Abstract

Voltage-gated Kv7 (KCNQ) channels underlie important K+ currents in many different types of cells, including the neuronal M current, which is thought to be modulated by muscarinic stimulation via depletion of membrane phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2). We studied the role of modulation by angiotensin II (angioII) of M current in controlling discharge properties of superior cervical ganglion (SCG) sympathetic neurons and the mechanism of action of angioII on cloned Kv7 channels in a heterologous expression system. In SCG neurons, which endogenously express angioII AT1 receptors, application of angioII for 2 min produced an increase in neuronal excitability and a decrease in spike-frequency adaptation that partially returned to control values after 10 min of angioII exposure. The increase in excitability could be simulated in a computational model by varying only the amount of M current. Using Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells expressing cloned Kv7.2 + 7.3 heteromultimers and AT1 receptors studied under perforated patch clamp, angioII induced a strong suppression of the Kv7.2/7.3 current that returned to near baseline within 10 min of stimulation. The suppression was blocked by the phospholipase C inhibitor edelfosine. Under whole-cell clamp, angioII moderately suppressed the Kv7.2/7.3 current whether or not intracellular Ca2+ was clamped or Ca2+ stores depleted. Co-expression of PI(4)5-kinase in these cells sharply reduced angioII inhibition, but did not augment current amplitudes, whereas co-expression of a PIP2 5′-phosphatase sharply reduced current amplitudes, and also blunted the inhibition. The rebound of the current seen in perforated-patch recordings was blocked by the PI4-kinase inhibitor, wortmannin (50 μm), suggesting that PIP2 re-synthesis is required for current recovery. High-performance liquid chromatographic analysis of anionic phospholipids in CHO cells stably expressing AT1 receptors revealed that PIP2 and phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate levels are to be strongly depleted after 2 min of stimulation with angioII, with a partial rebound after 10 min. The results of this study establish how angioII modulates M channels, which in turn affects the integrative properties of SCG neurons.

The M current of neurons is a voltage-gated, non-inactivating K+ current that plays a dominant role in regulating neuronal excitability (Marrion, 1997; Gu et al. 2005; Peters et al. 2005). It is named because of its suppression by muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (mAChR) stimulation in sympathetic neurons (Brown & Adams, 1980; Constanti & Brown, 1981). This action is via Gαq/11-coupled M1 receptors and activation of phospholipase C (PLC) (Haley et al. 1998). In the same neurons, three other types of Gq/11-coupled receptors also suppress the M current, angiotensin II (angioII) AT1 (Constanti & Brown, 1981; Shapiro et al. 1994), bradykinin B2 (Jones et al. 1995) and purinergic P2Y (Akasu et al. 1983; Tokimasa & Akasu, 1990; Filippov et al. 1994) receptors, with several different mechanisms serving to mediate these receptor actions (Delmas & Brown, 2005). Since the identification of the KCNQ(Kv7) gene products as underlying M-type currents, Kv7 channels have been found throughout the peripheral and central nervous system, composed of homo- and heteromeric assembly of the Kv7.2, 7.3 and 7.5 members of this channel family (Wang et al. 1998; Lerche et al. 2000; Cooper et al. 2001; Roche et al. 2002).

In addition to its crucial hormonal action to regulate cardiovascular and renal functions, angioII also acts in the central and peripheral nervous systems as a neuromodulator. Recently, angioII has been shown to augment short-term and long-term synaptic potentiation in sympathetic ganglia cells (Aileru et al. 2004), and a role for angioII in alterations of ganglionic function in hypertensive animal models has been suggested (Yarowsky & Weinreich, 1985; Magee & Schofield, 1994). AngioII was identified early on as a potent modulator of the M current (Constanti & Brown, 1981), and M current suppression in sympathetic neurons has been shown to be mediated by AT1 receptors, Gq/11 and an intracellular second messenger (Shapiro et al. 1994; Haley et al. 1998). The lack of Ca2+i signals provoked by angioII-induced stimulation in those cells has suggested that angioII and muscarinic modulation of M currents are mediated by identical signalling mechanisms (Shapiro et al. 1994).

Growing literature suggests that phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) controls the activity of Kv7 channels, much as for a number of other ion channels and transporters (Suh & Hille, 2005). It is now generally agreed that M channels are sensitive to the abundance of membrane PIP2, and that activation of PLC, and subsequent PIP2 hydrolysis, can sufficiently deplete the membrane of PIP2 to cause the observed depression of M currents by muscarinic stimulation (Suh & Hille, 2002; Ford et al. 2003; Zhang et al. 2003; Suh et al. 2004; Li et al. 2005). However, the primary signal for M current suppression by B2 or P2Y receptor stimulation seems to be not depletion of PIP2, but rather increases in [Ca2+]i (Cruzblanca et al. 1998; Bofill-Cardona et al. 2000; Delmas et al. 2002), probably in concert with calmodulin (Gamper & Shapiro, 2003; Gamper et al. 2005a).

Given the clear role of M-type channels in the control of neuronal excitability, we probed the effects of modulation of M current by angioII on the firing properties of superior cervical ganglion (SCG) neurons. We found that suppression by angioII of M current produces a robust increase in neuronal excitability through a change in resting potential and spike threshold, and a marked reduction in spike frequency adaptation. To investigate the molecular mechanism of modulation of M current by angioII, Kv7.2/7.3 channels and AT1 receptors were heterologously expressed in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells and in this system we investigated the involvement of PIP2. Additionally, we used analytical biochemistry to determine whether such stimulation of the cloned receptors can substantially deplete mammalian cells of PIP2. We conclude that changes in PIP2 levels are involved in the modulation by angioII of Kv7 channels, and this underlies its regulation of neuronal excitability.

Methods

cDNA constructs

Plasmids encoding human Kv7.2 and rat Kv7.3 (GenBank accession numbers AF110020 and AF091247, respectively) were kindly given to us by David McKinnon (State University of New York, Stony Brook, NY, USA). Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 were subcloned into pcDNA3 (Invitrogen) as previously described (Shapiro et al. 2000). The EGFP-Lyn-PH-PP and EGFP-Akt-PH constructs were kind gifts of Tobias Meyer (Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Type 1α PI(4)P5-kinase was kindly given to us by Lutz Pott (Ruhr-University, Bochum, Germany). The CHO cell line stably expressing angiotensin AT1 receptors was kindly given to us by Catherine Monnot (Collège de France, Paris). The human AT1 receptor clone was purchased from the Guthrie Foundation (Sayre, PA, USA).

Cell culture and transfections

CHO cells were used for electrophysiological analysis as recently described (Gamper et al. 2005b). Cells were grown in 100-mm tissue culture dishes (Falcon; Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA, USA) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 0.1% penicillin-streptomycin in a humidified incubator at 37°C (5% CO2) and passaged every 3–4 days. Cells were discarded after ∼30 passages. For transfection, cells were plated onto poly-l-lysine-coated coverslip chips and transfected 24 h later with Polyfect reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For electrophysiological experiments, cells were used 48–96 h after transfection. As a marker for successfully transfected cells, cDNA encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP) was cotransfected together with the cDNA of the genes of interest. We found that > 95% of green-fluorescing cells expressed Kv7 currents in control experiments.

Perforated-patch current clamp

SCG neurons were cultured from juvenile rats as previously described (Bernheim et al. 1991; Gamper et al. 2003). Rats were anaesthetized by inhalation of halothane, until completely non-responsive, and decapitated. The experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines laid down by the University of Texas Health Science Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Neurons were studied under current clamp with an EPC-9 amplifier and PULSE software using the perforated-patch recording technique (Rae et al. 1991). A stock solution of 50 mg amphotericin-B/1 ml DMSO was prepared and stored in the dark. For recordings, 50–75 μ l of this stock was dissolved in 1 ml of pipette solution using an ultrasonicator. Electrical recordings were made once the access resistance from the pipette to the cell interior fell to < 15 MΩ, usually 1–5 min after achieving a pipette-to-membrane seal resistance of > 2–3 GΩ. Action potentials were evoked and recorded with an EPC-9 amplifier (HEKA Electronic), at a sampling frequency of 2.5 kHz.

Whole-cell and perforated-patch voltage clamp

Whole-cell patch-clamp experiments were performed as previously described (Gamper et al. 2003). To evaluate the amplitude of macroscopic Kv7.2/7.3 currents, CHO cells were held at 0 mV, and 800-ms hyperpolarizing steps to −60 mV were applied, followed by 1-s pulses back to 0 mV. The amplitude of the current was usually defined as the difference between the holding current at 0 mV and the current at the beginning (after any capacity current had subsided) of the 1-s pulse back to 0 mV. In some cells, a more precise measurement was the XE991- or linopirdine-sensitive current at the holding potential of 0 mV. CHO cells have negligible endogenous macroscopic K+ currents under our experimental conditions, and 50 μm XE991 or linopirdine completely blocks the K+ current in Kv7-transfected CHO cells, but has no effect on currents in non-transfected cells (Gamper et al. 2005b). All results are reported as means ±s.e.m.

