SYNOPSIS

Objectives

This study examines whether Alabama's Medicaid family planning demonstration program reaches a different segment of the population than the health department-based Title X family planning program, whether service use rates differ across clients using care within and outside of the Title X provider system, and whether additional risk assessment and care coordination services provided by health department personnel increase the likelihood that family planning clients return for follow-up visits over time.

Methods

Administrative data from four years of operation of the program were used to examine characteristics of the clientele, differences in services used across provider types included in the program, and the impact of risk assessments and care coordination on return visit rates.

Results

The number of family planning service users increased dramatically over the four-year period, but were more similar demographically to Title X clients than to Medicaid maternity clients. Growth was greatest among clients of non-Title X providers. Newly covered services, including risk assessments and care coordination, were available mostly to Title X clients, and these services were associated with a greater likelihood that clients returned for care in subsequent years.

Conclusion

Expanded provider networks can increase the number of low income women using family planning services while risk assessment and care coordination can improve the effectiveness of these services. However, enhanced services may not be equally available across provider systems. Additional outreach efforts are needed to reach women eligible for publicly supported family planning services who are not currently using these services.

Since 1993, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have allowed states to operate demonstration programs that extend Medicaid coverage for family planning services to segments of the population who are likely to be covered by Medicaid in the future if they become pregnant.1,2 These demonstration programs provide coverage for family planning services only; no other types of health care are covered. As of June 2006, eight states extend Medicaid coverage for family planning to women previously covered by Medicaid and 16 other states extend this coverage to all women meeting specific income eligibility criteria.3

Federal and state subsidies already help reduce cost barriers to family planning care for low income populations by supporting the direct provision of these services. Federal subsidies are provided through a grant-in-aid program authorized by Title X of the Public Health Service Act. Health departments are the major provider of publicly funded family planning services, accounting for 43% of the agencies providing such care in 2003.4 However, coverage for family planning through Medicaid programs has the potential to further increase the effective use of family planning services in two ways: by increasing the number and variety of sites of care that are available to the population and by enhancing the services that are provided at family planning visits. With Medicaid coverage, enrollees can seek family planning services from participating providers who are outside of the subsidized Title X family planning provider network. The broader provider network covered by Medicaid may attract segments of the low income population who find it difficult to use Title X services, or who prefer to receive care in physician offices.5,6 In addition, Medicaid coverage for family planning services can be structured to finance selected additional services such as care coordination and patient education. These services have been shown to increase the effectiveness of family planning use among adolescents, and may be applicable to adult populations.7,8 Without explicit financing, it may be difficult to offer these additional services in Title X settings.

One potential negative consequence of Medicaid coverage for family planning is that expanding the service delivery network beyond Title X sites may diminish the range of services actually provided to family planning clients. Research indicates that private physician settings tend to offer fewer counseling and contraceptive services than specialized family planning sites.9,10 A related potential negative consequence is that, with Medicaid coverage available to some portion of their clientele, Title X providers may lose a significant number of clients to other family planning providers, thus diminishing patient revenue that may supplement grant funds in covering operational expenses for the provision of family planning services.

This study used data from the first four years (2000–2004) of Plan First, Alabama's family planning demonstration program, to examine three questions relevant to the Medicaid family planning demonstrations: (1) Do the demonstrations serve more clients and/or a different set of clients than those who used Title X services before Medicaid coverage became available? (2) Do clients within the Medicaid demonstrations who do use Title X providers tend to receive a different set of services than those who use providers outside of this delivery system? (3) Do clients who received the enhanced care coordination service available through the extension use services more consistently over time than clients who do not receive the service?

Plan First extends Medicaid coverage for family planning services to women aged 19–44 with incomes below 133% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) but above the income level that would qualify them for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and full Medicaid coverage (in Alabama, about 15% of the FPL). This is the same group that is eligible for Medicaid coverage for maternity services in the state. In 2004, the Medicaid program covered 26,717, or 45% of all deliveries occurring in Alabama; this indicates that a substantial proportion of women of childbearing age in the state have incomes below 133% of the FPL.11

The Plan First program covers risk assessments for all family planning clients and care coordination services for clients who are categorized as being at high risk for unintended pregnancy, provided by licensed social workers and nurses based in county health departments. Risk assessment interviews include counseling on family planning as well as completion of an assessment tool. Key factors used to determine high risk status include a history of multiple unplanned pregnancies; being a first-time contraceptive user; and having learning and communication difficulties, poor social support systems, or a history of domestic violence or substance use. Care coordination services include appointment reminders, help with transportation, and referrals to other social services and supportive counseling. Any qualified provider may apply to participate in Plan First; a provider's manual contains guidelines for the delivery of comprehensive family planning services.12 Any provider may arrange for care coordination for Medicaid covered clients.

