Abstract

During spindle pole body (SPB) duplication, the new SPB is assembled at a distinct site adjacent to the old SPB. Using quantitative fluorescence methods, we studied the assembly and dynamics of the core structural SPB component Spc110p. The SPB core exhibits both exchange and growth in a cell cycle-dependent manner. During G1/S phase, the old SPB exchanges ∼50% of old Spc110p for new Spc110p. In G2 little Spc110p is exchangeable. Thus, Spc110p is dynamic during G1/S and becomes stable during G2. The SPB incorporates additional Spc110p in late G2 and M phases; this growth is followed by reduction in the next G1. Spc110p addition to the SPBs (growth) also occurs in response to G2 and mitotic arrests but not during a G1 arrest. Our results reveal several dynamic features of the SPB core: cell cycle-dependent growth and reduction, growth in response to cell cycle arrests, and exchange of Spc110p during SPB duplication. Moreover, rather than being considered a conservative or dispersive process, the assembly of Spc110p into the SPB is more readily considered in terms of growth and exchange.

INTRODUCTION

The centrosome organizes microtubules in the cell and orchestrates chromosome segregation during mitosis and meiosis. The centrosome is duplicated once and only once each cell cycle to organize a bipolar spindle required for successful partitioning of the DNA. Each centrosome nucleates spindle microtubules, which attach to the kinetochores, and astral microtubules, which position the spindle. The functional equivalent of the centrosome in yeast, the spindle pole body (SPB), organizes both the spindle and cytoplasmic (equivalent to astral) microtubules throughout the cell cycle from its position anchored in the nuclear envelope. The SPB is a gigadalton macromolecular structure composed of six electron-dense layers arranged in a stack spanning the nuclear envelope (Bullitt et al., 1997; O'Toole et al., 1999). The central plaque is anchored in the plane of the nuclear envelope, the outer plaque nucleates the cytoplasmic microtubules, and the inner plaque nucleates the spindle microtubules in the nucleus. The vertical dimension of the SPB remains constant but the lateral dimension can vary (Bullitt et al., 1997).

The major components of the SPB have been identified and localized, and their arrangement has been defined by tomography and cryoelectron microscopy. The core of the SPB remains after removal of the microtubules and includes Spc42p, Spc110p, Spc29p, calmodulin, Nud1p, and Cnm67p (Adams and Kilmartin, 1999). Spc42p is thought to play an organizational role in the structure and forms a crystalline array on the cytoplasmic side of the central plaque (Bullitt et al., 1997). Spc110p is a coiled-coil protein with a central rod and globular N- and C-terminal domains (Kilmartin et al., 1993). The C terminus of Spc110p binds to Spc42p in the central plaque (Adams and Kilmartin, 1999), whereas the N terminus of Spc110p binds to the Tub4p complex in the inner plaque. Thus, Spc110p is the nuclear anchor of the Tub4p complex and a core structural component of the SPB.

The cytology of the SPB duplication process has been carefully detailed (Byers and Goetsch, 1975; Adams and Kilmartin, 1999). SPB assembly begins in the cytoplasm on the distal tip of the half bridge with formation of the satellite. The half bridge is a modified nuclear envelope structure, composed of several electron-dense layers, that remains attached to the SPB throughout the cell cycle (O'Toole et al., 1999). The satellite first occurs as an electron-dense sphere and contains the cytoplasmic SPB components Spc42p, Cnm67p, Nud1p, and Spc29p (Adams and Kilmartin, 1999). The satellite grows laterally and forms the duplication plaque. Next, the bridge bends and the duplication plaque inserts into the nuclear envelope. The nuclear component Spc110p associates with the nascent SPB after insertion (Adams and Kilmartin, 1999). The duplicated SPBs are in a side-by-side configuration connected by a full bridge until the bridge cleaves and the poles move apart as the mitotic spindle forms.

Duplication of the SPB, like DNA replication, occurs once each cell cycle. The classic experiments by Meselson and Stahl determined that DNA replication is semiconservative with only the new strand incorporating nucleotides each cell cycle. Their study suggested a paradigm in which to view the cell cycle-regulated assembly of macromolecular structures. In conservative assembly, only the new structure assembles new components and the old structure retains old components. In dispersive assembly, both the old and new structures assemble a mixture of new and old components. Centrioles duplicate conservatively: each centrosome contains a centriole pair, and the daughter centriole incorporates newly labeled tubulin, whereas the mother centriole does not (Kochanski and Borisy, 1990). Similarly, Spc42p was recently shown to assemble conservatively into the SPB (Pereira et al., 2001). Herein, we examine the assembly of a nuclear component of the SPB, Spc110p. We find that the classic paradigm of conservative or dispersive assembly does not serve well to describe the many dynamic aspects of Spc110p assembly. Instead, we suggest that assembly of subunits into the SPB can best be considered in terms of growth and exchange. Growth is the addition of new subunits and exchange is the replacement of old subunits with new subunits. Exchange occurs during G1/S and growth occurs late in the cell cycle. The G2 SPB is stable. Moreover, the SPB responds differently to different cell cycle arrests; it shrinks during arrest in G1 with mating pheromone and grows during a variety of G2 and M arrests. Our results suggest an SPB that is more dynamic than previously appreciated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media and Strains

YPD medium was described previously (Geiser et al., 1991). YPR is YPD with 2% raffinose substituted for 2% dextrose. SD-met is SD medium (Sherman et al., 1986; Davis, 1992) supplemented with 1× amino acid mix without methionine, 50 μg/ml adenine, and 25 μg/ml uracil. The complete 100× amino acid mix was described previously (Geiser et al., 1991). SD-met+met is SD-met supplemented with 300 μg/ml methionine.

Strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. All strains are derived from W303. Yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) C-terminal fusions were made by amplifying the YFP-His3MX6 cassette from pDH5 (a gift from Yeast Resource Center, University of Washington, Seattle, WA) and integrating it in frame at the 3′ end of SPC110 (Wach et al., 1997). Cyan fluorescent protein (CFP), green fluorescent protein (GFP), and red fluorescent protein (RFP) C-terminal fusions were made similarly using plasmids pDH3 (a gift from Yeast Resource Center), pFA6a-GFPS65T-kanMX6 or pFA6a-GFPS65T-His3MX6 (Wach et al., 1997), and pTY24, respectively, as templates. Oligonucleotides used for SPC110 fusions were TY18 (5′-CGA ATA CTA AGA GAT AGA ATT GAG AGT AGC AGC GGG CGT ATA TCT TGG GGT CGA CGG ATC CCC GGG) and TY19 (5′-GTA GGA GTC GAT GTA CAT ACG AGA AAT ATG ATG ATA GAG TAA GCG ATA ATC GAT GAA TTC GAG CTC G).

