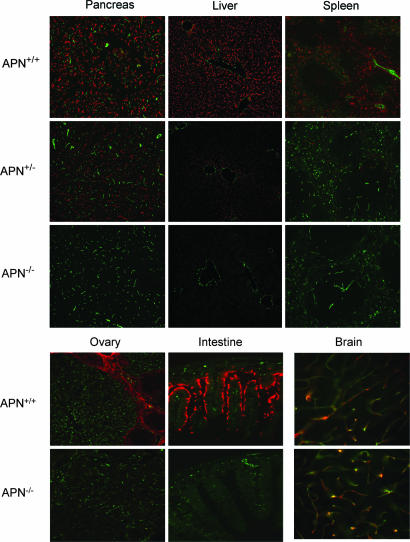

APN expression was examined at the RNA and protein level, focusing initially on the nervous and renal systems, because APN is highly expressed in the pericytes associated with the brain endothelium and in the proximal tubules of the kidney. RT-PCR and immunohistochemical analysis showed a total absence of mRNA and protein in the brain and kidney of APN-null mice (Fig. 2). In contrast, WT mice displayed a strong expression of mRNA and protein in those organs. Similar results were observed in the spleen, liver, pancreas, intestine, and ovary (Fig. 3). Notably, a gene dosage effect was observed for the heterozygous animal (Figs. 2 and 3). Because aminopeptidase A (APA) is another member of the aminopeptidase family with similar expression patterns to that of APN (23), APA expression was examined as a surrogate to ensure that loss of APN did not affect normal tissue organization. Colocalization analysis between WT and the APN-null revealed no change in the expression profile of APA in brain pericytes despite the loss of APN (Fig. 3). These data support the genetic generation of a viable APN-null mouse.

Fig. 2.

Expression analysis of the APN-null mouse. (a) RT-PCR analysis of total RNA. The WT (+/+) and heterozygous (+/−) mice contain the 1.2-kb PCR product representing the APN mRNA transcript that is undetectable in the APN-null mouse (−/−). The G3PDH transcript served as a loading control. (b) Immunohistochemical analysis of the APN protein in brain (Upper) and kidney (Lower). APN immunoreactivity (red fluorescence) is detected in renal tubules and in pericytes within brain vasculature of WT and heterozygous mice but not in the APN-null mice (Right). (Scale bar, 100 μm.)

Fig. 3.

Immunohistochemical analysis of APN and CD31. Colocalization studies in pancreas, liver, and spleen for APN (red fluorescence) and CD31 (green fluorescence) were performed in frozen tissue sections (Upper). The WT and APN-heterozygote mice contain dual fluorescence signals; in APN-null mice, only CD31 immunoreactivity is detected. Ovary and intestine were also evaluated (Lower Left). Brain was costained with anti-CD31 and -APA antibodies. The yellow fluorescence reflects the localization of both proteins in pericytes in brain vasculature (Lower Right).

Histopathological Studies in the APN-Null Mouse.

A comprehensive panel of organs of 12-wk-old male and female mice was examined in H&E-stained sections. No structural differences were found between WT and APN-null mice (SI Fig. 9 a–d). Blood counts showed no differences in all parameters (SI Table 1), and serum chemistries indicated there were no significant electrolyte imbalances between WT and APN-null mice (SI Table 2). These results are consistent with full APN-null mouse viability.

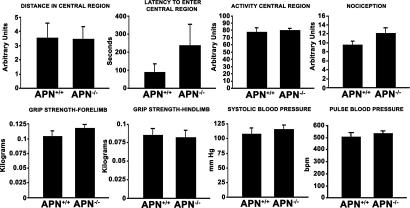

Noninvasive Phenotypic Studies in the APN-Null Mouse.

