Abstract

Naturally occurring mutations in two separate, but interacting loci, pkd1 and pkd2 are responsible for almost all cases of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD). ADPKD is one of the most common genetic diseases resulting primarily in the formation of large kidney, liver, and pancreatic cysts. Homozygous deletion of either pkd1 or pkd2 results in embryonic lethality in mice due to kidney and heart defects illustrating their indispensable roles in mammalian development. However, the mechanism by which mutations in these genes cause ADPKD and other developmental defects are unknown. Research in the past several years has revealed that PKD2 has multiple functions depending on its subcellular localization. It forms a receptor-operated, non-selective cation channel in the plasma membrane, a novel intracellular Ca2+ release channel in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and a mechanosensitive channel in the primary cilium. This review focuses on the functional compartmentalization of PKD2, its modes of activation, and PKD2-mediated signal transduction.

Keywords: PKD2, ADPKD, TRP channels, PIP2, PLC, Cilium, Centrosome, TRPP2, mechanotransduction

Introduction

polycystic kidney disease -2 gene (pkd2) was first identified as one of the genes mutated in families with type 2 ADPKD which accounts for about 15% of all cases of ADPKD [1]. The remaining 85% of the cases are caused by mutations in another gene called pkd1 (type 1 ADPKD) [2–4]. Apart from the fact that type 1 ADPKD can have a more severe phenotype and manifested earlier in life than type 2, both types represent virtually the same disease [5]. In terms of the disease phenotype, ADPKD is a common systemic disease affecting multiple organs and cell types [5, 6]. It affects 1 in 400 to 1,000 individuals primarily by the development of large, fluid-filled renal cysts that ultimately may lead to kidney failure. In addition to kidney cysts, ADPKD patients develop cysts in the liver and the pancreas. Intracranial aneurisms have also been observed in a smaller percentage of these patients [5, 6].

The protein products of pkd1 and pkd2, originally called PKD1 and PKD2 or polycystin-1 and 2, respectively, are large, membrane-associated proteins with putative roles in signal transduction and Ca2+ regulation [7–10]. PKD2 or TRPP2 (its current name) structurally belongs to the transient receptor potential (TRP) superfamily of ion channels [11]. TRP channels are predicted to span the plasma membrane six times with their N- and C-termini located inside the cell [12]. The ionic pore is expected to be formed by the short extracellular loop connecting transmembrane segments 5 and 6 (S5 and S6). TRP channels have been implicated in diverse cellular functions ranging from osmosensing and mechanotransduction to regulation of Mg2+ homeostasis and vasoregulation [12, 13].

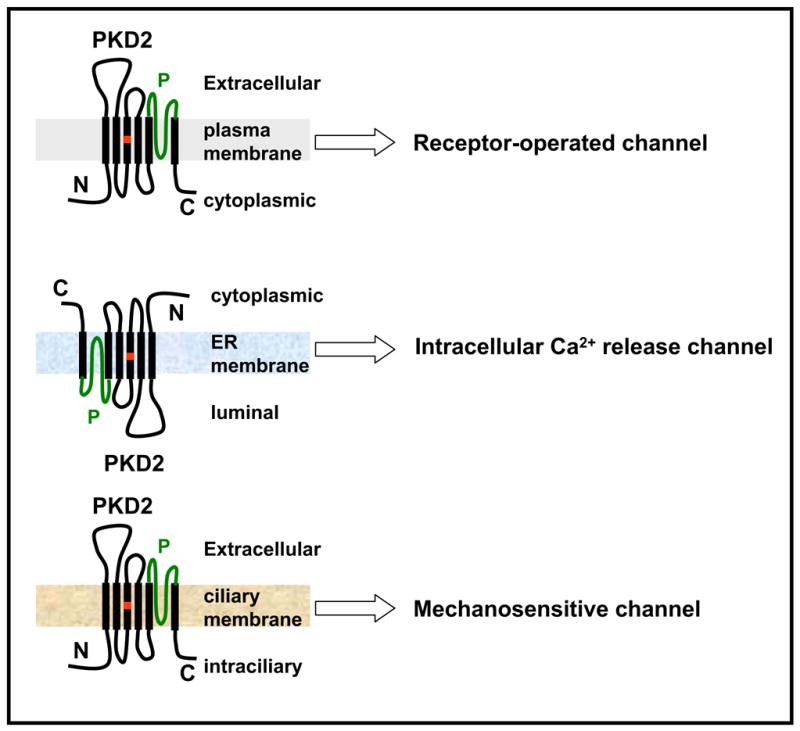

At the cellular level, they act downstream of phospholipase C (PLC) and are believed to function as cellular sensors activated by a wide variety of intracellular and extracellular stimuli [14]. With the exception of TRPV5 and TRPV6, which are highly Ca2+ selective and TRPM4 which is practically impermeable to Ca2+, all other members of the TRP superfamily form non-selective cation channels in the plasma membrane, which permeate divalent cations to various degrees [15]. In terms of their subcellular localizations, TRP channels have been localized in various subcellular sites such as plasma membrane [12], endoplasmic reticulum [16], lysosomes [17–19], and primary cilium [20–22]. Consistently, PKD2 expression has been reported in the plasma membrane [23, 24], ER [25], primary cilium [26], centrosome [27], and mitotic spindles in dividing cells [28]. Specific functions of PKD2 have been associated with its expression in the plasma membrane, ER, and primary cilium (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Functional compartmentalization of PKD2. PKD2 is thought to function as a receptor-operated non-selective cation channel at the plasma membrane, an intracellular Ca2+ release channel in the ER, and a mechanosensitive channel in the cilium. The location of the D511V mutation is shown in red and the putative pore (P)-forming region is shown in green.