METHODS

We used data from the Medicaid claims and enrollment system to profile the demographics of service users, the types of services used, and visit use over time. We linked Medicaid family planning claims with Medicaid maternity claims to indicate whether Plan First clients entered the demonstration program immediately after a Medicaid covered delivery. We aggregated demographic data on service users separately for the first two years (October 2000 to September 2002) and the second two years (October 2002 to September 2004) of the program, and separately for those who used Title X providers only and those who used a mix of providers or non-Title X providers only. In Alabama, Title X providers are county health departments in all but one county; in one county community health centers also serve as Title X sites. Non-Title X sites include private physician offices, Planned Parenthood facilities, and community health centers. We compared these data to demographic data from the claims of women using maternity services in the year before the start of the Plan First program (October 1999 to September 2000) and to demographic data from the records of clients of Title X clinics in the state in the same pre-Plan First period. To ensure that these groups were comparable in income levels to the Plan First service users, we included only those women eligible for Medicaid through the income expansion (SOBRA) program for the Medicaid maternity data. For Title X clients, we included women up to 133% of the FPL and 80% of the clients included in the category below 50% of the FPL; income determinations below 50% of the FPL are not made for Title X program clients.

We also grouped Plan First service use data in the first two and last two years of the Plan First program, and compared rates of services provided for clients who used (1) only Title X providers, (2) only non-Title X providers, (3) both types of providers, or (4) services that did not require exams and thus were not associated with a provider type. Use rates were shown for risk assessments, care coordination, HIV counseling, tubal ligations, distribution of birth control pills, and provision of Depo Provera injections, based on the procedure codes included on claims paid for these services. Risk assessments are conducted at initial visits by health department nurses or social workers; clients with non-Title X providers can be referred to health departments for risk assessments. Chi-square tests were used to examine whether the frequency of use of different services varied significantly across provider types, but due to large sample sizes, all of the comparisons were statistically significant at the p<0.001 level, even where the differences were not large enough to be meaningful.

We used claims data for the four program years to indicate whether clients had a visit 12 to 24 months, 24 to 36 months, and 36 to 48 months after their initial visit. Visits that did not include claims for exams or contraceptive services were not included in this count, and clients were excluded from the analysis if claims data indicated that they had received a surgical sterilization procedure. Logistic regressions were estimated to examine whether the additional Medicaid covered services, risk assessments, and care coordination provided by county health department personnel in the initial year of program entry increased the likelihood that clients would return over time for family planning care. Other characteristics of the clients are included to adjust as much as possible for factors that also affect the decision to return for care, and return in the later years is modeled separately for clients who did and did not have a family planning visit in the preceding year. Unfortunately, because the data source is administrative data, many characteristics that affect clients' decisions to return for care, such as family structure and economic resources, could not be taken into account.

RESULTS

Overall, client counts for the Alabama Title X program over the four-year period increased from 87,030 to 96,355, an 11% increase. By 2004, the Title X program received reimbursement from Plan First for about 44% of its family planning clients. Plan First evaluation reports for 2004 indicate that an additional 16,337 clients received family planning clinical services outside of the Title X system in that year. This suggests that there was at least a 30% increase in the total number of family planning clients receiving public support for care over the four-year period.

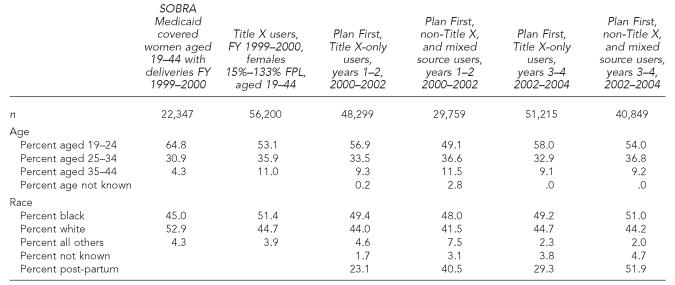

Table 1 compares the demographic profile of four groups of women: those with Medicaid claims for delivery services in the 12 months before the start of Plan First (October 2000), those who used services in the state's Title X clinics in the same time period, those who used services under Plan First in the first two years of the program (October 2000 through September 2002), and those who used services in the second two years of the program (October 2002 to October 2004). Plan First service users are divided into those who used Title X providers exclusively and those who used either only non-Title X providers or a mix of Title X and non-Title X providers. Demographic data are reported only for the Medicaid maternity and Title X clients who fit the age and income criteria of the Plan First program.

