Abstract

Context: The Heart Disease Program (HDP) is a novel computerized diagnosis program incorporating a computer model of cardiovascular physiology. Physicians can enter standard clinical data and receive a differential diagnosis with explanations.

Objective: To evaluate the diagnostic performance of the HDP and its usability by physicians in a typical clinical setting.

Design: A prospective observational study of the HDP in use by physicians in departments of medicine and cardiology of a teaching hospital. Data came from 114 patients with a broad range of cardiac disorders, entered by six physicians.

Measurements: Sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value (PPV). Comprehensiveness: the proportion of final diagnoses suggested by the HDP or physicians for each case. Relevance: the proportion of HDP or physicians' diagnoses that are correct. Area under the receiver operating characterist (ROC) curve (AUC) for the HDP and the physicians. Performance was compared with a final diagnosis based on follow-up and further investigations.

Results: Compared with the final diagnoses, the HDP had a higher sensitivity (53.0% vs. 34.8%) and significantly higher comprehensiveness (57.2% vs. 39.5%, p < 0.0001) than the physicians. Physicians' PPV and relevance (56.2%, 56.0%) were higher than the HDP (25.4%, 28.1%). Combining the diagnoses of the physicians and the HDPs, sensitivity was 61.3% and comprehensiveness was 65.7%. These findings were significant in the two collection cohorts and for subanalysis of the most serious diagnoses. The AUCs were similar for the HDP and the physicians.

Conclusions: The heart disease program has the potential to improve the differential diagnoses of physicians in a typical clinical setting.

Over the last three decades, a large number of clinical decision support systems have been developed to advise physicians on patient diagnosis and management.1 There is increasing use of computer systems that provide alerts and reminders to physicians on tasks such as prescription of medication, ordering of investigations, and screening. Studies have found that these systems can improve the standard of care,2,3,4 quality of prescribing,5,6,7,8,9 and use of resources.10 However, with certain exceptions such as pathology,11 the diagnosis of chest pain,12 and electrocardiogram (EKG) analysis,13 most systems for assisting with diagnosis have yet to perform as well as or better than physicians alone.1 Typically, such diagnostic programs have been developed and tested using retrospective real or simulated clinical data. Performance often is good in the laboratory setting, but once deployed in a typical clinical setting the programs tend to be less successful.14,15

Before clinical deployment, a diagnosis program should ideally be tested in an intervention study in which patients, physicians, or clinics1,16,17 are randomized. However, an important prerequisite is to know the performance of the system in a genuine clinical setting, operated by the intended users (typically physicians), with clinical cases typical of those encountered in practice. Suitable standard diagnoses must be available with which to compare the program and the physicians (often termed the gold standard). Few studies have fulfilled all these criteria; most use prepared cases that may obscure some of the problems and inconsistencies of medical practice. In addition, most investigators avoid having physicians directly enter the data,14,18,19 despite the fact that the data entry process is often a major stumbling block in deployment of clinical information systems in the real world.20

The observational study described here evaluated a new type of cardiac differential diagnosis program. The program was deployed in a clinical setting, and real cases were entered by the physicians who were caring for those patients. Rather than trying to assess the diagnostic accuracy of the Heart Disease Program (HDP) in isolation, the program's diagnostic performance in matching the final diagnoses for each case was compared with the diagnostic accuracy of these physicians at matching the final diagnoses. This makes it easier to interpret whether a diagnostic performance measure represents improvement on the usual clinical ability of physicians, an approach advocated by Miller and Masarie21 and by Friedman and Wyatt.17 In effect, we measured whether the analysis of the data was more effective by the HDP than in the physicians' heads. Final diagnoses were assigned by follow-up and chart review. A Web-based medical record interface was developed to facilitate data collection and display of results.

Background: The Heart Disease Program

The Heart Disease Program (HDP) was designed to assist physicians in diagnosing heart disease, particularly conditions leading to hemodynamic dysfunction and heart failure. The program is based on a model of cardiac physiology and pathophysiology developed with the assistance of three cardiologists. The knowledge base is organized as a causal network of relations including causal probability and temporal and severity constraints. The diagnostic algorithm handles this as a generalization of a Bayesian Belief Network,22 allowing it to reason in terms of the possible mechanisms causing the observed findings, including their temporal relationships and the severity of causes necessary to account for the findings. These features, unique to the HDP, allow the program to model the cardiovascular system more naturally than previous approaches and simplify the addition of medical knowledge.

