Abstract

Results from phylogenetic analysis of nuclear rDNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences from a worldwide sample of Sanicula indicate that Hawaiian sanicles (Sanicula sect. Sandwicenses) constitute a monophyletic group that descended from a western North American ancestor in Sanicula sect. Sanicoria, a paraphyletic assemblage of mostly Californian species. A monophyletic group comprising representatives of all 15 species of S. sect. Sanicoria and the three sampled species of S. sect. Sandwicenses was resolved in all maximally parsimonious trees, rooted with sequences from species of Astrantia and Eryngium. All sequences sampled from eastern North American, European, and Asian species of Sanicula fell outside the ITS clade comprising S. sect. Sanicoria and S. sect. Sandwicenses. A lineage comprising the Hawaiian taxa and three species endemic to coastal or near-coastal habitats in western North America (Sanicula arctopoides, Sanicula arguta, and Sanicula laciniata) is diagnosed by nucleotide substitutions and a 24-bp deletion in ITS2. The hooked fruits in Sanicula lead us to conclude that the ancestor of Hawaiian sanicles arrived from North America by external bird dispersal; similar transport has been hypothesized for the North American tarweed ancestor of the Hawaiian silversword alliance (Asteraceae). Two additional long-distance dispersal events involving members of S. sect. Sanicoria can be concluded from the ITS phylogeny: dispersal of Sanicula crassicaulis and Sanicula graveolens from western North America to southern South America.

The volcanic history, extreme geographic isolation, and disharmonic biota of the Hawaiian archipelago demonstrate that terrestrial life in the islands must have arrived by long-distance dispersal (1). Among plants, the approximately 966 species of indigenous Hawaiian angiosperms (89% endemic) have been estimated to stem from 272 to 282 natural introductions to the islands (2). On the basis of comparative floristics, Fosberg (3) hypothesized that most natural introductions of Hawaiian flowering plants were from southeast Asian source areas. Directionality of prevailing air currents, occurrence of intermediary “stepping-stone” islands, and climatic similarities between the Hawaiian archipelago and tropical areas to the west and southwest of the islands accord with Fosberg’s estimate.

A minority (about 18%) of ancestral Hawaiian plant colonists are thought to have dispersed from the Americas (3), despite unfavorable prevailing winds and water currents. Plant dispersal across the unbroken 3,900-km oceanic barrier between temperate western North America and the Hawaiian Islands appears to have been exceedingly rare. Molecular phylogenetic evidence of a California tarweed (Madia/Raillardiopsis) ancestry of the Hawaiian silversword alliance (Argyroxiphium, Dubautia, Wilkesia) provides one unequivocal example of such dispersal in the sunflower family (4–6). In this paper, we provide phylogenetic evidence from nuclear ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences for another example of angiosperm dispersal from the Pacific coast of temperate western North America to the Hawaiian Islands involving Sanicula (Apiaceae). In addition, we show evidence for two amphitropical dispersals of sanicles from temperate western North America to southern South America.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We examined DNAs from one to six populations of 23 species representing all 15 taxa in the western American Sanicula sect. Sanicoria, three of four species in the Hawaiian Sanicula sect. Sandwicenses (Sanicula kauaiensis may be extinct), two of six species from the Asian Sanicula sect. Pseudopetagnia, and three of 13 species from the cosmopolitan Sanicula sect. Sanicla (for taxonomy of Sanicula see refs. 7–10). The only section not examined was the Asian Sanicula sect. Tuberculatae, comprising three species (unavailable to us) regarded by Shan and Constance (7) as having “diverged least from the assumed progenitors . . . of the genus.” Sampling encompassed the main continental distribution of the genus (Asia, Europe, North America, and South America) and included a Malaysian sample of the only species known from Africa. Populations were sampled widely across the distribution of species represented by multiple DNAs (Table 1). Three species outside Sanicula in subfamily Saniculoideae (Astrantia major, Eryngium cervantesii, and Eryngium mexicanum) were chosen as outgroups based on morphological and molecular evidence of close relationship to the ingroup (see ref. 11).

Table 1.