Computer modelling

Simulations were performed using NEURON v5.7 (Hines & Carnevale, 2001) on a Macintosh G4 computer. The passive properties of a single-compartment model (50 μm diameter) were chosen to reflect the input resistance and charging time constant of SCG neurons to negative current steps (specific membrane resistivity, 50 000 Ω cm2; specific capacitance, 1 μF cm−2). Four voltage-gated and two Ca2+-dependent conductances (available for download through ModelDB at http://senselab.med.yale.edu) were inserted into the model as indicated. A fast voltage-gated Na+ conductance (nahh.mod) (Traub et al. 1991) was inserted with a density of 4 mS cm−2. Threshold was adjusted by modifying the model file, shifting the forward and backward activation rate constants by +20 and +10 mV, respectively. Spike repolarization was achieved with a delayed rectifier K+ conductance (kdr.mod) (Migliore et al. 1995) at a density of 0.8 mS cm−2 (EK, −80 mV). A high-threshold voltage-gated Ca2+ conductance (cal.mod) (Migliore et al. 1995) at a density of 1 mS cm−2 was inserted with the equilibrium potential for Ca2+ determined by the Goldman–Hodgkin–Katz equation. Intracellular calcium dynamics were modelled as a single-shell process (cadifus.mod). In our final model, we also employed a BK-like Ca2+-dependent conductance (BK; cagk.mod) at a density of 0.1 mS cm−2. Finally, the M current model (borgkm.mod) (Borg-Graham, 1991; Migliore et al. 1995), with a half-maximal activation of −40 mV, was added with a maximum conductance density of 0.01 mS cm−2. It was assumed that the M current was active and contributed to the resting potential of the cell. Therefore, the equilibrium potential of the leak conductance was determined with no M current, giving a resting potential (Vrest) of −50 mV. Vrest was −62 mV when gK,M was maximum.

Phosphoinositide analysis

CHO cells were plated in 10-cm dishes and grown to approximately 90% confluence. Cells were washed with CO2–bicarbonate-equilibrated F-12K medium (Gibco) and incubated at 37°C for 10 min, and angioII was applied as described in the Results. The incubation was terminated by removing medium and application of 0.75 ml of an ice-cold 1 : 1 mixture of methanol and 1m HCl. Cells were then removed by scraping and mixed vigorously with 0.38 ml ice-cold chloroform in microfuge tubes. Subsequently, phospholipids were deacylated, and the head groups were separated by anion-exchange high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and quantified by suppressed conductivity as previously described (Nasuhoglu et al. 2002).

Solutions and materials

The external solution used to record Kv7 currents in CHO cells contained (mm): NaCl 160, KCl 2.5, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 1 and Hepes 10; pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. For CHO cells, the regular pipette solution contained (mm): KCl 160, MgCl2 5, Hepes 5, 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA) 0.1, K2ATP 3 and NaGTP 0.1; pH adjusted to 7.4 with KOH. In many experiments, a Ca2+-clamping ‘cocktail’ solution (CaBAPPS) was used which contained (mm): BAPTA 20, CaCl2 2, KCl 125, MgCl2 5, Hepes 5, K2ATP 3 and NaGTP 0.1, and 100 μg ml−1 pentosan polysulphate; pH adjusted to 7.4 with KOH. For current-clamp perforated-patch experiments on SCG neurons, the pipette solution contained (mm): potassium acetate 90, KCl 20, Hepes 40, MgCl2 3, EGTA 3 and CaCl2 1; pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. The bath solution contained (mm): NaCl 140, KCl 2.5, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 1, Hepes 10 and glucose 10; pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. Reagents were obtained as follows: angiotensin II, XE991, ATP GTP, pentosan polysulphate and edelfosine (Sigma); BAPTA (Molecular Probes); DMEM, fetal bovine serum, penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco).

Results

Stimulation with angiotensin increases the excitability of sympathetic neurons

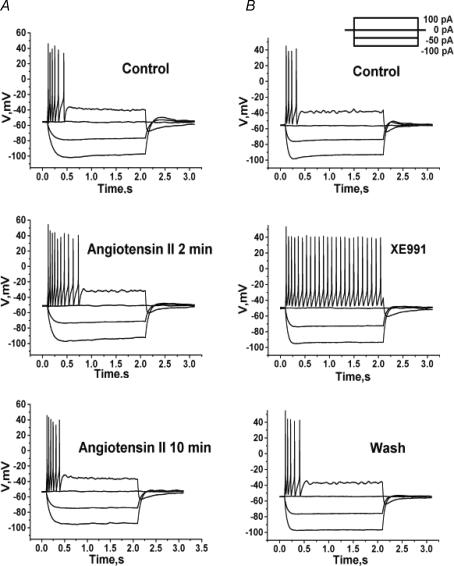

As M current in sympathetic and hippocampal neurons plays an important role in controlling excitability (Jones et al. 1995; Gu et al. 2005; Peters et al. 2005; Shen et al. 2005), the first stage of the present work was to systematically study the influence of angioII on the somatic excitability of sympathetic neurons (cultured for 2–5 days) from SCG of neonatal rats. Using perforated-patch recording, we evaluated both the active and passive properties of the neurons in response to current steps before and after application of angioII. Bath exposure to angioII had strong, but transient, effects on SCG neurons. Representative voltage recordings from positive and negative current steps are shown in Fig. 1. In control, a 100-pA current injection elicited a short train of action potentials (APs) that terminated soon after the beginning of the current step (Fig. 1A). The duration of such an AP train is thought to be determined by a balance between the inward persistent Na+ current and outward M-type and KCa K+ currents (Chen et al. 2005; Yue et al. 2005; Yue & Yaari, 2006). Application of angioII for 2 min caused an increase in the number of APs elicited by the 100-pA current step, consistent with suppression of M current. The effect was transient, as after 10 min of angioII exposure, the number of elicited APs returned to near control levels. In control, the number of APs elicited by the 100-pA depolarizing current was 2.6 ± 0.6 (n = 20). Application of angioII for 2 min increased the number of such APs to 4.7 ± 0.8 (P < 0.05, n = 12); and after 10 min of angioII exposure, the number of APs was 2.9 ± 0.4 (n = 12). For comparison, we assayed the firing properties of SCG neurons in the presence of XE991, which completely blocks M-type channels (Zaczek et al. 1998). Application of XE991 robustly increased AP firing, as expected from strong blockade of M current, with a 100-pA depolarizing current step eliciting a maintained train of APs (25.0 ± 1.8; n = 15) that lasted throughout the entire duration of current stimulus (Fig. 1B). As M channels are partially open at Vrest, we expected angioII to make Vrest less negative, and this was indeed the case (Fig. 1A and 2A). Before application of angioII, Vrest was −55.2 ± 0.4 mV (n = 20), and after 2 min of angioII application, Vrest was depolarized to −51.8 ± 0.8 mV (P < 0.01, n = 12). After 10 min of angioII application, Vrest partially recovered to −53.2 ± 0.5 mV (P < 0.05, n = 12). Application of XE991 (50 μm) depolarized Vrest to 50.0 ± 0.6 mV (P < 0.01, n = 15) (Fig. 1B and 2A).

Figure 1. AngioII increases the somatic excitability of SCG neurons.

Cultured SCG neurons were studied under perforated-patch current clamp, and voltage responses were recorded from a set of current pulses (inset). A, voltage sweeps are shown before (top), after 2 min (middle) or after 10 min (bottom) bath application of angioII (500 nm). B, voltage sweeps are shown before (top), during bath application of XE991 (10 μm) (middle) and after washout (bottom).

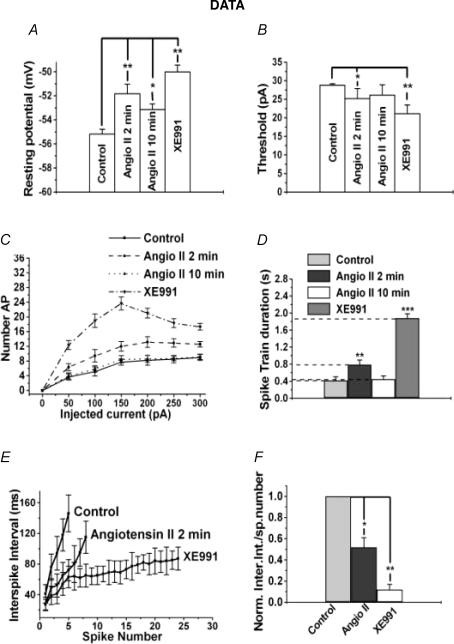

Figure 2. Analysis of effects of angioII on SCG discharge properties.

Bars show summarized measurements for neurons of the resting potential (A), the threshold current for AP generation (B), or the spike-train duration (D) in control, after 2 min or 10 min bath application of angioII, or after application of XE991. C, shows the number of APs evoked during the current step versus current amplitude for neurons in the above cases. E, shows the instantaneous interspike interval versus spike number relation for control, after 2 min application of angioII and in the presence of XE991. F, the data in E are shown normalized, calculated as the difference between the initial and final interspike interval of the spike train divided by the number of spikes.

We quantified the effects of angioII on excitability by examining the relationship between injected current and AP firing. In this analysis, we continued the use of XE991 as a strong positive control for the action of M channel closure. One such measure of excitability is the amplitude of the current required to reach threshold for action-potential generation (APthresh). In control, APthresh was 28.8 ± 0.4 pA (n = 20). Application of angioII for 2 min decreased APthresh to 25.1 ± 2.8 pA (P < 0.05, n = 12), and after 10 min of angioII exposure, APthresh somewhat recovered to 26.1 ± 1.7 pA (Fig. 2B). Exposure to XE991 decreased APthresh to 21.1 ± 2.3 pA (P < 0.05, n = 15). AngioII significantly increased the number of APs elicited over a range of injected current amplitudes (Fig. 2C). This measure of the effects of angioII on firing also showed the action to be transient, with the values at all injected current amplitudes returning to near control values after 10 min of angioII exposure. As expected, XE991 robustly increased AP generation at all stimulatory current levels.

