Abstract

Telomeres are repeated sequences at chromosome ends that are incompletely replicated during mitosis. Telomere shortening caused by proliferation or oxidative damage culminates in replicative arrest and senescence, which may impair regeneration during chronic liver injury. While the effects of experimental liver injury on telomeres have received little attention, prior studies suggest that telomerase, the enzyme complex that catalyzes the addition of telomeric repeats, is protective in some rodent liver injury models. Thus, the aim of this study was to determine the effects of iron overload on telomere length and telomerase activity in rat liver. Mean telomere lengths were similar in iron-loaded and control livers. However, telomerase activity was increased 3-fold by iron loading with no change in levels of TERT mRNA or protein. Because thiol redox state has been shown to modulate telomerase activity in vitro, hepatic thiols were assessed. Significant increases in GSH (1.5-fold), cysteine (15-fold), and glutamate cysteine ligase activity (1.5-fold) were observed in iron-loaded livers, while telomerase activity was inhibited by treatment with N-ethylmaleimide. This is the first demonstration of increased telomerase activity associated with thiol alterations in vivo. Enhanced telomerase activity may be an important factor contributing to the resistance of rodent liver to iron-induced damage.

Keywords: glutamate cysteine ligase, glutathione, hemochromatosis, oxidative stress, telomeres

Introduction

Telomeres are repeated sequences (TTAGGGn) at the ends of chromosomes that are incompletely copied when DNA is replicated during mitosis. In cells lacking a mechanism to restore telomeric sequences, telomeres therefore shorten progressively with each round of cell division. When telomeres reach a threshold length, cells withdraw from the cell cycle and acquire a senescent phenotype. Thus, the inexorable shortening of telomeres with each round of cell division is regarded as a “mitotic clock” that records the number of antecedent cell divisions and signals the onset of phenotypic alterations associated with aging [1,2].

A substantial body of data indicates that telomere attrition is modulated by oxidant-antioxidant balance. For example, human cells cultured under hyperoxic conditions demonstrate accelerated loss of telomeric sequences and diminished replicative capacity compared to cells grown under more physiologic oxygen concentrations, an effect that is attenuated in cell lines with more robust antioxidant capacities [3,4]. Telomere shortening under these circumstances is accompanied by accumulation of single-strand breaks along the telomeres [5], which may reflect the enhanced susceptibility of telomeric sequences to oxidant-mediated cleavage. Data from in vitro studies indicate that the guanine-rich telomeric repeats are preferential sites for sequestration of transition metals that may participate in the generation of the oxidizing species responsible for strand breaks [6] These observations suggest that, along with cell division, oxidative damage is a major factor contributing to telomere shortening.

Conversely, oxidant-antioxidant balance may impact on telomere length through modulation of telomerase activity. Telomerase is a ribonucleoprotein enzyme complex that catalyzes the addition of telomeric repeats to chromosome ends, thereby counteracting the effects of telomere shortening. Although most differentiated human somatic cells lack detectable telomerase activity, germ cells, some stem cells and most cancers possess telomerase activity. Furthermore, unlike humans, adult rodents retain telomerase activity in many differentiated cells types. In the murine 3T3 fibroblast cell line and in some human and rat cancer cell lines, telomerase activity has been shown to be sensitive to thiol redox state, with activity increasing after addition of glutathione or dithiothreitol and decreasing after inhibition of glutathione synthesis or treatment with N-ethylmaleimide [7,8] Taken together with the observations regarding accelerated telomere shortening under conditions of oxidative stress, these data provide evidence that telomere biology may be profoundly affected by oxidant-antioxidant balance. However, as all of these studies have been performed on cultured cells, it is unknown whether such alterations have a similar effect in the whole animal.

Several lines of evidence indicate that telomere shortening may play a role in the evolution of chronic liver disease. This concept is supported by studies demonstrating that the telomeres of chronically diseased human livers are shorter than those of age-matched controls [9–11] Although relatively little work has been done examining the effects of liver injury on telomeres in experimental animals, the available data are intriguing. For example, mice with a targeted deletion of one of the components of telomerase demonstrate impaired hepatic regeneration and accelerated fibrogenesis in the context of liver injury [12]. Consistent with those findings, the livers of rats chronically treated with CCl4 have been reported to show extensive telomere shortening, while both CCl4-induced fibrosis and telomere shortening were attenuated in rats concurrently treated with estrogen, which enhances telomerase expression [13]. Thus, both in rodents and in man, shortening of hepatic telomeres appears to be associated with progressive liver injury and fibrosis.

