Abstract

Previous studies have shown that β-carotene 15,15′-monooxygenase catalyzes the cleavage of β-carotene at the central carbon 15,15′-double bond but cleaves lycopene with much lower activity. However, expressing the mouse carotene 9′,10′-monooxygenase (CMO2) in β-carotene/lycopene-synthesizing and -accumulating Escherichia coli strains leads to both a color shift and formation of apo-10′-carotenoids, suggesting the oxidative cleavage of both carotenoids at their 9′,10′-double bond. Here we provide information on the biochemical characterization of CMO2 of the ferret, a model for human carotenoid metabolism, in terms of the kinetic analysis of β-carotene/lycopene cleavage into β-apo-10′-carotenal/apo-10′-lycopenal in vitro and the formation of apo-10′-lycopenoids in ferrets in vivo. We demonstrate that the recombinant ferret CMO2 catalyzes the excentric cleavage of both all-trans-β-carotene and the 5-cis- and 13-cis-isomers of lycopene at the 9′,10′-double bond but not all-trans-lycopene. The cleavage activity of ferret CMO2 was higher toward lycopene cis-isomers as compared with β-carotene as substrate. Iron was an essential co-factor for the reaction. Furthermore, all-trans-lycopene supplementation in ferrets resulted in significant accumulation of cis-isomers of lycopene and the formation of apo-10′-lycopenol, as well as up-regulation of the CMO2 expression in lung tissues. In addition, in vitro incubation of apo-10′-lycopenal with the post-nuclear fraction of hepatic homogenates of ferrets resulted in the production of both apo-10′-lycopenoic acid and apo-10′-lycopenol, respectively, depending upon the presence of NAD+ or NADH as cofactors. Our finding of bioconversion of cis-isomers of lycopene into apo-10′-lycopenoids by CMO2 is significant because cis-isomers of lycopene are a predominant form of lycopene in mammalian tissues and apo-lycopenoids may have specific biological activities related to human health.

Carotenoids are lipophilic plant pigments with polyisoprenoid structures, typically containing a series of conjugated double bonds in the central chain of the molecule, which makes them susceptible to oxidative cleavage, and isomerization from trans to cis forms, with the formation of potentially bioactive metabolites. Knowledge of the biological effects of carotenoids, particularly for the impact of oxidation on these carotenoids and the potential for beneficial effects of small quantities or harmful effects of large quantities of the resulting metabolic products, has been reviewed recently (1). For provitamin A carotenoids, such as β-carotene, α-carotene, and β-cryptoxanthin, central cleavage is a major pathway leading to vitamin A formation (2, 3). This pathway has been substantiated by the cloning of the central cleavage enzyme at their 15,15′-double bond, β-carotene 15,15′-monooxygenase (CMO1,2 formerly called β-carotene 15,15′-dioxygenase) in different species (4, 5), further classification of this enzyme as a non-heme iron monooxygenase (6), and recent biochemical and structural characterizations (7–11). Very recently, Poliakov et al. (10) demonstrate that the four conserved histidines and one conserved glutamate are required for the iron coordination and catalytic activity of CMO1, which provided the first biochemical insight into the catalytic mechanism of CMO1. An alternative pathway for carotenoid metabolism in mammals, the excentric cleavage pathway, had been a controversial issue among scientists for several decades. We have previously provided evidence for random cleavage of the β-carotene molecule, and we demonstrated that a series of homologous carbonyl cleavage products are produced, including retinal, β-apo-14′-, 12′-,10′-, and 8′-carotenals, β-apo-13-carotenone, and retinoic acid from β-carotene in tissue homogenates of humans, ferrets, and rats (12–14). However, the existence of the excentric cleavage pathway for β-carotene was not confirmed until the molecular identification of β-carotene 9′,10′-monooxygenase (CMO2) in humans and mice (15). These investigators showed that the mouse CMO2, expressed in the β-carotene-synthesizing and -accumulating E. coli strains, can cleave β-carotene at its 9′,10′-double bond to form β-apo-10′-carotenal, β-apo-10′-carotenol, and its ester (15). The CMO2 belongs to a family of oxygenases (15), such as mammalian CMO1 (7) and retinal pigment epithelial RPE65 (16), epoxycarotenoid-cleaving enzyme in plants (17), and cyanobacterial apocarotenoid 15,15′-oxygenase (11, 18). However, no further characterization of CMO2 and kinetic analysis of β-carotene cleavage into apo-10′-carotenoids by CMO2 has been reported.

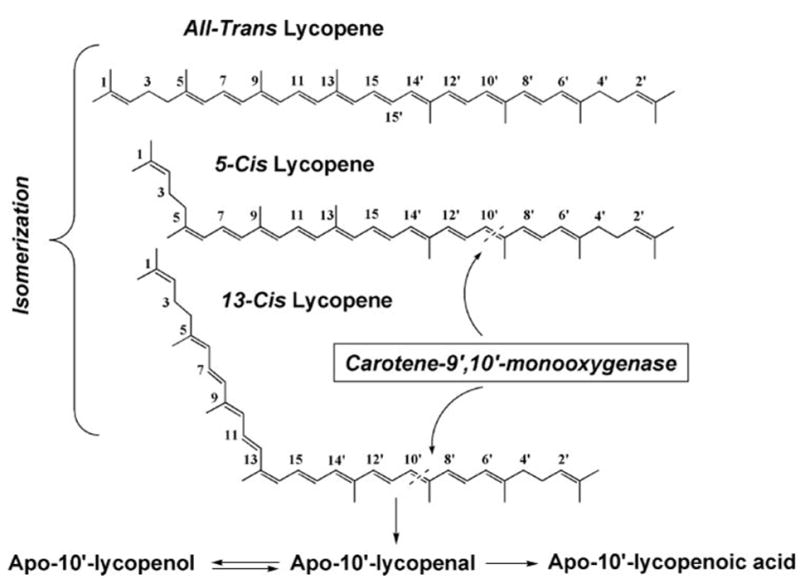

Lycopene, a major carotenoid from tomatoes and tomato products and a predominant carotenoid in human plasma and tissue, has been shown to be beneficial to human health against cardiovascular disease and cancer. Because lycopene has a chemical structure similar to β-carotene, it is possible that lycopene undergoes both central and excentric cleavage as well. This is supported by findings that lycopene-synthesizing and -accumulating E. coli strains exhibit a color shift after expressing mouse CMO1, but this activity was much lower toward lycopene, as compared with β-carotene (7). In addition, Lindqvist and Andersson (9) reported that CMO1 catalyzes the cleavage of β-carotene and β-cryptoxanthin at the central carbon 15,15′-double bond but does not cleave lycopene. In terms of CMO2, lycopene-synthesizing and -accumulating E. coli strains exhibit a color shift after expressing mouse CMO2 (15), suggestive of a cleavage reaction. However, direct evidence regarding lycopene cleavage by CMO2 at its 9′,10′-double bond to form apo-10′-lycopenoids in mammals both in vitro and in vivo is still lacking (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic illustration of a possible merabolic pathway of lycopene.

Recently, we have provided evidence that lycopene can protect against smoke-related lesions in the lungs (19) and stomach (20) of the ferrets, which is an excellent model for use in mimicking carotenoid metabolism in humans, considering the similarities between ferrets and humans in terms of carotenoid absorption, oxidative cleavage, and their biological functions (21). However, although all-trans-lycopene is the predominant isomer in the supplement, we and other investigators observed dramatic increases in the cis-isomers of lycopene, including 5-cis-, 13-cis-, and 9-cis-isomers, in the tissues of ferrets (19, 20, 22). More understanding of the significance of the metabolism of cis-lycopene will help to further elucidate the biological functions of lycopene.

In the present study, using the ferret as a model, we cloned and expressed ferret CMO2 in a baculo-virus system, and we characterized the CMO2 kinetic properties using both β-carotene and lycopene as substrates in vitro. Furthermore, we examined the tissue expression of CMO2 and the formation of apo- 10′-lycopenoids in the ferrets supplemented with lycopene in vivo.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals

Lycopene, apo-10′-lycopenal, apo-10′-lycopenol, apo-10′-lycopenoic acid, β-carotene, and lycopene 10% dry power (Lycovit® 10%) were provided by BASF Inc, Ludwigshafen, Germany. Ammonium acetate was purchased from Sigma. HPLC-grade solvents were obtained from J. T. Baker Inc. Methyl-tert-butyl ether was purchased from Aldrich. Substrate stock solutions of all-trans-β-carotene and lycopene were prepared in tetrahydro-furan under red light and stored at −80 °C until use. All standards were stored at −80 °C until used.

