Abstract

Hippocampal inhibitory interneurones demonstrate pathway- and synapse-specific rules of transmission and plasticity, which are key determinants of their role in controlling pyramidal cell excitability. Mechanisms underlying long-term changes at interneurone excitatory synapses, despite their importance, remain largely unknown. We use two-photon calcium imaging and whole-cell recordings to determine the Ca2+ signalling mechanisms linked specifically to group I metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR1α and mGluR5) and their role in hebbian long-term potentiation (LTP) in oriens/alveus (O/A) interneurones. We demonstrate that mGluR1α activation elicits dendritic Ca2+ signals resulting from Ca2+ influx via transient receptor potential (TRP) channels and Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. By contrast, mGluR5 activation produces dendritic Ca2+ transients mediated exclusively by intracellular Ca2+ release. Using Western blot analysis and immunocytochemistry, we show mGluR1α-specific extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK1/2) activation via Src in CA1 hippocampus and, in particular, in O/A interneurones. Moreover, we find that mGluR1α/TRP Ca2+ signals in interneurone dendrites are dependent on activation of the Src/ERK cascade. Finally, this mGluR1α-specific Ca2+ signalling controls LTP at interneurone synapses since blocking either TRP channels or Src/ERK and intracellular Ca2+ release prevents LTP induction. Thus, our findings uncover a novel molecular mechanism of interneurone-specific Ca2+ signalling, critical in regulating synaptic excitability in hippocampal networks.

Hippocampal inhibitory interneurones are a hetero-geneous cell group forming complex local circuit networks with principal neurones (Freund & Buzsaki, 1996). The rules of transmission and plasticity at interneurone excitatory synapses are exquisitely pathway- and synapse-specific (Maccaferri et al. 1998; Scanziani et al. 1998; Toth & McBain, 1998). Long-term potentiation (LTP), induced at certain interneurone excitatory synapses (Alle et al. 2001; Perez et al. 2001), regulates inhibition of principal cells (Lapointe et al. 2004) and maintains fidelity of signal processing in hippocampus (Lamsa et al. 2005). In CA1 interneurones of stratum oriens/alveus (O/A), LTP is induced by coincident pre- and postsynaptic activity. It occurs at Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptor (CP-AMPAR) containing synapses, involves activation of metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR) subtype 1α, and requires a postsynaptic Ca2+ elevation ([Ca2+]i) (Perez et al. 2001; Lapointe et al. 2004). Group I mGluRs (mGluR1 and mGluR5), but not CP-AMPARs, contribute to the [Ca2+]i increase during LTP induction (Topolnik et al. 2005). However, Ca2+ signals activated selectively by each subtype of group I mGluRs and the Ca2+ signal specifically involved in LTP induction at interneurone excitatory synapses, remain undetermined.

A well-established pathway of mGluR1/5 Ca2+ signalling is G-protein-dependent intracellular Ca2+ release via phospholipase C (PLC) and inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) activation (Pin & Duvoisin, 1995; Hermans & Challiss, 2001). This Ca2+ signal regulates the induction of many forms of LTP (Bortolotto & Collingridge, 1993; Emptage, 1999; Nakamura et al. 1999). Moreover, mGluR1 can be linked with a member of the canonical subfamily of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels in cerebellar Purkinje neurones (TRPC1; Kim et al. 2003). In O/A interneurones, mGluR1/5-mediated Ca2+ signalling involves release from ryanodine-sensitive stores (Woodhall et al. 1999). In addition, mGluR1/5 Ca2+ transients are associated with outwardly rectifying currents (Topolnik et al. 2005) similar to those of TRPC1/TRPC5 heteromultimeric channels (Strübing et al. 2001). TRPC1/5 channels are activated by Gq-protein coupled receptors (Strubing et al. 2001; Clapham, 2003) and may provide receptor-regulated Ca2+ influx (Clapham, 2003). Both TRPC proteins have overlapping distributions in hippocampus (Strubing et al. 2001) and could be involved in mGluR1 Ca2+ signalling and LTP induction in interneurones.

Interestingly, in addition to the well-established G-protein-dependent signalling cascade, mGluR1/5 also signal via Src-family tyrosine kinases (Heuss et al. 1999). Furthermore, both mGluR1 and mGluR5 are linked via Src to the extracellular-signal regulated kinase (ERK)/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade (Thandi et al. 2002; Zhao et al. 2004). ERK is involved in synaptic plasticity and memory formation and affects many targets, including transcription factors, cytoskeletal proteins and ion channels (Grewal et al. 1999; Yuan et al. 2002; Sweatt, 2004). However, its role in Ca2+ signalling remains unexplored.

Thus, our goals were to (1) characterize Ca2+ mechanisms linked specifically to mGluR1 and mGluR5 in O/A interneurones, (2) examine an mGluR1/5 subtype-specific ERK activation and its role in Ca2+ signalling, and (3) determine the specific Ca2+ mechanisms involved in LTP induction at interneurone synapses.

Methods

Western blot analysis

All experiments were done in accordance with the University of Montreal animal care guidelines. Transverse hippocampal slices were obtained from 15- to 23-day-old Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River, St-Laurent, Qc). Animals were deeply anaesthetized with halothane. After decapitation, the brain was rapidly removed into ice-cold, oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (mm): 124 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 2 MgSO4, 2 CaCl2 and 10 glucose (pH = 7.4, 300 mosmol l−1). Slices (400 μm thick) were cut with a McIlwain tissue chopper (The Mickle Laboratory Engineering Co. Ltd, Gomshall, UK) and transferred to a chamber with ice-cold oxygenated ACSF where mini-slices consisting of CA1 region were surgically isolated under a dissection microscope. CA1 slices were collected in slice holding chambers in heated (31°C) oxygenated ACSF and allowed to recover for 1 h. Afterwards slices were pre-treated with the different drugs specified in each experiment for 1 h, stimulated with the group I mGluR agonist (RS)-3,5-DHPG and then transferred to cold ACSF. Each sample containing four to six slices was stored at −80°C until biochemical analysis.

Samples were homogenized in 100 μl of ice-cold homogenization buffer containing 10 mm Tris pH 8, 150 mm NaCl, 10 mm EDTA, 1% Triton, protease inhibitors CLAP (0.0001% Chymostatin, 0.0001% Leupeptine, 0.0001% Antipain and 0.0001% Pepstatin), 200 μm sodium orthovanadate, 200 μm sodium fluoride, and 0.2 mm phenyl-methyl-sulphonylfluoride (PMSF). The homogenate was then centrifuged at 14 000 g for 20 min at 4°C to remove debris. The supernatant was transferred and protein concentration was determined by the bicinchoninic acid method (Pierce) using bovine serum albumin as a standard. Proteins were immediately denatured in a sample buffer containing 62.5 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol and 50 mm dithiothreitol. Equal sample amounts (50 μg lane−1) were subjected to 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Gels were then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for 2 h at a constant voltage. The membrane was stained with Ponceau red briefly to verify the quality of transfer. The membrane was blocked in 5% non-fat milk, 0.25% BSA dissolved in TBS-Tween 20 (TBST) buffer containing the following: 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 15 mm NaCl and 0.1% Tween 20 for 1 h at room temperature. After blocking, the membrane was probed with primary antibodies that recognize dually phosphorylated (Thr202/Tyr204)-ERK1/2 (1/5000, Santa Cruz) overnight at 4°C. After incubation, the membrane was washed three times for 5 min each with TBST. The membrane was then incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody in TBST containing 5% non-fat milk (1/10,000, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was washed again three times for 5 min each with TBST. Immunoreactive bands were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). To determine the total amount of ERK1/2, the membrane was stripped in stripping buffer (0.1 m glycine, pH 2.2, 1% SDS) for 1 h at room temperature, washed and reprobed with anti-ERK1/2 antibodies (1/10,000, Santa Cruz). The rest of the procedure was the same as that for phospho-ERK1/2 antibody.

The anti-phosphorylated-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) and anti-ERK1/2 immunoreactive bands of the same gel were scanned with a desktop scanner and quantified with Quantity One software (Bio-Rad). The optical densities of anti-phospho-ERK1/2 bands were normalized to the optical density of their own anti-ERK1/2 bands and expressed as the percentage increase over the basal condition. Summary data are expressed as mean ±s.e.m. Statistical significance was determined using a two-tailed Student's t test.

Immunocytochemistry

Transverse hippocampal slices (300 μm thick) were collected in slice holding chambers in heated (31°C) oxygenated ACSF, allowed to recover for 1 h, stimulated with (S)-3,5-DHPG (10 μm, 5 min) and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (PB; 3 h, pH 7.4). Afterwards, slices were resectioned (50 μm thick) using a freezing microtome (Leica SM 2000R, Germany) and processed for labelling with rabbit anti-phosphoERK1/2 (1: 200, Cell Signalling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA; 24 h). Sections were subsequently incubated in biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgGs (1: 200) and then in avidin–biotin complex (Elite ABC kit; 1: 100, Vector Laboratories; 1 h). The reaction product was visualized using 0.05% 3′3-diaminobenzidine, 0.2% nickel sulphate, 0.1 m imidazole and 0.0015% H2O2 in Tris buffer (0.05 m, pH 7.6).

Electrophysiological recordings

After anaesthesia and decapitation, the rat brain was rapidly removed into ice-cold, oxygenated ‘cutting’ solution containing (mm): 250 sucrose, 2 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 7 MgSO4, 0.5 CaCl2 and 10 glucose (pH = 7.4, 320–340 mosmol l−1). Transverse hippocampal slices (300 μm thick) were cut with a Vibratome (Leica VT1000S, Germany), transferred to heated (35°C) oxygenated ACSF containing (mm) 124 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 3 MgSO4, 1 CaCl2 and 10 glucose, and allowed to cool down to room temperature in 30 min. Slices were allowed to recover for at least 1 h before experiments.