Hepatic iron overload resulting from hemochromatosis or hematologic disease is an important cause of progressive fibrosis in humans. Although liver damage under these circumstances is presumed to result from iron-catalyzed oxidant production, we have previously reported that in rodent liver, iron overload is associated with upregulation of antioxidant defenses involving thiol metabolism [14,15]. Given that rodent livers are also quite resistant to the fibrogenic effects of chronic iron overload, the aim of this study was to assess the effects of iron loading on hepatic telomere length and telomerase activity. We report here that telomerase activity in rodent liver is significantly increased by iron loading. Steady-state levels of mRNA encoding rat telomerase reverse transcriptase (rTERT), the limiting catalytic subunit of telomerase, are unaffected by iron overload, as are levels of rTERT immunoreactive protein. However, the increase in telomerase activity is associated with significant increase in hepatic glutathione and cysteine levels, and with enhanced glutathione synthetic machinery. These results are the first demonstration of modulation of telomerase activity associated with altered thiol state in a whole animal model.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 200–250 g (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) were individually housed in polyethylene cages with stainless steel tops and were fed a standard rat diet (Dyets, Inc., Bethlehem, PA) and allowed water ad libitum. Iron dextran (50 mg iron per rat for the first 4 injections, 100 mg per rat thereafter) was administered by IP injection every 2 weeks for 6 months as previously described [15]. Control animals received IP injections of an equivalent quantity of dextran on an identical schedule. The animals were cared for in accordance with criteria from the National Research Council and the protocol was approved by the Animal Research Committee of the John Cochran Veterans Administration Medical Center.

Rats (n= 5 per group) were euthanized by exsanguination while anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (65 mg/kg). At the time of death, the livers were quickly excised, weighed and divided for analysis as described below.

Hepatic iron concentration

Nonheme iron concentrations in whole liver were determined by a spectrophotometric method as previously described [15].

Determination of telomere restriction fragment length

Southern analysis of telomere restriction fragment (TRF) length was based on the method of Allsop et al. [16]. Genomic DNA was isolated from 50 mg rat liver using DNeasy Tissue DNA isolation kit (Qiagen, Valencia CA) and quantitated by UV spectrophotometry. Two micrograms of DNA were digested with restriction endonucleases RsaI and HinfI. The DNA digests were electrophoresed through 0.8% agarose and transferred to nylon membranes by capillary transfer in 20X SSC as described [17]. After UV crosslinking (1200μJ), the membranes were hybridized with a 3’-digoxigenin oligonucleotide probe with the sequence (CCCTAA)3. After washing to remove unbound probe, an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-digoxigenin antibody (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) was used for immunodetection of bound probe, followed by CDP Star chemiluminescent substrate (Roche Applied Science). Blots were exposed to X-Ray film for 10–60 seconds. Mean TRF length and % photo-stimulated luminescence were determined from densitometric analysis of digital images of exposed films as described [18]. Measurements of TRF length were performed in duplicate for each liver.

Telomerase activity

Telomerase activity was assayed using a commercial kit (Telo TAGGG Telomerase PCR ELISA, Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, samples of frozen liver (50–100 mg) were homogenized in lysis buffer and protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Because of the presence of inhibitors of the PCR reaction in liver tissue, a preliminary experiment comparing a range of homogenate protein contents was performed; 0.5 μg protein yielded optimal results. Aliquots of homogenate corresponding to this amount of protein were added to the reaction mixtures and incubated at 25º C for 30 mins to allow endogenous telomerase to add TTAGGG repeats to the substrate. After heat inactivation of the enzyme, the samples were subjected to 30 cycles of PCR amplification. The PCR products were then denatured and hybridized to a digoxigenin-labeled oligonucleotide probe containing the telomeric repeat sequence. The hybridization mixture was transferred to streptavidin-coated microtiter plates and peroxidase-conjugated anti-digoxigenin antibody was used to detect PCR products by ELISA. All samples were assayed in triplicate. A lysate of HEK293 cells was used as a positive control; telomerase activity was abolished in heat-inactivated rat liver homogenate (65ºC x 10 min) that served as negative control. To provide a qualitative confirmation of the results of the ELISA, reaction products from the telomerase activity assay were also analyzed by electrophoresis in nondenaturing 12% polyacrilamide gels in 1X TBE. The gels were stained with SYBR Green (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and visualized by UV illumination.

Quantitation of rat TERT expression by real-time PCR

Real-time quantitation of rat telomerase reverse transcriptase gene (rTERT) expression was assessed using the TaqMan Gene Expression Assay with an rTERT probe which spans the exon1-exon2 boundary (position 223) of reference sequence NM001007019 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and 18S as a control amplification target. Samples were assayed in triplicate after preliminary experiments confirmed similar amplification efficiencies for rTERT mRNA and 18S PCRs. The amount of mRNA was calculated using the comparative Ct method and is expressed as 2−ΔΔCt.

