Abstract

Experiments were performed under Saffan anaesthesia on normoxic (N) rats and on chronically hypoxic rats exposed to 12% O2 for 1, 3 or 7 days (1, 3 or 7CH rats): N rats routinely breathed 21% O2 and CH rats 12% O2. The 1, 3 and 7CH rats showed resting hyperventilation relative to N rats, but baseline heart rate (HR) was unchanged and arterial blood pressure (ABP) was lowered. Femoral vascular conductance (FVC) was increased in 1 and 3CH rats, but not 7CH rats. When 1–7CH rats were acutely switched to breathing 21% O2 for 5 min, ABP increased and FVC decreased, consistent with removal of a hypoxic dilator stimulus that is waning in 7CH rats. We propose that this is because the increase in haematocrit and vascular remodelling in skeletal muscle help restore the O2 supply. The increases in FVC evoked by acute hypoxia (8% O2 for 5 min) and by infusion for 5 min of α-calcitonin gene-related peptide (α-CGRP), which are NO-dependent, were particularly accentuated in 1CH, relative to N rats. The NO synthesis inhibitor l-NAME increased ABP, decreased HR and greatly reduced FVC, and attenuated increases in FVC evoked by acute hypoxia and α-CGRP, such that baselines and responses were similar in N and 1–7CH rats. We propose that in the first few days of chronic hypoxia there is tonic NO-dependent vasodilatation in skeletal muscle that is associated with accentuated dilator responsiveness to acute hypoxia and dilator substances that are NO -dependent.

Acute systemic hypoxia evokes an increase in ventilation, heart rate (HR) and vasodilatation in skeletal muscle, although the hyperventilation and HR may wane when the period of hypoxia is maintained (Dempsey & Forster, 1982; Rowell et al. 1989; Thomas & Marshall, 1994; Marshall, 1999; Gonzalez-Alonso et al. 2001). The peripheral vasodilatation generally leads to a fall in arterial blood pressure (ABP) in the rat (see Thomas & Marshall, 1994) and in human subjects also, when the hypoxia is severe (Rowell et al. 1989). The vasodilatation in skeletal muscle is partly mediated by adenosine acting on A1 receptors (Thomas et al. 1994; Bryan & Marshall, 1999a). However, nitric oxide (NO) makes an even larger contribution: inhibition of NO synthase (NOS) decreased baseline femoral vascular conductance (FVC), reflecting removal of the tonic dilator influence of NO and virtually abolished the increase in FVC evoked by hypoxia in the rat and human subjects (Blitzer et al. 1996; Skinner & Marshall, 1996; Bryan & Marshall, 1999b). Current evidence indicates this arises firstly because the dilator influence of adenosine is partly mediated by NO and a tonic level of NO is required for adenosine to be released from the endothelial cells by hypoxia (Ray et al. 2002; Edmunds et al. 2003; Ray & Marshall, 2005). Secondly, it is likely that NO synthesis is required for that part of the action of adenosine and of other dilator substances released in systemic hypoxia, such as adrenaline, that rely on an increase in cAMP (see Mian & Marshall, 1991; Edmunds et al. 2003). For cGMP and cAMP are synergistic in producing vasodilatation, and thus a decrease in cGMP induced by inhibition of NOS not only reduces vasodilatation evoked by agonists that act via NO, but those that act by increasing cAMP (de Wit et al. 1994).

Substantial adaptations occur in chronic systemic hypoxia. Thus, within 3–4 weeks of chronic hypoxia there is resting hyperventilation and an increase in haematocrit (Hct; Olson & Dempsey, 1978; Dempsey & Forster, 1982; Ou et al. 1992). Somewhat surprisingly, ABP may be similar, or raised relative to levels recorded in normoxic individuals, while FVC may be similar, or lowered relative to normoxic individuals (Kuwahira et al. 1993; Thomas & Marshall, 1997; Hansen & Sander, 2003; Coney et al. 2004). These findings may be explained by the fact that the hyperventilation and raised Hct, together with angiogenesis, which is characterized by an increase in the number of arterioles and in capillary: fibre ratio, restore the tissue oxygen supply of muscle towards the normoxic level, so alleviating the local dilator influences of hypoxia (Price & Skalak, 1998; Smith & Marshall, 1999; Deveci et al. 2001).

Chronic hypoxia is also associated with changes in vascular responsiveness. Thus, in rats acclimated to breathing 12% O2 for 3–4 weeks (3–4 week CH rats), muscle vasculature shows greater dilator responsiveness to acute hypoxia (breathing 8% O2) than normoxic (N) rats (Mian & Marshall, 1996; Thomas & Marshall, 1997). On the other hand, muscle vasoconstrictor responses to sympathetic nerve activity and exogenous noradrenaline are blunted in 3–4 week CH rats (Doyle & Walker, 1991; Marshall, 2001; Coney et al. 2004) and in chronically hypoxic humans (Heistad & Wheeler, 1970; Hansen & Sander, 2003). These changes are partly attributable to a greater dilator influence of adenosine and NO (Mian & Marshall, 1996; Marshall, 2001; Bartlett & Marshall, 2003).

The time course and mechanisms underlying the respiratory and Hct adaptations to chronic hypoxia have been investigated (see Olson & Dempsey, 1978; Dempsey & Forster, 1982; Ou et al. 1992). By contrast, little is known of the accompanying cardiovascular changes. Arteriolar remodelling is already present in rats exposed to chronic hypoxia for 7 days (7CH rats), the increase in arteriolar branching in skeletal muscle leading to an increase in maximal, or structural FVC relative to 7N rats. At this time, there is also evidence of increased dilator responsiveness to acute hypoxia (Smith & Marshall, 1999). Moreover, even 2CH rats show blunted mesenteric vasoconstrictor responses to phenylephrine, and in mesenteric resistance arteries ex vivo, these constrictor responses were partly restored by NOS inhibition (Gonzales & Walker, 2002), suggesting that the dilator influence of NO may already be accentuated.

Thus, a primary objective of the present study was to compare the baseline status of the respiratory and cardiovascular systems, including muscle vasculature, in 1, 3 and 7CH rats with those of N rats. Male rather than female rats were used, to avoid the effects of cyclical changes in hormone levels. We compared baselines when CH rats were breathing 12% O2 and N rats were breathing 21% O2 and monitored the changes when CH rats were acutely switched to 21% O2 and N rats to 12% O2, to assess the extent to which adaptation had taken place. We hypothesized that NO exerts a greater dilator influence in 1–7CH rats than in N rats. Thus, we tested the effect of NOS inhibition on baselines and on responses evoked by acute hypoxia produced by switching CH and N rats from breathing 12 and 21% O2, respectively, to 8% O2. We further hypothesized that muscle vasodilator responses to agonists whose action is NO dependent are accentuated in 1–7CH rats relative to N rats. Thus, we compared responses evoked by α-calcitonin gene-related peptide (α-CGRP) before and after NOS inhibition: muscle vasodilatation evoked by α-CGRP is largely NO dependent (Gardiner et al. 1991) and likely to be mediated by cGMP and cAMP (Kubota et al. 1985; Wang et al. 1991; Fiscus et al. 1994).

Methods

All experiments were performed in accordance with the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. Male Wistar rats were kept in either a hypoxic chamber at 12% O2 for 1, 3 or 7 days (1, 3 or 7CH rats) or in similar conditions whilst breathing air (N rats). The CH and N rats were weight matched at the time of the acute experiment. The details of the hypoxic chamber have been described before (Smith & Marshall, 1999; Coney et al. 2004). Briefly, the O2 concentration in the chamber was kept at 12% O2 (range 11.5–12.5% O2) by means of a servo-controlled solenoid valve system that introduced air or N2 into the chamber, the atmosphere being re-circulated at 15 l min−1. The CO2 was scrubbed with soda lime, the humidity was controlled by a refrigeration unit and silica gel column, while the temperature was controlled at ∼22°C (range 21–23°C). Ammonia was removed by means of a molecular sieve. The chamber was opened for ∼10 min every day to allow rats to be introduced or removed and to allow routine animal husbandry.