During experiments, slices were perfused continuously (2.5 ml min−1) with ACSF at 31–33°C. CA1 interneurones of stratum oriens/alveus were identified with the aid of an infrared camera (70 Series, DAGE-MTI, MI, USA) mounted on an upright microscope (Axioskop 2FS, Zeiss) equipped with long-range water-immersion objective (40 ×, numerical aperture 0.8). Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were made from somata using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments). Recording pipettes (4–5 MΩ) were filled with a solution containing (mm): 130 CsMeSO3, 5 CsCl, 2 MgCl2, 5 di-sodium phosphocreatine, 10 Hepes, 2 ATPTris, 0.4 GTPTris, and 0.2 Oregon Green-488-BAPTA-1- hexapotassium salt (OGB-1, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) or 0.2 Fluo-4 pentapotassium salt (pH 7.25–7.35, 275–285 mosmol l−1). Cells were voltage clamped at −60 mV. Membrane currents were low-pass filtered at 2 KHz, digitized at 10 KHz and stored on a microcomputer using a data acquisition board (Digidata1322A, Axon Instruments) and pCLAMP 8 software (Axon Instruments).

Direct activation of postsynaptic group I mGluRs was achieved by local micropressure application of (S)-3,5-DHPG (100 μm; 35–70 kPa, 20–100 ms) via a glass pipette (tip diameter 2–3 μm) connected to a pressure application system (PicoSpritzer II, Parker Instrumentation, Fairfield, NJ, USA) and positioned ∼10 μm above the dye-filled dendrite. In order to achieve the precise positioning of the puff-pipette, the tip was marked with concentrated water-insoluble dye DiI (Molecular Probes). DHPG applications were repeated at constant intervals of 1–2 min and typically reproducible postsynaptic responses were elicited by four DHPG applications.

Ca2+ imaging of interneurone dendrites

After obtaining the whole-cell configuration, 20–30 min were allowed for intracellular diffusion of the fluorophore. Imaging was performed using a two-photon laser scanning microscope (LSM 510, Zeiss) with a mode-locked Ti:sapphire laser operated at 800 nm wavelength, 76 MHz pulse repeat, < 200 fs pulse width and pumped by a solid state source (Mira 900 and 5 W Verdi argon ion laser, Coherent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Fluorescence was detected through a long-pass filter (cut-off 680 nm) in non-descanned detection mode and images were acquired using the LSM 510 software (Zeiss). Fluorescence signals were collected by scanning a line along the dendrite of interest (total length: ∼5–20 μm). Fluorescence transients were measured at 20–150 μm from the soma. The image focus of the line was carefully checked and occasionally adjusted for possible drift. Electrophysiological recordings and Ca2+ imaging were typically stable for ∼1 h.

LTP induction

Synaptic responses were evoked with constant current pulses (50 μs) via an ACSF-filled bipolar theta-glass electrode positioned ∼100 μm from the cell body in stratum oriens. Putative single-fibre EPSCs were evoked at 0.5 Hz using minimal stimulation, as previously described (Perez et al. 2001; Lapointe et al. 2004). LTP was induced by three episodes (given at 30 s intervals) of theta-burst stimulation (TBS; five bursts at 200 ms intervals (5 Hz), each burst consisting of four pulses at 100 Hz), paired with five 60 ms depolarizing steps to −20 mV (Fig. 9). EPSCs were recorded for at least 30 min after the LTP induction protocol.

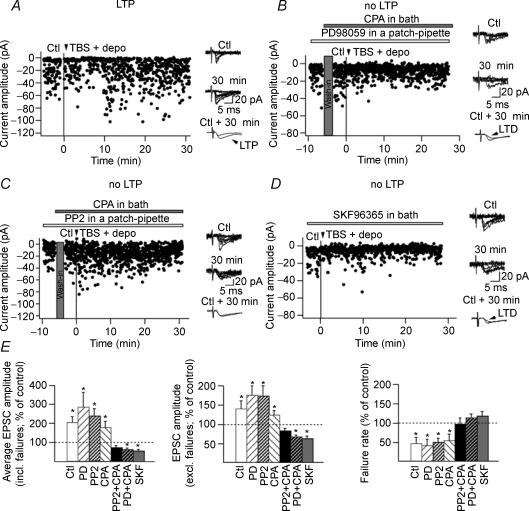

Figure 9. Src/ERK cascade, TRP channels and intracellular Ca2+ release are necessary for LTP induction in interneurones.

A, graph of EPSC amplitude from a representative interneurone showing LTP after TBS paired with depolarization (TBS + depo) delivered at the time indicated by the black arrowhead and vertical line. Ten consecutive traces in control (Ctl) and 30 min after pairing (30 min) are shown superimposed at right. Superimposed average EPSCs including failures (n = 90 responses each; bottom traces) from control and 30 min after pairing show LTP. B, graph of EPSC amplitude from a representative interneurone showing the absence of LTP when the pairing protocol was given in the presence of the inhibitor of MEK (PD98059) and after intracellular Ca2+ store depletion with CPA. A long-term depression (LTD) was uncovered in these conditions. C, representative results from another interneurone showing the absence of LTP when the pairing protocol was given in the presence of the inhibitor of Src (PP2) and after depletion of internal Ca2+ stores (CPA). D, representative results from an interneurone showing that LTP was prevented when the pairing protocol was given in the presence of the inhibitor of TRP channels (SKF96365). In these conditions also, LTD was uncovered. E, summary bar graphs for all cells showing LTP in control conditions (Ctl) which was expressed as a significant increase in the amplitude of average EPSCs (including failures; left), significant increase in EPSC amplitude (excluding failures; middle), and a significant decrease in failure rate (right) at 30 min after induction. LTP was blocked in the presence of the inhibitor of Src PP2, or in the presence of the inhibitor of MEK PD98059, when intracellular Ca2+ stores were depleted (CPA), or in the presence of the TRP channels antagonist SKF96365. LTD was unmasked in PD98059 and CPA, or in SKF96365.

Pharmacology

DHPG-evoked postsynaptic currents and associated Ca2+ transients were examined in the presence of tetrodotoxin (TTX) (0.5 μm) and bicuculline (Bic; 10 μm; Sigma). All compounds were prepared as stock solutions, frozen at −20°C, and diluted on the day of experiment. In some experiments the mGluR1α antagonist LY367385 (100 μm), the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP hydrochloride (25 μm, RBI, Natick, MA, USA), the SERCA antagonist CPA (30 μm), the non-selective TRP channel antagonist SKF96365 hydrochloride (30 μm) (Tocris, Ellisville, MO, USA), the MEK inhibitor PD98059 (50 μm) (Sigma), the Src tyrosine kinase inhibitors PP2 (50 μm) or SU6656 (0.5–1 μm) (Calbiochem) were added to the extracellular solution.

Data analysis

Ca2+ measurements and electrophysiological recordings were analysed using the LSM 510 software, Clampfit 9.0 (Axon Instruments) and IgorPro (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, USA). For analysis of Ca2+ transients, the fluorescence background was subtracted from the fluorescence intensity averaged over the line. Changes in fluorescence were calculated relative to the baseline (from 1 s prior to stimulation) and expressed as %ΔF/F= ((F – Frest)/Frest) × 100. The relation between the amplitude of the Ca2+ signal and the amplitude of the associated current was described using a linear regression. The latency of the current and Ca2+ signal was determined as the time from the DHPG application to the response onset. The time-to-peak of responses was calculated as the time from the DHPG application to the peak amplitude of responses (Figs 1C1 and C2, and 2E). Decay kinetics of membrane currents were fitted using single exponential fitting algorithms of IgorPro. The half-width of Ca2+ transients was measured to assess the kinetics of Ca2+ responses. Summary data are expressed as mean ±s.e.m. Statistical significance between two groups was determined using a two-tailed Student's t test. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by appropriate post hoc tests (Student-Newman-Keuls or Tukey-Kramer) was used for multiple comparisons.

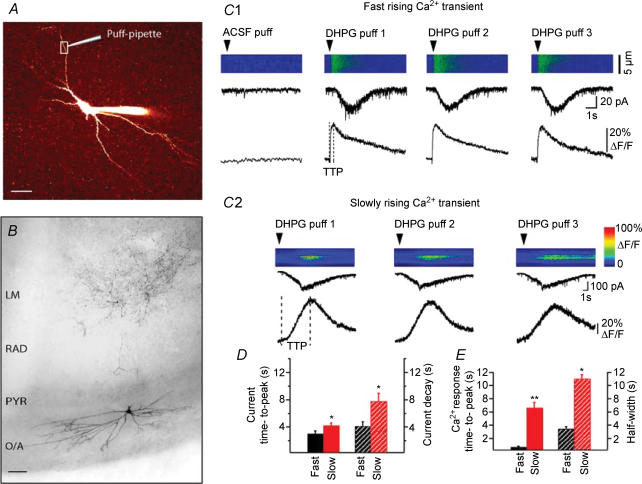

Figure 1. Two distinct types of dendritic Ca2+ signals and postsynaptic currents evoked by local application of DHPG in hippocampal CA1 oriens/alveus (O/A) interneurones.

A, two-photon image (Z-stack) of 120 optical sections taken at 0.5 μm intervals of an O/A interneurone filled with Oregon Green BAPTA-1 (OGB-1). The position of the DHPG-containing puff-pipette is indicated near the dendritic region of interest denoted by the box. Scale bar, 20 μm. B, reconstruction of a biocytin-filled interneurone. Scale bar, 50 μm. C, line scan images obtained from dendritic regions of different O/A interneurones illustrating the two types of Ca2+ responses elicited by three consecutive DHPG puffs (arrowhead): fast rising (C1) and slowly rising (C2) Ca2+ transients. Traces below are corresponding dendritic Ca2+ transients (bottom) and associated postsynaptic currents recorded from the soma (top). Dotted lines indicate the time to peak of distinct Ca2+ responses. D and E, bar graphs of the mean time to peak and decay times of current (D) and the mean time to peak and half-width of Ca2+ transients (E) for the two response types for all cells (**P < 0.005, *P < 0.05; fast, n = 29; slow, n = 36).