Cloning of a cDNA Encoding CMO2 from the Ferret

Reverse transcription-PCRs were performed for cloning of full-length cDNA encoding ferret CMO2. The first-strand cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcriptase using 2 μg of total RNA isolated from ferret liver as the template and pd(N)6 or NotI-d(T)18 as primers. PCR was carried out using 5 pair of primers for CMO2, designed as reported cDNA sequences for a human carotene excentric cleavage enzyme (GenBankTM accession number NM_031938). The 5′-end of the cDNA was prepared by 5′-RACE using a 5′/3′-RACE kit (Roche Applied Science). The PCR products were ligated into the pCRII TOPO vector using a TA cloning kit (Invitrogen) and sequenced using a GigDye terminator cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The complete ferret CMO2 coding sequence was re-amplified by Tgo DNA polymerase (Roche Applied Science) from a ferret liver cDNA library, made from SuperScript Lambda System for the cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen), using the up primer from CMO2, 5′-ATGGAGGGTACCGATCAG-AAAAAGGC-3′, and the down primer 5′-TCAGACTGTTA-CAAAGGTACCGTGG-3′. The PCR cloning was inserted into the pCRII TOPO vector (named pCRII-fCMO2), and the sequence was confirmed.

Expression of Ferret CMO2 in Mammalian Cells and Immunofluorescence

To generate the ferret CMO2 expression vector, the entire coding sequence of the ferret CMO2 was subcloned into the mammalian expression vector pRc-HA and fused in-frame to an HA tag (hemagglutinin epitope) at the N terminus. The plasmid is referred to as pRcHA-fCMO2. COS-1 cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, and the transfections of ferret CMO2 were performed using FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science). COS-1 cells were seeded on 6-well plates and transfected at 50% confluence with 2 μg of an empty vector or expression vector encoding HA-tagged ferret CMO2 (pRcHA-fCMO2). After 40 h of transfection, the aliquots of total cell lysates were prepared by boiling the cell pellet in reducing Laemmli sample buffer, and proteins were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE. Expression of the fusion protein of ferret CMO2 was detected by Western blotting with the anti-HA monoclonal antibody, HA.11 (Covance, Berkeley, CA). For immunofluorescence, COS-1 cells on coverslips in 6-well plates were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS for 20 min, rinsed in PBS, permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100/PBS for 5 min, and blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 30 min. Anti-HA tag antibody (monoclonal antibody; Covance, CA) was diluted 1:100 in 0.1% bovine serum albumin/PBS and applied to coverslips for 1 h. Coverslips were rinsed in PBS and incubated in fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:100, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) for 30 min. Images were viewed by fluorescence microscopy.

Generation of Antibody against Ferret CMO2

The N-terminal 273 amino acids of CMO2 from ferret were fused in-frame to the glutathione S-transferase gene with the pGEX-20 vector and expressed in E. coli. BL21. The fusion proteins were isolated with glutathione-Sepharose resin and used to immunize rabbits at the Animal Pharm Services Inc. (Healdsburg, CA). The polyclonal antibody was purified from crude serum of rabbits by using affinity purification methods. The specificity of the antibody against ferret CMO2 was examined by its cross-reaction with purified CMO1 from mouse (generously provided by Dr. T. M. Redmond, NEI, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda) and human (kindly provided by Drs. A. Lindqvist and S. Andersson, University of Texas, Dallas).

Expression of Ferret CMO2 in SF9 Cells

The complete ferret CMO2 coding sequence was subcloned from pRcHA-fCMO2 plasmid into the baculovirus expression vector pFastBac1 (Invitrogen) by PCR using the BamHI/SpeI site. Spodoptera frugiperda 9 (SF9) cells were transfected with the CMO2 bacmid DNA, and the viral titer of recombinant CMO2 was amplified by propagation in SF9 cells. Then SF9 cell were infected with the CMO2 recombinant baculovirus for 3 days, and cell pellets were centrifuged, washed once with cold PBS, and stored at −80 °C until use. Expression of ferret CMO2 protein in SF9 cells was confirmed by both Western blotting analysis with the purified polyclonal antibody against ferret CMO2 and Coomassie Blue stain.

Enzyme Kinetic Assay

All of procedures for the enzyme preparation were carried out on ice. The SF9 cell pellets containing either infected ferret CMO2 recombinant baculovirus or uninfected were resuspended in 0.5 ml of buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM KCl, 0.1% Tween 20) and homogenized in Potter-Elvehjem homogenizer for 60 s (or stroked 20 times). The homogenates were clarified by centrifugation (4 °C) at 10,000 μg for 15 min. The collected supernatants were either immediately used for enzyme assay or stored at −80 °C until further use. The aliquots of carotenoids in tetrahydrofuran (all-trans-β-carotene and lycopene stock solution) as substrates were dried by N2 under red light and then prepared in 4% Tween 40 in acetone, which is again evaporated by N2. The dried substrates were solubilized in deionized water and vortexed to obtain a clear micellar solution. The enzyme reactions were performed in a volume of 1 ml of assay buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM KCl, 10 μM Fe2SO2, 3 mM NAD, 0.3 mM DTT with the enzyme (−6 mg of protein of the supernatant or various concentrations as indicated). The mixtures were preincubated at 37 °C for 5 min, and the cleavage reactions were initiated by adding 50 μl of the substrate (β-carotene or lycopene at various concentrations). After incubation for 60 min at 37 °C in the dark with gentle shaking, the reactions were stopped by adding 1.5 ml of 100% ethanol. The incubation mixtures were extracted twice by using 3 ml of hexane/butyl methyl ether (1:1 v/v). The combined extract was dried by N2 under red light and dissolved in 100 μl of ethanol and analyzed by the HPLC system described below.

HPLC Analysis

A gradient reverse phase HPLC was used for the analysis of carotenoids and their polar metabolites as described previously, with minor modifications (23). Briefly, the gradient reverse phase HPLC system consisted of a Waters 2695 separations module and a Waters 2996 photodiode array detector. The products of β-carotene were analyzed on a reverse phase C18 column (3 μm, 4.6 × 85 mm; PerkinElmer Life Sciences) with a flow rate of 1 ml/min. The gradient procedure was as follows: 1) 100% solvent A (acetonitrile, tetrahydrofuran, 1% ammonium acetate, 50:20:30, v/v) was used for 4 min, followed by a 6-min linear gradient to 50% solvent A, 50% solvent B (acetonitrile, tetrahydrofuran, 1% ammonium acetate, 50:44:6, v/v/v); 2) a 9-min hold followed by a 2-min linear gradient to 100% solvent B and then 100% solvent B for 10 min. A C30 carotenoid column (3 μm, 4.6 × 150 mm YMC; Waters) was used for separating the cleavage products of lycopene. The mobile phase was methanol, methyl butyl ether, 1.5% ammonium acetate (83: 15:2, v/v/v) in solvent A and methanol, methyl butyl ether, 1.0% ammonium acetate (8:90:2, v/v/v) in solvent B. Elution was at 1 ml/min with the following gradients: 100% solvent A at 3 min, proceeding linearly to 70% solvent A, 30% solvent B at 10 min, a 5-min hold followed by a 9-min linear gradient to 45% solvent A; a 2-min hold and then linear gradient to 95% solvent B at 33 min, and then a 6-min hold. The column was flushed with 100% solvent A for 15 min before the next injection. The Waters 2996 programmable photodiode array detector was set at 455 nm for carotenoid metabolites. In this HPLC system, apo-10′-carotenal and apo-10′-lycopenal were eluted at 14.9 and 11.6 min, respectively. Individual carotenoids (β-apo-10′-carotenal and apo-10′-lycopenal) were identified by co-elution with standards and absorption spectral analysis.

Examination of CMO2 Tissue Expression

Total RNA was extracted by TriPure Isolation Reagent (Roche Applied Science) from different tissues of ferrets. RNA (350 ng) was transcribed to first strand cDNA by Moloney murine leukemia virus-reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) with 5 μM of p(dN)6 random primer. The real time quantitative PCR assay was carried out using ABI Prism 7000 sequence detection system. The reaction was initiated by carry over decontamination at 50 °C for 2 min and held at 95 °C for 10 min for hot start, and then followed by 40 cycles of amplification as follows: 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. Ferret β-actin was used as the endogenous control. The TaqMan probes and primers from the sequence of ferret for both CMO2 and β-actin were generated by Assays-by Design Service (ABI, Foster, CA). The following sets of primer and probes were used: CMO2, forward 5′-GGAGGGTACCG-ATCAGAAAAAGG-3′, reverse 5′-GTTAGCAGCGGTGCA-ATACAC-3′, and FAM probe TCGCGTACCGACCGCT; β-actin, forward 5′-GCCCCACGCCATCCT-3′, reverse 5′-CC-GCGCTCGGTAAGGA-3′, and FAM probe CAGGTCCCGG-CCAGCCA. The comparative Ct method was used for the quantitation of gene expression.