On the day of the acute experiment, all N and CH rats were brought to the laboratory and anaesthesia was induced and maintained as described before (see Thomas & Marshall, 1994b; Coney et al. 2004). Briefly, anaesthesia was achieved by introducing 3.5% halothane in O2 into a small box containing the rat. When the animal was anaesthetized, as judged by loss of withdrawal reflexes, it was placed on an operating table. Gaseous anaesthesia was maintained by means of 2.5% halothane in O2, delivered via a nose cone and a cannula was placed in the right jugular vein. The gaseous anaesthesia was withdrawn and anaesthesia was maintained by continuous infusion of the steroid agent, Saffan (Schering-Plough at 7–12 mg kg−1 h−1, i.v.). A T-shaped tracheal cannula was then quickly inserted. The side arm was connected by tubing to a rotameter system that allowed N2 and O2 from cylinders to be mixed and delivered at ∼1 l min−1. By this means, the N rats breathed 21% O2 in N2 and the CH rats breathed 12% O2 in N2 throughout the experiment, except when the mixtures were changed as part of the protocol (see below). The time that elapsed between the CH rats leaving the hypoxic chamber and beginning to breathe 12% O2 from the rotameter system was < 1 h.

The rats were then prepared for recording physiological variables as described before (see Coney et al. 2004). A cannula was then placed in the left brachial artery to allow ABP to be recorded via a pressure transducer. The left femoral artery was cleared to allow femoral blood flow to be recorded via a transonic probe (0.7 V) connected to a meter (T106, Transonic Systems Inc., Icatha, NY, USA). The right femoral artery was cannulated to allow (100 μl) arterial blood samples to be removed for analysis of the partial pressures of O2 and CO2 (PaO2, PaCO2, respectively) and arterial pH (pHa) by means of a Nova Stat Profile 3 analyser (Stat 3, V.A., Hove, MA, USA). Samples of 80 μl were also withdrawn into a capillary tube to allow measurement of Hct: the tubes were centrifuged at 11 800 rotations min−1at 16 060 g for 5 min: Hct was expressed as a percentage. In addition, the ventral tail artery was cannulated with tubing that was inserted so that its tip lay at the bifurcation of the dorsal aorta as determined post mortem. This cannula allowed preferential administration of pharmacological agents into the left hindlimb from which femoral blood flow (FBF) was recorded.

Finally, the tubing connected to the side arm of the tracheal cannula was briefly removed so that a pneumotachometer flow head (ADInstruments Ltd) could be attached to the side arm; the tubing was then reconnected to the distal end of the flow head. The flow head allowed continuous measurement of tidal volume (VT) and respiratory frequency (RF).

The output of the arterial pressure transducer, flow meter and flow head were fed into a MacLab/8s data acquisition system which was connected to an Apple Macintosh G3 computer; cardiovascular and respiratory variables were sampled at 100 and 40 Hz, respectively. Heart rate (HR) and mean ABP (MABP) were derived from the ABP signal, while femoral vascular conductance (FVC) was computed on line as FBF/ABP.

Protocols

When all the surgery had been completed, the infusion rate of Saffan was reduced to 4–8 mg kg−1 h−1 adjusted for each animal, so that a new stable level of anaesthesia was achieved at which there was, at most, a sluggish withdrawal reflex and no spontaneous, transient changes in ABP or HR. We have previously shown that Saffan anaesthesia maintained in this way preserves autonomic control of the cardiovascular system, including that exerted from the forebrain. In particular, it allows cardiovascular responses to acute hypoxia that are qualitatively similar to those evoked in unanaesthetized, instrumented rats: the major disparity is that the local vasodilator influences of hypoxia are stronger in Saffan-anaesthetized rats and so the fall in ABP is greater (Marshall & Metcalfe, 1990; Marshall, 1999).

The respiratory and cardiovascular variables were then allowed to stabilize for at least 30 min so that baseline values could be recorded. At the end of this period, arterial blood samples were removed for analysis of PaO2, PaCO2, pHa and Hct. Different protocols were then performed on two groups each of N and CH rats. At the end of the experiment all animals were killed by an overdose of anaesthetic.

Group 1

These experiments were performed on ten N rats (body weight 200 ± 14 g, mean ± s.e.m.) and nine each of 1, 3 and 7CH rats (208 ± 10, 211 ± 16 g and 215 ± 8 g, respectively). At the end of the 30 min equilibration period, N rats breathed 12% O2 for 5 min and CH rats breathed 21% O2 for 5 min. Before, and in the 5th minute of each stimulus, a blood sample was removed for analysis of PaO2, PaCO2 and pHa.

Group 2

These experiments were performed on nine N rats (210 ± 9 g), eight 1CH rats (200 ± 12 g), seven 3CH rats (204 ± 13 g) and eight 7CH rats (209 ± 9 g). At the end of the 30 min equilibration period, N and CH rats breathed 8% O2 for 5 min. Baselines were allowed to stabilize for 15–20 min, then α-CGRP was infused for 5 min via the ventral tail artery (6 μmol h−1) whilst the N rats breathed 21% O2 and the CH rats breathed 12% O2. This dose of α-CGRP was the same as the submaximal dose used by Gardiner et al. (1991) that produced an increase in hindquarters vascular conductance of ∼50%, approximately comparable to the increase in FVC produced by breathing 8% O2 in N rats. Blood samples were taken before and in the 5th minute of breathing 8% O2 and of infusion of α-CGRP, for analysis of PaO2, PaCO2 and pHa. The NOS inhibitor l-nitro arginine methyl ester (l-NAME) was then given via the tail artery at 10 mg kg−1. This dose produces a maximal increase in baseline ABP and decrease in baseline FVC indicating blockade of tonic synthesis of NO (see Skinner & Marshall, 1996). Measurements of all variables were taken 15–20 min after l-NAME so that the effect of NOS inhibition on baselines could be assessed. The responses evoked by 8% O2 and α-CGRP were then re-tested as described above.

Statistical analysis

All results are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. All within- and between-group comparisons of absolute values were made by ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test when appropriate; a P value of < 0.05 was taken to be significant. In addition, the responses evoked by breathing 8% O2 or infusion of α-CGRP were expressed as the difference between the values recorded in the 5th minute of the stimulus and the baseline, and were compared within and between groups by ANOVA and post hoc Bonferroni tests when appropriate.

Results

Group 1

The PaO2, PaCO2 and pHa values for N rats breathing 21% O2 and CH rats breathing 12% O2 are shown in Table 1. In CH rats breathing 12% O2, PaO2 and PaCO2 were lower, while pHa was higher than in the N rats breathing 21% O2. There were no differences between the subgroups of CH rats regarding their levels of hypoxia, hypocapnia or alkalosis. The Hct was significantly greater in 3 and 7CH rats (44 ± 2%, 45 ± 1%, respectively) than in N rats (40 ± 2%, P < 0.05), but was unchanged in 1CH rats (42 ± 3%). There was no significant difference between Hct values in 3 and 7CH rats.

Table 1.

Arterial blood gases and arterial pH values recorded in N rats breathing 21% O2 and in the 5th minute of breathing 12% O2 (above) and in 1, 3 and 7CH rats breathing 12% O2 and in the 5th minute of breathing 21% O2 (below)

| PaO2 | PaCO2 | pHa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N rats | 21% O2 | 12% O2 | 21% O2 | 12% O2 | 21% O2 | 12% O2 |

| N | 88.71 ± 2.35 | 43.75 ± 1.92† | 45.00 ± 1.22 | 33.21 ± 0.61† | 7.34 ± 0.01 | 7.42 ± 0.01† |

| CH rats | 12% O2 | 21% O2 | 12% O2 | 21% O2 | 12% O2 | 21% O2 |

| 1CH | 41.22 ± 1.38*‡ | 89.60 ± 1.24† | 31.18 ± 1.02*‡ | 43.27 ± 1.39† | 7.44 ± 0.01*‡ | 7.36 ± 0.01† |

| 3CH | 40.12 ± 1.71*‡ | 85.73 ± 3.12† | 30.04 ± 0.14*‡ | 40.24 ± 3.12†§ | 7.45 ± 0.02*‡ | 7.37 ± 0.02†§ |

| 7CH | 40.55 ± 1.32*‡ | 86.53 ± 2.62† | 29.66 ± 1.00*‡ | 39.01 ± 2.64†§ | 7.46 ± 0.01*‡ | 7.38 ± 0.01†§ |

All values are shown as mean ± s.e.m. Blood gas values are in mmHg.

