SYNOPSIS

Objective

This study was conducted to determine the effect of state Universal Newborn Hearing Screening legislation on the percentage of infants having their hearing screened within one month of birth.

Methods

Hearing screening data for 2000–2003 were obtained from state hearing screening programs. States with Universal Newborn Hearing Screening legislation were categorized according to legislation type and implementation status, and hearing screening rates were compared between states with implemented legislation and states with no legislation.

Results

Hearing screening rates among states that implemented Universal Newborn Hearing Screening legislation were significantly higher than rates in no-legislation states throughout the study period, although the mean screening rate among no-legislation states increased substantially from 2000 through 2003. The percentage of states attaining a 95% national screening quality indicator in each year was substantially greater among states with implemented legislation. In 2003, 76% of states with implemented Universal Newborn Hearing Screening legislation reported screening at least 95% of infants, compared with 26% of states without legislation. Although there is a greater likelihood of meeting the national screening target with Universal Newborn Hearing Screening legislation than without, other factors such as collaborative relationships and federal funding can also influence this outcome.

Conclusion

State legislation has had a positive effect on hearing screening rates and is one tool states can use to help ensure that infants are screened for hearing loss.

During the 20th century, state and federal legislation proved to be an important component in many public health achievements, including immunization mandates, standards ensuring safe drinking water, and requirements to wear seat belts.1 From the early 1960s to the mid-1980s, all states passed legislation that required newborn infants to be screened for phenylketonuria (PKU), subject in varying degrees to parental consent.2 Subsequently, states have added other disorders to newborn screening programs, generally by state legislation or by rules and regulations.3 In the 21st century, legislation continues to play an important role in public health.

Newborn hearing screening initially became a focus of state legislation beginning in the 1970s, with legislation targeted at high risk populations (e.g. children in the neonatal intensive care unit). More recently, state legislation requiring the screening of most babies through audiologic-based testing, also known has universal newborn hearing screening (UNHS), has been enacted. The concept of UNHS was formally endorsed by the National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement in 1993 and by the Joint Committee on Infant Hearing (JCIH) in a 1994 Position Statement.4,5 Hawaii and Rhode Island were the first states to pass UNHS legislation in the early 1990s. By 2005, a total of 37 states had passed UNHS legislation either requiring or strongly encouraging hearing screening of newborn infants. In addition, even those states without legislation have programs in place to coordinate and promote UNHS and related services.

Congenital hearing loss (HL) is a common birth defect that affects one to three infants per 1,000 live births, or from 4,000 to 12,000 children annually.6,7 Studies have shown that children with a delayed diagnosis of HL can experience preventable delays in speech, language, and cognitive development.8–10 In response, states have implemented what are commonly referred to as Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) programs to help ensure that infants with HL are identified and receive intervention services as early as possible.

Hearing screening is not mandated by federal law, although the Children's Health Act of 200011 authorized federal programs to support UNHS activities at the state level. Since then, funds have been distributed to states and territories via grants and cooperative agreements from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). States use this federal money to enhance EHDI programs and develop corresponding tracking systems. Tracking systems help states monitor their programs and ensure that infants and children receive recommended screening and follow-up services.

For screening to be considered universal, it should be offered to all or almost all infants. The Joint Commission on Infant Hearing (JCIH), which was established to make recommendations concerning newborn hearing screening and the early identification of children with or at risk for hearing loss, adopted position statements endorsing UNHS in 1994 and 2000.5,12 The 2000 JCIH statement set benchmarks and quality indicators for evaluating success in the implementation of UNHS programs. The first benchmark was that a minimum of 95% of all infants should be screened either during their birth admission or before 1 month of age. Following the JCIH position, we define those UNHS programs in which at least 95% of infants are estimated to have received hearing screening before 1 month of age as meeting the UNHS quality indicator.