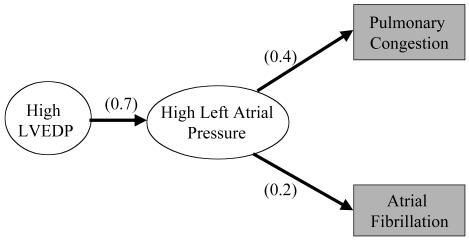

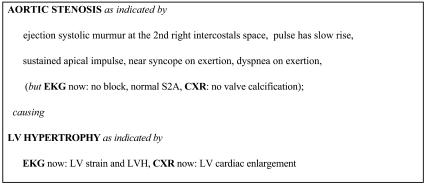

To perform a diagnosis, the HDP first uses its input data to specialize the network to the patient, including setting the prior probabilities of relevant diseases (such as baseline risk of coronary artery disease) based on the demographic features of the case (▶ ). The program accounts for the findings by searching for paths through the network from primary causes. It puts together a series of hypotheses, which are consistent sets of such paths from one or more causes that account for all of the findings. From the probabilities in the network, the program computes overall probabilities for the hypotheses and orders them. The program then presents summaries of the most probable hypotheses as the differential diagnosis. The diagnoses used for the evaluation described in this paper are the causes and significant syndromic nodes in the hypotheses of the differential diagnosis (a mean of 11 per case). These diagnoses include information on the temporal characteristic of diseases such as whether valvular disease is acute or chronic. They include a mixture of etiologic and pathophysiologic diagnoses. The HDP provides detailed explanations of complex cardiac cases, including the underlying physiology and the role of different clinical findings, by describing the paths in a hypothesis (▶ ). The explanations indicate which items of clinical evidence support each diagnosis, allowing physicians to assess the strength of evidence. Details of the diagnostic algorithms are described elsewhere.23,24 Over the last 15 years, the HDP has grown to cover a broad range of diagnoses in cardiology and includes diagnoses in several related areas of general medicine such as nephrology, hepatology, and pulmonology. The latter diagnoses are general categories rather than detailed analyses because they are intended to indicate the likelihood of noncardiac diagnoses requiring attention. The program is able to create differential diagnoses for any cardiac or cardiac-related problems and consider alternative causes of symptoms such as breathlessness, including asthma, lung cancer, and pneumonia. It is not currently designed to reason about conditions that do not share any signs and symptoms with diseases of the heart. It has undergone two previous evaluations in laboratory settings25,26 showing that performance was similar to that of cardiologists on cases collected and entered by a research fellow. However, significant differences of opinion among cardiologists assessing the diagnoses were noted, and the program had not been tested in a clinical setting.

Figure 1.

A part of the Heart Disease Program. Findings are in shaded boxes; numbers are probabilities. LVEDP = left ventricular end diastolic pressure.

Figure 2.

An example of the Heart Disease Program's diagnostic output with explanations showing how each diagnosis is justified by clinical data. EKG = electrocardiogram; CXR = chest x-ray; LV = left ventricle; LVH = left ventricular hypertrophy.

To allow physicians to access the system on the hospital wards, Web-based input forms were developed. These allow case entry, diagnosis review, revision of cases to add or remove input data, and critique of the program over the Web.27,28 Clinical data can be entered in a layout similar to a standard clinical write-up including symptoms, past medical history, vital signs, physical examination, and relevant investigations. Once the initial Web form is submitted, follow-up questions are returned to the physician asking, for example, about the timing and severity of symptoms or clinical examination findings. There may be up to two further short forms requesting more clarification before the case is complete. The additional forms are intended to simplify the Web pages and reduce extraneous detail. They are not part of the diagnostic process.

Methods: The Clinical Trial Design

Stead et al.29 have proposed a five-stage framework for the evaluation of medical informatics projects:

Problem definition.

Bench testing in the laboratory.

Early field trials under the direct control of the original investigator. This is to determine whether the system performs as designed in a realistic environment.

Field testing in new or unfamiliar settings.

Definitive study of the system's efficacy during routine operational use.

Results here are from a prospective observational study (stage 3) designed to test in a field setting the diagnostic accuracy, ease of use by physicians, and the potential effect of the output of HDP on physicians' decisions. The null hypothesis was that “the Heart Disease Program's differential diagnoses are no different from those of the unassisted physicians.” This could be rejected if the HDP was significantly better or worse than the physicians on the metrics chosen. The trial was planned in two cohorts to allow any problems or deficiencies discovered in the first part to be corrected and the program tested with a second statistically valid sample. During the collection of each cohort, the knowledge base and inference mechanisms of the program were held stable as suggested by Miller et al.,30 Wyatt and Spiegelhalter,16 and others. However, the physicians in the second cohort were educated to record a fuller list of differential diagnoses, which may have affected their performance as discussed below.

To test the use of the HDP in a clinical setting, physicians entered their own patients' clinical data via the Web interface. This approach gave straightforward access to the HDP from most of the computers used by physicians at the New England Medical Center, without requiring any special preparation for each computer. It also permitted monitoring of cases as they were entered. No personally identifiable data were transmitted over the Web.