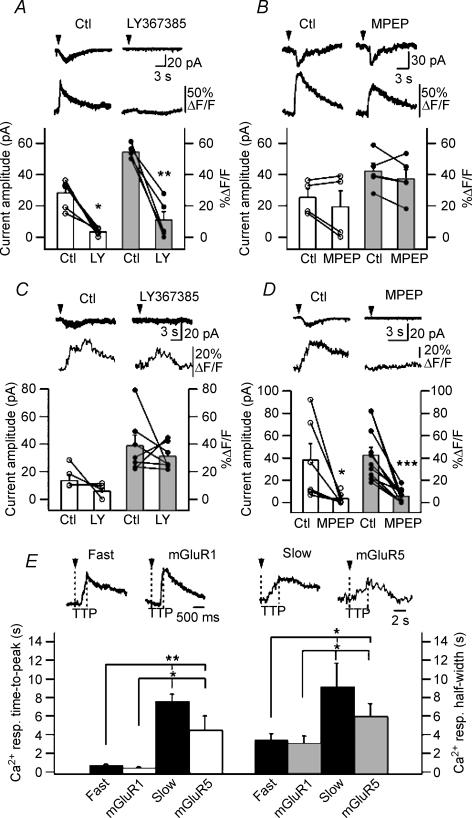

Figure 2. mGluR1α mediates fast rising Ca2+ signals and postsynaptic currents whereas mGluR5 mediates slowly rising Ca2+ transients and currents.

A and B, top, representative examples of fast rising Ca2+ transients and currents evoked by DHPG in control (Ctl) and in the presence of the mGluR1α antagonist LY367385 (A) and mGluR5 antagonist MPEP (B). A and B, bottom, summary plots for all cells showing that fast rising Ca2+ transients (grey bars) and associated membrane currents (white bars) evoked by DHPG were significantly reduced by the mGluR1α antagonist LY367385 (**P < 0.005, *P < 0.05, n = 6) but not by the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP (P > 0.05, n = 4). C and D, top, representative examples of slowly rising Ca2+ signals and associated currents evoked by DHPG in control, in the presence of the mGluR1α antagonist LY367385 (C) and the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP (D). C and D, bottom, summary plots for all cells showing that slowly rising Ca2+ transients (grey bars) and associated membrane currents (white bars) were significantly blocked by MPEP (***P < 0.001, *P < 0.05, current: n = 6; Ca2+ transient: n = 9) but not by LY367385 (P > 0.05, current: n = 4; Ca2+ transient: n = 6). E, top, comparison of representative fast rising Ca2+ transients with those mediated by mGluR1 (recorded in the presence of MPEP) (left), and of slowly rising Ca2+ responses with those mediated by mGluR5 (recorded in the presence of LY367385) (right). Dotted lines indicate the time to peak of Ca2+ responses. E, bottom, summary bar graph showing the mean time to peak and half-width of fast and slowly rising Ca2+ transients and of pharmacologically isolated mGluR1 and mGluR5 Ca2+ responses (**P < 0.005, *P < 0.05, ANOVA).

Histology

Biocytin (0.15–0.2%, Sigma) was routinely added to the internal patch solution to allow cell labelling and reconstruction. Visualization of biocytin was performed as described elsewhere (Perez et al. 2001). Light microscopic reconstructions were carried out using an Eclipse E600W microscope (Nikon, Japan) equipped with a digital camera (Retiga 1300, QImaging, Burnaby, BC, Canada).

Results

mGluR1α- and mGluR5-specific Ca2+ signalling in O/A interneurones

We first investigated Ca2+ mechanisms linked specifically to mGluR1 and mGluR5 activation in O/A interneurones. Interneurones were recorded in whole-cell voltage-clamp mode and filled with fluorescent Ca2+ indicators Oregon Green BAPTA-1 (OGB-1; Fig. 1A) or Fluo-4. Biocytin labelling confirmed that cells recorded were CA1 interneurones with their soma located in stratum oriens near the alveus and horizontally running dendrites (n = 22). In seven of these cells, the axonal arborization was visualized and projected to stratum lacunosum-moleculare (Fig. 1B). Micropressure application of the group I mGluR agonist (S)-3,5-DHPG (100 μm) via a puff-pipette positioned ∼10 μm near the dendrite of interest evoked local dendritic Ca2+ transients which were imaged with the two-photon laser-scanning microscope in the line-scanning mode while membrane currents were recorded in the soma (Fig. 1C). Control local application of ACSF did not evoke any change in dendritic fluorescence or membrane current (Fig. 1C1), whereas consecutive DHPG applications elicited reproducible dendritic responses (Fig. 1C1 and C2). DHPG-evoked Ca2+ responses differed significantly between different cells or different dendritic microdomains of the same interneurone (Fig. 1C1 and C2). Based on the time required to reach the response peak, two distinct types of dendritic Ca2+ transients were clearly detected: fast rising (with a time to peak up to 2 s; mean ±s.e.m., 0.7 ± 0.1 s; n = 29; Fig. 1C1 and E, black) and slowly rising (with a time to peak exceeding 2 s; mean ±s.e.m., 6.6 ± 0.5 s; P < 0.01; n = 30; Fig. 1C2 and E, red) Ca2+ responses. In addition, fast rising Ca2+ signals demonstrated large amplitude (peak Ca2+ signal: 43.6 ± 4.1%ΔF/F, n = 29) and relatively fast time course (Ca2+ response half-width: 3.4 ± 0.7 s; n = 29; Fig. 1E, black) and were associated with large and fast membrane currents (current amplitude: −54.9 ± 12.2 pA; time to peak: 3.0 ± 0.4 s, n = 20; decay: 4.0 ± 0.3 s, n = 17; Fig. 1D, black). The slowly rising Ca2+ signals showed significantly smaller amplitude (peak Ca2+ signal: 29.3 ± 2.9%ΔF/F; P < 0.05, n = 30) and slower time course (Ca2+ response half-width: 10.9 ± 1.5 s; P < 0.01; n = 19; Fig. 1E, red). The majority of slowly rising Ca2+ transients were associated with small slow currents (current amplitude: −20.4 ± 3.7 pA; time to peak: 4.3 ± 0.3 s; decay: 7.7 ± 0.8 s, n = 17; Fig. 1D, red). However, many cells (14 of 30) demonstrated slowly rising Ca2+ signals without detectable membrane currents. We thus examined the relationship between DHPG-evoked currents and both types of Ca2+ signals. We found that the onset of fast rising Ca2+ transients always preceded that of associated currents (Ca2+ transient latency: 0.3 ± 0.05 s; current latency: 1.0 ± 0.2 s). In fact, currents usually appeared when fast rising Ca2+ transients had reached their peak (Ca2+ transient time to peak: 0.7 ± 0.1 s). Also, the amplitude of fast Ca2+ transients was significantly correlated with the amplitude of associated currents (r2= 0.77, n = 10, P < 0.05). These data suggest that currents associated with fast rising Ca2+ transients were dependent on [Ca2+]i elevation. By contrast, the latency of slowly rising Ca2+ signals (1.8 ± 0.3 s) was similar to that of associated currents (1.4 ± 0.2 s). Moreover, the amplitude of slow Ca2+ signals was not correlated with the amplitude of currents (r2 = 0.30, n = 12, P > 0.05). These data indicate that different mechanisms may be involved in the generation of currents associated with fast and slowly rising Ca2+ signals.

We next determined if the two distinct DHPG responses were mediated by different subtypes of the group I mGluRs, using the selective antagonist of mGluR1α, LY367385, and of mGluR5, MPEP (Fig. 2). Fast rising Ca2+ transients and associated currents were significantly inhibited by LY367385 (current amplitude: to 2 ± 0.3% of control, P < 0.05; peak Ca2+ signal: to 17.2 ± 6.1% of control, P < 0.005; n = 6; Fig. 2A) but not by MPEP (P > 0.05; n = 4; Fig. 2B). In contrast, slow rising Ca2+ responses and associated currents were significantly reduced by MPEP (current amplitude: to 4.7 ± 2.9% of control, P < 0.05; n = 6; peak Ca2+ signal: to 17.9 ± 5.5% of control, P < 0.001, n = 9; Fig. 2D) but not by LY367385 (P > 0.05; Fig. 2C). Several cells (6 of 29) demonstrated Ca2+ responses of mixed kinetics with a fast rising phase but a slow plateau-like time course suggesting that fast and slow rising Ca2+ transients were not mutually exclusive. To test if both mGluR1α and mGluR5 could concurrently contribute to Ca2+ responses in some dendritic microdomains, we measured the area under the curve of Ca2+ responses and examined its sensitivity to mGluR1α and mGluR5 antagonists. Again, fast rising Ca2+ signals (including slowly decaying plateau-like responses) were significantly inhibited by LY367385 (Ca2+ response area under the curve: to 13.4 ± 7.8% of control, P < 0.05, n = 6) but not by MPEP (Ca2+ response area under the curve: to 66.3 ± 11.7% of control, P > 0.05, n = 4) suggesting that both fast rising and slowly decaying plateau-like components of fast rising Ca2+ responses are mediated by mGluR1α. To further confirm that the fast rising Ca2+ response is a hallmark of mGluR1α activation whereas slowly rising Ca2+ signals primarily result from the activation of mGluR5, we compared the kinetics of pharmacologically isolated mGluR1α and mGluR5 Ca2+ responses (Fig. 2E). We found that dendritic Ca2+ signals evoked by DHPG in the presence of MPEP, and thus mediated by mGluR1α, showed significantly faster kinetics than those recorded in the presence of LY367385 and mediated by mGluR5 (Fig. 2E). Moreover, the kinetics of mGluR1α-mediated Ca2+ signals was similar to that of fast rising Ca2+ responses whereas the kinetics of mGluR5 Ca2+ transients was in the same range as the kinetics of slow rising Ca2+ signals (Fig. 2E). These data clearly demonstrate differential mGluR1α and mGluR5 dendritic Ca2+ signals and associated currents in O/A interneurones: fast rising and large responses mediated via mGluR1αversus slowly rising and small signals via mGluR5.

