Abstract

It has been proposed that abnormal vibrissae input to the motor cortex (M1) mediates short-term cortical reorganization after facial nerve lesion. To test this hypothesis, we cut first the infraorbital nerve (ION cut) and then the facial nerve (VII cut) in order to evaluate M1 reorganization without any aberrant, facial-nerve-lesion-induced sensory feedback. In each animal, M1 output was assessed in both hemispheres by mapping movements induced by intracortical microstimulation. M1 output was compared in different types of peripheral manipulations: (i) contralateral intact vibrissal pad (intact hemispheres), (ii) contralateral VII cut (VII hemispheres), (iii) contralateral ION cut (ION hemispheres), (iv) contralateral VII cut after contralateral ION cut (ION + VII hemispheres), (v) contralateral pad botulinum-toxin-injected after ION cut (ION + BTX hemispheres). Right and left hemispheres in untouched animals were the reference for normal M1 map (control hemispheres). Findings demonstrated that: (1) in ION hemispheres, the mean size of the vibrissae representation was not significantly different from those in intact and control hemispheres; (2) reorganization of the vibrissae movement representation clearly emerged only in hemispheres where the contralateral vibrissae pad had undergone motor output disconnection (VII cut hemispheres); (3) the persistent loss of vibrissae input did not change the M1 reorganization pattern during the first 48 h after motor paralysis (ION + VII cut and ION + BTX hemispheres). Thus, after motor paralysis, vibrissa input does not provide the gating signal necessary to trigger M1 reorganization.

The primary motor cortex (M1) of mammals shows an ordered representation of musculature or movements (Penfield & Rasmussen, 1950; Woolsey et al. 1952), and receives somatic sensory inputs closely aligned with the motor output (Asanuma et al. 1968; Rosèn & Asanuma, 1972; Wong et al. 1978; Sievert & Neafsey, 1986). Convergent experimental observations have shown considerable plasticity of M1 movement representations in mammals (Sanes & Donoghue, 2000; Kaas, 2000). Orderly reshaping in the size and configuration of movement representations is a common feature of motor cortical maps after peripheral disconnection (Sanes et al. 1988, 1990; Toldi et al. 1996; Huntley, 1997a; Schieber & Deuel, 1997; Wu & Kaas, 1999; Franchi, 2000b, 2002; Qi et al. 2000). It has been suggested that the mechanism triggering M1 output reorganization could be an alteration in sensory input to M1 as a consequence of peripheral disconnection (Donoghue et al. 1990; Sanes et al. 1992). Indeed, both animal and human studies have shown that a reduction in sensory feedback can alter motor cortex excitability (Sanes et al. 1992; Brazil-Neto et al. 1993; Cohen et al. 1993; Ziemann et al. 1998; Franchi, 2001). It is presumed that after peripheral disconnection, decreased M1 excitability due to abnormal sensory feedback might be the early electrophysiological change that translates into structural plasticity.

After facial nerve transection in rats, forelimb, neck, eye and ipsilateral vibrissae movements occupy specific and orderly sites of the cortical region where the movement of the disconnected vibrissae is normally represented (Sanes et al. 1988, 1990; Toldi et al. 1996; Huntley, 1997a; Franchi, 2000b). After facial nerve transection, the vibrissae are atonically retropositioned, abnormally reducing the sensory input to M1. It has been proposed that the abnormal vibrissae input transmitted, via the infraorbital nerve, to the motor cortex mediates the short-term cortical reorganization after facial nerve lesion (Donoghue et al. 1990; Farkas et al. 1999, 2000; Krakauer & Ghez, 2000). To test this hypothesis we cut the infraorbital nerve, and then cut the facial nerve, the aim being to evaluate cortical reorganization without any aberrant, facial-nerve-lesion-induced sensory feedback. Differences in the M1 short-term reorganization after motor disconnection, with and without vibrissae sensory input, would support this hypothesis. In contrast, a lack of differences would demonstrate that selective vibrissae sensory feedback is not a sufficient stimulus to trigger M1 short-term reorganization.

Methods

Overview of the experimental plan

Experiments were carried out on 20 Albino rats, weighing 250–300 g. The experimental plan was designed according to the Italian law for care and use of experimental animals (DL116/92) and approved by the Italian Ministry of Health. For all experimental procedures rats were anaesthetized initially with ketamine hydrochloride (100 mg kg−1i.p.). For the duration of the experiment, anaesthesia was maintained by supplementary ketamine injections such that a long latency and sluggish hindlimb withdrawal was achieved only with severe pinching of the hindfoot. Under anaesthesia, the body temperature was maintained at 36–38°C with a heat lamp.

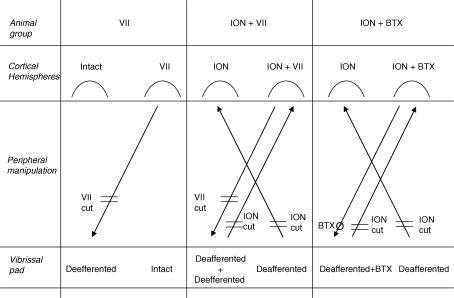

The experimental plan is illustrated in the Fig. 1. The general procedures were as follows. First, 10 animals underwent bilateral, irreversible vibrissae pad input disconnection by severing the infraorbital nerve (ION cut). We chose bilateral ION severing to ensure a complete vibrissae pad input disconnection, since a large percentage of neurons in the rat's sensory motor cortex receive bilateral sensory input (Armstrong-James & George, 1988). Previous studies have shown that 2 weeks of recovery provide ample time for modulatory influences on motor cortex reorganization (Sanes et al. 1988, 1990; Donoghue et al. 1990; Toldi et al. 1996; Franchi, 2001). Therefore, 2 weeks later, the same animals underwent unilateral vibrissae pad output disconnection. In a group of five animals the facial nerve (VII cut) of one side was severed (ION + VII group: ION hemispheres and ION + VII hemispheres), while the remaining five animals were given a botulinum toxin (BTX) injection into the vibrissal pad of one side (ION + BTX group: ION hemispheres and ION + BTX hemispheres). The reversible blockade of motor activity induced with BTX leads to short-term M1 reorganization comparable to that induced by facial nerve lesion (Franchi, 2002). The use of two different type of vibrissa output disconnection provides an internal control of input-deprived M1 short-term reorganization and ensures more confidence in the results. Second, another group of five animals underwent facial nerve severing of one side (VII group: intact hemispheres and VII hemispheres). For each animal, M1 mapping of both hemispheres was performed 48 h after facial nerve lesion and BTX injection. Finally, in five animals both hemispheres were mapped as reference for normal M1 mapping (control group: right and left control hemispheres). The control and experimental groups were matched for gender (three males for each group), age (13–15 weeks), weight (250–300 g at the time of mapping procedure) and side of the lesion.

Figure 1. Diagrams illustrating the experimental design and nomenclature.

Animals were divided into three experimental groups (animal group) and a control group (untouched animals, not shown). Peripheral manipulation: VII cut, facial nerve lesion at the exit from stilomastoid foramen; ION cut, infraorbital nerve lesion at the exit from infraorbital fissure. BTXØ, single injection of botulinum toxin at a single site in the vibrissa pad. Animal groups: VII, unilateral facial nerve lesion, 5 rats; ION + VII, bilateral infraorbital nerve lesion, followed by unilateral facial nerve lesion after 2 weeks, 5 rats; ION + BTX, bilateral infraorbital nerve lesion, followed by unilateral BTX injection after 2 weeks, 5 rats. Cortical hemispheres: intact, hemisphere contralateral to the intact vibrissa pad; VII, hemisphere contralateral to the deefferented vibrissa pad; ION, hemisphere contralateral to the deafferented vibrissa pad; ION + VII, hemisphere contralateral to the deafferented and deefferented vibrissa pad; ION + BTX hemisphere, hemisphere contralateral to the deafferented and BTX-injected pad.

Surgical procedures

All surgical procedures were performed under ketamine anaesthesia (100 mg kg−1i.p., and then supplemental doses i.m. as needed). In 10 animals, under the operating microscope, the infraorbital nerve of both sides was exposed, separated from its adjacent tissues and legated; then it was cut distally to eliminate all remaining fine branches. The proximal stump was dried and covered with acrylic tissue adhesive (Histoacryl) to prevent the proximal axons from sprouting. The skin was closed with 6-0 sutures and cleansed with an antibiotic solution. In the postoperative period none of the rats displayed complications such as self-mutilation, infection, or overt signs of discomfort. Clinical observation during natural whisking clearly showed that the deafferented vibrissa displayed bilateral rhythmical movements but did not suddenly retract when it hit against targets, as would normally be the case. After deafferentation the vibrissal pad proved unreactive to light pain-inducing sensory stimuli (i.e. light touching, squeezing or piercing). The loss of vibrissal pad sensitivity following deafferentation was clearly evidenced in all animals for the entire survival period (for more details see Franchi, 2001).