Table 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Name | Genotype |

|---|---|

| W303 | ade2-1oc can1-100 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 |

| CRY1 | Mata |

| DHY15 | MataSPC110::YFP-His3MX6 |

| TYY69-2A | MataSPC110::CFP-kanMX6 LEU2::MET3-SPC110::YFP-His3MX6 |

| TYY80-5A | MataSPC110::YFP-His3MX6 LEU2::MET3-SPC110::YFP-His3MX6 |

| TYY85-3D | MataSPC110::GFP-His3MX6 ade3Δ100 |

| TYY92-18B | MataSPC110::YFP-His3MX6 cdc13-1 LEU2::MET3-SPC110::YFP-His3MX6 |

| TYY93-16D | MataSPC110::YFP-His3MX6 cdc16-1 LEU2::MET3-SPC110::YFP-His3MX6 |

| TYY98 | Mata/Mata/Matα/Matα SPC110::YFP-His3MX6/SPC110::YFP-His3MX6/SPC::YFP-His3MX6/SPC11 0::YFP-His3MX6 |

| TYY99 | Mata/Mata/Matα/Matα SPC110::YFP-His3MX6/SPC110::YFP-His3MX6/SPC110::YFP-His3MX6/ SPC110::CFP-kanMX6 ADE3/ADE3/ADE3/ade3Δ100 TRP1/trp1-1/ttrp1-1/ trp1-1 |

| TYY100 | Mata/Mata/Matα/ Matα SPC110::YFP-His3MX6/SPC110::YFP-His3MX6/SPC110::CFP-kanMX6 /SPC110::CFP-kanMX6 ADE3/ADE3/ade3Δ 100/ade3Δ100 TRP1/TRP1/ trp1-1/ trp1-1 |

| TYY101 | Mata/Mata/Matα/Matα SPC110::YFP-His3MX6/SPC110::CFP-kanMX6/SPC110::CFP-kanMX6/ SPC110::CFP-kanMX6 ADE3/ade3Δ100/ade3Δ100/ade3Δ100 TRP1/TRP1/TRP1/trp1-1 |

| TYY102-5D | MataSPC110::YFP-His3MX6 LEU2::MET3 SPC110::YFP-His3MX6 URA3::GAL-myc-MPS1 |

| TYY109 | MataSPC110::YFP-His3MX6 cdc15-2 |

| TYY110 | MataSPC110::YFP-His3MX6 cdc23-1 |

| TYY113 | Mata/Matα SPC110::GFP-His3MX6/SPC110::GFP-kanMX6 |

| TYY115-2D | Mata ade3Δ100 CYH2s SPC110::RFP-kanMX6/SPC110 |

Strains have the W303 genotype, with the exceptions noted.

Tetraploid strains were created by mating Mata/Mata and Matα/Matα diploids created by using pGALHO. TYY98 was made by mating TYY60 (Mata/Mata SPC110::YFP-His3MX6/SPC110::YFP-His3MX6), and TYY96 (Matα/Matα SPC110::YFP-His3MX6/SPC110::YFP-His3MX6). TYY99 was made by mating TYY60 and TYY95 (Matα/Matα SPC110::YFP-His3MX6/SPC110::CFP-kanMX6 ADE3/ade3Δ100 TRP1/trp1-1). TYY100 was made by mating TYY94 (Mata/Mata SPC110::YFP-His3MX6/SPC110::CFP-kanMX6 ADE3/ade3Δ 100 TRP1/trp1-1) and TYY95. TYY101 was made by mating TYY95 and TYY97 (Mata/Mata SPC110::CFP-kanMX6/SPC110::CFP-kanMX6 ade3Δ100/ade3Δ100 TRP1/TRP1). The tetraploid strains exhibited marker loss consistent with previously observed levels of chromosome loss in tetraploid Saccharomyces cerevisiae (1000-fold higher than diploids) (Mayer and Aguilera, 1990). Therefore, tetraploid cells were imaged after minimal culturing.

Strains containing LEU2::MET3 SPC110::GFP-kanMX6 were made by integrating pMM80 linearized with BstEII at the LEU2 locus.

Plasmids

pTY24 was made by cloning polymerase chain reaction-amplified RFP from plasmid pDsRed.T1.N1 (Bevis and Glick, 2002) into pFA6a-GFPS65T-kanMX6 (Wach et al., 1997), replacing the green fluorescent protein (GFP) with RFP. DsRed.T1.N1 has a shorter half-life (0.70 h) than DsRed1 (11 h) used in the Pereira et al. study of Spc42p (Pereira et al., 2001; Bevis and Glick, 2002). pGALHO was used to switch mating types. pMM80 (a gift from M. Moser, EraGen Biosciences, Madison, WI) was created by three-way ligation of SalI/NcoI MET3 promoter fragment from pMM77 and an NcoI/NotI SPC110 fragment (corresponding to the open reading frame plus ∼1.3 kb downstream) into SalI/NotI site in pRS305 (Sikorski and Hieter, 1989). pMM77 was created by insertion of eight base pairs of NcoI linker into pHAM8 (a gift from H. Mountain, University of Umea, Umea, Sweden) cut with EcoRV. pTY39 was created by integration of the polymerase chain reaction-amplified GFP-kanMX6 cassette at the 3′ end of SPC110 encoded on pHS72. pHS72 was made by cloning an NcoI-SnaB1 SPC110-containing fragment into the NcoI-SnaB1 sites of pHS70, placing it under control of the GAL10 promoter. To construct the plasmid pHS70, plasmid pSJ101 (Mathias et al., 1996) was digested with NheI and reclosed to remove lacZ.

Westerns

Spc110p blots were incubated overnight in a 1% nonfat milk solution containing a 1:1000 dilution of affinity-purified Spc110p polyclonal antibodies (Friedman et al., 1996). Immunoblots were developed using goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:3000; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and the ECL+plus chemiluminescence system (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Western blots were scanned on a Molecular Dynamics Storm imager and quantified using the IQMacv1.2 version of the accompanying software.

Synchronizations and MET3 Inductions

Centrifugal elutriation was carried out as described previously (Sundberg et al., 1996), except cultures were grown to 200 Klett units in YPD medium (6 × 107 cells/ml) and released at 30°C. α-Factor arrests were performed on an asynchronous culture in early logarithmic phase. Cells were arrested for 1.5 generations (2 h 15 min at 30°C) by adding α-factor (Bio-Synthesis, Lewisville, TX) to a final concentration of 4 μM. Cells were collected by filtration and washed three times with 1 volume of medium at 30°C and resuspended in 30°C medium. For the α-factor methionine pulse inductions, cells were α-factor arrested in SD-met+met as described above and collected by filtration and washed three times with 1 volume of SD-met at 30°C, resuspended in 30°C SD-met with fresh α-factor, and incubated for 90 min. Cells were then released from arrest by being washed three times with 1 volume of 30°C SD-met+met and resuspended in SD-met+met.

Deconvolution Fluorescence Microscopy and Fluorescence Intensity Quantification of SPBs

Cells were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for 15 min at 30°C in a roller drum, washed two times in phosphate-buffered saline, and mounted with polylysine on 1.5-mm coverslips. Most cells were imaged by using a DELTAVISION deconvolution microscopy system from Applied Precision (Issaquah, WA), which incorporates an Axiovert microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) with a 63× oil objective. The images were captured using a Quantix-LC cooled charge-coupled device video camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ) and analyzed by using DELTAVISION SoftWoRx software. Other images were captured using a DELTAVISION system incorporating an IL-70 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), a u-plan-apo 100× oil objective (1.35 numerical aperture), a CoolSnap HQ digital camera from Roper Scientific (Tucson, AZ), and optical filter sets from Omega Optical (Battleboro, VT).

For fluorescence intensity quantification, a z-stack of 15 sections at 0.2-μm intervals was captured and deconvolved. The z-stack was maximum projected, and the integrated intensity in a 6 × 6 or 8 × 8 pixel square around the SPB was recorded. A cellular background intensity was recorded for each cell and subtracted from the SPB intensity. Only SPBs with the brightest pixel between sections 3–13 were used.

The variability of SPB intensities within a time point is not an artifact of GFP bleaching because the SPB intensity does not correlate to the position of the SPB in the z-stack and the total amount of bleaching during the image acquisition is ∼10% (our unpublished data).

Noise in the quantification protocol was evaluated by imaging latex beads. TetraSpeck microspheres (100 nm; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) were each imaged twice as described for SPBs. The fluorescence intensity of the beads was measured as described, and the percentage difference between the first and second image was calculated, N = 101, for two separate experiments: %difference = |100 × (intensity 1–intensity 2)/intensity1|. The mean variability was 5 ± 3.5%. Because the SPBs vary in intensity by ∼25%, most of the variation is due to a biological difference.