P < 0.05: baseline values recorded in N rats breathing 21% O2versus CH rats breathing 12% O2.

P < 0.05: values recorded in 21% O2versus 12% O2 in N or CH rats.

P < 0.05: value recorded in N versus CH rats breathing 12% O2.

P < 0.05: value recorded in N versus CH rats breathing 21% O2.

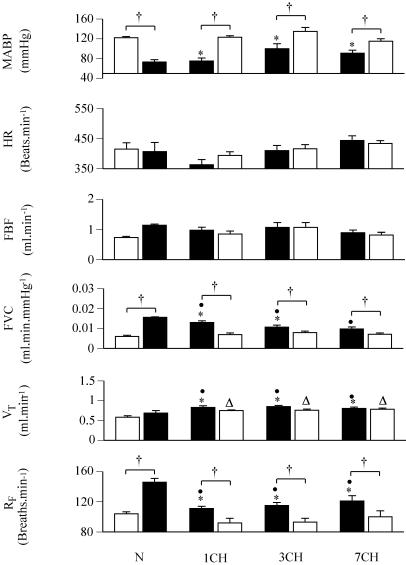

Consistent with the blood gas values, RF and VT were higher in all CH rats breathing 12% O2 than in N rats breathing 21% O2. The HR values were not significantly different between CH and N rats (Fig. 1). On the other hand, MABP was lower in 1, 3 and 7CH rats breathing 12% O2 than in N rats breathing 21% O2. Moreover, FVC was higher in 1 and 3CH rats than in N rats, but was comparable in 7CH and N rats. The net result of the MABP and FVC values was that FBF was not significantly different between N rats breathing 21% O2 and CH rats breathing 12% O2 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Respiratory and cardiovascular responses evoked in normoxic (N rats) by a 5-min period of breathing 12% O2 and in chronically hypoxic rats exposed to 12% O2 for 1, 3 or 7 days (1, 3 and 7CH rats) by a 5-min period of breathing 21% O2.

Groups of rats are indicated below the pairs of columns. In each case, left-hand column indicates value recorded under control conditions (breathing 21% O2 and 12% O2 for N and CH rats, respectively), while right-hand column shows value recorded in 5th minute of breathing 12% O2 and 21% O2 for N and CH rats, respectively. All values are shown as mean ± s.e.m. RF, VT, FVC, FBF, HR and MABP indicate respiratory frequency, tidal volume, femoral vascular conductance, femoral blood flow, heart rate and mean arterial blood pressure, respectively. *P < 0.05: baseline in N rats breathing 21% O2versus CH rats breathing 12% O2. †P < 0.05: baseline versus 5th minute of breathing 12% O2 (N rats) or 21% O2 (CH rats). •P < 0.05: 5th minute of breathing 12% O2 in N rats versus baseline in CH rats breathing 12% O2. ▵P < 0.05: 5th minute of breathing 21% O2 in CH rats versus baseline in N rats breathing 21% O2

Not surprisingly, when N rats were switched from breathing 21% O2 to 12% O2, PaO2 fell and there was a fall in PaCO2 and an increase in pHa (Table 1) concomitant with an increase in RF but no change in VT (Fig. 1). Meanwhile, MABP fell, while FVC increased; there was no significant change in FBF or HR when measured in the 5th minute of breathing 12% O2 (Fig. 1). The consequence of these changes was that in the 5th minute period of 12% O2, the N rats had PaO2 and PaCO2 values that were higher and pHa values that were lower than in CH rats who were continuously breathing 12% O2 (Table 1). This reflected the fact that although the RF values were higher in the N rats at the end of the 5th minute of breathing 12% O2 than in the CH rats breathing 12% O2, the VT values were lower in the N rats than in the CH rats (Fig. 1). The MABP values were not significantly different between the N rats acutely breathing 12% O2 and the CH rats continuously breathing 12% O2, but FVC values were higher in the N rats breathing 12% O2 than in the 1 and 3CH rats (Fig. 1).

When the CH rats were switched from 12% O2 to breathing 21% O2 for 5 min, PaO2 and PaCO2 increased while pHa fell, there being no obvious difference between the subgroups (Table 1). These changes may be attributed to a fall in RF in all three CH groups, for there were no changes in VT by the 5th minute of breathing 21% O2 (Figs 1 and 2). Concomitantly, MABP increased, while FVC decreased in all three CH groups (Figs 1 and 2). Considering the values attained in CH rats in the 5th minute of breathing 21% O2, relative to those recorded in N rats continuously breathing 21% O2, PaCO2 was higher and pHa lower in the 3 and 7CH rats than in N rats, reflecting the fact that VT remained higher in the CH rats than in the N rats, while RF in all CH rats fell to values similar to those recorded in N rats (Table 1, Fig. 1). On the other hand, the MABP and FVC values recorded in all CH rats in the 5th minute of breathing 21% O2 were comparable with those recorded in N rats breathing 21% O2 (Fig. 1).

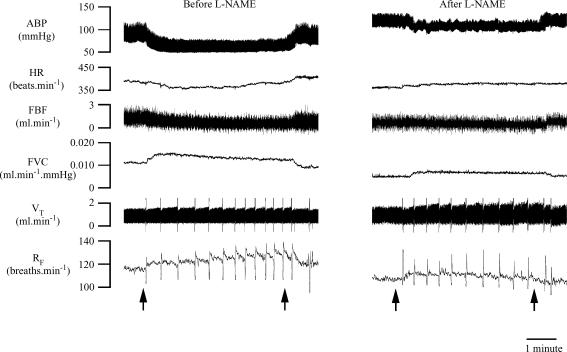

Figure 2. Original recordings of respiratory and cardiovascular responses evoked in 1CH rat by breathing 21% O2 for 5 min.

Arrows below indicate times at which inspirate was changed from 12% O2 to 21% O2 and back again. Abbreviations as in Fig. 1.

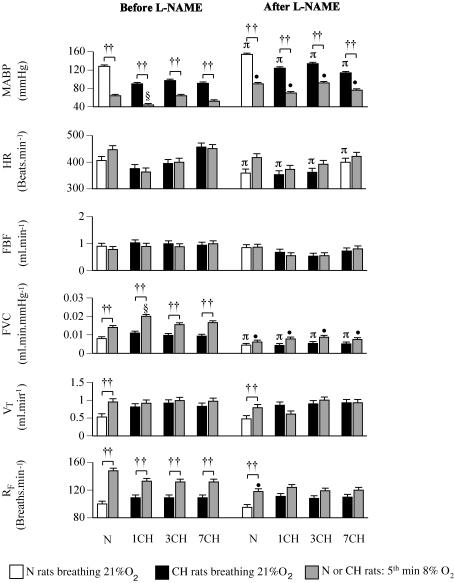

Group 2

Group 2 showed similar baseline blood gas and pH values for N rats breathing 21% O2 and CH rats breathing 12% O2 as described for Group 1 above (see Table 2). Similarly, baseline RF and VT were higher and MABP lower in 1, 3 and 7CH rats than in N rats, while FVC was higher in 1 and 3CH rats than in N rats (Fig. 3, P < 0.05 in each case). Switching the N rats from breathing 21% O2 to 8% O2 and the CH rats from breathing 12% O2 to 8% O2 for 5 min produced a similar pattern of change in N and all CH rats (Table 2, Figs 3 and 4). The PaO2 and PaCO2 fell and pHa increased, while RF increased in N and all CH rats; VT increased in the N rats, but not in CH rats (Figs 3 and 4). Comparing the N and CH rats, PaCO2 fell to lower levels and pHa increased to higher levels in all groups of CH rats than in N rats (Table 2). Concomitantly, MABP decreased and FVC increased in N and all CH rats, but MABP fell to a lower level and FVC to a higher level in 1CH rats than in N rats (Fig. 3). There were no significant changes in FBF or HR when values were compared in the end of the 5th minute of 8% O2 (Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Arterial blood gases and pHa recorded in N rats breathing air and in CH rats breathing 12% O2 and in both groups in the 5th minute of breathing 8% O2, before and after l-NAME (10 mg kg−1)