While the states of Colorado and Wisconsin have documented the impact of UNHS legislation on newborn hearing screening rates within their states, 13,14 the effects of legislation at the national level are largely unknown. The hypothesis of this study is that UNHS legislation has a positive effect on the number of infants screened before 1 month of age. Our primary objective was to determine if states with legislation screened a higher percentage of infants for HL than did states without UNHS legislation. In addition, we examined the impact of implementing legislation on the likelihood that a state attains the national benchmark or quality indicator of an infant hearing screening rate of 95% or greater. Finally, we were interested in ascertaining factors other than legislation that may have contributed to an increase in screening rates for states without UNHS legislation.

METHODS

Estimated state hearing screening data for calendar years 2000 through 2003 were obtained from the Directors of Speech and Hearing Programs in State Health and Welfare Agencies' (DSHPSHWA) annual survey of state EHDI programs.15 (See Appendix Table 1, available from: URL: http://www.publichealthreports.org.) This data is estimated because reports from hospitals to the state about the number screened for HL may not be exact and the EHDI tracking systems in several states are not fully developed. Among other data items requested by DSHPSHWA, states were asked to voluntarily report data used to determine the percent of infants screened for HL, referred for and receiving follow-up testing, identified with HL, and enrolled in intervention services.

States with UNHS legislation that had been implemented or passed in the study years were identified by examining organizational websites (American Speech and Hearing Association and National Center for Hearing Assessment and Management), state CDC-EHDI cooperative agreement applications, annual state reports, and state websites. Copies of the legislation and any related administrative rules were obtained through the Internet or by contact with state EHDI program personnel. Territories of the U.S. were not included in this study.

We abstracted information from legislation and administrative rules (Appendix Table 2, available from: URL: http://www.publichealthreports.org.) including the date legislation was enacted, the date the law was to be implemented, and the population that was required to be screened. Using this information, states were classified into one of three categories for each year from 2000 through 2003 (see Appendix Table 1, available from: URL: http://www.publichealthreports.org). The first category, implemented legislation, included those in which legislation had been passed and implemented requiring the screening of all newborns; however, actual observed screening rates may fall below this requirement. The second category, partial legislation, included those states in which legislation had been passed but not yet implemented, did not mandate hearing screening, or did not require complete screening of the newborn population (i.e., only 85% of newborns). States were grouped into this category if they had legislation, but during one or more years of this study (i.e., 2000–2003) the state was not required to screen all infants. The final category, no legislation, consisted of those states in which no UNHS legislation had been passed.

Some states were not categorized and included in the analyses in certain years. There were two reasons for exclusion: (1) having hearing screening data for less than an entire year; and (2) passage or implementation of hearing screening legislation within a particular year, which would have resulted in a state being classifiable into two different categories. The date of implementation was defined as the date when each state reached full compliance with the screening provisions specified in their respective UNHS legislation and/or rules. This abstracted information was verified by state EHDI program personnel and their designated legislative contacts via e-mail.

Because DSHPSHWA data refer to infants' state of birth, regardless of the family's state of residence, we compared these with the number of births occurring in a state during the same year. Births by state of occurrence were obtained from the 2000–2003 natality public use data sets provided by CDC's National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).16 Hearing screening rates were calculated by dividing the number of all infants screened for hearing loss reported in the DSHPSHWA data by the number of births by state of occurrence reported by NCHS.

Screening rates in the implemented-legislation and no-legislation states were compared within each year using a rate ratio and associated asymptotic 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Because the number of children screened in each state and year is a discrete count, we followed standard statistical practice in assuming that the counts follow a Poisson distribution. In addition, trends in rates over time in these two categories were compared, again under the Poisson assumption, using a generalized estimating equation approach (GEE) to account for the likely correlation in state-specific screening rates across years.

We excluded the partial-legislation states from the statistical analyses because of heterogeneity among states in this group. Some states in this group had UNHS legislation that encouraged but did not require screening. Others required screening of just a subset of newborns in the state. Still other states with passed but not yet implemented legislation were included in this group in specific years. As a result, comparison of the average rates observed in this group with those in the other categories (i.e., implemented legislation and no legislation) would be difficult to interpret. Descriptive statistical results are reported for all three groups of states.