Immunoprecipitation of rat TERT

Liver lysates were prepared by homogenization on ice of ~100mg tissue in non-denaturing lysis buffer containing 1mM sodium orthovanadate and 10 μl/ml (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The hepatocyte cell line WRL68, which is known to express TERT, was used as a positive control. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). For each sample, 1 μg polyclonal anti-TERT antibody (sc7212), Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) was incubated with a volume of lysate corresponding to 500 μg protein for 16 hours at 4°C on a rocker, followed by addition of 25 μl of 25% suspension of protein A-agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The samples were then incubated for 5 hrs at 4°C on a rocker. The immunoprecipitates were collected by centrifugation, followed by washing with non-denaturing lysis buffer. The pellets were suspended in Western sample buffer and stored at −20°C until they were analyzed by Western blot.

HPLC analysis of thiol pools

Reduced glutathione, cysteine, and γ-glutamyl cysteine pools were analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as previously described [15]. Glutathione and thiol content were quantified against appropriate standard curves and normalized per mg protein.

Glutamate cysteine ligase activity

Glutamate cysteine ligase (GCL) activity was determined using an HPLC method [19] Sample γ-glutamylcysteine (GGC) levels were determined using a standard curve, normalized per mg protein and plotted versus time. GCL activity was reported as nmol GGC mg−1 min−1.

Western blots

Homogenates of liver were prepared in ice-cold RIPA buffer (50 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mmol/L NaCl, 0.25% (w/v) sodium deoxycholate, I mmol/L EDTA, I mmol/L sodium orthovanadate and 10 μl/ml (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Immunoblotting was performed using a polyclonal antibody against GCL heavy chain (Neomarkers, Lab Vision Corp., Fremont, CA) diluted 1:2,000, followed by peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG diluted 1:2,500 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). After extensive washing, bound antibody was detected using chemiluminescence according to the manufacturer’s instructions (ECL; Amersham Biosciences UK Ltd., Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK).

Statistical analysis

Variables were compared by t-tests with the exception of hepatic iron concentrations which were analyzed by Mann-Whitney rank sum test because they were not normally distributed. The effects of varying doses of N-ethylmaleimide on telomerase activity was assessed by ANOVA. Correlations between telomerase activity and other parameters was assessed by Spearman’s correlation coefficients. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Effect of iron loading

After administration of iron dextran for 6 mos, median hepatic iron concentrations of the iron-loaded rats were increased nearly 60-fold compared to the control animals (10706 vs 189 μg/g, p<0.001). On histological examination, no inflammation, necrosis or fibrosis was evident in either the iron-loaded livers or the controls; histochemical staining for non-heme iron demonstrated granular iron deposition within hepatocytes and large sinusoidal iron deposits as previously reported [15].