Animal Study, Lung Tissue Extraction, and HPLC Analyses

The lung tissues of ferrets from our previous study (19) were used in the present study. The maintenance and husbandry of ferrets, as well as the procedures of lycopene supplementation in ferrets, have been described in our previous paper (19). Briefly, male adult ferrets from Marshall Farms (North Rose, NY) were fed a semi-purified ferret diet (Research Diets, Inc., New Brunswick, NJ) and supplemented with lycopene for 9 weeks. Lycopene (Lycovit® 10%, BASF, Ludwigshafen, Germany, 95% as all-trans-lycopene) was dissolved into 0.5 ml of corn oil and fed orally (no gavage) to ferrets (4.3 mg/kg body weight per day in the ferret, which is equivalent to 60 mg per day in a 70-kg human) for 9 weeks. The non-lycopene supplemented ferrets were given the placebo and corn oil only. The lung tissue (0.5 g wet weight) extraction and HPLC analyses have been described elsewhere (19). In this HPLC system, apo-10′-lycopenoic acid, apo-10′-lycopenol, and apo-10′-lycopenal eluted at 5.3, 10.2, and 11.6 min, respectively. Lycopene metabolites were quantified relative to the internal standard by determining peak areas calibrated against known amounts of the standard.

The Incubation of Apo-10′-lycopenal with the Post-nuclear Fraction of Ferret Liver

Ferret liver (~0.5 g) was homogenized with 5 ml of cold Tris buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM KCl, 0.5 mM DTT, pH 8.0) using Ultra Turrax T8 homogenizer (IKA, in Germany). The homogenate was centrifuged at 1800 × g at 4 °C for 20 min. The resulting supernatant represents the post-nuclear fraction for the incubations. The reactions were carried out in a final volume of 1 ml of assay buffer A containing 5 mg of post-nuclear fraction of liver homogenates with or without adding cofactors (3 mM NAD+, or 3 mM NADH). The mixtures were preincubated at 37 °C for 5 min, and then the reactions were initiated by adding 10 μl of apo-10′-lycopenal as substrate, at the indicated concentrations (2 and 10 μM). After 1 h of shaking in a 37 °C water bath under red light, the incubations were terminated by addition of 1.5 ml of ethanol. The incubation mixtures were extracted, dried, dissolved in 100 μl of ethanol, and subjected to analysis by HPLC, as described above.

RESULTS

Molecular Cloning, Expressing, and Intracellular and Tissue Distribution of Ferret CMO2

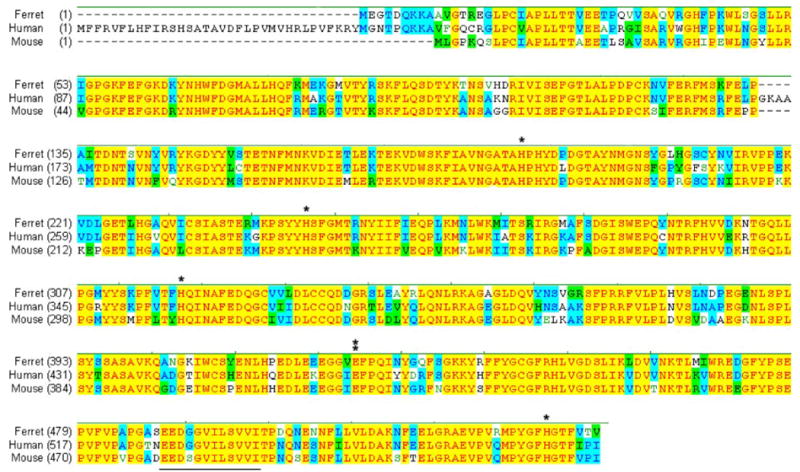

To identify potential homologues of ferret CMO2, reverse transcription-PCR was carried out using 5 pairs of primers, designed from the reported cDNA sequence of CMO2 from humans (GenBankTM accession number NM_031938), and the first-strand cDNA from ferret liver as the template. The products of PCR were cloned into the vector pCRII-TOPO, and the sequence was analyzed. Then the 5′-end of the cDNA was prepared by RACE-PCR using a specific primer derived from the sequence of ferret CMO2. Individual sequences of PCR fragments were assembled into a contiguous stretch of 1993 bases. The cDNA contained an open reading frame of the expected size in addition to 5′- and 3′-untranslated sequences. The alignment of DNA sequences of CMO2 from the ferret showed 87% homology with human CMO2 and 81% homology with mouse CMO2. The entire coding region of ferret CMO2 is 1.62 kb in length and encodes a predicted protein of 540 amino acids (deposited in the GenBankTM with accession number AY527150). There were four conserved histidine and one glutamate residues in the ferret CMO2 (Fig. 2), which have been demonstrated as putative iron-binding residues in CMO1 (10). The deduced amino acid sequence of ferret CMO2 was 82% identical to the human CMO2 and 79% identical to the mouse CMO2 (Fig. 2). Most of the amino acid differences among these three species occur in the N-terminal region of the protein. In the C-terminal region of the ferret CMO2, there was a conserved domain EDDGGVILVVI (Fig. 2) that has been considered as a CMO family signature sequence (10).

FIGURE 2. Comparison of the deduced amino acid sequences of the CMO2 among ferret, human, and mouse.

Identity is indicated in yellow among three species and in blue between two species. The four conserved histidines (indicated by a single asterisk) and one glutamate (indicated in double asterisks) existed in the ferret CMO2, which has been demonstrated as putative iron-binding residues in all oxygenase family members (10). There CMO family signature sequence is underlined. The nucleotide sequence for the carotene 9′,10′-monooxygenase gene of ferret has been deposited in the GenBankTM with accession number AY527150.

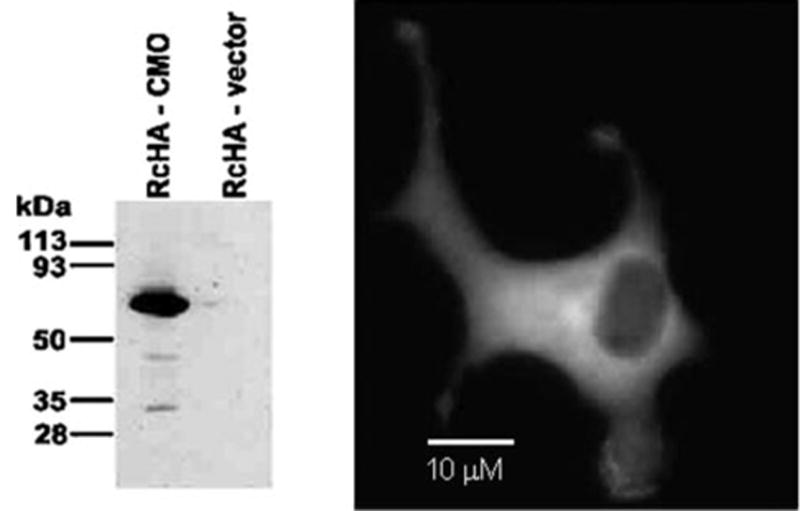

To determine the intracellular localization of ferret CMO2, the entire coding sequence of the ferret CMO2, obtained by PCR with Tgo DNA polymerase from the ferret liver cDNA library, was cloned into the mammalian expression vector pRc-HA. The cDNA was fused in-frame to the HA tag at the N terminus, referred as pRcHA-fCMO2, and expressed in COS-1 cells by transient transfection. The overexpression of the enzyme was confirmed by immunoblotting with an anti-HA antibody (Fig. 3, left, the apparent molecular mass of the protein band was ~60 kDa, as predicted). The intracellular localization of ferret CMO2 using fluorescence microscopy showed intense cytoplasmic staining without apparent nuclear staining (Fig. 3, right). To further verify that the ferret CMO2 is a homologue of human CMO2, the homogenate of COS-1 cells transfected with either pRcHA-fCMO2 or vector alone was incubated with all-trans-β-carotene for 60 min at 37 °C, and the products of the reaction were analyzed by reverse phase HPLC at 450 nm. We detected one compound from all-trans-β-carotene, which has the exact same retention time and identical spectrum with absorption maxima at 448 nm as that of an authentic standard of β-apo-10′-carotenal (data not shown). Because of variations in the transfection efficiency of CMO2 in COS-1 cells, the recombinant proteins of ferret CMO2 were expressed in a baculovirus system for enzyme kinetic assay as described below.

FIGURE 3. Expression (left panel) and cytoplasmic localization (right panel) of ferret CMO2 in COS-1 cells.

COS-1 cells were transfected with either an empty vector or expression vector encoding HA-tagged ferret CMO2 as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The lysates of transfected cells were analyzed by Western blotting with an antibody directed against the HA epitope tag encoded at the N terminus of each protein. For the localization of ferret CMO2 fusion protein, COS-1 cells on coverslips transfected with the expression vector encoding HA-tagged ferret CMO2 were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS for 20 min and incubated with an anti-HA tag monoclonal antibody (Covance), followed by a green fluorescent secondary antibody. The images were viewed by fluorescence microscopy.