We further characterized the regulation by angioII of neuronal discharge by assaying effects on spike-frequency adaptation (SFA) – observed as the slowing and/or cessation of a spike train driven by a long depolarizing stimulus. Under control conditions, the spike train duration in response to a 100-pA current step was 420 ± 85 ms (n = 20), and after application of angioII for 2 min, it was increased to 790 ± 105 ms (P < 0.01, n = 12) (Fig. 2D). The effect was again transient, as after a 10-min exposure to angioII, the spike-train duration recovered to 450 ± 80 ms (n = 12), which was not significantly different from controls. As expected if M current strongly influences SFA, application of XE991 dramatically increased the spike-train duration to 1880 ± 100 ms (n = 15, P < 0.001). Another measure of SFA is the relationship between instantaneous interspike interval and spike number. In control, the instantaneous interspike interval rapidly lengthened during the short spike train, but after exposure of angioII for 2 min, the slope of this relationship was shallower, and with full M channel blockade by XE991 application, the instantaneous interspike interval increased only very slowly over the dramatically lengthened spike-train duration (Fig. 2E). We quantified this parameter by approximating the slope of the relation, calculated as the difference between the initial and final interspike interval divided by the number of spikes in the train. This measure of SFA was depressed by angioII to a value 0.5 ± 0.1 (P < 0.05, n = 12) that of control (Fig. 2F). In the presence of XE991, this measure of SFA was reduced to 0.1 ± 0.1 that of control (P < 0.01, n = 15). AngioII had no significant effect on the spike half-width or amplitude, suggesting that the actions of the hormone were not mediated through modulation of voltage-gated conductances associated with the generation of individual spikes (Hille, 2001). For example, in control the spike half-width was 6.8 ± 0.3 ms, and after 2 min of angioII, it was 6.9 ± 0.3 ms. AngioII also had no significant effect on the responses to negative current steps, indicating that it does not affect the input resistance at voltages negative to M current activation. All of the angioII-induced effects on the discharge properties of these neurons are consistent with an increase in somatic excitability caused by angioII-mediated suppression of M current.

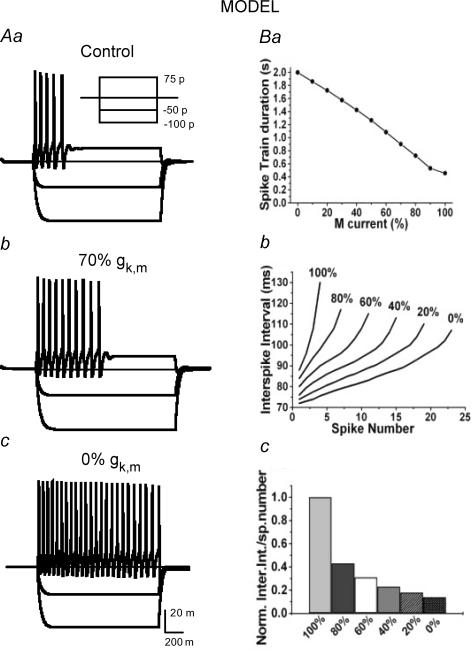

To examine whether modulation of M current alone could account for the change in excitability, we constructed a computer model of an SCG neuron to analytically evaluate the predicted effects that incremental inhibition of M channels would have on AP firing and SFA. The passive properties used for the model were chosen to approximate the input resistance and membrane time constant observed experimentally. Parameters for ionic conductances were systematically adjusted to approximate the firing behaviour of SCG neurons under control conditions (100% gK,M), with angioII-mediated 30% suppression of M current (70% gK,M), and in the presence of XE991 (complete block assumed; i.e. 0% gK,M). In the initial version of the model, only three voltage-gated conductances were employed: voltage-gated Na+ channels, a delayed rectifier K+ conductance and M current. However, in this initial simulation, the firing rate when M current was completely blocked was significantly faster than that observed experimentally and the interspike interval was uniform throughout the train, whereas in our SCG neurons, the firing rate still decreased in the presence of XE991. Insertion of a BK-type Ca2+-dependent K+ conductance (gK,Ca), along with a high-threshold voltage-gated Ca2+ conductance and intracellular calcium dynamics, more closely approximated the firing pattern at all three gK,M conductance levels. As illustrated in Fig. 3Aa–Ac, the incremental suppression of the M current conductance in the model qualitatively captured the modulation of SCG firing by angioII and XE991 observed experimentally (compare to Fig. 1). With the inclusion of gK,Ca, the effect of modulating gK,M on the spike-train duration in this model was linear (Fig. 3Ba), due to the relatively lower contribution of the M current to the total outward K+ current included in the model that included the gK,Ca conductance. Overall, the effects of M channel modulation on SFA in the model were consistent with our experimental observations. Thus, the magnitude of gK,M in the model strongly affected the relationship between instantaneous interspike interval and spike number, with an increasingly flat slope as gK,M was decreased (Fig. 3Bb and Bc). In addition, decreasing gK,M also incrementally depolarized Vrest, in a manner consistent with the experimental observations. In the simulation, a gK,M of 100%, 70% or 0% produced a Vrest of −53.5, −52.6 and −50.0 mV, respectively. As expected, varying M current had no significant effect on spike amplitude or half-width in the model. In summary, the simulations correlated well with our experimental data suggesting that the modulation of M current alone can account for the modulation of excitability by angioII.

Figure 3. A computational model of an SCG neuron simulates the effect of M channel closure on firing properties.

The data in Figs 1 and 2 were used to constrain the parameters of a computational model of an SCG neuron (see Methods) that simulated the effects on firing of various degrees of M current closure. Aa–Ac, show simulated voltage responses to the set of current injections shown in the inset in the cases of undiminished M current (control), 30% M current blockade (70% gK,M) or 100% M current blockade (0% gK,M). Ba, shows the simulated relationship between spike-train duration and percentage gK,M values. Bb, shows the simulated curves of interspike interval versus spike number at different percentage gK,M values. Bc, the slopes of the curves in Bb are normalized, as in Fig. 2F.

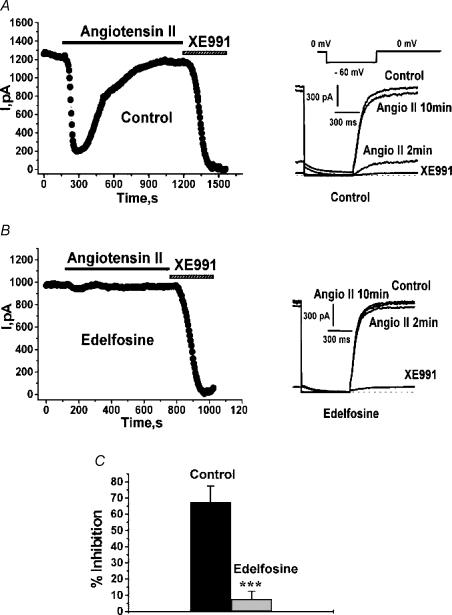

Inhibition by angiotensin II of cloned Kv7.2/7.3 channels requires PLC

The next stage of our work was to probe the molecular mechanism of action of angioII stimulation on M-type channels. As a model system to elucidate the intracellular mechanism of angioII regulation of M current, we expressed Kv7.2/7.3 heteromultimers in CHO cells by cotransfection of Kv7.2 and Kv7.3, together with AT1 receptors. Kv7.2/7.3 heteromeric channels underlie most M-type currents in sympathetic ganglia cells (Wang et al. 1998; Roche et al. 2002) and their heterologous expression produces voltage-gated K+ currents very similar to native M currents in neurons (Wang et al. 1998; Selyanko et al. 2000; Shapiro et al. 2000). Under perforated-patch recording conditions, transfected CHO cells studied using a classic M current–voltage protocol (Fig. 4A) displayed large Kv7.2/7.3 currents that were completely blocked by the specific M channel blocker XE991 (Zaczek et al. 1998). Bath application of angioII (500 nm) caused a strong suppression of the current that rebounded strongly during 10 min of continuous application of the agonist (Fig. 4A). The rebound of the Kv7.2/7.3 currents observed is consistent with the rebound of angioII-mediated effects on firing properties that we observed in SCG neurons, and with known desensitization of AT1 receptors (Thomas & Qian, 2003). As AT1 receptors couple to Gq/11, which commonly activates PLC, we verified its involvement in the angioII action on Kv7.2/7.3 channels using a PLC inhibitor, edelfosine (Powis et al. 1992). Cells were incubated with edelfosine (10 μm) for 30 min before the start of recording. In such a cell, application of angioII did not suppress the Kv7.2/7.3 current at all (Fig. 4B). In control cells, application of angioII suppressed the Kv7.2/7.3 current by 67.5 ± 9.7% (n = 7), but after incubation with edelfosine, the suppression was only 7.7 ± 4.7% (n = 9, P < 0.001; Fig. 4C). Thus, the action of angioII requires PLC activity.

Figure 4. Suppression of Kv7.2/7.3 currents in CHO cells by angioII requires PLC.

CHO cells were transiently transfected with Kv7.2 + Kv7.3 subunits and AT1 receptors and studied under perforated-patch voltage clamp. Cells were incubated for 30 min with vehicle alone (A) or edelfosine (10 μm) (B) before starting the experiment. Plotted are current amplitudes of currents elicited by the pulse protocol shown in the inset. AngioII (500 nm) or XE991 (50 μm) were bath-applied during the period indicated by the bars, and representative current traces are shown on the right. C, bars show summarized current inhibitions for control cells and for those incubated with edelfosine.