In five animals that underwent bilateral infraorbital nerve severing, and in five intact animals using surgical procedures similar to the above, the facial nerve of one side was exposed at the point where it exits the stilomastoid foramen, and transected just beyond the point of origin of the digastric nerve. Following facial nerve severing, the animals lacked vibrissae movement and blinking on the operated side (for more details see Franchi, 2000a, b).

In the remaining five animals that underwent bilateral infraorbital nerve severing, a single injection of BTX (8 u dissolved in 0.08 ml of saline; Botox; Allergan Sweepstakes Center, Ballsbridge, Dublin, Ireland) was delivered at a single site in the middle of the vibrissae pad of one side (for more details see Franchi, 2002). After BTX injection, the affected vibrissa lacked rhythmical movements during sniffing behaviour; they were also atonic and positioned backward.

Intracortical stimulation mapping

Intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) mapping was aimed at defining the extent of the vibrissa representation and the current threshold required to elicit vibrissa movements. The mapping procedure was similar to that described by Donoghue & Wise (1982) and Sanes et al. (1990), and detailed elsewhere (Franchi, 2000a). Briefly, the animals were placed in a Kopf stereotaxic apparatus and the frontal cortex was exposed by a large craniotomy. The dura remained intact, and was kept moist with a 0.9% saline solution. The electrode penetrations were regularly spaced out over a 500 μm grid. Alteration in the coordinate grid, up to 50 μm, was sometimes necessary to prevent the electrode from penetrating the surface blood vessels. These adjustments in the coordinate grid were not reported in the reconstruction maps. When adjustment exceeded 50 μm, penetration was not performed at this site. Glass insulated tungsten electrodes (0.6–1 MΩ impedance at 1 kHz) were used for stimulation. The electrode was lowered vertically to 1.5 mm below the cortical surface and adjusted ±200 μm so as to evoke movement at the lowest threshold. In a previous experiment this depth was found to correspond to layer V of the frontal agranular cortex (Franchi, 2000a). Cathodal monophasic pulses (30 ms train duration at 300 Hz, 200 μs pulse duration) of a maximum of 60 μA were passed through the electrode with a minimum interval of 2.5 s. Starting with a current of 60 μA, intensity was decreased in 5 μA steps until the movement was no longer evoked; then intensity was increased to a level at which nearly 50% of the stimulations elicited movement. This level defined the current threshold. If no movements or twitches were evoked with 60 μA, the site was recorded as negative (ineffective site). When movement was observed in two different body parts or bilateral vibrissa, current thresholds were determined for each component. In general, at threshold current levels, only one movement was elicited from any given point. Body parts activated by microstimulation were identified by visual inspection and/or muscle palpation. The terms ‘forelimb movement’ and ‘hindlimb movement’ refer collectively to distal and proximal joint movements. Forelimbs and hindlimbs were approximately half-way between flexion and extension and were alternately flexed and extended, particularly when defining representational borders.

Histology

At the end of the experimental procedure, the animals were perfused transcardially. The brains were sectioned and stained with thionine to verify microelectrode positions and depths.

In each animal, gross postperfusion examination of the injured nerves evidenced no nerve continuity at the acrylic stopper level. Under the operating microscope, care was taken to ensure that all ION fascicles had been tied and axotomized. In some animals a few axons had sprouted at the periphery of the acrylic stopper without clear reinnervation of distal vibrissal pad.

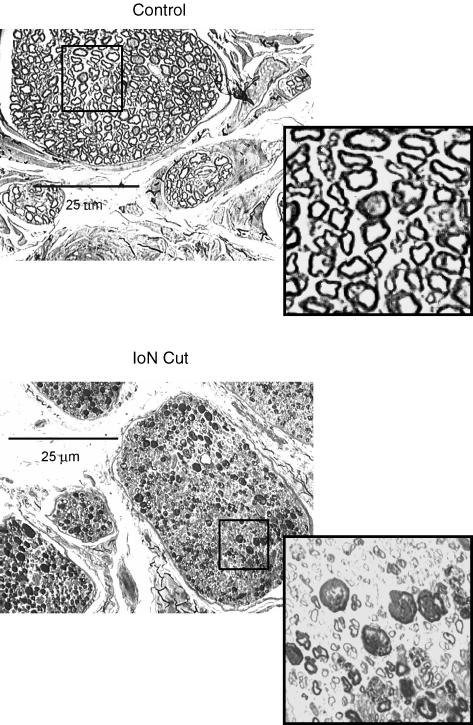

In all the animals studied, the exposed ION was cut proximal to the site of nerve injury and prepared for histological examination. After postfixation in osmium tetroxide, toluidine blue was used to stain sections that were 1 μm thick. Morphological examination of sections (Axioskop Zeiss and DMC Polaroid camera for image acquisition) showed extensive degenerative processes involving all axons proximal to the lesion (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Cross-section of the infraorbital nerve in a control, and proximal to the acrylic stopper 2 weeks postinjury.

Light photomicrograph (×200 magnification, osmium tetroxide and toluidine blue stain). Note evidence of Wallerian degeneration and/or perineural thickening in all ION fascicles (insert, ×1000 magnification).

Map construction and data analysis

Using a dedicated plotting program (written with the Laboratory View Development System, see Acknowledgements), an on-line grid map was constructed by labelling electrode penetrations according to the distance (in millimetres) from the bregma. At a current intensity of 60 μA or less, threshold values were recorded on a sheet scrolling below the map grid. This procedure considers the cortical surface subdivided into a square grid where each movement threshold point was the centre of a square that was 500 μm wide. In each hemisphere, vibrissa and forelimb movements were mapped in order to determine the extent and location of these representations. Penetrations were not performed in correspondence of large vessels and these sites were not taken into account in the computations. This procedure presents several potential sources of variability that could affect the accuracy of the configuration and size of movement representations. To reduce the effect of experimental sources of variability, similar mapping density was maintained across all animals. This procedure cannot prevent electrode track distortions arising from curvature in the lateral portion of the frontal cortex. This mainly affects the forelimb sites situated in the more lateral position in rat M1. Because the goal of this study was to document reorganization in that part of M1 where the electrode was lowered perpendicularly into the cortex, no attempt was made to correct for any potential distortion in the more lateral sites (Figs 3–6). The cortex medial to the vibrissa representation was not systematically explored less than 1 mm lateral from midline. In normal animals, the cortex medial to the vibrissa representation was occupied by a small representation of eye, eye–eyelid movements (Hall & Lindholm, 1974; Donoghue & Wise, 1982; Toldi et al. 1996; Guandalini, 1998) and by a thin strip of cortex where ICMS evoked miosis (Gioanni & Lamarche, 1985; Guandalini, 2001, 2003). In any case eye, eye–eyelid, pupilar movements and ineffective sites formed the basis for delineating the medial border of the vibrissa representation. The sample of eye, eye–eyelid and miosis sites in each hemisphere was too small and these sites have been collectively referred to as ‘eye sites’ (Figs 3–6).

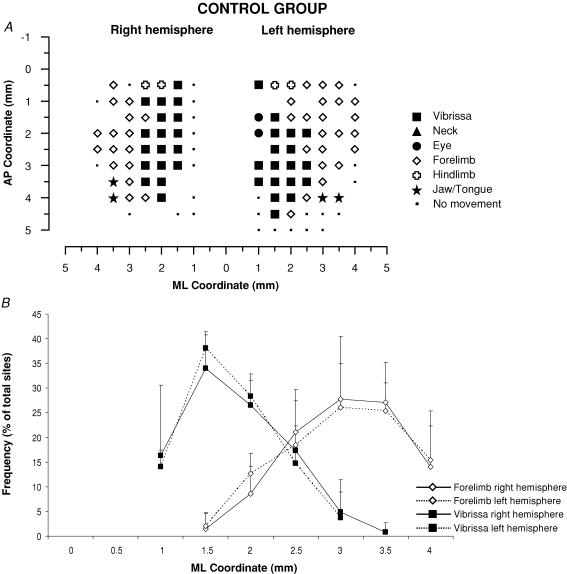

Figure 3. Surface view map and mediolateral distribution of movements in a control group.

A, example of representation of movements evoked at threshold current levels in the right and left hemispheres in control rats. The microelectrode was sequentially introduced to a depth of 1500 μm. Interpenetration distances were 500 μm. In these M1 mapping schemes, frontal poles are at the bottom. 0 corresponds to the bregma; numbers indicate rostral or caudal distance from the bregma or lateral distance from the midline. Movement evoked at one point is indicated by the following symbols: large filled square, contralateral vibrissae; open square, ipsilateral vibrissae; open diamond, forelimb; open cross, hindlimb; filled triangle, neck-upper trunk; filled star, jaw–tongue; filled circle, eye; small filled square, sites unresponsive at 60 μA; no symbol (within or at the border of the maps), penetration not performed due to presence of a large vessel. B, the mediolateral frequency distribution of penetrations eliciting vibrissa (filled square) and forelimb (open diamonds) movements in the right (continuous line) and left hemispheres (dashed line) of the control rats. For each hemisphere, penetrations were distributed into 0.5 mm bins extending from the midline (0 mm) to 4 mm lateral of the midline, irrespective of the anteroposterior coordinate. The number of penetrations falling into each bin was tailed and expressed as a percentage of the total number of penetrations for that movement (+ s.d.). Note that the vibrissa movement sites at 3 and 3.5 mm of mediolateral coordinate do not appear in the example of bilateral map shown above.

