Abstract

Immunity to Leishmania donovani is associated with an interleukin (IL)-12 driven T helper 1 (Th1) response. In addition, the ability to respond to chemotherapy with sodium stibogluconate (SSG) requires a fully competent immune response and both Th1 and Th2 responses have been shown to positively influence the outcome of drug treatment. In the present study, the influence of IL-18, which can modulate both interferon (IFN)-γ and IL-4 production, on the outcome of primary L. donovani infection and SSG therapy following infection was assessed using BALB/c IL-18-deficient and wild type mice. IL-18 deficiency was associated with an increased susceptibility to L. donovani infection, evident by day 40 post infection, resulting in higher parasite burdens in the spleen, liver, and bone marrow compared with wild type control animals. Infected IL-18-deficient mice had significantly lower splenocyte concanavalin A (ConA) induced IFN-γ production as well as lower serum IL-12 and IFN-γ levels, indicating a reduced Th1 response. However, drug treatment was equally effective in both mouse strains and restored serum IL-12 and IFN-γ levels, and IFN-γ production by ConA stimulated splenocytes of IL-18-deficient mice, to levels equivalent to similarly treated wild type mice.

Keywords: Leishmania donovani, IL-18, sodium stibogluconate

Introduction

Interleukin (IL)-18 is produced by a variety of cells including macrophages, dendritic cells and Kupffer cells.1,2 IL-18 production was originally associated with induction of T helper (Th)1 responses because it can induce IFN (interferon)-γ production, especially when acting in concert with IL-12. However, under certain conditions IL-18 can also regulate Th2 responses because it has been shown to modulate the production of cytokines such as IL-4, IL-13 and IL-10.1,3,4

IL-18 has been shown to have a protective role against infections where IFN-γ production is known to be important. For example, treatment of mice with IL-18 deficiency was associated with protection against infection with Salmonella typhimurium, Cryptococcus neoformans and Toxoplasma gondii.5–7 Introduction of IL-18 deficiency into a mouse strain that normally controls L. major infection rendered it highly susceptible to infection.8 This susceptibility was associated with a significant decrease in IFN-γ production and an increase in the Th2-associated cytokine, IL-4, compared to corresponding control mice.8 However, IL-18 can also have an exacerbatory role; for example, IL-18-deficient mice recovered more rapidly from influenza virus infection than wild-type controls. This effect was not mediated by a decrease in IFN-γ production because similar levels were present in the lungs of wild type and IL-18-deficient mice, and in T cells and natural killer cells isolated from the lungs of both types of animals.9 It was therefore suggested that IL-18 was acting through an IFN-γ-independent mechanism.

In contrast, IL-18 can influence the outcome of infection through Th2 protective responses. For example, chronic infection with the gastrointestinal nematode Trichuris muris was mediated by IL-18 directly down-modulating IL-13 production.10 In addition, IL-18 is associated with susceptibility to Trichinella spiralis infection because IL-18-deficient mice expressed a resistant instead of a susceptible phenotype. It was demonstrated that this effect was mediated by inhibition of mastocytosis and production of the Th2 cytokines IL-13 and IL-10.10 Futhermore, IL-18 treatment of BALB/c mice infected with Leishmania major, where Th1 cells and IFN-γ production are important in protection, resulted in disease exacerbation and enhanced Th2 responses.11

