Abstract

Cyanobacteria, the progenitors of plant and algal chloroplasts, enabled aerobic life on earth by introducing oxygenic photosynthesis. In most cyanobacteria, the photosynthetic membranes are arranged in multiple, seemingly disconnected, concentric shells. In such an arrangement, it is unclear how intracellular trafficking proceeds and how different layers of the photosynthetic membranes communicate with each other to maintain photosynthetic homeostasis. Using electron microscope tomography, we show that the photosynthetic membranes of two distantly related cyanobacterial species contain multiple perforations. These perforations, which are filled with particles of different sizes including ribosomes, glycogen granules and lipid bodies, allow for traffic throughout the cell. In addition, different layers of the photosynthetic membranes are joined together by internal bridges formed by branching and fusion of the membranes. The result is a highly connected network, similar to that of higher-plant chloroplasts, allowing water-soluble and lipid-soluble molecules to diffuse through the entire membrane network. Notably, we observed intracellular membrane-bounded vesicles, which were frequently fused to the photosynthetic membranes and may play a role in transport to these membranes.

Keywords: cyanobacteria, electron tomography, intracellular trafficking, photosynthetic (thylakoid) membranes, vesicles

Introduction

Cyanobacteria, the progenitors of chloroplasts in algae and plants, were the first organisms to perform oxygenic photosynthesis on earth, making the development of aerobic life possible (De Marais, 2000; Falkowski, 2006). Photosynthetic electron transport and the consequent generation of proton-motive force that drives ATP synthesis are carried out, both in cyanobacteria and in chloroplasts, in flattened vesicles, called thylakoids (Menke, 1962, 1990). The thylakoids harbor the protein complexes that conduct the light-driven reactions of photosynthesis and provide a medium for energy transduction (Mustardy, 1996).

Driven by the need to accommodate a large surface area of thylakoid membranes within a small cell volume, most cyanobacteria adopted a geometry in which the thylakoids are organized in multiple concentric shells, like the layers of an onion (Nierzwickibauer et al, 1983) (for different configurations, see e.g., Liberton et al, 2006; van de Meene et al, 2006). In such an arrangement, it is unclear how communication between the cell interior and the plasma membrane (and, hence, the surrounding) is maintained, how solutes move between the compartments created by the shells (e.g., supplying thylakoids with proteins and lipids) and how the different shells or layers of the thylakoid membranes communicate with each other to ensure concerted responses to environmental changes or to incoming stimuli.

In the present work, we addressed these issues by performing dual-axis electron microscope tomography combined with cryo-fixation and freeze substitution on two remote cyanobacterial species: Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942, a fresh-water unicellular cyanobacterium (http://genome.jgi-psf.org/finished_microbes/synel/synel.home.html), and Microcoleus sp, a filamentous cyanobacterium abundant in biological desert crusts (Harel et al, 2004; Ohad et al, 2005). In both species, the thylakoid membranes contain multiple perforations that enable unperturbed traffic of molecules and inclusions throughout the cell. Different layers of the thylakoid membranes, rather than being independent, are connected to each other at multiple sites, forming a continuous network that encloses a single lumen. Finally, membrane-bounded vesicles, often seen fused to the thylakoid membranes, likely serve in transport to and from these membranes.