Effect of iron loading on telomere length

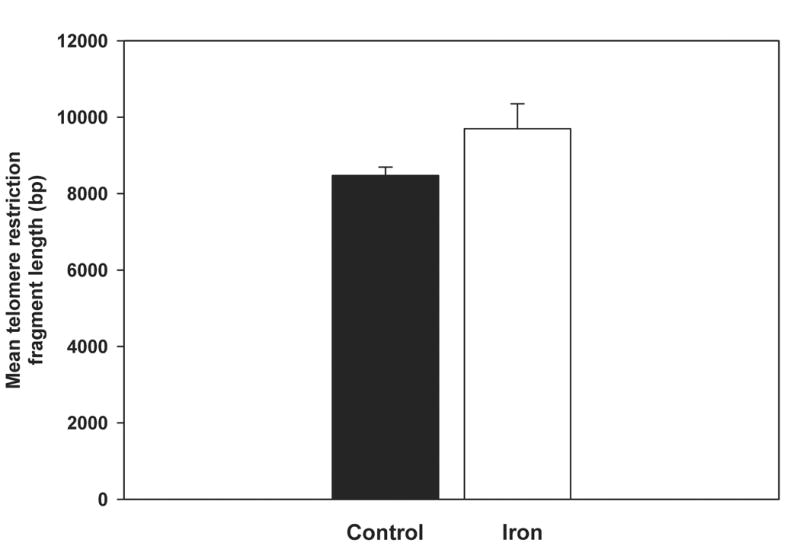

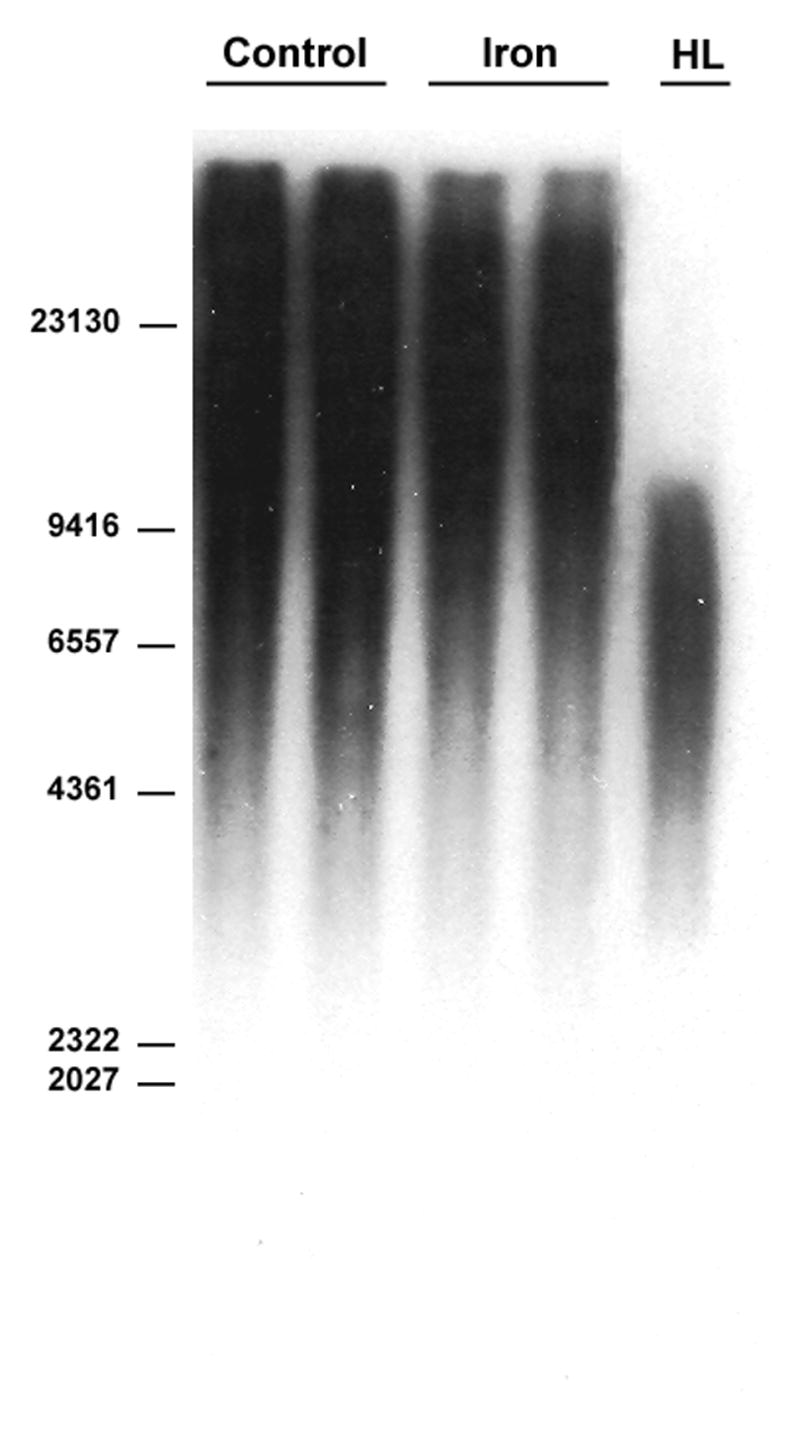

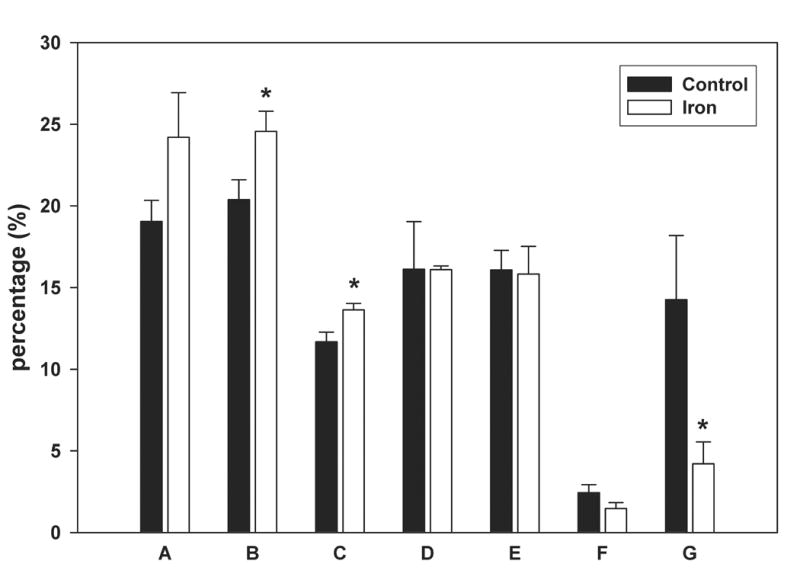

Telomere length was calculated by two different methods. The first method assesses mean telomere length. The second method evaluates the distribution of telomere lengths, on the premise that the presence of critically shortened telomeres which are biologically significant may not be reflected by mean telomere lengths [18]. No difference in mean telomere length was observed between the control and iron-loaded livers (Fig. 1A,B). Overall, the distribution of telomere lengths were similar between the two groups, however, the iron-loaded livers tended to have fewer telomeres in the shortest range (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Mean telomere restriction fragment length in control and iron-loaded livers was determined by Southern analysis as described in the Methods. A. No significant difference was observed between the mean telomere lengths of the control and iron-loaded livers. B. Representative Southern blot of liver telomere restriction fragments. Location of the base pair markers on the DNA ladder is indicated along the left side. The lanes labeled “control” and “iron” are duplicate digests of DNA from individual control and iron-loaded livers, respectively. “HL” is a digest of DNA from a cirrhotic human liver for comparison. C. Comparison of the distribution of telomere restriction fragment lengths showing that the iron-loaded