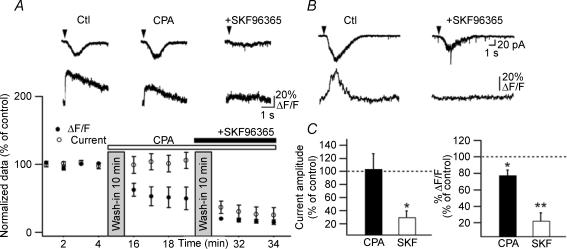

Distinct mechanisms of fast rising mGluR1α- and slowly rising mGluR5-mediated Ca2+ signals and postsynaptic currents

Having found that mGluR1/5 activation produces distinct Ca2+ signals within different dendritic microdomains of interneurones, we investigated the mechanisms of mGluR1/5 subtype-specific Ca2+ signalling. mGluR1/5 are coupled to G-protein-dependent pathway producing intracellular Ca2+ release (Pin & Duvoisin, 1995). In addition, mGluR1 is linked to store-operated (SOC) or TRP channels in midbrain dopamine neurones (Tozzi et al. 2003) and with a TRPC1 channel in cerebellar Purkinje cells (Kim et al. 2003) suggesting that its activation may result in Ca2+ entry. Thus, we next determined the role of intracellular Ca2+ release and Ca2+ entry via TRP channels in fast rising mGluR1α-mediated Ca2+ transients and associated currents, using the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) pump antagonist cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) (30 μm) and the non-selective TRP channel antagonist SKF96365 (30 μm) (Fig. 3). Depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores with CPA produced an increase in basal dendritic fluorescence (data not shown) and resulted in a slight reduction of fast rising Ca2+ signals (peak Ca2+ signal: to 77.4 ± 6.4% of control; P < 0.05; n = 6) but did not significantly affect the associated membrane currents (Fig. 3A and C). The effects of CPA on fast rising Ca2+ signals were variable from cell to cell (range: reduction to 38% and 82% of control). SKF96365 inhibited the DHPG-evoked fast rising Ca2+ transients and associated currents to a large extent (current amplitude: to 29.9 ± 9.3% of control; P < 0.05; peak Ca2+ signal: to 22.3 ± 9.5% of control; P < 0.05; n = 7; Fig. 3B and C) and blocked them completely in 3 out of 7 cells. Moreover, the residual Ca2+ transients and membrane currents observed in CPA were blocked by SKF96365 (n = 4; Fig. 3A) and, thus mediated by TRP channel activation. These results indicate that Ca2+ entry via TRP channels mediates the major component of mGluR1α fast rising Ca2+ transients whereas intracellular Ca2+ release mediates a minor part of the Ca2+ signal.

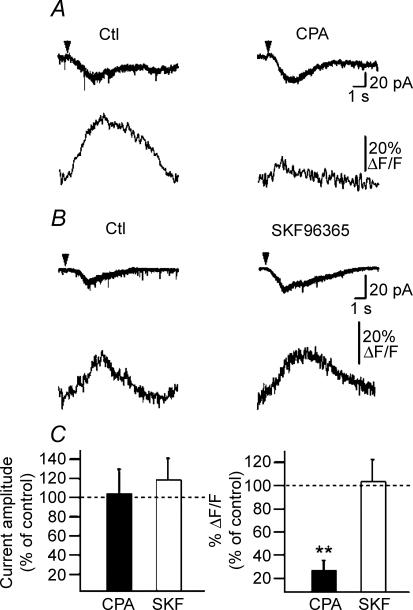

Figure 3. Differential contributions of intracellular Ca2+ release and Ca2+ entry via TRP channels in fast rising Ca2+ signals and postsynaptic currents.

A, top, representative currents and Ca2+ transients in control (Ctl), after the internal Ca2+ stores depletion (CPA) and after subsequent inhibition of Ca2+ entry via TRP channels (SKF96365). A, bottom, summary plot of normalized current amplitude and peak Ca2+ transients illustrating that CPA did not affect currents but depressed Ca2+ transients and that a subsequent application of SKF96365 successfully inhibited both currents and Ca2+ signals. B, representative traces of fast rising Ca2+ transients and associated membrane currents in control (Ctl) and after inhibition of Ca2+ entry via TRP channels (SKF96365). C, bar graphs for all cells showing that inhibition of TRP channels (SKF96365) blocked most of fast rising Ca2+ signals (right) and currents (left) whereas depletion of internal stores (CPA) produced a small reduction only of Ca2+ signals (CPA: n = 5; SKF96365: n = 6; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005).

We then examined the Ca2+ mechanisms involved in slowly rising mGluR5-mediated responses. In contrast to fast rising mGluR1α responses, the slowly rising Ca2+ transients evoked by DHPG were almost completely blocked by depletion of internal stores by CPA (P < 0.01; n = 6; Fig. 4A and C) and were not affected by preventing Ca2+ entry via TRP channels by SKF96365 (P > 0.05; n = 7; Fig. 4B and C). Membrane currents associated with slowly rising Ca2+ signals were not sensitive to either CPA or SKF96365 (P > 0.05; Fig. 4A–C), indicating that these currents were independent of TRP channels and release of Ca2+ from internal stores. Thus, our results reveal that mGluR5-mediated slowly rising Ca2+ transients arise from intracellular Ca2+ release.

Figure 4. Intracellular Ca2+ release contributes to slowly rising Ca2+ transients.

A, representative traces of slowly rising Ca2+ transients and associated membrane currents in control (Ctl) and after depletion of internal Ca2+ stores (CPA). B, representative currents and slowly rising Ca2+ transients in control (Ctl) and after inhibition of Ca2+ entry via TRP channels (SKF96365). C, right, bar graphs for all cells showing that slowly rising Ca2+ transients were significantly blocked by the inhibition of intracellular Ca2+ release (CPA: n = 6; **P < 0.005) and were not affected by inhibition of TRP channels (SKF96365: n = 7). C, left, summary bar graphs indicating that associated currents were not affected by CPA or SKF96365.

mGluR1α -selective activation of Src-dependent ERK1/2 phosphorylation in CA1 O/A interneurones

We next investigated the intracellular signalling mechanisms involved in mGluR1/5 subtype-specific Ca2+ signalling. Group I mGluRs are known to signal to the ERK/MAPK cascade (Peavy & Conn, 1998; Ferraguti et al. 1999; Thandi et al. 2002) and we studied the activation of the ERK/MAPK cascade by mGluR1 and mGluR5 in CA1 hippocampus. We examined with Western blot analysis whether mGluR1/5 activation with the selective agonist (RS)-3,5-DHPG elicits ERK1/2 phosphorylation in rat hippocampal CA1 mini-slices. Following stimulation with DHPG (10 μm), we found a time-dependent increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation, as detected using phosphospecific antibodies (Fig. 5A). ERK phosphorylation was induced rapidly, with a maximum at 2 min of DHPG treatment (165.2 ± 16.6% of basal; n = 5; P < 0.05). This increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation was transient, persisted for 5 min (148.5 ± 6.8%; n = 6; P < 0.01) and was not detected at 10–20 min. To determine the mGluR subtype linked specifically to ERK activation, we assessed DHPG-induced ERK phosphorylation in CA1 mini-slices pretreated with the mGluR1α antagonist LY367385 (100 μm) or the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP (30 μm; Fig. 5B). DHPG-induced increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation (DHPG: 138.5 ± 2.4%) was prevented by the mGluR1α antagonist (DHPG + LY: 105.5 ± 11.3%; n = 4) but not by the mGluR5 blocker (DHPG + MPEP: 136.7 ± 10.0%; n = 4). These results indicate that the rapid and transient activation of ERK in the CA1 region is mediated selectively via mGluR1α and not mGluR5. In hippocampal CA1 area, mGluR1α is highly expressed in O/A interneurones (Baude et al. 1993). Thus, we investigated if the mGluR1α-mediated rapid increase in ERK phosphorylation in the CA1 hippocampal area also occurred in O/A interneurones. Rat hippocampal slices were stimulated with DHPG (10 μm, 5 min) and processed for immunocytochemical detection with phospho-ERK1/2 antibodies (Fig. 5C). In basal conditions, phospho-ERK1/2 immunoreactivity was below the detection level in neurones of CA1 area (n = 8 slices). After DHPG treatment, phospho-ERK1/2 immunostaining was revealed in interneurones somata primarily in stratum oriens-alveus and occasionally in neurones of stratum pyramidale (n = 11 slices; Fig. 5Cc and d). In order to rule out network effects mediated by DHPG activation of group I mGluRs on pyramidal cells, we examined DHPG-induced phospho-ERK1/2 immunoreactivity in slices in the presence of TTX (0.5 μm; Fig. 5D). After 5 min of DHPG treatment in the presence of TTX, phospho-ERK1/2 immunostaining was similarly found in O/A interneurones (n = 4 slices; Fig. 5Db). These data show that the transient and rapid mGluR1α-mediated ERK phosphorylation in CA1 area also occurs in interneurones and more specifically in O/A cells.

Figure 5. mGluR1α, but not mGluR5, is linked to ERK1/2 phosphorylation in O/A interneurones.