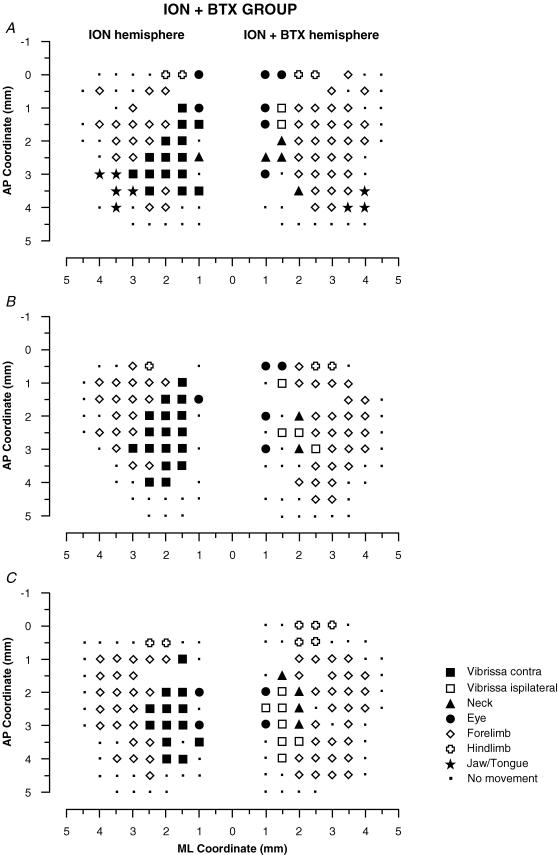

Figure 6. Surface view maps in a ION + BTX group.

Examples of bilateral vibrissa maps from three rats (A, B and C) showing one hemisphere with the contralateral vibrissae pad ION-cut-deafferented (ION hemisphere) and the other with the BTX-induced paralysis after ION cut in the contralatera vibrissa pad (ION + BTX hemisphere). The pattern of represented movement in the ION hemispheres showed a large contralateral vibrissa movement representation similar to that found in the ION hemispheres in the Fig. 5 and in the intact hemispheres in the Fig. 4. Also note that, in the ION + BTX hemispheres, the pattern of represented movements was qualitatively similar to that found in the VII hemispheres in the Fig. 4 and in the ION + VII hemispheres in the Fig. 5.

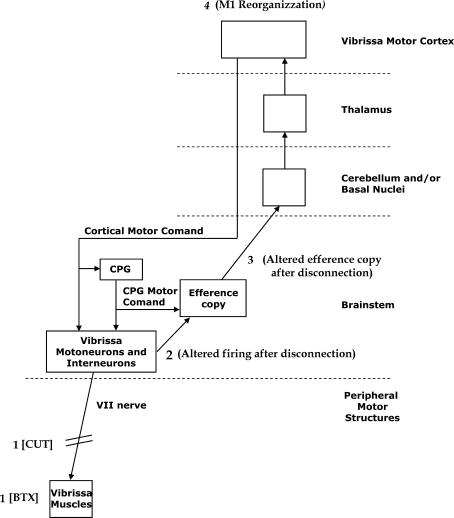

To quantitatively assess the changes in movement representation we compared the percentage of unresponsive and movement sites, expressed as a fraction of the number of sites from 1 to 2.5 mm to the midline, in all six groups of hemispheres (Fig. 7). This cut-off is applied because, in control hemispheres, 2.5 mm to the midline corresponded to the lateral-most significant point of vibrissae site distribution as evidenced in the Fig. 3A and B. To avoid interindividual biases related to differences in the size and mediolateral position of the motor map, unresponsive points situated around the map were not taken into account in the plotting frequency histograms (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Percentage of unresponsive and effective sites devoted to various movements in each of the group of hemispheres studied.

Across-group comparisons were made of unresponsive and effective sites devoted to various movements represented in M1 (up to 2.5 mm from the midline) for all hemispheres: control, intact, ION, VII, ION + VII, ION + BTX. Contralateral vibrissa movement is absent in deeferented groups and ipsilateral vibrissa movement is absent in the intact and ION hemispheres. In comparison with control and intact hemispheres, the ION hemisphere showed no significant difference in the percentage of unresponsive sites (A) or in the percentage of movement sites (B–F). In contrast, in comparison with control and intact hemispheres, the percentage of unresponsive sites (A), ipsilateral vibrissae (C), neck (D) and forelimb sites (E) was significantly increased in the VII, ION + VII and ION + BTX hemispheres. Comparison between the VII, ION + VII and ION + BTX hemispheres showed no significant difference in the percentage of unresponsive sites (A) or in the percentage of movement sites (B–F). Data are means + s.d. *Statistically significant differences between control versus ION, VII, ION + VII and ION + BTX hemispheres using the post hoc Scheffé test (S20.05;4,30 > 10.76; P < 0.05).The percentage of hindlimb movement sites is not reported because this movement was not extensively explored.

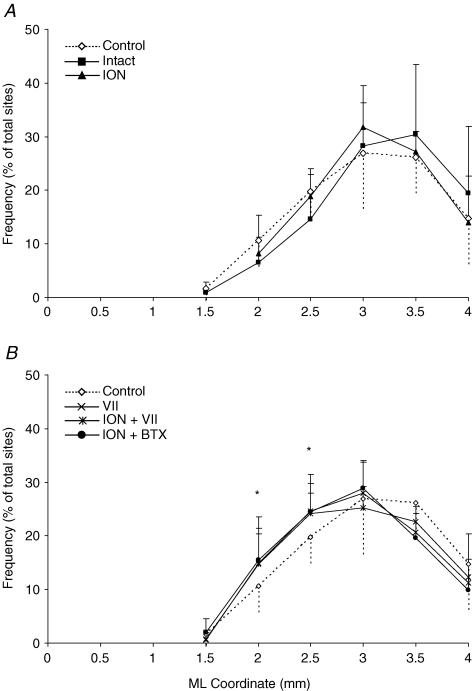

There is previous evidence that the forelimb representation shares the longest common border with the vibrissa representation, and that the position of the forelimb-vibrissa border can change under a variety of peripheral manipulations (Donoghue et al. 1990; Sanes et al. 1990). In light of this, for each group of hemispheres, a quantitative evaluation of mediolateral MI configuration was obtained by comparing mediolateral frequency distribution of sites eliciting vibrissa and forelimb movements versus distance from the midline (see Results and Fig. 8). To this end, in each hemisphere, penetrations were divided into 0.5-mm-wide bins into which all sites eliciting movement were grouped, irrespective of their anteroposterior coordinates. For each bin – starting 1 mm from the midline and extending 4.5 mm laterally – the number of vibrissa and forelimb sites were tallied and converted to frequency by expressing data as percentages of the total number of sites for each movement.

Figure 8. Distribution of forelimb movement sites in each of the group of hemispheres studied.

Comparison of mediolateral frequency distribution of penetration eliciting forelimb movement between the control and the intact and ION hemispheres (A) and between the control and the VII, ION + VII and ION + BTX hemispheres (B). The mediolateral position of the forelimb sites was distributed in 0.5 mm bins extending from the midline to 4 mm lateral, irrespective of the anteroposterior coordinate. The number of sites at each bin was expressed as a percentage of the total forelimb sites. Note that, in the ION hemispheres, the percentage of 2 and 2.5 mm mediolateral coordinate sites overlap those of the control (A, P > 0.05, χ2 test); in contrast, at the same sites, the percentage was significantly increased in the VII, ION + VII, and ION + BTX hemispheres (B, P < 0.05, χ2 test). There is no difference in the frequency distribution between VII, ION + VII and ION + BTX hemispheres (P > 0.05, χ2 test). *Statistically significant differences between control versus VII, ION + VII and ION + BTX hemispheres using the χ2 test.

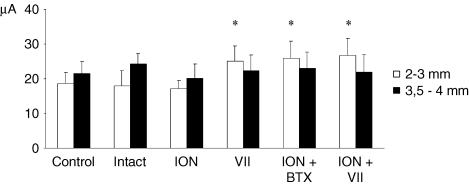

To determine whether any changes in representational movements were related to changes in movement-evoking thresholds, the thresholds for each movement were determined for each group of hemispheres (Fig. 9). For each group of hemispheres, a finer threshold analysis of the forelimb movement sites that emerged within the disconnected vibrissa region was obtained by comparing mediolateral threshold distribution (Figs 10 and 11).

Figure 9. Threshold current level for eliciting forelimb movement in each of the group of hemispheres studied.