| PaO2 | PaCO2 | pHa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | ||

| N | 21% O2 | 88.63 ± 3.19 | 85.63 ± 3.00 | 44.32 ± 1.87 | 40.84 ± 3.03 | 7.35 ± 0.01 | 7.34 ± 0.02 |

| 8% O2 | 33.54 ± 1.14† | 31.71 ± 0.83† | 31.77 ± 1.61† | 31.79 ± 1.63† | 7.42 ± 0.02† | 7.41 ± 0.02† | |

| 1CH | 12% O2 | 41.28 ± 1.08* | 47.78 ± 1.08§ | 32.88 ± 1.42* | 31.77 ± 1.20 | 7.44 ± 0.01* | 7.37 ± 0.01§ |

| 8% O2 | 32.28 ± 0.79† | 32.80 ± 0.57† | 27.46 ± 1.62†‡ | 27.77 ± 1.20† | 7.46 ± 0.01†‡ | 7.45 ± 0.01† | |

| 3CH | 12% O2 | 40.85 ± 2.74* | 46.00 ± 2.00§ | 30.64 ± 2.74* | 32.03 ± 1.70 | 7.44 ± 0.03* | 7.36 ± 0.02§ |

| 8% O2 | 30.33 ± 4.10† | 31.33 ± 2.10† | 25.98 ± 1.51†‡ | 27.85 ± 1.51† | 7.48 ± 0.01†‡ | 7.44 ± 0.01† | |

| 7CH | 12% O2 | 40.57 ± 1.39* | 47.14 ± 1.83§ | 29.87 ± 1.70* | 29.35 ± 1.80 | 7.45 ± 0.01* | 7.37 ± 0.01§ |

| 8% O2 | 31.46 ± 0.54† | 33.14 ± 0.77† | 26.78 ± 2.47†‡ | 25.42 ± 1.99† | 7.47 ± 0.02†‡ | 7.46 ± 0.01† | |

All values are shown as mean ±s.e.m. Blood gas values are in mmHg.

P < 0.05 baseline values recorded in N rats breathing 21% O2versus CH rats breathing 12% O2.

P < 0.05: value recorded in N rats breathing 21% O2versus 8% O2 and between value recorded in CH rats breathing 12% O2versus 8% O2 before or after l-NAME.

P < 0.05: value recorded in N rats breathing 8% O2versus CH rats breathing 8% O2.

P < 0.05: baseline value recorded in N rats breathing 21% O2 before versus after l-NAME, or baseline value recorded in CH rats breathing 12% O2 before versus after l-NAME.

Figure 3. Respiratory and cardiovascular responses evoked by a 5-min period of acute hypoxia (breathing 8% O2) in N rats and 1, 3 and 7CH rats before and after l-NAME (left and right panels, respectively).

Groups of rats are indicated below the pairs of columns; abbreviations as in Fig. 1. In each case, left-hand column indicates value recorded under control conditions (breathing 21% O2 and 12% O2, N and CH rats, respectively), while right-hand column shows value recorded in the 5th minute of breathing 8% O2. Values are shown as mean ± s.e.m. ††P < 0.01, †P < 0.05: baseline versus 5th minute of 8% O2 in N or CH rats. §P < 0.05: 5th minute of breathing 8% O2 in CH versus N rats. πP < 0.05: baseline before versus after l-NAME in N or CH rats. •P < 0.05: value attained in 5th minute of 8% O2 before versus after l-NAME in N or CH rats. For simplicity, significance values for baselines in N rats breathing 21% O2 versus CH rats breathing 12% O2 are not shown.

Figure 4. Original recordings of respiratory and cardiovascular responses evoked in 1CH rat by breathing 8% O2 for 5 min before and after l-NAME.

Arrows below sets of traces indicate times at which inspirate was switched from 12% O2 to 8% O2 and back again. Abbreviations as in Fig. 1.

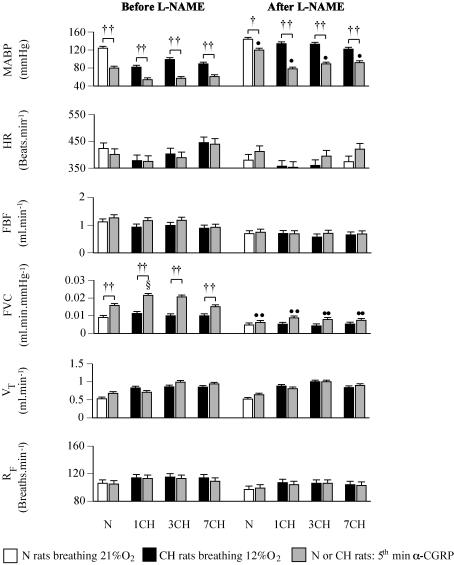

Infusion of α-CGRP had no effect on blood gases, pHa (data not shown), VT or RF in N or CH rats (Fig. 5). However, in both N and all CH rats, α-CGRP evoked a substantial increase in FVC and a concomitant fall in MABP, with no change in FBF or HR. The absolute level of FVC attained in the 5th minute of α-CGRP infusion was higher in 1CH rats than N rats and tended to be higher in 3CH than N rats (P = 0.09, see Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Respiratory and cardiovascular responses evoked by 5 min infusion of α-CGRP in N rats and 1, 3 and 7CH rats before and after l-NAME.

Groups of rats are indicated below pairs of columns; abbreviations as in Fig. 1. In each case, left-hand column indicates value recorded under control conditions (breathing 21% O2 and 12% O2 in N and CH rats, respectively), while right-hand column shows value recorded in 5th minute of α-CGRP infusion. Values are shown as mean ± s.e.m. ††P < 0.01, †P < 0.05: baseline value at 5th minute of α-CGRP infusion in N or CH rats. §P < 0.05: 5th minute of α-CGRP in CH versus N rats. ••P < 0.01, •P < 0.05: value attained in the 5th minute of α-CGRP infusion before versus after l-NAME in N or CH rats. For simplicity, effects of l-NAME on baselines are not shown.

Effects of l-NAME

The NOS inhibitor l-NAME induced an increase in PaO2 and a fall in pHa in 1, 3 and 7CH rats, but had no effect on blood gas or pHa values in N rats (Table 2). l-NAME had no effect on baseline VT, or RF in N or CH rats (Fig. 3). However, l-NAME produced an increase in baseline MABP and a decrease in FVC in N and CH rats, such that after l-NAME the baseline values of ABP and FVC were no longer different between CH and N rats (Fig. 3). Baseline HR also fell following l-NAME administration in N and 1–7CH rats (Fig. 3).

After l-NAME, 8% O2 produced similar PaO2, PaCO2 and pHa values in N and all CH rats (Table 2). Concomitantly, 8% O2 produced an increase in RF and VT in N rats, although RF reached a lower level than before l-NAME. However, there was no significant change in either variable in the CH rats (Figs 3 and 4). MABP fell in response to 8% O2 in N rats and all CH rats, but the levels of MABP attained were higher than during 8% O2 before l-NAME (Figs 3 and 4). However, any increases in FVC were not significant in N or CH rats, such that the FVC values attained in the 5th minute of 8% O2 were lower in N and all groups of CH rats than they were before l-NAME (Figs 3 and 4).

From the new baselines after l-NAME, α-CGRP again produced no changes in blood gases, pHa or ventilation in either N or CH rats. However, in both N and CH rats, the increase in FVC was attenuated such that the levels of FVC attained in the 5th minute of α-CGRP infusion were lower than before l-NAME (see Fig. 5). By contrast the fall in MABP evoked by α-CGRP persisted in both N and all CH rats, but MABP did not fall to such a low level after l-NAME in any group (see Fig. 5).