Susceptibility to Leishmania donovani infection in humans involves the induction of both Th1 and Th2 responses but the ability to control infection is associated with a down-regulation in IL-10 production and an up-regulation in IFN-γ and IL-12 production.12 Studies using animal models have given similar results and indicate that resistance to infection requires an IL-12-driven Th1 or CD8+ T-cell response, leading to the production of IFN-γ and stimulation of infected macrophages, whereas over production of IL-10 results in disease exacerbation.12–14 Thus, the balance between Th1 and Th2 responses is important in controlling resistance and/or susceptibility to L. donovani infection. The host’s immune response is also important in the outcome of sodium stibogluconate (SSG) treatment in L. donovani. Clinical studies have shown that SSG is less effective in immunocompromised individuals and high relapse rates are common.15 Animal studies have demonstrated that successful treatment with SSG requires the presence of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and both Th1 and Th2 cytokines are required.16–19 As IL-18 influences both Th1 and Th2 responses and is produced by activated macrophages and Kupffer cells, the host cell for parasite, then it is highly likely that IL-18 may have a major influence on both the outcome of infection and SSG treatment in L. donovani.1 Therefore, in this study the importance of endogenous IL-18 in susceptibility to infection and the outcome of SSG drug treatment were assessed by comparing responses of BALB/c IL-18 deficient and wild type mice infected with L. donovani.

Materials and methods

Materials

SSG was obtained from Glaxo Wellcome (Uxbridge, UK). Capture and detection anticytokine antibodies, IL4, IL-10, IFN-γ and IL-12 standards and alkaline phosphatase conjugate were obtained from PharMingen and supplied by Insight Biotechnology (Wembley, UK). IL-18 was quantified using OPTEIA™ mouse IL-18 set obtained from PharMingen and supplied by Insight Biotechnology (Wembley, UK). All other reagents were of analytical grade.

Animals and parasites

Age- and sex-matched in-house in-bred IL-18-deficient mice BALB/c mice (20–25 g, in-house female) and their wild type counterparts, were used in this study.19 IL-18 gene-deficient mice were generated by gene targeting in a 129/Sv background. The mice were back-crossed for 10 generations with mice with a BALB/c background before breeding heterozygous mice (+/–) to produce three genotypes of IL-18 knockout mice, homozygous (–/–), heterozygous (+/–) and wild type (+/+) mice. IL-18–/– and IL-18+/+ mice were produced by breeding IL-18–/– and IL-18+/+ pairs, respectively, for use in experiments. Commercially obtained Golden Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) were used for maintenance of L. donovani strains (Harlan Olac, Bicester, UK). L. donovani strains 200016 and 200011 were used in the studies.20 Mice were infected on day 0 by intravenous injection (tail vein, no anaesthetic) with 1–2 × 107L. donovani amastigotes.21 Animal experiments were carried out in accordance with UK Home Office regulations.

In vivo studies

To compare the course of infection in IL-18-deficient mice and their wild type counterparts (n = 4 or 5 per treatment) were infected with L. donovani and killed on different days post infection. In drug studies infected mice were treated intravenously on days 14 and 15 with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, controls) or SSG solution (equivalent to a final dose of III mg Sbv/kg). In this case parasite burdens were determined on day 40 or day 44 post infection. Impression smears of the spleen and liver, and a smear of bone marrow, were made on to an individual glass microscope slide for each mouse at death. The slides were fixed in methanol for 30 s, stained in 10% aqueous Giemsa stain (BDH, VWR International Ltd, Poole, UK) for 20 min, and then allowed to air dry. The number of parasites present/1000 host nuclei for the spleen, liver and bone marrow for each sample was determined at ×1000 magnification. The Leishman Donovan unit (LDU) was calculated by multiplying the number of parasites present/1000 host nuclei by the organ weight (g) for the spleen and liver.