For each year, we computed the percentage of states within each category that attained a 95% screening rate. We evaluated differences between the categories (implemented legislation and no legislation) using the ratio of the percentage of implemented-legislation states to the percentage of no-legislation states. The statistical significance of the ratios was examined using 95% asymptotic CIs under the assumption that the number of states reaching the target within a category is a binomial random variable. Trends in the percentages of states reaching a screening rate of 95% were examined using a logistic regression GEE model.

In the second stage of our study, we invited the 13 states without UNHS legislation to participate in a discussion group to examine other factors that could be contributing to the changes in screening rates. EHDI program personnel representing eight states—Alaska, Michigan, Minnesota, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Tennessee, Vermont, and Washington—agreed to participate. We asked them about their perceptions of whether hearing screening had become a standard of care, what factors appeared to be influencing increased screening coverage in their states, and whether they felt that UNHS legislation would be helpful. Following the discussion, we reviewed the transcript and summarized the responses. No discussions were conducted with states that had implemented UNHS legislation.

RESULTS

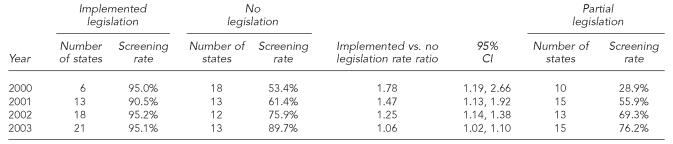

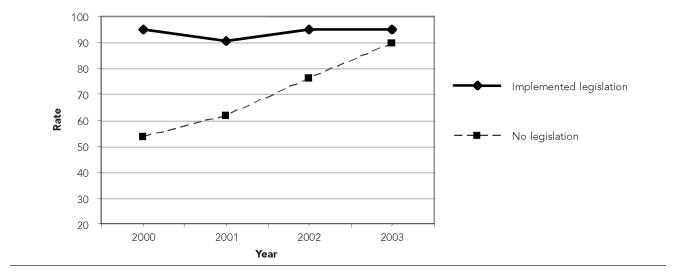

States with implemented legislation had significantly greater screening rates across all years than states with no legislation. However, the difference in the percentage screened between the states with and without implemented legislation decreased across the study period (Table 1). For example, the rate ratio (RR) for implemented-legislation states vs. no-legislation states was RR=1.78 (95% CI 1.19, 2.66) in 2000, in contrast to RR=1.04 (95% CI 1.00, 1.09) in 2003. Comparison by Poisson regression indicated that the screening rates for states with implemented legislation remained constant across years. Conversely, screening rates in the no-legislation groups increased over time (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Screening rates for all categories and rate ratio for implemented vs. no-legislation groups

CI=confidence interval

Figure 1.

Observed screening rates for states with implemented and no legislation

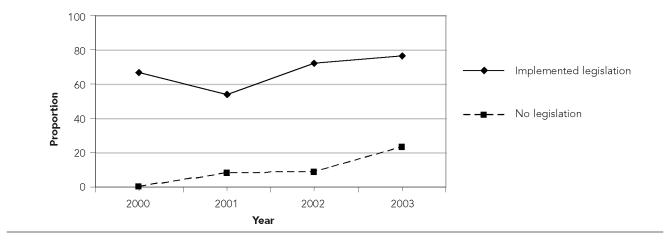

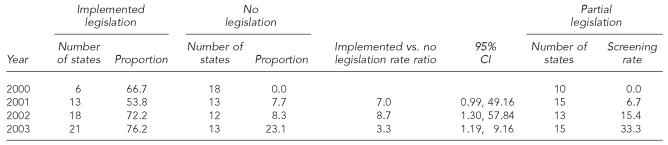

The percentage of states reaching the 95% screening rate benchmark set by the JCIH in 2000 has increased over time in both the legislation and no-legislation groups (Figure 2). Despite this, states with implemented legislation remained significantly more likely to obtain the target. In 2003, 76.2% of the implemented-legislation states reached the 95% screening benchmark, compared with 23.1% of no-legislation states and 33.3% of partial-legislation states (Table 2). The rate ratio for states with implemented legislation vs. states with no legislation decreased over the observed years, but the legislative effect remained significant.