In each group, the filled bar shows the threshold of forelimb sites situated 3.5–4 mm lateral to the midline (P = 0.94, ANOVA) and the open bar shows the threshold of forelimb sites 2–3 mm lateral (P < 0.0001, ANOVA). After vibrissae motor disconnection (VII, ION + VII and ION + BTX hemispheres) the threshold value increases only in the left bar containing the threshold current required to elicit the novel forelimb movement from the former vibrissae representation. There is no difference in the left bar value between control, intact and ION hemispheres (P > 0.05 Scheffé test) and between the VII, ION + VII and ION + BTX hemispheres (P > 0.05 Scheffé test). This evidence shows that the vibrissae input did not affect site excitability in the reorganizing portion motor cortex where novel forelimb movement emerges. *P < 0.05, Scheffé test: control, intact, ION versus VII, ION + BTX, ION + VII.

Figure 10. Distribution of thresholds for forelimb movement in each of the group of hemispheres studied.

Mediolateral distribution of thresholds for forelimb movements: comparison of control versus intact and ION hemispheres (A) and of control versus VII, ION + VII and ION + BTX hemispheres (B). Thresholds were grouped according to their distance from the midline irrespective of the anteroposterior coordinate. The numbers above the graph lines (B) indicate the statistical probability derived by group comparison (ANOVA). This graph shows: (i) in the ION hemispheres the threshold values overlap with the values for the control and intact hemispheres throughout the mediolateral coordinate; (ii) in all three deefferented hemispheres (B) at 3, 2.5 and 2 mm laterally, the threshold value is higher than in control hemispheres and increases progressively; threshold values in the other more lateral sites overlap with those of the control hemispheres. In each mediolateral coordinate, the mean threshold value is reported only when the mean value was obtained in 5 animals for each group.

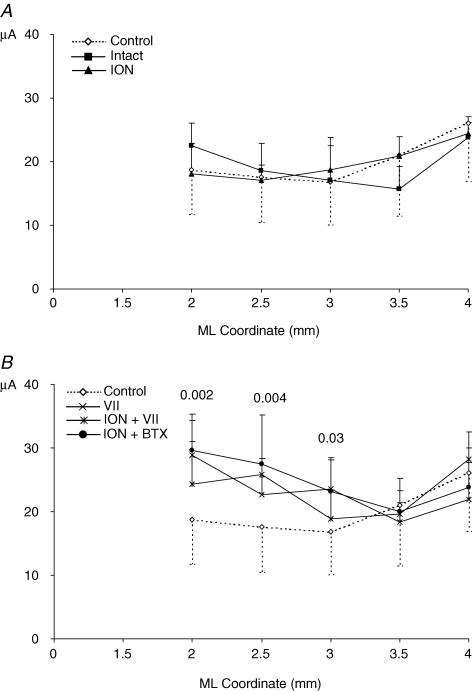

Figure 11. The proposed mechanisms of short-term reorganization of input-deprived motor vibrissa representation following motor disconnection.

The facial nucleus motor neurons and interneurons receive cortical motor commands and central pattern generator (CPG) motor commands. A copy of the motor command, that is, an efference copy, ascends from the brainstem to the vibrissa motor cortex (further explanations in the Discussion). The vibrissa motor disconnection by VII cut or BTX injection (1) might induce changes in the firing of facial nucleus motor neurons and interneurons (2) that might change the efference copy ascending to the motor cortex (3) that might trigger M1 reorganization (4).

Within-group comparisons were determined using paired t test. Across-group comparisons were determined using one-way ANOVA, and Scheffé's post hoc and χ2 tests. The χ2 test was presented using a two- or five-way contingency table (2 × 2 or 5 × 2). In the table, the rows refer to the animal group, and the columns to the frequency of movement sites medial and lateral to 2.5 mm of the medial-lateral coordinate. This point corresponded to the overlap point of the vibrissa and forelimb sites medial-lateral frequency distribution in the control group (see Fig. 1B). A probability value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The mean number of penetrations required to explore the motor region corresponding to the vibrissa and forelimb representations in each hemisphere on this 500 μm sampling grain was 69.4 ± 6. Both hemispheres in each rat were studied and a threshold-evoked movement map was derived from each hemisphere (Figs 3–5). In the presentation of results, we first evaluate interhemispheric variation in the motor map using data from the Control group. Next, we present results testing three related hypotheses: 1- the loss of an infraorbital nerve signal induces motor cortex plasticity; 2- the infraorbital nerve carries a signal that induces motor cortex plasticity; 3- the infraorbital nerve signal is irrelevant for motor cortex reorganization following vibrissa muscle paralysis.

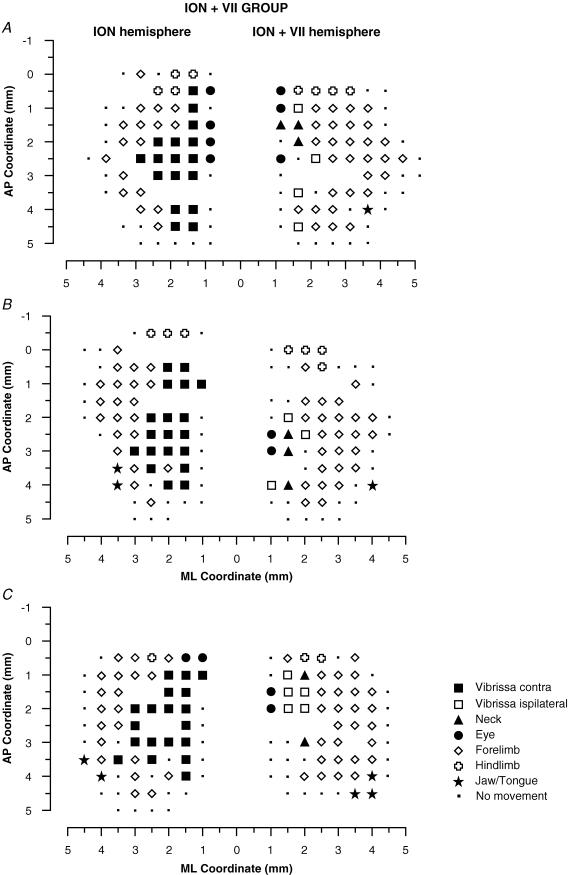

Figure 5. Surface view maps in a ION + VII group.

Examples of bilateral vibrissa maps from three rats (A, B and C) showing one hemisphere with the contralateral vibrissae pad ION-cut-deafferented (ION hemisphere) and the other with contralateral VII-cut-induced paralysis after vibrissae pad ION-cut-deafferented (ION + VII hemisphere). ION hemispheres evidenced a large contralateral vibrissa movement representation similar to that found in the intact hemispheres in the Fig. 3. Also note that the pattern of represented movements in the ION + VII hemispheres were qualitatively similar to those in the VII hemispheres shown in Fig. 4.

Right versus left hemisphere in the control group of animals

The general features – size, shape and location – of vibrissal representation in the control hemispheres conform to previous descriptions of the rat M1 (Fig. 3A and B) (Donoghue & Wise, 1982). In general, the vibrissa representation is an anteroposteriorly elongated strip extending from the bregma 4 mm anteriorly and 1–2.5 or 1–3 mm laterally. In the hemispheres of the control group of animals, the electrical stimulation of vibrissa representation at the threshold current evoked contralateral vibrissa movement in the vast majority of sites; ipsilateral vibrissae movement were only occasionally observed at the threshold current (Fig. 7; 1.59% of total sites in the histograms). The forelimb representation is situated laterally to the vibrissa region at the same anteroposterior coordinates. Hindlimb representation delimited the posterior boundary of the vibrissa and forelimb representation. In the frontal cortex strip situated medially to the vibrissa representation, miosis or, less commonly, eye movement was induced under the chosen stimulation conditions (Hall & Lindholm, 1974; Donoghue & Wise, 1982; Gioanni & Lamarche, 1985; Guandalini, 2001, 2003). Ineffective sites formed the basis for delineating the rostral MI border.

Statistical comparison between the right and left hemispheres of the control group of animals showed no significant difference in the mean size of the vibrissa movement representation (right hemisphere: mean size 4.35 ± 0.52 mm, range 3.5–5.5 mm; left hemisphere: mean size 3.9 ± 0.33 mm, range 3.25–4.5 mm; P = 0.3, paired t test). Statistical comparison also showed no significant difference in the percentage of movement sites (eye, P = 0.24; vibrissae, P = 0.44; forelimb, P = 0.9; paired t test) and in the mediolateral frequency distributions of the contralateral vibrissa and forelimb sites (Fig. 3B; vibrissae, χ20.05;1 = 0.04; and forelimb, χ20.05;1 = 0.002; 2 × 2, 2.5 mm as dividing point; P > 0.05 χ2 test). Similarly, no significant differences in evoked movement thresholds were found between the right and left hemispheres of the control group of animals (eye, P = 0.96; vibrissae, P = 0.26; forelimb, P = 0.44; hindlimb, P = 0.95; paired t test). The fact that there were no statistical differences between the right and left hemisphere of the control group of animals ensured that, in absence of peripheral manipulation, sources of variability were minor and not consistent between the right and left hemispheres of a small number of animals.