Specific antibody response of infected mice

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) were carried out to determine the end point titres of parasite specific immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) and IgG2a present in the serum, against an L. donovani soluble antigen (SAG). The SAG was prepared by freeze–thawing L. donovani promastigotes, suspended in PBS, three times using liquid nitrogen. SAG protein concentration (typically >1 mg/ml) was determined before storing in aliquots at −20°. Blood, collected from mice at death, was stored overnight or for 2–5 hr at 4°. Clotted blood was centrifuged at 7000 g for 10 min and the resulting serum collected and stored at −20° until serum antibody titres could be analysed. Microtitre plates were coated overnight at 4° with 100 µl of the L. donovani SAG antigen preparation (10 µg/ml) in coating buffer (PBS, pH 9). Plates were washed three times with wash buffer (PBS, pH 7·4, supplemented with 0·05% v/v Tween-20) and 100 µl of the appropriate serum sample (serially diluted from 1/100 in PBS, pH 7·4, supplemented with 0·05% v/v Tween-20) added to the appropriate wells of the plates. Plates were incubated for 1 hr at 37°, washed as above and 100 µl of 1/1000 dilution of the appropriate conjugate added/well [horseradish peroxidase anti-mouse IgG1, IgG2a conjugates (Binding Site, Birmingham, UK)]. Conjugates were diluted in conjugate buffer (1 : 3 v/v sheep serum: PBS, pH 7·4). Plates were incubated for a further hour at 37° before washing as above. 100 µl of substrate (250 µl of 6 mg/ml tetramethyl benzidine in dimethyl sulphoxide, 7 µl H2O2 made up to 25 ml with substrate buffer (1·36% w/v aqueous solution of sodium acetate, pH adjusted to 5·5 with solid citric acid) was added/well. Plates were incubated for 20 min at room temperature, the reaction was stopped by the addition of 50 µl/well of 10% v/v sulphuric acid and the absorbance at 450 nm determined. The end point was the last dilution that gave a positive response to compared to background levels to the SAG.

Cytokine production

Single-cell suspension of spleen cells, prepared from spleen samples collected at death, were incubated in vitro with medium alone (unstimulated controls), parasite antigen (12·5 µg/ml) or Concanavalin A (ConA, 5 µg/ml, stimulated cells) as described by Carter et al.22 The resulting cell supernatants were stored at −20° until assayed. IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, IL-18 and IFN-γ levels in cell supernatants, and serum IL-12 and IFN-γ levels, were determined by ELISA.22

Statistical analysis of data

Parasite data from in vivo experiments were analysed using a one-way anova (using log10 transformed LDU values for the spleen and liver data, and log10 transformed parasite numbers/1000 host cell nuclei for bone marrow data). Differences between treatments were then analysed using a Fisher’s PLSD test using the Statview® version 5.0.1 software package. Cytokine, nitrite, and antibody data were analysed using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test.

Results

IL-18 deficiency is related to increased susceptibility to L. donovani infection but is time dependent

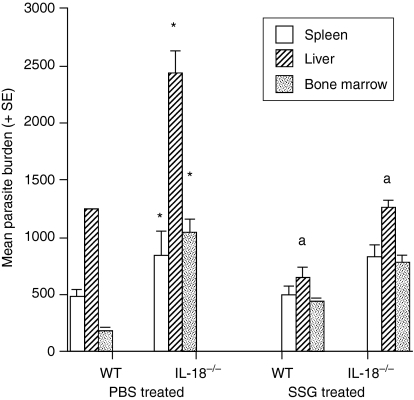

The inability to produce IL-18 had no significant difference on L. donovani parasite burdens in the spleen, liver or bone marrow on day 14 post infection because similar numbers of parasites were present in IL-18-deficient and wild type mice (data not shown). However, by day 40 post infection IL-18-deficient mice had significantly higher parasite numbers in all three sites compared to wild type controls (Fig. 1). This effect was apparent for both parasite strains used in studies (data for L. donovani strain 200016 only shown).

Figure 1.

The effect of SSG treatment on parasite spleen, liver, and bone marrow L. donovani parasite burdens of IL-18-deficient and wild type mice on day 40 post infection. Mice were infected with L. donovani strain 200016 and treated on days 14 and 15 postinfection with PBS (control) or SSG (III mg Sbv/kg/day). Results from one of two independent experiments are shown. *P < 0·05 compared to wild type control, aP < 0·05 SSG-treated compared to corresponding control.