Fluorescence Recovery after Photobleaching (FRAP) Experiments

FRAP and fluorescence intensity analysis was performed as described previously (Maddox et al., 2000), except a Hamamatsu Photonics (Bridgewater, NJ) Orca ER camera C4742-95 was used, and Spc110p-GFP SPBs instead of GFP-Tub1p microtubules were photobleached. All FRAP experiments were carried out at room temperature (22–25°C). For the telophase FRAP experiments, the z-series consisted of nine frames (350-ms exposures) at 0.3-μm intervals directly before and after photobleaching and 13 frames (350-ms exposures) at 0.2-μm intervals in the next cell cycle. For the G2 FRAP experiments, the z-series consisted of nine frames (350-ms exposures) at 0.3-μm intervals directly before and after photobleaching and 12 frames (350-ms exposures) at 0.2-μm intervals 30 min later. Cells were observed to divide three times subsequent to photobleaching, indicating that photobleaching the SPB did not impair cell cycle progression.

RESULTS

Quantification of Fluorescence at the SPB

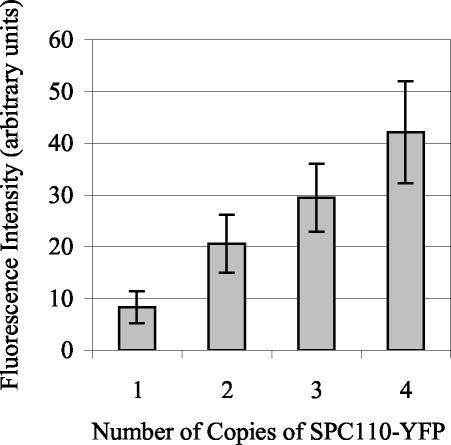

The study of the assembly of Spc110p into the spindle pole body requires the ability to quantify GFP- and YFP-tagged SPB structural components. We first tested whether the YFP fluorescence at the SPB was proportional to the relative amount of YFP-tagged protein present. To this end, we constructed a series of four tetraploid strains that had one, two, three, or four copies of SPC110 tagged with YFP. The remaining copies of SPC110 were tagged with CFP, so that all four copies of SPC110 were tagged. The average YFP fluorescence at the SPB was proportional to the number of copies of SPC110-YFP (Figure 1). Thus, fluorescence is proportional to the levels of the protein at the SPB, and the relative levels of protein can be compared from one population to another.

Figure 1.

Fluorescence intensity quantification of Spc110p-YFP at the SPB in tetraploid strains. Tetraploid strains (TYY98-101) carrying one, two, three, or four copies of SPC110-YFP were analyzed. The average YFP fluorescence at the SPB was proportional to the number of copies of SPC110-YFP. The total YFP fluorescence at the SPB was determined, as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS, in cells with preanaphase spindles (N = 47–106 for each genotype). Means reported ± SD.

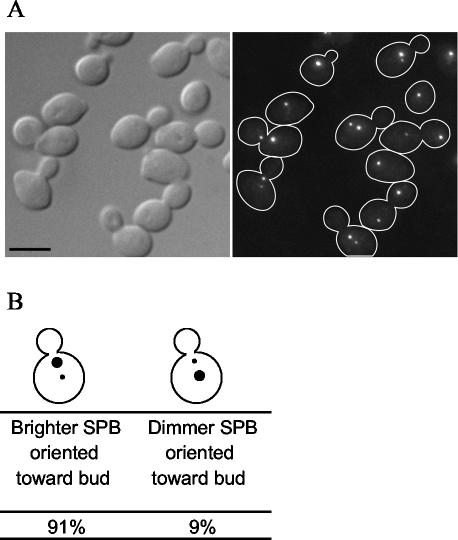

The study of assembly also requires a method to distinguish the old SPB from the new SPB in each cell. Pereira et al. (2001) exploited the slow development of fluorescence in RFP to demonstrate that the SPB containing old Spc42p-RFP segregates to the bud. This SPB is the brightest because it contains the older Spc42p-RFP, which has had enough time for the fluorescence to develop. We repeated these experiments by using Spc110p-RFP to determine whether the nuclear side of the SPB behaved similarly to the crystalline layer. We found that in 91% of cells expressing Spc110p-RFP, the SPB closest to the bud neck is brighter than the SPB away from the neck (Figure 2). Therefore, we identified the SPB closest to the bud neck as the old SPB.

Figure 2.

Slow-folding RFP predominantly labels one of the two SPBs of an Spc110p-RFP cell. (A) Spc110p was tagged at the C terminus with RFP (TYY115-2D). Cells from an exponentially growing culture were fixed and imaged as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. Bar, 5 μm. (B) The cellular position of the more brightly labeled SPB with respect to the bud neck was recorded in >200 cells.

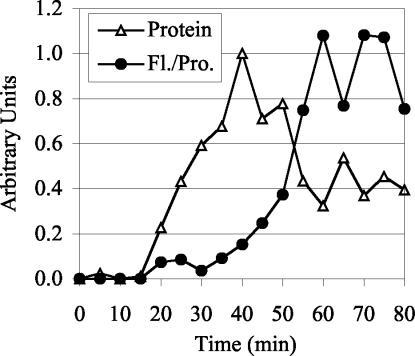

We found that the rate of formation of the GFP chromophore is sufficiently fast in vivo that it is unlikely to affect the interpretation of our quantitative time courses. The t1/2 of Spc110p-GFP fluorescence maturation in vivo is only 10 min (Figure 3). A significant portion of the pool of Spc110p-GFP available for assembly during the cell cycle will be mature at all times for two reasons. First, the t1/2 of chromophore formation is short compared with the 90-min cell cycle. Second, about half of the Spc110p in the cell is in a free nuclear pool, and Spc110p protein levels only rise twofold during the cell cycle (Friedman et al., 1996; our unpublished data). Accordingly, unlike the slow-folding RFP, the fluorescence of the old and the new SPB labeled with Spc110p-GFP is similar (see below).

Figure 3.

Fluorescence intensity quantification and protein quantification of Spc110p-GFP during an induction time course. Spc110p-GFP in strain CRY1+pTY39 (GAL-SPC110-GFP) was induced by addition of galactose (4%) and after a 40-min induction, cycloheximide (0.5 mg/ml) and glucose (2%) were added to inhibit further protein synthesis. The experiment was performed twice with similar results. For each experiment the average nuclear fluorescence (subtracted for background cellular fluorescence) of >100 cells per time point was measured and normalized to the average intensity from 55 to 75 min. The Spc110p-GFP protein levels detected by Western blot analysis were averaged and normalized to the 40-min time point. The normalized data sets were then averaged to yield the data presented.

SPB Core Cell Cycle Growth and Reduction

To determine whether the relative amount of Spc110p at the SPB varies during the cell cycle, we quantified the amount of Spc110p-GFP in SPBs in a synchronous population of cells isolated by elutriation (Figure 4A). The amount of Spc110p-GFP increased at the end of G1, reflecting the incorporation of Spc110p-GFP into the new SPB. After duplication, SPBs are connected in the side-by-side configuration and appear as a single spot with almost twice the amount of Spc110p as an unduplicated G1 SPB (60 min). After separation, each SPB has the same amount of Spc110p-GFP as a G1 SPB. SPBs grow up to 20% at the later G2 time point (80 min). In cells with long spindles, the SPBs have 40% more Spc110p-GFP than the G1 SPBs, indicating that the SPBs also grow during anaphase.

Figure 4.