Table 1.

Demographic profile of Medicaid paternity, Title X, and Plan First clients

FPL=federal poverty level

The table shows that both the Title X and the Plan First clientele included fewer white and fewer younger women than the Medicaid maternity population. In the later time period, the Plan First clientele were somewhat younger than the earlier cohort of Title X clients, and thus somewhat more like the Medicaid maternity clientele. Overall, there were 39% more total Plan First users in the first two years of the program and 64% more total Plan First users in the second two years of the program than Title X users in that age and income bracket in the year before the start of the demonstration program. However, this is an overestimate of the total increase in clients because the Title X client counts are for one year and the Plan First client counts are for two years.

Clients who used care outside of the Title X system were a little older than clients of Title X providers and were much more likely to be using family planning care after using Medicaid maternity services. The number of women using Title X providers increased by 6% between the first two and the second two years of the program, while the number of women using non-Title X providers or a combination of providers increased by 37%.

Table 2 compares service use among clients across different types of providers. The portion of all Plan First clients who used Title X providers exclusively declined over the four-year period, while the portion using non-Title X providers exclusively increased. Clients of non-Title X providers generally did not receive risk assessments or care coordination services. Non-Title X providers were less likely to provide (or submit a claim for) pre-test and post-test HIV counseling, and they were less likely to provide birth control pills ordered in bulk through the state warehouse. (Plan First does not provide coverage for prescriptions written for contraceptives.) More clients of non-Title X providers received surgical sterilizations because these procedures are provided by physicians rather than Title X clinics. A similar portion of Title X and non-Title X clients received Depo Provera injections.

Table 2.

Comparison of service use by clientele of Title X and non-Title X providers

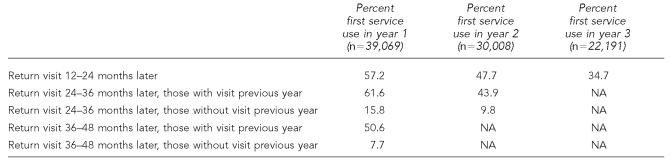

Table 3 shows the portion of women returning for family planning visits over time since their first visit. Generally, about half of clients seen in a year returned in the subsequent year for family planning services. A much smaller portion returned in a year after not using services the previous year. Return rates have declined since the first year of the program.

Table 3.

Portion of clients returning for services over time

NA = not applicable

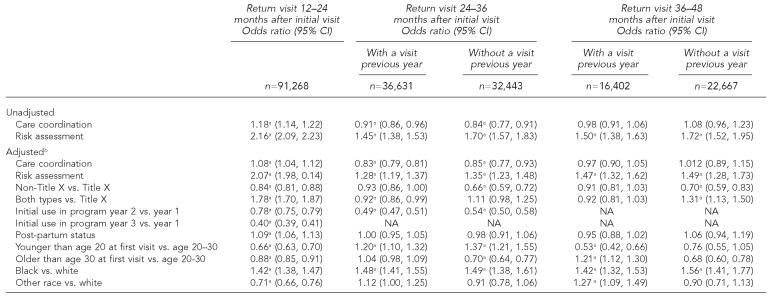

Table 4 shows the findings of unadjusted and adjusted logistic regressions examining the likelihood that service users return for family planning visits in subsequent years. Without controlling for other factors, the additional covered services in the Plan First program—risk assessments and care coordination—increased the likelihood that women returned for a subsequent visit the year after their first visit. In the subsequent years, those who had initially received risk assessments were consistently more likely to return for family planning care, whether or not they had returned the previous year. However, those who had received care coordination in the first year were less likely to return for a visit in the third year, and no more likely than other clients to return for care in the fourth year after their initial visit. Since only high risk clients received care coordination, this may be an indicator that high risk status can be overcome initially but persists over time to diminish women's likelihood to return for family planning care.

Table 4.

Factors associated with return visits: results of logistic regressions

p<0.05

Also adjusted for geographical area of residence in the state.