Figure 2.

Observed proportion of states reaching the 95% screening goal

Table 2.

Proportion of states reaching the 95% screening benchmark for all screening categories and risk ratios for implemented vs. no-legislation groups

CI=confidence interval

An analysis of finalized 2004 screening data reinforces the trend observed for 2000–2003. In 2004, states with implemented legislation screened 96.5% of newborns before they reached the age of 1 month compared with 85.7% (RR=1.13; 95% CI 1.05, 1.21) for states with no legislation. In 2004, 85% of states with implemented legislation reached the JCIH 95% screening benchmark compared with 25% (RR=3.40; 95% CI 1.25, 9.22) for states with no legislation and 42.9% for the partial-legislation group.

The discussions with EHDI program personnel from eight states with no legislation revealed a number of factors that were believed to be associated with the widespread increases in hearing screening coverage among newborns. These factors included the availability of federal funding from CDC and HRSA to support state EHDI programs (e.g., development of tracking systems and purchase of screening equipment) and the pressure of competition among birthing facilities to offer the same services in order to attract customers. Other reasons included research findings related to the impact of UNHS and early identification, endorsement by professional organizations, and collaborative relationships with those in the deaf community. Furthermore, program representatives attributed part of their success in increasing screening coverage to the development of collaborative relationships between the state EHDI programs and birthing facilities. There was a consensus that UNHS has become the standard of care in many places, with program staff expressing mixed opinions about the importance of pursuing UNHS legislation in the future.

While opinions of EHDI program personnel are varied on the need to pursue UNHS legislation in the future, most do acknowledge that not having legislation has hindered the implementation of UNHS programs. This was attributed to a lack of state funding for program sustainability and hospitals not being required to report hearing screening results, which in turn was believed to hamper follow-up activities. On the other hand, some suggested that not having legislation was helpful in allowing hospitals to take ownership of the UNHS programs and in preserving collaborative relationships among the state and birthing facilities.

DISCUSSION

Newborn hearing screening is the first step in identifying children with HL. Currently, no federal laws or regulations require universal hearing screening of infants. In the U.S., newborn screening is regarded as a state responsibility. Through its agencies, the federal government provides partial funding and issues recommendations, but states make the decision whether to implement these recommendations. In 2005, the Advisory Committee on Heritable Diseases and Genetic Disorders in Newborns and Children endorsed a report to the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommending that all states adopt newborn screening for a panel of 29 disorders, including hearing loss.17 Although this recommendation has influenced newborn screening panels in a number of states, we are not aware of any impact on state newborn hearing screening policies.

Over two thirds of states have used legislation as a tool to help ensure that newborns are screened for HL soon after birth. However, legislative requirements vary from state to state. The majority of states with UNHS legislation mandate hearing screening, but not all states require that every infant be screened. Based on our analyses, states requiring all infants to be screened have significantly greater screening rates than states with no legislation. We believe that this difference in screening rates is largely attributable to the effect of legislation and that the association between UNHS legislation and screening rates is largely causal, rather than primarily reflecting a tendency for states that would otherwise have had high screening rates to adopt legislation. We acknowledge, though, that we cannot control for unobserved differences among states. Such differences could lead to either overstatement or understatement of the effect of UNHS legislation on screening. Our qualitative research suggests that states that are successful in raising hearing screening rates on a voluntary basis have less incentive to adopt legislation. Consequently, if anything, we believe that the association between legislation and screening could be understated by the joint effects of unmeasured state characteristics on legislation and screening rates.

Although screening rates in states with implemented legislative mandates were significantly higher for all years analyzed than in states with no mandates, the difference decreased over time. This resulted from an increase in screening rates among states with incomplete or no legislation. There is no evidence of a reduction in screening rates among states with fully implemented UNHS legislation. If the positive association observed in earlier years was due to a misleading association because of differences among states in enthusiasm for screening, one would expect late adopters to have lower screening rates. The fact that screening rates among all states with mandates did not decrease over time does not support that hypothesis.