Functional compartmentalization of PKD2

Function at the plasma membrane

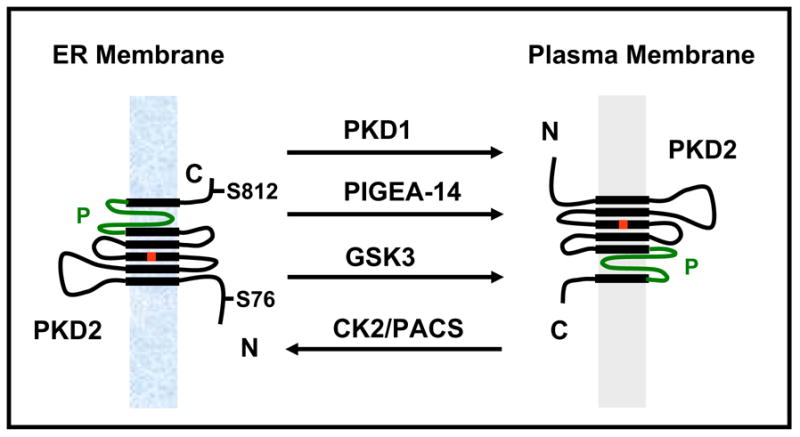

Functional expression of PKD2 as an ion channel was first reported by Hanaoka et al [29]. In this study, it was demonstrated that PKD2 alone was unable to form a functional channel in CHO-K1 cells, but in association with PKD1, PKD2 displayed channel activity. Some of the biophysical properties such as cation selectivity and regulation by Ca2+ were in agreement with a previous study on the structurally related channel, PKD2L1 [30]. In the PKD1-PKD2 coexpression study [29], it was also shown that PKD1 facilitated the targeting of PKD2 to the plasma membrane which was necessary for channel activity. In further support of the relevance of the interaction to ADPKD, naturally occurring mutations in PKD1 or PKD2 that would eliminate their interaction resulted in loss of channel activity. Therefore, this study set the stage for functional expression PKD2 and indicated that the role of PKD1 was simply to chaperone PKD2 to the plasma membrane, where PKD2 formed a constitutively active channel. Subsequently, single channel studies in placental preparations [31], heterologously expressed PKD2 in Xenopus oocytes [32] and HEK293 cells [33], and in vitro translated purified PKD2 in cell-free systems [31] further characterized PKD2 activity. Despite subtle disparities among these studies [34], it was concluded that PKD2 could form a functional channel in the plasma membrane with constitutive activity upon overexpression. It allowed non-selective passing of cations, with slightly higher selectivity for Ca2+ over Na+ and K+, but higher conductance in K+ [34]. However, the high single channel conductance (100–200 pS) [24, 31, 35] in combination with the relatively high open probability (~20–40%) [24, 31, 35] did not correlate well with the moderate amplitude of whole cell currents (several hundreds pA at -100 mV) in cells overexpressing PKD2 [35, 36]. This, along with the observation that the vast amount of PKD2 was in the ER [25] raised the question of whether PKD2 alone or even in combination with PKD1 could actually form a functional channel in the plasma membrane. It is now accepted that PKD2 can function at the plasma membrane, but its activity there is under complex regulation involving shuttling between ER and plasma membrane, protein-protein interactions, and modes of activation. Specifically, it has been shown that the amount of PKD2 in the plasma membrane is dynamically regulated by interacting proteins (PKD1 [29, 35], Polycystin-2 interactor, Golgi- and ER-associated protein-14 (PIGEA-14) [37]), posttranslational modifications (serine phosphorylation by casein kinase 2 (CK2) [38] and glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) [39]), interaction with other channel subunits in the plasma membrane (PKD1 [29, 35, 40–42], TRPC1 [11], TRPV4 [43]) (Fig. 2), and finally, activation secondary to cell surface receptor activation (epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [36]).

Fig. 2.

Dynamic regulation of PKD2 trafficking from the ER to the plasma membrane. Physical interactions with PKD1 and PIGEA-14 or phosphorylation at S76 by GSK3 facilitate PKD2 movement from the ER to the plasma membrane, while phosphorylation at S812 by CK2 and binding to PACS proteins sequesters PKD2 in the ER.

Function at the ER

Cai et al first reported that native or transfected PKD2 was accumulated in the ER [25]. While it was expected that a channel protein destined to be forwarded to the plasma membrane would show considerable expression in the ER while en route to the plasma membrane, Cai et al [25] could not detect a significant amount of PKD2 in the plasma membrane. In fact, careful EndoH/PNGaseF experiments revealed that PKD2 could not get past the ER. Deletion studies identified a cluster of acidic residues in the C-terminal cytosolic tail of PKD2 that was responsible for the retention of the protein in the ER [25]. Interestingly, the pathogenic mutant PKD2(742X) which lacked the ER retention signal was forwarded to the plasma membrane and displayed constitutive channel activity [35, 44]. However, according to Hanaoka et al this mutant did not display channel activity [29]. Nevertheless, it is possible that plasma membrane expression of PKD2 is not sufficient for function, but perhaps interactions with other subunits are needed for channel activity. It was subsequently shown that PKD2 functioned as a novel intracellular Ca2+ channel which was activated in response to increases in intracellular Ca2+ concentration [45]. Single channel studies indicated that ER-reconstituted PKD2 displayed channel activity and Ca2+ imaging experiments revealed that PKD2 overexpression enhanced the amplitude and duration of G protein coupled receptor (GPCR) - induced Ca2+ release transients in the kidney epithelial cell line, LLC-PK1 [45]. It was shown in the same study that PKD2 overexpression did not alter the Ca2+ content of the intracellular stores as the response to the SERCA inhibitor, thapsigargin was identical between mock- and PKD2-transfected cells. Moreover, PKD2 activity was solely dependent on intracellular rather than extracellular Ca2+. Therefore these data indicated that PKD2 functioned exclusively as an intracellular Ca2+ induced Ca2+ release channel in kidney epithelial cells. The implication of these findings was that it could enhance local intracellular Ca2+ concentration in response to an initial rise in Ca2+ and therefore, PKD2 could regulate intracellular Ca2+ concentration in a localized fashion. Subsequent reports confirmed the role of PKD2 in intracellular Ca2+ release and further showed that it interacted with the isoform 1 of the IP3 receptor (IP3R1) [46]. However, PKD2 overexpression augmented mostly the duration rather than the amplitude of the Ca2+ release transient. Moreover, overexpression of the naturally occurring mutant PKD2-D511V had a dominant negative effect on Ca2+ release transients [46] lending support to the idea that endogenous PKD2 was likely to function as an intracellular Ca2+ -induced Ca2+ release channel. Experiments in vascular smooth muscle cells [47] and immortalized lymphoblasts [48] from PKD2 knock out mice and ADPKD patients, respectively, showed that PKD2 played a role in G protein coupled receptor-induced Ca2+ signaling, but the possibility that PKD2 could have also contributed to Ca2+ signaling through Ca2+ influx was not clearly addressed in these studies. Overall, despite the differences, there is significant gain- and loss-of-function evidence to suggest that in addition to residing in the ER, PKD2 also has a functional role in regulating intracellular Ca2+ release in response to localized changes in intracellular Ca2+.