CI = confidence interval

NA = not applicable

All of these relationships are also observed when other factors are controlled. Other factors positively associated with making a return visit 12 to 24 months after an initial visit were use of both Title X and non-Title X providers (compared to Title X use only), being post-partum (i.e., having a previous Medicaid paid delivery), and being African American rather than white. Factors associated with a lower likelihood of returning for a visit in 12 to 24 months included seeing only non-Title X providers, starting in the second or third year of the program rather than the first year, being younger than age 20 or older than age 30, and being of a race other than white or African American. Subsequent visits 24 to 36 months after the initial visit were more likely for black women and for those younger than age 20 and less likely for those who started the program in the second year, whether or not they had had a visit in the previous year. For those with a visit in the previous year, visits 24 to 36 months after the initial visit were also less likely for users of a mix of Title X and non-Title X providers. For those without a visit in the previous year, visits 24 to 36 months after the initial visit were less likely for those who had initially seen only a non-Title X provider, and for those older than age 30. Subsequent visits 36 to 48 months after the first visit were more likely for black women compared with white women. For those with a visit in the previous year, a subsequent visit at this point was more likely for older women and those of a race other than white or black. Subsequent visits were less likely for those who had been younger than age 20 at the time of the initial visit. For those who had not had a visit in the previous year, this subsequent visit in the third year after the initial visit was less likely for those who had initially seen a non-Title X provider.

DISCUSSION

The availability of Medicaid coverage for family planning services has the potential to increase access and improve the effectiveness of family planning use by low income women. The data presented here for four years of the Alabama demonstration program indicate an increase of more than 30% in the overall publicly funded family planning clientele with the addition of the Medicaid demonstration program. The segment of demonstration participants using services outside of the health department-based Title X system increased to a much greater extent than the segment using only Title X services. This segment of participants tended to be older and to be more likely to have had a Medicaid-funded delivery. Thus, it seems likely that the broader mix of providers available under the Medicaid demonstration program attracted a segment of service users who had not used care under the Title X clinic system. However, the demonstration program did not serve a clientele that was more closely matched to the Medicaid maternity population than the Title X program. Instead, both publicly funded family planning programs had fewer white and younger clients than the Medicaid maternity program.

The data also indicate that one of the newly covered services, risk assessment at the initial visit, had a positive short-term and long-term effect on increasing the likelihood that clients continue to receive family planning services over time. The other newly covered service, care coordination for high risk clients, had a positive short-term effect. Unfortunately, clients of non-Title X providers tended not to receive these services, and were also less likely to receive HIV counseling and birth control pills. Furthermore, use of a non-Title X provider was independently associated with a lower likelihood of returning for continuing family planning care.

There are inherent limitations to the Medicaid claims data used in this study. Services that are not billed are not recorded in the claims system. For example, if non-Title X physicians provided free samples of birth control pills directly to clients rather than requisitioning birth control pills from the state bulk purchase program, or if they provided HIV counseling without billing for a separate service, it is not recorded here. Thus, service provision may be understated and there may be systematic bias to specific provider groups with different billing patterns.

Furthermore, we are unable to identify which Plan First service users gained insurance coverage from other sources over the demonstration period because, by policy during this program period, enrollment in the demonstration program was continuous over the program period and eligibility was not re-checked. Thus, subsequent family planning use may be understated if the services were used but covered by an insurance plan other than Medicaid.

Finally, it is possible that the positive association between receipt of risk assessments and care coordination and return for visits in subsequent years is associated with other unmeasured characteristics of the clients who received these services rather than with the services themselves. We take this into account to some extent by examining the impact of these services separately for those who did and did not return for care in the previous year, and program data suggest that rates of provision of these services in Title X settings depends more on staffing levels at health department clinics than on client characteristics. However, it is possible that generally compliant clients are both more willing to receive risk assessments and care coordination interventions and more likely to return for family planning care over time. In that case, this analysis overstates the ability of these interventions to increase use of family planning care.

Broadening the family planning provider network for low income clients is an important rationale for many of the CMS-approved Medicaid family planning demonstration programs. Evidence examined in the 2003 national evaluation of these programs indicated that several, but not all, of the programs were succeeding in including more different types of providers and more geographically dispersed providers than provided care in the Title X program alone.13 Evidence presented in that evaluation also suggested that many, but not all, demonstration programs were serving many more clients than were served by the Title X program before the demonstration programs began. A survey of all public family planning providers conducted in 2001 also showed that public family planning providers in states with Medicaid demonstration programs, particularly programs that cover women on an income basis, increased the number of clients served since 1994, compared to states without these programs.5 Thus, it is likely that the Alabama experience of increasing family planning clientele through increasing diversity and availability of providers is not unique.