Fluorescence intensity quantification of Spc110p-GFP at the SPB during the course of the cell cycle. The levels of Spc110p at the SPB vary during the cell cycle. (A) A G1 population of diploid Spc110p-GFP (TYY113) cells was isolated by centrifugal elutriation. Samples were collected at regular intervals after release into YPD medium at 30°C, and the total GFP fluorescence intensity at the SPB was determined. For cells with two SPBs, each SPB was quantified separately. The mean intensity ± SD of 14–68 SPBs is shown for each time point. The cartoons indicate cell cycle progression. Cells were staged by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of DNA content, budding, and SPB separation (our unpublished data). The experiment was carried out independently two times with similar results, only one of which is shown. (B) The GFP fluorescence intensity at the SPB was determined in a haploid Spc110p-GFP (TYY85-3D) strain at regular intervals after release from α-factor arrest (see MATERIALS AND METHODS). Time is in minutes after release from α-factor arrest. The mean intensity ± SD of 24–67 SPBs is shown for each time point. The cartoons indicate cell cycle progression. Cells were staged by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of DNA content, budding, and SPB separation (our unpublished data). The experiment was carried out independently four times. (C) Ratio of fluorescence of the old SPB/fluorescence of the new SPB in Spc110p-GFP diploid (TYY113) cells with short spindles. The SPB closest to the bud neck was designated the old SPB. The average ratio (± SD) was 1.1 ± 0.4.

Cells released from α-factor arrest show a different profile of Spc110p-GFP levels at the SPB (Figure 4B). The SPBs in α-factor-treated cells have 60% as much Spc110p-GFP as SPBs in untreated G1 cells (see below). After cells are released from α-factor, the majority of incorporation occurs by the time of bud emergence, with a slight increase during G2 and mitosis. Thus, by the time of SPB separation (40 min) the SPBs have incorporated 70% more Spc110p-GFP and are almost the normal size for a G2 SPB. By the beginning of the next cell cycle (90 min), the SPBs are the size of G1 SPBs from an untreated culture.

In the experiment using elutriated cells, we observed addition of Spc110p to the SPB but did not see return to the initial levels in the second G1 (110 min; Figure 4A). However, this might be explained by the loss of synchrony that occurs during the transition to the next cell cycle, because mother cells enter the next cell cycle before daughter cells. We reasoned that if Spc110p was added to the old SPB but was not removed, the old SPB would tend to have more Spc110p than the new SPB. Instead, the amount of Spc110p-GFP in the old SPB was almost equal to the amount of Spc110p-GFP in the new SPB (Figure 4C), indicating that loss of components during G1 contributes to SPB size regulation.

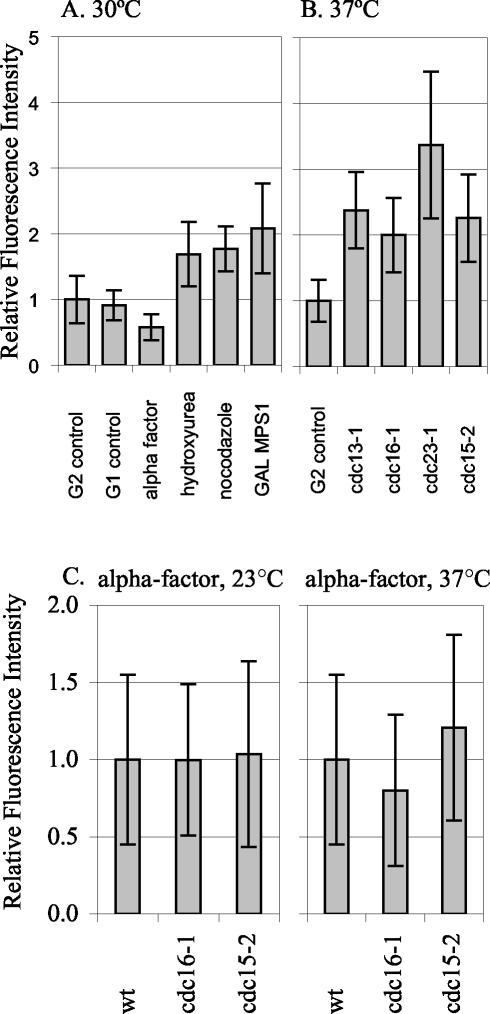

Spc110p Is Incorporated into the SPB during Cell Cycle Arrests in G2/M

We tested whether SPB growth occurs in response to different cell cycle arrests, perhaps representing some type of repair mechanism (Figure 5, A and B). We tested a variety of conditions that induce arrest in G1, G2/M, or telophase. Nocodazole and GAL-MPS1 overexpression activate the mitotic checkpoint. Hydroxyurea activates the DNA replication checkpoint. At all three arrests, SPBs had ∼twofold more Spc110p-YFP than the G2 control grown at 30°C. SPBs were also examined in cells arrested using four different temperature-sensitive mutations. The cdc13-1 mutation leads to unreplicated DNA at the telomeres, and cells arrest at the DNA damage checkpoint with short spindles (Garvik et al., 1995). Cdc16p and Cdc23p are both components of the anaphase promoting complex; at the restrictive temperature, cdc16-1 and cdc23-1 cells are unable to proceed through mitosis and arrest at the short spindle stage (Irniger et al., 1995; King et al., 1995; Zachariae and Nasmyth, 1996; Wasch and Cross, 2002). The cdc15-2 mutation causes cells to arrest in anaphase before exit from mitosis (Jaspersen et al., 1998). The temperature-sensitive–arrested strains each had an average of two- to threefold more Spc110p-YFP at the SPB than control cells grown at 37°C. Thus, Spc110p is added to the SPB during a variety of G2/M arrests. In contrast, cells arrested by α-factor before SPB duplication, have only 60% of the Spc110p at the SPB than in G1 control SPBs.

Figure 5.

Spc110p-YFP at the SPB during different cell cycle arrests. The relative amount of Spc110p-YFP at the SPB in control and arrested cells was quantified. (A) Arrests at 30°C. G2 control: SPBs from TYY80-5A cells in G2 with separated SPBs and short spindles were quantified. The mean intensity of the 30°C G2 control, was set as 1.0. G1 control: SPBs from unbudded TYY80-5A cells with a single SPB spot were quantified. α-Factor: strain TYY80-5A was arrested in α-factor (see MATERIALS AND METHODS). The measurement of Spc110p at the SPBs in cells treated with α-factor was performed eight times in three different strains. A representative experiment is shown. Hydroxyurea: strain DHY15 was grown to early logarithmic phase in YPD and arrested by adding hydroxyurea to a final concentration of 0.1 M, cells were collected after 180 min. Fluorescence intensity in hydroxyurea is shown relative to DHY15 G2 control. Nocodazole: strain TYY80-5A was grown to early logarithmic phase in YPD and arrested by adding nocodazole to a final concentration of 15 μg/ml, cells were collected after 140 min. Because nocodazole collapses the spindle, the two SPBs appeared as a single spot, and the total intensity was divided by 2 to get the average intensity per SPB. GAL MPS1: strain TYY102-5D was grown in YPR and arrested by adding 2% galactose to an early logarithmic phase culture, cells were collected after 195 min. (B) Arrests at 37°C. G2 control: strain TYY80-5A was grown at 37°C and SPBs from cells in G2 with separated SPBs and short spindles were quantified. The mean intensity of the 37°C G2 control was set as 1.0. cdc13-1, cdc16-1, cdc23-1, and cdc15-2: strains TYY92-18B, TYY93-16D, TYY110, and TYY109, respectively, were arrested at the nonpermissive temperature (37°C) for 195 min. (Although four of the strains contain MET3-SPC110-YFP, it was not induced for these experiments. Instead all strains were grown in YPD [or YPR] medium supplemented with 300 μg/ml methionine to repress MET3 SPC110-YFP.) (C) Temperature shifts in G1. Wild-type, cdc16-1, and cdc15-2 cultures were arrested in G1 with α-factor at 23°C. After 1.5 generations, the culture was filtered and resuspended in media with fresh α-factor and shifted to 37°C for 90 min. Under these conditions the arrest was maintained, as monitored by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis.