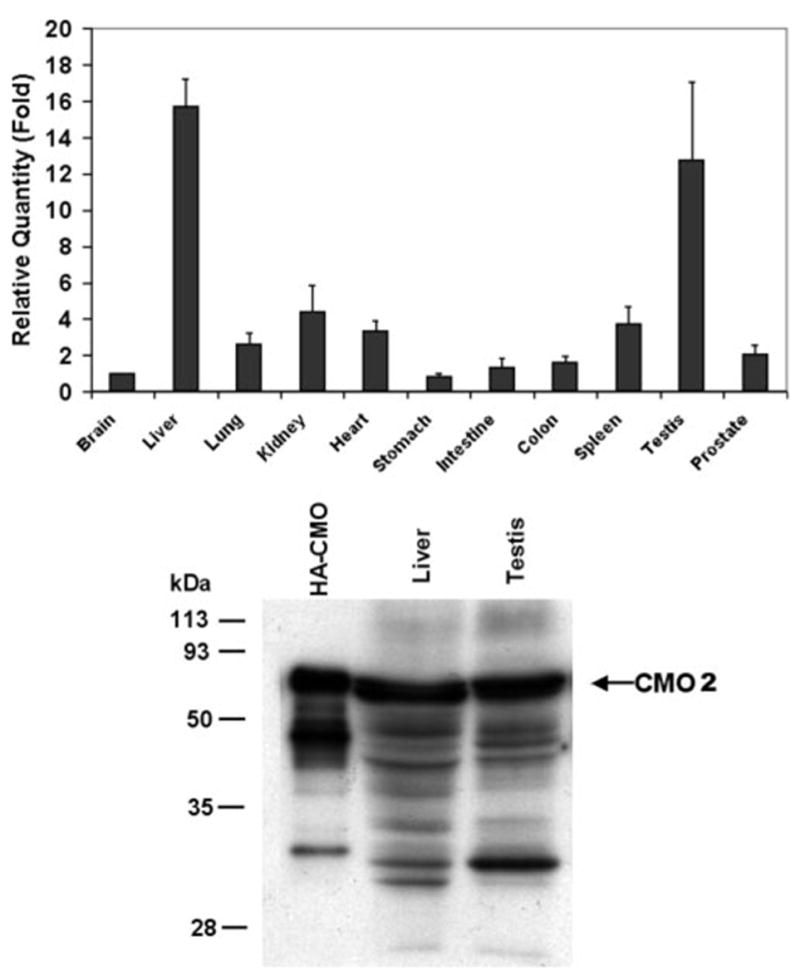

To determine the tissue distribution of the CMO2 mRNA in ferret, real time PCR was performed on a variety of ferret tissues using the primers from ferret CMO2 and β-actin as an endogenous reference. Our results showed that the CMO2 was expressed in a variety of tissues, including liver, testis, heart, spleen, lung, intestine, colon, stomach, kidney, bladder, and prostate (Fig. 4, upper panel). The expression of this enzyme in the liver and testis was relatively higher than other tissues. Because of the abundance of the CMO2 in these two tissues, the CMO2 was detected by immunoblotting with a purified polyclonal antibody against the ferret CMO2 (Fig. 4, lower panel). The specificity of the antibody for the detection of CMO2 was confirmed by much lower binding activity (50 times lower) to purified CMO1 from either human or mouse (data not shown).

FIGURE 4. Tissue distribution of ferret CMO2.

The relative levels (means ± S.D., n = 3) of CMO2 mRNA in various tissues of ferret were determined by real time PCR using brain as a reference organ and β-actin levels as a reference gene (upper panel ). The procedure for the real time PCR analysis was described under “Experimental Procedures.” Lower panel, the protein expression of CMO2 in ferret liver and testis was demonstrated by Western blot analysis using a purified polyclonal antibody, which is specifically recognized ferret CMO2 as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The HA-fCMO2 fusion protein from COS-1 cells was used as a positive control.

Enzyme Kinetic Study for Cleavage of β-Carotene Using a Recombinant Ferret CMO2

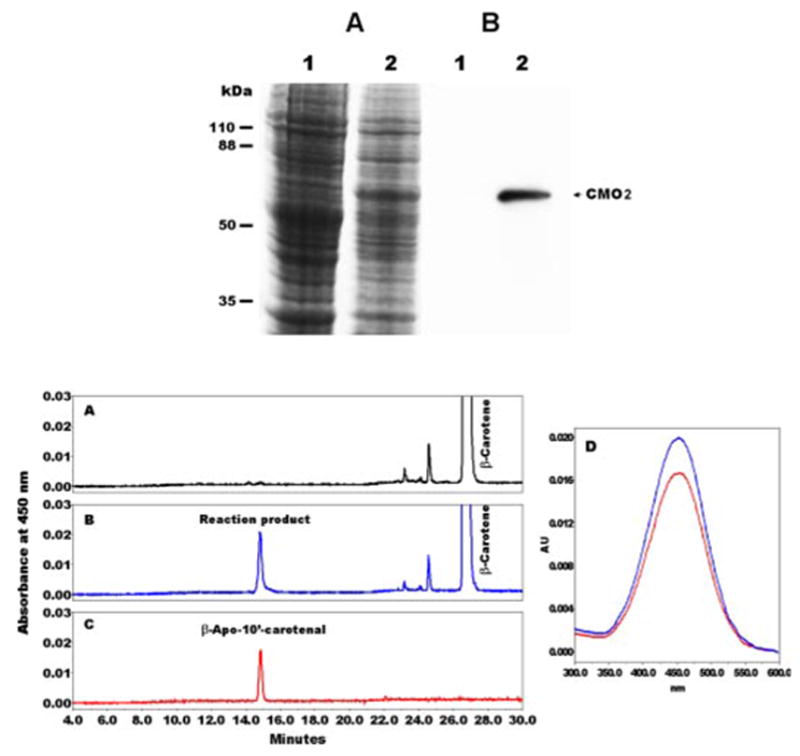

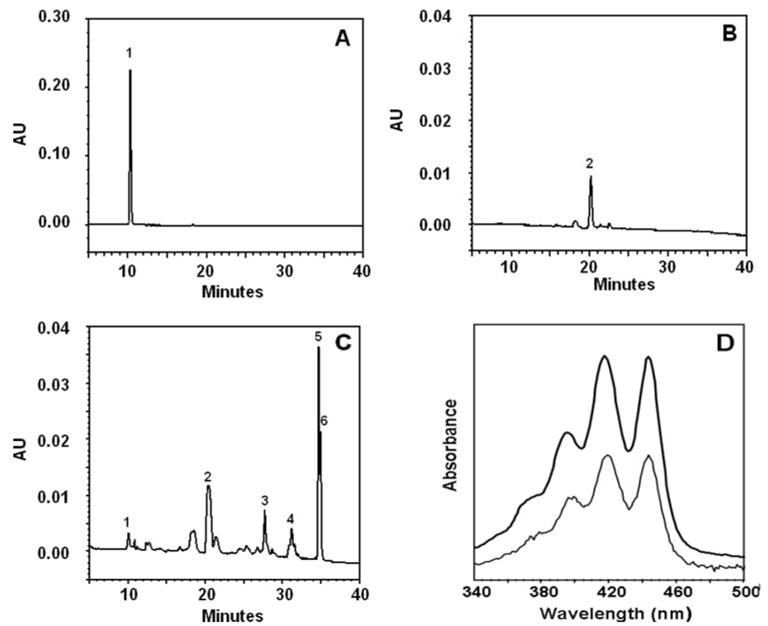

To confirm that the recombinant ferret CMO2 was expressed in a baculovirus expression system, we demonstrate the protein as ~60 kDa consistent with the molecular weight that has been detected in transfected COS-1 cells by Coomassie Blue stain and immunoblotting analysis (Fig. 5, upper panel). For the enzymatic activity, the homogenates of insect cells expressing ferret CMO2 were incubated with ~3 μM all-trans-β-carotene, and β-apo-10′-carotenal was the sole cleavage product as identified by HPLC at 450 nm (Fig. 5). Both the retention time (14.9 min) and spectrum (Fig. 5, lower panel, D) of the reaction product were identical to that of standard β-apo-10′-carotenal. Only trace amounts of other peaks were detected in two control incubations done with uninfected insect cell homogenates (Fig. 5, lower panel, A) or without cell homogenates (data not shown). These minor peaks represent the products of nonenzymatic metabolism of β -carotene, as shown previously (12).

FIGURE 5. Expression of ferret CMO2 in SF9 insect cells and identification of cleavage product from β-carotene by HPLC analysis.

Ferret CMO2 was expressed in SF9 insect cells by baculovirus as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Upper panel, the cell lysates from uninfected (lane 1) and ferret CMO2 baculovirus-infected (lane 2) insect cells were boiled in reducing sample buffer and subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE. The protein expression in insect cells can be detected by Coomassie Blue stain (A, upper panel), and the proteins were also transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and detected with CMO2-specific polyclonal antibody (B, upper panel). Lower panel, HPLC profile of the cleavage products of all-trans-β-carotene by ferret CMO2 enzyme. All-trans-β-carotene (3 μM) was incubated with the homogenates from either uninfected (A) or ferret CMO2 baculovirus-infected (B) insect cells for 1 h at 37 °C as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The cleavage products extracted from the incubation mixture were separated by reverse phase HPLC using a C18 column. A peak corresponding to authentic β-apo-10′-carotenal standard (C) was detected at 450 nm only in the incubation mixture with the homogenates of ferret CMO2 baculovirus-infected cells (B) but not in that of uninfected cells (A). D, spectral analysis of the cleavage product (blue line) of all-trans-β-carotene versus β -apo-10′-carotenal standard (red line). Both the retention time and absorption spectrum of the product from all-trans-β-carotene matched exactly with that of standard β-apo-10′-carotenal.