The function of APN appears to depend on its tissue localization. Thus, system functions (i.e., neurological, cardiovascular, metabolic, and locomotor) were compared to explore whether the deficiency of APN altered physiology (Fig. 4). First, activity tests were performed in an open field to determine any behavioral alterations in the APN-null mouse. Data were plotted for the time required for the mice to reach the central region, latency to enter it, and activity within that area of the field. No statistically significant differences in behavior were found. Next, neuromuscular function was assessed by muscle grip strength and showed no differences between the two groups. Finally, thermal and pain reflexes were assessed when the APN-null mouse footpad was placed against a heated surface; we noted a small increase in pain resistance when compared with the WT mouse (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Noninvasive phenotypic studies. Spontaneous locomotor activity in WT mice and APN-null littermates are represented as distance in central region, latency central region, and activity central region. Nociception was measured by using a hot-plate analgesia meter. Neuromuscular function was determined by grip strength of the forelimb and hindlimb. Pulse and blood pressure were measured by the tail-cuff method. Error bars indicate SEM of WT and APN-null mice (n = 6 per group).

Noninvasive tail cuff measurements were used for blood pressure and pulse measurements. APN-null mice had normal baseline pulse and blood pressure (Fig. 4). Cardiovascular analysis by noninvasive unrestrained measurements revealed no statistical differences in baseline electrocardiogram heart rate and its variability or waveform intervals (SI Figs. 10 a and b). These data indicate that APN is not critical in regulation of cardiovascular function under normal conditions.

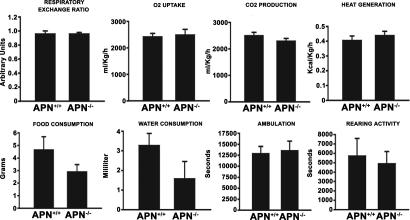

Body composition and whole-body metabolism served as surrogates for endocrine and renal function. Bone mineral density, content, and body fat content were measured by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry. No statistically significant differences between the two groups of mice were found (SI Fig. 11). Moreover, comprehensive in-cage monitoring was performed for O2 uptake, CO2 production, food and water intake, locomotor activity, and circadian patterns to assess total body metabolism and energy balance. Results revealed a trend toward reduction in food and water intake for the APN-null mouse, but the results did not reach statistical significance; all other measures were similar between the two groups (Fig. 5). Thus, under normal conditions, WT and APN-null mice have similar behavioral phenotypes and physiological regulation. Null female mice were fertile and carried normal numbers of progeny through full pregnancy and nursing phases.

Fig. 5.

Comprehensive in-cage monitoring system. The WT and APN-null mice littermates were examined for respiratory exchange ratio, oxygen uptake, and carbon dioxide production. Caloric intake and energy metabolism were measured for heat production, food, and water consumption. Ambulation and rearing activity were determined by using the comprehensive laboratory animal-monitoring system. Error bars indicate SEM of WT and APN-null mice (n = 6 per group).

Reduced Angiogenesis in the APN-Null Mouse.

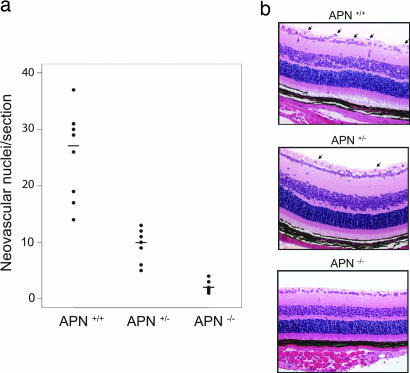

We next evaluated whether the APN-null mouse had a normal angiogenic response to hypoxic conditions. Neonatal mice were exposed to 75% oxygen between postnatal days (P)7–P12 and then returned to room air. By P18, retinal neovascularization is observed in WT mice; in contrast, histological examination of similarly treated APN-null mice revealed a marked reduction in the formation of new blood vessels at the retinal inner surface compared with the response in WT mice (Fig. 6). Consistently, an intermediate dose response was observed in the APN heterozygotes. Thus, the APN-null mouse has a severely reduced angiogenic response to hypoxic conditions.