The physicians who took part in this study were recruited from the medical staff at the New England Medical Center. Five were senior residents on the general medical or cardiology services, and one was an attending physician in primary care. These physicians received sufficient training to enter cases independently, and user support was available if they had any problems using the system (although they were required to enter all cases independently). This training took about 45 minutes. The physicians were requested to select patients for whom they were currently caring and for whom they might consult a diagnostic program. Patients had to have at least one of the following: breathlessness, peripheral edema or ascites, abnormal heart sounds or murmurs, or heart failure. Other cardiac problems such as myocardial infarction, which may be complicated by heart failure, were included. Case selection and entry were carried out by the participating physicians and were done entirely independently of the researchers. The intention was to expose the HDP to all the types of cases it might need to analyze rather than focus on only particularly complex or challenging cases as in some other studies.30,31

No patients were excluded from the study once entered due to being inappropriate, but in the few patients who had cardiac and noncardiac diseases (such as a tumor), only the cardiac diagnoses were analyzed. Appendix C shows diagnoses that were weighted 0 (available as an online data supplement at <www.jamia.org>). After each case was entered into the Web forms of the HDP, the physician completed another form detailing his or her diagnoses. Once that form was submitted, the analysis of the program was returned (so that the physicians did not see the diagnoses until they had submitted their own differential diagnosis). Finally, each participating physician completed a critique form in which he or she rated the usefulness of the program in the particular case.

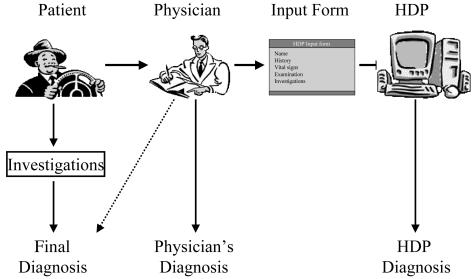

To assess the diagnostic accuracy of a program, it is necessary to compare all the diagnoses for each patient with expert opinion or some other standard. Due to the significant differences of opinion between experts noted in previous studies, final diagnoses based on follow-up were used here. The clinical information contributing to the diagnoses in each part of the study is shown in ▶ and the case data in Appendix B (available as an online data supplement at <www.jamia.org>). In addition to the physician's diagnosis (column 2) and the HDP diagnosis (column 3), each case was assigned a final diagnosis (column 1) from detailed review of the relevant discharge summary or patient chart performed by one researcher (HSFF) at least two weeks after the patient was entered into the HDP. Further investigation and follow-up were carried out by the patient's usual clinical team, and these data were used for the study. Most of these patients were investigated extensively by the cardiology service so that objective data were available from cardiac investigations. At least one cardiac catheterization, echocardiogram, ventriculogram, or thallium scan was performed in 46 of the 49 cases in the first cohort and 53 of 64 cases in the second cohort. (More details can be found in Appendix A, available as an online data supplement at <www.jamia.org>.) Cardiac ejection fraction was measured in 70% of the second cohort. Standard diagnostic criteria were used where applicable (such as World Health Organization [WHO] criteria for myocardial infarction). Final diagnoses were defined prior to the analysis of the differential diagnoses of the HDP and the physicians.

Figure 3.

Trial design illustrating the flow of clinical information. Note that the final diagnosis was based on the most clinical data, and the Heart Disease Program (HDP) received data only via the physicians.

Analysis Methods

All three sets of diagnoses were entered into a database using the same diagnostic codes as the HDP. There are 228 codes for 180 types of diagnoses and physiologic states, of which 62 categories were present in the study and used in the analysis (Appendix A). Because there may be multiple terms used for similar physiologic states of the cardiovascular system, a look-up table was created to match equivalent terms (Appendix C). For example, related general medical diagnoses such as “hypothyroidism,” “treated hypothyroidism,” and “myxedema” were grouped for analysis. The table included a severity score from 1 to 5 based on the clinical importance of each diagnosis, rated by consensus of two cardiologists prior to analysis (for example, aortic-sclerosis = 2, myocardial infarction = 5, see Appendices A and C). The score allowed subanalysis of diagnostic performance on the most serious diagnoses. It also allowed items in the diagnosis such as atrial stretch or other clinically less relevant physiologic states to be excluded from the analysis.

Sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value (PPV) apply to specific diagnoses such as myocardial infarction. They were calculated for each of the diagnoses that appeared in the cases. Overall performance was calculated as a mean value for all diagnoses and weighted for the number of occurrences of each (to adjust for the many infrequent diagnoses).32 Comprehensiveness and relevance (metrics similar to sensitivity and PPV and proposed by Berner et al.18), were calculated for each case. Comprehensiveness is the proportion of “correct” diagnoses suggested by the HDP or physicians. For example, if the comparison is between the HDP and the final diagnosis for a particular case, where the final diagnosis contains six diagnoses, three of which are present in the diagnosis of the HDP, then the comprehensiveness of the HDP is 3/6, i.e., 50%. Relevance is the proportion of HDP or physicians' diagnoses that are correct. For example, in the above comparison, if the HDP has ten diagnoses, three of which are present in the final diagnosis, then the relevance of the HDP is 3/10, i.e., 30%. These metrics give a good measure of overall performance, particularly in situations in which each type of diagnosis may be present in only a small number of cases or even just one18 (see Appendix A). In addition, comprehensiveness and relevance scores are calculated for each individual case; therefore, differences in scores can be compared using standard statistical tests. In comparing comprehensiveness and relevance scores for the HDP and the physicians, the null hypothesis is that the two scores for each case are the same. We, therefore, test whether the scores from one set of differential diagnoses (such as the HDP) are significantly different from the mean of the other scores (such as the physicians). We used the nonparametric Wilcoxon signed rank test because the data are not normally distributed. The JMP statistical package (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used for the statistical tests. The calculation of these metrics has been described in detail in an earlier measurement study,32 which showed that comprehensiveness has a similar value to mean sensitivity and relevance a similar value to mean PPV for studies with multiple diagnoses per case.