Results and discussion

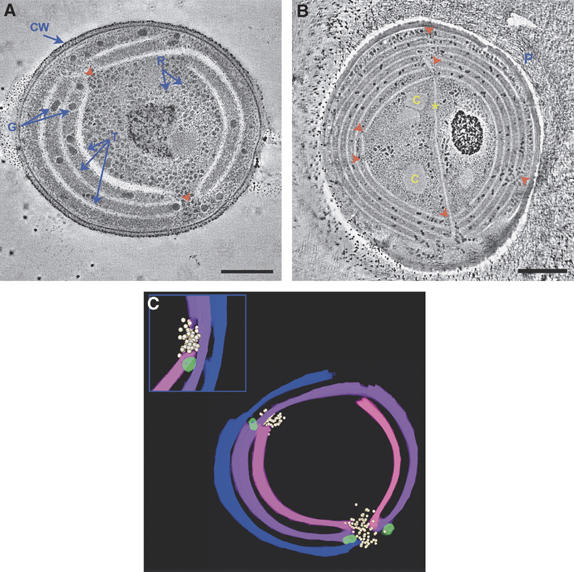

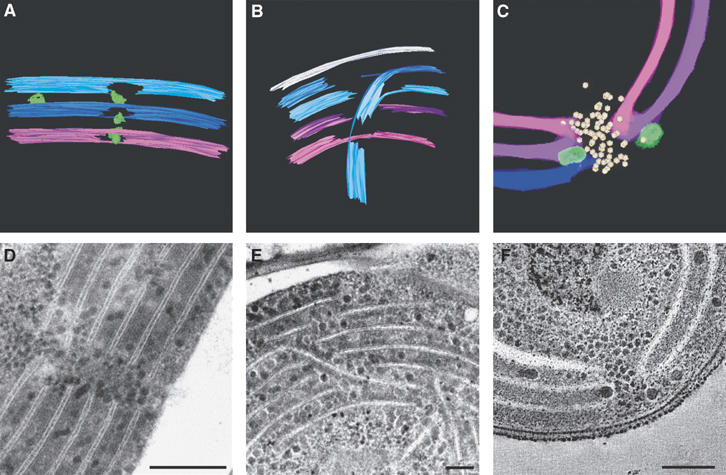

Figure 1 shows tomographic slices from dual-axis tomograms of cryo-immobilized, freeze-substituted Synechococcus sp PCC 7942 (A) and Microcoleus sp (B) cells. In both cases, the thylakoid membranes appear discontinuous. In three dimensions, these disruptions represent perforations or holes in the lamellae (Figure 1C and Supplementary Movies S1 and S2). Analysis of the images (six tomograms and ∼500 cells, in total) revealed that, on average, each Synechococcus PCC 7942 cell contains about 30 perforations in its thylakoid membranes. The number of perforations in the larger Microcoleus cells is greater, averaging ∼70 per cell. The diameter of the perforations varies substantially, ranging from 20 to 150 nm. Three major types of perforations or openings were identified. The first involves a simple opening in the lamellae (Figure 2A and D). Frequently, perforations of this type present in different layers are aligned, forming a passageway that traverses several membrane sheets. In the second type, the passageway is traversed by a strip of membranes (Figure 2B and E). These strips are formed by splitting or branching of the membranes from one layer, usually an outer one, which then bends toward and crosses the passageway. Openings belonging to the third type are formed by parallel sheets of membranes that are fused to each other on either side of the gap. The sheets may belong to adjacent layers (Figure 2C and F) or to layers separated by one or more sheets. In all three types, the perforations present in the membranes do not compromise the integrity of the sac-like nature of the thylakoids; the thylakoid vesicles remain sealed (Figures 2E and 3D and Supplementary Figures S1A, C, D and S2).

Figure 1.

Perforations in the thylakoid membranes of cyanobacteria. Tomographic slices (∼12 nm) from dual-axis tomograms of cryo-immobilized, freeze-substituted cells of (A) Synechococcus sp PCC 7942 and (B) Microcoleus sp. The complete sets of tomographic slices used to generate the volumes are provided (Supplementary Movies S1 and S2). A total of six tomograms and about 500 thin-section slices were examined and used in the analysis. In both species, the thylakoid membranes (T) are perforated at multiple sites (red arrowheads). Labels: CW, cell wall, both the inner and outer cell membranes are apparent; R, ribosomes; G, polysaccharide (glycogen) granules; C, carboxysomes; P, extracellular polysaccharides, which envelope filaments of Microcoleus sp (Ohad et al, 2005); asterisk, thylakoid membrane extension crossing the cell. The small black dots seen around the cells are gold particles used for image alignment. Scale bars, 200 nm (A); 500 nm (B). (C) Model of the thylakoid membranes of Synechococcus sp PCC 7942 generated from the tomographic data shown in (A). The inset shows a rotated view of the upper left hole. Ribosomes (white) and polysaccharide granules (light green) are seen near and inside the perforations.

Figure 2.