Regulated trafficking between ER and plasma membrane

Köttgen et al [38] reasoned that the ER and plasma membrane pools of PKD2 must be dynamically regulated so that PKD2 activity can be tightly controlled (Fig. 2). They showed that serine phosphorylation within the ER retention sequence by CK2 reconstituted a binding site for a group of proteins called phosphofurin acidic cluster proteins 1 and 2 (PACS 1 and 2). Binding of PACS2 to PKD2 prevented its movement to the plasma membrane. Conversion of S812 to A within the acidic cluster in human PKD2 resulted in increased expression in the plasma membrane in cultured kidney epithelial cells [38]. Support for this model was obtained by the heterologous expression of wild type and S812A mutant form of PKD2 in Xenopus oocytes [38]. Injection of wild type PKD2 cRNA had no significant effect on channel activity, whereas injection of the S812A mutant resulted in large Na+ currents mediated by PKD2. In support of the idea that protein phosphorylation may regulate the amount of PKD2 in the plasma membrane, Streets et al [39] showed that constitutive phosphorylation of S76 of human PKD2 by GSK3 was necessary for its targeting to the plasma membrane (Fig. 2). Mutation of S76 (or S80 in zebrafish) to A resulted in PKD2 accumulation in intracellular compartments and failed to rescue the cystic phenotype in zebrafish injected with a pkd2-specific antisense morpholino oligonucleotide [39]. Interestingly, the S76/S80 mutation did not affect the ciliary expression of PKD2, questioning the functional role of PKD2 in the primary cilium in zebrafish. It would be interesting to know whether the S76/S80 mutation affected PKD2 channel function in the ER. In a separate study, Hidaka et al [37] identified PIGEA-14 as an interacting protein with PKD2 and proposed that binding to PIGEA-14 facilitated the movement of PKD2 from the ER to the Golgi (Fig. 2). In conclusion, all these studies illustrate the fact that the amount of PKD2 in the plasma membrane can be regulated. Further, this regulation has functional consequences as it may represent a surrogate mode of activation, if PKD2 forms a constitutively active channel in physiological conditions.

Function at the primary cilium

Almost all cell types have a monocilium, a microtubule-based structure protruding into the extracellular space [49]. In the case of an epithelial cell, the primary cilium is localized in the apical surface. The cilium is formed from the basal body in growth arrested cells [49]. While the exact function of the immotile, primary cilium of kidney epithelial cells is not well understood, it is now well established that loss of ciliary function and/or formation results in cystic diseases pointing to a central role of this organelle in PKD pathophysiology [50, 51]. Because cilia function as sensory organelles in the olfactory and vision systems [52], it is believed it may have a similar sensory function in the renal epithelial cells [53, 54]. Such a function could be fluid flow sensing [54]. In support of this hypothesis, it has been shown that mechanical bending of the primary cilium or fluid flow in MDCK cells resulted in increases in intracellular Ca2+ concentration which was dependent on extracellular Ca2+, PLC activation and inositol 1,4,5 trisphosphate (IP3)-induced release of intracellular Ca2+ stores [55–57]. It is noteworthy that bending-induced Ca2+ signaling was not affected by inhibition of ryonodine receptors [55]. Several groups have shown the expression of PKD1 and PKD2 in the primary cilium [24, 26, 58, 59]. Recently Geng et al [59] identified an N-terminal R6VxP motif responsible for PKD2 targeting to the cilium. They also found that PKD2 did not require PKD1 for targeting to the cilium. The assumption that PKD2 works independently of PKD1 in the cilium is also supported by the lack of PKD1 expression in the cilia of the embryonic node [60], an area that the function of PKD2 has been documented [61]. In regard to the function of PKD2 at the cilium, Nauli et al [62] presented the first evidence that PKD1 or PKD2 was necessary for fluid flow-induced Ca2+ signaling. They showed that renal epithelial cells responded to fluid flow by an increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration through the action of PKD1 or PKD2. Moreover, they showed that the cilium was absolutely required for fluid flow sensing. Cells derived from mice lacking pkd1 did not show a significant increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration in response to fluid flow. A similar effect was described when normal kidney epithelial cells were incubated with an antibody against a portion of the extracellular domain of PKD1 or the first extracellular loop of PKD2, between transmembrane segments 1 and 2. Therefore this report indicated that PKD1 and PKD2 were required for fluid flow sensing and so was the cilium. However, PKD1 and PKD2-mediated Ca2+ signaling was independent of PLC activation and inhibited by ryonodine and caffeine [62]. These data were in sharp contrast to the data obtained earlier on cilium-bending and fluid flow-induced Ca2+ signaling in MDCK cells [55], suggesting that PKD1 and PKD2 modulate Ca2+ signaling through a completely different signaling mechanism from cilium bending. The reasons for these discrepancies are unknown. It is also interesting to note that addition of the MR3 antibody, which recognized a different region in the extracellular domain of PKD1 from the region recognized by p96521 (amino acid residues 866–882), resulted in an increase in PKD2 activity through PKD1-mediated gating [35]. Although it could be possible that antibody binding to different epitopes in the extracellular domain of PKD1 could result in activation or inhibition, it would be interesting to test whether addition of MR3 in kidney epithelia cells could fail to induce an additional increase in response to fluid flow. These data would indicate that fluid flow-induced activation of PKD2 could occur through gating by PKD1. Nevertheless, the data were consistent with the hypothesis that PKD1 and PKD2 have a similar role in mechanotrasduction in the cilium. However, it was not addressed directly whether they functioned in concert. Nauli et al [62] showed that loss of pkd1 resulted in complete loss of fluid-flow-induced Ca2+ entry indicating that PKD1 was a part of the basic mechanosensing machinery in the cilium. This finding was consistent with the hypothesis that PKD1 functions as the actual sensor (or fluid-flow receptor), which could be coupled not only to PKD2 but also to other mechanosensitive channels present in the cilium such as TRPV4 [63] and TRPC1 [22]. Therefore, it is conceivable that deletion of pkd1 could result in complete loss of the Ca2+ response. The exact role of PKD2 in ciliary mechanosensation is less clear because the antibody raised against an internal epitope of PKD2 (negative control) blocked about 50% of fluid flow-induced increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration when it was applied in the extracellular space [62]. Therefore, it is difficult to know whether PKD2 accounted for the entire response or it partially contributed (maybe by ~ 50%) to fluid flow-induce Ca2+ signaling. An additional complicating factor in studying changes in intracellular Ca2+ concentration in response to a stimulus localized far from the cell body is that Ca2+ has a short ionic diffusion co-efficient (~1,000 μ m2/s) [64] preventing it from traveling long distances. Therefore, it is not expected to travel further than 0.5 μ m from the point of entry before encountering a Ca2+-binding protein. A recent proteomic study in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii identified 27 EF-containing peptides in purified flagellar preparations [65]. Therefore, it is difficult to envision how Ca2+ ions flowing through the PKD1/PKD2 complex distributed throughout the cilium could migrate 10–15 μ m, which is the average length of a cilium, to reach the ER in the cytoplasm to trigger Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release as was proposed by Nauli et al [62]. One possibility is that PKD1 and/or PKD2 may actually function at the very base of the cilium or essentially at the plasma membrane to sense fluid flow. This would be consistent with the notion that cysts in ADPKD can arise from any segment of the nephron including the intercalated cells which lack cilia. Alternativel, PKD1 and PKD2 may function throughout the cilium to mediate receptor-operated Ca2+ entry rather than strictly mechanosensation. In this case, Ca2+ binding proteins/effectors should be present in the cilium. This suggestion is supported by the presence of Ca2+-binding proteins in the flagellum [65] and more recent studies showing that Hedgehog [66–68] and platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFR α) signaling [69] occurs in the cilium, indicating that the cilium may actually function as a platform for signal transduction. Interestingly, PKD2 has been shown to be activated by EGF in the plasma membrane [36] and to co-localize in the primary cilium with the EGFR and phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-bisphosphate (PIP2) [36].