livers have a smaller proportion of very short telomeres; asterisks indicate statistical significance (p<0.05). Letters under bars indicate range of telomere restriction fragment sizes (base pairs); “A” ≥ 23130; “B,” 23129-9416; “C,” 9415-6557; “D,” 6556-4361; “E,” 4360-2322; “F,” 2321-2027; “G,” 2026-564.

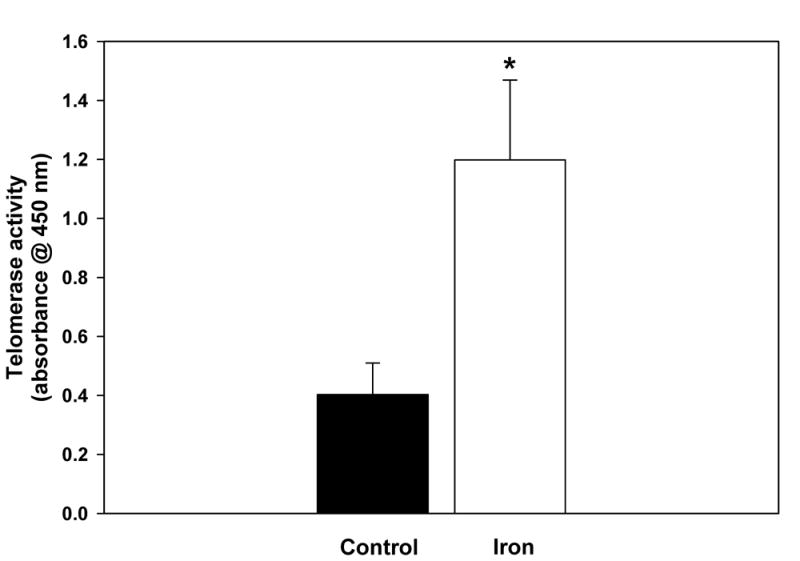

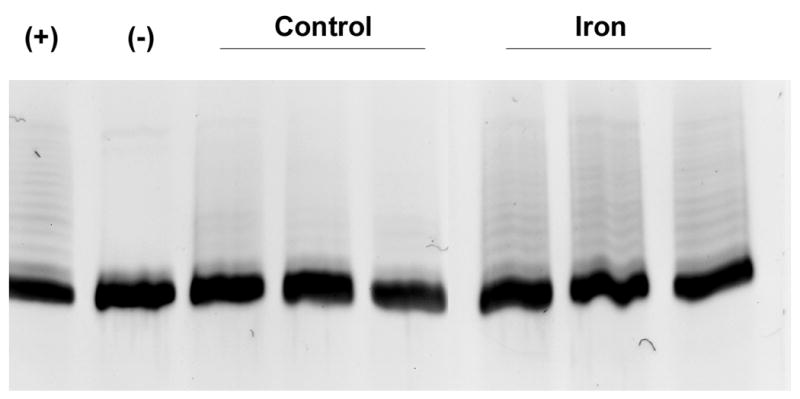

Effect of iron loading on telomerase activity

Given that we and others have demonstrated that iron overload is associated with increased hepatocyte proliferation [20–22], which would be expected to cause telomere shortening, the finding that telomere lengths were not dramatically altered by iron loading suggested that telomerase activity might be increased in the iron loaded livers. Indeed, telomerase activity in the iron-loaded livers was increased 3-fold relative to control livers (p<0.05), in which there were detectable but rather low levels of telomerase activity, consistent with previous reports (Fig. 2). To determine whether telomerase activity is modulated by excess iron, an experiment was performed in which telomerase activity was assayed after addition of FeSO4 to homogenates of control rat livers to produce iron concentrations comparable to those in the iron-loaded livers. Telomerase activity was not altered by the addition of exogenous iron to the control homogenates (data not shown), indicating that the increase in telomerase activity seen in the iron-loaded livers was not a direct effect of excess iron on the enzyme.