Discussion

The present study on N and 1–7CH rats, in which the acute experiments were performed under Saffan anaesthesia, confirmed that by the first day of chronic hypoxia, substantial changes in ventilation had already occurred that were maintained until the 7th day of chronic hypoxia (see Olson & Dempsey, 1978). The main new findings were that in 1CH rats breathing 12% O2, baseline HR was similar to that in N rats breathing 21% O2, but ABP was lower and FVC higher; in 7CH rats, FVC had returned to the level in N rats. Further, the levels to which FVC increased during acute hypoxia (8% O2) and infusion of α-CGRP, were enhanced in 1CH rats relative to N rats. However, after NOS inhibition with l-NAME, baseline ABP and FVC, and the increases in FVC evoked by acute hypoxia and by α-CGRP, were similar in all CH rats and N rats. Given the well-known interdependence of respiratory and cardiovascular responses, it is appropriate to give brief consideration to the ventilatory adaptations seen in the CH rats before discussing the cardiovascular changes.

In the present study, baseline VT and RF were similarly increased in 1, 3 and 7CH rats breathing 12% O2, relative to N rats breathing 21% O2, whereas Olson & Dempsey (1978) showed that in 1–4CH rats, the hyperventilation was mainly due to an increase in RF; thereafter and beyond the 7th day of hypoxia, both RF and VT progressively increased. This disparity may be attributed to the strain or state of the animals: we used Wistar rats under Saffan anaesthesia, while Olson & Dempsey (1978) used unanaesthetized Sprague-Dawley rats. However, the blood gas changes were similar in the two studies. The level of PaO2 attained in 1CH rats was maintained in 3 and 7CH rats and was accompanied by a hypocapnia that was constant in 1, 3 and 7CH; there was also a maintained alkalosis (see Olson & Dempsey, 1978).

The conclusion that ventilatory adaptation had already occurred even in 1CH rats is supported by the findings that N rats acutely breathing 12% O2 had higher RF and lower VT values than 1, 3 or 7CH rats breathing 12% O2, while when the CH rats acutely breathed 21% O2, RF fell, but VT remained high. Further, the higher VT values in CH than in N rats, both when breathing 12% O2 and when breathing 21% O2, meant that under both conditions, PaCO2 was lower and pHa higher in CH than in N rats. All of these findings are similar to those made by Olson & Dempsey (1978). Previous studies have indicated that these adaptive changes of chronic hypoxia reflect an increase in peripheral chemoreceptor sensitivity to O2 (Aaron & Powell, 1993; Dwinell & Powell, 1999) and a decrease in central sensitivity to CO2 (Dempsey & Forster, 1982).

Concomitant with these changes, Hct was increased in 3 and 7CH rats relative to N rats. The increase in Hct in 1–5CH rats has been ascribed to a decrease in plasma volume and release of erythrocytes and reticulocytes from the spleen, while in 7CH rats erythropoiesis probably plays a part (Ou et al. 1985, 1992; Kuwahira et al. 1999). As a consequence of the gradual increase in Hct, the arterial O2 content (CaO2) must have been increasing, despite the low PaO2: in a previous study, CaO2 in 7CH rats breathing 12% O2, was fully comparable with that of N rats breathing 21% O2 (Smith & Marshall, 1999).

Given the sustained hyperventilation of 1–7CH rats breathing 12% O2, the finding that baseline HR was similar to that of N rats breathing 21% O2 is particularly noteworthy. In N rats, whether under Saffan anaesthesia or unanaesthetized, the hyperventilation of acute hypoxia is associated with tachycardia arising from the central and reflex consequences of increased central respiratory drive, which may be followed by secondary bradycardia attributable to waning of the hyperventilation and to the local effects of hypoxia on the heart (Marshall & Metcalfe, 1990; Thomas & Marshall, 1994). Thus, it seems that the normal relationship between hyperventilation and HR is lost in 1–7CH rats. It is well known that resting HR and/or maximum HR is reduced in chronic hypoxia lasting 3–4 weeks in the rat and human subjects (see Kacimi et al. 1992; Thomas & Marshall, 1997). However, a decrease in cardiac β-receptor density, which is thought to underlie this phenomenon, was not present in 1, 3, 7 or 15CH rats, but was present in 3 week CH rats; adenyl cyclase activity was preserved throughout (Kacimi et al. 1992). It may be that in 1–7CH rats, the stimulatory influences on HR are overcome by the local depressive effects of hypoxia, which include the action of adenosine (see Thomas & Marshall, 1994; Walsh & Marshall, 2006).

The very fact that HR was similar in CH and N rats suggests that the reduced MABP in the CH rats reflected a fall in total peripheral resistance due to pronounced, tonic vasodilatation in skeletal muscle and other tissues: mesenteric vascular conductance was increased in unanaesthetized 2CH rats (Gonzales & Walker, 2002). Pulmonary stretch receptor stimulation and hypocapnia secondary to hyperventilation induce, at most, weak vasodilatation in the rat (Marshall, 1999). Thus, it can be argued that 1 and 3CH rats breathing 12% O2 showed a tonic muscle vasodilatation similar to the increase in FVC evoked in N rats by acute hypoxia, reflecting the predominance of the local dilator effects of hypoxia over vasoconstriction evoked by peripheral chemoreceptor stimulation (Marshall, 1999). In 7CH rats, it can be proposed this dilatation had waned because the increase in CaO2 and angiogenesis (see above and Smith & Marshall, 1999) had improved the O2 supply to skeletal muscle. However, it should be noted that because of the increase in the number of arteriolar resistance vessels in parallel, at least in 7CH rats, baseline FVC would have been expected to be higher in 7CH, than N rats (see Smith & Marshall, 1999). Thus, it seems likely there is also a counteracting increase in vasoconstrictor tone to muscle in the CH rats. An increase in muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) was reported in human subjects who had been at altitude for 4 weeks and in rats made chronically hypoxic for 4 weeks and studied under Saffan anaesthesia, that was only partly attributable to peripheral chemoreceptor stimulation and baroreceptor unloading (Hansen & Sander, 2003; Hudson & Marshall, 2005). The present results raise the possibility that this adaptive increase in MSNA begins in 1–7CH rats.

The finding that switching 1–7CH rats acutely from 12 to 21% O2 induced a decrease in FVC may suggest that even in 7CH rats, a tonic vasodilator influence of hypoxia was still present. Alternatively, as CaO2 has normalized in 7CH rats (see above), the switch to 21% O2 induced a vasoconstrictor response to hyperoxia, as proposed for 3–4 week CH rats (Thomas & Marshall, 1997). On the other hand, since acutely switching N rats to 12% O2 increased FVC to a higher level than in 3 and 7CH rats breathing 12% O2, it seems that some adaptation had occurred at least in the 3–7CH rats as would be consistent with an increase in MSNA (see above).

Acute hypoxia and α-CGRP

Switching N rats from breathing 21 to 8% O2 evoked the expected increase in RF, and VT (see Thomas & Marshall, 1994; Thomas et al. 1994). By contrast, switching 1, 3 and 7CH rats from 12 to 8% O2 had no significant effect on VT, but increased RF to levels similar to those reached in the N rats who experienced the larger change from 21 to 8% O2. Moreover, PaCO2 reached lower levels in all CH rats than in N rats. These findings are consistent with the conclusion that the 1–7CH rats had increased ventilatory sensitivity to O2 and decreased sensitivity to CO2 (see above).