Increased susceptibility of IL-18-deficient mice to L. donovani infection is related to a reduction in Th1 responses

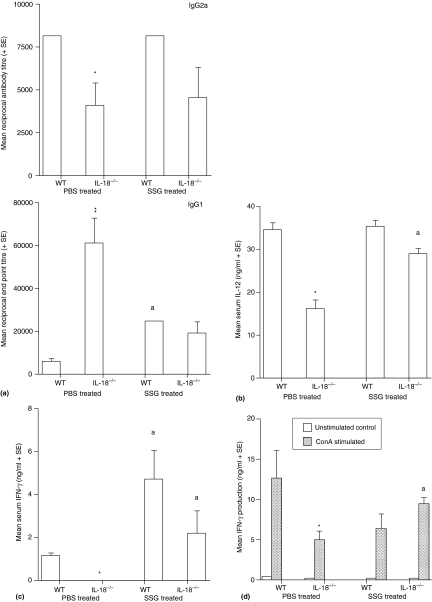

Parasite-specific IgG1 levels were significantly higher in IL-18-deficient mice on day 40 post infection compared to wild type values, whereas specific IgG2a levels were significantly lower (Fig. 2a). This indicates that IL-18 deficiency was related to a down-regulation in Th1 responses and a corresponding up-regulation in Th2 responses. IL-18-deficient mice also had significantly lower amounts of IL-12 (Fig. 2b) and IFN-γ (Fig. 2c) present in their serum on day 40 post infection compared to wild type controls. Stimulation with ConA resulted in a significant increase in IFN-γ production by splenocytes from wild type and IL-18-deficient mice compared to corresponding unstimulated control values, but significantly lower amounts were produced by spleen cells from IL-18-deficient animals (Fig. 2d). Stimulation with specific antigen had no effect on IFN-γ production by splenocytes from wild type or IL-18-deficient mice compared to corresponding unstimulated control values (data not shown). There was no consistent difference in nitrite production by unstimulated and ConA splenocytes from wild type and IL-18-deficient mice (data not shown). Results from lymphocyte proliferation assays confirmed the genotype of IL-18-deficient mice because only splenocytes from wild type mice produced IL-18 (data not shown). Similar levels of IL-4 and IL-10 were produced by unstimulated and antigen or ConA stimulated splenocytes for both mouse strains (data not shown). IL-18 deficiency did not influence cytokine production in uninfected mice because similar amounts of IL-12 were present in the serum for both mouse strains, and similar levels of IFN-γ were present in the serum and in cell supernatants from in vitro proliferation assays, for both mouse strains (data not shown). This is in agreement with previous results obtained by Wei (published and unpublished data) and Helmsby et al. for uninfected IL-18-deficient mice and their wild type counterparts.8,21

Figure 2.

Parasite-specific IgG1 and IgG2a levels (a), serum IL-12 levels (b), and serum IFN-γ levels (c), and IFN-γ levels by in vitro stimulated splenocytes (d) on day 40 post infection for wild type and IL-18-deficient mice, infected with L. donovani strain 200016. Mice were treated on days 14 and 15 post infection with PBS (control) or SSG (III mg Sbv/kg/day). Results from one of two independent experiments are shown. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01 compared to wild type control, aP < 0·05 SSG-treated compared to corresponding control.

IL-18 deficiency does not affect the outcome of SSG treatment

Treatment with SSG was equally active in wild type and IL-18-deficient animals, resulting in similar significant suppression in liver parasite burdens compared to relevant control values (Fig. 1, mean percentage suppression ± SE, wild type mice, 41 ± 9; IL-18-deficient mice 41 ± 8).

Chemotherapy resulted in a significant increase in specific IgG1 levels in wild type mice, whereas a decrease in IgG1 titres was obtained for IL-18 deficient mice, compared to their respective controls (Fig. 2a). Specific IgG2a levels were similar in control and drug-treated mice for both mouse strains (Fig. 2a).

Treatment with SSG significantly enhanced serum levels of IL-12 (Fig. 2b) and production of IFN-γ by ConA stimulated splenocytes (Fig. 2d) for IL-18-deficient mice compared to control values, but had no significant effect on wild type responses. Similar, elevated, serum IFN-γ levels, were present in drug treated mice for both mouse strains compared to their respective control (Fig. 2c). Drug treatment had no significant effect on the amount of IL-4 or IL-10 produced by antigen or ConA stimulated spleen cells for either strain (data not shown).