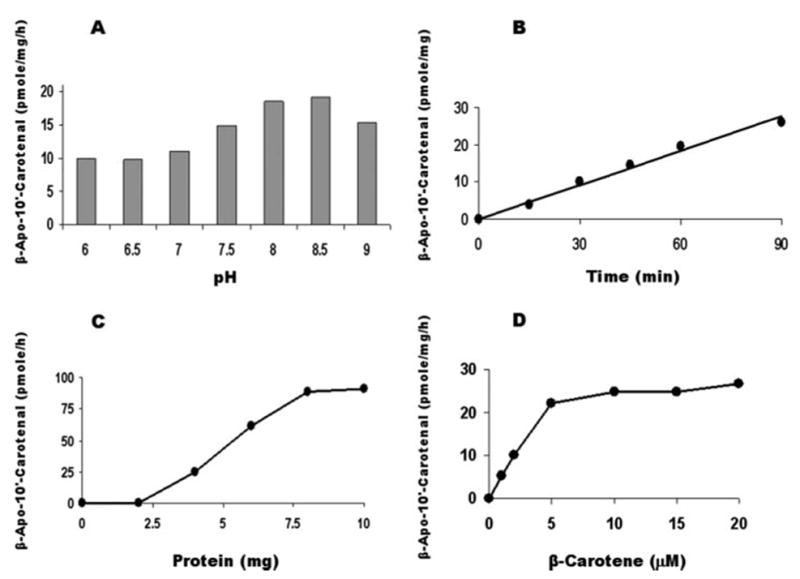

The production of β-apo-10′-carotenal from all-trans-β-carotene was pH-dependent with the pH optimum occurring between 8.0 and 8.5 (Fig. 6A, and was time-dependent and linear for 90 min (Fig. 6B). The formation of β-apo-10′-carotenal from all-trans-β-carotene was linear up to 8 mg of protein/ml, and only a slight increase of β-apo-10′-carotenal was achieved by increasing the protein concentration to 10 mg/ml (Fig. 6C). The effect of all-trans-β-carotene concentration on the production of apo-10′-carotenal from β-carotene was linear up to 5 μM and only slightly increased at 20 μM (Fig. 6D). The reaction fit the Michaelis-Menten enzyme kinetic model (software for enzyme kinetics EZ-Fit 5.03; Amherst, NH), and the estimated Km and Vmax values of the ferret CMO2 with β-carotene as substrate were 3.5 ± 1.1 μM β -carotene and 32.2 ± 2.9 pmol of β-apo-10′-carotenal/mg/h, respectively. The formation of β-apo-10′-carotenal from all-trans-β-carotene was not significantly decreased by the deletions of NAD+ and DTT (data not shown) but was significantly decreased by the deletion of Fe2+ (73.7, 72.1, and 56.6% lower from three independent experiments, as compared with that of the complete incubation system) from the incubation mixture, indicating that iron was an essential co-factor for the reaction.

FIGURE 6. Effects of pH, time, protein, and substrate concentrations on β-apo-10′-carotenal productions by ferret CMO2.

A, pH optimum of the enzyme was detected at the indicated pH value in the presence of 6 mg of homogenate protein containing ferret CMO2 and 3 μM all-trans-β-carotene at 37 °C for 1 h; B, all-trans-β-carotene (3 μ M) was incubated with 6 mg of homogenate expressing ferret CMO2 at 37 °C for various time points; C, the incubations were carried out using various protein concentrations of cell homogenates expressing ferret CMO2 with 3 μM all-trans-β-carotene at 37° for 1 h; and D, the effect of substrate concentration was conducted with homogenates of insect cells expressing ferret CMO2 with various all-trans-β-carotene concentration. The enzyme reactions were conducted in a volume of 1 ml of assay buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM KCl, 10 μM Fe2SO2, 3 mM NAD, 0.3 mM DTT, and 6 mg of protein of the insect cell homogenates expressing ferret CMO2 at 37 °C for 60 min, otherwise as indicated on the figures. The procedures for the incubation, extraction, and HPLC analysis were described under “Experimental Procedures.” The data are the average of two independent experiments. The variation in the data between the two experiments was less than 3% of the data average.

Enzyme Kinetic Study for Cleavage of Lycopene by Ferret CMO2

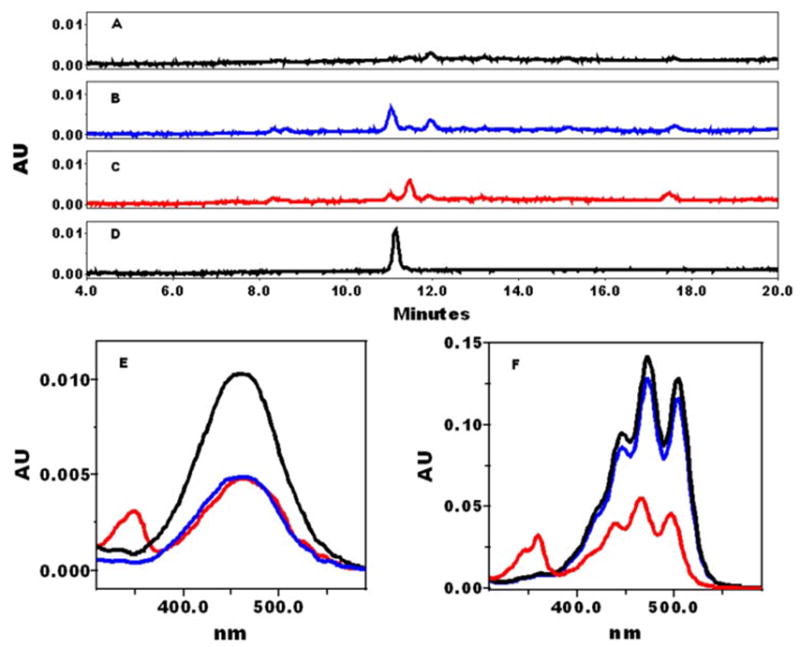

To investigate whether lycopene could be cleaved by CMO2 at its 9′,10′-double bond, the incubation assay was carried out under the conditions described above using lycopene as the substrate. We could not detect any significant amount of metabolites after the incubation with all-trans-lycopene (containing 97% as all-trans-lycopene) as the substrate (Fig. 7A). However, when the mixture of lycopene containing 38% 5-cis-isomer was used as the substrate in the incubation, there was a new product identified by HPLC analysis (Fig. 7B). This peak (Fig. 7B, peak 1), with a retention time of 11.2 min, matched exactly the retention time of authentic apo-10′-lycopenal standard at 11.2 min (Fig. 7D). In addition, this compound had the same absorption maximum (λmax = 462 nm; Fig. 7E, blue line) as apo-10′-lycopenal standard (λmax = 462 nm; Fig. 7E, black line). Because 5-cis-lycopene (Fig. 7F, blue line) has the same absorption maximum as that of all-trans-lycopene (Fig. 7F, black line), we believe this new peak represents 5-cis apo-10′-lycopenal formed from 5-cis-lycopene by cleavage at its 9′,10′-double bond. There are two possible cleavage sites in the lycopene molecule, at the 9,10-double bond or the 9′,10′-double bond (Fig. 1). The formation of 13-cis-apo-10′-lycopenal with its characteristic cis peak (Fig. 7) strongly suggests that CMO2 cleaves 13-cis-lycopene at its 9′,10′-double bond. However, in terms of the all-trans- and 5-cis-isomers, both have identical visible spectra, and the 5-cis-isomer with its terminal cis double bond does not have a characteristic cis peak (Fig. 7). Thus, we cannot rule out the possibility that this new peak represents all-trans-apo-10′-lycopenal from 5-cis-lycopene if the CMO2 cleaves 5-cis-lycopene at its 9,10-double bond (Fig. 1). In addition, because of significant isomerization of lycopene and apo-lycopenals, we consider that the substrate is a mixture of 5-cis:5-trans- and/or 5-trans:13-cis-lycopene and/or other isomers (e.g. 9-cis-isomers). Because of the difficulty in controlling isomerization of lycopene (even in the dark), we cannot rule in/out that the mixed lycopene isomers are cleaved to 5-cis,13-cis-apo-10′-lycopenal, and the latter isomerizes to a mixture of 5-trans- and 5-cis-,13-cis-isomers.

FIGURE 7. HPLC profile of the cleavage products of lycopene by ferret CMO2 enzyme.