In view of the lower PaCO2 and higher pHa in the CH rats, the haemoglobin (Hb) O2 dissociation curve is likely to be have been further leftward-shifted in CH than in N rats, resulting in a higher HbO2 saturation at a given PaO2. This, together with the higher Hct in the 3 and 7CH rats than N rats, indicates that the decreases in PaO2 and CaO2 induced by switching CH rats from 12 to 8% O2 were much smaller than those induced by switching N rats from 21 to 8% O2, and that CaO2 did not fall to such a low level in CH, as in N rats. It is therefore particularly remarkable that, when breathing 8% O2, MABP decreased and FVC increased to similar levels in 3 and 7CH rats as in N rats, and that in 1CH rats, MABP reached a lower level and FVC a substantially higher level than in N rats. These results suggest that responsiveness to the local muscle vasodilator influences of acute hypoxia is increased in 1CH rats. It is probably increased in 3 and 7CH rats as well, for the increase in the number of arteriolar resistance vessels in parallel that occurs in skeletal muscle, leads to an increase in maximal, or structural FVC, at least in 7CH rats (Smith & Marshall, 1999). Thus, even if the same increase in the diameter of individual arterioles had been evoked in 7CH and N rats by the switch to 8% O2, this would have increased FVC to a lower level in 7CH than in N rats, not to the same level as actually occurred. We have already shown that the switch from 12 to 8% O2 evoked comparable increases in the diameter of skeletal muscle arterioles of 3–4 week CH rats as in N rats switched from 21 to 8% O2 (see Mian & Marshall, 1996). The present results indicate that this accentuated dilator responsiveness begins in 1–7CH rats.

Similar comments can be made on the responses evoked by α-CGRP. Infusion of α-CGRP evoked the expected increase in FVC and fall in ABP in N rats (Gardiner et al. 1991). The finding that α-CGRP increased FVC to a higher level in 1CH than N rats cannot have been complicated by an increase in the number of arteriolar branches. Further, α-CGRP evoked increases in FVC in 3 and 7CH rats that were at least as large as in N rats. Thus, we propose that dilator responsiveness to α-CGRP was accentuated in 3 and 7CH, as well as in 1CH rats.

Role of NO

Ventilation

In accord with previous studies (see Barros & Branco, 1998; Gautier & Murariu, 1999), l-NAME had no effect on baseline VT or RF in N rats breathing 21% O2, but reduced the increase in RF evoked by acute hypoxia (8% O2). Thus, NO apparently makes no contribution to normoxic ventilation in the rat, but facilitates the ventilatory response to acute hypoxia. Since NO is recognized as an inhibitory modulator of carotid body afferent activity (Prabhakar, 1999), it is likely the facilitatory effect of NO occurred within the central nervous system. l-NAME given systemically at 10 mg kg−1 can penetrate the blood–brain barrier at pharmacologically active concentrations (Iadecola et al. 1994). Moreover, NO generated by neuronal NOS has been reported to facilitate the ventilatory response to acute hypoxia by modulating transmission within the nucleus of the tractus solitarius (Ogawa et al. 1995).

The finding that l-NAME had no effect on baseline RF in 1–7CH rats breathing 12% O2 indicates that NO did not contribute to their tonically raised RF. Nevertheless, as l-NAME substantially dampened the increases in RF evoked by 8% O2 in all CH rats such that they no longer reached significance, the facilitatory influence of NO on the ventilatory response to acute hypoxia may be even greater in 1–7CH rats than in N rats.

Cardiovascular baselines

In N rats, l-NAME caused a marked increase in baseline ABP and fall in baseline FVC in N rats, consistent with previous reports that tonically generated NO exerts a major dilator influence on skeletal muscle and other vascular beds under normoxic conditions (e.g. Gardiner et al. 1991; Skinner & Marshall, 1996). The concomitant decrease in baseline HR may be attributed to a baroreceptor reflex response to the increase in ABP associated with removal of the tonic inhibitory influence of NO on cardiac vagal activity (Zanzinger, 1999).

Our new finding that l-NAME increased baseline ABP in 1, 3 and 7CH rats breathing 12% O2, and reduced baseline FVC such that ABP and FVC attained levels comparable to those seen after l-NAME in N rats breathing 21% O2, strongly suggests that the reduced baseline ABP and increased FVC that characterized the CH rats were attributable to a stronger tonic dilator influence of NO, at least in skeletal muscle. Since baseline HR fell to similar levels after l-NAME in the CH as in the N rats, it seems that the inhibitory influence of NO on cardiac vagal tone (see above) was similar in 1–7CH and N rats.

At this stage, it should be noted that l-NAME also increased baseline PaO2 and decreased baseline pHa in 1, 3 and 7CH rats, but not in N rats. These changes cannot be accounted for by changes in baseline ventilation (see above). Rather, we suggest they are attributable to a decrease in O2 consumption  in skeletal muscle and other tissues, secondary to the tonic vasoconstriction caused by l-NAME. It is known that NO exerts an inhibitory influence on

in skeletal muscle and other tissues, secondary to the tonic vasoconstriction caused by l-NAME. It is known that NO exerts an inhibitory influence on  by inhibiting mitochondrial respiration (Shen et al. 1997). Thus, removal of a tonic inhibitory influence on mitochondrial respiration might have been expected to increase

by inhibiting mitochondrial respiration (Shen et al. 1997). Thus, removal of a tonic inhibitory influence on mitochondrial respiration might have been expected to increase  as shown in dog skeletal muscle (King et al. 1994). However, in a previous study on N rats, we could only demonstrate an increase in muscle

as shown in dog skeletal muscle (King et al. 1994). However, in a previous study on N rats, we could only demonstrate an increase in muscle  after l-NAME, when baseline FVC was restored by infusion of the vasodilator iloprost (Edmunds & Marshall, 2001). In the absence of such a dilator infusion, the tonic vasoconstrictor influence of NOS inhibition decreased the O2 delivery (DO2) to skeletal muscle so much that further reductions in DO2 produced by breathing graded hypoxic mixtures caused

after l-NAME, when baseline FVC was restored by infusion of the vasodilator iloprost (Edmunds & Marshall, 2001). In the absence of such a dilator infusion, the tonic vasoconstrictor influence of NOS inhibition decreased the O2 delivery (DO2) to skeletal muscle so much that further reductions in DO2 produced by breathing graded hypoxic mixtures caused  to decrease in a linear fashion (Edmunds & Marshall, 2001). It should be noted that when there was no NOS blockade, muscle

to decrease in a linear fashion (Edmunds & Marshall, 2001). It should be noted that when there was no NOS blockade, muscle  was well maintained during graded hypoxia, by vasodilatation and increased O2 extraction, until the level of hypoxia was very severe; then

was well maintained during graded hypoxia, by vasodilatation and increased O2 extraction, until the level of hypoxia was very severe; then  fell progressively with DO2 (Edmunds & Marshall, 2001). Thus, we now propose that in 1, 3 and 7CH rats, the DO2 to skeletal muscle was already so compromised by the reduced PaO2, that the tonic muscle vasoconstriction caused by l-NAME compromised oxidative metabolism such that PaO2 increased and anaerobic metabolism led to a fall in pHa. In future studies, this could be tested by monitoring plasma lactate. If our proposal is correct, then the present results suggest that in 1–7CH rats, the dilator influence of tonically released NO plays an important role in maintaining whole body

fell progressively with DO2 (Edmunds & Marshall, 2001). Thus, we now propose that in 1, 3 and 7CH rats, the DO2 to skeletal muscle was already so compromised by the reduced PaO2, that the tonic muscle vasoconstriction caused by l-NAME compromised oxidative metabolism such that PaO2 increased and anaerobic metabolism led to a fall in pHa. In future studies, this could be tested by monitoring plasma lactate. If our proposal is correct, then the present results suggest that in 1–7CH rats, the dilator influence of tonically released NO plays an important role in maintaining whole body  .

.

Acute hypoxia and α-CGRP

That l-NAME virtually abolished the fall in ABP and increase in FVC evoked in N rats by acute hypoxia (8% O2) is consistent with the conclusion that muscle vasodilatation evoked by acute hypoxia is NO dependent and partly mediated by the action of adenosine on NO synthesis (e.g. Skinner & Marshall, 1996; Edmunds et al. 2003; Ray & Marshall, 2005). The new finding that l-NAME attenuated the decrease in ABP and increase in FVC evoked by 8% O2 in CH rats indicates that their accentuated muscle vasodilator responses to acute hypoxia, relative to N rats (see above), were due to an accentuated influence of NO.