Types of perforations in the thylakoid membranes. The major types of perforations observed in the thylakoid membranes of Synechococcus sp PCC 7942 and Microcoleus sp are shown. Models (A) generated from a tomogram of a Microcoleus sp cell (not shown), (B) generated from Supplementary Movie S2; (C) an enlargement of the lower perforation seen in Figure 1C; thin-section micrographs of Microcoleus sp cells (D, E), and a tomographic slice (∼12 nm; F, an enlargement of Figure 1A). Scale bars, 200 nm (D); 80 nm (E); 100 nm (F).

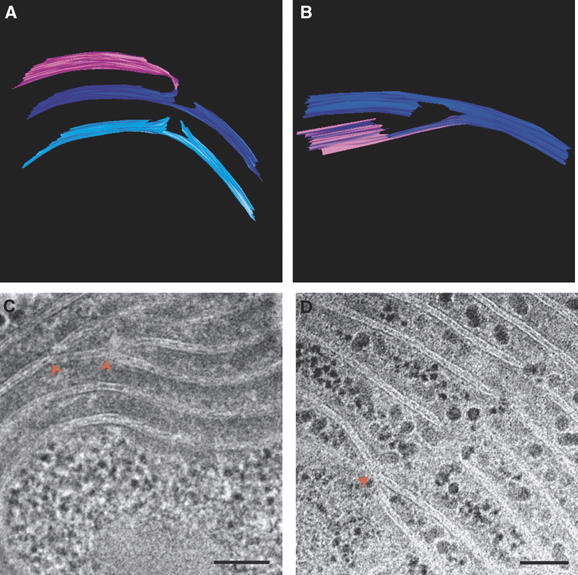

Figure 3.

Thylakoid membranes are interconnected. Models (A) generated from a tomogram of a Synechococcus cell (not shown), (B) generated from a tomogram of a Microcoleus cell (see Supplementary Movie S2); and thin-section micrographs of Microcoleus sp cells (C, D), showing how different layers of the thylakoid membranes are connected to each other. Connections involve splitting or branching of the membranes (red arrowheads) and subsequent folding or fusion. A similar mode of connectivity, involving bifurcations and fusion of the membranes, has also been observed in the thylakoid membranes of higher-plant chloroplasts (Shimoni et al, 2005). Scale bars, 100 nm.

Particles of different sizes were observed inside the membrane perforations (Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4 and Supplementary Figure S1). One type of particles observed very frequently was ribosomes, probably en route to the cell membrane, where cotranslational insertion of proteins takes place. Other particles visualized inside the holes were polysaccharide (glycogen) granules. These granules were particularly abundant in cells of Microcoleus sp, in which polysaccharides are used to form thick fibrous structures around the cells, protecting them against dehydration (Potts, 1994). Occasionally, we observed larger particles inside the holes, including lipid bodies (Pankratz and Bowen, 1963; Edwards et al, 1968; Wolk, 1973; Nierzwickibauer et al, 1983; van de Meene et al, 2006) (Supplementary Figure S2), which have been implicated in the trafficking of lipids to the thylakoid membranes (Pankratz and Bowen, 1963; Nierzwickibauer et al, 1983; Nierzwicki-Bauer et al, 1984), and large membrane-bounded vesicles (Supplementary Figure S3A, B and C). The fact that the perforations in the membranes are usually populated may suggest that the number of holes is limited compared to the load. Alternatively, perforations may be formed upon demand, in response to local cues.

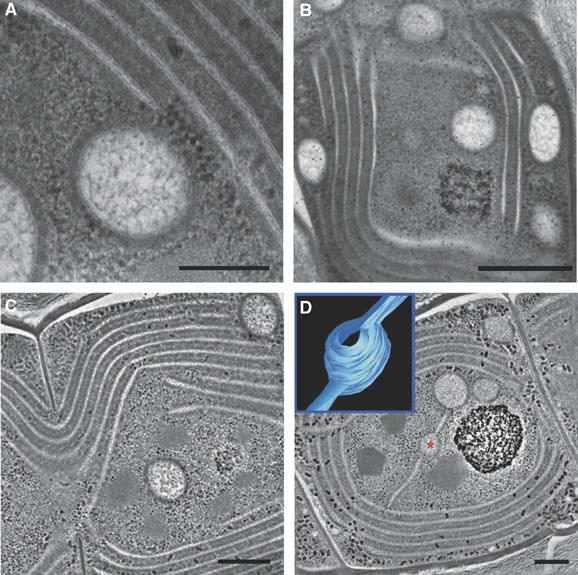

Figure 4.