The assays were carried out using the homogenates from CMO2 baculovirus-infected cells and incubated with either all-trans-lycopene (97%) (A), or 5-cis-lycopene (38%) (B), or 13-cis-lycopene (29%) (C ) at 37 °C for 60 min. The cleavage products extracted from the incubation mixture were separated by reverse phase HPLC using a C30 column as described under “Experimental Procedures.” D, the HPLC pattern of an authentic apo-10′-lycopenal standard matches exactly both the retention time (B, peak 1 and E) and the absorption spectrum of the product from 5-cis-lycopene. E, spectral analysis of the cleavage products of lycopene isomers. The absorption spectrum of the apo-10′-lycopenal standard (black line, peak 1 from D) compared with peak 1 (blue line, the reaction product in B) and peak 2 (red line, the reaction product in C ) extracted from the incubation of the homogenates of insect cells expressing ferret CMO2 with lycopene isomers. F, spectra of lycopene isomers (black line, all-trans-lycopene; blue line, 5-cis-lycopene; and red line, 13-cis-lycopene). The procedures for the incubation, extraction, and HPLC analysis were as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

To further demonstrate that CMO2 preferentially cleaves cis-isomers of lycopene, we used HPLC-purified 13-cis-lycopene isomer as a substrate in the incubation. We found that the 13-cis-lycopene purified by HPLC isomerizes rapidly to a mixture of all-trans and 5-cis-isomers, and only 29% remain as the 13-cis-isomer before the incubation. After the incubation with this mixture of lycopene (containing 29% as 13-cis-lycopene) as the substrate, there was a new metabolite derived from lycopene (Fig. 7C, peak 2), identified by HPLC analysis, in addition to the peak when the incubation was carried out with 5-cis-lycopene as the substrate (Fig. 7B). This new compound had a retention time of 11.6 min, a 0.4-min delay compared with the retention time of the apo-10′-lycopenal standard (Fig. 7D). This new peak had almost the same absorption maximum (λmax = 464 nm; Fig. 7E, red line) as the apo-10′-lycopenal standard (λmax = 462 nm; Fig. 7E, black line,) but was shifted 2 nm to longer wavelengths. This wavelength shift suggests that the peak contains the 13-cis-isomer of apo-10′-lycopenal, a finding substantiated by an additional absorption peak at 348 nm representing a cis peak, as is present in the parent compound, 13-cis-lycopene (Fig. 7F, red line). Because of the rapid isomerization of cis-lycopene in the incubation mixture, we also detected 5-cis-apo-10′-lycopenal after the incubation with 13-cis-lycopene (Fig. 7C). These same results, regarding the cleavage of cis-lycopene isomers, were obtained using the homogenate of COS-1 cells transfected with ferret CMO2 (data not shown). No enzymatic activity was detected in two control incubations done with uninfected insect cell homogenates or without cell homogenates (data not shown).

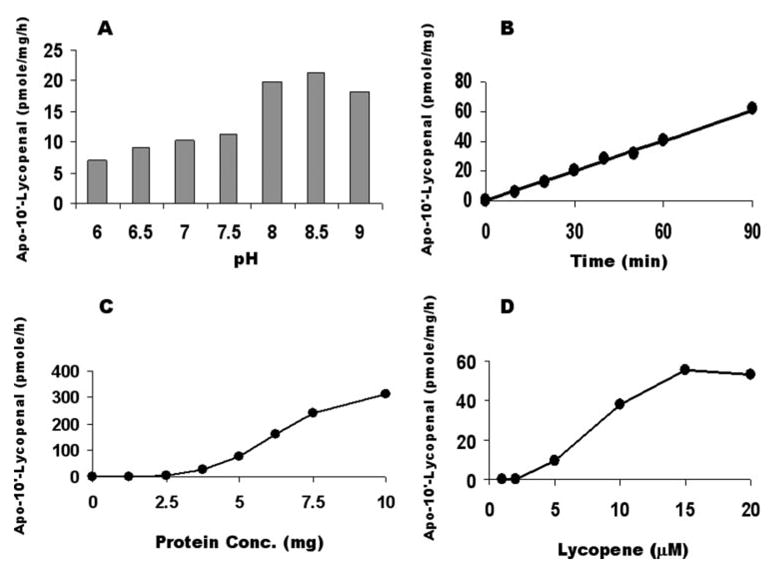

We then carried out a kinetic study using the lycopene mixture containing 15–20% as cis-isomers and 80–85% all-trans-lycopene as the substrate. Similar to the pH optimum of β-carotene, the production of apo-10′-lycopenal from cis-lycopene was also pH-dependent with the pH optimum occurring between 8.0 and 8.5 (Fig. 8A). The production of apo-10′-lycopenal was linear for 90 min (Fig. 8B). The enzyme concentration of ferret CMO2 varied between 0 and 10 mg of protein/ml, and the production of apo-10′-lycopenal is shown in Fig. 8C. The formation of apo-10′-lycopenal from lycopene was linear up to 7.5 mg/ml. Only a slight increase in apo-10′-lycopenal was achieved by increasing the protein concentration up to 10 mg/ml. The effect of lycopene concentration on the production of apo-10′-lycopenal from lycopene was linear up to 5 μM and increased slightly at 20 μM (Fig. 8D). Although we cannot calculate Km and Vmax values of the ferret CMO2 with mixed lycopene isomers as substrate, we estimate the Km and Vmax values were much lower than that of β-carotene.

FIGURE 8. Effects of pH, time, protein, and substrate concentrations on the production of apo-10′-lycopenal from lycopene (20% as cis-isomers) with ferret CMO2.

A, the reaction as a function of pH was conducted with homogenates of insect cells expressing ferret CMO2 with 5 μMlycopene. B, the time course of the reaction was conducted with homogenates of insect cells expressing ferret CMO2 with 5 μM lycopene for various time points. C, the reaction as a function of protein concentration was conducted with various protein concentrations of insect cells expressing ferret CMO2 with 5 μM lycopene. D, the reaction as a function of substrate concentration was conducted with homogenates of insect cells expressing ferret CMO2 with various lycopene concentrations. The enzyme reaction was conducted in a volume of 1 ml of assay buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM KCl, 10 μM Fe2SO2, 3 mM NAD, 0.3 mM DTT, and the 6 mg of protein of insect cell homogenates expressing ferret CMO2 at 37 °C for 60 min, unless indicated. The procedures for the incubation, extraction, and HPLC analysis were as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The data are the average of two independent experiments. The variation in the data between the two experiments was less than 9% of the data average.

The Formation of Apo-10′-lycopenol from Lycopene Supplementation in Ferret Lungs

Because ferrets accumulate a significant amount of cis-isomers of lycopene in the lung and stomach after a 9-week supplementation with all-trans-lycopene (19, 20), we analyzed the lung tissue of lycopene-fed ferrets for possible metabolites of lycopene. Fig. 9 shows the HPLC of lycopene isomers and lycopene metabolites in the lungs of the ferrets after all-trans-lycopene supplementation. Although ferrets were given all-trans-lycopene, cis-isomers of lycopene accounted for more than 50% of total lycopene in the lungs of ferrets and 5-cis was the predominant form among the cis-isomers (Fig. 9C). Several metabolites of lycopene were detected in the lung tissue of ferrets supplemented with lycopene (Fig. 9C). Among them, the characteristics of the peak with a retention time of 10.2 min (Fig. 9C, peak 1, which was extracted from the lung tissue of ferret) matched that (retention time = 10.2 min) of the apo-10′-lycopenol standard (Fig. 9A). This was also confirmed by matching the retention time of 10.2 min when the standard apo-10′-lycopenol was added into the sample (data not shown). Furthermore, the absorption spectrum of this peak (Fig. 9D, pale line) exactly matched that of the apo-10′-lycopenol standard (Fig. 9D, bold line). We did not detect any other carotenoids or metabolites in the ferrets given placebo supplementation (Fig. 9B).

FIGURE 9. HPLC of lycopene metabolites in the lungs of ferrets after 9 weeks of supplementation with lycopene.

A, HPLC pattern of standard apo-10′-lycopenol. B, HPLC pattern of ferret lung tissue extract after supplementation with placebo. C, HPLC pattern of ferret lung tissue extract after supplementation with lyco-pene. D, spectral analysis of the metabolic product (1st peak) of lycopene in the lung of ferret. The absorption spectrum of an apo-10′-lycopenol standard (boldface line) matched exactly that of the unknown compound (C, peak 1, pale line) extracted from ferret lung tissue after supplementation with lycopene. The peak identifications are as follows: 1, apo-10′-lycopenol; 2, echinenone (internal standard); 3, 13-cis-lycopene; 4, 9-cis-lycopene; 5, all-trans-lycopene; and 6, 5-cis-lycopene. The procedures for the animal experiment, tissue extraction, and HPLC analysis were as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

We further quantified apo-10′-lycopenol in the lung tissue. The mean concentration of apo-10′-lycopenol in the lungs of ferrets supplemented with lycopene was 8 ± 3 pmol/g wet weight lung tissue. Apo-10′-lycopenal and apo-10′-lycopenoic acid were not detected in the lung tissue of lycopene-supplemented ferrets, as apo-10′-lycopenal, the primary cleavage product (Fig. 1), might be an intermediate compound that could be either reduced to apo-10′-lycopenol or oxidized to apo-10′-lycopenoic acid and be present below our HPLC detection limits. To confirm this hypothesis, the incubation mixtures containing 5 mg of post-nuclear fraction of ferret liver homogenates with or without added cofactors (3 mM NAD+ or 3 mM NADH) were pre-incubated at 37 °C for 5 min, and then the reactions were initiated by adding apo-10′-lycopenal as substrate at the indicated concentrations (2 and 10 μM, see Table 1). We have observed that apo-10′-lycopenal was converted into apo-10′-lycopenoic acid in the presence of NAD+ as cofactor (Table 1). In the presence of NADH, apo-10′-lycopenal was converted into both apo-10′-lycopenol and apo-10′-lycopenoic acid (Table 1) in the incubation mixture of post-nuclear fraction of ferret liver.