The growth during G2/M arrests could either be due to cell cycle state or to the specific mutations causing the G2/M arrest. To distinguish between these possibilities, we arrested temperature-sensitive mutants in G1 (α-factor) at the permissive temperature and then maintained the G1 arrest while shifting to the nonpermissive temperature (Figure 5C). SPBs from cdc16-1 and cdc15-2 cells had about the same amount of Spc110p-YFP as wild-type controls arrested in G1 at both the permissive and the nonpermissive temperature. Therefore, the regulatory mechanisms that control SPB core size are sensitive to cell cycle state.

Spc110p Exchanges during G1/S

We used FRAP analysis of SPC110-GFP cells to measure exchange of Spc110p. One SPB was photobleached in large-budded telophase cells. Fluorescence recovery was measured in the following G2 by which time the SPBs had duplicated and separated, giving one old SPB that had been bleached and one newly made SPB (Figure 6, A–C). Recovery of the bleached SPB was 47 ± 15% (Figure 6D) compared with the new SPB1 and 58 ± 30% compared with itself before bleaching.2 Because SPBs do not incorporate additional Spc110p between telophase and the following G2 phase (Figure 4A), the appearance of unbleached Spc110p-GFP in the bleached SPB must be due to replacement of the bleached molecules by unbleached molecules (exchange) rather than incorporation of additional Spc110p-GFP molecules (growth). Thus, we conclude that 50% of the old Spc110p exchanges for new Spc110p in the old SPB between telophase and the following G2.

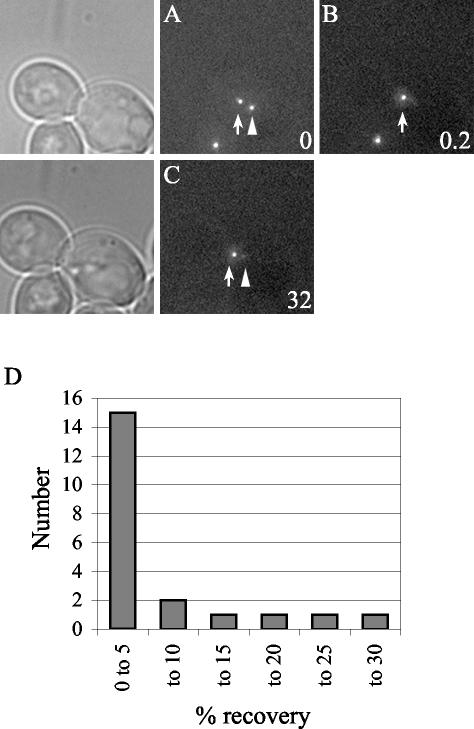

Figure 6.

FRAP analysis of an Spc110p-GFP diploid strain (TYY113) reveals exchange in G1/S. The SPB in the mother cell body of a cell in telophase was photobleached (N = 20) and fluorescence intensity followed in the next cell cycle. (A) Image of a representative cell before photobleaching. (B) The same cell as in A immediately after photobleaching. Arrow indicates photobleached SPB. (C) Cell cycle progression was monitored by transmitted light until the new bud was about one-third of the diameter of the mother cell and a final z-series was acquired in the fluorescence channel. The average interval between photobleaching and the following G2 was 74 min. Time is in minutes. Bar, 2 μm. (D) Percentage of recovery of fluorescence at the bleached SPB. The average percent recovery is 47 ± 15%. Because it was not possible to determine which SPB was destined to the bud in 6 of the 20 cells, in this experiment we assumed that the bleached SPB is dimmer than the new SPB.

To study the incorporation of newly synthesized Spc110p into the old SPB by an alternative method, we constructed a strain that has inducible Spc110p-YFP. In this strain, SPC110-YFP is under the control of the MET3 promoter and a pulse of new Spc110p-YFP can be made by removal of methionine from the medium. The normal genomic locus of SPC110 is tagged with CFP; Spc110p-CFP is always present and marks the SPBs. We developed a method to induce only modest levels of Spc110p-YFP. (The amount of Spc110p-YFP induced was measured in a parallel experiment by using a strain MET3-SPC110-YFP, SPC110-YFP. On average, induced cells contained 22% more Spc110p-YFP (p = 8 × 10–8, by Student's t test) at the SPB than uninduced cells [Figure 7A]). We followed incorporation of newly induced Spc110p-YFP after release from G1 arrest and found that it incorporated into both SPBs by the time of SPB separation (Figure 7B). The observed ratio of 1.06 of Spc110p-YFP in the old SPB/Spc110p-YFP in the new SPB indicates that both SPBs incorporate about the same amount of new Spc110p-YFP (Figure 7C). The extent of incorporation of new Spc110p-YFP into the old SPB could not be accounted for by the growth that occurs in G2 after release from α-factor arrest. Therefore, consistent with the telophase FRAP results, the induction method also showed that Spc110p molecules in the old SPB are exchanged for new Spc110p molecules.

Figure 7.

Newly induced Spc110p-YFP incorporates into both the new and the old SPB, consistent with exchange during G1/S. (A) Quantification of the amount of “extra” Spc110p at the SPB due to induction. SPC110-YFP, MET3 SPC110-YFP cells (TYY80-5A) were grown in SD-met+met and arrested with α-factor (see MATERIALS AND METHODS). Half of the culture was induced by removal of methionine, whereas the other half was instead washed with SD-met+met and incubated for 90 min further in the continued presence of α-factor. Both cultures were then washed with SD-met+met and released into the cell cycle in SD-met+met. The fluorescence intensity of YFP at the SPBs in induced and uninduced cells that had separated their SPBs was compared. N = 47 and 70 for uninduced and induced, respectively. Bars represent the means. (B) An SPC110-CFP, MET3 SPC110-YFP (TYY69-2A) culture was subject to a 90-min pulse of induction of Spc110p-YFP (see MATERIALS AND METHODS). Images in the CFP and YFP channels were captured at regular intervals. Time is indicated in min after release: 0–10 min (G1), cells are unbudded; 30 min (S phase), SPBs are duplicated but not yet separated; 40–60 min (G2), cells are budded and SPBs have separated; 70 min, anaphase. Bar, 5 μm. (C) YFP fluorescence intensity of both SPBs was measured (see MATERIALS AND METHODS) in cells 40, 50, and 60 min after release from α-factor arrest for the experiment shown in B. The average ratio of YFP fluorescence intensity at the old SPB/YFP fluorescence intensity at the new SPB, determined for each cell (N = 37–41), was 1.06 ± 0.25. The SPB closest to the bud neck was designated the old SPB. Time is in min after release from α-factor arrest. Bars represent means.

Spc110p-GFP at the SPB Does Not Exchange during G2

We used FRAP to measure the exchange of Spc110p at the SPB in G2. Cells in G2 were identified as those with a medium bud and a short (preanaphase) spindle. For each experiment Spc110p-GFP in one of the two separated SPBs was photobleached (see MATERIALS AND METHODS) and the cell was imaged after 30 min (Figure 8, A–C). Only the data from cells that did not elongate their spindles during the 30-min interval is included. Fifteen of 21 cells had <5% fluorescence recovery at the bleached SPB. Only three cells had as much as 20–27% recovery (Figure 8D). Thus, the recovery during G2 was substantially less than the recovery that occurred between telophase and G2 and probably represents the small amount of growth that occurs in late G2 (Figure 4A) and not exchange. Therefore, the G2 SPB is stable relative to the SPB during the earlier part of the cell cycle.

Figure 8.