Matrix of informative nucleotide sites and insertions/deletions (indels) from the nuclear rDNA ITS region in Sanicula and outgroups

| 1111111111111111111111111111 | |

| 1123344555555566666777788899990011122222233333456667778888 | |

| 57824727123578912579567804734893726901235901459353464781346 | |

| 1 | TAGGCCCCCGACATCGGGCCCCACACGGCTCGGACTCAACGGACCTCGCATGCAATCTG |

| 2 | TAGGCCACCGACGTCGGGCCCCACCTGGCTCGGCCTCAACGGCACTCGCATGCAATTTG |

| 3 | TTAGCCACGGACATTGGTCCCCCAGAGGCGCGGCTTCRATTACCACCGCATGTCACTGC |

| 4 | TTAGACACCGACGTCGGGCCCCGTTTGATCGGGCTCCGCTACAATTTATATGCCATCCT |

| 5 | TTAGACACCGACGTCGGGCTCCGTT-GACCGGGTTCCGCTACAATTTGTATGCTATCCT |

| 6 | TTAGACACCGACGTCGGGCCCTGTTCGACCGGGCTCCGCTACAACTTGTATGCCATCCT |

| 7 | TTAGATACCGACGTCGGGCCCCATTCGATCAGGCTCCGCTACAATTTGTATGCCATCCT |

| 8 | TTAGACACCGATGTCGTGCCCCGTTCGACCGGGCTCCGCTACAATTTGTATGCTATCCT |

| 9 | ATAGAAATCGACGTCGGGTTCCGTGCGATCGGGATCCGCTACAATTTATATGCCATCCT |

| 10 | ATAGAAATCGACGTCGGGTTCCGTGCGATCGGGATCCGCTACAATTTATATGCCATCCT |

| 11 | ATAGAAATCGACGTCGGGTTCCGTGCAATCGGGATCCGCTACAATTTATATGCCATCCT |

| 12 | TTAGAAATCAACGTCTGGTCCTGTTCAACCGGGCTCCGCTACAATTTATATGCCATCCT |

| 13 | TTAGAGGCCGACGTCGGGTCCCGTTCAACCGGA--CCGCTACAATTTATATGCCATCCT |

| 14 | TAAGAA-CCGACGCAGTGTCTCGTTCGACCGGGCTCTTCTACAATTTGTTTTCCATTCT |

| 15 | TTAGAAATCGACGTCGGGTCCCGTTCGACCGGGCTCCGCTACAATTTATATGCCATCCT |

| 16 | TTAAAATCCGACGTCGGGTCCTGTTCGACCGGCCTCCGCTACAATTTATACGCCACCCT |

| 17 | TTAAAATCCGACGTCGGGTCCTGTTCGACCGGCCTCCGCTACAATTTATACGCCACCCT |

| 18 | TTAAAATCCGACGTCGGGTCCTGTTCGACCGGCCTCCGCTACAATTTATACGCCACCCT |

| 19 | TTAAAATCCGACGTCGGGTCCTGTTCGACCGGCCTCCGCTACAATTTATACGCCACCCT |

| 20 | TAAGAGATCGACGTAGTGTCCCGTTCGACCGAGCTCTGCTACAATTCGTTTTTCATT-T |

| 21 | TTAGAGACGCCCGTCGTGTCCTGTTCGATCGGTTTCCGCTACAACATGTTTGCTGTACT |

| 22 | TTAGAGACGCCCGTCGTGTCCTGTTCGACCGGTTTCCGCTACAACATGTTTGCTGTACT |

| 23 | TTAGAGACGCCCGTCATGTCCTGTTTGATCGGTCTCCGCTACAACATGTTTGCTGTACT |

| 24 | TAAGAAACCAACGTAGTTTCCCGTTCGACCGGGCTCTGCTACCATTTGTTTTCCATTCT |

| 25 | TTAGAGGCCGACGTCGGGTCCYGTACGACCGGGCTCCGCTACAATTTATATGCCATCCT |

| 26 | TAAGAA-CCGACGCAGTGTCTCGTTCGACCGGGCTCTTCTACAATTTGTTTTCCATTCT |

| 27 | TTAGAGACGCCTGTCATGTCCTGTTCGACCGGTCTCCGCTACAACATGTTTGCTGTACT |

| 28 | TTAGAGACGCCCGTCATGTCCTGTTCGACCGGTCTCCGCTACAACATGTTTGTTGTACT |

| 29 | TTAGAGACGCCCGTCATGTCCTGTTTGACCGGTCTCCGCT-CAACATGTTTGCTGTACT |

| 30 | TAAGAAACCGACATAGTGTCCCGTTCGACCGAACTCTGCTACAATTCGTTTTTCATTCT |

| 31 | TAAGAAACCGAMGTAGTGTCCYGTTCGACCGGGCTCTTCTACAATTTGTTTTTCATTCT |

| 22223333333444444444444444444444444444444444444444455555555 | |

| 00024689999000111111222222233333345566666677788889900134555 | |

| 25609283789479146789012567801236950303678902306788949265237 | |

| 1 | TCGGGGGGCGC-CCCACTCCTGGTGGTCGTCACGAGGCCGCAGGCCCGCACGTCGGCGC |

| 2 | TCGGGGGGCGCCCCCACTCCTTGTGCTCGTCATGAGGCCGCGGGCCCGCACGTCGGCGC |

| 3 | CTGGGCGGCGCAACTTTCCACTTGGCTTGCGCGGTGGATGCATGCCAGCACGTCGAC-- |

| 4 | TCGGGGGGCGC-ACTATCCTTCCGACTCGCATTGAGGTTGTGGATCAACGTTTTGGCGC |

| 5 | CTGGGGGGCGC-ACCATCCTTGCGATTCGCATGGAGGCTGTGGATCAACGTTTCGGCGC |