Function at the mitotic spindles and centrosome

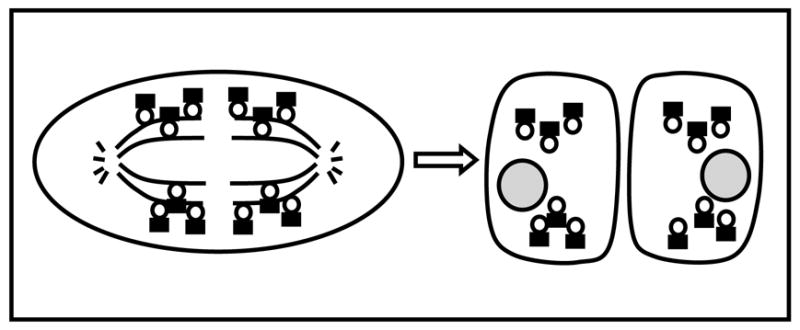

In addition to plasma membrane, ER, and primary cilium, PKD2 expression has been detected in the mitotic spindles [28] and centrosome [27] in dividing and resting cells, respectively. However, its functional role in these two cellular structures is unclear. Rundle et al [28] showed that the diaphanous related formin (mdia1), a downstream effector of Rho(A–C) proteins, was responsible for anchoring PKD2 at the spindles through a physical interaction. Knockdown of endogenous mdia1 in HeLa cells reduced PKD2-specific immunoreactivity from the spindles and the amplitude of intracellular Ca2+ release transients in response to histamine receptor activation, a typical GPCR, in dividing cells. These data led Rundle et al [28] to propose that the presence of PKD2 in the mitotic spindles may serve two, not necessarily mutually exclusive roles, to ensure symmetric distribution of PKD2 between mother and daughter cells (Fig. 3), and to regulate Ca2+ signaling during cell division. However, it was not shown directly whether PKD2 was responsible for the effect of mdia1 knockdown on Ca2+ release transients. It is possible that mdia1 might have regulated Ca2+ signaling independently of PKD2. Therefore, a possible role of PKD2 in Ca2+ signaling in dividing cells is likely, but it has not been documented yet.

Fig. 3.

Symmetric distribution of PKD2 between mother and daughter cells during cell division. PKD2 (shown as dark rectangular) is anchored to the mitotic spindles through a physical interaction with mdia1 (shown as open circle) during metaphase. As a result, mother and daughter cell receive equal amounts of PKD2.

Jurczyk et al [27] reported PKD2 expression in the centrosome in resting cells and the spindle poles of cells in metaphase. Moreover, PKD2 was found to co-immunoprecipitate with pericentrin and other components of the intraflagellar transport (IFT) machinery. Knockdown of pericentrin resulted in loss of cilia. Therefore, the authors proposed that PKD2, pericentrin, and IFT proteins may be required for ciliary function and assembly. While the mechanism by which all these proteins and particularly PKD2, function to assemble cilia is unknown, the study by Jurczyk et al [27] puts forth the very attractive concept, that PKD2 may actually function upstream of ciliary formation, at the level of the centrosome. Recent work in Drosophila has shown that deletion of centrosomal protein AKAP450 [70] and DSas-4 [71], a Drosophila homolog of the centrosomal protein CenpJ, resulted in loss of centrosomes and cilia. Interestingly, loss of centrosomes did not have an effect on mitosis [71]. Therefore, loss of cilia can occur independently of an effect on cell cycle through centrosomal proteins. While a structural or scaffolding role of pericentrin in centrosome and ciliary formation can be envisioned, it is difficult to predict a role of PKD2 as an ion channel in the centrosome. Nevertheless, given the role of PKD2 in intracellular Ca2+ signaling [45], such a possibility remains an intriguing one.