A, representative Western blots of extracts of hippocampal CA1 mini-slices treated with DHPG (10 μm) for the indicated times, showing DHPG-induced time-dependent increase in ERK phosphorylation. Top, anti-phospho-ERK1/2 blot; bottom, anti-total-ERK1/2 blot. In each panel, the top band is p44 MAPK (ERK1) and the bottom band is p42 MAPK (ERK2). Bar graph shows summary data indicating the time course of DHPG-induced increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, n = 6); the ratio of phospho-ERK1/2 (pERK1/2) to total-ERK1/2 immunoreactivity was normalized to the basal value. B, representative Western blots of mini-slices pretreated (+) or not (−) with mGluR1α antagonist LY367385 (100 μm) or mGluR5 antagonist MPEP (30 μm) and stimulated with DHPG (10 μm, 5 min). Bar graph shows summary data illustrating that DHPG-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation (***P < 0.001) was blocked by LY367385 and not by MPEP (*P < 0.05, n = 4). C, phospho-ERK1/2 immunocytochemical labelling in different hippocampal slices in control conditions (Ca and Cb) and after DHPG treatment (Cc and Cd). Boxed regions shown at higher magnification (Cb and Cd) demonstrate DHPG-induced prevalent pERK1/2 immunolabelling of O/A interneurones. D, phospho-ERK1/2 immunolabelling in different hippocampal slices in basal conditions (Da) and after DHPG treatment (Db) in the presence of TTX (0.5 μm). Scale bars in C, 100 μm (left panels) and 50 μm (right panels); in D, 50 μm.

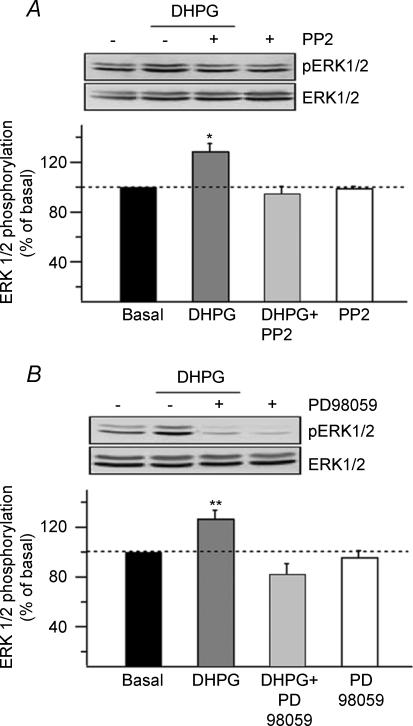

We next examined the signalling cascade linking mGluR1α and ERK phosphorylation. The Src-family tyrosine kinases have been shown to be important in mediating ERK activation via mGluR1/5 (Thandi et al. 2002; Zhao et al. 2004). To investigate whether mGluR1α-mediated ERK phosphorylation in CA1 hippocampus required the activation of the Src-family kinases, we used the cell-permeable Src-family kinase inhibitor PP2 (50 μm; Fig. 6A). Hippocampal CA1 mini-slices pretreated with PP2 did not show significant increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation following DHPG stimulation for 5 min (DHPG: 129.0 ± 5.6%; DHPG + PP2: 94.8 ± 5.5%; n = 5). Treatment with PP2 alone did not affect basal ERK1/2 phosphorylation, indicating that the Src-family kinase inhibitor selectively blocked the DHPG response. It is well established that ERK1/2 are phosphorylated on tyrosine and threonine residues by the mitogen extracellular regulating kinase (MEK) (Grewal et al. 1999). To verify that ERK1/2 phosphorylation in CA1 hippocampus occurred via classical MEK activation, we used the MEK inhibitor PD98059 (10 μm; Fig. 6B). DHPG stimulation of CA1 mini-slices pretreated with PD98059 did not evoke a significant increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation (DHPG: 127.0 ± 6.3%; DHPG + PD: 82.4 ± 8.2%; n = 5). Treatment with PD98059 alone did not significantly affect basal ERK1/2 phosphorylation. These data clearly indicate that rapid and transient ERK1/2 phosphorylation induced by mGluR1α activation in CA1 hippocampus involves Src and MEK activation.

Figure 6. mGluR1α-mediated ERK1/2 phosphorylation involves Src and MEK activation.

A and B, representative Western blots of hippocampal CA1 mini-slices pretreated (+) or not (−) with the cell-permeable Src tyrosine kinase inhibitor, PP2 (50 μm, 1 h; A) or the MEK inhibitor, PD098059 (10 μm, 1 h; B) before stimulation with DHPG. Bar graphs with summary data showing that DHPG-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation was blocked by PP2 and PD98059. Neither inhibitor affected basal ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Their relative effect on DHPG-induced phosphorylation indicates an involvement of the non-receptor tyrosine kinase Src and MEK in the mGluR1α/ERK signalling pathway in CA1 hippocampus (**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, n = 5).

Differential involvement of Src/ERK cascade in fast and slowly rising Ca2+ signalling in O/A interneurones

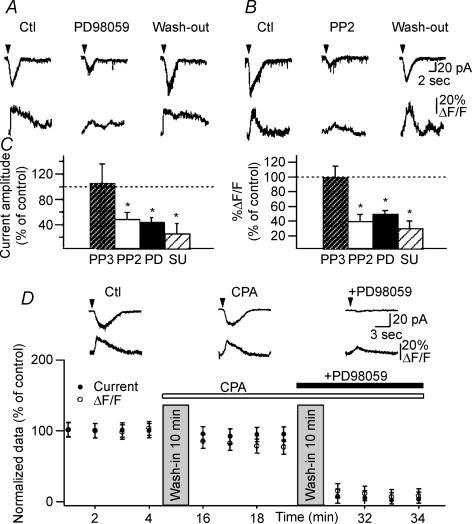

Having found an mGluR1α-specific activation of the Src/ERK cascade in CA1 hippocampus, we next examined whether this cascade could be involved in the regulation of mGluR1/5-mediated Ca2+ signals and currents in O/A interneurones. Fast rising Ca2+ transients and associated currents evoked by DHPG were inhibited by the MEK inhibitor PD98059 (P < 0.05; n = 5; Fig. 7A and C), as well as by the Src-family kinase inhibitors PP2 (P < 0.05; n = 4; Fig. 7B and C) and SU6656 (P < 0.05; n = 5; Fig. 7B and C). PP3 (50 μm), an inactive analogue of PP2, did not exert these effects (P > 0.05; n = 4; Fig. 7B and C). The effects of PD98059 and PP2 were reversible and DHPG responses recovered after drug wash-out (n = 3; example in Fig. 7A and B). Since these agents depressed fast rising Ca2+ responses and associated currents (Fig. 7C), our results indicate that Src and MEK activation may be necessary for both mGluR1α-mediated Ca2+ responses and associated currents. Moreover, the residual DHPG-evoked fast rising Ca2+ transients and membrane currents observed in CPA and, thus mediated by TRP channel activation (Fig. 3A), were blocked by PD98059 (n = 3; Fig. 7D). These data indicate that fast rising Ca2+ transients and currents arising from Ca2+ influx via TRP channels, that involve mGluR1α activation, are dependent on activation of the Src/ERK cascade.

Figure 7. Src/ERK cascade is involved in TRP channel-mediated fast rising Ca2+ signals and currents.

A and B, representative currents and Ca2+ transients in control (Ctl), in the presence of the MEK inhibitor PD98059 (A) or the Src tyrosine kinase inhibitor PP2 (B) and after 30 min of drug wash-out (Wash-out). C, bar graphs for all cells showing that the Src inhibitors PP2 and SU6656, as well as the MEK inhibitor PD98059, significantly reduced fast rising Ca2+ transients (right) and currents (left) evoked by DHPG (n = 5, *P < 0.05). In contrast, PP3, an inactive analogue of PP2, did not exert these effects (n = 4; P > 0.05). D, summary data for a subset of cells (n = 3) in which PD98059 was applied in the presence of the inhibitor of intracellular Ca2+ release CPA. Plot of normalized current amplitude and peak Ca2+ transients illustrating that, in the presence of CPA, application of PD98059 significantly inhibited both fast rising Ca2+ signals and currents. Note that for this particular group of cells, CPA effects on fast Ca2+ transients were small due to the small sample size and cell-to-cell variability.

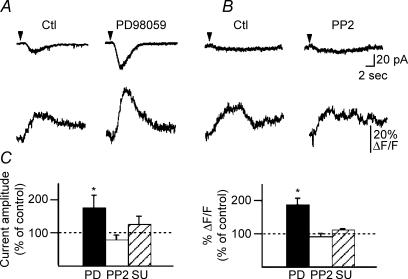

We examined next the role of the Src/ERK cascade in slowly rising Ca2+ responses and currents (Fig. 8A–C). In contrast to fast rising responses, DHPG-evoked slowly rising Ca2+ signals and currents were enhanced by the MEK inhibitor PD98059 (P < 0.05; n = 6; Fig. 8A and C) but not significantly affected by the Src inhibitors PP2 and SU6656 (P > 0.05; n = 5; Fig. 8B and C). These data show that the Src/ERK cascade is not necessary for slowly rising Ca2+ signals and currents that involve mGluR5 activation. Moreover, the enhancement of slowly rising Ca2+ signals and currents by the MEK inhibitor suggests that ERK activation may exert an inhibitory action on certain elements of the mGluR5-dependent transduction pathway. Thus, our results reveal that slowly rising Ca2+ transients, which are mGluR5 mediated, do not require the Src/ERK cascade but may be negatively modulated by ERK. Overall this series of experiments indicate a differential role of the Src/ERK cascade in fast rising versus slowly rising Ca2+ signalling, supporting a differential coupling of mGluR1α and mGluR5 to Src/ERK activation in O/A interneurones.

Figure 8. Slowly rising Ca2+ signals do not require Src/ERK cascade.

A and B, representative traces of slowly rising Ca2+ transients and associated membrane currents in control (Ctl) and in the presence of the MEK inhibitor PD98059 (A) or the Src tyrosine kinase inhibitor PP2 (B). C, bar graphs for all cells showing that slowly rising Ca2+ signals (right) and currents (left) were significantly increased in the presence of the MEK inhibitor (PD98059: n = 6; *P < 0.05) and were not affected by the Src inhibitors (PP2: n = 5, P > 0.05; SU6656: n = 4, P > 0.05).