| 6 | CCGGGGGGCGC-ACCATCCTCAGGACTCGCATGGAGGCTGTGGATCAACGTTTCGACGC |

| 7 | CCAGAGGGCGC-ACCTTCCTTACGATTCGCATGGAGGCTGTGGATCAACGTTTCGGTGT |

| 8 | CCGGGGGGCGCCACCATCCTTGCGACTTTCGTGGAAGCTGTGGGTTAACGTTTCGGCGC |

| 9 | TCGGGGGTTGCTAT-----------------TGGAAGCTGTGAATCAACGTTCTGGCGC |

| 10 | TCGGGGGTTGCTAT-----------------TGGAAGCTGTGAATCAACGTTCTGGCGC |

| 11 | TCGGGGGTTGCTAT-----------------TGGAAGCTGTGAATCAACGTTCTGGCGC |

| 12 | CCGGGGGGCGTCAT-----------------TGGAAGCTGTGGATCAATGTTCTGGTGC |

| 13 | CCGGAGGTCACCAT-----------------TGGAAGTTGTGGATCAACGTTCTGGCGC |

| 14 | CCGAGGGGCGACACCATCCTCACGGCTCGCATGGAGGCTGCGGATCAAAGTTCTAGCGT |

| 15 | CCGGGRGGCG-CACTATCCTTGCGACTCACGTGGTAGCTGTGGATTAACGTTCTGGCGC |

| 16 | CCGGGGGTTGTCACCATCTTT--GACTCACATGATAGCTATGGGTCAATGTTCTGGCAC |

| 17 | CCGGGGGTTGTCACCATCTTT--GACTCACATGATAGCTATGGGTCAATGTTCTGGCAC |

| 18 | CCGGGGGTTGCCACCATCTTT--GACTCACATGATAGCTATGGGTCAATGTTCTGGCAC |

| 19 | CCGGGGGTTGCCACCATCTTT--GACTCACATGATAGCTATGGGTCAATGTTCTGGCAC |

| 20 | CCGGGAGACG-CACCATCCTTACAATTCGCACGGAAGCTGCGGATCAAAGTTCTAGTG- |

| 21 | CCGGGGGGCG-CACTATCCTTTCGAACCACATGGAATCTGTGGATTAACGTTCTGGCGT |

| 22 | CYAGGGGGCG-CACCATCCTTGCGAACCGCATGGAATCTGTGGATTAACGTTCTGGCGT |

| 23 | CCGGGGGGCG-CACCATCCTTGCGACTCGCATGGAATCTCTGGATTAACGTTCTGGCGT |

| 24 | CCGGGGGGCGACACCATCCTCACGACTTGCATGGAAGCTGCGGATCAAAGTTCTAGCGC |

| 25 | CCGGGGATCACCAT-----------------TGGAAGCTGTGGATCAACGTTCTGGCGC |

| 26 | CCGAGGGGCGACACCATCTTCACGGCTCGCATGGAAGCTGCGGATCAAAGTTCTAGCGT |

| 27 | CCGGGGGGCG-CACCATCCTTGCGACTCGCATGGAATCTGTGGATTAACGTTCTGGCGT |

| 28 | CCGGGGGGCG-CACCATCCTTGCGACCCGCATGGAATCTGTGGATTAACGTTCTGGCGT |

| 29 | CCGGGGGGCG-CACCATCCTTGCGACCCGCATGGAATCTGTGGATTAACGTTCTGGCGT |

| 30 | CCGGGAAGCG-CACCATCCTCACGATTCGCATGGAAACTGCGGATCAAAGTTCTAGTGC |

| 31 | CCGGGGGGCGACACCATCCTCACGACTCGTCTGGAAGCTGCGTATCAAAGTTCTAGCGT |

| 555555555555666666 | |

| 566677788889000122 | |

| 814601923689258067************** | |

| 1 | GCCCCTCGCAGGGAACCC11111121122121 |

| 2 | GCCCCTCGCCGGGAACCC11111111122121 |

| 3 | ------CGCAGGGAGTCC11111111222121 |

| 4 | GCCTCCCTCAGGACAACC11122121222112 |

| 5 | ACCTCCCTAAGGACAACC21122121222112 |

| 6 | GTCKCCCTCAGGACAACC11122121122112 |

| 7 | GCCTCCCTCAGGACAACT11122121122212 |

| 8 | GTCTCCCTCAGGACAACC11122111122112 |

| 9 | ATCTCCCTCAGTACAACC11222112122112 |

| 10 | ATCTCCCTCAGTACAACC11222112122112 |

| 11 | ATCTCCCTCAGTACAACC11222112122112 |

| 12 | ATCTCCTTCAGTACAACC11222112122112 |

| 13 | ATCTCCCTCAGTACAACC12122112122112 |

| 14 | GCCTCCCTCAGTACAACC13122111222212 |

| 15 | ATCTTCCTCAGTACAACC14222211122112 |

| 16 | ATCTTCCTCGGTACAATC15222113222112 |

| 17 | ATCTTCCTCAGTACAATC15222113222112 |

| 18 | ATCTTTCTCAGTACAATC15222113221112 |

| 19 | GTCTTCCTCAGTACAATC15222113222112 |

| 20 | ACCTCCCTCAGTAAAACC16122211222212 |

| 21 | GCTTCCCCCATGACAACC11122211212112 |

| 22 | GCTTCCCCCATGACAACC11122211212112 |

| 23 | GCCTCCCACATGACAACC11122211222112 |

| 24 | GCCTCTCTCAGTACAACT11122111222212 |