The increased screening in states with no mandate suggests the influence of other factors. Recent publications by Kerschner18 and White19 contend that screening of newborns for HL has become a de facto standard of care. The authors cite a number of factors influencing the adoption of newborn hearing screening practices: the availability of appropriate and relatively inexpensive technology, position papers endorsing UNHS from professional organizations,4,5,12 support from government agencies and advocacy groups, and pressure on practitioners to conform to health care expectations. Likewise, EHDI program personnel from eight states without legislation who were consulted in the second stage of the study agreed that the screening of newborns for HL has become a standard of care in their states.

Although one third of states in the partial-legislation category in 2003 screened at least 95% of infants in their jurisdictions, the mean screening rate was lower than for the no-legislation group. The heterogeneity in this group of states makes it difficult to interpret aggregate statistics. The two largest states in the partial legislation group—California and Texas, which contribute a disproportionate share of births in this category—require only a subset of birthing facilities to screen newborns for hearing loss and to report the results of such screening to the state. It is unclear to what extent other birthing facilities screen infants but do not report results to the state program. Due to underreporting, screening coverage rates for those states would be understated. This could depress overall screening rates for the partial legislation category.

Some states that passed UNHS legislation that does not mandate screening could still have had an impact of legislation on screening. For example, some states have what could be considered “virtual” mandates because of a threat to impose a mandate if voluntary screening does not meet a specified target. In 1997, Colorado became an early adopter of UNHS legislation.13 Colorado's legislation specified that if hospitals did not screen a minimum of 85% of all births by July 1, 1999, the state would promulgate rules requiring that all infants be screened. Their screening rates reportedly increased from 43% in 1997 to 87% in 1999.13 The data in Appendix Table 1 (available from: URL: http://www.publichealthreports.org.) indicate that this increase has continued, rising from 90% in 2000 to 97% in 2002 and 2003.

Legislation is not the only mechanism states have used to create a successful EHDI program. Regulation is another policy instrument that can be used to influence hospital screening practices. A recent article analyzed the evolution of the EHDI program and hearing screening in Michigan, where screening rates were reported to have increased from 23% in 1998 to 92% in 2002.20 Although Michigan has no UNHS legislation, in March 2000 the state Medicaid program began requiring hospitals with more than 15 Medicaid-covered births per year—essentially all birthing centers in the state—to screen infants who were covered by Medicaid. Subsequent to this regulation, all birthing centers, including those that had previously resisted calls to implement universal screening, implemented UNHS programs.

The findings in this study were subject to several limitations. First, many states with UNHS legislation were either not required to screen at all or are required to screen only a portion of their newborn population, making it difficult to compare this group statistically with states in the other screening categories. Second, most states were able to report only estimated hearing screening rates, raising the possibility that screening rates could have been either higher or lower than reported. Third, a few states did not report screening data to DSHPSHWA in one or more of the study years and were not included in the analyses for these years.

A strength of this study is the use of appropriate denominators to calculate newborn hearing screening rates. Our estimate of the national hearing screening rate in 2003 was 86.0% using validated information on births in each state. This compares with a national estimate of 87.9% for 2003 calculated directly from DSHPSHWA data.15 Estimates of hearing screening rates that do not adjust for accurate counts of births in each state can overstate screening coverage, and therefore give an overly optimistic impression of progress toward achieving UNHS goals.

UNHS legislation appears to be an effective tool for helping to ensure that infants are screened for HL, despite the rise in screening rates in states with no UNHS legislation. This is indicated by the significantly higher percentage of states with implemented legislation reaching the 95% screening benchmark. At least 75% of states with implemented legislation reached this target compared with less than 25% of states without legislation in 2003. While other factors undoubtedly affect how many infants are screened, legislation is a tool that could help to raise the national screening level to the 95% screening target.