Src/ERK cascade, TRP channels and intracellular Ca2+ release are necessary for LTP induction in O/A interneurones

Excitatory synapses of O/A interneurones undergo a hebbian form of LTP which is induced by pairing synaptic theta-burst stimulation (TBS) with postsynaptic depolarization and is dependent on mGluR1α and postsynaptic Ca2+ elevation (Perez et al. 2001; Lapointe et al. 2004). Based on our evidence that mGluR1α-mediated dendritic Ca2+ signals depend on Src/ERK activation and Ca2+ entry via TRP channels, as well as intracellular Ca2+ release, we tested the involvement of these Ca2+ signalling pathways in LTP induction. In control conditions, the pairing protocol induced LTP of average EPSCs (including failures; 205.2 ± 21.3% of control) lasting at least 30 min (Fig. 9A) that was associated with a significant decrease in failure rate (47.8 ± 15.1% of control) and an increase in EPSC amplitude (excluding failures; 140.8 ± 20.4% of control; P < 0.05; n = 5; Fig. 9E). We first examined the role of Src/ERK cascade and intracellular Ca2+ release, by applying the pairing protocol during bath application of the MEK inhibitor PD98059, the Src inhibitor PP2 or the SERCA pump inhibitor CPA. Interestingly, blocking ERK, Src or intracellular Ca2+ release alone, did not prevent LTP induction (PD98059: n = 5; PP2: n = 4; CPA: n = 4; Fig. 9E). These data suggest that Ca2+ elevation dependent on Src/ERK activation or intracellular Ca2+ release may be sufficient to support LTP induction in the absence of the other. We then tested if inhibition of both ERK activation and intracellular Ca2+ release would prevent LTP. Inclusion of the ERK inhibitor PD98059 in the whole-cell recording solution and bath application of the SERCA pump inhibitor CPA did not affect basal synaptic transmission in control experiments without pairing (average EPSCs including failures: 114 ± 3.2% of control; failure rate: 105.2 ± 9.2% of control; n = 3). However, this treatment prevented LTP induction in cells receiving the pairing protocol (Fig. 9B and E). Moreover, in the presence of these inhibitors, we found a significant decrease in EPSC amplitude without a change in the failure rate at 30 min post-pairing (n = 5; Fig. 9B and E). Thus, long-term depression (LTD) was uncovered in the presence of PD98059 and CPA. Similarly, intracellular application of the Src inhibitor PP2 (10 μm) combined with bath application of CPA also prevented LTP induction (n = 4; Fig. 9C and E). Finally, we examined if Ca2+ entry via TRP channels was necessary for LTP. TRP channels antagonist SKF96365 did not affect basal synaptic transmission in control experiments without pairing (average EPSCs including failures: 92.6 ± 8.6% of control; failure rate: 104.8 ± 5.7% of control; n = 3). However, treatment with SKF96365 was effective in preventing LTP induction in cells receiving the pairing protocol (Fig. 9D and E). Moreover, in these conditions a long-term depression of EPSCs was also uncovered. This series of experiments clearly indicate that activation of the Src/ERK cascade, Ca2+ entry via TRP channels and intracellular Ca2+ release are required for LTP induction at interneurone excitatory synapses. Thus, overall, our results provide novel evidence that the mGluR1α-, Src- and ERK-dependent Ca2+ signalling cascade via TRP channels and intracellular Ca2+ release control the induction of synaptic plasticity at interneurone excitatory synapses.

Discussion

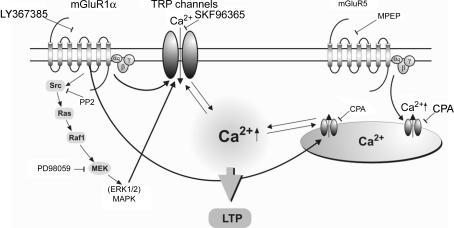

Our results uncovered four main findings regarding mGluR1/5-mediated Ca2+ signalling and LTP in hippocampal interneurones. First, mGluR1α produces fast rising Ca2+ responses via Ca2+ entry through TRP channels with a minor contribution of intracellular release. Second, these mGluR1α-mediated Ca2+ signals are dependent on Src tyrosine kinases and ERK activation. Third, mGluR5 generates slowly rising Ca2+ elevations via release from intracellular stores, independent of Src activation but subject to negative modulation by ERK. Finally, mGluR1α-mediated, Src- and ERK-dependent Ca2+ signalling via TRP channels and intracellular release is necessary for LTP induction in interneurones. These findings demonstrate a novel mGluR1α-specific Ca2+ signalling cascade which underlies long-term synaptic plasticity in hippocampal interneurones (Fig. 10) and identify Src- and ERK-dependent activation of TRP channels as a new mechanism, critical for synaptic plasticity in CNS.

Figure 10. Schematic representation of distinct mGluR1α and mGluR5 Ca2+ signalling pathways and their role in LTP induction in O/A interneurones.

mGluR1 activation is linked to two parallel Ca2+ signalling pathways: one leading to Ca2+ entry via TRP channels and a second producing Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. Src/ERK-dependent Ca2+ entry via TRP channels and intracellular release are necessary for LTP induction. mGluR5 activation causes intracellular Ca2+ release that does not require Src/ERK and TRP channels, and does not appear to be involved in LTP induction.

mGluR1/5 subtype-specific Ca2+ signalling in hippocampal interneurones

In hippocampal pyramidal cells, concurrent activation of mGluR1 and mGluR5 by bath-applied agonists produces mixed Ca2+ responses and membrane currents (Gee et al. 2003; Rae & Irving, 2004), although these receptors may differentially regulate CA1 pyramidal cell function (Mannaioni et al. 2001). In O/A interneurones, local activation of dendritic mGluR1α and mGluR5 revealed receptor subtype-specific Ca2+ signals and membrane currents via distinct mechanisms. mGluR1α Ca2+ transients and associated currents showed relatively fast kinetics and large amplitudes. Similar mGluR1-mediated currents and Ca2+ responses evoked by local application of DHPG are observed in cerebellar Purkinje cells expressing high levels of mGluR1 (Tempia et al. 2001; Kim et al. 2003). In these cells, mGluR1 physically interacts with TRPC1 producing large inward currents (Kim et al. 2003). In O/A interneurones, a major part of mGluR1α Ca2+ transients also resulted from Ca2+ entry via TRP channels with a minor contribution of intracellular release. The latency of associated membrane currents followed that of Ca2+ transients and their amplitude correlated with the magnitude of [Ca2+]i elevation, suggesting an additional activation of Ca2+-dependent non-selective cation current (ICAN) or alternatively of an electrogenic Na+−Ca2+ exchange mechanism. Indeed, ICAN is linked to group I mGluR activation in CA1 pyramidal cells (Congar et al. 1997; Rae & Irving, 2004) and O/A interneurones (McBain et al. 1994). Since fast rising Ca2+ transients in O/A interneurons involved TRP channels, associated currents which follow these Ca2+ transients may be activated by the increase in [Ca2+]i and dependent on TRP channel activation, consistent with data in many systems (Gee et al. 2003; Kim et al. 2003; Tozzi et al. 2003). Cell-type specific mGluR1α/TRP interactions may therefore underlie the fast kinetics and large amplitude of mGluR1α Ca2+ responses and their associated currents.

Multiple mechanisms can activate TRP channels, including receptor activation or internal store depletion (Parekh & Putney, 2005; Ramsey et al. 2006). In addition, recent evidence demonstrates a possible channel regulation via phosphorylation by protein kinases A, C and G (Venkatachalam et al. 2003) or the Src-family kinases (Hisatsune et al. 2004; Odell et al. 2005). Our data show that Src/ERK activation is necessary for fast rising mGluR1α/TRP Ca2+ signals and currents, providing novel functional evidence for receptor-mediated TRP channel Ca2+ signalling dependent on Src/ERK in hippocampus. Interestingly, Src-dependent mGluR1-mediated synaptic currents with similar fast kinetics (∼500 ms rise time) have been reported in CA3 pyramidal cells (Heuss et al. 1999). The precise role of Src/ERK in such rapid signal transduction is presently unclear. Src/ERK activation may directly mediate the mGluR1 responses or phosphorylation of TRP channels (or another element of the transduction cascade) by these kinases may be necessary in order for TRP channels to open or to be coupled to the transduction mechanism. This remains, however, to be determined. The absence of selective antagonists for TRP channel subtypes prevented identification of which TRP channel was involved in mGluR1α and ERK-dependent signalling in interneurones. TRPC1 is functionally associated with mGluR1 in Purkinje cells (Kim et al. 2003) and has multiple potential ERK phosphorylation sites on the intracellular N-terminal. Thus, TRPC1 could be involved in fast mGluR1α Ca2+ signals in interneurones. In any case, our results suggest that TRP channels, in addition to K+ channels (Yuan et al. 2002), may act as ERK effectors in neurones. This specific ERK–TRP interaction and its role in interneurone LTP remain to be tested in future studies.

A component of mGluR1α Ca2+ transients resulted from release from intracellular stores, probably via ryanodine-sensitive stores (Woodhall et al. 1999). These intracellular stores are activated by intracellular Ca2+ rises (i.e. Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR)) (Meldolesi, 2002) and may be regulated by influx via voltage- and ligand-gated Ca2+-permeable channels. Voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) may be activated following TRP channel-mediated depolarization and, thus may contribute partly to the rise in intracellular Ca2+. Therefore, mGluR1α activation of Ca2+ release from ryanodine stores by synaptic activity, and during LTP induction, may require activation of voltage/ligand-gated Ca2+ channels. Interestingly, blocking TRP channels completely abolished mGluR1α Ca2+ signals in 3 out of 7 cells, suggesting that in voltage-clamped interneurones where activation of VGCCs is largely prevented, mGluR1α Ca2+ release may depend on the activation of TRP channels.