Vesicles in Microcoleus sp cells. Thin-section micrographs (A, B) showing vesicles in which the delimiting bilayer is clearly visualized (A), and vesicles spread out throughout the center and periphery of the cell (B). Tomographic slices (∼12 nm; C, D; see complete tomograms provided, Supplementary Movies S3 and S4) of a vesicle found in the center of the cell (C) and vesicles connected to each other and to the thylakoid membrane network by protruding lamella (D). Inset in (D) shows a model of the vesicle marked by a red asterisk, depicting its connections to the flanking lamellae. The volume of the vesicle could not be reconstructed in whole, as the vesicle was not fully contained in the semi-thick section used for tomography. Scale bars, 200 nm (A); 500 nm (B); 300 nm (C, D). See also Supplementary Figure S3.

The presence of perforations in the membranes may also explain how thylakoids are replenished with membrane and/or luminal proteins. As ribosomes are capable of crossing the holes, cotranslational insertion of proteins into the membranes or into the confined lumen can, in principle, take place on any layer. However, as most of the space between neighboring layers is occupied by densely packed phycobilisomes (Tandeau de Marsac, 2003; van de Meene et al, 2006), the sites of insertion are expected to be limited to regions that surround the perforations. This may explain the high density of ribosomes inside or in close proximity to the latter (Figures 1, 2D and F). An important activity at these sites may be synthesis of the D1 subunit of the photosynthetic reaction center II, which is rapidly degraded due to photo-induced damage and needs to be supplied to the membranes continuously (Barber and Andersson, 1992; Adir et al, 2003).

Contrary to their appearance in (2D) thin-section micrographs, different shells or layers of the thylakoid membranes in the cyanobacterial cells are not independent. A characteristic feature observed in all the images is that thylakoid membranes that split from one layer are often fused to lamellae that branched off from another (Figure 3; see also Figures 1, 2 and 5). In addition, different layers converge at perforations belonging to the third type described above (Figure 2C and F). All layers are therefore connected to each other at multiple sites. The result is a continuous network enclosing a single lumen.

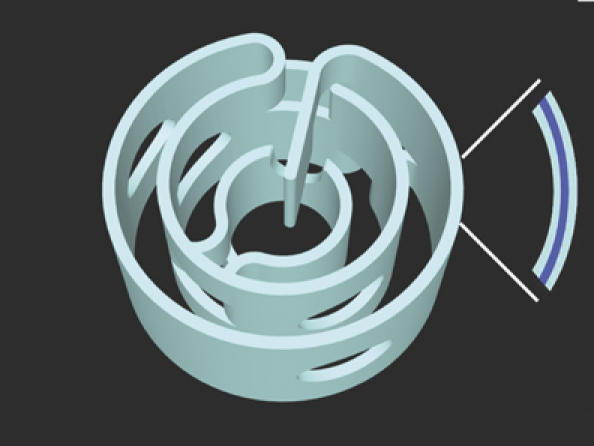

Figure 5.

Perforations and connectivity in the cyanobacterial thylakoid membranes. An artistic view of cyanobacterial thylakoid membranes, combining features observed in the two species examined in this work, including perforations, gaps, bifurcations and fusion. The result is a highly connected but perforated network of lamellae sharing a single, continuous lumen and allowing for unperturbed transport of molecules and macromolecules throughout the entire cell volume. A configuration capturing many of these features has been proposed by Mullineaux (1999). Note that layers represent paired membranes enclosing the thylakoid lumen (blue). Other views of the model are provided in Supplementary Movie S5.