Modes of PKD2 activation

Activation by EGF

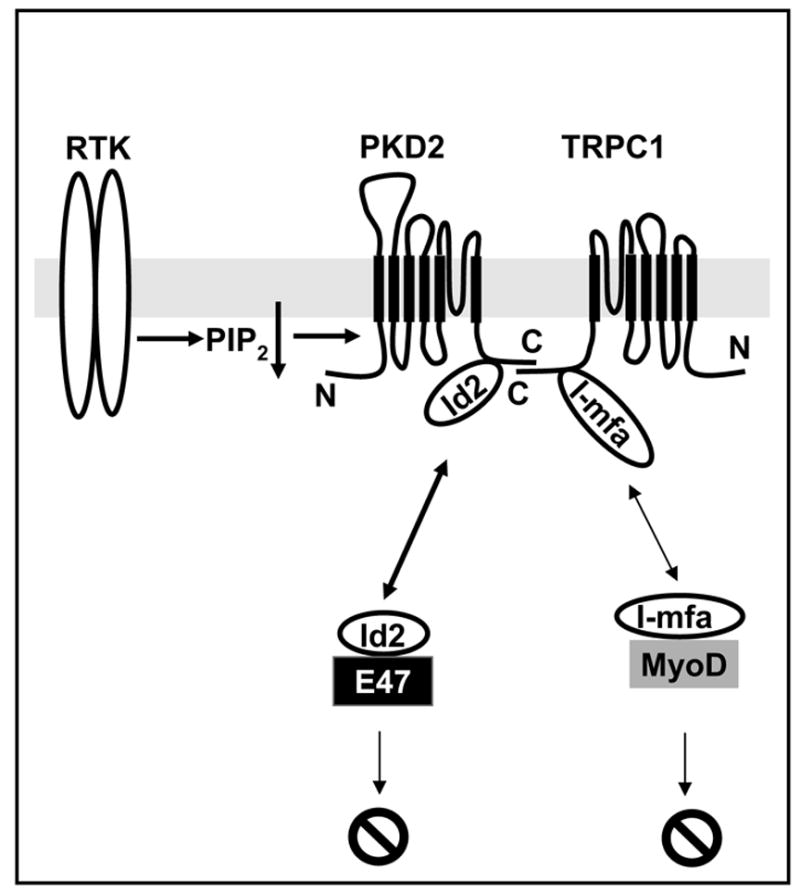

Traditionally, channel activation is considered to occur through gating (opening and closing) of the channel. Therefore, an activating agent would prolong opening and/or reduce closing of the channel. The mechanisms underlying PKD2 gating are currently unknown. However, it was recently reported that PKD2 activity was induced in response to EGFR stimulation in the LLC-PK1 cell line [36]. Ma et al [36] reasoned that PKD2 might be downstream of PLC activation as it was shown for the majority of TRP channels. Because numerous cell surface receptors are coupled to PLC, Ma et al [36] searched for mutations in known cell surface receptor systems that would lead to cyst formation in mice. Mice homozygous for the deletion of EGFR showed cystic dilatation in the collecting duct [72], an area that is mainly affected by mutations in pkd2 and in ADPKD patients [5, 6, 73]. Therefore, they tested whether EGF could activate PKD2. EGF did activate PKD2 through the activity of the γ2 isoform of PLC (PLC-γ2) and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K,) and this activation was independent of the depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores [36]. Pharmacological experiments indicated that reduction of PIP2 was responsible for the EGF-induced activation of PKD2 (Fig. 4). Consistently, infusion of purified PIP2 through the recording pipette suppressed the PKD2-mediated effect on EGF-induced conductance, while pipette infusion of phosphatidylinositol-3, 4, 5-trisphosphate (PIP3) had no effect on this conductance. Overexpression of type Iα phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase (PIP(5)Kα), which catalyzes the formation of PIP2, suppressed EGF-induced currents. The physiological relevance of this regulation was supported by loss-of-function experiments whereby, PKD2 knockdown by RNAi or overexpression of the PKD2 mutant, PKD2-D511V eliminated the EGF-induced currents in LLC-PK1 cells. Therefore this study showed that PKD2 was activated under physiological conditions and this activation was necessary for the increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration by EGF [36]. Given that EGFR deletion caused cystic dilatation, one could propose that impaired growth factor Ca2+ signaling could be the underlying cause of cyst formation, at least in type 2 ADPKD. The fact that EGFR knock out did not produce a phenotype as severe as in pkd2 knock out animals, it may simply imply that PKD2 may function downstream of other growth factors. However, there are several points that are worth discussing. First, overexpression of PKD2 did not increase EGF-induced whole cell currents more than 3-fold raising the question of whether PKD2 formed an EGF-activated channel by itself or induced the activity of an endogenous channel in response to EGF. While this question has not been formally addressed, there are several lines of evidence to suggest the former. In this regard, biochemical experiments have shown that only a small fraction of transfected PKD2 (>5%) reached the plasma membrane [36], in agreement with a previous report that native or transfected PKD2 could be barely detected in the plasma membrane of LLC-PK1 cells [24]. Therefore, the modest increase in whole cell currents in the Ma et al study [36] could simply reflect low presence of PKD2 in the plasma membrane. In this regard, it would be interesting to test whether co-expression of PKD2 with PKD1 and/or PIGEA-14 could enhance the EGF response in LLC-PK1 cells. Second, PKD2 overexpression resulted in the formation of a channel with high K+ permeability as it would be expected for PKD2 from previous studies including studies with purified PKD2 [31]. Third, pipette infusion of a PKD2-specific antibody which recognized a cytosolic region immediately following transmembarne segment 6 suppressed the EGF-induced currents [36]. Mutations in the putative pore forming region of PKD2 would be very informative in this regard. Nevertheless, from a cell biology point of view, Ma et al [36] showed that PKD2 channel activity produced by PKD2 either acting alone or in association with other subunits was necessary for EGF and perhaps other growth factor-induced Ca2+ signaling. This type of Ca2+ signaling could be responsible for long term effects on cellular phenotypes such as differentiation, proliferation, etc. Another point that could have implications in PKD2 gating was that EGF primarily increased the amplitude of the inward component of PKD2-dependent currents [36]. This appears to be at odds with the proposal that EGF activated PKD2 by releasing it from PIP2-mediated inhibition [36], as PIP2 would be expected to directly bind to the channel. Therefore, it is difficult to envision how PIP2 breakdown could occur more efficiently at negative versus positive potentials. New preliminary data (Bai, CX, S.K., Li, WP, and L.T. submitted) suggest the following scenario: PIP2 indirectly inhibits PKD2 by recruiting to the channel a protein that regulates PKD2 activity in a voltage-dependent fashion, that is to function as a negative regulator at negative potentials and an activator at positive potentials. The mechanism of PKD2 activation by EGF appears to be different from the mechanism by which EGF activated another TRP channel, TRPC5. In the case of TRPC5, EGF acted through Rac1 to induce the activation of PIP(5)Kα and production of PIP2, which in turn promoted the vesicular translocation of TRPC5 from intracellular compartments to the plasma membrane [74]. Ma et al [36] proposed that both mechanisms may be functional in PKD2. For example a global increase in PIP2 in response to EGFR activation through the Rac1/PIP(5)Kα pathway may be responsible for the translocation of PKD2-containing vesicles to the plasma membrane. However, local reduction of PIP2 may be required for the activation of PKD2 at the plasma membrane. A fraction of overexpressed PKD2 at the plasma membrane may escape inhibition by PIP2 and show constitutive activity. This can explain the lack of full activation of PKD2 by simply placing it in the plasma membrane through association with PKD1 or neutralization of S812 and possible escape from ER retention.

Fig. 4.

Hypothetical model of PKD2-mediated cell signaling. PKD2 physically associates with TRPC1 and can be activated by receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK) through the reduction of plasma membrane PIP2. PKD2 and TRPC1 associate with Id2 and I-mfa, respectively, which can bind and suppress the transcriptional activity of two distinct subsets of bHLHs, E47 and MyoD-related proteins.

Activation through PKD1

Following up on the work of Hanaoka et al [29], Delmas et al [35] confirmed that PKD1 promoted the targeting of PKD2 to the plasma membrane. Moreover, they showed that addition of a monoclonal antibody (MR3) against a portion of the extracellular domain of PKD1 (amino acid residues 2938 – 2956), which is in close proximity to a domain homologous to the receptor for egg jelly (REJ) further augmented the activity of the PKD1/PKD2 complex. Delmas et al [35] proposed that ligand binding to the REJ domain of PKD1 induced a conformational change in PKD1 which somehow resulted in PKD2 activation. Therefore, in addition to functioning as a chaperone, PKD1 may also function as a gate for PKD2. Interestingly, the PKD1-mediated gating of PKD2 was voltage independent [35]. In addition they found that PKD1 activation by the MR3 antibody activated the Gi/o subunits of G proteins. As a result, PKD1 stimulation could modulate cell signaling through two independent modes, activation of Ca2+ entry through PKD2 and also activation of G proteins. This report [35] was the first to show that PKD2 activation occurs through PKD1-mediated gating at the plasma membrane. However, whether such an activation mechanism is operational under physiological conditions remains to be elucidated. A subsequent study showed that antibody binding to another domain in the extracellular region of PKD1 resulted in channel inhibition [62]. Therefore, it also remains to be clarified how antibody binding to different domains in PKD1 results in such profound differences in the regulation of PKD2 activity.