FRAP analysis of Spc110p-GFP diploid cells (TYY113) in G2 with short spindles. Little Spc110p is exchanged in G2. One SPB (arrowhead) in a G2 cell was photobleached, N = 22. (A) Image of a representative cell before photobleaching. (B) The same cell as in A immediately after photobleaching. (C) A final z-series was acquired in the fluorescence channel after ∼30 min. Time is in minutes. Bar, 2 μm. (D) Histogram plot of the percentage of recovery.

DISCUSSION

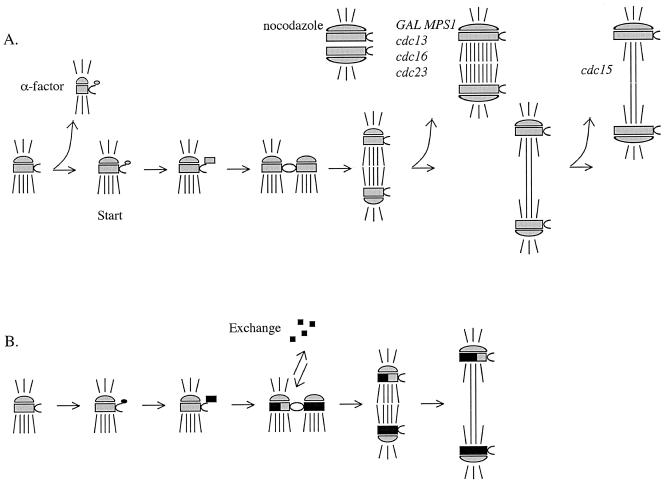

The SPB core grows during late G2 and M, shrinks during early G1 and exchanges Spc110p during G1/S. The SPB incorporates additional Spc110p during cell-cycle arrests in G2 and M phases and the growth does not depend on microtubules. Taking these observations into account, we can build a model of the SPB life cycle (Figure 9). In G1/S the SPB duplicates, and both the old and new structures are open to assembly and exchange of components. In G2, the SPB structure does not exchange. Late in the cell cycle the SPB grows and then shrinks again early in the next G1. The response to α-factor includes removal of Spc110p from the SPB. During arrests in G2/M phase, the SPB core is competent to assemble more components.

Figure 9.

Model of the SPB life cycle. The SPBs are depicted with shorter cytoplasmic microtubules and longer nuclear microtubules. The satellite forms at the distal tip of the half-bridge in G1. The satellite enlarges to form the duplication plaque. In G1/S, the SPBs duplicate and are tethered in the side-by-side configuration. In G2, the bridge cleaves and the SPBs move apart to form a short spindle. In anaphase, the spindle elongates. (A) SPB core growth during the cell cycle. The SPB core shrinks during α-factor treatment. The SPB core grows in nocodazole, GAL-MPS1 overexpression, and cdc13, cdc16, cdc23, and cdc15 arrests. In an unperturbed cell cycle, the SPB core grows late in the cell cycle. (B) Exchange of components during the cell cycle. The old SPB exchanges ∼50% of the old components in G1/S. Old components are gray, new components are black.

SPB Core Growth

The relative amount of Spc110p at the SPB correlates well with the relative size of the SPB core measured from electron micrographs. We found about half the Spc110p at the SPB in cells treated with α-factor compared with untreated cells, and Byers and Goetsch, 1974 measured the SPBs in α-factor–treated cells to be one-half the size of those in asynchronous cells. Furthermore, because overexpression of Mps1p leads to activation of the mitotic checkpoint (Hardwick et al., 1996), a state with low Cdc20p activity, 2.1-fold more Spc110p-YFP at the SPB during the GAL-MPS1 arrest is consistent with electron micrograph measurements showing that SPBs are ∼2.3 times larger at the cdc20-1 arrest (O'Toole et al., 1997). Thus, the amount of Spc110p at the SPB is a measure of the size of the core structure.

We found that growth and shrinkage of the core SPB are regulated in the cell cycle. Findings by Bullitt et al., (1997) are consistent with cell cycle regulation of SPB size: two predominant size classes of SPBs were observed in their purified SPB preparations. SPBs in Schizosaccharomyces pombe also grow but start out large in G1. After duplication, the new SPBs are small and equal in diameter but quickly grow to full size (Ding et al., 1997). A growth phase seems to be a conserved part of the SPB life cycle in S. cerevisiae and S. pombe.

The ability of the SPB to grow may be controlled by the activity of mitotic cyclins Clb1p and Clb2p. Clb1p and Clb2p activity becomes dominant in late G2 (Lew, 1997). Similarly, our analysis of synchronized cultures and our G2 FRAP experiments indicate that SPBs transition from a stable state in early G2 to a growing state in late G2. In synchronized cultures, no SPB growth was observed at the beginning of G2. In the FRAP experiments, the majority of G2 SPBs exhibited little or no exchange. However, at the end of G2, the SPBs grew and this growth likely accounts for the small fraction of SPBs that exhibited ∼20% recovery of fluorescence in the G2 FRAP experiments. SPBs also grew during all G2 and M arrests tested, including an arrest at the DNA damage checkpoint, at the mitotic checkpoint, and in telophase. This diverse collection of arrests all shares the common feature of high levels of Clb2p. In contrast, SPBs shrank after telophase and during an α-factor arrest, a time when Clb2p-Cdc28p activity is low.

Spc110p Exchange

We found that ∼50% of the old Spc110p molecules in the old SPB were exchanged during G1/S but that the structure was stable in G2. The old Spc110p that comes from the old SPB could be either degraded or introduced into the new pole. The difference in exchange between G1/S and G2 suggests that the exchange process must be regulated so that it readily occurs during SPB duplication and is turned off once both SPBs are assembled.

Two lines of evidence indicate that the fluorescence recovery we observed at the bleached SPB was due to dynamic rearrangement of Spc110p-GFP molecules rather than to return of fluorescence to individual bleached GFP molecules. First, although GFP molecules can show reversible photobleaching, this process occurs very rapidly, on the order of a few milliseconds (Swaminathan et al., 1997), and thus would be finished even before the postbleach image is acquired in our experiments. Second, two different experiments have shown that fluorescence recovery depends on the active metabolism of the cell. The dynamic turnover of FtsZ cytoskeletal molecules in the Z-ring in bacteria was not observed when cells were treated with paraformaldehyde before photobleaching (Stricker et al., 2002). Yeast cells treated with azide to deplete ATP showed no recovery of GFP-tubulin in photobleached spindles (Pearson, unpublished data).

Pereira et al. (2001) investigated the assembly of the core component Spc42p by photobleaching the old SPB in G1. After SPB duplication and separation, the old SPB was less brightly labeled with Spc42p-GFP than the new SPB, similar to what we found when studying Spc110p. The extent of Spc42p exchange is not known.

A deeper appreciation of the exchange of SPB components can be gained by comparing it to subunit exchange in other cellular structures. In higher eukaryotes, the centrosomal component γ-tubulin recovers 50% in 60 min in both interphase and mitosis (Khodjakov and Rieder, 1999), indicating that a portion of centrosomal γ-tubulin did not exchange. The γ-tubulin pool that exchanges is more dynamic than Spc110p because it exchanges more rapidly (relative to the length of the cell cycle) and can exchange throughout the cell cycle. In yeast γ-tubulin may also be exchanged at the SPB; cell fusion experiments revealed that SPBs from cells not expressing Tub4p-GFP became labeled upon fusion to cells expressing Tub4p-GFP (Marschall et al., 1996). Spindle microtubules in yeast are much more dynamic than Spc110p, with an average half-time of recovery of 52 s (Maddox et al., 2000). Yeast spindle components Cin8p and Ase1p have recovery half-times of 28 ± 7 s and ∼7.5 min, respectively (Schuyler et al., 2003). In higher eukaryotic cells, Mad2p and Cdc20p transiently associate with the kinetochore, with average half-time of recovery of 28 and 5.1 s, respectively (Howell et al., 2000; Kallio et al., 2002). Thus far, the SPB has many dynamic properties but is still more stable than other components examined. Subunit exchange in other budding yeast mitotic structures such as the core kinetochore and cohesin complexes have not yet been reported.