Hypothesis 1: the loss of an ION signal induces motor cortex plasticity

If the ION signals have an influence on M1 neurons, then it is possible that the persistent withdrawal of an ION input to M1 neurons could induce M1 plasticity. This hypothesis predicts that ION versus control hemispheres should be significantly different. Comparison of the ION (n = 10) and control (n = 10) hemispheres showed no significant difference in percentage of movement sites evoked in the two groups of hemispheres (Fig. 7 and Table 1; P > 0.05 Scheffé test) and in the mediolateral frequency distributions of the contralateral vibrissa (χ20.05;1 = 2.1; 2 × 2, 2.5 mm as dividing point; P > 0.05 χ2 test) and the forelimb sites (Fig. 8A, ION versus control, χ20.05;1 = 0.4; 2 × 2, 2.5 mm as dividing point; P > 0.05 χ2 test). In comparison with the control hemispheres, the threshold currents required to evoke contralateral vibrissa movement in the ION hemispheres were slightly, but not significantly, higher (ION, 22.3 ± 0.6; control, 21.2 ± 1.8; Table 2, hypothesis 1; P > 0.05 Scheffé test). No significant differences in evoked movement thresholds were found in other types of movement (see Table 2; P > 0.05 Scheffé test). Thus, the present experiments showed no evidence that, after a period of more than 2 weeks, the vibrissa pad deafferentation produced significant plastic changes within the vibrissa motor representation. In sum, these data do not support the hypothesis 1.

Table 1.

Across-group comparisons of ineffective and effective sites for various movements represented in M1 (up to 2.5 mm from the midline) using the Scheffé test

| Hypothesis | IN | Vc | Vi | Nk | E | FL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 + 3 | ION vs. control | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.46 | 1.84 | 0.005 | |

| 2 | VII vs. control | 23.33§ | 15.58§ | 44.53§ | 4.91 | 15.10§ | |

| 2 + 3 | VII vs. ION + VII | 0.35 | 0.08 | 5.05 | 1.49 | 0.17 | |

| 2 + 3 | VII vs. ION + BTX | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.92 | 3.52 | 0.17 | |

| 3 | ION vs. VII | 21.69§ | 37.42§ | 1.23 | 15.64§ | ||

| 3 | ION vs. ION + VII | 28.60§ | 12.40§ | 12.40§ | 0.09 | 19.55§ | |

| 3 | ION vs. ION + BTX | 21.69§ | 11.25§ | 52.26§ | 1.12 | 19.57§ | |

| 2 | ION + VII vs. ION + BTX | 0.35 | 0.02 | 8.35§ | 0.42 | 3.8 × 10−6 | |

| * | † | ‡ | ‡ | * | * |

Comparisons are organized in accordance with the hypotheses 1, 2 and 3. Scheffé test critical value according to degrees of freedom in each comparison:

S2(0.05;4,30) = 10.76;

S2(0.05;1,18) = 4.41;

S2(0.05;2,12) = 7.78;

P < 0.05. IN, ineffective sites; Vc, contralateral vibrissa; Vi, ipsilateral vibrissa; Nk, neck; E, eye; FL, forelimb.

Table 2.

Across-group comparisons of the threshold currents that elicit movements for all groups using Scheffé test

| Hypothesis | E | Vc | Vi | Nk | FL | HL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 + 3 | ION vs. control | 0.007 | 3.28 | 0.10 | 0.59 | ||

| 2 | VII vs. control | 0.05 | 7.36 | 0.80 | |||

| 2 + 3 | VII vs. ION + VII | 0.01 | 2.00 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.43 | |

| 2 + 3 | VII vs. ION + BTX | 2.18 | 1.97 | 0.003 | 0.62 | 0.38 | |

| 3 | ION vs. VII | 0.02 | 6.01 | 0.07 | |||

| 3 | ION vs. ION + VII | 0.001 | 7.29 | 0.24 | |||

| 3 | ION vs. ION + BTX | 3.49 | 11.33§§ | 0.95 | |||

| 2 | ION + VII vs. ION + BTX | 2.50 | 0.0001 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 1.63 | |

| * | † | ‡ | ‡ | * | * |

Comparisons are organized in accordance with the hypotheses 1, 2 and 3. Scheffé test critical value according to degrees of freedom in each comparison:

S2(0.05;4,30) = 10.76;

S2(0.05;1,18) = 4.41;

S2(0.05;2,12) = 7.78;

P < 0.05. IN, ineffective sites; Vc, contralateral vibrissa; Vi, ipsilateral vibrissa; Nk, neck; E, eye; FL, forelimb.

Hypothesis 2: the ION carries a signal that induces motor cortex plasticity

If the persistent withdrawal of an ION input to M1 neurons not produced significant plastic changes within the vibrissa motor representation, it is possible that the abnormal ION signal to M1 neurons after vibrissa muscle paralysis could trigger M1 reorganization. This hypothesis predicts that VII versus ION + VII and ION + BTX hemispheres should be significantly different.

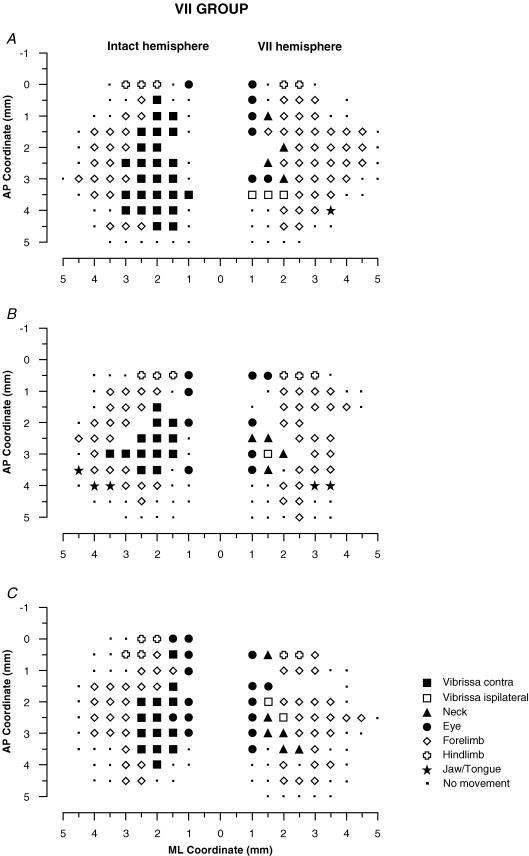

Examination of the motor maps in Figs 4–6 revealed that the reorganization of vibrissae movement representation clearly emerges only in hemispheres where the contralateral vibrissae pad underwent motor-output disconnection. As shown in the plots in Figs 7–10, the reorganization of vibrissae motor representation 48 h after facial nerve transection is characterized by the following. (1) An increase in the percentage of ineffective sites inside the former vibrissa representation (Fig. 7 and Table 1, VII versus control hemispheres; P < 0.05 Scheffé test). (2) An increase in the percentage of ipsilateral vibrissa and neck sites (Fig 7C and D, and Table 1, VII versus control hemispheres; P < 0.05 Scheffé test). Ipsilateral vibrissa and neck sites consisted of contiguous or separated foci. In these sites, higher-than-threshold electrical stimulation often elicited both ipsilateral and neck movements. Thresholds for ipsilateral vibrissa and neck movements were higher than thresholds required to evoke contralateral vibrissa movement in the corresponding area in the control hemispheres. (3) An increase in the percentage of forelimb sites (Fig. 7E and Table 1, VII versus control hemispheres; P < 0.05 Scheffé test). In the VII hemispheres, forelimb sites distribution shifted medially when compared with the distribution in the control hemispheres (Fig. 8B, VII versus control hemispheres: χ20.05;1 = 4.5; 2 × 2, 2.5 mm as dividing point; P < 0.05, χ2 test). This means that the forelimb sites expand in the cortical region nearly corresponding to the lateral part of the normal vibrissa motor representation. Thresholds for forelimb movement in the VII hemispheres were slightly, but not significantly, higher than thresholds for forelimb movement in the control hemispheres (VII versus control hemispheres, 23.6 ± 2.9 versus 19.1 ± 3.4; Table 2; P > 0.05 Scheffé test). Figure 9 shows that the increase in the forelimb thresholds in the VII hemispheres involves selectively the forelimb sites localized up to 3 mm lateral to the midline (left bar, S20.05;5,24 = 22.8, P < 0.05; right bar, S20.05;5,24 = 0.006, P > 0.05, Scheffé test). That is, 48 h after severing facial nerve, the forelimb sites emerging in the cortical region that nearly corresponds to the lateral part of the normal vibrissa motor representation showed thresholds significantly higher than those found in sites normally devoted to forelimb movement.