Fig. 6.

Failed retinal neovascularization in APN-null mice under hypoxic conditions. (a) Quantification of endothelial cells nuclei extended across the inner surface of the retina into the vitreous space. Data from WT, APN-heterozygous, and APN-null mice were compared (P < 0.001). (b) APN-null mice lack the nuclei protruding into the vitreous space of the eye, as observed in the WT and heterozygote representative examples (arrows). Five independent experiments were performed with similar results.

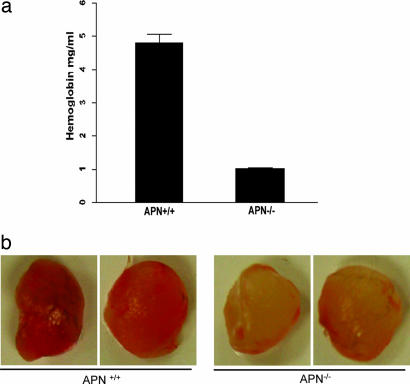

Next, angiogenic responses to growth factors in vivo were tested by s.c. implanting gelfoam sponges saturated with VEGF, basis FGF, and TGF-α. To quantify vascularization, hemoglobin concentrations were compared (Fig. 7). Plugs from WT mice contained ≈5-fold more hemoglobin than those from APN-null mice. These results show that APN deficiency reduces the angiogenic response and supports a role in pathological angiogenesis.

Fig. 7.

APN-null mice have severely impaired angiogenesis upon growth factor stimulation. (a) Hemoglobin content of the gelfoam from WT and APN-null mice were analyzed. (b) Gelfoam plugs implanted in the s.c. tissue were removed after 14 days and analyzed. Plugs in WT mice contained significantly more hemoglobin (4.8 ± 0.3 mg/ml) than those in APN−/− mice (1.0 ± 0.1 mg/ml; P < 0.0001). Five independent experiments were performed with similar results.

Discussion

This study reports the generation of an APN-null mouse and an evaluation of its phenotype. APN-null mice exhibit no developmental, fertility, or behavioral or physiological abnormalities. Interestingly, inactivation of APN gene expression impaired the formation of new blood vessels under pathological conditions. The genetic results presented here not only expand the knowledge of APN in angiogenesis but also provide a tool to study APN function in other fields.

Angiogenesis is critical to pathological conditions, including cancer, inflammation, and retinopathies (21, 24, 25). The present study shows that APN-null mice display a severely impaired angiogenic response to oxygen-induced retinopathy and respond far less strongly to angiogenic growth factors in vivo than do WT animals. These data are consistent with our original biochemical observation regarding a functional role for APN in angiogenesis, where the administration of blocking antibodies or chemical inhibitors of APN suppressed new blood vessel formation in several mouse models (21). Shapiro and colleagues later showed that APN is transcriptionally activated by angiogenic signals, mediated by the renin-ang system /MAPK/Ets-2 signaling pathway, and essential for endothelial morphogenesis and capillary tube formation (26–28). Recently, by using RNA interference, Fukasawa et al. (29) confirmed that APN is selectively expressed in vascular endothelial cells, and that the enzyme plays multiple roles in angiogenesis. These results (21, 26–29) are in agreement with our findings in the APN-null mouse. However, future experiments are required to determine the precise downstream mechanism(s) through which APN regulates neovascularization. Indeed, APN-null mice develop normally despite strong gene expression during embryogenesis. These contrasting observations indicate that APN is not an essential enzyme for vasculogenesis during development and suggest genetic redundancy or compensation. Of note, similar angiogenic defects were observed in the APA-null mouse, suggesting that both aminopeptidases are required for new blood vessel formation (30). Furthermore, APA and APN serially cleave molecules of the renin–ang system: APA cleaves ang II into ang III, and APN cleaves ang III into ang IV (31). It is tempting to speculate that ang IV is an angiogenic molecule; thus, an enzymatic deficiency (in APN or APA) could ultimately limit the generation of ang IV and be one possible mechanism leading to reduced angiogenesis in APN-null mice. It is also plausible that other substrate(s) might exist. Interestingly, in pilot experiments, wound-healing assays showed no significant differences between WT and APN-null mice (unpublished results); these results, along with the observed normal fertility and litter sizes suggest that physiological angiogenesis is not affected in APN-null mice. The phenotype in the double (APN/APA)-null mouse remains to be determined; these experiments are ongoing.