| 25 | ATCTCCTTCAGTACAACC12222112122112 |

| 26 | GCCTCCCTCAGTACAACC13122111222212 |

| 27 | GCCTCCCCCATGACAACC11122211222112 |

| 28 | GCCTCCCCCATGACAACC21122211211112 |

| 29 | GCCTCCCCCATGACAACC11122211222112 |

| 30 | GCCTCCCTCAGTAAAACC16122211222212 |

| 31 | GCC-TCCTACCTATGANN11122111221112 |

Numbers along top of matrix are informative site positions in the aligned ITS region sequences, with the origin at the ITS1 site bordering the 18S cistron. The last 14 characters, marked by asterisks, are recoded indels. Numbers along the left border of the matrix refer to individual samples or reconstructed ancestral sequences of species or populations. All samples are from California, (and are deposited at the Jepson Herbarium) unless otherwise indicated: 1 = Eryngium cervantesii, Mexico, LC 2443 (UC); 2 = E. mexicanum, Mexico, LC 2428 (UC); 3 = Astrantia major, France, 1996, J. L. Benito s. n. (JACA); 4 = Sanicula orthacantha, China, 1980, B. Bartolomew et al. s. n. (UC); 5 = S. europaea, Spain, P. Catalán 1896 (JACA); 6 = S. chinensis, China, 1984, S. N. Kobayashi s. n. (MAK); 7 = S. elata, Malaysia, J. H. Beaman 9108 (UC); 8 = S. canadensis, North Carolina, U.S., BGB 919b, (UC); 9 = S. mariversa, Oahu, Hawaii, K. M. Nagata 3171 (UC); 10 = S. sandwicensis, East Maui, J. Henrickson & R. Vogl 3635 (UC), Hawaii, R. Gustafson 2408 (RSA); 11 = S. purpurea, West Maui, S. Meidell 113 (UC); 12 = S. arctopoides, San Francisco Co., 1PV96, Sonoma Co., 7PV96, Del Norte Co., 34PV96; 13 = S. arguta, San Clemente Island, S. Boyd 4435 (RSA), San Luis Obispo Co., 19PV96, San Diego Co., 26PV96; 14 = S. bipinnatifida, San Diego Co., 25PV96, San Luis Obispo Co., 14PV96, Siskiyou Co., 38PV96; 15 = S. bipinnata, Monterey Co., 12PV96, Santa Barbara Co., 28PV96; 16 = S. crassicaulis, El Dorado Co., 47PV96, Marin Co., 17PV96; 17 = S. crassicaulis, Chile, D. M. Moore 225 (UC); 18 = S. crassicaulis, Santa Barbara Co., 29PV96; 19 = S. crassicaulis, Alameda Co., 18PV96, Marin Co., 16PV96; 20 = S. deserticola, Baja California, Mexico, RM 19353 (UC); 21 = S. graveolens, Placer Co., 45PV96; 22 = S. graveolens, Chile, M. L. DeVore 1144 (UC); 23 = S. graveolens, San Diego Co., 23PV96; 24 = S. hoffmannii, San Luis Obispo Co., 20PV96, 21PV96, Santa Barbara Co., 27PV96; 25 = S. laciniata, Mendocino Co., 31PV96, Monterey Co., 9PV96, San Luis Obispo Co., 13PV96; 26 = S. peckiana, Del Norte Co., 35PV96, 37PV96; 27 = S. tuberosa, Butte Co., 41PV96, Marin Co., 3PV96, San Diego Co., 24PV96, Shasta Co., 40PV96, Trinity Co., 42PV96; 28 = S. saxatilis, Contra Costa Co., BGB 905, Santa Clara Co., 10PV96; 29 = S. tracyi, Humboldt Co., 32PV96, Trinity Co., 33PV96; 30 = S. moranii, Baja California, Mexico, RM 21252 (UC), RM 23279 (SD); 31 = S. maritima, Monterey Co., 15PV96, San Luis Obispo Co., 22PV96. Acronyms in parentheses are standard herbarium abbreviations in Index Herbariorum. Abbreviations: Co., County; LC, Lincoln Constance; BGB, Bruce Baldwin; PV, Pablo Vargas; RM, Reid Moran.