Figure 4. Surface view maps in a VII group.

Examples of bilateral vibrissa maps from three rats (A, B and C) showing one hemisphere with the contralateral vibrissa pad with intact input–output condition (intact hemisphere) and the other with the contralateral vibrissa pad with facial-nerve-cut-induced motor paralysis (VII hemisphere). Intact hemispheres showed a large contralateral vibrissa movement representation. In the VII hemisphere there was evidence of persistent ipsilateral vibrissae and neck movements in the medial part of the former vibrissa representation. Moreover, it is worth noting that the forelimb expanded medially inside the former vibrissa representation.

To examine whether the persistent loss of vibrissae receptor input actually changes the pattern of M1 reorganization during the first 48 h after motor disconnection, comparison was made between VII versus ION + VII and ION + BTX hemispheres. In spite of interindividual variability, qualitative comparison between VII versus ION + VII and ION + BTX hemispheres showed similar reorganization patterns in all maps (Figs 4–6). Quantitative comparison showed the following. (1) There was no difference in the types of movement evoked within the disconnected vibrissa motor representation, and no significant difference in the increase in percentage of movement sites localized from 1 to 2.5 mm lateral to the midline (Fig. 7 and Table 1, VII versus ION + VII hemispheres, and VII versus ION + BTX hemispheres; P > 0.05 Scheffé test). (2) There was no significant difference in the mediolateral frequency distributions of the forelimb sites (Fig. 8B, VII/ION + VII/ION + BTX hemispheres: χ20.05;2 = 0.3; 3 × 2, 2.5 mm as dividing point; P > 0.05 χ2 test). (3) There was no significant differences in evoked movement thresholds (Table 2, P > 0.05 Scheffé test) and in the mediolateral distribution of forelimb thresholds were found between VII and ION + VII and ION + BTX hemispheres (Fig 10B; P > 0.05 ANOVA). All these data show that the vibrissae receptor input does not affect the type and threshold of movements emerging within the disconnected vibrissa motor region over time.

Quantitative comparisons between ION + VII and ION + BTX hemispheres showed no significant differences in the percentage of movement sites (Fig. 7 and Table 1; P > 0.05 Scheffé test) and in the mediolateral frequency distribution of the forelimb sites (Fig. 8B, ION + VII versus ION + BTX: χ20.05;1 = 0.31; 2 × 2, 2.5 mm as dividing point; P > 0.05 χ2 test). Similarly, no significant differences in evoked movement thresholds were found (Table 2; P > 0.05 Scheffé test). This comparison showed that different types of motor disconnection in deafferented animals do not induce differences in the time course for the reorganization of vibrissae motor representation.

Thus, there was no evidence that persistent vibrissae pad deafferentation actually changes the short-term pattern of reorganization of the vibrissae motor representation after vibrissae pad motor-output disconnection. In the light of this, these data not support hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 3: ION signal is irrelevant for motor cortex reorganization following vibrissa muscle paralysis

If the persistent withdrawal of the ION signal does not induce M1 plasticity, and the presence of an abnormal ION signal to M1 neurons does not trigger M1 plasticity, it is possible that the ION signal does not influence the large M1 reorganization following the vibrissae muscle paralysis. This hypothesis predicts that (1) ION and control hemispheres should be the same; (2) ION and VII hemispheres should be different; (3) beyond the predictions of hypothesis 2, hypothesis 3 predicts that ION, ION + VII and ION + BTX hemispheres should be different; (4) VII, ION + VII and ION + BTX hemispheres should be the same. All of these comparisons are clearly supported by the present results (see Figs 6–10, and Tables 1 and 2), which clearly support hypothesis 3. Thus, we can conclude that the reorganization of vibrissae movement representation clearly emerges only in hemispheres where the contralateral vibrissae pad underwent motor-output disconnection, and that the infraorbital signal is irrelevant for this form of motor plasticity.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that the precondition for a loss of vibrissae receptor input does not cause reorganization of the M1 topographic map, nor does it alter the pattern of M1 reorganization 48 h after vibrissae motor disconnection. Because it has previously been demonstrated that large reorganization of vibrissae motor representation takes place during the first 48 h after vibrissae motor-output disconnection (Sanes et al. 1988; Donoghue et al. 1990; Toldi et al. 1996; Huntley, 1997a; Franchi, 2002), we now conclude that the vibrissae input does not provide a gating signal to trigger this form of M1 reorganization. The main reason may be the nature of whisking movements, e.g. a relatively simple form of movement, restricted to only a single dimension and where load plays a minor role. Moreover, behavioural and deafferentation data suggest that the rhythmic sweeps of the mystacial vibrissae are, for the most part, centrally preprogrammed feedback-independent movements (Welker, 1964; Gao et al. 2001; Hattox et al. 2002; Berg & Kleinfeld, 2003; Ahrens & Kleinfeld, 2004). However, human experiments have shown that other forms of motor cortex plasticity require sensory feedback for them to occur (Ziemann et al. 1998; Hamdy et al. 1998; Ridding et al. 2000; Stefan et al. 2000).

Peripheral signals and M1 reorganization

We do not know what type of signal induces M1 reorganization minutes and hours after peripheral motor disconnection (Sanes et al. 1990; Toldi et al. 1996; Huntley, 1997a). However, the present results might be helpful in identifying such signals. The hypothesis that, in the adult rat, continuous vibrissae sensory feedback is not necessary to maintain M1 vibrissae representation has long been supported by data demonstrating normal shape and size of vibrissae motor representation after vibrissae trimming (Huntley, 1997b) or persistent ION injury (Franchi, 2001). The present study adds additional support for this conclusion, and shows that abnormal ION-mediated sensory feedback to M1 is not a cue for M1 reorganization after vibrissae motor-output disconnection.

Signals induced by nociceptors and conveyed through non-ION branches by C-fibres could trigger M1 reorganization in all VII-operated rats. The finding that, in ION-deafferented rats, the injection of BTX into pad muscles leads to a reorganization similar to that seen following severing of the facial nerve does not support this hypothesis.

The present experiment does not rule out the possibility that some other set of nondominant inputs from the face, neck and forelimb may be relayed to the vibrissa motor region (Schroeder et al. 1995; Moore & Nelson, 1998). Thus, abnormal nondominant input from face, neck and forelimb to the vibrissae motor region could trigger and drive the M1 reorganization after vibrissae motor output disconnection. According to this hypothesis, the nondominant forelimb input to the vibrissa motor region could drive the emergence (within hours, Sanes et al. 1988; Donoghue et al. 1990; Huntley, 1997a; present data) and the subsequent consolidation (after days, Sanes et al. 1990; Franchi, 2000b, 2002) of the forelimb movement inside the lateral part of the former vibrissa representation. However, this hypothesis does not explain the initial reaction that takes place within a few minutes and which disinhibits transcallosal connections between homotopic vibrissa regions in both hemispheres (Toldi et al. 1996, 1999; Farkas et al. 2000; Horvath et al. 2005). Hours later, when this initial reaction disappears, the subthreshold input might play a role in facilitation of the intra-areal connections between the vibrissa region and neighbouring representations.

The finding that M1 reorganization clearly emerges only when the motor nerve is severed or neuromuscular transmission is blocked, with or without ION signals, also suggests that the cortical reorganization may be triggered by signals starting from peripheral motor structures. Peripheral axotomy induces changes in the discharge properties of both motor and internuclear neurons in the central nervous system (De la Cruz et al. 2000). The early phase of the ‘axotomy reaction’ could be initiated by electrical disturbances that antidromically convey information regarding motor axon damage from the periphery to the motor neuron body (Mader et al. 2004), and this might have adverse effects on the firing of facial motor neurons. Moreover, the initial response of BTX-treated motor neurons resembles some of the functional changes found in these neurons following an axotomy (Delgado-Garcia et al. 1988; Pastor et al. 1997). Thus, the present results suggest that cortical reorganization could be secondary to changes in the firing of facial nucleus motor neurons and interneurons (Li et al. 2004; Ikeda & Kato, 2005; Vassias et al. 2005) triggered by both axotomy and inactivation of neuromuscular synapsis (see the scheme in the Fig. 11).

Sub-cortical and cortical mechanisms of M1 reorganization

There is experimental evidence that, in the rat, rhythmic whisking is maintained by the whisking central pattern generator (CPG) at the level of medulla (Gao et al. 2001, 2003; Hattox et al. 2003), whereas voluntary initiation and modulation of the whisking pattern are mediated by cortical mechanisms (Carvel et al. 1996; Friedman et al. 2006). There is also evidence to support the hypothesis that the source of rhythmic activity in the vibrissa cortex, phase-locked with exploratory rhythmic whisking, can be the efference copy originating in the brainstem CPG and ascending to the M1 cortex (Ahrens & Kleinfeld, 2004; Friedman et al. 2006). However, there is as yet no direct evidence that such ascending pathway(s) exist.