Figure 2.

Telomerase activity in homogenates of control and iron-loaded livers was determined by telomerase activity assay described in the Methods. A. Telomerase activity was significantly increased in the iron-loaded livers (p<0.05). B. The increase in telomerase activity measured by ELISA (above) was confirmed by electrophoresis and staining of the assay reaction products, demonstrating increased intensity of the “ladders” (representing telomeric repeats) in iron-loaded livers. The lane labels are as follows: “+” indicates positive control (lysate of HEK293 cells), “−“ indicates negative control (heated-inactivated liver lysate), “control” indicates lysates from 3 separate control livers, “iron” indicates lysates from 3 separate iron-loaded livers.

To investigate the mechanism of enhanced telomerase activity in the iron-loaded livers, real-time PCR measurement of rat TERT transcripts was performed to determine whether the transcript abundance for this critical telomerase subunit is altered by iron loading. However, no significant differences in the steady-state levels of rTERT mRNA were observed between the iron-loaded livers and the controls. We next attempted to evaluate the abundance of rTERT in whole liver homogenates by immunoblot; however, rTERT was not detectable by this method, likely because of its low abundance. In order to enhance its detection, rTERT was first immunoprecipitated, followed by immunoblotting. Densitometric quantitation of rTERT demonstrated by these means yielded no significant difference between the controls and iron-loaded livers (not shown). Thus, the increase in telomerase activity in the iron-loaded livers does not appear to be explained by either a transcriptional or translational mechanism affecting rTERT, and suggests that post-translational regulation of enzyme activity may be altered by iron loading.

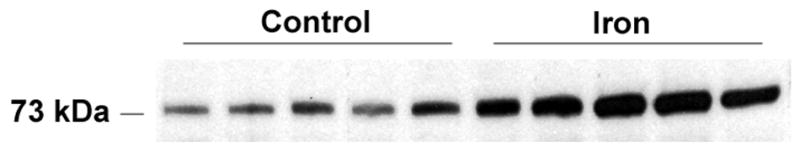

Effect of iron loading on hepatic glutathione metabolism

Glutathione and other reductants have been reported to enhance telomerase activity in vitro. We have previously observed that iron loading elicits alterations in hepatic glutathione and in thiol pools, suggesting an enhanced capacity for glutathione synthesis. These parameters were therefore assessed. Hepatic glutathione levels were significantly increased in the iron-loaded livers compared to controls (Table 1). Similarly, levels of γ-glutamyl cysteine were elevated in the iron-loaded livers, while cysteine levels were dramatically increased by iron loading. Consistent with the interpretation that these changes represent an upregulation of glutathione synthetic pathway in the iron-loaded livers, the activity of glutamate cysteine ligase (GCL), the rate-limiting enzyme in GSH synthesis, was significantly increased in the iron-loaded livers compared to controls (1,423 ± 184 versus 996 ± 145 fmol/min/μg protein, p<0.005). The increase in GCL activity was associated with increased abundance of the GCL catalytic (heavy) subunit in the iron-loaded livers, as assessed by Western blot (Fig. 3). Densitometric quantitation of the blot confirmed a mean 1.8-fold increase in immunoreactive GCL catalytic subunit in the iron-loaded livers compared to control livers. The observed increase in telomerase activity demonstrated highly significant correlations with cysteine and GCL activity (Table 2), suggesting that these parameters might play a role in the modulation of telomerase activity in the iron-loaded livers..

Table 1.

Reduced glutathione, γ-glutamyl cysteine, reduced cysteine content and glutamate cysteine ligase activity in control and iron-loaded livers.

| Treatment | GSH nmol/mg pro | γ-glutamyl cysteine nmol/mg pro | Cysteine nmol/mg pro | GCL activity fmol/min/μg pro |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 74 ± 26 | 0.02 ± 0.03 | 0.54 ± 0.28 | 996 ± 145 |

| Iron | 108 ± 10* | 0.11 ± 0.07* | 8.50 ± 4.75† | 1423 ± 184† |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD for n = 5 per group.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

Figure 3.

Expression of glutamate cysteine ligase catalytic (heavy) subunit is significantly increased in iron-loaded liver. Western analysis was performed as described in the Methods.

Table 2.