Total DNAs were extracted from pooled fresh leaf tissue of 5–10 individuals per population or from dried leaf fragments of herbarium specimens by using a modification of the hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method in Doyle and Doyle (12), with two ethanol precipitations. The 18S–26S nuclear rDNA ITS region (ITS1, 5.8S subunit, and ITS2) was PCR-amplified by using c28kj (5′-TTGGACGGAATTTACCGCCCG-3′, designed by K. W. Cullings, San Francisco State University) and LEU1 (5′-GTCCACTGAACCTTATCATTTAG-3′, designed by L. E. Urbatsch, Louisiana State University) for most samples. The internal primers ITS2, ITS3, ITS4, and ITS5 (13) were used for sequencing reactions and for PCR amplifications of some genomic DNAs. PCR conditions followed Baldwin (5), modified for symmetric amplification (with equimolar primer concentrations) with a Perkin–Elmer model 9600 thermal cycler. Sequencing reactions and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of sequencing products were conducted by using the Perkin–Elmer/Applied Biosystems Prism Dye Terminator cycle sequencing kit (half-reactions) and a Perkin–Elmer/Applied Biosystems model 377 automated sequencer. Complete sequences of both strands of each PCR product were processed, aligned, and visually checked by using Perkin–Elmer sequence analysis and sequence navigator software.

ITS sequences of all samples were aligned unambiguously into a sequence matrix by visual inspection. Phylogenetic analysis of the data matrix was conducted by using Fitch parsimony (using test version 4.0d55 of paup*, written by D. L. Swofford, Smithsonian Institution), with equal weighting of all character transformations. The heuristic search strategy involved 20 analyses with “random” addition sequences of the taxa, mulpars, and tree bisection and reconnection (TBR) branch swapping with steepest descent in effect. Inferred insertion/deletion (indel) mutations were treated as either missing data or were recoded as additional characters for different analyses. Indels were recoded as binary characters (presence/absence) or, in one ITS1 region of overlapping indels, as a multistate character.

An initial heuristic search and a bootstrap analysis (using “fast” stepwise addition, in paup*) were performed including sequences of all 54 samples listed in Table 1. To improve search capability, monophyletic groups of conspecific ITS sequences resolved in the initial search (most of which were resolved in >90% of the 1,000 bootstrap replicates) were compartmentalized (14) into single archetype sequences (except for Sanicula crassicaulis and Sanicula graveolens—compartmentalization was carried as far as possible in each of the two species without merging North American and South American samples) by using macclade version 3.01 (15) to reconstruct ancestral states. If equivocal, ancestral states were coded as polymorphic by using International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry ambiguity symbols (a net reduction in ambiguously coded states resulted from compartmentalization). The resulting 31 sequences were used exclusively in subsequent searches and analyses of clade reliability.

Reliability of lineages was assessed by using bootstrap (100 resamplings of the data) and decay-index analyses using a heuristic search strategy with closest addition sequence of the taxa, mulpars, and TBR branch swapping with steepest descent implemented. Historical biogeographic patterns were examined on the maximally parsimonious trees by using the character evolution reconstruction function of macclade (15).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

ITS Sequence Variation.

Alignment of the 31 sequences studied in detail generated a matrix of 628 characters, 136 of which are potentially informative for parsimony analysis (63 of 226 characters in ITS1, 3 of 163 characters in 5.8S subunit, and 70 of 239 characters in ITS2; see Table 1). Inferred indels were recoded as 14 additional informative characters (5 in ITS1 and 9 in ITS2; see Table 1). No evidence of divergent paralogous ribosomal DNA copy types was found in any of the species studied.

Phylogenetic Resolution.