Similarly, the increase in FVC evoked by α-CGRP was substantially reduced by l-NAME in N rats, confirming the report of Gardiner et al. (1991) that the muscle dilator response to CGRP is largely NO dependent and partly mediated by NO via cGMP, as well as by cAMP (Kubota et al. 1985; Wang et al. 1991; Fiscus et al. 1994). That l-NAME attenuated the increases in FVC evoked by α-CGRP in all CH rats, so they became fully comparable to that induced in N rats after l-NAME, strongly suggests the accentuated muscle dilator responses to α-CGRP that occurred in CH rats before l-NAME were attributable to a greater influence of NO.

Taken together, these findings raise the question of whether the accentuated tonic, and agonist-stimulated, influences of NO seen in early chronic hypoxia reflect an increase in the expression of NOS in the vasculature of skeletal muscle and other tissues. Hypoxia (PO2, 20 mmHg) for 1–2 days decreased endothelial NOS (eNOS) RNA and protein in endothelial cells of human umbilical and saphenous vein, and bovine pulmonary artery and aorta (McQuillan et al. 1994; Liao et al. 1995; Phelan & Faller, 1996). By contrast, a PO2 of 20 mmHg for 1 day increased eNOS RNA and protein in bovine aortic endothelial cells, but caused a parallel decrease in eNOS activity (Arnet et al. 1996). On the other hand, chronic systemic hypoxia increased mRNA and protein for eNOS and inducible (i)NOS in pulmonary arterial vessels of 1–7CH rats, concomitant with pulmonary vascular remodelling (Xue & Johns, 1996; Le Cras et al. 1996; Toporsian et al. 2000). By contrast, in the thoracic aorta, eNOS RNA and protein was decreased in 1CH rats and this persisted in 7CH rats (Toporsian et al. 2000).

Thus, there is no consensus on the effects of hypoxia per se on eNOS in endothelial cells in culture, while the effects of chronic systemic hypoxia seem to be directionally different for eNOS in pulmonary circulation and thoracic aorta. There has been no study of the effects of early chronic hypoxia on the expression or activity of eNOS or iNOS in the resistance vessels of skeletal muscle. However, we recently reported that neither eNOS mRNA or protein, nor iNOS protein is increased in homogenates of skeletal muscle of 1–14CH rats (Glen et al. 2005).

Even if eNOS or iNOS expression is not increased in skeletal muscle arterioles in early chronic hypoxia, the greater tonic vasodilator influence of NO we have demonstrated in 1–7CH rats may be attributed to the continuing stimulatory actions on eNOS of the local and hormonal substances whose concentrations are increased by acute hypoxia, such as adenosine (Thomas & Marshall, 1994; Bryan & Marshall, 1999a) and by an increase in shear stress when Hct begins to increase (see Pohl & de Wit, 1999). In the presence of tonic activation of eNOS, the stimulatory effects of substances released by a further acute hypoxic stimulus, such as adenosine and adrenaline (Mian & Marshall, 1991; Edmunds et al. 2003) and by exogenous factors such as α-CGRP, would be expected to be facilitated just as we have described, in view of the synergistic interactions of cAMP and cGMP (de Wit et al. 1994).

In summary, the present study on 1–7CH rats demonstrated that in the first few days of chronic hypoxia, the resting hyperventilation has no significant effect on HR or muscle vasculature. Rather, HR is unchanged while there is substantial tonic muscle vasodilation and a fall in ABP indicating predominance of the local dilator influences of tissue hypoxia over reflex effects of peripheral chemoreceptor stimulation. Our evidence suggests that this tonic dilator influence is largely mediated by increased synthesis and release of NO and that further muscle vasodilatation evoked by an acute hypoxic challenge or by an NO-dependent dilator is also accentuated. By the 7th day of hypoxia, ABP is largely restored and the tonic dilator influence of NO on muscle vasculature is greatly attenuated. We propose this arises because the increase in Hct and vascular remodelling in skeletal muscle restores the O2 supply to normal levels. Nevertheless, our results indicate that at the 7th day of chronic hypoxia, muscle vasculature still shows accentuated dilator responses to acute hypoxia and NO-dependent dilators as we have reported after 3–4 weeks of chronic hypoxia (see Mian & Marshall, 1996; Smith & Marshall, 1999). Whether the tonic drive for NO synthesis in early chronic hypoxia is partly mediated by adenosine, which induces NO-dependent muscle vasodilatation in acute hypoxia (e.g. Ray & Marshall, 2005), and whether NO is synthesized by iNOS as well as eNOS, are important issues addressed in our companion paper (Walsh & Marshall, 2006).