Based on overviews of the currently active Medicaid family planning demonstrations available from CMS,14 only three programs in addition to Alabama (Oklahoma, Mississippi, and Washington) include risk assessment and enhanced follow-up of clients at high risk for unintended pregnancies as covered services. Data presented here, based on the Alabama demonstration program experience, indicate that these services have the potential to increase the effectiveness of family planning service delivery by increasing the likelihood that clients will receive ongoing care. Other Medicaid demonstration programs and other publicly sponsored sources of family planning care for the low income population should consider adding these services as an enhancement to their programs.

In summary, two innovations in the provision of family planning services to low income women are made possible by including this coverage in Medicaid programs: the broadening of the provider network for these services and the financing for enhanced risk assessment and care coordination for clients. These two innovations increase the effectiveness of family planning services and increase the availability of these services to a broader population. Unfortunately, as the program is structured now, the two innovations do not work together. Enhanced services are used primarily by clients of the Title X system, but the majority of new clients use non-Title X providers for services. In addition, neither innovation addresses the underuse of family planning services in the predemonstration Title X program by younger women and white women whose maternity care was financed by Medicaid. Aggressive outreach to this at-risk population would be a useful innovation that could be included as part of any publicly sponsored family planning program.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Frank Mulvihill, PhD, UAB School of Public Health, for excellent support in data analysis.

This project was partially supported through a contract between the UAB School of Public Health and the Alabama Department of Public Health for ongoing evaluation of the Plan First program. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and do not reflect official policies of the Alabama Medicaid Agency or the Alabama Department of Public Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gold RB The Alan Guttmacher Institute. State efforts to expand Medicaid-funded family planning shows promise. The Guttmacher Report on Public Policy. 1999. Apr, [cited 2006 Nov 14]. Available from: URL: http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/tgr/02/2/index.html. [PubMed]

- 2.Schwalberg R, Zimmerman B, Mohamadi L, Giffen M, Mathis SA. Menlo Park (CA): The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2001. Medicaid coverage of family planning services: results of a national survey. Available from: URL: http://www.kff.org/womenshealth/upload/Medicaid-Coverage-of-Family-Planning-Services-Results-of-a-National-Survey-Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guttmacher Institute. State Medicaid family planning eligibility expansions. [cited 2006 Jul 1]. Available from: URL: http://www.guttmacher.org/statecenter/spibs/spib_SMFPE.pdf.

- 4.Lindberg LD, Frost JJ, Sten C, Dailard C. The provision and funding of contraceptive services at publicly funded family planning agencies: 1995–2003. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2006;3(1):37–45. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.037.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frost JJ, Frohwirth L, Purcell A. The availability and use of publicly funded family planning clinics: U.S trends 1994–2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36(5):206–15. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.206.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Radecki SE, Bernstein GS. Use of clinics versus private family planning care by low-income women: access, cost and patient satisfaction. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:692–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.6.692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boardman LA, Weitzen S, Lapane KL. Context of care and contraceptive method use. Women's Health Issues. 2004;14(2):51–9. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finer LB, Darroch JE, Frost JJ. U.S. agencies providing publicly funded contraceptive services in 1999. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2001;34(1):15–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalmuss D, Davidson A, Cohall A, Laroque D, Cassell C. Preventing sexual risk behaviors and pregnancy among teenagers: linking research and programs. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2003;35(2):87–93. doi: 10.1363/3508703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Card JJ, Niego S, Mallari A, Farrell WS. The program on sexuality, health and adolescence: promising “prevention in a box.”. Fam Plann Perspect. 1996;28(5):210–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dagostin CA, Woolbright LA. Montgomery (AL): Division of Statistical Analysis, Center for Health Statistics, Alabama Department of Public Health; 2005. Selected maternal and child health statistics Alabama 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alabama Medicaid Agency Provider Manual 2005. [cited 2006 Nov 21]. Available from: URL: http://www.medicaid.state.al.us/billing/provider_manual.4-05.aspx?tab=6.

- 13.Edwards J, Bronstein JM, Adams EK. Evaluation of medicaid family planning programs. [cited 2006 Nov 12]. Available from: URL: http://images.main.uab.edu/isoph/LHC/BronsteinCMS.pdf.

- 14.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (US) Medicaid waivers and demonstration list. [cited 2006 Jul 14]. Available from: URL: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/MedicaidStWaivProgDemoPGI/MWDL/list.asp.