Spindle Asymmetries

The SPB is dynamic, but not all of the Spc110p at the SPB is turned over in the course of one cell cycle, enabling the new and the old SPB to be differentiated. The old SPB is segregated to the bud and the new SPB to the mother cell. The fact that the old SPB contains less new material than the new SPB can explain the phenotype of many temperature-sensitive mutants in structural and regulatory SPB components. These mutants often contain one apparently normal SPB and one defective or missing SPB, as expected, if during assembly at the nonpermissive temperature, the new SPB components are not evenly dispersed. This asymmetric SPB mutant phenotype has been observed in spc110, spc42, spc29, mps1, msp2, ndc1, and cdc37 mutants (Winey et al., 1991; Donaldson and Kilmartin, 1996; Sundberg and Davis, 1997; Schutz and Winey, 1998; Adams and Kilmartin, 1999; Elliott et al., 1999). Also, several proteins localize asymmetrically on the cytoplasmic portion of the spindle. Tem1p, Bub2p, Bfa1p, and Cdc15p preferentially associate with one of the two SPB outer faces during mitosis (Cenamor et al., 1999; Bardin et al., 2000; Pereira et al., 2000; Xu et al., 2000; Menssen et al., 2001; Pereira et al., 2001). It is not known whether asymmetries in the spindle are established by the difference between the old and new SPBs or by an independent mechanism such as differential contact with the polarized cell cortex.

Spindle asymmetry in the nucleus has also been reported. In ipl1, sli15, and spc34 mutants, the chromosomes fail to biorient and are preferentially attached to the old SPB (Janke et al., 2002; Tanaka et al., 2002). Kinetochore microtubules in S. cerevisiae and other fungi remain attached to the kinetochores during all phases of the cell cycle (Heath, 1980; O'Toole et al., 1999). The mechanism for achieving biorientation of sister chromatids is not known, but several lines of evidence suggest that the chromatids are actively rearranged by the time of sister separation. First, replicatively older chromatids are randomly distributed between mother and daughter upon division (Neff and Burke, 1991). Second, cdc6 mutants, which fail to replicate DNA, distribute their chromosomes between the two SPBs (Piatti et al., 1995; Stern and Murray, 2001). The rearrangement of chromatids could be achieved by breaking the attachment at one or more of four possible interfaces: the microtubule-kinetochore interface, the microtubule-SPB interface, the γ-tubulin complex-Spc110p interface, and the Spc110p-SPB interface. Exchange of Spc110p during duplication could be a mechanism for dispersing the kinetochores randomly between the two SPBs.

A New Paradigm

The combination of quantifying levels of proteins during the cell cycle and live-cell quantitative FRAP analysis was a powerful way to investigate assembly of the SPB. We found several dynamic aspects of assembly: growth, shrinkage, and exchange. These dynamic characteristics were not compatible with the conservative-dispersive model of duplication, which assumes that the duplicated entities are static. Instead, we found that assembly and duplication could be well characterized by examining exchange and growth. This methodology could be applied to other inherited structures in the cell to discern universal and unique properties of the assembly of macromolecular structures.

CONCLUSIONS

We find that Spc110p is very dynamic. This dynamic behavior may be integral to the dynamic process of building a mitotic spindle and provides a mechanism to respond to changes in cellular conditions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Benjamin Glick, Dale Hailey, David Morgan, Mike Moser, and Harry Mountain for reagents, and Paul Maddox for help with FRAP. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants GM-40506 (to T.N.D. and T.J.Y.) and GM-32238 (to K.B. and C.G.P.), and a National Science Foundation predoctoral fellowship (to T.J.Y.).

Abbreviations used: CFP, cyan fluorescent protein; FRAP, fluorescence recovery after photobleaching; GFP, green fluorescent protein; RFP, red fluorescent protein; SPB, spindle pole body; YFP, yellow fluorescent protein.

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E02-10-0655. Article and publication date are available at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E02-10-0655.

Footnotes

Percent recovery = 100 × (F[bleached G2]/F[new G2]), where F(bleached G2) is the fluorescence intensity of the bleached SPB in the next G2, and F(new G2) is the fluorescence intensity of the new SPB in G2. Since the two SPBs in G2 contain on average the same amount of Spc 100p (Fig. 4A), the fluorescence of the bleached SPB relative to the new SPB gives an estimate of the fraction of bleached molecules that have been replaced by new unbleached molecules.

Percent recovery = 100 × ([F(bleached G2]–F[postbleach])/(F[prebleach]–F[postbleach]), where F(bleached G2) is the fluorescence intensity of the bleached SPB in the next G2, F(postbleach) is the fluorescence intensity of the SPB immediately following photobleaching, and F(prebleach) is the fluorescence intensity of the SPB immediately preceding photobleaching.