The finding that M1 reorganization clearly emerges only when the motor nerve is severed or neuromuscular transmission is blocked, with or without ION signals, supports the suggestion that an altered efference copy could trigger and preserve vibrissa motor cortex reorganization. If the shaping and size of the vibrissa motor representation is based on efference copy, then it is possible to understand the lack of effect of ION nerve transection. When the motor output is blocked, the nature of the efference copy ascending to the motor cortex could change; in this way, an abnormal efference copy could trigger M1 reorganization and could explain how, in the absence of ION feedback, the motor cortex knows that its link to the vibrissae muscles is not normal. These explanations assume that the changes also occur in subcortical circuits closer to the periphery involving facial motor neurons and circuits that receive efference copy of motor commands which could act as a conduit for signals from the brainstem to thalamus and finally to the M1 cortex. Possible candidate pathways that could trigger M1 output reorganization might include all thalamic inputs to M1. Thus, after vibrissae output disconnection, the restriction of the vibrissae movement could first induce changes in motor-related structures outside the primary motor cortex. The observed changes in the M1 motor map might be triggered by input from either the basal ganglia (Sharp & Evans, 1982; Hauber et al. 1998), or the cerebellum (Kotchabhakdi & Walberg, 1977; Angaut & Cicirata, 1994), or both, and enabled by cholinergic inputs from the basal forebrain (Juliano et al. 1991; Höhmann et al. 1991; Webster et al. 1991). The scheme in the Fig. 11 shows the proposed mechanisms for short-term reorganization of input-deprived motor vibrissae representation following motor disconnection.

Animal work has demonstrated the role of the horizontal connections within M1 as a neural substrate for cortical plasticity (Donoghue, 1995; Hess et al. 1996; Hess & Donoghue, 1996; Huntley, 1997a; Sanes & Donoghue, 2000). It has been suggested that these horizontal corticocortical connections are long-range collaterals of pyramidal neurons normally suppressed by local inhibitory interneurons (Jones, 1993; Kew et al. 1997). In models of cortical map plasticity, the first step in cortical map reorganization is the loss of local interneuron inhibition (Calford & Tweedale, 1991; Jones, 1993; Donoghue, 1995; D'Amelio et al. 1996; Toldi et al. 1996; Calford, 2002). Motor cortex map plasticity in the adult rat can be evoked by intracortical injection of the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline. Bicuculline injection in M1 induces a blockade of local inhibitory interneurons and permits functional linking of separate motor cortical points, unmasking pre-existing horizontal connections within M1 (Jacobs & Donoghue, 1991; Schneider et al. 2002). The present results indicate that persistent vibrissae sensory deprivation does not mimic the effects of the intracortical injection of bicuculline in M1. In contrast, effects comparable to the intracortical injection of bicuculline (i.e. switching normal cortical output) are strictly triggered by the restriction of vibrissae movement in animals with or without vibrissae sensory input. Thus we conclude that persistent ION-deafferentation does not drive the persistent downregulation of local inhibitory interneurons in M1. The possibility of rapid deefferentation-induced changes in cortical inhibition has been evidenced in rat M1 (Farkas et al. 2000). Indeed, facial nerve injury resulted in rapid disinhibition of the disconnected cortex when the animals were tested by paired intracortical microstimulation. This observation and the present results lead to the hypothesis that the persistent downregulation of local inhibitory interneurons – with the unmasking of pre-existing horizontal connections between the vibrissa and forelimb representation – is triggered by the persistent abnormal motor output following the vibrissae output disconnection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr C. Lucchetti for manuscript revision, and Ing. E. Lodi who wrote the software for the on-line mapping procedures. We thank Dott. V. Muzzioli for his assistance with preparation of the figures. We are also grateful to S. Zanellati for her assistance during histological procedures.