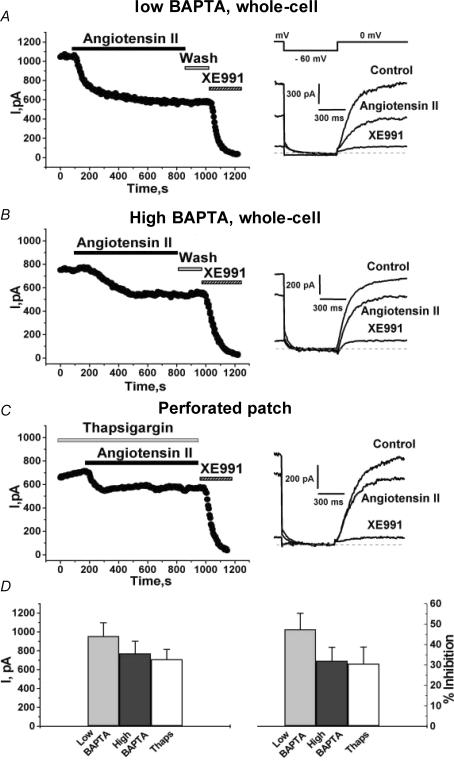

Although muscarinic (Beech et al. 1991) and angiotensin-induced (Shapiro et al. 1994) stimulations do not cause rises of Ca2+i in SCG neurons, stimulation of heterologously expressed Gq/11-coupled M1 mAChRs induces robust Ca2+i transients in mammalian cells (Shapiro et al. 2000). Likewise, stimulation of AT1 receptors expressed in CHO cells induced large Ca2+i signals, as observed using fura-2 for Ca2+ imaging (data not shown), consistent with robust activation of PLC. As the aim of our work in CHO cells was to elucidate the mechanisms of action of angioII in SCG cells, which does not involve Ca2+i signals (Shapiro et al. 1994), we performed two types of experiments to estimate the extent of the suppression of Kv7.2/7.3 current when such rises in [Ca2+]i are prevented. The first type utilized whole-cell recording conditions with a pipette solution containing either a low concentration of BAPTA, or one containing the [Ca2+]i-clamping CaBAPPS solution (Shapiro et al. 2000), containing a high concentration of BAPTA and pentosan polysulphate (PPS), a blocker of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptors (Tones et al. 1989) that prevents release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores. Using the pipette solution containing 0.1 mm BAPTA, angioII (500 nm) caused a slow, but strong suppression of the Kv7.2/7.3 current (Fig. 5A). The suppression was somewhat less than that seen in perforated-patch mode, and the current did not show an obvious rebound during angioII exposure. Using CaBAPPS as the pipette solution, CHO cells transfected with Kv7.2 + 7.3 channels and AT1 receptors responded to angioII with a substantial suppression of the Kv7.2/7.3 current that was slightly, but not significantly, lower than that with 0.1 mm BAPTA in the pipette (Fig. 5A and B). As [Ca2+]i is clamped at ∼50 nm, and cannot change, the latter inhibition must be due to a mechanism that does not involve Ca2+i signals. The second experiment used thapsigargin, a blocker of sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (Thastrup et al. 1990), in order to deplete Ca2+i stores and thus prevent Ca2+i signals (Tse et al. 1994; Cruzblanca et al. 1998; Shapiro et al. 2000). These experiments were performed on CHO cells stably expressing AT1 receptors and transiently transfected with Kv7.2 + 7.3 channels, studied under perforated-patch recording. After pre-application of thapsigargin (2 μm) for 3 min, exposure of the cells to angioII (in the continued presence of thapsigargin) still significantly suppressed the Kv7.2/7.3 current (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5. Stimulation of angioII AT1 receptors suppresses Kv7.2/7.3 channels independently of [Ca2+]i.

CHO cells were transiently transfected with Kv7.2 + 7.3 subunits and AT1 receptors (A and B), or CHO cells stably expressing AT1 receptors were transiently transfected with Kv7.2 + 7.3 subunits (C). The whole-cell configuration was used with pipettes containing either the normal (low BAPTA) (A) or ‘cocktail’ (see Methods) (B) pipette solution, or the perforated-patch mode was used (C). AngioII (500 nm), XE991 (50 μm) and thapsigargin (2 μm) were bath applied during the periods shown by the bars. Current traces in control, and after application or angioII or XE991 are shown on the right, using the indicated voltage-pulse protocol. D, shows the summarized current amplitudes (left) or percentage inhibitions (right) for these three groups of cells.

The results from all of these experiments are summarized in Fig. 5D. We evaluated both the tonic Kv7.2/7.3 current amplitudes and the current suppression by angioII. Tonic current amplitudes were not significantly different for the cells studied (1) under whole-cell clamp with 0.1 mm BAPTA in the pipette, or (2) with the CaBAPPS solution in the pipette, or (3) those treated with thapsigargin under perforated patch clamp. For these three groups of cells, the suppression of the Kv7.2/7.3 current was similar. For cells studied under whole-cell clamp with the standard, or the CaBAPPS, pipette solutions, or under perforated-patch using thapsigargin, the Kv7.2/7.3 currents were inhibited by 47.4 ± 7.9% (n = 7), 32.0 ± 6.6% (n = 12) and 30.6 ± 8.1% (n = 5), respectively (Fig. 5D). We conclude that with Ca2+i signals blocked by either manoeuvre, AT1 receptor stimulation suppresses the Kv7.2/7.3 current by 30–40%. This is somewhat less than that produced by mAChR stimulation under similar conditions (Shapiro et al. 2000), but still substantial. In the Discussion, we suggest several reasons why the inhibition seen here is different from that seen in Fig. 4.

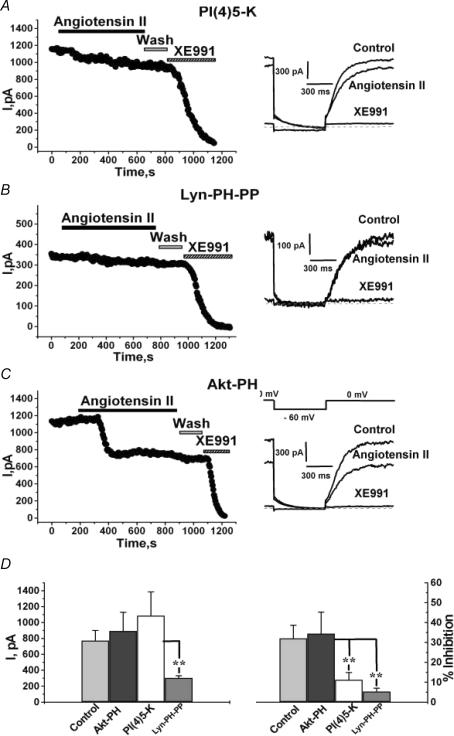

Over-expression of PI(4)5-kinase strongly reduces modulation by angioII

A number of studies have suggested that Gq/11-mediated muscarinic modulation of M-type channels and voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in sympathetic neurons is via depletion of membrane PIP2 (Suh & Hille, 2005). Given that muscarinic and angiotensin-induced stimulation in such neurons share the lack of induced Ca2+i transients, we performed several tests to determine whether the modulation by angioII of cloned Kv7.2/7.3 channels observed in the absence of Ca2+i signals likewise involves depletion of PIP2. In all of these experiments, cells were studied under whole-cell clamp using the CaBAPPS pipette solution to prevent Ca2+i signals. PIP2 is produced in the membrane by the sequential phosphorylation of phosphatidylinositol (PI) by PI4-kinase and PI(4)5-kinase. Over-expression of PI(4)5-kinase in sympathetic neurons or cardiomyocytes has been shown to strongly blunt Gq/11-mediated modulation of endogenous M current or Kir3 currents, respectively, almost certainly by increasing tonic membrane [PIP2] (Bender et al. 2002; Winks et al. 2005). We found that over-expression of PI(4)5-kinase strongly diminished modulation by angioII of Kv7.2/7.3 currents in CHO cells (Fig. 6A). In all of these types of experiments, we compared the modulation to that shown in Fig. 5 using the Ca2+-clamping CaBAPPS pipette solution (i.e. 32.0 ± 6.6%, n = 12; replotted in Fig. 6D). In cells over-expressing PI(4)5-kinase, the modulation was reduced to only 11.2 ± 3.6% (P < 0.001, n = 10). We interpret this effect as resulting from a large increase in tonic membrane abundance of PIP2 (Bender et al. 2002), such that hydrolysis of PIP2 by PLC activation does not reduce [PIP2] sufficiently in PI(4)5-kinase over-expressing cells to cause significant channel inhibition (Li et al. 2005; Winks et al. 2005). As the single-channel open probability (Po) of Kv7.2/7.3 channels at saturating voltages is in the range 0.13–0.31 (Selyanko et al. 2001; Tatulian & Brown, 2003; Li et al. 2005), an increase in tonic [PIP2] might result in greater Kv7.2/7.3 current amplitudes if maximal Po is governed by [PIP2]. However, this was not the case. For control cells, the current amplitude at 0 mV was 919 ± 189 pA (n = 12), and it was not significantly different in cells over-expressing PI(4)5-kinase (1085 ± 299 pA; n = 10). Both of these results with PI(4)5-kinase over-expression are very similar to those seen for muscarinic modulation of endogenous M current (Winks et al. 2005).

Figure 6. Over-expression of a PIP2 kinase or phosphatase affects the current amplitudes and modulation by angioII of Kv7.2/7.3 channels.