In contrast, mGluR5 Ca2+ signals were smaller and slower, and mediated by release from intracellular stores. Since IP3 receptors appear absent in O/A interneurones (Fotuhi et al. 1993), ryanodine-sensitive stores are also likely to be involved in these responses (Woodhall et al. 1999). The slow kinetics of mGluR5 Ca2+ elevations and associated currents may result from a lack of TRP channel component in these responses. Thus mGluR5 activation may provide longer-lasting Ca2+ signals in specific cellular compartments. Our results with blocking intracellular release indicate that such small and slow Ca2+ signals are not sufficient to induce LTP. However, under certain conditions, e.g. during blockade of ERK activation, enhanced mGluR5-mediated intracellular Ca2+ release may potentiate TRP channel activation and lead to LTP induction. Moreover, mGluR5-specific Ca2+ signalling may be relevant for excitotoxicity. Low level, but persistent, intracellular Ca2+ release has been proposed to induce apoptosis through localized calpain and caspase-12 activation (Yuan et al. 2003). This mechanism could be important for the mGluR1/5-dependent vulnerability of O/A interneurones (Renaud et al. 2002) in experimental models of temporal lobe epilepsy (Morin et al. 1998).

mGluR1α activation of Src/ERK cascade

ERK/MAPK are implicated in many neuronal signalling pathways, including cell survival and apoptosis (Bonni et al. 1999), long-term changes in synaptic efficacy (English & Sweatt, 1996), and regulation of gene expression and protein synthesis (Lin et al. 1994). ERK cascade is activated by a number of receptors and protein kinases (Sweatt, 2004), including mGluR1/5 (Peavy & Conn, 1998; Ferraguti et al. 1999; Thandi et al. 2002; Zhao et al. 2004). Our findings of rapid ERK phosphorylation in interneurones (maximum at 2 min) is in contrast to its slower activation in hippocampal pyramidal cells (maximum at 30 min; Berkeley & Levey, 2003) and is indicative of distinct functional roles for ERK in interneurones and pyramidal cells. Our work suggests that ERK activation is necessary for receptor-activated Ca2+ signalling in interneurones, whereas in pyramidal cells it may produce long-term changes involving gene expression and protein synthesis (Kelleher et al. 2004).

Our evidence that ERK1/2 phosphorylation required the Src family tyrosine kinases is consistent with previous data showing Src-dependent ERK activation by G-protein coupled receptors (Luttrell et al. 1999). For instance, the β3-adrenoceptor binds c-Src directly via proline-rich (PXXP) motifs in the third intracellular loop and C-terminus of the receptor (Cao et al. 2000), leading to ERK activation. mGluR1α and mGluR5 possess proline-rich regions (including multiple PXXP motifs) within their long C-terminal domains, suggesting that c-Src may interact via these regions (Hermans & Challiss, 2001). Indeed, both mGluR1α and mGluR5 are linked via Src to ERK1/2 activation in heterologous system (Thandi et al. 2002) and CA3 pyramidal cells (Zhao et al. 2004). However, in O/A interneurones, our data show that, within the time frame examined (20 min), only mGluR1α interacts with Src leading to ERK activation. This mGluR1/5 difference may reflect specific properties of receptor–protein interactions in interneurones. Alternatively, the extra-synaptic localization of mGluR5 may limit its interaction with Src which is localized with components of postsynaptic densities (Atsumi et al. 1993). Another mechanism for a specific mGluR1α–Src interaction is an arrestin-like adaptor protein (Cao et al. 2000). Resolving the molecular mechanism of coupling of mGluR1α and Src tyrosine kinase in hippocampal interneurones will be an important future task.

If mGluR1α-mediated fast rising Ca2+ responses and currents are directly mediated via ERK1/2 activation, this would require very rapid effects of phosphorylation (peak at ∼1 s). Such rapid signalling remains to be determined but may occur via coordinated protein–protein interactions among receptor and submembrane scaffolding/signalling proteins. Scaffolding and structural proteins are important for NMDA receptor coupling to Ras/ERK signalling in hippocampus (Krapivinsky et al. 2003). Moreover, Ras, which is activated upstream of MEK and ERK1/2 in neurones, may also interact with PSD-95 (Komiyama et al. 2002). mGluR1/5 bind to members of the Homer family, including the inducible immediate early gene (IEG) Homer1a and the constitutively expressed Homer1b/c, Homer2 and Homer3 (Brakeman et al. 1997). A conserved C-terminal coiled-coil domain of Homer proteins permits their homo- (and hetero-) dimerization, allowing the cross-linking of mGluRs with other intracellular proteins (Xiao et al. 2000). In cerebellar neurones, Homer proteins form a tether linking mGluR1/5 with IP3 receptors (Tu et al. 1998) and in striatal neurones Homer1b/c links mGluR5 to ERK cascade (Mao et al. 2005). Thus, Homer proteins may participate in the submembrane organization of mGluR1α and specific scaffolding/signalling proteins which orchestrate the rapid mGluR1α-mediated intracellular signalling in interneurones.

Role of TRP channels and ERK in LTP induction

Our findings provide a molecular framework, implicating Src/ERK and TRP channels, in the mGluR1α-mediated LTP induction in interneurones. Implication of ERK/MAPK pathways has been shown in different forms of hippocampal long-term synaptic plasticity (Sweatt, 2004). Our data provide novel evidence that the mGluR1α/Src/ERK pathway is involved in LTP induction at interneurone excitatory synapses by supplying a specific Ca2+ signal via TRP channels. LTP induction also required mGluR1α-mediated intracellular Ca2+ release. Since blocking TRP channels prevented LTP, both Src/ERK activation and intracellular Ca2+ release may couple to the same effectors, TRP channels, necessary for LTP induction. Considering that TRP channels may function as both receptor- and store-operated (Clapham, 2003; Parekh & Putney, 2005), this dual mode of activation may underlie their essential role in interneurone synaptic plasticity.

ERK/MAPK cascade activation is regulated by intracellular Ca2+ (Rosen et al. 1994). Our observations that mGluR1α Ca2+ signals are ERK dependent raise the possibility of a self-reinforcing intracellular Ca2+ cascade in O/A interneurones: mGluR1α→ Src/ERK → Ca2+ signal →ERK → Ca2+ signal. Such a cascade, resulting in large and fast Ca2+ rises, may also serve to activate local protein synthesis in dendritic microdomains (Weiler & Greenough, 1993) of interneurones.

Interestingly, blockade of TRP channels prevented LTP induction and unmasked LTD at interneurone excitatory synapses. Long-term potentiation (Alle et al. 2001; Perez et al. 2001) and long-term depression (McMahon & Kauer, 1997; Laezza et al. 1999; Lei & McBain, 2004) were previously shown at different interneurone excitatory synapses in hippocampal networks (but see Alle et al. 2001; Pelkey et al. 2005). Our findings reveal that long-lasting plasticity is bi-directional at some interneurone excitatory synapses and the direction of change may depend on TRP channel regulation.

In conclusion, mGluR1α activation elicited Src- and ERK-dependent Ca2+ signalling via TRP channels and intracellular release, and this cascade was involved in LTP induction, uncovering a novel role of ERK signalling and TRP channels in cell type-specific Ca2+ signalling in hippocampal networks, which underlies long-term synaptic plasticity in interneurones.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dominique Nouel for technical assistance with two-photon microscopy and Dimitry Topolnik for help with figure preparation. This work was supported by a CIHR operating grant (J.C.L) and FRSQ (Groupe de Recherche sur le Système Nerveux Central). J.C.L. is the recipient of a Canada Research Chair in Cellular and Molecular Neurophysiology. L.T. was supported by the Savoy Foundation and A.K. by NSERC.