Spearman correlation coefficients between telomerase activity and hepatic iron concentration, GSH, cysteine, γ-glutamyl cysteine and glutamate cysteine ligase activity. Units for all parameters are as given in Materials and methods.

| Telomerase activity vs: | ||

|---|---|---|

| r | p | |

| Hepatic iron concentration | 0.915 | <0.0001 |

| GSH | 0.482 | 0.148 |

| Cysteine | 0.860 | <0.0001 |

| γ-glutamyl cysteine | 0.353 | 0.292 |

| Glutamate cysteine ligase | 0.795 | <0.004 |

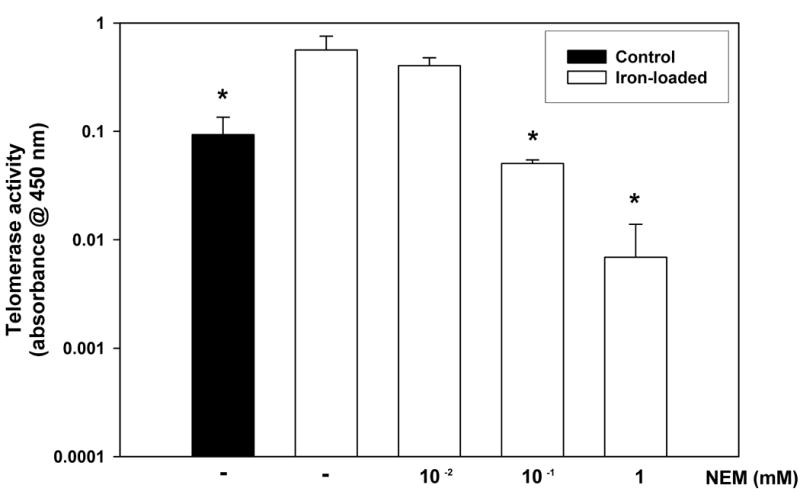

To test the relationship between alterations in the availability of reduced thiols and telomerase activity in the iron-loaded livers, we performed an experiment in which homogenates from the iron-loaded livers were treated with N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), a thiol alkylating agent, prior to assaying telomerase activity. As shown in Fig. 4, NEM inhibited telomerase activity in iron-loaded homogenates in a dose-dependent manner. At a dose of 0.1mM NEM, telomerase activity in iron-loaded liver was similar to that of control liver.

Figure 4.

Diminished availability of reduced thiols decreases telomerase activity in iron-loaded liver homogenates. Iron-loaded liver homogenates were treated with varying doses of the thiol alkylating agent, N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) and telomerase activity measured using the telomerase activity assay described in the Methods. Treatment with NEM dose-dependently reduced telomerase activity in the iron-loaded samples (p<0.05 by ANOVA). A control liver homogenate is included for comparison.

Discussion

Although a great deal has been learned about telomeres from studies of cultured human cells, less is known about the biology of telomeres in vivo. Relatively little attention has been paid to the effects of disease models on telomeres in rodents, perhaps because of the known differences in telomere length and telomerase activity among human and rodent species [18,23–26]. Notwithstanding the species differences, data implying a pathogenic role of telomere shortening in several forms of human pathology suggest that assessment of the effects of disease models on rodent telomeres may provide important insights into the relationship between telomeres and disease processes.

Thus, the goal of the current work was to evaluate the effects of iron overload on telomeres in rat liver. Mitosis and oxidative damage are major causes of telomere erosion. Given that iron is both a direct mitogen in the liver, as well as a potential source of prooxidants, we predicted that iron overload would cause telomere shortening. Surprisingly, however, there was no significant difference in mean telomere length between the iron-loaded livers and the controls. Furthermore, the iron-loaded livers actually had fewer of the shortest telomeres. These observations suggested that iron loading modifies telomerase activity, a prediction confirmed by the finding that telomerase activity is significantly increased in the iron-loaded livers.

A variety of mechanisms have been implicated in the regulation of telomerase activity. In general, there is a close correlation between telomerase activity and expression of the telomerase catalytic subunit, TERT [27]. Most differentiated human somatic cells lack both telomerase activity and TERT expression, while germ cells, some stem cells and a majority of cancers demonstrate both telomerase activity and TERT expression. In contrast, many tissues of adult rodents, including the liver, show persistent telomerase activity and TERT expression [23–26]. Consistent with these data, we observed a low level of telomerase activity and TERT expression in control rat livers. However, the elevated telomerase activity in the iron-loaded livers was not accompanied by an increase in the abundance of TERT mRNA or protein, indicating that post-translational mechanisms may be involved in the enhanced enzymatic activity.

A variety of post-translational mechanisms are reported to modulate telomerase activity including phosphorylation, nuclear translocation and protein-protein interactions. Phosphorylation of human TERT by Akt/protein kinase B, as well as by several isoforms of protein kinase C, is reported to activate telomerase [28,29]. These signaling pathways are implicated in the modulation of telomerase activity by cytokines, which may also enhance nuclear translocation of TERT via interactions with NF-κB [30,31]. Similarly, interaction of TERT with Hsp90 appears to be required for telomerase activity [29,32]. In preliminary studies, we have found no evidence that hepatic iron overload activates the Akt pathway (22) or increases Hsp90 expression (data not shown). Thus, although we cannot at present exclude a role for other signaling pathways, it seems unlikely that either Akt-mediated phosphorylation or induction of Hsp90 accounts for the increase in telomerase activity associated with iron loading.