References

- Ahrens KF, Kleinfeld D. Current flow in vibrissa motor cortex can phase-lock with exploratory rhythmic whisking in rat. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:1700–1707. doi: 10.1152/jn.00020.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angaut P, Cicirata F. Anatomo-functional organization of the neocerebellar control pathways on the cerebral motor cortex. Rev Neurol. 1994;150:39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong-James M, George MJ. Bilateral receptive fields of cells in rat Sm1 cortex. Exp Brain Res. 1988;70:155–165. doi: 10.1007/BF00271857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asanuma H, Stoney SJ, Abzung C. Relationship between afferent input and motor outflow in cat motorsensory cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1968;31:670–681. doi: 10.1152/jn.1968.31.5.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg WR, Kleinfeld D. Vibrissae movement elicited by rhythmic electrical microstimulation to motor cortex in the aroused rat mimics exploratory whisking. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:2950–2963. doi: 10.1152/jn.00511.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasil-Neto JP, Valls-Sole J, Pascual-Leone A, Cammarota A, Amassian VE, Cracco R, Maccabee P, Cracco J, Hallett M, Cohen LG. Rapid modulation of human cortical motor outputs following ischaemic nerve block. Brain. 1993;116:511–525. doi: 10.1093/brain/116.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calford MB. Mechanisms for acute changes in sensory maps. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;508:451–460. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0713-0_51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calford MB, Tweedale R. Acute changes in cutaneous receptive fields in primary somatosensory cortex after digit denervation in adult flying fox. J Neurophysiol. 1991;65:178–187. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.65.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvel GE, Miller SA, Simonds DJ. The relationship of vibrissal motor cortex unit activity to whisking in the awake rat. Somatosens Motor Res. 1996;13:115–127. doi: 10.3109/08990229609051399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LG, Brasil-Neto JP, Pascual-Leone A, Hallet M. Plasticity of cortical motor output organization following deafferentation, cerebral lesions and skill acquisition. Adv Neurol. 1993;63:187–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amelio F, Fox RA, Wu LC, Daunton NG. Quantitative changes of GABA-immunoreactive cells in the hindlimb representation of the rat somatosensory cortex after 14-day hindlimb unloading by tail suspension. J Neurosi Res. 1996;44:532–539. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19960615)44:6<532::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Cruz RR, Delgado-Garcia JM, Pastor AM. Discharge characteristics of axotomized abducens internuclear neurons in the adult cat. J Comp Neurol. 2000;427:391–404. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001120)427:3<391::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Garcia JM, del Pozzo F, Spencer RF, Baker R. Behavior of neurons in the abducens nucleus of the alert cat-III. Axotomized motoneurons. Neuroscience. 1988;24:143–160. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90319-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue JP. Plasticity of adult sensorimotor representation. Current Opin Neurobiol. 1995;5:749–754. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(95)80102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue JP, Suner S, Sanes JN. Dynamic organization of primary motor cortex output to target muscles in adult rats. II. Rapid reorganization following motor nerve lesion. Exp Brain Res. 1990;79:492–503. doi: 10.1007/BF00229319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue JP, Wise SP. The motor cortex of the rat: cytoarchitecture and microstimulation mapping. J Comp Neurol. 1982;212:76–88. doi: 10.1002/cne.902120106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas T, Kis Z, Toldi J, Wolff JR. Activation of the primary motor cortex by somatosensory stimulation in adult rats is mediated mainly by associational connections from the somatosensory cortex. Neuroscience. 1999;90:353–361. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00451-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas T, Perge J, Kis Z, Wolff JR, Toldi J. Facial nerve injury-induced disinhibition in the primary motor cortices of both hemispheres. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:2190–2194. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchi G. Reorganization of vibrissal motor representation following severing and repair of the facial nerve in adult rats. Exp Brain Res. 2000a;131:33–43. doi: 10.1007/s002219900297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchi G. Changes in motor representation related to facial nerve damage and regeneration in adult rats. Exp Brain Res. 2000b;135:53–65. doi: 10.1007/s002210000503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchi G. Persistence of vibrissal motor representation following vibrissal pad deafferentation in adult rats. Exp Brain Res. 2001;137:180–189. doi: 10.1007/s002210000652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchi G. Time course of motor cortex reorganization following botulinum toxin injection into the vibrissal pad of the adult rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:1333–1348. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman WA, Jones LM, Cramer NP, Kwegyir EE, Zeigler HP. Anticipatory activity of motor cortex in relation to rhythmic whisking. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:1274–1277. doi: 10.1152/jn.00945.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao P, Bermejo R, Zeigler HP. Vibrissa deafferentation and rodent whisking patterns: Behavioural evidence for a central pattern generator. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5374–5380. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-05374.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao P, Hattox AM, Jones LM, Keller A, Zeigler HP. Whisker motor cortex ablation and whisker movement patterns. Somatosens Motor Res. 2003;20:191–198. doi: 10.1080/08990220310001622924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gioanni Y, Lamarche M. A reappraisal of rat motor cortex organization by intracortical microstimulation. Brain Res. 1985;344:49–61. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91188-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guandalini P. The corticocortical projections of the physiologically defined eye field in the rat medial frontal cortex. Brain Res Bull. 1998;47:377–385. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(98)00122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guandalini P. The efferent connections to the thalamus and brainstem of the physiologically defined eye field in the rat medial frontal cortex. Brain Res Bull. 2001;54:175–186. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(00)00444-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guandalini P. The efferent connections of the papillary constriction area in the rat medial cortex. Brain Res. 2003;962:27–40. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03931-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall DH, Lindholm E. Organization of motor and somatosensory neocortex in the albino rat. Brain Res. 1974;66:23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hamdy S, Rotwell JC, Aziz Q, Singh KD, Thompson DC. Long-term reorganization of human motor cortex driven by short-term sensory stimulation. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:64–68. doi: 10.1038/264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattox AM, Li Y, Keller A. Serotonin regulates rhytmic whisking. Neuron. 2003;39:343–352. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00391-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattox AM, Priest CA, Keller A. Functional circuitry involved in the regulation of whisker movements. J Comp Neurol. 2002;442:266–276. doi: 10.1002/cne.10089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauber W, Lutz S, Munkle M. The effects of globus pallidus lesions on dopamine-dependent motor behavior in rats. Neuroscience. 1998;86:147–157. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess G, Aizenman CD, Donoghue JP. Conditions for the induction of long-term potentiation in layer II/III horizontal connections of the rat motor cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1996;75:1765–1778. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.5.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess G, Donoghue JP. Long-term depression of horizontal connections in rat motor cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 1996;8:658–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höhmann CF, Wilson L, Coyle JT. Efferent and afferent connections of mouse sensory-motor cortex following cholinergic deafferentation at birth. Cereb Cortex. 1991;1:158–172. doi: 10.1093/cercor/1.2.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath S, Prandovszky E, Pankotai E, Kis Z, Farkas T, Boldogkoi Z, Boda K, Janka Z, Toldi J. Use of a recombinant pseudorabies virus to analyze motor cortical reorganization after unilateral facial denervation. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15:378–384. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntley GW. Correlation between pattern of horizontal connectivity and the extent of short-term representational plasticity in rat motor cortex. Cereb Cortex. 1997a;7:143–156. doi: 10.1093/cercor/7.2.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntley GW. Differential effect of abnormal tactile experience on shaping representation patterns in developing and adult motor cortex. J Neurosci. 1997b;17:9220–9232. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-23-09220.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda R, Kato F. Early and transient increase in spontaneous synaptic inputs to the rat facial motoneurons after axotomy in isolated brainstem slices of rats. Neuroscience. 2005;134:889–899. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs KM, Donoghue JP. Reshaping the cortical motor map by unmasking latent intracortical connections. Science. 1991;251:944–945. doi: 10.1126/science.2000496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EG. GABAergic neurons and their role in cortical plasticity in primates. Cereb Cortex. 1993;3:361–372. doi: 10.1093/cercor/3.5.361-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juliano SL, Ma W, Eslin D. Cholinergic depletion prevents expansion of topographic maps in somatosensory cortex. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:780–784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.3.780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH. The reorganization of somatosensory and motor cortex after peripheral nerve or spinal cord injury in primates. Prog Brain Res. 2000;128:173–179. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(00)28015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kew JJ, Halligan PW, Marshall JC, Passingham RE, Rothwell JC, Ridding MC, Marsden CD, Brooks J. Abnormal access of axial vibrotactile input to deafferented somatosensory cortex in human upper limb amputees. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:2753–2764. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.5.2753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotchabhakdi N, Walberg F. Cerebellar afferents from neurons in motor nuclei of cranial nerve demonstrated by retrograde axonal transport of horseradish peroxidase. Brain Res. 1977;137:158–163. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)91020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakauer J, Ghez C. Voluntary movement. In: Kandel ER, Schwartz JH, Jessel TM, editors. Principles of Neural Science. 4. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Guan Z, Chan Y, Zheng Y. Projections from facial nucleus interneurons to the respiratory groups of brainstem in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 2004;368:25–28. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.06.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mader K, Andermahr J, Angelov DN, Neiss WF. Dual mode of signaling of the axotomy reaction: retrograde electric stimulation or block of retrograde transport differently mimic the reaction of motoneurons to nerve transection in the rat brainstem. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:956–968. doi: 10.1089/0897715041526113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore CI, Nelson SB. Spatio-temporal subtreshold receptive fields in the vibrissa representation of the rat primary somatosensory cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:2882–2892. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.6.2882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor AM, Moreno-Lopez B, De La Cruz RR, Delgado-Garcia JM. Effects of Botulinum neurotoxin type A on abducens motoneurons in the cat: ultrastructural and synaptic alterations. Neuroscience. 1997;81:457–478. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00200-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penfield W, Rasmussen T. The Cerebral Cortex of Man. New York: MacMillan; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Qi HX, Stepniewska I, Kaas JH. Reorganization of primary motor cortex in adult macaque monkeys with long-standing amputations. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:2133–2147. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.4.2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridding MC, Brouwer B, Miles TS, Pitcher JB, Thompson PD. Changes in muscle responses to stimulation of the motor cortex induced by peripheral nerve stimulation in human subjects. Exp Brain Res. 2000;131:135–143. doi: 10.1007/s002219900269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosèn I, Asanuma H. Peripheral afferent input to the forelimb area of the monkey motor cortex: input–output relations. Exp Brain Res. 1972;14:257–273. doi: 10.1007/BF00816162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanes JN, Donoghue JP. Plasticity and primary motor cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:393–415. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanes JN, Suner S, Donoghue JP. Dynamic organization of primary motor cortex output to target muscles in adult rats. I. Long-term pattern of reorganization following motor or mixed peripheral nerve lesion. Exp Brain Res. 1990;79:479–491. doi: 10.1007/BF00229318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanes JN, Suner S, Lando JF, Donoghue JP. Rapid reorganization of adult rat motor cortex somatic representation patterned after motor nerve injury. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:2003–2007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.6.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanes JN, Wang J, Donoghue JP. Immediate and delayed changes of rat motor cortical output representation with new forelimb configurations. Cereb Cortex. 1992;2:141–152. doi: 10.1093/cercor/2.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieber MH, Deuel RK. Primary motor cortex reorganization in a long-term monkey amputee. Somatos Mot Res. 1997;14:157–167. doi: 10.1080/08990229771024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C, Devanne H, Brigitte A, Lavoie A, Capady C. Neural mechanisms involved in the functional linking of motor cortical points. Exp Brain Res. 2002;146:86–89. doi: 10.1007/s00221-002-1137-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder CE, Seto S, Arezzo JC, Garraghty PE. Electrophysiological evidence for overlapping dominant and latent inputs to somatosensory cortex in squirrel monkeys. J Neurophysiol. 1995;74:722–732. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.2.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp FR, Evans K. Regional [14C]2-deoxyglucose uptake during vibrissae movements evoked by rat motor cortex stimulation. J Comp Neurol. 1982;208:255–287. doi: 10.1002/cne.902080305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievert CF, Neafsey EJ. A chronic unit study of the sensory properties of neurons in the forelimb areas of the rat sensorimotor cortex. Brain Res. 1986;381:15–23. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90684-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefan K, Kunesch E, Choen LG, Benecke R, Classen J. Induction of plasticity in the human motor cortex by paired associative stimulation. Brain. 2000;123:572–584. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.3.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toldi J, Farkas T, Perge J, Wolff JR. Facial nerve injury produces a latent somatosensory input through recruitment of the motor cortex in the rat. Neuroreport. 1999;10:2143–2147. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199907130-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toldi J, Laskawi R, Landgrebe M, Wolff JR. Biphasic reorganization of somatotopy in the primary motor cortex follows facial nerve lesion in adult rats. Neurosci Lett. 1996;203:179–182. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)12295-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassias I, Lecolle S, Vidal PP, de Waele C. Modulation of GABA receptor subunits in rat facial motoneurons after axotomy. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;135:260–275. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster HH, Hanisch UK, Dykes RW, Biesold D. Basal forebrain lesions with or without reserpine injection inhibit cortical reorganization in rat hindpaw primary somatosensory cortex following sciatic nerve section. Somatosens Mot Res. 1991;8:327–346. doi: 10.3109/08990229109144756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welker WI. Analysis of sniffing of the albino rat. Behaviour. 1964;12:223–244. [Google Scholar]

- Wong YC, Kwan HC, Mac Ka, WA, Murphy JT. Spatial organization of precentral cortex in awake primates. I. Somatosensory inputs. J Neurophysiol. 1978;41:1107–1119. doi: 10.1152/jn.1978.41.5.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolsey CN, Settlage PH, Meyer DR, Sencer W, Hamuy TP, Travis AM. patterns of localization in precentral and ‘supplementary’ motor areas and their relation to the concept of a premotor area. Res Publ Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis. 1952;30:238–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CW, Kaas JH. Reorganization in primary motor cortex of primates with long-standing therapeutic amputations. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7679–7697. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07679.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziemann U, Corwell B, Cohen LG. Modulation of plasticity in human motor cortex after forearm ischemic nerve block. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1115–1123. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-03-01115.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]