To indicate the potential effect of the physician's use of the HDP, the diagnoses from the physician and the HDP were combined into one list (union of both lists). The diagnoses of the HDP, the physicians, and the combination were compared with the final diagnoses. To assess whether the scores of the HDP and the physicians were based on different types or severities of diagnosis, the above analyses were repeated including only the most serious diagnoses (scores 4 and 5, Appendices C and D, on line at <www.jamia.org>).

Creating ROC Curves from the HDP Output

Assessing the performance of a diagnostic tool using sensitivity and specificity has an important limitation. The sensitivity and specificity reported depend on the threshold used to determine correct and incorrect responses. One solution to this problem is to create a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve.33 This requires the generation pairs of sensitivity and specificity values at different thresholds. The HDP labels each diagnosis with a pseudoprobability score normalized to the 0–1 range. All possible diagnoses for each case were filtered according to that score to generate several files of diagnoses at thresholds between 0 and 1 (this is equivalent to setting different thresholds for a numeric blood test result to determine whether a disease is present). The sensitivities and specificities compared with the final diagnosis were calculated for each disease present. Finally, mean sensitivity and mean specificity were calculated for each file. The resulting pairs of sensitivity and 1− specificity were plotted to create the ROC curve, and the area under the curve (AUC) was then calculated. This method has been described in detail.32 ROC curves can be created also for individual diagnoses if they are present frequently (not shown here).

In addition, the performances of physicians from the first and second cohorts were assessed by ROC curves. This was feasible because the second group of physicians were asked to give more complete diagnosis lists, which will tend to raise their sensitivity at the expense of specificity, thus representing a different point on the ROC curve.

Data Collection

Clinical data on 127 patients were entered in two cohorts of 60 and 67. Full follow-up information is available on 114 subjects with a mean age of 66 years (range, 29 to 91) and 40% women. Forty-nine of the first cohort had follow-up; the other 11 were not traceable due to difficulties in matching cases to hospital ID number (because identification data could not be sent over the Web). Using the secure hospitale-mail system, 65 of 67 cases had follow-up in the second cohort. Six physicians, mostly senior medical residents, entered cases (four in the first cohort, three in the second, one contributed to both). A broad range of cardiac diseases was included in the cases. Items in the final diagnosis are listed in Appendix A and were based heavily on investigations.

Results

▶ shows the results of comparing the HDP and the physicians with the final diagnosis. The HDP had substantially higher sensitivity than the physician alone (53.0% vs. 34.8%), and its comprehensiveness was significantly higher than the physician (57.2% vs. 39.5%, p < 0.0001). Combining the HDP and physicians' diagnoses further improved performance relative to the physician alone. These comparisons also were significant in both cohorts individually (p < 0.05 or better, ▶ ). Values for specificity, PPV and relevance were higher for the physicians associated with a lower number of diagnoses recorded by them (mean number of diagnoses for physicians, 2.0 first cohort, 4.1 second cohort; HDP, 10.7 and 11.2, respectively). In seven cases the physicians did not include any diagnoses on their differential list (see Appendix B). Reanalysis without these seven cases did not affect the statistical significance of the results (comprehensiveness of the physicians rose from 39.5% to 42.1%). Because these cases included a number of serious final diagnoses, they were kept in the study.

Table 1.

Performance (%) Compared with the Final Diagnosis.

| Sensitivity | Comprehensiveness | Specificity | PPV | Relevance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HDP&physician | 61.3 | 65.7 | 77.0 | 29.1 | 32.0 |

| HDP | 53.0 | 57.3* | 75.6 | 25.4 | 28.1 |

| Physician | 34.8 | 39.5* | 93.9 | 56.2 | 56.0 |

PPV = positive predictive value; HDP = Heart Disease Program.

p < 0.0001

p < 0.0001

p < 0.043

p < 0.0001.

Positive predictive value (PPV), relevance, and specificity are depressed by many examples with no data in final diagnosis.

p = 0.039.

Table 2.

Performance Breakdown on the Two Separate Cohorts in the Study (%)

| HDP&Physician | HDP Alone | Physician | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehensiveness of comparison with the final diagnosis | |||

| First cohort | 58.5 | 52.9* | 19.4* |

| Second cohort | 70.1 | 60.4** | 53.7** |

| All 114 cases | 65.7 | 57.3*** | 39.0*** |

| Relevance for comparison with the final diagnosis | |||

| First cohort | 33.6 | 32.0 | 49.5 |

| Second cohort | 28.1 | 25.0 | 59.6 |

| All 114 cases | 32.0 | 30.0 | 56.0 |

▶ shows the effect of a subanalysis to test whether the HDP performed well on the most important diagnoses (grades 4 and 5 using the weighting system described above and in Appendices A and C). This was intended to address the possibility that the higher comprehensiveness of the HDP was due to the inclusion of minor items in its diagnoses that were not thought significant by the physicians. The physicians maintained their performance, but the sensitivity and comprehensiveness of the HDP fell somewhat. The HDP was still significantly more comprehensive than the physicians alone (43.8% vs. 37.2%, p < 0.039), indicating that the physicians were missing some serious and potentially life-threatening conditions.