References

- Alle H, Jonas P, Geiger JR. PTP and LTP at a hippocampal mossy fiber-interneuron synapse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:14708–14713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251610898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atsumi S, Wakabayashi K, Titani K, Fujii Y, Kawate T. Neuronal pp60c-src(+) in the developing chick spinal cord as revealed with anti-hexapeptide antibody. J Neurocytol. 1993;22:244–258. doi: 10.1007/BF01187123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baude A, Nusser Z, Roberts JD, Mulvihill E, McIlhinney RA, Somogyi P. The metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR1 alpha) is concentrated at perisynaptic membrane of neuronal subpopulations as detected by immunogold reaction. Neuron. 1993;11:771–787. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkeley JL, Levey AI. Cell-specific extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation by multiple G protein-coupled receptor families in hippocampus. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:128–135. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonni A, Brunet A, West AE, Datta SR, Takasu MA, Greenberg ME. Cell survival promoted by the Ras-MAPK signaling pathway by transcription-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Science. 1999;28:1358–1362. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5443.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolotto ZA, Collingridge GL. Characterization of LTP induced by the activation of glutamate metabotropic receptors in area CA1 of the hippocampus. Neuropharmacology. 1993;32:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(93)90123-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brakeman PR, Lanahan AA, O'Brien R, Roche K, Barnes CA, Huganir RL, Worley PF. Homer: a protein that selectively binds metabotropic glutamate receptors. Nature. 1997;386:284–288. doi: 10.1038/386284a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W, Lanahan AA, O'Brien R, Roche K, Barnes CA, Huganir RL, Worley PF. Direct binding of activated c-Src to the β3-adrenergic receptor is required for MAP kinase activation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:38131–38134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000592200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham DE. TRP channels as cellular sensors. Nature. 2003;426:517–524. doi: 10.1038/nature02196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congar P, Leinekugel X, Ben-Ari Y, Crepel V. A long-lasting calcium-activated nonselective cationic current is generated by synaptic stimulation or exogenous activation of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors in CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5366–5379. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-14-05366.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emptage NG. Calcium on the up: supralinear calcium signaling in central neurons. Neuron. 1999;24:495–497. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English JD, Sweatt JD. Activation of p42 mitogen-activated protein kinase in hippocampal long-term potentiation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24329–24332. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraguti F, Baldani-Guerra B, Corsi M, Nakanishi S, Corti C. Activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 by metabotropic glutamate receptors. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:2073–2082. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotuhi M, Sharp AH, Glatt CE, Hwang PM, von Krosigk M, Snyder SH, Dawson TM. Differential localization of phosphoinositide-linked metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR1) and the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor in rat brain. J Neurosci. 1993;13:2001–2013. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-05-02001.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund TS, Buzsaki G. Interneurons of the hippocampus. Hippocampus. 1996;6:347–470. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:4<347::AID-HIPO1>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee CE, Benquet P, Gerber U. Group I metabotropic glutamate receptors activate a calcium-sensitive transient receptor potential-like conductance in rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 2003;546:655–664. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.032961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewal SS, York RD, Stork PJ. Extracellular-signal-regulated kinase signalling in neurons. Current Opin Neurobiol. 1999;9:544–553. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4388(99)00010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermans E, Challiss R. Structural, signalling and regulatory properties of the group I metabotropic glutamate receptors: prototypic family C G-protein-coupled receptors. Biochem J. 2001;359:465–484. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3590465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuss C, Scanziani M, Gahwiler BH, Gerber U. G-protein-independent signaling mediated by metabotropic glutamate receptors. Nature Neurosci. 1999;2:1070–1077. doi: 10.1038/15996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisatsune C, Kuroda Y, Nakamura K, Inoue T, Nakamura T, Michikawa T, Mizutani A, Mikoshiba K. Regulation of TRPC6 channel activity by tyrosine phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:18887–18894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311274200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher R, Govindarajan A, Jung H-Y, Kang H, Tonegawa S. Translational control by MAPK signaling in long-term synaptic plasticity and memory. Cell. 2004;116:467–479. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SJ, Kim YuS, Yuan JP, Petralia RS, Worley PF, Linden DJ. Activation of the TRPC1 cation channel by metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR1. Nature. 2003;426:285–291. doi: 10.1038/nature02162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komiyama NH, Watabe AM, Carlisle HJ, Porter K, Charlesworth P, Monti J, et al. SynGAP regulates ERK/MAPK signaling, synaptic plasticity, and learning in the complex with postsynaptic density 95 and NMDA receptor. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9721–9732. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-22-09721.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krapivinsky G, Krapivinsky L, Manasian Y, Ivanov A, Tyzio R, Pellegrino C, Ben-Ari Y, Clapham DE, Medina I. The NMDA receptor is coupled to the ERK pathway by a direct interaction between NR2B and RasGRF1. Neuron. 2003;40:775–784. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00645-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laezza F, Doherty JJ, Dingledine R. Long-term depression in hippocampal interneurons: joint requirement for pre- and postsynaptic events. Science. 1999;285:1411–1414. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5432.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamsa K, Heeroma JH, Kullmann D. Hebbian LTP in feed-forward inhibitory interneurons and the temporal fidelity of input discrimination. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:916–924. doi: 10.1038/nn1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapointe V, Morin F, Ratte S, Croce A, Conquet F, Lacaille J-C. Synapse-specific mGluR1-dependent long-term potentiation in interneurones regulates mouse hippocampal inhibition. J Physiol. 2004;15:125–135. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.053603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei S, McBain CJ. Two loci of expression for long-term depression at hippocampal mossy-fiber-interneuron synapses. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2112–2121. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4645-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin TA, Kong X, Haystead TA, Pause A, Belsham G, Sonenberg N, Lawrence JC., Jr PHAS-I as a link between mitogen-activated protein kinase and translation initiation. Science. 1994;266:653–656. doi: 10.1126/science.7939721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttrell LM, Ferguson SS, Daaka Y, Miller WE, Maudsley S, Della Rocca GJ, et al. Beta-arrestin-dependent formation of β2 adrenergic receptor-Src protein kinase complexes. Science. 1999;283:655–661. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5402.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBain CJ, DiChiara TJ, Kauer JA. Activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors differentially affects two classes of hippocampal interneurons and potentiates excitatory synaptic transmission. J Neurosci. 1994;14:4433–4445. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-07-04433.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccaferri G, Toth K, McBain CJ. Target-specific expression of presynaptic mossy fiber plasticity. Science. 1998;279:1368–1370. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5355.1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon LL, Kauer JA. Hippocampal interneurons express a novel form of synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 1997;18:295–305. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80269-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannaioni G, Marino MJ, Valenti O, Traynelis SF, Conn PJ. Metabotropic glutamate receptors 1 and 5 differentially regulate CA1 pyramidal cell function. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5925–5934. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-05925.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao L, Yang L, Tang Q, Samdani S, Zhang G, Wang JQ. The scaffold protein Homer1b/c links metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 to extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase cascades in neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2741–2752. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4360-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meldolesi J. Rapidly exchanging Ca2+ stores: ubiquitous partners of surface channels in neurons. News Physiol Sci. 2002;17:144–149. doi: 10.1152/nips.01385.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin F, Beaulieu C, Lacaille J-C. Selective loss of GABA neurons in area CA1 of the rat hippocampus after intraventricular kainate. Epilepsy Res. 1998;32:363–369. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(98)00033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Barbara JG, Nakamura K, Ross WN. Synergistic release of Ca2+ from IP3-sensitive stores evoked by synaptic activation of mGluRs paired with back-propagating action potentials. Neuron. 1999;24:727–737. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odell A, Scott JL, Van Helden DF. Epidermal growth factor induces tyrosine phosphorylation, membrane insertion, and activation of transient receptor potential channel 4. J Biochem. 2005;280:37974–37987. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503646200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekh AB, Putney JW., Jr Store-operated calcium channels. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:757–810. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00057.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peavy RD, Conn PJ. Phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinase in cultured rat cortical glia by stimulation of metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Neurochem. 1998;71:603–612. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71020603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelkey KA, Lavezzari G, Racca C, Roche KW, McBain CJ. mGluR7 is a metaplastic switch controlling bidirectional plasticity of feedforward inhibition. Neuron. 2005;46:89–102. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez Y, Morin F, Lacaille J-C. A hebbian form of long-term potentiation dependent on mGluR1a in hippocampal inhibitory interneurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9401–9406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161493498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pin J-P, Duvoisin R. The metabotropic glutamate receptors: structure and functions. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1–26. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)00129-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rae MG, Irving AJ. Both mGluR1 and mGluR5 mediate Ca2+ release and inward currents in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Neuropharmacology. 2004;46:1057–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey IS, Delling M, Clapham DE. An introduction to trp channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:619–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040204.100431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renaud J, Emond M, Meilleur S, Psarropoulou C, Carmant L. AIDA, a class I metabotropic glutamate-receptor antagonist limits kainate-induced hippocampal dysfunction. Epilepsia. 2002;43:1306–1317. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.10402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen LB, Ginty DD, Weber MJ, Greenberg ME. Membrane depolarization and calcium influx stimulate MEK and MAP kinase via activation of Ras. Neuron. 1994;12:1207–1221. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90438-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanziani M, Gahwiler BH, Charpak S. Target cell-specific modulation of transmitter release at terminals from a single axon. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:12004–12009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.12004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strübing C, Krapivinsky G, Krapivinsky L, Clapham DE. TRPC1 and TRPC5 form a novel cation channel in mammalian brain. Neuron. 2001;29:645–655. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweatt JD. Mitogen-activated protein kinases in synaptic plasticity and memory. Current Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:311–317. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tempia F, Alojado ME, Strata P, Knopfel T. Characterization of the mGluR1-mediated electrical and calcium signaling in Purkinje cells of mouse cerebellar slices. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:1389–1397. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.3.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thandi S, Blank JL, Challiss RA. Group-I metabotropic glutamate receptors, mGlu1a and mGlu5a, couple to extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) activation via distinct, but overlapping, signalling pathways. J Neurochem. 2002;83:1139–1153. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topolnik L, Congar P, Lacaille J-C. Differential regulation of mGluR- and AMPAR-mediated dendritic Ca2+ signals by pre- and postsynaptic activity in hippocampal interneurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:990–1001. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4388-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth K, McBain CJ. Afferent-specific innervation of two distinct AMPA receptor subtypes on single hippocampal interneurons. Nature Neurosci. 1998;1:572–578. doi: 10.1038/2807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tozzi A, Bengtson CP, Longone P, Carignani C, Fusco FR, Bernardi G, Mercuri NB. Involvement of transient receptor potential-like channels in responses to mGluR-I activation in midbrain dopamine neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:2133–2145. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu JC, Xiao B, Yuan JP, Lanahan AA, Leoffert K, Li M, Linden DJ, Worley PF. Homer binds a novel proline-rich motif and links group 1 metabotropic glutamate receptors with IP3 receptors. Neuron. 1998;21:717–726. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80589-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatachalam K, Zheng E, Gill DL. Regulation of canonical transient receptor potential (TRPC) channel function by diacylglycerol and protein kinase C. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:29031–29040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302751200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiler IJ, Greenough WT. Metabotropic glutamate receptors trigger postsynaptic protein synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:7168–7171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhall G, Gee CE, Robitaille R, Lacaille J-C. Membrane potential and intracellular Ca2+ oscillations activated by mGluRs in hippocampal stratum oriens/alveus interneurons. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:371–382. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.1.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao B, Tu JC, Worley PF. Homer: a link between neural activity and glutamate receptor function. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10:370–374. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan LL, Adams JP, Swank M, Sweatt JD, Johnston D. Protein kinase modulation of dendritic K+ channels in hippocampus involves a mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J Neurosci. 2002;22:4860–4868. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-12-04860.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J, Lipinski M, Degterev A. Diversity in the mechanisms of neuronal cell death. Neuron. 2003;40:401–413. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00601-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W, Bianchi R, Wang M, Wong RK. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 is required for the induction of group I metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated epileptiform discharges. J Neurosci. 2004;24:76–84. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4515-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]