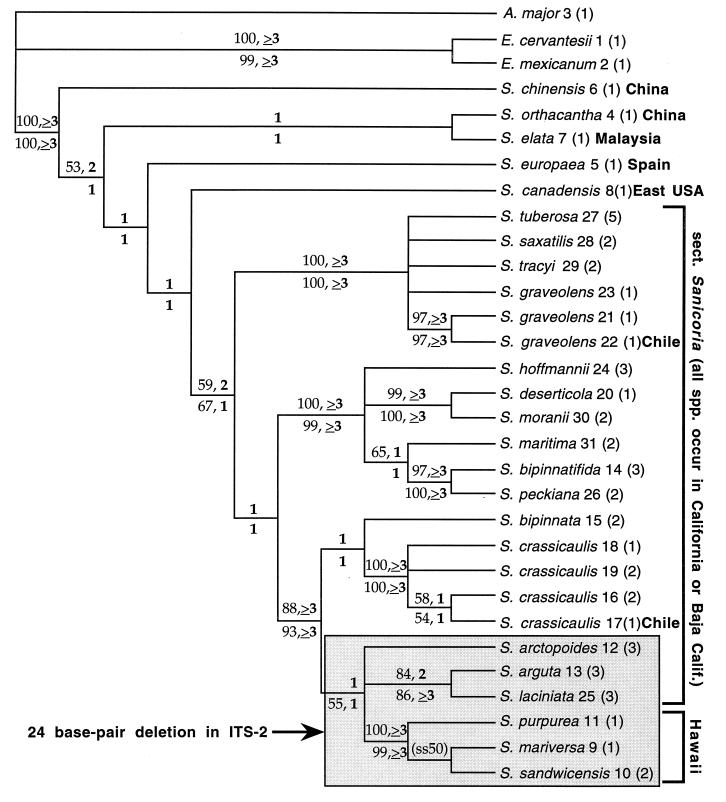

The pattern of diversification resolved in all maximally parsimonious trees indicates that the western American and Hawaiian species of S. sect. Sanicoria and S. sect. Sandwicenses constitute a monophyletic group comprising three well-supported lineages (Fig. 1). Based on the ITS trees, the Hawaiian species form a monophyletic group with three species from the Pacific Coast of North America: Sanicula arctopoides, Sanicula arguta, and Sanicula laciniata. The lineage comprising the Hawaiian taxa and the three western North American species, although weakly supported by nucleotide substitution data, is well-diagnosed by a 24-bp ITS2 deletion (see Fig. 1). The semistrict consensus of minimum-length trees reconstructed from analysis of the entire data matrix (including recoded indels) is entirely congruent with, but less resolved than, the consensus tree shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Semistrict consensus of 252 minimum-length Fitch parsimony trees of nuclear ribosomal DNA ITS sequences in Sanicula and outgroups, without recoding of insertions/deletions (indels) as additional characters (consistency index = 0.74; retention index = 0.79). The same island of 252 trees was found in each of the 20 heuristic analyses, with random addition sequences of the taxa. Numbers immediately after species names refer to numerically designated sequences in Table 1. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of populations sampled. Numbers above tree branches are bootstrap (standard type) and decay (boldface type) values from analyses of the data matrix (Table 1) with recoded indel characters excluded. Numbers below tree branches are bootstrap (standard type) and decay (boldface type) values from analyses of the data matrix (Table 1) including the recoded indel characters. Only bootstrap values above 50% are shown. A., Astrantia; E., Eryngium; S., Sanicula. (ss50) indicates the only branch not resolved in the strict consensus of minimum-length trees; the branch was resolved in 50% of the minimum-length trees and in the semistrict consensus tree.

Each taxon represented by multiple populations was resolved as monophyletic in the initial parsimony analysis except S. graveolens, one sample of which formed a polytomy with four other lineages in the semistrict consensus tree: Sanicula saxatilis, Sanicula tracyi, Sanicula tuberosa, and other populations of S. graveolens. South American samples of the only species in S. sect. Sanicoria that occur outside western North America, S. crassicaulis and S. graveolens, were placed within lineages also containing Californian populations of the two taxa (Fig. 1).

Biogeographic Implications.

The Hawaiian S. sect. Sandwicenses and South American populations of S. sect. Sanicoria are highly nested within a lineage of species that are mostly confined to the California Floristic Province (Fig. 1). In S. sect. Sanicoria, only Sanicula deserticola, of Baja California, is not found within the California Floristic Province (16). Historical biogeographic reconstructions based on the maximally parsimonious trees provide support for three long-distance dispersal events from western North America: one to the Hawaiian archipelago and two (S. crassicaulis and S. graveolens) to southern South America.