Table 3.

Performance (%) of the Program and Physicians on Serious Diagnoses*

| Sensitivity | Comprehensiveness | Specificity | PPV | Relevance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HDP&physician | 59.5 | 52.5 | 76.6 | 22.7 | 23.6 |

| HDP | 48.9 | 43.8† | 75.6 | 19.9 | 22.5 |

| Physician | 36.8 | 37.2† | 93.1 | 45.0 | 42.2 |

HDP = Heart Disease Program.

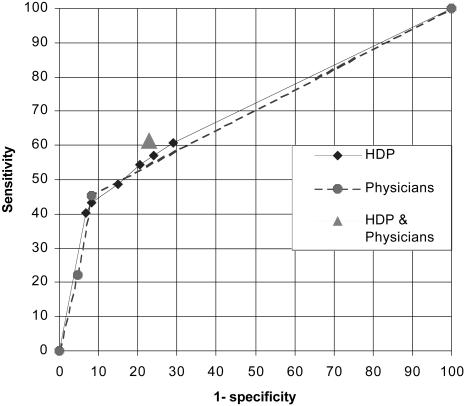

▶ shows the ROC curve of the HDP compared with the final diagnoses. The AUC for the HDP is 70.1%. To assist in comparing the physicians' lower sensitivity and higher specificity, with the range of possible sensitivities and specificities of the HDP, the physicians' values for the first and second cohorts also are shown as an ROC curve. It is clear that their discrimination is very similar to the HDP (area under the curve was 68.4% physicians vs. 70.1% HDP), but their best sensitivity is lower than the usual output of the HDP (45.4% physicians vs. 54.5% HDP). Also plotted is the performance of the combination of the HDP and physicians, which gives slightly better discrimination than the program or physicians alone.

Figure 4.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of the performance of the Heart Disease Program (HDP) compared with the final diagnoses. Also shown is the physicians' performance for first and second cohorts. The combination of the HDP with the physicians is shown as one point.

Usability

A median of 95 clinical data items were entered per case (range, 59 to 151). Times of case entry and case analysis were recorded automatically. Median case entry time was 15.0 minutes, with 90% of cases entered in less than 26 minutes. The proportion of data in each part of the case also was measured. Assuming constant time per data item, physicians were estimated to spend a median of 5.04 minutes on history, 0.94 on vital signs, 2.52 on physical examination, and 6.14 on investigations. ▶ shows results from the physician's critique form filled in after each case. The seven “no help” cases in the first cohort include five in which the program did not initially run due to technical problems. Sixty-eight percent of cases in the second cohort had positive comments.

Table 4.

Physicians' Answers to Questions on the Critique Form Completed after the Heart Disease Program's (HDP's) Diagnosis Was Returned

| Response from the Physician about Each HDP Analysis | First Cohort | Second Cohort |

|---|---|---|

| Solves a difficult diagnostic question | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Helpfully guides further investigations | 11 (29%) | 6 (13%) |

| Confirms your opinion | 8 (21%) | 18 (40%) |

| Organizes the data usefully | 1 (3%) | 7 (16%) |

| Suggests additional possibilities/useful ideas | 11 (29%) | 12 (27%) |

| Not helpful | 7 (18%) | 1 (2%) |

| Total responses/cases analyzed | 38/49 | 45/65 |

Discussion

These results show that the HDP had a sensitivity and comprehensiveness significantly greater than the physicians entering the cases when compared with the final diagnoses. Combining the diagnoses of the HDP and the physicians further improved sensitivity without significantly reducing specificity and should help to indicate the program's potential impact. Miller34 suggests that the important question is “whether the clinician plus system is better than the unaided user with respect to the specified task or problem.” However, intervention studies are required to confirm the true effect of the HDP in practice.

It is important to note that more data were available at the time of final diagnosis (from chart review) than when the case was entered, likely causing an underestimate of the performance of the HDP and the physicians in this study. Despite this, the final diagnosis should provide the best measure of the patient's true pathophysiologic state and correct for some of the variability seen when expert opinion is used as a standard for comparison. An earlier study looked at the performance of the HDP compared with the expert opinion of cardiologists.35 In that study, the cardiologists were asked to generate a differential diagnosis list based on reading the case summaries from the HDP (but blinded to both the diagnoses of the HDP and the final diagnoses). The results were very comparable with those in the current study, with the HDP showing significantly higher comprehensiveness than the physicians (58% vs. 34%, p < 0.001). This indicates that the physicians were missing many items that a cardiologist thought should have been in their differential diagnosis, even though the physicians had seen the patient and compiled the case description the cardiologists used.