Remarkably, APN-null mice have no apparent alterations in blood pressure or electrolytes. These findings are somewhat unexpected, because increased levels of ang III alter water balance and blood pressure (31–33). One possible reason why hemodynamics and electrolyte homeostasis remain normal with no APN activity may be that a mouse homologue of the human adipocyte-derived leucine aminopeptidase (A-LAP) can directly cleaves ang II to produce ang IV (34). The expression of mouse A-LAP is yet to be measured, but it could conceivably compensate for decreased production of ang IV in APN-null mice.

Several reports have demonstrated that enkephalins are neuropeptides cleaved by APN (35–37). Enkephalins are predominantly detected in the thalamus and spinal cord and regulate pain perception, memory, and satiety (38, 39). Experimental manipulation of the brain renin–ang system has shown that exogenous administration of high doses of ang III can modify thirst and sodium appetite, and that doses of ang IV can alter learning and memory (40, 41). Recently, proteomic analysis revealed that APN hydrolyzed leucine and methionine enkephalins in exosomes of microglial cells (42). In line with these studies, a subtle trend toward reduction of water and food consumption was noted in APN-null mice. Although modest, these data suggest that the catabolism of enkephalins might be slightly altered in the APN-null mouse, but that redundancy or compensatory mechanisms are present. Moreover, the APN-null mouse has a small but significantly increased tolerance to heat and pain stimuli. These data again support the enzymatic role of APN in inactivation of enkephalin, leading to pain resistance. However, more refined neurological experiments are needed to better define these minor phenotypes.

Additional insights into APN function may be gained by considering its role as a cell surface receptor for human coronaviruses (11, 12). The SARS virus is a coronavirus that produces severe respiratory infection in patients (43). The mechanism of SARS virus internalization is through binding to the host receptors ACE-2 and L-SIGN (CLEC4M/CD209) in lung epithelial cells (44, 45); we (13) and other investigators (44, 45) have speculated that APN may be a coreceptor for the SARS virus. Because APN is expressed in the lung epithelium, it is worthwhile to evaluate the APN-null mouse as an experimental model for SARS or other coronavirus-induced human diseases.

In summary, we generate and describe the phenotype of an APN-null mouse. Despite the broad range of APN functions, APN-null mice develop and function normally. However, our results provide a clear role for APN in angiogenesis under pathological conditions and provide a genetic model to explore further the role of this enzyme in other biological processes.

Materials and Methods

Generation of Knockout Mice.

Commercially available BAC mouse 129S6/SvEv Tac genomic libraries (Research Genetics, Huntsville, AL) were screened by using a 32P-labeled APN cDNA probe. Filters were hybridized at 60°C, washed, and exposed for 4 h at −80°C on x-ray films. Bioinformatics and Southern blot analysis were used to characterize the Anpep gene and generate a restriction map for the gene targeting strategy. The 5′ and 3′ arms of homology of the targeting vector (4.5- and 5.5-kb, respectively) were obtained by PCR (Expand Long PCR template kit; Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and confirmed by DNA sequencing. A diphtheria toxin gene driven by the pMC1 promoter was cloned at the 3′ end of the construct for negative selection. The targeting vector was linearized by NotI and electroporated into mouse ES cells. DNA from neomycin-resistant ES cell colonies was digested by EcoRI (Roche), separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, blotted onto nylon membranes, and hybridized with a 250-bp external probe. Homologous recombination events were identified by Southern blot (11-kb, WT allele; 8-kb, mutant allele). Targeted ES cell clones were injected into the blastocyst of C57BL/6 mice, and a single chimeric mouse was intercrossed with C57BL/6 mice to establish a germ-line transmission. This study adhered to the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmology and Vision Research. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center Animal approved all experimentation.