Discussion

The results of this study show that IL-18 deficiency does not affect initial susceptibility to L. donovani infection as similar parasite burdens were present on day 14 post infection in wild type and IL-18-deficient animals. However, delaying assessment of parasite burdens until day 40–44 post infection showed that IL-18 deficiency was associated with significantly higher parasite burdens compared to wild-type mice, regardless of the strain of L. donovani used to infect mice. At this later time point, IL-18-deficient animals had significantly lower concentrations of IL-12 and IFN-γ in their serum and significantly lower levels of IFN-γ were produced by ConA-stimulated splenocytes. Additionally, infection resulted in significantly lower levels of parasite-specific IgG2a antibodies but higher levels of IgG1 in IL-18-deficient mice compared to wild type controls. It is possible that these differences in immunological parameters could be caused by the higher parasite burdens in IL-18-deficient mice, rather than as a consequence of the absence of IL-18. However, in previous studies we have found that higher parasite burdens do not necessarily correlate with differences in immune responses, for example, control and drug treated mice can have similar immune responses despite substantial differences in parasite burdens (data not shown). The ability to control L. donovani infection is related to the induction of a predominant Th1 response and stimulation of leishmanicidal mechanisms of infected macrophages and both IL-12 and IFN-γ are important in susceptibility to infection because mice deficient in either cytokine are more susceptible to L. donovani infection.18,23 Murray et al. have shown that C57BL/6 IL-18-deficient mice have significantly higher L. donovani parasite burdens compared to wild type mice at 2 and 4 weeks postinfection, but by week 8 IL-18-deficient mice had controlled their infection.24 In this study BALB/c IL-18-deficient mice did not have significantly higher parasite burdens compared to BALB/c wild type mice until day 40 post infection. C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice are both susceptible to L. donovani but C57BL/6 mice, unlike BALB/c mice, cure their infection, and this ability is associated with a greater ability to produce IFN-γ,16 perhaps indicating that the ability of IL-18 to regulate IFN-γ production occurs earlier in C57BL/6 compared to BALB/c mice infected with L. donovani. The mouse strain used also has a major effect on the role of IL-18 in L. major infection. IL-18-deficient 129xCD1 mice are more susceptible, IL-18-deficient BALB/c mice are more resistant, and IL-18-deficient C57BL/6 are equally susceptible, to L. major infection compared to their corresponding wild-type control.19 T cells from IL-18-deficient BALB/c mice infected with L. major produced significantly lower amounts of IFN-γ and IL-4 after stimulation compared to wild type controls perhaps indicating that the resistance to L. major infection in IL-18-deficient mice was associated with a down regulation in Th2 responses rather than an up regulation in Th1 responses.19 IL-18 is known to down regulate IL-13 production and IL-13 is known to be important in controlling susceptibility to L. major infection.10,25 Similar to the results presented in this study, IL-18 deficiency in L. major did not affect initial susceptibility to infection since a difference in susceptibility was not apparent until 6 weeks post infection.

IL-18 deficiency did not affect the outcome of SSG drug therapy, as the same SSG treatment regimen was equiactive (based on mean percentage suppression in liver parasite burdens) in IL-18-deficient and wild type mice. Murray et al. also found that AmBisome® was highly effective in IL-18-deficient C57BL/617. In this study SSG treatment of IL-18-deficient mice was associated with an increase in serum IL-12 levels compared to corresponding control values. IL-12 is important in regulating the outcome of SSG drug treatment because IL-12-deficient mice do not respond to drug treatment and treatment with IL-12 increases the efficacy of SSG. IL-12 can increase the efficacy of SSG via its ability to induce IFN-γ production and via an IFN-γ-independent pathway.23 The former may be important here as significantly lower amounts of IFN-γ were produced by splenocytes from IL-18-deficient animals compared to corresponding controls. It is possible that the presence of killed parasites as a result of SSG treatment could have boosted host immune responses or that SSG could have made cells more responsive to lower doses of IFN-γ and boost Th1 responses because antimonial drug treatment can up-regulate interferon-γ receptor 1 on uninfected and infected cells.26 In addition antimonial drug treatment can induce superoxide, nitric oxide, and hydrogen peroxide in macrophages which would boost protective macrophage immune responses and indirectly modulate Th1 responses.27 However, this effect would have to be more effective in IL-18 deficient mice, perhaps as a result of their immunodeficiency.