Origin of the Hawaiian lineage must have involved a single-step dispersal event of intercontinental magnitude. Ocean-floor spreading along the mid-Atlantic ridge has placed North America and the Hawaiian Islands closer to each other at present (at about 3,900 km) than at any time in the past (17–19). Furthermore, no geological evidence exists for now-extinct islands that could have served as “stepping-stones” for dispersal from North America to the Hawaiian archipelago. The distance between North American and South American populations of S. crassicaulis and S. graveolens, and the Mediterranean climatic regions in which they occur, is much greater than the oceanic barrier between North America and the Hawaiian Islands. Calibration of the S. sect. Sanicoria + S. sect. Sandwicenses clade at the maximum age conceivable for neoendemic Californian plant radiations [i.e., at 15 million years ago (Ma), the onset of late Tertiary summer drying in western North America; see ref. 20] in a rate-constant ITS tree of Sanicula (tested by using likelihood functions in paup*, with exclusion of Sanicula maritima; P.V., B.G.B., and M. J. Sanderson, unpublished results) yields maximum ages of about 1 Ma for the Hawaiian clade, about 1 Ma for South American S. crassicaulis, and about 2 Ma for South American S. graveolens (P.V., B.G.B., and M. J. Sanderson, unpublished results). These preliminary results support Raven’s suggestion (21) that amphitropical dispersal in Sanicula probably occurred since the mid-Pliocene.

Dispersal of Sanicula to the Hawaiian Islands and South America was likely bird-mediated (see ref. 22). All members of the sublineage to which the Hawaiian species and South American S. crassicaulis belong (also including S. arctopoides, S. arguta, Sanicula bipinnata, and S. laciniata) possess fruits covered with hooked prickles (7). S. graveolens also bears fruits with hooked prickles that may have promoted external bird dispersal to South America (23). Within the sublineage that includes S. saxatilis, S. tracyi, and S. tuberosa, only S. graveolens possesses prickly fruits and has a distribution that extends beyond the California Floristic Province (7, 23, 24). Regular sightings of North American migratory birds and “accidentals” in the Hawaiian Islands (25) and regular migration of various species of Charadriiformes (shore birds) between California and Chile/Argentina (26) illustrate the potential for long-distance dispersal of the type inferred herein. Establishment of S. crassicaulis in South America would have been promoted by its strong propensity for selfing, unlike other studied species in S. sect. Sanicoria (8). Numerous other examples of apparently conspecific or closely related angiosperms and ferns show a similar disjunct pattern between temperate regions of western North America and southern South America (21). Most of the amphitropical disjunctions have been inferred to have arisen by dispersal from North America (see refs. 21, 23, 27–29), as confirmed herein for Sanicula and in other molecular phylogenetic studies for groups such as Microseris sect. Microseris (Compositae) (30), Epilobium sect. Boisduvalia (Onagraceae) (31), and Gilia (Polemoniaceae) (32).

Although origin of South American S. crassicaulis and S. graveolens from western North American ancestors was previously hypothesized by Constance (23) and Raven (21), origin of the Hawaiian sanicles has remained uncertain. Shan and Constance (7) concluded that the Hawaiian species constitute a natural group, in accord with our results showing that the species stem from a single common ancestral species in the Hawaiian archipelago. Froebe (33) postulated that the Hawaiian species resulted from two colonizations of the Hawaiian Islands by North American ancestors in S. sect. Sanicoria. Froebe’s hypothesis (33) of a close relationship between the western American S. sect. Sanicoria and Hawaiian S. sect. Sandwicenses was based on his interpretation that members of both groups possess a taproot, a putative shared derived characteristic. A preliminary morphological phylogenetic analysis of Sanicula did not resolve the closest relationships of the Hawaiian species (P.V., B.G.B., L.C., and B. D. Mishler, unpublished results). Combined analysis of the morphological and molecular data yielded a tree topology congruent with the ITS trees with respect to relationships of the western American and Hawaiian species (P.V., B.G.B., L.C., and B. D. Mishler, unpublished results).

Our results demonstrate that the origin of Hawaiian species of Sanicula provides a remarkable parallel to the origin of the Hawaiian silversword alliance (Asteraceae—Madiinae; refs. 4–6, 34, and 35), i.e., a second example of a diverse Hawaiian lineage that arose from within a radiation of herbaceous species centered in the California Floristic Province. Phylogenetic verification of the origin of the two southern South American sanicles reinforces the hypothesis (see refs. 22 and 26) that western North America has served as a floristic source area for climatically similar areas far to the south. Although California may be considered a floristic island, our data from Sanicula provides additional evidence that California plant lineages have spawned new lines of evolution in other island and island-like areas outside North America.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jose Luis Benito, Pilar Catalán, Jim Jacoby (National Biological Service), Vernon Oswald, and the Maui Pineapple Company (Randall Bartlett and Scott Meidell) for field assistance; the herbarium curators/collection managers of the Bishop Museum (BISH), the California State University at Chico (CHSC), Humboldt State University (HSC), the Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden (RSA), the San Diego Natural History Museum (SD), and the University Herbarium (UC) of the University of California at Berkeley for providing loans of Sanicula specimens; Brent Mishler and Mike Sanderson for constructive advice; Peter Raven for expeditious editorship; John Strother and four anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on earlier versions of the manuscript; and Bridget Wessa for technical assistance. This research was supported by awards from the Lawrence R. Heckard Endowment Fund of the Jepson Herbarium (to P.V.) and the National Science Foundation (DEB-9458237, to B.G.B.) and by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science (to P.V.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- ITS