References

- Adams, I.R., and Kilmartin, J.V. (1999). Localization of core spindle pole body (SPB) components during SPB duplication in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 145, 809–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardin, A.J., Visintin, R., and Amon, A. (2000). A mechanism for coupling exit from mitosis to partitioning of the nucleus. Cell 102, 21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevis, B.J., and Glick, B.S. (2002). Rapidly maturing variants of the Discosoma red fluorescent protein (DsRed). Nat. Biotechnol. 20, 83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullitt, E., Rout, M.P., Kilmartin, J.V., and Akey, C.W. (1997). The yeast spindle pole body is assembled around a central crystal of Spc42p. Cell 89, 1077–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers, B., and Goetsch, L. (1974). Duplication of spindle plaques and integration of the yeast cell cycle. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 38, 123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers, B., and Goetsch, L. (1975). Behavior of spindles and spindle plaques in the cell cycle and conjugation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 124, 511–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenamor, R., Jimenez, J., Cid, V.J., Nombela, C., and Sanchez, M. (1999). The budding yeast Cdc15 localizes to the spindle pole body in a cell-cycle-dependent manner. Mol. Cell. Biol. Res. Commun 2, 178–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, T.N. (1992). A temperature-sensitive calmodulin mutant loses viability during mitosis. J. Cell Biol. 118, 607–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding, R., West, R.R., Morphew, D.M., Oakley, B.R., and McIntosh, J.R. (1997). The spindle pole body of Schizosaccharomyces pombe enters and leaves the nuclear envelope as the cell cycle proceeds. Mol. Biol. Cell 8, 1461–1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, A.D., and Kilmartin, J.V. (1996). Spc42p: a phosphorylated component of the S. cerevisiae spindle pole body (SPD) with an essential function during SPB duplication. J. Cell Biol. 132, 887–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, S., Knop, M., Schlenstedt, G., and Schiebel, E. (1999). Spc29p is a component of the Spc110p subcomplex and is essential for spindle pole body duplication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 6205–6210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, D.B., Sundberg, H.A., Huang, E.Y., and Davis, T.N. (1996). The 110-kD spindle pole body component of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a phosphoprotein that is modified in a cell cycle-dependent manner. J. Cell Biol. 132, 903–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvik, B., Carson, M., and Hartwell, L. (1995). Single-stranded DNA arising at telomeres in cdc13 mutants may constitute a specific signal for the RAD9 checkpoint. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 6128–6138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiser, J.R., van-Tuinen, D., Brockerhoff, S.E., Neff, M.M., and Davis, T.N. (1991). Can calmodulin function without binding calcium? Cell 65, 949–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardwick, K.G., Weiss, E., Luca, F.C., Winey, M., and Murray, A.W. (1996). Activation of the budding yeast spindle assembly checkpoint without mitotic spindle disruption. Science 273, 953–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath, I.B. (1980). Behavior of kinetochores during mitosis in the fungus Saprolegnia ferax. J. Cell Biol. 84, 531–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell, B.J., Hoffman, D.B., Fang, G., Murray, A.W., and Salmon, E.D. (2000). Visualization of Mad2 dynamics at kinetochores, along spindle fibers, and at spindle poles in living cells. J. Cell Biol. 150, 1233–1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irniger, S., Piatti, S., Michaelis, C., and Nasmyth, K. (1995). Genes involved in sister chromatid separation are needed for B-type cyclin proteolysis in budding yeast. Cell 81, 269–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janke, C., Ortiz, J., Tanaka, T.U., Lechner, J., and Schiebel, E. (2002). Four new subunits of the Dam1-Duo1 complex reveal novel functions in sister kinetochore biorientation. EMBO J. 21, 181–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaspersen, S.L., Charles, J.F., Tinker-Kulberg, R.L., and Morgan, D.O. (1998). A late mitotic regulatory network controlling cyclin destruction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 9, 2803–2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallio, M.J., Beardmore, V.A., Weinstein, J., and Gorbsky, G.J. (2002). Rapid microtubule-independent dynamics of Cdc20 at kinetochores and centrosomes in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 158, 841–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodjakov, A., and Rieder, C.L. (1999). The sudden recruitment of gamma-tubulin to the centrosome at the onset of mitosis and its dynamic exchange throughout the cell cycle, do not require microtubules. J. Cell Biol. 146, 585–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilmartin, J.V., Dyos, S.L., Kershaw, D., and Finch, J.T. (1993). A spacer protein in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae spindle poly body whose transcript is cell cycle-regulated. J. Cell Biol. 123, 1175–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, R.W., Peters, J.M., Tugendreich, S., Rolfe, M., Hieter, P., and Kirschner, M.W. (1995). A 20S complex containing CDC27 and CDC16 catalyzes the mitosis-specific conjugation of ubiquitin to cyclin B. Cell 81, 279–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanski, R.S., and Borisy, G.G. (1990). Mode of centriole duplication and distribution. J. Cell Biol. 110, 1599–1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lew, D.J., Weinert, T., and Pringle, J.R. (1997). Cell cycle control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In: The Molecular and Cellular Biology of the Yeast Saccharomyces, vol. 3, ed. J.R. Pringle, J.R. Broach, and E.W. Jones, Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 607–696. [Google Scholar]

- Maddox, P.S., Bloom, K.S., and Salmon, E.D. (2000). The polarity and dynamics of microtubule assembly in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 36–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marschall, L.G., Jeng, R.L., Mulholland, J., and Stearns, T. (1996). Analysis of Tub4p, a yeast gamma-tubulin-like protein: implications for microtubule-organizing center function. J. Cell Biol. 134, 443–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathias, N., Johnson, S.L., Winey, M., Adams, A.E., Goetsch, L., Pringle, J.R., Byers, B., and Goebl, M.G. (1996). Cdc53p acts in concert with Cdc4p and Cdc34p to control the G1-to-S-phase transition and identifies a conserved family of proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 6634–6643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, V.W., and Aguilera, A. (1990). High levels of chromosome instability in polyploids of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutat. Res. 231, 177–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menssen, R., Neutzner, A., and Seufert, W. (2001). Asymmetric spindle pole localization of yeast Cdc15 kinase links mitotic exit and cytokinesis. Curr. Biol. 11, 345–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff, M.W., and Burke, D.J. (1991). Random segregation of chromatids at mitosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 127, 463–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Toole, E.T., Mastronarde, D.N., Giddings, T.H., Jr., Winey, M., Burke, D.J., and McIntosh, J.R. (1997). Three-dimensional analysis and ultrastructural design of mitotic spindles from the cdc20 mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 8, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Toole, E.T., Winey, M., and McIntosh, J.R. (1999). High-voltage electron tomography of spindle pole bodies and early mitotic spindles in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 2017–2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, G., Hofken, T., Grindlay, J., Manson, C., and Schiebel, E. (2000). The Bub2p spindle checkpoint links nuclear migration with mitotic exit. Mol. Cell 6, 1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, G., Tanaka, T.U., Nasmyth, K., and Schiebel, E. (2001). Modes of spindle pole body inheritance and segregation of the Bfa1p-Bub2p checkpoint protein complex. EMBO J. 20, 6359–6370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piatti, S., Lengauer, C., and Nasmyth, K. (1995). Cdc6 is an unstable protein whose de novo synthesis in G1 is important for the onset of S phase and for preventing a `reductional' anaphase in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 14, 3788–3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutz, A.R., and Winey, M. (1998). New alleles of the yeast MPS1 gene reveal multiple requirements in spindle pole body duplication. Mol. Biol. Cell 9, 759–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuyler, S.C., Liu, J.Y., and Pellman, D. (2003). The molecular function of Ase1p: evidence for a MAP-dependent midzone-specific spindle matrix. J. Cell Biol. 160, 517–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, F., Fink, G.R., and Hicks, J.B. (1986). Methods in Yeast Genetics, Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

- Sikorski, R.S., and Hieter, P. (1989). A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122, 19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern, B.M., and Murray, A.W. (2001). Lack of tension at kinetochores activates the spindle checkpoint in budding yeast. Curr. Biol. 11, 1462–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stricker, J., Maddox, P., Salmon, E.D., and Erickson, H.P. (2002). Rapid assembly dynamics of the Escherichia coli FtsZ-ring demonstrated by fluorescence recovery after photobleaching. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 3171–3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg, H.A., and Davis, T.N. (1997). A mutational analysis identifies three functional regions of the spindle pole component Spc110p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 8, 2575–2590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg, H.A., Goetsch, L., Byers, B., and Davis, T.N. (1996). Role of calmodulin and Spc110p interaction in the proper assembly of spindle pole body components. J. Cell Biol. 133, 111–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan, R., Hoang, C.P., and Verkman, A.S. (1997). Photobleaching recovery and anisotropy decay of green fluorescent protein GFP-S65T in solution and cells: cytoplasmic viscosity probed by green fluorescent protein translational and rotational diffusion. Biophys. J. 72, 1900–1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, T.U., Rachidi, N., Janke, C., Pereira, G., Galova, M., Schiebel, E., Stark, M.J., and Nasmyth, K. (2002). Evidence that the Ipl1-Sli15 (Aurora kinase-INCENP) complex promotes chromosome bi-orientation by altering kinetochore-spindle pole connections. Cell 108, 317–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wach, A., Brachat, A., Alberti-Segui, C., Rebischung, C., and Philippsen, P. (1997). Heterologous HIS3 marker and GFP reporter modules for PCR-targeting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 13, 1065–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasch, R., and Cross, F.R. (2002). APC-dependent proteolysis of the mitotic cyclin Clb2 is essential for mitotic exit. Nature 418, 556–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winey, M., Goetsch, L., Baum, P., and Byers, B. (1991). MPS1 and MPS 2, novel yeast genes defining distinct steps of spindle pole body duplication. J. Cell Biol. 114, 745–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S., Huang, H.K., Kaiser, P., Latterich, M., and Hunter, T. (2000). Phosphorylation and spindle pole body localization of the Cdc15p mitotic regulatory protein kinase in budding yeast. Curr. Biol. 10, 329–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariae, W., and Nasmyth, K. (1996). TPR proteins required for anaphase progression mediate ubiquitination of mitotic B-type cyclins in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 7, 791–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]