The sensitivity and comprehensiveness of all diagnoses improved in the second cohort (▶). This was probably due in part to better data entry, with more clinical data entered in the second cohort, and also a fall in the mean number of final diagnoses from 5.5 to 4.5 (reason unknown). The physicians showed the largest increase in comprehensiveness associated with a rise in the mean number of diagnoses entered from 2.0 to 4.1 between cohorts. This was probably due in part to requests to participating physicians to provide a broader differential diagnosis. ▶ shows this rise in sensitivity on the ROC curve and a suggestion that the discrimination of the physicians was also higher in the second cohort. It is not clear whether this represents more typical behavior for physicians or an improvement in clinical practice induced by the study. Sensitivity and comprehensiveness were emphasized in this evaluation more than PPV and relevance because the HDP was used to provide an initial differential diagnosis. In this situation, missing a diagnosis is more important than suggesting an incorrect diagnosis because the patient will normally go on to further investigation.

This study may be compared with an evaluation of the medical diagnosis programs, QMR, Dxplain, Iliad, and Meditel, by Berner et al.18 In that study, comprehensiveness ranged from 25% to 38%, and relevance ranged from 19% to 37%. The relevance of the HDP is in the same range, but the comprehensiveness is substantially higher. The lower comprehensiveness scores in Berner's study are likely due in part to the wider range of medical diagnoses covered by those programs. However, the HDP was tested with direct entry of data by physicians and more direct standards for comparison. A study by Elstein et al.14 looked at direct clinical data entry by physicians from patients with a variety of general medical problems. They found that Iliad had a sensitivity of 38% for the final diagnosis (based on follow-up and investigations as with this study), which is midway between the 43% for attending physicians and 33% for residents. Friedman et al.36 extended this work to assess the effect of two diagnostic systems, Iliad and QMR, on the diagnostic accuracy of physicians and medical students. They developed new metrics to assess the quality of diagnoses based on the presence and ranking of a diagnosis on a program's list. Their results showed that “correct diagnoses appeared in subjects' hypothesis lists for 39.5% of cases prior to consultation and 45.4% of cases after consultation…” with the program.37 However, this study was also performed in a nonclinical setting with precompiled cases. Moens19 evaluated the diagnosis program AI/Rheum with 1,570 patients seen consecutively in a rheumatology outpatient clinic. Sensitivity (weighted mean for all diagnoses) was 84% for definite diagnoses and 43% for probable diagnoses, compared with 53% here. Specificity was high at 98%. Moens' data came from forms filled in by specialist rheumatologists, rather than residents such as those participating in the current study. As the ROC curve in ▶ indicates, the HDP and the physicians had similar discriminations but markedly different balances between sensitivity and specificity. The lower specificity and PPV of the HDP should be offset in part by the detailed explanations given for each diagnosis (▶), allowing the user to assess the credibility of the clinical data supporting each item.38,39,40 This dialogue between the physician and program is a key assumption in ethical approval of clinical decision support systems.41

It should be noted that all the studies described here differed to a greater or lesser extent in the way data were collected and final diagnoses were defined, making precise comparison of results difficult. Better standardization of such studies would be helpful to improve our understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of the various programs. This could include sharing of test cases and evaluation metrics. There also are potential problems in analyzing differential diagnoses where multiple related diagnoses may be present in one patient. The function of the HDP is to help diagnose typical cardiology problems as seen in the acute medical unit or outpatient clinic, not just provide a major diagnosis label. Therefore, a combination of disease states and physiologic abnormalities often is the correct response for a case. Also, the patient often will have some known cardiac problems but present in an unstable state with one or more important changes or areas of decompensation. This makes it difficult to focus purely on major diagnostic categories and also means that multiple related diagnoses may be present in one patient, such as myocardial infarction and heart failure. Many of the diagnoses also overlap in that they have similar causes but differ in manifestations or severity or time course. To deal with this issue, we combined a number of the diagnoses that are very similar (such as hypertension and history of hypertension) in which the distinctions made by the program were unlikely to be made by the physicians. We were conservative in doing this and left many that overlap in one way or another. The consequence is that the relevance and PPV measures for the HDP suffer. That is, there are many diagnoses given by the program that are not included in either the physician's diagnosis or the final diagnosis, because the physicians probably did not think to make the distinction or that it was adequately covered by the diagnostic statements that were made. We also experimented with a score of 0.5 for partial matches between similar disease states such as septic shock and cardiogenic shock or aortic sclerosis and aortic stenosis. This increased the score of the HDP for comprehensiveness by approximately 2% from the figures shown in ▶.