internal transcribed spacer of 18S–26S nuclear ribosomal DNA

- Ma

million years ago

Footnotes

References

- 1.Wagner W L, Funk V A, editors. Hawaiian Biogeography: Evolution on a Hot Spot Archipelago. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wagner W L. In: The Unity of Evolutionary Biology, The Proceedings of the Fourth International Congress of Systematics and Evolutionary Biology. Dudley E C, editor. Vol. 1. Portland, OR: Dioscorides; 1991. pp. 267–284. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fosberg F R. In: Insects of Hawaii: Introduction. Zimmerman E C, editor. Honolulu, HI: Hawaii Univ. Press; 1948. pp. 107–119. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baldwin B G, Kyhos D W, Dvorak J, Carr G D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1840–1843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baldwin B G. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1992;1:3–16. doi: 10.1016/1055-7903(92)90030-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baldwin B G. In: Compositae: Systematics, Proceedings of the International Compositae Conference, Kew, 1994. Hind D J N, Beentje H J, editors. Kew, U.K.: Royal Botanic Gardens; 1996. pp. 377–391. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shan R H, Constance L. Univ Calif Publ Bot. 1951;25:1–78. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell C R. Univ Calif Publ Bot. 1954;27:133–230. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Constance L. In: Manual of the Flowering Plants of Hawai‘i. Wagner W L, Herbst D R, Sohmer S H, editors. Honolulu, HI: Univ. of Hawaii Press and Bishop Museum Press; 1990. pp. 208–210. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vargas, P., Constance, L. & Baldwin, B. G. (1998) Brittonia 50, in press.

- 11.Plunkett G M, Soltis D E, Soltis P S. Syst Bot. 1996;21:477–495. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doyle J J, Doyle J L. Phytochem Bull Bot Soc Amer. 1987;19:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 13.White T J, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J. In: PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications. Innis M, Gelfand D, Sninsky J, White T, editors. San Diego: Academic; 1990. pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mishler B D. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1994;94:143–156. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330940111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maddison W P, Maddison D R. MacClade: Analysis of Phylogeny and Character Evolution. Version 3.0. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raven P H, Mathias M E. Madroño. 1960;15:193–197. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson J T, editor. Readings from Scientific American: Continents Adrift and Continents Aground. San Francisco: Freeman; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dalrymple G B, Silver E A, Jackson E D. Am Sci. 1973;61:294–308. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clague D A, Dalrymple G B. In: Volcanism in Hawaii. Decker R W, Wright T L, Stauffer P H, editors. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1987. pp. 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baldwin B G. In: Molecular Evolution and Adaptive Radiation. Givnish T J, Sytsma K J, editors. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge Univ. Press; 1997. pp. 103–128. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raven P H. Quart Rev Biol. 1963;38:151–177. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carlquist S. Bull Torrey Bot Club. 1967;94:129–162. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Constance L. Quart Rev Biol. 1963;38:109–116. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Constance L. The Jepson Manual: Higher Plants of California. Berkeley, CA: Univ. Calif. Press; 1993. pp. 162–164. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shallenberger R J, editor. Hawaii’s Birds. Honolulu, HI: Hawaiian Audubon Soc.; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cruden R W. Evolution. 1966;20:517–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1966.tb03383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heckard L R. Quart Rev Biol. 1963;38:117–123. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chambers K L. Quart Rev Biol. 1963;38:124–140. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ornduff R. Quart Rev Biol. 1963;38:141–150. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wallace R S, Jansen R K. Syst Bot. 1990;15:606–616. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baum D A, Sytsma K J, Hoch P C. Syst Bot. 1994;19:363–388. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Porter J M. Aliso. 1997;15:57–77. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Froebe H A. Bot Jahrb Syst. 1971;91:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carlquist S. Aliso. 1959;4:171–236. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carr G D, Baldwin B G, Kyhos D W. Am J Bot. 1996;83:653–660. [Google Scholar]