TABLE 1. Effect of co-factors on the conversion of apo-10′-lycopenal into apo-10′-lycopenoic acid and apo-10′-lycopenol by ferret liver homogenates in vitro.

The incubation of apo-10′-lycopenal with the post-nuclear fraction of ferret liver with or without adding cofactors was carried out as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The incubation mixtures were extracted, dried, dissolved in 100 μl of ethanol, and subjected to analysis by HPLC, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Data are means ± S.D. from three independent determinations. ND indicates not detected.

| Substrate | Apo-10′-lycopenoic acid | Apo-10′-lycopenol |

|---|---|---|

| pmol/mg/h | ||

| Apo-10′-lycopenal (2 μM) | ||

| No cofactor | 0.5 ± 0.1 | ND |

| +NAD+ (μ mM) | 7.7 ± 0.1 | ND |

| +NADH (μ mM) | ND | 1.5 ± 0.2 |

|

| ||

| Apo-10′-lycopenal (10 μM) | ||

| No cofactor | 3.1 ± 0.2 | ND |

| +NAD− (μ mM) | 54.8 ± 2.3 | ND |

| +NADH (μ mM) | 14.8 ± 0.4 | 10.1 ± 0.7 |

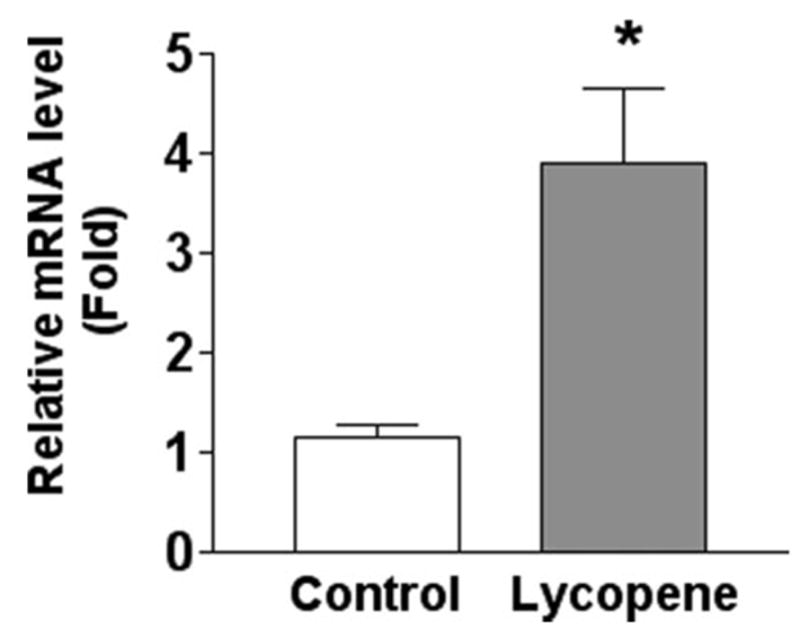

To determine whether lycopene supplementation can regulate CMO2 expression in the ferrets, we examined expression of CMO2 in the lungs of ferrets with or without lycopene supplementation. The expression of CMO2 mRNA in the lungs of ferrets was up-regulated 4-fold by lycopene supplementation, compared with ferrets not exposed to lycopene (Fig. 10). We were not able to detect the CMO2 protein in the lungs of ferrets with or without lycopene supplementation (data not shown).

FIGURE 10. Expression of CMO2 in the lungs of ferrets after lycopene supplementation for 9 weeks.

The relative levels (means ± S.D.) of CMO2 mRNA in lungs of ferrets were determined by real time PCR using β-actin levels as a reference gene. The procedures for the animal experiment, lung mRNA extraction, and real time PCR method are described under “Experimental Procedures.” Six ferrets were in each treatment group (Control, no treatment; Lycopene, lycopene-supplemented). * indicates significantly different at p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Our identification of the ferret CMO2 as the homologue of human CMO2 was based on the following: 1) A higher amino acid sequence homology with a well conserved CMO family signature sequence between ferret CMO2 and human CMO2 (82% homology), existed as compared with mouse CMO2 (77% homology); 2) expression of CMO2 in both COS-1 cells and baculovirus system generates a protein band with the predicted molecular mass of 60 kDa, which is recognized by a polyclonal antibody against ferret CMO2; 3) the recombinant CMO2 can cleave β-carotene specifically at its 9′,10′-double bond to produce β-apo-10′-carotenal; 4) iron is an essential co-factor for the reaction as well as the existence of the four conserved histidines and a glutamate residue, which have been demonstrated as putative iron-binding residues in all family members (10) in the ferret CMO2; and 5) CMO2 mRNA is expressed ubiquitously in ferret tissues with relatively higher expression in liver and testes, similar to previous reports in mice (15).

The observation that expression of CMO2 in lycopene-synthesizing and -accumulating E. coli strains exhibits a color shift, suggestive of a cleavage reaction (15), raises the question of whether CMO2 can catalyze the excentric cleavage of lycopene at the 9′,10′-double bond, forming apo-10′-lycopenal. In this study, we first confirmed that ferret CMO2 expressed in COS-1 cells cleaves both β-carotene and lycopene, and we then conducted kinetic studies using the ferret CMO2 expressed in SF9 insect cells. We demonstrate for the first time that the recombinant ferret CMO2 catalyzes the excentric cleavage of all-trans-β-carotene and cis-lycopene isomers effectively but not all-trans-lycopene at the 9′,10′-double bond. The mechanism whereby ferret CMO2 preferentially cleaves the 5-cis- and 13-cis-isomers of lycopene into apo-10′-lycopenal but not all-trans-lycopene is currently unknown. It has been reported that CMO1 catalyzes the cleavage of β-carotene and β-cryptoxan-thin at the central carbon 15,15′-double bond but cleaves lyco-pene with low activity (7) or no activity (9). These investigators suggested that at least one unsubstituted β-ionone ring in the substrate is imperative for cleavage of the central carbon 15,15′-double bond. Therefore, one possible explanation for our observation is that the chemical structure of cis-isomers of lycopene could mimic the ring structure of the β-carotene molecule and fit into the substrate-enzyme binding pocket. This hypothesis warrants further investigation. Recently, it has been reported that apocarote-noid 15,15′-oxygenase from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 functions as an isomerase, i.e. on binding, three consecutive double bonds of all-trans-(3R)-3-hydroxy-8′-apo-β-carotenol changed from a straight all-trans to a cranked cis-transcis (13,14 –13′,14′-dicis) conformation, and then the remaining trans bond is located at the dioxygen-ligated Fe2+ hold by four histidines and cleaved by oxygen (11). However, in our study, we barely detect any cleavage product when all-trans-lycopene was used as a substrate. It is therefore unlikely that the CMO2 functions as an isomerase as the apocarotenoid 15,15′-oxygenase does.

In this study, we provide information on the biochemical characterization of ferret CMO2 regarding the cleavage of β-carotene and lycopene into β-apo-10′-carotenal and apo-10′-lycopenal, respectively. The cleavage of these carotenoids by the ferret CMO2 occurs in a pH, incubation time, protein dose-, and substrate dose-dependent manner. The optimum pH for CMO2 is 8.5 regardless of the substrate as β-carotene or cis-lycopene, and this differs from the optimum pH (7.7) for the activity of CMO1, a central cleavage enzyme for carotenoids (9). The different optimum pH between these two carotenoid cleavage enzymes may indicate the different role of two pathways of carotenoid metabolism or different functions of various pathophysiological conditions, which need further investigation. However, similar to the CMO1, we found that the cleavage activity of ferret CMO2 for both β-carotene and lycopene was iron-dependent, indicating that iron is an essential cofactor for the enzymatic cleavage activity of carotenoids. This is supported by the existence of four conserved histidines residues in the ferret CMO2. These data are in agreement with the recent demonstration that these conserved histidines are putative iron-binding residues for iron coordination in apocarotenoid 15,15′-oxygenase (11) and CMO1 (10), and support the notion that the entire superfamily of oxygenases shares a common structure (10).

It should be pointed out that we calculated a Km of 3.5 μM for all-trans-β-carotene based on the CMO2 expressed in SF9 cells, in which the CMO2 was only 3–5% of total protein in the cell extracts. In addition, we cannot calculate the kinetic constants of CMO2 for lycopene because it is difficult to control the auto-isomerization of lycopene (e.g. 13-cis-lycopene was rapidly isomerized into to 5-cis-lycopene and all-trans-lycopene after we collected 13-cis-lycopene as 100% by using HPLC), and mixed isomers of lycopene were therefore used as the substrate. However, because the lycopene substrate contains only ~20% as cis-isomers, which was confirmed by HPLC analysis, and the ferret CMO2 would not cleave all-trans-lycopene, we speculate that the Km value for cis-lycopene is actually much lower than that of the lycopene isomer mixture. This indicates that cis-lycopene may act as a better substrate than all-trans-β-carotene for the ferret CMO2. Our finding that ferret CMO2 preferentially cleaves cis-lycopene rather than all-trans-lycopene may provide new insight into the biochemistry and physiology of CMO2 because cis-lycopene is a predominant form in humans and animals.