Overall, PKD2 activation has been shown to be induced by EGF [36], binding to PKD1 [35], and/or intracellular Ca2+ [45]. Activation by EGF was described at the plasma membrane and is likely to also occur in the cilium because of the presence of some of the critical components there. It is, however, unknown whether it can occur in the ER. Gating and activation by PKD1 has been documented in the plasma membrane and it is likely to occur in the cilium because of the presence of PKD1 in the cilium [62], and the lack of the fluid flow response in cells lacking PKD1 or PKD2 [62], if PKD1 and PKD2 work together as mechanotransducers. However, it is unknown whether this mode of activation could be operative in PKD2 residing in the ER. In fact, it was shown that PKD2 reduced the plasma membrane expression of PKD1 by sequestering it in the ER [75]. However, the function of PKD1 complexed with PKD2 in the ER is unknown. Finally, the role of intracellular Ca2+ in the activation mechanism of PKD2 is very interesting as it may represent a universal mode of PKD2 activation and has been shown in other TRP channels [76]. However, it is currently unknown how this regulation occurs and what determines specificity. For example, will any type of intracellular Ca2+ rise be sufficient to induce PKD2 activity, or this activation occurs indirectly through a currently unknown Ca2+-binding protein?

PKD2-mediated signal transduction

While all the above described functions of PKD2 in these discrete subcellular locales may represent true physiological functions, the mechanism by which mutations in PKD2 result in ADPKD is currently unknown. What is the most meaningful system to study PKD2-mediated signal transduction in regard to ADPKD pathophysiology? This would be a difficult task to address in cell culture studies. If PKD1 and PKD2 function as mechano- and/or chemosensors in the cilium, it would be difficult to faithfully recapitulate their function in cell culture unless the activating mechanisms are known and the appropriate cell type is used. Loss of cilium is not intrinsically coupled to the cell cycle and the final outcome can differ from cell type to cell type. For example, deletion of the outer dense finer 2 gene (odf2) in mouse F9 embryonic carcinoma cells resulted in loss of cilia without a measurable effect on cell cycle progression [77]. The same was true for Dsas-4 [71] and AKAP450 [70] in Drosophila. Therefore, deletion of PKD1, PKD2 or even components of the intraflagellar transport (IFT) machinery may not result in increased proliferation in cell culture as would be expected for a typical cystogene.

A good starting point to address the physiological relevance of native PKD2 in cell culture could be the pathogenic PKD2-D511V mutation which clearly indicates that loss of channel activity per se is the cause of type 2 and possibly type 1, ADPKD. This assessment cannot be made with truncation mutants because they impair not only channel activity but also by interacting with other proteins such as PKD1, TRPC1, etc. Therefore, based on these mutants, it is not clear whether mutations in PKD2 result in ADPKD because of loss of channel activity or loss of protein-protein interactions. In contrast, the PKD2-D511V mutation, which has not only been described at the genomic level but also at the mRNA level [78], does not affect the expression, subcellular targeting, or protein-protein interactions but only channel activity [36, 46]. Then, what are consequences of impaired PKD2 channel activity in ADPKD? The answer is unknown. However, if we assume that the primary defect in type 2 ADPKD is PKD2-mediated Ca2+ influx (and not Na+ or K+ which also pass through PKD2), it is possible that a connection between a Ca2+ channel and cAMP can be made. It has been reported that cystic cells have abnormally high levels of cAMP [79–82] and the administration of a vasopressin V2 receptor antagonist, which reduced cAMP, suppressed the cystic phenotype in PKD2 knock out mice [83] and other animal models [84, 85]. It is also known that store-operated Ca2+ channels are directly coupled to specific isoforms of adenylyl cyclases [86–88]. It is therefore, tempting to speculate that somehow PKD2-mediated Ca2+ entry may be directly coupled to the production of cAMP. However, this connection has not been made yet. Examples of a modulatory role of PKD2 in PKD1-mediated cell signaling have been shown [89, 90] but a direct role of PKD2 channel activity in these models is unknown.

In regard to PKD2-mediated signal transduction and its relevance to ADPKD, it was recently shown that PKD2 regulates cell proliferation through a physical interaction with Id2 [91], a known inhibitor of the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors. Binding of Id2 to the C-terminal cytosolic tail of PKD2 resulted in the cytosolic sequestration of Id2 and upregulation of the activity of the cell cycle regulator, p21, resulting in reduction of proliferation through the downregulation of cyclin-E and CDK2 activities (Fig. 4). PKD1 overexpression somehow enhanced the phosphorylation state of PKD2 and subsequently increased binding of PKD2 to Id2. Therefore, Li et al [46] proposed that naturally occurring mutations in PKD2 would result in insufficient cytosolic sequestration of Id2 and subsequent increase in nuclear import of Id2. Similarly, PKD1 mutations would enhance the nuclear translocation of Id2 by reducing the phosphorylation state of PKD2 and thereby allowing Id2 to travel to the nucleus. This increased expression of Id2 in the nucleus was shown to result in increased proliferation in cells harboring pathogenic mutations of PKD2 and/or PKD1. These data appear to provide an attractive mechanistic model by which mutations in PKD1 and/or PKD2 may result in increased proliferation, which is traditionally considered as one of the hallmarks of cyst formation. However, it is not immediately obvious how this model can explain disease pathogenesis of PKD2-D511V and possibly other missense mutations that do not alter the Id2 binding site. In addition, it is unknown whether Id2 is mislocalized in cysts derived from PKD2 null mice, how PKD1 enhances phosphorylation of PKD2 since it does not possess intrinsic kinase activity, and more importantly what is the role of the cilium in this pathway. While future work will clarify these questions, the present data support a model by which a TRP channel functionally interacts with a regulator of the bHLH family of transcription factors (Fig. 4). This concept was originally proposed by Ma et al [92]. In this study, a yeast two hybrid screen using the C-terminal cytosolic fragment of TRPC1, an interacting protein with PKD2 [11], resulted in the identification of the “a” isoform of the myogenic family (I-mfa). I-mfa is a known inhibitor of a subset of bHLHs such as myogenin [93], MyoD [93], and other bHLHs [94]. Interestingly, I-mfa does not inhibit the function of the E47 subset of bHLHs [93, 94]. Therefore, it is quite intriguing that two independent unbiased screens [46, 92] using the C-termini of structurally related and interacting channels identified two structurally unrelated proteins with complementary functions. The data clearly indicate the existence of a novel signal transduction pathway linking TRP ion channel and bHLH functional regulation (Fig. 4).