The interconnectedness of the thylakoid layers provides continuous media for the movement of both water-soluble and lipid-soluble substances throughout the entire network. This, in turn, has important implications to the formation and function of the thylakoid membranes. One obvious consequence is that it allows for a concerted action of all thylakoids in response to perturbations or stimuli. It also simplifies the introduction of lipids and proteins into the membranes during biogenesis or repair, because it allows substances to enter the system at one point (e.g., a perforation site) and move to another by diffusion. On a more speculative note, the interconnectedness may facilitate modulation of the degree of asymmetry or inhomogeneity of the system. Such a modulation appears to be required for adaptation of the photosynthetic apparatus to variations in environmental conditions, in particular light. Dynamic redistribution of photosynthetic complexes is known to exist in chloroplast thylakoid membranes, where it plays a role in chromatic adaptation. ‘Radial asymmetry', where photosynthetic complexes are distributed unevenly among the inner and outer thylakoid layers, has been detected in Synechococcus sp PCC 7942 (Sherman et al, 1994). Furthermore, interconnectedness likely provides mechanical strength to the lamellar thylakoid sheets by reducing the available degrees of freedom of the system, thus reducing the risk of breakage or collapse.

Many of the features exhibited by the photosynthetic membranes of the two cyanobacterial species examined, namely bifurcations, bending, folding and fusion, are also observed in the thylakoid membranes of higher-plant chloroplasts and were assigned similar roles (Shimoni et al, 2005). Holes, serving as initiation sites for grana formation, have likewise been visualized in developing chloroplast thylakoid membranes (Brangeon and Mustardy, 1979). Thus, in spite of the gross differences in membrane architecture, as well as in the nature of light-harvesting complexes, the two membrane systems share many structural elements or designs. Given the evolutionary link between the two systems (Vothknecht and Westhoff, 2001; Falkowski et al, 2004, 2006), such preservation of structural motifs is not unexpected.

Notably, cells of Microcoleus sp contained large vesicles delimited by a membrane bilayer and enclosing a granular matrix (Figure 4 and Supplementary Figure S3). These vesicles are quite distinct from lipid bodies, which are frequently observed in cyanobacterial cells (see e.g., van de Meene et al, 2006 and reference therein), as they are membrane-bounded and substantially larger (150–300 nm in diameter compared to ∼50 nm), and their inner matrix is clearly different (Figure 4; Supplementary Figures S2 and S3; Supplementary Movies S3 and S4). The vesicles were dispersed throughout the cells, appearing in the cell center, periphery (Figure 4B–D and Supplementary Figure S3D–F) and inside the perforations in the thylakoid membranes (Supplementary Figure S3A–C), where they appear to be caught in transit between the plasma membrane and the cell interior. Tomographic examination of the vesicles revealed that they are either isolated (Figure 4C and Supplementary Movie S3) or, quite often, fused or connected to the thylakoid membranes or to other vesicles (Figure 4D and Supplementary Movie S4). The spherical shape of the vesicles is preserved even when they are connected to the thylakoids, indicating that the two membrane structures have different material properties. Consistent with this, the transition between the vesicle body and the lamellae is very sharp. This can be seen in the model shown in Figure 4D (inset) in which a vesicle is connected to two lamellar strips. Note that the two connections occur at different planes.

The vesicles seen in Microcoleus may serve in trafficking of lipids and/or proteins to and from the thylakoid membranes during recycling. They may also function in the transport of certain photosynthetic complexes from the cell membrane, where early steps of their biogenesis take place, to the thylakoids (Zak et al, 2001; Keren et al, 2005). In chloroplasts, vesicles have been observed to bud from the inner envelope membrane and it has been suggested that they may fuse to each other and to the thylakoid membranes (Carde et al, 1982; Hoober et al, 1991; Morre et al, 1991). A proposed mechanism in which lipids and proteins are transported from the inner envelope of the chloroplast to the thylakoids via vesicles implicates vesicular trafficking as a key mechanism in thylakoid formation (Andersson and Sandelius, 2004; Vothknecht and Soll, 2005). Three proteins, FZL, VIPP1 and Thf1, which have been implicated in membrane remodeling and vesicular trafficking in chloroplasts, are associated with the thylakoids and envelope membrane fractions of chloroplasts, and mutations therein affect thylakoid structure (Li et al, 1994; Kroll et al, 2001; Wang et al, 2004; Gao et al, 2006). VIPP1, vesicle-inducing protein in plastids 1 (Li et al, 1994), was also found in the plasma membrane of cyanobacteria, including Synechocystis sp PCC 6803 (Westphal et al, 2001a; Srivastava et al, 2006). Cells of this bacterium, in which VIPP1 is disrupted, contain few, sparsely distributed thylakoids instead of the usual, ordered arrays of membranes, and are unable to carry out light-stimulated oxygen evolution (Westphal et al, 2001a).