References

- Aaron EA, Powell FL. Effect of chronic hypoxia on hypoxic ventilatory response in awake rats. J Appl Physiol. 1993;74:1635–1640. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.4.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnet UA, McMillan A, Dinerman JL, Ballermann B, Lowenstein CJ. Regulation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase during hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15069–15073. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.25.15069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros RC, Branco LG. Effect of nitric oxide synthase inhibition on hypercapnia-induced hypothermia and hyperventilation. J Appl Physiol. 1998;85:967–972. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.3.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett IS, Marshall JM. Effects of chronic systemic hypoxia on contraction evoked by noradrenaline in the rat iliac artery. Exp Physiol. 2003;88:497–507. doi: 10.1113/eph8802564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blitzer ML, Lee SD, Creager MA. Endothelium-derived nitric oxide mediates hypoxic dilation of resistance vessels in humans. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H1182–H1185. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.3.H1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan PT, Marshall JM. Cellular mechanisms by which adenosine induces vasodilatation in rat skeletal muscle, significance for systemic hypoxia. J Physiol. 1999a;514:163–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.163af.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan PT, Marshall JM. Adenosine receptor subtypes and vasodilatation in rat skeletal muscle during systemic hypoxia: a role for A1 receptors. J Physiol. 1999b;514:151–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.151af.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coney AM, Bishay M, Marshall J. Influence of endogenous nitric oxide on sympathetic vasoconstriction in normoxia, acute and chronic systemic hypoxia in the rat. J Physiol. 2004;555:793–804. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.058156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey JA, Forster HV. Mediation of ventilatory adaptations. Physiol Rev. 1982;62:262–346. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1982.62.1.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveci D, Marshall JM, Egginton S. Relationship between capillary angiogenesis, fiber type, and fiber size in chronic systemic hypoxia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H241–H252. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.1.H241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit C, von Bismarck P, Pohl U. Synergistic action of vasodilators that increase cGMP and cAMP in hamster cremaster microcirculation. Cardiovasc Res. 1994;28:1513–1518. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.10.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle MP, Walker BR. Attenuation of systemic vasoreactivity in chronically hypoxic rats. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:R1114–R1122. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.260.6.R1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwinell MR, Powell FL. Chronic hypoxia enhances the phrenic nerve response to arterial chemoreceptor stimulation in anaesthetised rats. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:817–823. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.2.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmunds NJ, Marshall JM. Vasodilatation, oxygen delivery and oxygen consumption in rat hindlimb during systemic hypoxia, roles of nitric oxide. J Physiol. 2001;532:251–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0251g.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmunds NJ, Moncada S, Marshall JM. Does nitric oxide allow endothelial cells to sense hypoxia and mediate hypoxic vasodilatation?In vivo and in vitro studies. J Physiol. 2003;546:521–527. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.023663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiscus RR, Hao H, Wang X, Arden WA, Diana JN. Nitroglycerin (exogenous nitric oxide) substitutes for endothelium-derived nitric oxide in potentiating vasorelaxations and cyclic AMP elevations induced by calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) in rat aorta. Neuropeptides. 1994;26:133–144. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(94)90104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner SM, Compton AM, Kemp PA, Bennett T, Foulkes R, Hughes B. Haemodynamic effects of human alpha-calcitonin gene-related peptide following administration of endothelin-1 or NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester in conscious rats. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;103:1256–1262. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12333.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier H, Murariu C. Role of nitric oxide in hypoxic hypometabolism in rats. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:104–110. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glen KE, Stroka DM, Marshall JM. Changes in iNOS, VEGF and eNOS protein expression induced by chronic hypoxia in skeletal muscle in vivo. XXXV International Congress of Physiological Sciences. Exp Biol. 2005;A927:136.2. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales RJ, Walker BR. Role of CO in attenuated vasoconstrictor reactivity of mesenteric resistance arteries after chronic hypoxia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H30–H37. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2002.282.1.H30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Alonso J, Richardson RS, Saltin B. Exercising skeletal muscle blood flow in humans responds to reduction in arterial oxyhaemoglobin, but not to altered free oxygen. J Physiol. 2001;530:331–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0331l.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen J, Sander M. Sympathetic neural overactivity in healthy humans after prolonged exposure to hypobaric hypoxia. J Physiol. 2003;546:921–929. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.031765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heistad DD, Wheeler RC. Effect of acute hypoxia on vascular responsiveness in man. I. Responsiveness to lower body negative pressure and ice on the forehead. II. Responses to norepinephrine and angiotensin. III. Effect of hypoxia and hypocapnia. J Clin Invest. 1970;49:1252–1265. doi: 10.1172/JCI106338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson S, Marshall JM. Influence of chronic systemic hypoxia on the sympathetic nerve supply to skeletal muscle vasculature. XXXV International Congress of Physiological Sciences. Exp Biol. 2005;A727:390.4. [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C, Zhang F, Xu X. SIN-1 reverses attenuation of hypercapnic cerebrovasodilation by nitric oxide synthase inhibitors. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:R228–R235. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.267.1.R228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kacimi R, Richalet J-P, Corsin A, Abousahl I, Crozatier B. Hypoxia-induced down regulation of β-adrenergic receptors in rat heart. J Appl Physiol. 1992;73:1377–1382. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.4.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King CE, Melinyshyn MJ, Mewburn JD, Curtis SE, Winn MJ, Cain SM, Chapler CK. Canine hind limb blood flow and O2 uptake after inhibition of EDRF/NO synthesis. J Appl Physiol. 1994;76:1166–1171. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.3.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota M, Moseley JM, Butera L, Dusting GJ, MacDonald PS, Martin TJ. Calcitonin gene-related peptide stimulates cyclic AMP formation in rat aortic smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1985;132:88–94. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(85)90992-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwahira I, Heisler N, Piiper J, Gonzalez NC. Effect of chronic hypoxia on hemodynamics, organ blood-flow and O2 supply in rats. Respir Physiol. 1993;92:227–238. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(93)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwahira I, Kamiya U, Iwamoto T, Moue Y, Urano T, Ohta Y, Gonzalez NC. Splenic contraction-induced reversible increase in haemoglobin concentration in intermittent hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 1999;86:181–187. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Cras TD, Xue C, Rengasamy A, Johns RA. Chronic hypoxia upregulates endothelial and inducible NO synthase gene and protein expression in rat lung. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:L164–L170. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.270.1.L164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao JK, Zulueta JJ, Yu FS, Peng HB, Cote CG, Hassoun PM. Regulation of bovine endothelial constitutive nitric oxide synthase by oxygen. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2661–2666. doi: 10.1172/JCI118332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JM. The Joan Mott Prize Lecture. The integrated response to hypoxia: from circulation to cells. Exp Physiol. 1999;84:449–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JM. Roles of adenosine and nitric oxide in skeletal muscle in acute and chronic hypoxia. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2001;502:349–363. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-3401-0_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JM, Metcalfe JD. Effects of systemic hypoxia on the distribution of cardiac output in the rat. J Physiol. 1990;427:335–353. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuillan LP, Leung GK, Marsden PA, Kostyk SK, Kourembanas S. Hypoxia inhibits expression of eNOS via transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:H1921–H1927. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.5.H1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mian R, Marshall JM. The roles of catecholamines in responses evoked in arterioles and venules of rat skeletal muscle by systemic hypoxia. J Physiol. 1991;436:499–510. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mian R, Marshall JM. The behaviour of muscle microcirculation in chronically hypoxic rats, the role of adenosine. J Physiol. 1996;491:489–498. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa H, Mizusawa A, Kikuchi Y, Hida W, Miki H, Shirato K. Nitric oxide as a retrograde messenger in the nucleus tractus solitarii of rats during hypoxia. J Physiol. 1995;486:495–504. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson EB, Jr, Dempsey JA. Rat as a model for human-like ventilatory adaptation to chronic hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 1978;44:763–769. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1978.44.5.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou IC, Cai YN, Tenny SM. Responses of blood volume and red cell mass in two strains of rats acclimatised to high altitude. Respir Physiol. 1985;62:85–94. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(85)90052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou IC, Chen J, Fiore E, Leiter JC, Brinck-Johnsen T, Birchard GF, Clemons G, Smith RP. Ventilatory and haematopoietic responses to chronic hypoxia in two rat strains. J Appl Physiol. 1992;72:2354–2363. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.6.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan MW, Faller DV. Hypoxia decreases constitutive nitric oxide synthase transcript and protein in cultured endothelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 1996;167:469–476. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199606)167:3<469::AID-JCP11>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohl U, de Wit C. A unique role of NO in the control of blood flow. News Physiol Sci. 1999;14:74–80. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.1999.14.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar NR. NO and CO as second messengers in oxygen sensing in the carotid body. Respir Physiol. 1999;115:161–168. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(99)00019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price RJ, Skalak TC. Arteriolar remodelling in skeletal muscle of rats exposed to chronic hypoxia. J Vasc Res. 1998;35:238–244. doi: 10.1159/000025589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray CJ, Abbas MR, Coney AM, Marshall JM. Interactions of adenosine, prostaglandins and nitric oxide in hypoxia-induced vasodilatation: in vivo and in vitro studies. J Physiol. 2002;544:195–209. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.023440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray CJ, Marshall JM. Measurement of nitric oxide release evoked by systemic hypoxia and adenosine from rat skeletal muscle in vivo. J Physiol. 2005;568:967–978. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.094854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowell LB, Johnson DG, Chase PB, Comess KA, Seals DR. Hypoxemia raises muscle sympathetic activity but not norepinephrine in resting humans. J Appl Physiol. 1989;66:1736–1743. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.66.4.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W, Wolin MS, Hintze TH. Defective endogenous nitric oxide-mediated modulation of cellular respiration in canine skeletal muscle after the development of heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1997;16:1026–1034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner MR, Marshall JM. Studies on the roles of ATP, adenosine and nitric oxide in mediating muscle vasodilation induced in the rat by acute systemic hypoxia. J Physiol. 1996;495:553–560. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K, Marshall JM. Physiological adjustments and arteriolar remodelling within skeletal muscle during acclimation to chronic hypoxia in the rat. J Physiol. 1999;521:261–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas T, Elnazir BK, Marshall JM. Differentiation of the peripherally mediated from the centrally mediated influences of adenosine in the rat during systemic hypoxia. Exp Physiol. 1994;79:809–822. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1994.sp003809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas T, Marshall JM. Interdependence of respiratory and cardiovascular changes induced by systemic hypoxia in the rat, the roles of adenosine. J Physiol. 1994;480:627–636. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas T, Marshall JM. The roles of adenosine in regulating the respiratory and cardiovascular systems in chronically hypoxic, adult rats. J Physiol. 1997;501:439–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.439bn.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toporsian M, Govindaraju K, Nagi M, Eidelman D, Thibault G, Ward ME. Downregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in rat aorta after prolonged hypoxia in vivo. Circ Res. 2000;86:671–675. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.6.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh MP, Marshall JM. The role of adenosine in the early respiratory and cardiovascular changes evoked by chronic hypoxia in the rat. J Physiol. 2006;575:277–289. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.108779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Han C, Fiscus RR. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) causes endothelium-dependent cyclic AMP, cyclic GMP and vasorelaxant responses in rat abdominal aorta. Neuropeptides. 1991;20:115–124. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(91)90061-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue C, Johns RA. Upregulation of nitric oxide synthase correlates temporally with onset of remodelling in the hypoxic rat. Hypertension. 1996;28:743–753. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.28.5.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanzinger J. Role of nitric oxide in the neural control of cardiovascular function. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;43:639–649. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]