CHO cells were transiently transfected with Kv7.2 + 7.3 channels and AT1 receptors, together with the PI(4)5-kinase (A), Lyn-PH-PP (B) or Akt-PH (C) constructs. AngioII (500 nm) or XE991 (50 μm) were bath applied during the periods shown by the bars. Current traces in control, and after application or angioII or XE991 are shown on the right, using the indicated voltage-pulse protocol. D, shows the summarized current amplitudes (left) or percentage inhibitions (right) for these three groups of cells. **P < 0.01.

Over-expression of a PIP2 phosphatase strongly reduces Kv7.2/7.3 current amplitudes and blunts modulation by angioII

We then probed the role of PIP2 in regulation of Kv7.2/7.3 channels by inversely manipulating [PIP2]; that is, by over-expressing a construct (Lyn-PH-PP) containing a PIP2-specific phospholipid 5′-phosphatase (Stolz et al. 1998) that selectively reduces plasma membrane PIP2 concentrations, but not other intracellular pools of PIP2 or other plasma membrane phosphatidylinositol phosphates. It is expressed as a fusion protein to a myristoylation/palmitoylation sequence of the tyrosine kinase Lyn that causes plasma membrane localization, and to enhanced GFP (EGFP) to visualize expression (Raucher et al. 2000). If Kv7.2/7.3 channels are regulated by membrane PIP2 abundance, then one might expect tonic current amplitudes to be reduced in cells over-expressing a PIP2 phosphatase, and this was indeed the case (Fig. 6B). For cells cotransfected with Kv7.2 + 7.3 subunits and Lyn-PH-PP, whole-cell current amplitudes were reduced to 304 ± 28 pA (P < 0.01, n = 7). Expression of Lyn-PH-PP also reduced the extent of angioII modulation of those reduced currents, for which cells application of angioII (500 nm) inhibited the currents by only 5.3 ± 1.7% (P < 0.01 n = 7; Fig. 6D). This result is similar to that obtained using this same construct as a test for PIP2 depletion as the mechanism for suppression of G protein-coupled inwardly-rectifying (GIRK) K+ and N-type Ca2+ currents by Gq/11-coupled thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) and M1 muscarinic receptors, respectively (Lei et al. 2001; Gamper et al. 2004). The reduction of modulation in the cells over-expressing a PIP2 phosphatase in those studies, and reported here, suggests a tonic PIP2 abundance that is greatly reduced in cells over-expressing a PIP2 phosphatase and that subsequent activation of PLC cannot reduce the PIP2 abundance much further. The latter could well be due to concurrent receptor stimulation of phosphoinositide kinases or to feedback signals that enhance PIP2 synthesis when [PIP2] is sensed to be low (Xu et al. 2003; Gamper et al. 2004; Winks et al. 2005).

As a control, we also used another construct (Akt-PH) that contains the PH domain of the serine/threonine kinase Akt, also fused to EGFP. Akt binds to, and is activated by, PI-3 kinase-generated phosphatidylinositol 3,4-bisphosphate (PI(3,4)P2) and phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PI(3,4,5)P3), but not PIP2 (also known as PI(4,5)P2) (Franke et al. 1997). Thus, Akt-PH is a useful control for these experiments because it interacts not with PIP2, but with other doubly or triply phosphorylated phosphoinositides. Fluorescence from the Akt-PH construct was localized diffusely in the cytoplasm, as expected in cells not subjected to strong PI3-kinase stimulation (Venkateswarlu et al. 1998). Akt-PH expression had no effect on either modulation by angioII or on current amplitudes (Fig. 6C). For those cells, inhibition by angioII was 34.4 ± 10.8%, and current amplitudes were 894 ± 234 pA (n = 8; Fig. 6D). These data are consistent with modulation by angioII occurring via depletion of membrane PIP2, and reinforce the conclusion that Kv7.2/7.3 channels are sensitive to PIP2 abundance.

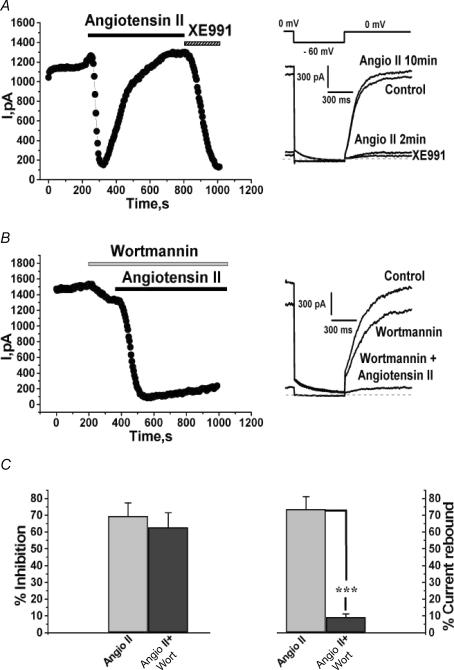

Rebound of angioII suppression of Kv7.2/7.3 currents requires PIP2 resynthesis

The effects of stimulation by angioII on the firing properties of SCG neurons studied under perforated patch clamp showed considerable rebound after 10 min of angioII exposure (Figs 1 and 2), as did the suppression of the Kv7.2/7.3 current in CHO cells studied under perforated patch clamp as shown in Fig. 4A. Our working hypothesis is that both arise from desensitization of the AT1 receptors, and subsequent turn-off of Gq/11 and PLC. If PIP2 depletion is involved in modulation by angioII of M-type channels, as suggested by the results shown in Figs. 5 and 6, then resynthesis of PIP2 should be required for rebound of the current seen during long exposures to angioII. To test this hypothesis, we compared such current rebound in the presence and absence of wortmannin, which at micromolar concentrations blocks PI4-kinase (Willars et al. 1998; Xie et al. 1999). As in the experiments shown in Fig. 4, CHO cells were cotransfected with Kv7.2 + 7.3 channels and AT1 receptors and studied under perforated-patch. As before, application of angioII induced a strong suppression of the Kv7.2/7.3 current that rebounded nearly back to baseline during 10 min of AT1 receptor stimulation (Fig. 7A). However, when cells were acutely treated with wortmannin (30 μm) just before and during application of angioII, little rebound of the Kv7.2/7.3 current was observed (Fig. 7B). There was little difference, however, in the extent of initial current suppression. Thus, angioII suppressed the Kv7.2/7.3 currents in control cells by 69.5 ± 7.7% (n = 19) and in cells treated with wortmannin by 62.7 ± 8.6% (n = 9; Fig. 7C; not significantly different at the P = 0.05 level). However, blockade of PI4-kinase strongly prevented rebound of the current during long applications of angioII. Thus, in control cells, current rebound after 10 min of angioII exposure was 73.6 ± 7.4% (n = 19), but in cells treated with wortmannin, the rebound was only 9.2 ± 1.9% (P < 0.001, n = 7; Fig. 7C). The blockade of current rebound by wortmannin provides further evidence that Kv7.2/7.3 channels are sensitive to PIP2 abundance, and that modulation by angioII involves PIP2 depletion.

Figure 7. Current rebound from AT1 receptor desensitization requires PIP2 re-synthesis.

A and B, CHO cells stably expressing AT1 receptors were transiently transfected with Kv7.2 + 7.3 subunits and studied under perforated patch. AngioII (500 nm), XE991 (50 μm) and wortmannin (30 μm) were bath applied during the periods shown by the bars. Current traces at the indicated times are shown on the right, using the voltage-pulse protocol shown above. C, shows the percentage inhibitions (left) or the percentage current rebound after the presumed desensitization of the AT1 receptors (right) for these two groups of cells. ***P < 0.001.