Should states presently without legislation consider pursuing new UNHS legislation? Although the gap in screening rates has diminished among states without legislation or non-mandatory legislation when compared with those having mandates, states without mandates remain less likely to achieve the benchmark that 95% of all newborns be screened for hearing loss before 1 month of age. It should be noted that state health departments do not have the ability to directly influence whether legislation is adopted. Regardless of which path is pursued, much remains to be done to achieve the national target of 95% of newborns having their hearing screened before 1 month of age.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Coleen Boyle for initiating this study and for providing support and helpful comments. They also thank the staff of state EHDI programs who contributed in various ways to the preparation of this report, including providing data and responding to questions. They acknowledge John Eichwald, Pam Costa, and Esther Sumartojo for providing helpful comments. Finally, they thank TJ Matthews for his assistance in obtaining and interpreting data on numbers of births classified by state of occurrence.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mensah GA, Goodman RA, Zaza S, Moulton AD, Kocher PL, Dietz WH, et al. Law as a tool for preventing chronic diseases: expanding the spectrum of effective public health strategies. Preventing Chronic Disease [serial online] 2004. Jan, [cited 2004 Nov 30]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2004/jan/03_0033.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Stoddard JJ, Farrell PM. State-to-state variations in newborn screening policies. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151:561–4. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170430027005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Therrell BL., Jr. U.S. newborn screening policy dilemmas for the twenty-first century. Mol Genet Metab. 2001;74:64–74. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2001.3238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Early identification of hearing impairment in infants and young children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol; NIH Consensus Development Conference; 1993. pp. 201–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joint Committee on Infant Hearing 1994 position statement. American Academy of Pediatrics Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. Pediatrics. 1995;95:152–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finitzo T, Albright K, O'Neal J. The newborn with hearing loss: detection in the nursery. Pediatrics. 1998;102:1452–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.6.1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Naarden K, Decoufle P, Caldwell K. Prevalence and characteristics of children with serious hearing impairment in metropolitan Atlanta, 1991–1993. Pediatrics. 1999;103:570–5. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoshinaga-Itano C. Early intervention after universal neonatal hearing screening: impact on outcomes. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2003;9:252–66. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.10088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshinaga-Itano C, Sedey AL, Coulter DK, Mehl AL. Language of early- and later-identified children with hearing loss. Pediatrics. 1998;102:1161–71. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.5.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinshaw HM. The pattern of development from non-communicative behaviour to language by hearing impaired and hearing infants. Br J Audiol. 1996;30:177–98. doi: 10.3109/03005369609079039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Children's Health Act of 2000. 2000 Sep 25; Pub. L. No. 106-310. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joint Committee on Infant Hearing; American Academy of Audiology; American Academy of Pediatrics; American Speech-Language-Hearing Association; Directors of Speech and Hearing Programs in State Health and Welfare Agencies. Year 2000 position statement: principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. Pediatrics. 2000;106:798–817. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.4.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehl AL, Thomson V. The Colorado newborn hearing screening project, 1992–1999: on the threshold of effective population-based universal newborn hearing screening. Pediatrics. 2002;109:E7. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerschner JE, Meurer JR, Conway AE, Fleischfresser S, Cowell MH, Seeliger E, George E. Voluntary progress toward universal newborn hearing screening. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;68:165–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Annual DSHPSHWA Data. 2004. [cited 2004 Dec 1]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/ehdi/dips.htm.

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) National Center for Health Statistics. 2000-3 natality files [Google Scholar]

- 17.Health Resources and Services Administration (US) Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders and Genetic Diseases in Newborns and Children [homepage on the Internet] [cited 2005 Oct 26];2005 Available from: URL: http://mchb.hrsa.gov/programs/genetics/committee/ [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kerschner JE. Neonatal hearing screening: to do or not to do. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2004;51:725–36. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White KR. The current status of EHDI programs in the United States. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2003;9(2):79–88. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.10063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ElReda DK, Grigorescu V, Jarrett A. Impact of the Early Hearing Detection and Intervention program on the detection of hearing loss at birth—Michigan, 1998–2002. J Educ Audiol. 2005;12:1–6. [Google Scholar]