Conclusions

Research in the area of PKD2 cell biology in the past several years has been marked by the discovery of the primary cilium as a relevant organelle to ADPKD pathophysiology and the functional characterization of PKD2 channel in cellular and cell-free systems. The recent discovery of reciprocal interactions between TRP channels and regulators of bHLH transcription factors along with a role of PKD2 in growth factor-operated Ca2+ entry, points to a new signal transduction pathway linking receptor-operated Ca2+ entry and transctiptional regulation through bHLHs (Fig. 4). The challenge in the future would be to identify the key players and molecular mechanisms underlying this pathway. This would entail an understanding of the structure-function relationship of PKD2, its mechanisms of cellular trafficking, gating and activation, and the role of the primary cilium in this pathway. We foresee exciting times for PKD2 cell biology.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Patrick Delmas, Chang-Xi Bai, and Takis Pantazis for comments on the manuscript. Research on PKD2 and TRPC1 in the laboratory of LT was supported by the Polycystic Kidney Disease Foundation, John S. Gammill Endowed Chair in Polycystic Kidney Disease, Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology, and NIH (DK59599).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mochizuki T, Wu G, Hayashi T, Xenophontos SL, Veldhuisen B, Saris JJ, Reynolds DM, Cai Y, Gabow PA, Pierides A, Kimberling WJ, Breuning MH, Deltas CC, Peters DJ, Somlo S. Science. 1996;272(5266):1339–1342. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5266.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes J, Ward CJ, Peral B, Aspinwall R, Clark K, San Millan JL, Gamble V, Harris PC. Nat Genet. 1995;10(2):151–160. doi: 10.1038/ng0695-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Consortium EPKD. Cell. 1994;77(6):881–894. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Consortium IPKD. Cell. 1995;81(2):289–298. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90339-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gabow PA. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(5):332–342. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307293290508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grantham JJ. Am J Kidney Dis. 1996;28(6):788–803. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(96)90378-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson PD. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(2):151–164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnaout MA. Annu Rev Med. 2001;52:93–123. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.52.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boletta A, Germino GG. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13(9):484–492. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Igarashi P, Somlo S. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13(9):2384–2398. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000028643.17901.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsiokas L, Arnould T, Zhu C, Kim E, Walz G, Sukhatme VP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(7):3934–3939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montell C, Birnbaumer L, Flockerzi V. Cell. 2002;108(5):595–598. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00670-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramsey IS, Delling M, Clapham DE. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:619–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040204.100431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clapham DE. Nature. 2003;426(6966):517–524. doi: 10.1038/nature02196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Owsianik G, Talavera K, Voets T, Nilius B. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:685–717. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040204.101406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turner H, Fleig A, Stokes A, Kinet JP, Penner R. Biochem J. 2003;371(Pt 2):341–350. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vergarajauregui S, Puertollano R. Traffic. 2006;7(3):337–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00387.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Venkatachalam K, Hofmann T, Montell C. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(25):17517–17527. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600807200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miedel MT, Weixel KM, Bruns JR, Traub LM, Weisz OA. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(18):12751–12759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511104200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teilmann SC, Byskov AG, Pedersen PA, Wheatley DN, Pazour GJ, Christensen ST. Mol Reprod Dev. 2005;71(4):444–452. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shin JB, Adams D, Paukert M, Siba M, Sidi S, Levin M, Gillespie PG, Grunder S. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(35):12572–12577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502403102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raychowdhury MK, McLaughlin M, Ramos AJ, Montalbetti N, Bouley R, Ausiello DA, Cantiello HF. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(41):34718–34722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507793200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheffers MS, Le H, van der Bent P, Leonhard W, Prins F, Spruit L, Breuning MH, de Heer E, Peters DJ. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11(1):59–67. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo Y, Vassilev PM, Li X, Kawanabe Y, Zhou J. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(7):2600–2607. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.7.2600-2607.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cai Y, Maeda Y, Cedzich A, Torres VE, Wu G, Hayashi T, Mochizuki T, Park JH, Witzgall R, Somlo S. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(40):28557–28565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pazour GJ, San Agustin JT, Follit JA, Rosenbaum JL, Witman GB. Curr Biol. 2002;12(11):R378–380. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00877-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jurczyk A, Gromley A, Redick S, San Agustin J, Witman G, Pazour GJ, Peters DJ, Doxsey S. J Cell Biol. 2004;166(5):637–643. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200405023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rundle DR, Gorbsky G, Tsiokas L. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(28):29728–29739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400544200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanaoka K, Qian F, Boletta A, Bhunia AK, Piontek K, Tsiokas L, Sukhatme VP, Guggino WB, Germino GG. Nature. 2000;408(6815):990–994. doi: 10.1038/35050128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen XZ, Vassilev PM, Basora N, Peng JB, Nomura H, Segal Y, Brown EM, Reeders ST, Hediger MA, Zhou J. Nature. 1999;401(6751):383–386. doi: 10.1038/43907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gonzalez-Perrett S, Kim K, Ibarra C, Damiano AE, Zotta E, Batelli M, Harris PC, Reisin IL, Arnaout MA, Cantiello HF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(3):1182–1187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vassilev PM, Guo L, Chen XZ, Segal Y, Peng JB, Basora N, Babakhanlou H, Cruger G, Kanazirska M, Ye C, Brown EM, Hediger MA, Zhou J. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;282(1):341–350. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pelucchi B, Aguiari G, Pignatelli A, Manzati E, Witzgall R, Del Senno L, Belluzzi O. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(2):388–397. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004121146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cantiello HF. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286(6):F1012–1029. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00181.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delmas P, Nauli SM, Li X, Coste B, Osorio N, Crest M, Brown DA, Zhou J. FASEB J. 2004;18(6):740–742. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0319fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma R, Li WP, Rundle D, Kong J, Akbarali HI, Tsiokas L. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(18):8285–8298. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.18.8285-8298.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hidaka S, Konecke V, Osten L, Witzgall R. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(33):35009–35016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314206200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kottgen M, Benzing T, Simmen T, Tauber R, Buchholz B, Feliciangeli S, Huber TB, Schermer B, Kramer-Zucker A, Hopker K, Simmen KC, Tschucke CC, Sandford R, Kim E, Thomas G, Walz G. EMBO J. 2005;24(4):705–716. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Streets AJ, Moon DJ, Kane ME, Obara T, Ong AC. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15(9):1465–1473. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Newby LJ, Streets AJ, Zhao Y, Harris PC, Ward CJ, Ong AC. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(23):20763–20773. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107788200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsiokas L, Kim E, Arnould T, Sukhatme VP, Walz G. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(13):6965–6970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qian F, Germino FJ, Cai Y, Zhang X, Somlo S, Germino GG. Nat Genet. 1997;16(2):179–183. doi: 10.1038/ng0697-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kottgen M, Walz G. Pflugers Arch. 2005;451(1):286–293. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1417-3. Epub 2005 May 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen XZ, Segal Y, Basora N, Guo L, Peng JB, Babakhanlou H, Vassilev PM, Brown EM, Hediger MA, Zhou J. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;282(5):1251–1256. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koulen P, Cai Y, Geng L, Maeda Y, Nishimura S, Witzgall R, Ehrlich BE, Somlo S. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4(3):191–197. doi: 10.1038/ncb754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Y, Wright JM, Qian F, Germino GG, Guggino WB. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(50):41298–41306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510082200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qian Q, Hunter LW, Li M, Marin-Padilla M, Prakash YS, Somlo S, Harris PC, Torres VE, Sieck GC. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12(15):1875–1880. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aguiari G, Banzi M, Gessi S, Cai Y, Zeggio E, Manzati E, Piva R, Lambertini E, Ferrari L, Peters DJ, Lanza F, Harris PC, Borea PA, Somlo S, Del Senno L. FASEB J. 2004;18(7):884–886. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0687fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hagiwara H, Ohwada N, Takata K. Int Rev Cytol. 2004;234:101–141. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(04)34003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Q, Taulman PD, Yoder BK. Physiology (Bethesda) 2004;19:225–230. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00003.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davenport JR, Yoder BK. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289(6):F1159–1169. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00118.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Snell WJ, Pan J, Wang Q. Cell. 2004;117(6):693–697. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pazour GJ, Witman GB. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15(1):105–110. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Praetorius HA, Spring KR. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2003;12(5):517–520. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200309000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Praetorius HA, Spring KR. J Membr Biol. 2001;184(1):71–79. doi: 10.1007/s00232-001-0075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Praetorius HA, Spring KR. J Membr Biol. 2003;191(1):69–76. doi: 10.1007/s00232-002-1042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Praetorius HA, Frokiaer J, Nielsen S, Spring KR. J Membr Biol. 2003;191(3):193–200. doi: 10.1007/s00232-002-1055-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yoder BK, Hou X, Guay-Woodford LM. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13(10):2508–2516. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000029587.47950.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Geng L, Okuhara D, Yu Z, Tian X, Cai Y, Shibazaki S, Somlo S. J Cell Sci. 2006;119(Pt 7):1383–1395. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Karcher C, Fischer A, Schweickert A, Bitzer E, Horie S, Witzgall R, Blum M. Differentiation. 2005;73(8):425–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2005.00048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McGrath J, Somlo S, Makova S, Tian X, Brueckner M. Cell. 2003;114(1):61–73. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00511-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nauli SM, Alenghat FJ, Luo Y, Williams E, Vassilev P, Li X, Elia AE, Lu W, Brown EM, Quinn SJ, Ingber DE, Zhou J. Nat Genet. 2003;33(2):129–137. doi: 10.1038/ng1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Qin H, Burnette DT, Bae YK, Forscher P, Barr MM, Rosenbaum JL. Curr Biol. 2005;15(18):1695–1699. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Clapham DE. Cell. 1995;80(2):259–268. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90408-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pazour GJ, Agrin N, Leszyk J, Witman GB. J Cell Biol. 2005;170(1):103–113. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200504008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huangfu D, Liu A, Rakeman AS, Murcia NS, Niswander L, Anderson KV. Nature. 2003;426(6962):83–87. doi: 10.1038/nature02061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Corbit KC, Aanstad P, Singla V, Norman AR, Stainier DY, Reiter JF. Nature. 2005;437(7061):1018–1021. doi: 10.1038/nature04117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haycraft CJ, Banizs B, Aydin-Son Y, Zhang Q, Michaud EJ, Yoder BK. PLoS Genet. 2005;1(4):e53. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schneider L, Clement CA, Teilmann SC, Pazour GJ, Hoffmann EK, Satir P, Christensen ST. Curr Biol. 2005;15(20):1861–1866. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Martinez-Campos M, Basto R, Baker J, Kernan M, Raff JW. J Cell Biol. 2004;165(5):673–683. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200402130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Basto R, Lau J, Vinogradova T, Gardiol A, Woods CG, Khodjakov A, Raff JW. Cell. 2006;125(7):1375–1386. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Threadgill DW, Dlugosz AA, Hansen LA, Tennenbaum T, Lichti U, Yee D, LaMantia C, Mourton T, Herrup K, Harris RC, et al. Science. 1995;269(5221):230–234. doi: 10.1126/science.7618084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wu G, D'Agati V, Cai Y, Markowitz G, Park J-H, Reynolds DM, Maeda Y, Le TC, Hou HJ, Kucherlapati R, Edelmann W, Somlo S. Cell. 1998;93:177–188. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81570-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bezzerides VJ, Ramsey IS, Kotecha S, Greka A, Clapham DE. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6(8):709–720. doi: 10.1038/ncb1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Grimm DH, Cai Y, Chauvet V, Rajendran V, Zeltner R, Geng L, Avner ED, Sweeney W, Somlo S, Caplan MJ. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(38):36786–36793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306536200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nilius B, Mahieu F. Mol Cell. 2006;22(3):297–307. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ishikawa H, Kubo A, Tsukita S. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7(5):517–524. doi: 10.1038/ncb1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Reynolds DM, Hayashi T, Cai Y, Veldhuisen B, Watnick TJ, Lens XM, Mochizuki T, Qian F, Maeda Y, Li L, Fossdal R, Coto E, Wu G, Breuning MH, Germino GG, Peters DJ, Somlo S. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10(11):2342–2351. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V10112342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yamaguchi T, Nagao S, Kasahara M, Takahashi H, Grantham JJ. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;30(5):703–709. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90496-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mangoo-Karim R, Uchic M, Lechene C, Grantham JJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86(15):6007–6011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.6007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yamaguchi T, Pelling JC, Ramaswamy NT, Eppler JW, Wallace DP, Nagao S, Rome LA, Sullivan LP, Grantham JJ. Kidney Int. 2000;57(4):1460–1471. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sullivan LP, Wallace DP, Grantham JJ. Physiol Rev. 1998;78(4):1165–1191. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.4.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Torres VE, Wang X, Qian Q, Somlo S, Harris PC, Gattone VH., 2nd Nat Med. 2004;10(4):363–364. doi: 10.1038/nm1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wang X, Gattone V, 2nd, Harris PC, Torres VE. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(4):846–851. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004121090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gattone VH, 2nd, Wang X, Harris PC, Torres VE. Nat Med. 2003;9(10):1323–1326. doi: 10.1038/nm935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chiono M, Mahey R, Tate G, Cooper DM. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(3):1149–1155. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.3.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cooper DM, Yoshimura M, Zhang Y, Chiono M, Mahey R. Biochem J. 1994;297(Pt 3):437–440. doi: 10.1042/bj2970437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fagan KA, Mons N, Cooper DM. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(15):9297–9305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.9297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bhunia AK, Piontek K, Boletta A, Liu L, Qian F, Xu PN, Germino FJ, Germino GG. Cell. 2002;109(2):157–168. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00716-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chauvet V, Tian X, Husson H, Grimm DH, Wang T, Hiesberger T, Igarashi P, Bennett AM, Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O, Somlo S, Caplan MJ. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(10):1433–1443. doi: 10.1172/JCI21753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Li X, Luo Y, Starremans PG, McNamara CA, Pei Y, Zhou J. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7(12):1102–1112. doi: 10.1038/ncb1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ma R, Rundle D, Jacks J, Koch M, Downs T, Tsiokas L. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(52):52763–52772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309610200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chen CM, Kraut N, Groudine M, Weintraub H. Cell. 1996;86(5):731–741. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kraut N, Snider L, Chen CM, Tapscott SJ, Groudine M. Embo J. 1998;17(21):6276–6288. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.21.6276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]