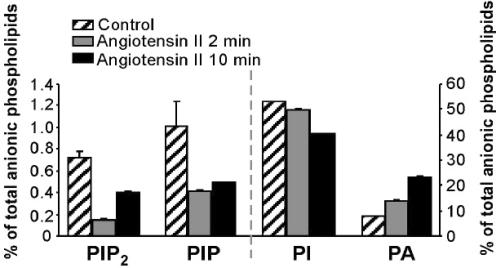

Stimulation of angiotensin AT1 receptors in CHO cells depletes PIP2

In the case of PIP2-depletion, a significant reduction in PIP2 abundance would be required to cause the suppression of the currents that is seen. To ascertain whether such angioII-mediated reduction in PIP2 abundance actually occurs, we used our CHO cell line stably expressing AT1 receptors to analytically measure changes in phosphoinositide abundance induced by stimulation of these cells with angiotensin. Using HPLC analysis, we assayed the abundance of several different phosphoinositides, including PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PIP), PI and phosphatidic acid (PA) before and after exposure of the cells to angioII (2 μm) for 2 or 10 min. We found that stimulation by angiotensin for 2 min indeed greatly reduced the abundance of PIP2, as well as PIP (Fig. 8). In accord with the rebound of SCG discharge properties and with the rebound of Kv7.2/7.3 currents in CHO cells studied under perforated patch, there was substantial rebound in the abundance PIP2 and PIP after 10 min of exposure to angioII. Results are given as percentages of total anionic phospholipids, a pool that includes phosphatidylserine and cardiolipin, which are not directly involved in PLC activity. The percentage of PIP2 was reduced from 0.72 ± 0.07% in control to 0.15 ± 0.04% after 2 min of angioII exposure (n = 4). Receptor stimulation also caused a modest decline in the percentage of PIP, from 1.00 ± 0.23% before to 0.42 ± 0.04% after 2 min of angioII exposure (n = 4). Unexpectedly, the percentage of PI also displayed a significant decline, falling from 53.3 ± 0.5% before to 49.7 ± 0.5% after 2 min of angioII exposure. As diacylglycerol (DAG), the membrane-bound by-product of PIP2 hydrolysis, is rapidly converted to PA by DAG kinase, the percentage of PA increased upon receptor stimulation, as expected. The percentage of PA rose from 7.7 ± 0.5% in control to 13.7 ± 0.4% (n = 5) after 2 min of angioII exposure. We found the abundance of PIP2, and to a lesser extent PIP, slowly rebounded during maintained stimulation with angioII. Thus, the percentage of PIP2 and the percentage of PIP recovered to 0.40 ± 0.04% (n = 4) and 0.49 ± 0.03% (n = 5) after 10 min of angioII exposure, respectively. The percentage of PI, however, continued to fall during maintained receptor stimulation, falling to 40.3 ± 0.2% (n = 4) after 10 min of angioII exposure. The percentage of PA also continued to rise during the maintained stimulation, rising further to 23.2 ± 0.5% (n = 4) after 10 min of angioII exposure (Fig. 8). On the one hand, the partial recovery of the percentages of PIP2 and PIP during the 10-min angioII treatment is consistent with the known desensitization of AT1 receptors and with the rebound of SCG discharge properties, and of suppression of Kv7.2/7.3 currents in CHO cells studied under perforated patch, during similar 10-min angioII applications. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that this partial recovery is due to the agonist-mediated stimulation of PIP and PIP2 synthesis (Xu et al. 2003; Gamper et al. 2004). Indeed, the continued fall in the percentage of PI and the continued rise in the percentage of PA could suggest that PIP2 hydrolysis continued unabated during the longer exposure to angioII, arguing against receptor desensitization as the reason for the partial recovery of the percentages of PIP2 and PIP during the 10-min treatment. Another explanation may be PIP2 synthesis in a membrane domain that the channels do not have access to, such as organelle membrane. Further, more spatially compartmentalized experiments may be required to fully correlate the time course of the abundance of lipid molecules during receptor stimulation with the varying degrees of desensitization seen in neuronal discharge properties, and in M-type channel modulation.

Figure 8. Stimulation of cloned AT1 receptors depletes PIP2.

CHO cells stably expressing AT1 receptors were stimulated with angioII (2 μm) for 2 or 10 min. Bars show the fractional abundance of anionic phospholipids at the indicated times, expressed as a percentage of the total pool. The left ordinate is for the PIP2 and PIP data, and the right ordinate is for the PI and PA data.

Discussion

In this work, we investigated the physiological and molecular mechanism of angioII-dependent modulation of excitability by M-type channels. Consistent with an important role of M currents in regulating neuronal excitability, stimulation by angioII greatly increased excitability of SCG neurons and reduced SFA. These effects were simulated in a computational model where only the M current conductance was modulated. We also investigated whether depletion of PIP2 is the likely mechanism of modulation of Kv7 channels by stimulation of angioII AT1 receptors. Indeed, manipulation of tonic PIP2 levels by manipulation of PIP2 kinase or phosphatases in CHO cells heterologously expressing cloned Kv7.2/7.3 channels and AT1 receptors had effects consistent with PIP2 involvement in the action of angioII. Finally, HPLC analysis confirmed that stimulation of cloned AT1 receptors strongly reduces the fractional PIP2 (and PIP) abundance, similar to that caused by muscarinic stimulation in the same cells (Horowitz et al. 2005; Li et al. 2005). Taken together, these results were consistent with PIP2-regulated M channels and with AT1-receptor stimulation causing depletion of membrane PIP2 levels.

Of the four well-described Gq/11-coupled receptors in SCG neurons that have been shown to modulate M current, suppression by the muscarinic M1 receptor has received by far the most attention. Such muscarinic suppression has now been established as being primarily due to depletion of membrane PIP2 levels (reviewed by Delmas et al. (2005)). In SCG neurons, the mechanisms of M1 receptor- and AT1 receptor-mediated suppression of both M-type K+ and N-type Ca2+ channels seem to be very similar. The similarities include a similar slow, Gαq/11-mediated inhibition of both channels and the lack of rise in [Ca2+]i induced by stimulation of either receptor (Shapiro et al. 1994; Haley et al. 1998). In contrast, bradykinin B2 and purinergic P2Y receptors, which cause increases in [Ca2+]i and suppress M current only when IP3-mediated Ca2+i signals are allowed to occur (Cruzblanca et al. 1998; Bofill-Cardona et al. 2000), probably do not deplete PIP2, as a result of Ca2+i-mediated stimulation of PIP2 synthesis (Gamper et al. 2004; Winks et al. 2005). Thus, in our thinking, Gq/11-coupled receptors are divided into two classes which act on channels via distinct mechanisms. Both classes activate PLC, and hydrolyse PIP2, but our working hypothesis is that the receptors that cause [Ca2+]i rises in neurons act primarily via those Ca2+i signals, not via depletions of PIP2, whereas the class that does not release Ca2+ primarily acts via PIP2 depletion, a difference that is thought to be due to compartmentalization of signalling proteins into distinct microdomains (Delmas et al. 2005).

The angioII-induced increase in excitability of SCG cells, as characterized by depolarization of Vrest, reduced threshold, increased AP number, and reduced SFA, is in accord with a prominent role by M channels in the control of neuronal excitability (Jones et al. 1995; Cooper et al. 2001; Shen et al. 2005). Indeed, in our computational model, a moderate reduction of gK.M is predicted to have a profound effect on the firing pattern of SCG neurons. Changes to the electrophysiological properties of SCG resulting from stimulation by angioII all indicate a lowered threshold for AP generation and a reduction in the braking effect of M channels on neuronal discharge. This is consistent with long-standing evidence suggesting a strong excitatory effect of angioII on a variety of neurons, including the classic indicator of SCG outputs to the nictitating membrane of the cat (Buckley, 1972; Reit, 1972). The latter study, observing the contraction of the ipsilateral membrane as an indicator of ganglionic excitation, found angioII-induced stimulation to be strongly excitatory, as was bradykinin-induced stimulation. Much new work also indicates strong control of M-type channels specifically in SFA (Yue & Yaari, 2004; Gu et al. 2005; Peters et al. 2005), which we observed as a dramatic increase in spike-train duration, and a decrease in inter-spike intervals caused by M channel closure.

The functional view of sympathetic neurons has generally been one of a relay circuit, conveying information through a cholinergic synapse towards a peripheral target. Less attention has been paid to their integrative capabilities, in spite of the fact that they have long been one of the major model systems for studying the modulation of membrane excitability through control of M channels. Indeed, the expression of a long-lasting form of synaptic enhancement at cholinergic synapses further argues for an integrative role (reviewed by Alkadhi et al. (2005)). Why would a synapse change strength if its postsynaptic potential always triggers a spike? There is evidence to suggest that synaptic gain (i.e. the increased output firing rate relative to the frequency of synaptic input), can be produced in autonomic ganglia by the presence of subthreshold excitatory input (McLachlan & Meckler, 1989; Karila & Horn, 2000; McLachlan, 2003). Through a combination of experimental work and computational modelling, it has recently been shown that enhancing membrane excitability, such as through the modulation of M channels, augments such synaptic gain (Wheeler et al. 2004).

In our experiments on cloned Kv7.2/7.3 channels expressed in CHO cells, we saw a marked difference in the extent of current rebound during long exposures to angioII. Thus, of 44 CHO cells studied under whole-cell voltage clamp, only 9% displayed any obvious rebound of the suppressed current, whereas of 40 cells studied under perforated patch clamp, 70% displayed this aspect of the Kv7.2/7.3 channel modulation. The rebound of Kv7.2/7.3 current suppression seen in perforated patch clamp experiments is in accord with the similar rebound of altered SCG discharge properties observed similarly in perforated patch mode, and with studies showing robust desensitization of angioII AT1 receptors. Might the whole-cell recording with the CaBAPPS pipette solution have masked a desensitization of AT1 receptor-mediated modulation of M-type channels present in intact cells? In fact, such AT1-receptor desensitization has been described and is mediated via G-protein-receptor kinases and β-arrestins (Olivares-Reyes et al. 2001; Thomas & Qian, 2003), molecules that may dialyse from the cytoplasm during whole-cell recording, explaining the differential current rebound between whole-cell and perforated-patch recording modes. Also implicated in AT1 receptor desensitization are intracellular Ca2+ signals, in concert with calmodulin (Sallese et al. 2000). Thus, in the perforated-patch current-clamp recordings of SCG cells, as for the perforated-patch experiments on CHO cells not treated with thapsigargin (in which the intracellular milieu was undisturbed), desensitization of AT1-receptor actions was more pronounced.

We also observed a greater inhibition of the cloned Kv7.2/7.3 channels expressed in CHO cells in which [Ca2+]i was not controlled, probably due to Ca2+-dependent stimulation of PLC when [Ca2+]i rises are permitted. Indeed, Horowitz et al. (2005), assaying the Ca2+-dependence of PIP2 hydrolysis by monitoring translocation of the widely used PLCδ-PH PIP2/IP3 probe (Nahorski et al. 2003), found the translocation, and thus PIP2 hydrolysis, to be significantly reduced when [Ca2+]i was clamped with BAPTA, or stores were depleted with thapsigargin, as in the experiments reported herein. Moreover, recent work implicates PIP2 depletion as the mechanism of desensitization of TrpM4 channels induced by rises in [Ca2+]i that activate PLC, in this case without stimulation of any receptor (Zhang et al. 2005; Nilius et al. 2006). Thus, although we have shown Kv7.2/7.3 channels to be sensitive to [Ca2+]i when partnered with calmodulin (Gamper & Shapiro, 2003), we suggest the increase in inhibition seen in Figs 4 and 7 to be mostly from the acceleration of PLC activity from the likely robust Ca2+i signals in those intact cells.