The frequency of appearance of vesicles in chloroplasts greatly varies with environmental conditions (Morre et al, 1991; Westphal et al, 2001b, 2003). Likewise, this may explain why vesicles were observed only in Microcoleus sp. Establishing the exact nature and role of these vesicles would require biochemical analysis. Nonetheless, the presence of membrane-bound vesicles in ancient prokaryotes such as cyanobacteria has important implications on the evolution of vesicular transport as it suggests that this mode of transport emerged early in evolution and did not evolve as part of the development of eukaryotes.

The findings presented in this work indicate that, in addition to maximizing photosynthetic efficiency, the photosynthetic membranes of cyanobacteria have been adapted to the need of maintaining facile intracellular transport. The structural elements that afford such communication (Figure 5; and see the configuration insightfully suggested by Mullineaux, (1999)) are also exploited to achieve a highly connected yet perforated lamellar system. This allows ribosomes, for example, to reach the different layers of the thylakoids, suggesting that biogenesis and repair of the photosynthetic apparatus can occur at the thylakoids themselves. The organizational strategy seen in the cyanobacteria studied here is preserved to a large extent in the thylakoid networks of higher-plant chloroplasts. It may be complemented, at least in some cyanobacteria, by a vesicular transport system similar to that of chloroplasts, which functions to supply thylakoids with different molecules, possibly including constituents of photosynthetic complexes. Notably, other thylakoid architectures exist. Recent electron microscopy studies of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp PCC 6803 revealed a complex, unusual thylakoid morphology (Liberton et al, 2006; van de Meene et al, 2006), in which some of the thylakoids vary in size and are isolated (Liberton et al, 2006). This organization may reflect a particular instance in which the perforated morphology described here is brought to an extreme.

One of the characteristic features of the thylakoid membrane is its ability to adapt to variations in environmental conditions. Thus, the thylakoid network, both in cyanobacteria and chloroplasts, is likely to be of a highly dynamic nature. Given its complexity even in cyanobacteria, maintaining this network and modulating its morphology during adaptation likely involves dedicated machinery, perhaps similar to those operating in the mitochondria and Golgi apparatus.

Materials and methods

S. elongatus PCC 7942 and Microcoleus sp were grown as described previously (Harel et al, 2004; Ohad et al, 2005; Balint et al, 2006). Exponentially grown cells were cryo-immobilized in an HPM 010 high-pressure freezer (BAL-TEC AG, Lichtenstein), freeze-substituted (Leica EM AFS, Vienna, Austria) in dry acetone containing 2% glutaraldehyde and 0.1% tannic acid for 60 h at −90°C, and then slowly warmed up to 0°C. Following acetone rinses, the samples were incubated in 0.1% uranyl acetate and 1% OsO4 for 1 h at room temperature. Samples were then washed with dry acetone, infiltrated with increasing concentrations of epon over 6 days and polymerized at 60°C. Sections were cut using an Ultracut UCT microtome (Leica, Vienna, Austria) and post-stained with 5% uranyl acetate in isobutanol-saturated double-distilled water (DDW) and Reynold's lead citrate in isobutanol-saturated DDW (Roberts, 2002). This protocol was used for thin-section transmission electron microscopy (TEM) as well as for electron tomography. Thin sections (70 nm) were examined in an FEI Tecnai T12 TEM operating at 120 kV. For electron tomography, double-tilt series of semi-thick sections (∼150 nm), decorated on both sides with 12 nm colloidal gold markers for subsequent image alignment, were acquired in FEI Tecnai F-20 TEM operating at 200 kV. Images were recorded on a 4k × 4k TemCam F415 CCD camera (TVIPS, Gauting, Germany). Image acquisition was performed at 1.5° intervals over a range of ±65°, using the SerialEM program for automated tilt series collection (Mastronarde, 2005). Alignment, 3D reconstruction and modeling were performed using the IMOD image-processing package (Kremer et al, 1996). Movies were made using IMOD and QuickTime Pro (Apple, USA). Images were analyzed using analySIS software (Soft Imaging System GmbH, Germany).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Movie S1