Giving physicians flexibility to enter cases in their own fashion is a powerful test of programs such as this and can lead to cases' being entered with insufficient or inaccurate data. Alternatively, the physicians may enter too many previously known diagnoses and, therefore, leave the clinical situation so well specified that meaningful measurement of diagnostic accuracy is not possible. Variations in the amount and nature of data entered on a particular patient may lead to problems with conflicting data. These differences seem to be due in part to the setting in which the patient is being seen and the severity of the suspected disease. Outpatients from the general medicine clinic tended to present differently from hospital inpatients and often had fewer investigations. In addition, the well-recognized variations in how doctors obtain and record clinical data caused many interesting problems. Physical examination was a particularly difficult issue because the program puts considerable weight on these data. The reporting of cardiac murmurs varied from the oversimple “systolic murmur” without qualification to detailed and accurate descriptions of character, location, radiation, presence of thrill, and effect of maneuvers such as deep inspiration. A more interactive interface such as that used by the Quick Medical Reference (QMR) could ensure higher quality data, but QMR may require one to four hours for entry of one case.31,42

There are a number of limitations to this study. First, most cases were entered by a group of five senior medical residents. To improve generalizability, it will be important to recruit a broader range of physicians, preferably at more than one site. Second case selection was performed by the physicians themselves. This made the study very challenging for the HDP with a wide range of diagnoses and patient types. Other studies have emphasized difficult cases that typically require a diagnostic consult,31 but we feel the case selection used here suits the HDP's role of explaining what combinations of cardiovascular diseases and physiologic states account for the findings. Despite this, consecutive sampling techniques and the selection of some additional challenging cases may improve external validity.16

The use of the Web was crucial to performing this study but also had disadvantages. The original forms were quite limited in the organization of text and data entry boxes; it also was difficult to allow interactive questions. These limitations of the Web have largely been circumvented by recent technological developments. Early in the evaluation the program failed to return a diagnosis on six cases, generally because conflicting data had been entered. These cases were rerun after correction. The program was modified after the first cohort, which prevented most of these problems.

Probably the most important barrier to deploying a diagnostic program is having physicians enter “structured” data. Discussions with participating physicians indicate that these difficulties stem, in part, from lack of familiarity with the system, but particularly the time required to enter a case (median of 15 minutes). For routine clinical use, programs such as the HDP must be a positive boost to the quality and productivity of physician's practice. It will be essential to integrate the program into a clinical network to download directly all available data on demographics, investigations, and possibly vital signs. The physician then could be presented with a basic summary of existing data and asked to add details of history and physical examination. Using the timings calculated from this study, such an automated system could potentially reduce case entry time to 5 or 6 minutes and perhaps save time by organizing the data. We also are experimenting with data collection directly from patients.

Conclusions

The performance of the HDP was encouraging on both cohorts and on considering only serious diagnoses. Further work will concentrate on improving the specificity and knowledge base of the HDP. The approach of having physicians enter cases directly over the Web in the course of their clinical work was shown to be an effective way of testing the effectiveness and usability of the system. Future assessments of diagnosis programs should include real data entered, or at least collected, by the physicians who will use the system and not rely purely on precompiled “teaching cases.” In addition, investigators should use standard metrics such as sensitivity, specificity, and ROC curve analysis or well-validated new metrics to allow studies to be compared and reproduced.

A definitive study of the performance of the HDP will require a randomized intervention trial measuring changes in physician diagnoses and management decisions and, ultimately, patient outcomes. Given the safety and cost implications of such studies, it is clearly important that the performance of a decision support program is well characterized in typical clinical settings first, as described here.

The HDP can be accessed over the Web and cases run at: <http://www.medg.lcs.mit.edu/projects/hdp/hdp-world.html>.

Supplementary Material

Parts of this material have been presented at the AMIA Fall symposiums in 199743, 199835, 199944, and 200032.

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant R01-HL33041. The study was approved by the New England Medical Center Human Investigation Review Board. The authors thank the cardiology and General Medical Associates (GMA) departments at New England Medical Center for permission to use patient data; members of the medical resident and GMA staff for case entry; and John Wong, Peter Szolovits, James Stahl, and Laura Smeaton for their advice.

References

- 1.Hunt DL, Haynes RB, Hanna SE, Smith K. Effects of computer-based clinical decision support systems on physician performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA. 1998;280:1339–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDonald CJ, Hui SL, Smith DM, et al. Reminders to physicians from an introspective computer medical record. A two-year randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 1984;100:130–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Safran C, Rind DM, Davis RB, et al. Guidelines for management of HIV infection with computer-based patient's record. Lancet. 1995;346:341–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Overhage JM, Tierney WM, Zhou XH, McDonald CJ. A randomized trial of “corollary orders” to prevent errors of omission. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1997;4:364–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walton RT, Gierl C, Yudkin P, Mistry H, Vessey MP, Fox J. Evaluation of computer support for prescribing (CAPSULE) using simulated cases. BMJ. 1997;315:791–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rind DM, Safran C, Phillips RS, et al. Effect of computer-based alerts on the treatment and outcomes of hospitalized patients. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1511–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen SN, Armstrong MF, Briggs RL, Feinberg LS, Mannigan JF, et al. A computer-based system for the study and control of drug interactions in hospitalized patients. In: Morselli PL, Feinberg LS, Mannigan JF, et al. (eds). Drug Interactions. New York: Raven Press, 1974, pp 363–74.