Genotyping.

Genotyping was performed by Southern blot and PCR with three primer combinations: forward, 5′-CACCCCCATCCCCCATCCCTTAC-3′; reverse, 5′-GTGCCCACGCCCTTGAACCTTACTT-3′; and IRES-rev, 5′-ACAAACGCACACCGGCCTTATTCC-3′. PCR with the forward/reverse and forward/IRES-rev primer pairs generated an 879-bp WT product and a 320-bp mutant product. For PCR-based genotyping, a hot-start (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) initial step of denaturation (95°C for 15 min) was then followed by 35 cycles (denaturation, 94°C for 30 s; annealing, 65°C for 1 min; extension at 68°C for 1 min).

RT-PCR.

Mice were killed by cervical dislocation and tissues removed and incubated in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad CA) for total RNA isolation. cDNA was obtained with the reverse transcriptase (RT) superScript III kit (Invitrogen). To detect the expression of the APN transcript, we used the PCR primers: forward 5′-CCCCGGGGCTGCTGTTCTTT-3′ and reverse 5′-ACCACCCGCTCCTTGTTGCTAATG-3′. PCR amplification consisted of an initial step (94°C for 3 min) followed by 35 cycles (94°C for 30 s, 65°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min). The housekeeping gene glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH) served as an internal loading control.

Histopathology.

Three- and 6-mo-old WT and APN-null male and female mice (at least three mice on each group) were used for histopathological analysis. Blood samples were collected for hematology and serum chemistry studies from each mouse.

Tissue Processing and Immunohistochemistry.

WT (APN+/+), heterozygous (APN+/−), and null (APN−/−) mice were anesthetized with Avertin and perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4). Organs were removed, incubated in the same fixative solution for 1 h, and then infiltrated with 30% sucrose in PBS containing 0.002% sodium azide overnight at 4°C. The next day, the organs were frozen in OCT and stored at −80°C. Frozen tissue sections were cut, air-dried on slides, rinsed twice for 5 min with PBS and once with PBS containing 1% Triton X-100 (PBST), and then blocked with 5% normal goat serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) in PBST for 30 min. Tissue sections were incubated for 1 h in primary antibody solution containing monoclonal Armenian hamster anti-CD31 (1:500 dilution, clone 2H8; Chemicon, Temecula, CA), monoclonal rat anti-CD13 (1:500 dilution, clone R3–63; Serotec, Raleigh, NC), and 1% normal goat serum in PBST. Slides were then rinsed three times with PBST for 5 min each and incubated for 30 min with a 0.45-μm-filtered secondary antibody solution containing FITC-conjugated goat anti-hamster IgG (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch) and Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG (1:400; Jackson ImmunoResearch) in PBST. Finally, slides were rinsed three times for 5 min each with PBST, fixed with 4% PFA in PBS for 1 min, rinsed three times with PBS for 5 min each, and mounted (Vectashield; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA).

Noninvasive Phenotypic Analysis.

Age- and sex-matched WT, heterozygous, and null (n = 6/group) were evaluated for fertility, litter size, locomotor activity, nociception, grip strength, blood pressure, in-cage comprehensive monitoring system, dual energy x-ray absorptiometry, and electrocardiogram.

Retinal Neovascularization Assay.

Mice were exposed to 75% oxygen (P7–P12) and killed (P19). Eyes were enucleated and fixed in Bouin's solution. Tail snips were taken to determine the genotype. Fixed and alcohol-dehydrated eyes were embedded in paraffin, serially sectioned and H&E-stained. Endothelial cell nuclei on the vitreous side of the internal limiting membrane were counted.