Supplementary Movie S2

Supplementary Movie S3

Supplementary Movie S4

Supplementary Movie S5

Supplementary Figure S1

Supplementary Figure S2

Supplementary Figure S3

Supplementary Figures Legends

Acknowledgments

We thank Avi Minsky, Vlad Brumfeld, Silvia Chuartzman, Itay Rousso, Ruti Kapon and Ophir Rav-Hon for helpful discussions. This research was supported by grants from the Henry Legrain Foundation (ES); the Israel Science Foundation (ISF) and the German Bundes Ministerium für Bildung Wissenschaft (BMBF) (AK); the Avron, Even-Ari Minerva Center for Photosynthesis Research (IO); the Avron-Wilstätter Minerva Center for Photosynthesis Research (ZR).

References

- Adir N, Zer H, Shochat S, Ohad I (2003) Photoinhibition—a historical perspective. Photosynth Res 76: 343–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson MX, Sandelius AS (2004) A chloroplast-localized vesicular transport system: a bio-informatics approach. BMC Genomics 5: 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balint I, Bhattacharya J, Perelman A, Schatz D, Moskovitz Y, Keren N, Schwarz R (2006) Inactivation of the extrinsic subunit of photosystem II, PsbU, in Synechococcus PCC 7942 results in elevated resistance to oxidative stress. FEBS Lett 580: 2117–2122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber J, Andersson B (1992) Too much of a good thing: light can be bad for photosynthesis. Trends Biochem Sci 17: 61–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brangeon J, Mustardy L (1979) Ontogenetic assembly of intra-chloroplastic lamellae viewed in 3-dimension. Biol Cell 36: 71–80 [Google Scholar]

- Carde JP, Joyard J, Douce R (1982) Electron-microscopic studies of envelope membranes from spinach plastids. Biol Cell 44: 315–324 [Google Scholar]

- De Marais DJ (2000) Evolution. When did photosynthesis emerge on Earth? Science 289: 1703–1705 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards MR, Berns DS, Ghiorse WC, Holt SC (1968) Ultrastructure of thermophilic blue-green alga Synechococcus lividus copeland. J Phycol 4: 283–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkowski PG, Katz ME, Knoll AH, Quigg A, Raven JA, Schofield O, Taylor FJ (2004) The evolution of modern eukaryotic phytoplankton. Science 305: 354–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkowski PG (2006) Evolution. Tracing oxygen's imprint on earth's metabolic evolution. Science 311: 1724–1725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H, Sage TL, Osteryoung KW (2006) FZL, an FZO-like protein in plants, is a determinant of thylakoid and chloroplast morphology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 6759–6764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harel Y, Ohad I, Kaplan A (2004) Activation of photosynthesis and resistance to photoinhibition in cyanobacteria within biological desert crust. Plant Physiol 136: 3070–3079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoober JK, Boyd CO, Paavola LG (1991) Origin of thylakoid membranes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii y-1 at 38 degrees C. Plant Physiol 96: 1321–1328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keren N, Liberton M, Pakrasi HB (2005) Photochemical competence of assembled photosystem II core complex in cyanobacterial plasma membrane. J Biol Chem 280: 6548–6553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer JR, Mastronarde DN, McIntosh JR (1996) Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. J Struct Biol 116: 71–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroll D, Meierhoff K, Bechtold N, Kinoshita M, Westphal S, Vothknecht UC, Soll J, Westhoff P (2001) VIPP1, a nuclear gene of Arabidopsis thaliana essential for thylakoid membrane formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 4238–4242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li HM, Kaneko Y, Keegstra K (1994) Molecular cloning of a chloroplastic protein associated with both the envelope and thylakoid membranes. Plant Mol Biol 25: 619–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberton M, Howard Berg R, Heuser J, Roth R, Pakrasi HB (2006) Ultrastructure of the membrane systems in the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. Protoplasma 227: 129–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastronarde DN (2005) Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. J Struct Biol 152: 36–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menke W (1962) Structure and chemistry of plastids. Annu Rev Plant Physiol 13: 27–44 [Google Scholar]