Overall, the HPLC results are very similar to those recently obtained from stimulation of muscarinic M1 receptors using the same cells (Horowitz et al. 2005; Li et al. 2005). The decrease in the percentage of PIP2 caused by angioII-induced stimulation of AT1 receptor-expressing CHO cells in this study was similar in magnitude to that caused by muscarinic stimulation of M1R-expressing CHO cells in those studies. In addition, the rebounds in the phosphoinositide abundance caused by muscarinic and angiotensin-induced stimulation were similar. Although M1 receptor-mediated suppression of M current is not known to desensitize, desensitization of muscarinic receptors in general, and M1 receptors in particular, is well documented (van Koppen & Kaiser, 2003). However, we cannot be sure that there is not some bias towards rebound in our HPLC analysis. What we can conclude from these measurements is that stimulation of both types of receptors can substantially deplete CHO cells of PIP2, consistent with PIP2 depletion causing inhibition of these PIP2-sensitive channels. Furthermore, with Ca2+i signals prevented, muscarinic stimulation caused 70–80% inhibition of expressed Kv7.2/7.3 channels (Shapiro et al. 2000; Suh & Hille, 2002; Gamper et al. 2003), but stimulation by angioII in the present study only caused about half of that. If suppression of the Kv7.2/7.3 current is by PIP2 depletion, and such depletions are similar, then one would expect a more parallel degree of inhibition. One explanation for the difference could be the clustering of certain receptors into microdomains containing local ‘hotspots’ of PIP2, as has been suggested for PIP2 regulation of Kir K+ channels (Cho et al. 2005). In that scenario, the local concentration of PIP2 near channels could change less upon application of angioII, than upon muscarinic stimulation, even though global depletions measured by HPLC would be the same. Further measurements of the mobility of PIP2 molecules in the membrane, of the homogeneity of lipid molecules, and of the biochemical affinities of phosphoinositides for the channel proteins, will be required to fully address these issues.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pamela Martin, Kathryn Boyd, Ping Dong and Chengcheng Shen for expert technical assistance. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 NS043394 (M.S.S.) and R01 HL067942 (D.W.H.), an American Heart Association postdoctoral fellowship 0325120Y (N.G.), and a San Antonio Life Sciences Initiative (SALSI) grant (M.S.S. and D.B.J.).

References

- Aileru AA, Logan E, Callahan M, Ferrario CM, Ganten D, Diz DI. Alterations in sympathetic ganglionic transmission in response to angiotensin II in (mRen2)27 transgenic rats. Hypertension. 2004;43:270–275. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000112422.81661.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akasu T, Hirai K, Koketsu K. Modulatory actions of ATP on membrane potentials of bullfrog sympathetic ganglion cells. Brain Res. 1983;258:313–317. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)91157-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkadhi KA, Alzoubi KH, Aleisa AM. Plasticity of synaptic transmission in autonomic ganglia. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;75:83–108. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech DJ, Bernheim L, Mathie A, Hille B. Intracellular Ca2+ buffers disrupt muscarinic suppression of Ca2+ current and M current in rat sympathetic neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:652–656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.2.652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender K, Wellner-Kienitz MC, Pott L. Transfection of a phosphatidyl-4-phosphate 5-kinase gene into rat atrial myocytes removes inhibition of GIRK current by endothelin and alpha-adrenergic agonists. FEBS Lett. 2002;529:356–360. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03426-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernheim L, Beech DJ, Hille B. A diffusible second messenger mediates one of the pathways coupling receptors to calcium channels in rat sympathetic neurons. Neuron. 1991;6:859–867. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90226-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bofill-Cardona E, Vartian N, Nanoff C, Freissmuth M, Boehm S. Two different signaling mechanisms involved in the excitation of rat sympathetic neurons by uridine nucleotides. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57:1165–1172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg-Graham L. Modelling the non-linear conductances of excitable membranes. In: Chad J, Wheal H, editors. Cellular Neurobiology:a Practical Approach. Vol. 13. Oxford: IRL Press at. Oxford University Press; 1991. pp. 247–275. [Google Scholar]

- Brown DA, Adams PR. Muscarinic suppression of a novel voltage-sensitive K+ current in a vertebrate neurone. Nature. 1980;283:673–676. doi: 10.1038/283673a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley JP. Actions of angiotensin on the central nervous system. Fed Proc. 1972;31:1332–1337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Yue C, Yaari Y. A transitional period of Ca2+-dependent spike afterdepolarization and bursting in developing rat CA1 pyramidal cells. J Physiol. 2005;567:79–93. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.084590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Lee D, Lee SH, Ho WK. Receptor-induced depletion of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate inhibits inwardly rectifying K+ channels in a receptor-specific manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4643–4648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408844102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constanti A, Brown DA. M-currents in voltage-clamped mammalian sympathetic neurones. Neurosci Lett. 1981;24:289–294. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(81)90173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper EC, Harrington E, Jan YN, Jan LY. M channel KCNQ2 subunits are localized to key sites for control of neuronal network oscillations and synchronization in mouse brain. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9529–9540. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-09529.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruzblanca H, Koh DS, Hille B. Bradykinin inhibits M current via phospholipase C and Ca2+ release from IP3-sensitive Ca2+ stores in rat sympathetic neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7151–7156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmas P, Brown DA. Pathways modulating neural KCNQ/M (Kv7) potassium channels. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:850–862. doi: 10.1038/nrn1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmas P, Coste B, Gamper N, Shapiro MS. Phosphoinositide lipid second messengers: new paradigms for calcium channel modulation. Neuron. 2005;47:179–182. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmas P, Wanaverbecq N, Abogadie FC, Mistry M, Brown DA. Signaling microdomains define the specificity of receptor-mediated InsP3 pathways in neurons. Neuron. 2002;34:209–220. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00641-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippov AK, Selyanko AA, Robbins J, Brown DA. Activation of nucleotide receptors inhibits M-type K current [IK(M)] in neuroblastoma x glioma hybrid cells. Pflugers Arch. 1994;429:223–230. doi: 10.1007/BF00374316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford CP, Stemkowski PL, Light PE, Smith PA. Experiments to test the role of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in neurotransmitter-induced M-channel closure in bullfrog sympathetic neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4931–4941. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-04931.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke TF, Kaplan DR, Cantley LC, Toker A. Direct regulation of the Akt proto-oncogene product by phosphatidylinositol-3,4-bisphosphate. Science. 1997;275:665–668. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamper N, Li Y, Shapiro MS. Structural requirements for differential sensitivity of KCNQ K+ channels to modulation by Ca2+/calmodulin. Mol Biol Cell. 2005a;16:3538–3551. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-09-0849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamper N, Reznikov V, Yamada Y, Yang J, Shapiro MS. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate signals underlie receptor-specific Gq/11-mediated modulation of N-type Ca2+ channels. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10980–10992. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3869-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamper N, Shapiro MS. Calmodulin mediates Ca2+-dependent modulation of M-type K+ channels. J Gen Physiol. 2003;122:17–31. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200208783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamper N, Stockand JD, Shapiro MS. Subunit-specific modulation of KCNQ potassium channels by Src tyrosine kinase. J Neurosci. 2003;23:84–95. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-01-00084.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamper N, Stockand JD, Shapiro MS. The use of Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells in the study of ion channels. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2005b;51:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu N, Vervaeke K, Hu H, Storm JF. Kv7/KCNQ/M and HCN/h, but not KCa2/SK channels, contribute to the somatic medium after-hyperpolarization and excitability control in CA1 hippocampal pyramidal cells. J Physiol. 2005;566:689–715. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.086835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley JE, Abogadie FC, Delmas P, Dayrell M, Vallis Y, Milligan G, Caulfield MP, Brown DA, Buckley NJ. The alpha subunit of Gq contributes to muscarinic inhibition of the M-type potassium current in sympathetic neurons. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4521–4531. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-12-04521.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Sunderland, MA: Sinaver Associates; 2001. Ionic channels of excitable membranes. [Google Scholar]