In Vivo Angiogenesis Assay.

To induce the formation of new blood vessels in vivo, gelfoam sponges (Johnson & Johnson, Somerville, NJ) were saturated with growth factors (200 ng/ml each; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) including VEGF, basis FGF, and TGF-α. Sponges were implanted s.c. After 14 days, mice were killed, and gelfoams were homogenized and incubated with Drabkin's reagent (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Hemoglobin content was reported as mean ± SEM. WT, heterozygous, and null mice were compared.

Statistical Analysis.

An ANOVA test of variance served to determine significant differences among multiple groups. Paired t test comparisons were used for applied posthoc analysis and adjusted by Bonferroni correction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Jan Parker-Thornburg, Amin Hajitou, Siew-Sim Cheah, and Glauco R. Souza for discussions and technical assistance. R.R. is a Scholar from the Odyssey Program at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Defense and by an award from the Gillson–Longenbaugh Foundation (to W.A. and R.P.).

Abbreviations

- APN

aminopeptidase N

- ang

angiotensin

- SARS

severe acute respiratory syndrome

- ES

embryonic stem

- APA

aminopeptidase A

- Pn

postnatal day n.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0611653104/DC1.

References

- 1.Hooper NM, Lendeckel U, editors. Aminopeptidases in Biology and Disease. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrett AJ, Rawlings ND, Woessner JF, editors. Handbook of Proteolytic Enzymes. London: Elsevier; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amoscato AA, Alexander JW, Babcock GF. J Immunol. 1989;142:1245–1252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Favaloro EJ, Bradstock KF, Kabral A, Grimsley P, Zowtyj H, Zola H. Br J Haematol. 1988;69:163–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1988.tb07618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mechtersheimer G, Moller P. Am J Pathol. 1990;137:1215–1222. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menrad A, Speicher D, Wacker J, Herlyn M. Cancer Res. 1993;53:1450–1455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riemann D, Kehlen A, Langner J. Immunol Today. 1999;20:83–88. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5699(98)01398-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lalu K, Lampelo S, Vanha-Perttula T. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;873:190–197. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(86)90045-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chansel D, Czekalski S, Vandermeersch S, Ruffet E, Fournie-Zaluski MC, Ardaillou R. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:535–542. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.275.4.F535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsas R, Turner AJ, Kenny AJ. FEBS Lett. 1984;175:124–128. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(84)80583-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delmas B, Gelfi J, L'Haridon R, Sjöström H, Norén O, Laude H. Nature. 1992;357:417–420. doi: 10.1038/357417a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeager CL, Ashmun RA, Williams RK, Cardellichio CB, Shapiro LH, Look AT, Holmes KV. Nature. 1992;357:420–422. doi: 10.1038/357420a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kontoyiannis DP, Pasqualini R, Arap W. The Lancet. 2003;361:1558. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13186-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santos AN, Langner J, Herrmann M, Riedmann D. Cell Immunol. 2000;201:22–32. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2000.1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mina-Osorio P, Ortega E. J Leukocyte Biol. 2005;77:1008–1017. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1204714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hajitou A, Pasqualini R, Arap W. Trends Cardivasc Med. 2006;16:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sergeeva A, Kolonin MG, Molldrem JJ, Pasqualini R, Arap W. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006;58:1622–1654. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arap W, Pasqualini R, Ruoslahti E. Science. 1998;279:377–380. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellerby HM, Arap W, Ellerby LM, Kain R, Andrusiak R, Rio GD, Krajewski S, Lombardo CR, Rao R, Ruoslahti E, et al. Nat Med. 1999;5:1032–1038. doi: 10.1038/12469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curnis F, Sacchi A, Borgna L, Magni F, Gasparri A, Corti A. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:1185–1190. doi: 10.1038/81183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pasqualini R, Koivunen E, Kain R, Lahdenranta J, Sakamoto M, Stryhn A, Ashmun RA, Shapiro LH, Arap W, Ruoslahti E. Cancer Res. 2000;60:722–727. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curnis F, Arrigoni G, Sacchi A, Fischetti L, Arap W, Pasqualini R, Corti A. Cancer Res. 2002;62:867–874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mentzel S, Dijkman HBPM, Van Son JPHF, Koene RAP, Assmann KJM. J Histochem Cytochem. 1996;44:445–461. doi: 10.1177/44.5.8627002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Folkman J. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:1–18. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.121304.131306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lahdenranta J, Pasqualini R, Schlingemann RO, Hagedorn M, Stallcup WB, Bucana CD, Sidman RL, Arap W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10368–10373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181329198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhagwat SV, Petrovic N, Okamoto Y, Shapiro LH. Blood. 2003;101:1818–1826. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petrovic N, Bhagwat SV, Ratzan WJ, Ostrowski MC, Shapiro LH. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49358–49368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308071200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhagwat SV, Lahdenranta J, Giordano R, Arap W, Pasqualini R, Shapiro LH. Blood. 2001;97:652–659. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.3.652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fukasawa K, Fujii H, Saitoh Y, Koizumi K, Aozuka Y, Sekine K, Yamada M, Saiki I, Nishikawa K. Cancer Lett. 2006;243:135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marchiò S, Lahdenranta J, Schlingemann RO, Valdembri D, Wesseling P, Arap MA, Hajitou A, Ozawa MG, Trepel M, Giordano RJ, et al. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:151–162. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reaux A, Fournie-Zaluski MC, Llorens-Cortes C. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2001;12:157–162. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00381-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faber F, Gembardt F, Sun X, Mizutani S, Siems W-E, Walter T. Regul Pept. 2006;136:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wright JW, Tamura-Myers E, Wilson WL, Roques BP, Llorens-Cortes C, Speth RC, Harding JW. Am J Physiol. 2002;284:725–733. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00326.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goto Y, Hattori A, Ishii Y, Tsujimoto M. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:1833–1838. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gros C, Giros B, Schwartz JC. Biochemistry. 1985;24:2179–2185. doi: 10.1021/bi00330a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Churchill L, Bausback HH, Gerritsen ME, Ward PE. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987;923:35–41. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(87)90122-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giros B, Gros C, Solhonne B, Schwartz JC. Mol Pharmacol. 1986;29:281–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holden JE, Jeong Y, Forrest JM. AACN Clin Issues. 2005;16:291–301. doi: 10.1097/00044067-200507000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lullmann H, Mohr K, Ziegler A, Bieger D. Color Atlas of Pharmacology. Stuttgart, Germany: Thieme; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilson WL, Roques BP, Llorens-Cortes C, Speth RC, Harding JW, Wright JW. Brain Res. 2005;1060:108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Albiston AL, McDowall SG, Matsacos D, Sim P, Clune E, Mustafa T, Lee J, Mendelsohn FAO, Simpson RJ, Connolly LM, Chai SY. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48623–48626. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100512200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Potolicchio I, Carven GJ, Xu X, Stipp C, Riese RJ, Stern LJ, Santambrogio L. J Immunol. 2005;175:2237–2243. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yeung KS, Yamanaka GA, Meanwell NA. Med Res Rev. 2006;26:414–433. doi: 10.1002/med.20055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li W, Moore MJ, Vasilieva N, Sui J, Wong SK, Berne MA, Somasundaran M, Sullivan JL, Luzuriaga K, Greenough TC, et al. Nature. 2003;426:450–454. doi: 10.1038/nature02145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chan VSF, Chan KYK, Chen Y, Poon LLM, Cheung ANY, Zheng B, Chan K-H, Mak W, Ngan HYS, Xu X, et al. Nat Gen. 2006;38:38–46. doi: 10.1038/ng1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.