- 8.Evans RS, Pestotnik SL, Classen DC, et al. A computer-assisted management program for antibiotics and other antiinfective agents. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:232–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bates DW, Leape LL, Cullen DJ, et al. Effect of computerized physician order entry and a team intervention on prevention of serious medication errors. JAMA. 1998;280:1311–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tierney WM, Miller ME, Overhage JM, McDonald CJ. Physician inpatient order writing on microcomputer workstations. Effects on resource utilization. JAMA. 1993;269:379–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heckerman DE, Nathwani BN. An evaluation of the diagnostic accuracy of Pathfinder. Comput Biomed Res. 1992;25(1):56–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Selker HP, Beshansky JR, Griffith JL, et al. Use of the acute cardiac ischemia time-insensitive predictive instrument (ACI-TIPI) to assist with triage of patients with chest pain or other symptoms suggestive of acute cardiac ischemia. A multicenter, controlled clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:845–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willems JL, Abreu-Lima C, Arnaud P, et al. The diagnostic performance of computer programs for the interpretation of electrocardiograms. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1767–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elstein AS, Friedman CP, Wolf FM, et al. Effects of a decision support system on the diagnostic accuracy of users: a preliminary report. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1996;3:422–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wyatt J. Lessons learned from the field trial of ACORN, an expert system to advice on chest pain. Medinfo. 1989;6:864–8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wyatt J, Spiegelhalter D. Evaluating medical expert systems: what to test and how?. Med Inform (Lond). 1990;15:205–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedman C, Wyatt J. Evaluation Methods in Medical Informatics. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1996.

- 18.Berner ES, Webster GD, Shugerman AA, et al. Performance of four computer-based diagnostic systems. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1792–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moens HJB. Validation of AI/Rheum knowledge base with data from consecutive rheumatological outpatients. Methods Inf Med. 1992;31:175–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohane I. Getting the data in: three year experience with a pediatric electronic medical record system. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1994; 457–461. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Miller RA, Masarie FE, Jr The demise of the “Greek Oracle” model for medical diagnostic systems. Methods Inf Med. 1990;29:1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montironi R, Whimster WF, Collan Y, Hamilton PW, Thompson D, Bartels PH. How to develop and use a Bayesian Belief Network. J Clin Pathol. 1996;49:194–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Long WJ, Fraser H, Naimi S. Reasoning requirements for diagnosis of heart disease. Artif Intell Med. 1997;10(1):5–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Long W. Medical diagnosis using a probabilistic causal network. Appl Artif Intell. 1989;3:367–83. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Long WJ, Naimi S, Criscitiello MG. Development of a knowledge base for diagnostic reasoning in cardiology. Comput Biomed Res. 1992;25:292–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Long WJ, Naimi S, Criscitiello MG. Evaluation of a new method for cardiovascular reasoning. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1994;1:127–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Long WJ, Fraser H, Naimi S. Web interface for the Heart Disease Program. Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp. 1996;762–766. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Fraser HS, Kohane IS, Long WJ. Using the technology of the World Wide Web to manage clinical information. BMJ. 1997;314:1600–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stead WW, Haynes RB, Fuller S, et al. Designing medical informatics research and library—resource projects to increase what is learned. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1994;1:28–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller RA, Pople HE Jr, Myers JD. Internist-1, an experimental computer-based diagnostic consultant for general internal medicine. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:468–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bankowitz RA, McNeil MA, Challinor SM, Parker RC, Kapoor WN, Miller RA. A computer-assisted medical diagnostic consultation service. Implementation and prospective evaluation of a prototype. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:824–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fraser H, Long W, Naimi S. New approaches to measuring the performance of programs that generate differential diagnoses using ROC curves and other metrics. Proc AMIA Fall Symp. 2000;255–259. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143(1):29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller RA. Evaluating evaluations of medical diagnostic systems. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1996;3:429–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fraser H, Long W, Naimi S. Differential diagnoses of the Heart Disease Program have better sensitivity than resident physicians. Proc AMIA Fall Symp. 1998;622–626. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Friedman C, Elstein A, Wolf F, et al. Measuring the quality of diagnostic hypothesis sets for studies of decision support. Medinfo. 1998;9(pt 2):864–868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Friedman CP, Elstein AS, Wolf FM, et al. Enhancement of clinicians' diagnostic reasoning by computer-based consultation: a multisite study of 2 systems. JAMA. 1999;282:1851–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szolovits P, Patil RS, Schwartz WB. Artificial intelligence in medical diagnosis. Ann Intern Med. 1988;108:80–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suermondt HJ, Cooper GF. An evaluation of explanations of probabilistic inference. Comput Biomed Res. 1993;26:242–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li YC, Haug PJ, Lincoln MJ, Turner CW, Pryor TA, Warner HH. Assessing the behavioral impact of a diagnostic decision support system. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1995;805–809. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Forsythe DE, Buchanan BG. Broadening our approach to evaluating medical information systems. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1991;8–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Wolfram DA. An appraisal of INTERNIST-I. Artif Intell Med. 1995;7(2):93–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fraser H, Long W, Naimi S. Comparing complex diagnoses: a formative evaluation of the Heart Disease Program. Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp. 1997:853.

- 44.Fraser H, Long W, Naimi S. CompareDx: a software toolkit for measuring the performance of programs that generate multiple diagnoses. Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp. 1999:1060

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.