- Hines ML, Carnevale NT. NEURON: a tool for neuroscientists. Neuroscientist. 2001;7:123–135. doi: 10.1177/107385840100700207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz LF, Hirdes W, Suh BC, Hilgemann DW, Mackie K, Hille B. Phospholipase C in living cells: activation, inhibition, Ca2+ requirement, and regulation of M current. J Gen Physiol. 2005;126:243–262. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S, Brown DA, Milligan G, Willer E, Buckley NJ, Caulfield MP. Bradykinin excites rat sympathetic neurons by inhibition of M current through a mechanism involving B2 receptors and Gαq/11. Neuron. 1995;14:399–405. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90295-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karila P, Horn JP. Secondary nicotinic synapses on sympathetic B neurons and their putative role in ganglionic amplification of activity. J Neurosci. 2000;20:908–918. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-03-00908.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Q, Talley EM, Bayliss DA. Receptor-mediated inhibition of G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying potassium channels involves Gαq family subunits, phospholipase C, and a readily diffusible messenger. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16720–16730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100207200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerche C, Scherer CR, Seebohm G, Derst C, Wei AD, Busch AE, Steinmeyer K. Molecular cloning and functional expression of KCNQ5, a potassium channel subunit that may contribute to neuronal M-current diversity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:22395–22400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002378200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Gamper N, Hilgemann DW, Shapiro MS. Regulation of Kv7 (KCNQ) K+ channel open probability by phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9825–9835. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2597-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan EM. Transmission of signals through sympathetic ganglia – modulation, integration or simply distribution? Acta Physiol Scand. 2003;177:227–235. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan EM, Meckler RL. Characteristics of synaptic input to three classes of sympathetic neurone in the coeliac ganglion of the guinea-pig. J Physiol. 1989;415:109–129. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JC, Schofield GG. Alterations of synaptic transmission in sympathetic ganglia of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:R1397–R1407. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.267.5.R1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrion NV. Control of M-current. Annu Rev Physiol. 1997;59:483–504. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliore M, Cook EP, Jaffe DB, Turner DA, Johnston D. Computer simulations of morphologically reconstructed CA3 hippocampal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1995;73:1157–1168. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.3.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahorski SR, Young KW, John Challiss RA, Nash MS. Visualizing phosphoinositide signalling in single neurons gets a green light. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:444–452. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00178-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasuhoglu C, Feng S, Mao J, Yamamoto M, Yin HL, Earnest S, Barylko B, Albanesi JP, Hilgemann DW. Nonradioactive analysis of phosphatidylinositides and other anionic phospholipids by anion-exchange high-performance liquid chromatography with suppressed conductivity detection. Anal Biochem. 2002;301:243–254. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B, Mahieu F, Prenen J, Janssens A, Owsianik G, Vennekens R, Voets T. The Ca2+-activated cation channel TRPM4 is regulated by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate. EMBO J. 2006;25:467–478. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivares-Reyes JA, Smith RD, Hunyady L, Shah BH, Catt KJ. Agonist-induced signaling, desensitization, and internalization of a phosphorylation-deficient AT1A angiotensin receptor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37761–37768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106368200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters HC, Hu H, Pongs O, Storm JF, Isbrandt D. Conditional transgenic suppression of M channels in mouse brain reveals functions in neuronal excitability, resonance and behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:51–60. doi: 10.1038/nn1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powis G, Seewald MJ, Gratas C, Melder D, Riebow J, Modest EJ. Selective inhibition of phosphatidylinositol phospholipase C by cytotoxic ether lipid analogues. Cancer Res. 1992;52:2835–2840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rae J, Cooper K, Gates P, Watsky M. Low access resistance perforated patch recordings using amphotericin B. J Neurosci Methods. 1991;37:15–26. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(91)90017-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raucher D, Stauffer T, Chen W, Shen K, Guo S, York JD, Sheetz MP, Meyer T. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate functions as a second messenger that regulates cytoskeleton-plasma membrane adhesion. Cell. 2000;100:221–228. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81560-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reit E. Actions of angiotensin on the adrenal medulla and autonomic ganglia. Fed Proc. 1972;31:1338–1343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche JP, Westenbroek R, Sorom AJ, Hille B, Mackie K, Shapiro MS. Antibodies and a cysteine-modifying reagent show correspondence of M current in neurons to KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 K+ channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;137:1173–1186. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallese M, Iacovelli L, Cumashi A, Capobianco L, Cuomo L, De Blasi A. Regulation of G protein-coupled receptor kinase subtypes by calcium sensor proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1498:112–121. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(00)00088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selyanko AA, Hadley JK, Brown DA. Properties of single M-type KCNQ2/KCNQ3 potassium channels expressed in mammalian cells. J Physiol. 2001;534:15–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selyanko AA, Hadley JK, Wood IC, Abogadie FC, Jentsch TJ, Brown DA. Inhibition of KCNQ1-4 potassium channels expressed in mammalian cells via M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. J Physiol. 2000;522:349–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-2-00349.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro MS, Roche JP, Kaftan EJ, Cruzblanca H, Mackie K, Hille B. Reconstitution of muscarinic modulation of the KCNQ2/KCNQ3 K+ channels that underlie the neuronal M current. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1710–1721. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-05-01710.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro MS, Wollmuth LP, Hille B. Angiotensin II inhibits calcium and M current channels in rat sympathetic neurons via G proteins. Neuron. 1994;12:1319–1329. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90447-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W, Hamilton SE, Nathanson NM, Surmeier DJ. Cholinergic suppression of KCNQ channel currents enhances excitability of striatal medium spiny neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7449–7458. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1381-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolz LE, Kuo WJ, Longchamps J, Sekhon MK, York JD. INP51, a yeast inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase required for phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate homeostasis and whose absence confers a cold-resistant phenotype. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:11852–11861. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.19.11852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh B, Hille B. Recovery from muscarinic modulation of M current channels requires phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate synthesis. Neuron. 2002;35:507–520. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00790-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh B-C, Hille B. Regulation of ion channels by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:370–378. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh BC, Horowitz LF, Hirdes W, Mackie K, Hille B. Regulation of KCNQ2/KCNQ3 current by G-protein cycling: the kinetics of receptor-mediated signaling by Gq. J Gen Physiol. 2004;123:663–683. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatulian L, Brown DA. Effect of the KCNQ potassium channel opener retigabine on single KCNQ2/3 channels expressed in CHO cells. J Physiol. 2003;549:57–63. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.039842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thastrup O, Cullen PJ, Drobak BK, Hanley MR, Dawson AP. Thapsigargin, a tumor promoter, discharges intracellular Ca2+ stores by specific inhibition of the endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:2466–2470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas WG, Qian H. Arresting angiotensin type 1 receptors. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2003;14:130–136. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(03)00023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokimasa T, Akasu T. ATP regulates muscarine-sensitive potassium current in dissociated bull-frog primary afferent neurones. J Physiol. 1990;426:241–264. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tones MA, Bootman MD, Higgins BF, Lane DA, Pay GF, Lindahl U. The effect of heparin on the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor in rat liver microsomes. Dependence on sulphate content and chain length. FEBS Lett. 1989;252:105–108. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)80898-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub RD, Wong RK, Miles R, Michelson H. A model of a CA3 hippocampal pyramidal neuron incorporating voltage-clamp data on intrinsic conductances. J Neurophysiol. 1991;66:635–650. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.66.2.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse A, Tse FW, Hille B. Calcium homeostasis in identified rat gonadotrophs. J Physiol. 1994;477:511–525. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Koppen CJ, Kaiser B. Regulation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor signaling. Pharmacol Ther. 2003;98:197–220. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(03)00032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkateswarlu K, Gunn-Moore F, Oatey PB, Tavare JM, Cullen PJ. Nerve growth factor- and epidermal growth factor-stimulated translocation of the ADP-ribosylation factor-exchange factor GRP1 to the plasma membrane of PC12 cells requires activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and the GRP1 pleckstrin homology domain. Biochem J. 1998;335:139–146. doi: 10.1042/bj3350139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HS, Pan Z, Shi W, Brown BS, Wymore RS, Cohen IS, Dixon JE, McKinnon D. KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 potassium channel subunits: molecular correlates of the M-channel. Science. 1998;282:1890–1893. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler DW, Kullmann PH, Horn JP. Estimating use-dependent synaptic gain in autonomic ganglia by computational simulation and dynamic-clamp analysis. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:2659–2671. doi: 10.1152/jn.00470.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willars GB, Nahorski SR, Challis RA. Differential regulation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor-sensitive polyphosphoinositide pools and consequences for signaling in human neuroblastoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5037–5046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.5037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winks JS, Hughes S, Filippov AK, Tatulian L, Abogadie FC, Brown DA, Marsh SJ. Relationship between membrane phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate and receptor-mediated inhibition of native neuronal M channels. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3400–3413. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3231-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie LH, Horie M, Takono M. Phospholipase C-linked receptors regulate the ATP-sensitive potassium channel by means of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:15292–15297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Watras J, Loew LM. Kinetic analysis of receptor-activated phosphoinositide turnover. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:779–791. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200301070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarowsky P, Weinreich D. Loss of accommodation in sympathetic neurons from spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1985;7:268–276. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.7.2.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue C, Remy S, Su H, Beck H, Yaari Y. Proximal persistent Na+ channels drive spike afterdepolarizations and associated bursting in adult CA1 pyramidal cells. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9704–9720. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1621-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue C, Yaari Y. KCNQ/M channels control spike afterdepolarization and burst generation in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4614–4624. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0765-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue C, Yaari Y. Axo-somatic and apical dendritic Kv7/M channels differentially regulate the intrinsic excitability of adult rat CA1 pyramidal cells. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:3480–3495. doi: 10.1152/jn.01333.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaczek R, Chorvat RJ, Saye JA, Pierdomenico ME, Maciag CM, Logue AR, Fisher BN, Rominger DH, Earl RA. Two new potent neurotransmitter release enhancers, 10,10-bis(4-pyridinylmethyl)-9(10H)-anthracenone and 10,10-bis(2-fluoro-4-pyridinylmethyl)-9(10H)-anthracenone: comparison to linopirdine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;285:724–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Craciun LC, Mirshahi T, Rohacs T, Lopes CM, Jin T, Logothetis DE. PIP2 activates KCNQ channels, and its hydrolysis underlies receptor-mediated inhibition of M currents. Neuron. 2003;37:963–975. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Okawa H, Wang Y, Liman ER. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate rescues TRPM4 channels from desensitization. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39185–39192. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506965200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]