The results of this study show that IL-18, through its ability to regulate Th1 responses, is involved in protection against L. donovani. However, like Murray et al. we would concur that although IL-18 mediates in protection against L. donovani infection, its presence is not essential.24 Clinical studies also indicate that IL-18 has a role in L. donovani infection because visceral leishmaniasis patients have a reduced ability to produce IL-18 compared to healthy controls.28

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge helpful comments from Professor J. Alexander, Professor P. Kaye and Dr S. Stager on this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- Con A

concanavalin A

- IFN

interferon

- IL

interleukin

- SAG

soluble antigen

- SSG

sodium stibogluconate

- Th

T helper

References

- 1.Dinarello C, Fantuzzi G. Interleukin 18 and host defence. J Infectious Dis. 2003;187:S370–S384. doi: 10.1086/374751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsutsui H, Adachi K, Seki E, Nakanishi K. Cytokine-induced inflammatory liver injuries. Current Mol Med. 2003;3:545–59. doi: 10.2174/1566524033479618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helmby H, Grencis RK. IL-18 regulates intestinal mastocytosis and Th2 cytokine production independently of IFN-γ during Trichinella spiralis infection. J Immunol. 2002;169:2553–60. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.5.2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wei XQ, Leung BP, Arthur HM, McInnes IB, Liew FY. Reduced incidence and severity of collagen-induced arthritis in mice lacking IL-18. J Immunol. 2001;166:517–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai G, Kastelein R, Hunter CA. Interleukin-18 (IL-18) enhances innate IL-12-mediated resistance to Toxoplasma gondii. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6932–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.12.6932-6938.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawakami K, Qureshi MH, Zhang T, Okamura H, Kurimoto M, Saito A. IL-18 protects mice against pulmonary and disseminated infection with Cryptococcus neoformans by inducing IFN-gamma production. J Immunol. 1997;159:5528–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mastroeni P, Clare S, Khan S, Harrison JA, Hormaeche CE, Okamura H, Kurimoto M, Dougan G. Interleukin 18 contributes to host resistance and gamma interferon production in mice infected with virulent Salmonella typhimurium. Infect Immun. 1999;67:478–83. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.2.478-483.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei XQ, Leung BP, Niedbala W, et al. Altered immune responses and susceptibility to Leishmania major and Staphylococcus aureus infection in IL-18-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1999;163:2821–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Der Sluijs KF, Van Elden LJ, Arens R, et al. Enhanced viral clearance in interleukin-18 gene-deficient mice after pulmonary infection with influenza A virus. Immunology. 2005;114:112–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.02000.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helmby H, Takeda K, Akira S, Grencis RK. Interleukin (IL)-18 promotes the development of chronic gastrointestinal helminth infection by downregulating IL-13. J Exp Med. 2001;194:355–64. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.3.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu D, Trajkovic V, Hunter D, Leung BP, Schulz K, Gracie JA, McInnes IB, Liew FY. IL-18 induces the differentiation of Th1 or Th2 cells depending upon cytokine milieu and genetic background. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:3147–56. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200011)30:11<3147::AID-IMMU3147>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melby PC, Tabares A, Restrepo BI, Cardona AE, McGuff HS, Teale JM. Leishmania donovani. evolution and architecture of the splenic cellular immune response related to control of infection. Exp Parasitol. 2001;99:17–25. doi: 10.1006/expr.2001.4640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaye PM, Svensson M, Ato M, Maroof A, Polley R, Stager S, Zubairi S, Engwerda CR. The immunopathology of experimental visceral leishmaniasis. Immunol Rev. 2004;201:239–53. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lehmann J, Enssle KH, Lehmann I, Emmendorfer A, Lohmann-Matthes ML. The capacity to produce IFN-gamma rather than the presence of interleukin-4 determines the resistance and the degree of susceptibility to Leishmania donovani infection in mice. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2000;20:63–77. doi: 10.1089/107999000312748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moreno J, Canavate C, Chamizo C, Laguna F, Alvar J. HIV–Leishmania infantum co-infection: humoral and cellular immune responses to the parasite after chemotherapy. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94:328–32. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(00)90345-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alexander J, Carter KC, Al-Fasi N, Satoskar A, Brombacher F. Endogenous IL-4 is necessary for effective drug therapy against visceral leishmaniasis. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:2935–43. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200010)30:10<2935::AID-IMMU2935>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray HW, Oca MJ, Granger AM, Schreiber RD. Requirement for T cells and effect of lymphokines in successful chemotherapy for an intracellular infection. Experimental visceral leishmaniasis. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:1253–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI114009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murray HW, Montelibano C, Peterson R, Sypek JP. Interleukin-12 regulates the response to chemotherapy in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1497–502. doi: 10.1086/315890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei XQ, Niedbala W, Xu D, Luo ZX, Pollock KG, Brewer JM. Host genetic background determines whether IL-18 deficiency results in increased susceptibility or resistance to murine Leishmania major infection. Immunol Lett. 2004;94:35–7. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carter KC, Sundar S, Spickett C, Pereira OC, Mullen AB. The in vivo susceptibility of Leishmania donovani strains to sodium stibogluconate is drug specific and can be reversed by inhibiting glutathione biosynthesis. Antimicrobiol Agents Chemother. 2003;47:1529–35. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.5.1529-1535.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carter KC, Baillie AJ, Alexander J, Dolan TF. The therapeutic effect of sodium stibogluconate in the BALB/c mice infected with L. donovani is organ dependent. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1988;40:370–3. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1988.tb05271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carter KC, Hutchison S, Boitelle A, Murray HW, Sundar S, Mullen AB. Sodium stibogluconate resistance in Leishmania donovani correlates with greater tolerance to macrophage antileishmanial responses and trivalent antimony therapy. Parasitology. 2005;131:747–57. doi: 10.1017/S0031182005008486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor A, Murray HW. Intracellular antimicrobial activity in the absence of interferon-γ: effect of interleukin 12 in experimental visceral leishmaniasis in interferon- γ gene-disrupted mice. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1231–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.7.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray HW. Prevention of relapse after chemotherapy in a chronic intracellular infection: mechanisms in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. J Immunol. 2005;174:4916–23. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matthews DJ, Emson CL, McKenzie GJ, Jolin HE, Blackwell JM, McKenzie AN. IL-13 is a susceptibility factor for Leishmania major infection. J Immunol. 2000;164:1458–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.3.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dasgupta B, Roychoudhury K, Ganguly S, Kumar Sinha P, Vimal S, Das P, Roy S. Antileishmanial drugs cause up-regulation of interferon-gamma receptor 1, not only in the monocytes of visceral leishmaniasis cases but also in cultured THP1 cells. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2003;97:245–57. doi: 10.1179/000349803235001714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sudhandiran G, Shaha C. Antimonial induced increase in intracellular Ca2+ through non-selective cation channels in the host and the parasite is responsible for apoptosis of intracellular Leishmania donovani amastigotes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25120–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301975200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolday D, Berhe N, Britton S, Akuffo H. HIV-1 alters T helper cytokines, interleukin-12 and interleukin-18 responses to the protozoan parasite Leishmania donovani. AIDS. 2000;14:921–9. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200005260-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]