- Menke W (1990) Retrospective of a Botanist. Photosynth Res 25: 77–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morre DJ, Sellden G, Sundqvist C, Sandelius AS (1991) Stromal low temperature compartment derived from the inner membrane of the chloroplast envelope. Plant Physiol 97: 1558–1564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullineaux CW (1999) The thylakoid membranes of cyanobacteria: structure, dynamics and function. Aust J Plant Physiol 26: 671–677 [Google Scholar]

- Mustardy L (1996) Development of thylakoid membrane stacking. In Oxygenic Photosynthesis: The Light Reactions, Ort DR, Yocum CF (eds) Vol. 4, pp 59–68. Dodrecht, Boston, London: Kluwer Academic Publishers [Google Scholar]

- Nierzwicki-Bauer SA, Balkwill DL, Stevens SE Jr (1984) Heterocyst differentiation in the cyanobacterium Mastigocladus laminosus. J Bacteriol 157: 514–525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nierzwickibauer SA, Balkwill DL, Stevens SE (1983) 3-Dimensional ultrastructure of a unicellular cyanobacterium. J Cell Biol 97: 713–722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohad I, Nevo R, Brumfeld V, Reich Z, Tsur T, Yair M, Kaplan A (2005) Inactivation of photosynthetic electron flow during desiccation of desert biological sand crusts and Microcoleus sp. enriched isolates. Photochem Photobiol Sci 4: 977–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankratz HS, Bowen CC (1963) Cytology of blue-green algae. I. The cells of Symploca muscorum. Am J Bot 50: 387–399 [Google Scholar]

- Potts M (1994) Desiccation tolerance of prokaryotes. Microbiol Rev 58: 755–805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts IM (2002) Iso-butanol saturated water: a simple procedure for increasing staining intensity of resin sections for light and electron microscopy. J Microsc 207: 97–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman DM, Troyan TA, Sherman LA (1994) Localization of membrane proteins in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC7942 (radial asymmetry in the photosynthetic complexes). Plant Physiol 106: 251–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoni E, Rav-Hon O, Ohad I, Brumfeld V, Reich Z (2005) Three-dimensional organization of higher-plant chloroplast thylakoid membranes revealed by electron tomography. Plant Cell 17: 2580–2586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava R, Battchikova N, Norling B, Aro EM (2006) Plasma membrane of Synechocystis PCC 6803: a heterogeneous distribution of membrane proteins. Arch Microbiol 185: 238–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandeau de Marsac N (2003) Phycobiliproteins and phycobilisomes: the early observations. Photosynth Res 76: 193–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Meene AM, Hohmann-Marriott MF, Vermaas WF, Roberson RW (2006) The three-dimensional structure of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Arch Microbiol 184: 259–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vothknecht UC, Soll J (2005) Chloroplast membrane transport: interplay of prokaryotic and eukaryotic traits. Gene 354: 99–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vothknecht UC, Westhoff P (2001) Biogenesis and origin of thylakoid membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1541: 91–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Sullivan RW, Kight A, Henry RL, Huang J, Jones AM, Korth KL (2004) Deletion of the chloroplast-localized thylakoid formation1 gene product in Arabidopsis leads to deficient thylakoid formation and variegated leaves. Plant Physiol 136: 3594–3604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal S, Heins L, Soll J, Vothknecht UC (2001a) Vipp1 deletion mutant of Synechocystis: a connection between bacterial phage shock and thylakoid biogenesis? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 4243–4248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal S, Soll J, Vothknecht UC (2001b) A vesicle transport system inside chloroplasts. FEBS Lett 506: 257–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal S, Soll J, Vothknecht UC (2003) Evolution of chloroplast vesicle transport. Plant Cell Physiol 44: 217–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolk CP (1973) Physiology and cytological chemistry of blue-green-algae. Bacteriol Rev 37: 32–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zak E, Norling B, Maitra R, Huang F, Andersson B, Pakrasi HB (2001) The initial steps of biogenesis of cyanobacterial photosystems occur in plasma membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 13443–13448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Movie S1

Supplementary Movie S2

Supplementary Movie S3

Supplementary Movie S4

Supplementary Movie S5

Supplementary Figure S1

Supplementary Figure S2

Supplementary Figure S3

Supplementary Figures Legends