The in vivo evidence for the existence of an excentric cleavage pathway for β-carotene in mammalian tissues has been provided in earlier investigations by the identification of apo-10′- and 12′-carotenals from β-carotene in the intestines of chickens (24) and ferrets (25, 26). A number of studies have shown that apo-carotenoids produced from the excentric cleavage of β-carotene can possess either more or less biological activity than β-carotene or have entirely different functions, in terms of either beneficial or detrimental effects to human health (1). It has been reported that apo-carotenoids, such as apo-10′-, 12′-, and 14′-carotenoids, can inhibit the growth of HL-60 cells (27) and breast cancer cells (28) and stimulate the differentiation of U937 leukemia cells (29). We have observed that β-apo-14′-carotenoic acid completely reversed the down-regulation of RARβ by smoke-borne carcinogens in normal bronchial epithelial cells and transactivated the RARβ promoter via metabolism to the potent RAR ligand, all-trans-retinoic acid (30). Recently, we have observed that apo-10′-lycopenoic acid exerts a growth inhibitory effect on lung cancer cell lines, in a dose-dependent manner (31). In this study, we first provide the in vivo evidence for lycopene cleavage by identifying apo-10′-lycopenol in the lungs of ferrets after lycopene supplementation. Interestingly, we detected a significant amount of cis-isomers of lycopene in the lungs and stomach of ferrets, particularly the 5-cis-lycopene, after supplementation with all-trans-lycopene. Although the formation of apo-10′-lycopenol as a major metabolite of lycopene in the lungs of ferrets after lycopene supplementation is demonstrated, we cannot rule out the formation of other metabolites (e.g. compounds appearing between retention time 10 and 13 min in the HPLC profile) arising from lycopene. In addition, we did not detect apo-10′-lycopenal or apo-10′-lycopenoic acid in the lung tissues of lycopene-supplemented ferrets. It is likely that apo-10′-lycopenal is a short-lived intermediate compound and can be reduced to its alcohol form in vivo, and apo-10′-lycopenoic acid may be present at too low a concentration to be detected in our HPLC system. This was supported by our further demonstrations that the incubation of apo-10′-lycopenal with the post-nuclear fraction of hepatic tissue of ferrets resulted in both apo-10′-carotenol and apo-10′-lycopenoic acid depending upon the presence of either NAD+ or NADH (Table 1). In the presence of NADH, apo-10′-lycopenal was converted to both alcohol form and acid form (Table 1). The latter could be due to the consumption of NADH for the reduction reaction, which makes NAD+ available for the oxidation of apo-10′-lycopenal.

In this present study, similar to the observations from mice (15) and humans (32), we detected CMO2 mRNA in various organs, particularly in the prostate, lung, and colon of ferrets, which has implications for the potential biological activity of lycopene (or its metabolites) in the prevention of cancer in these organs, as suggested in a number of previous epidemiological studies (33). High expression of CMO2 in liver and testis may be related to hepatic metabolism of lycopene or spermatogenesis. These observations highlight the need for greater knowledge regarding lycopene metabolism by CMO2 and biological functions of lycopene metabolites in the specific organs.

In this study, we demonstrate that lycopene supplementation can up-regulate the expression of CMO2 in the lungs of ferrets, as compared with the nonsupplemented ferrets. Although the mechanism(s) as to how lycopene regulates the expression of CMO2 is unclear, it has been reported that the peroxisome proliferator-response element, which is located in the promoter region of the mouse CMO1, allows peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ activators to regulate the expression of the gene via the heterodimerization of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ with the retinoid X receptor-α receptor (34). The investigation as to whether apo-10′-lycopenoic acid could transactivate the gene containing retinoic acid-response element/peroxisome proliferator-response element is underway in this laboratory. Further characterization and the biological function(s) of lycopene oxidative metabolites and the regulation of CMO2 will potentially provide invaluable insights into the mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of lycopene to humans.

Footnotes

The nucleotide sequence(s) reported in this paper has been submitted to the Gen-BankTM/EBI Data Bank with accession number(s) AY527150.

The abbreviations used are: CMO1, carotene 15,15′-monooxygenase; CMO2, carotene 9′,10′-monooxygenase; HPLC, high performance liquid chromatography; RACE, rapid amplification of cDNA ends; RAR, retinoic acid receptor; HA, hemagglutinin; DTT, dithiothreitol; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

References

- 1.Wang XD. In: Carotenoids in Health and Disease. Krinsky NI, Mayne ST, Sies H, editors. Marcel Dekker; New York: 2004. pp. 313–335. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodman DS, Huang HS. Science. 1965;149:879–880. doi: 10.1126/science.149.3686.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olson JA, Hayaishi O. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1965;54:1364–1370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.54.5.1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wyss A, Wirtz G, Woggon W, Brugger R, Wyss M, Friedlein A, Bachmann H, Hunziker W. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;271:334–336. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von Lintig J, Wyss A. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;385:47–52. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leuenberger MG, Engeloch-Jarret C, Woggon WD. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2001;40:2613–2617. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010716)40:14<2613::AID-ANIE2613>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Redmond TM, Gentleman S, Duncan T, Yu S, Wiggert B, Gantt E, Cunningham FX., Jr J Biol Chem. 2001;276:6560–6565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paik J, During A, Harrison EH, Mendelsohn CL, Lai K, Blaner WS. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32160–32168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010086200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindqvist A, Andersson S. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23942–23948. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202756200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poliakov E, Gentleman S, Cunningham FX, Jr, Miller-Ihli NJ, Redmond TM. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:29217–29223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500409200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kloer DP, Ruch S, Al-Babili S, Beyer P, Schulz GE. Science. 2005;308:267–269. doi: 10.1126/science.1108965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang XD, Tang GW, Fox JG, Krinsky NI, Russell RM. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1991;285:8–16. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90322-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang GW, Wang XD, Russell RM, Krinsky NI. Biochemistry. 1991;30:9829–9834. doi: 10.1021/bi00105a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang XD, Russell RM, Liu C, Stickel F, Smith DE, Krinsky NI. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:26490–26498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiefer C, Hessel S, Lampert JM, Vogt K, Lederer MO, Breithaupt DE, von Lintig J. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:14110–14116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011510200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamel CP, Tsilou E, Pfeffer BA, Hooks JJ, Detrick B, Redmond TM. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:15751–15757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwartz SH, Tan BC, Gage DA, Zeevaart JA, McCarty DR. Science. 1997;276:1872–1874. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5320.1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruch S, Beyer P, Ernst H, Al-Babili S. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:1015–1024. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu C, Lian F, Smith DE, Russell RM, Wang XD. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3138–3144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu C, Russell RM, Wang XD. J Nutr. 2006;136:106–111. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang XD. In: Carotenoids and Retinoids. Packer L, Kraemer K, Obermuller-Jevic U, Sies H, editors. AOCS Press; Champaign, IL: 2005. pp. 168–181. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boileau AC, Merchen NR, Wasson K, Atkinson CA, Erdman JW., Jr J Nutr. 1999;129:1176–1181. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.6.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang XD, Liu C, Bronson RT, Smith DE, Krinsky NI, Russell RM. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:60–66. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharma RV, Mathur SN, Dmitrovskii AA, Das RC, Ganguly J. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976;486:183–194. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(77)90083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang XD, Krinsky NI, Marini RP, Tang G, Yu J, Hurley R, Fox JG, Russell RM. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:G480–G486. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1992.263.4.G480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang XD, Marini RP, Hebuterne X, Fox JG, Krinsky NI, Russell RM. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:719–726. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90444-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suzuki T, Matsui M, Murayama A. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol. 1995;41:575–585. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.41.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tibaduiza EC, Fleet JC, Russell RM, Krinsky NI. J Nutr. 2002;132:1368–1375. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.6.1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winum JY, Kamal M, Defacque H, Commes T, Chavis C, Lucas M, Marti J, Montero JL. Farmaco (Rome) 1997;52:39–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prakash P, Liu C, Hu KQ, Krinsky NI, Russell RM, Wang XD. J Nutr. 2004;134:667–673. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.3.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lian F, Russell RM, Ernst H, Wang XD. FASEB J. 2005;19:1459. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindqvist A, He YG, Andersson S. J Histochem Cytochem. 2005;53:1403–1412. doi: 10.1369/jhc.5A6705.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giovannucci E. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2002;227:852–859. doi: 10.1177/153537020222701003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boulanger A, McLemore P, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Yu SS, Gentleman S, Redmond TM. FASEB J. 2003;17:1304–1306. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0690fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]