A plausible explanation for the increase in telomerase activity in the iron-loaded livers is that it results from iron-induced alterations in glutathione and thiol metabolism. As reported here and in previous work, iron loading stimulates upregulation of the glutathione synthetic machinery. The increase in telomerase activity observed in the iron-loaded livers is accompanied by elevated levels of cysteine, γ-glutamyl cysteine and glutathione as well as increased activity of the rate-limiting enzyme, glutamate cysteine ligase. Prior studies in cultured fibroblasts have shown that telomerase activity is enhanced by a high ratio of glutathione/glutathione disulfide or in the presence of chemical reducing agents, while activity is decreased following treatment with buthionine sulfoximine, an inhibitor of glutathione synthesis [7,8]. Consistent with these data, treatment of iron-loaded liver homogenates with NEM, which decreases the availability of reduced thiols, also reduces telomerase activity. Although this does not exclude the possibility that other mechanisms contribute to the enhancement of telomerase activity by iron loading, these observations indicate that telomerase activity in liver homogenates is indeed sensitive to modulation by thiol redox state. Further studies are needed to determine whether modulation of glutathione and/or thiol metabolism is sufficient to alter hepatic telomerase activity in vivo.

We have previously proposed that alterations in glutathione and thiol metabolism are adaptations involved in protection against iron-induced toxicity. Given that telomere shortening and/or impaired telomerase activity have been linked to the development of progressive fibrosis in chronic liver injury [9–12], it is likely that enhanced telomerase activity serves a protective function. One means by which telomerase may confer protection during chronic liver injury is through the prevention of telomere shortening with its resultant replicative arrest and senescence. Hepatocyte proliferation is a common feature of chronic liver injury, including iron overload, and senescent hepatocytes are observed in cirrhotic human livers [33]. Although the ability of hepatocytes to proliferate is well known, this capacity appears to require adequate telomere length and/or telomerase activity, since liver regeneration is impaired after partial hepatectomy in telomerase-deficient mice [34]. These observations suggest that induction of telomerase activity in the face of chronic proliferative stimulation may be an adaptive response that prevents critical shortening of telomeres leading to cellular senescence.

Hepatocyte apoptosis is also a common feature of chronic liver injury that has been implicated in the pathogenesis of progressive fibrosis [35]. Telomerase expression is reported to enhance resistance to apoptotic cell death in a variety of cell types, including those in which apoptosis is stimulated by exposure to oxidants [36–41]. Although the precise mechanisms accounting for resistance to apoptosis have not been elucidated, this effect of telomerase may be important in experimental liver injury. Further studies are needed to determine whether the iron-induced increase in telomerase activity modulates apoptosis and, if so, whether this alters the fibrogenic response to iron.

In conclusion, this is the first study to assess the effects of chronic iron overload on rat liver telomeres. Despite the mitogenic and potential prooxidant effects of iron, iron overload did not dramatically alter hepatic telomere length. However, iron loading elicited a significant increase in telomerase activity that was associated with enhanced glutathione synthesis. Given that chronic iron overload fails to induce progressive fibrosis in rats, these observations suggest that responses involving upregulation of glutathione metabolism as well as telomerase activity may represent important protective mechanisms against iron-induced liver damage.

Footnotes

The authors thank Drs. Al Klingelhutz and James Martin for their helpful advice on the measurements of telomeres and telomerase activity.

KEB was supported by a Merit Review grant from the Veterans Administration. WNS was supported by NIH R21-DK068453-01A1. DRS was supported by NIH grants RO1-CA100045 and P30-CA086862.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wong JMY, Collins K. Telomere maintenance and disease. Lancet. 2003;362:983–988. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14369-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blasco MA. Telomeres and human disease: ageing, cancer and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:611–622. doi: 10.1038/nrg1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Zglinicki T, Saretzki G, Döcke W, Lotze C. Mild hyperoxia shortens telomeres and inhibits proliferation of fibroblasts: a model for senescence? Exp Cell Res. 1995;220:186–193. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.von Zglinicki T, Serra V, Lorenz M, Saretzki G, Lenzen-Grossimlighaus R, Gessner R, Risch A, Steinhagen-Thiessen E. Short telomeres in patients with vascular dementia: an indicator of low antioxidative capacity and a possible risk factor? Lab Invest. 2000;80:1739–1747. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von Zglinicki T, Pilger R, Sitte N. Accumulation of single-strand breaks is the major cause of telomere shortening in human fibroblasts. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28:64–74. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henle ES, Han Z, Tang N, Rai R, Luo Y, Linn S. Sequence-specific DNA cleavage by Fe2+-mediated Fenton reactions has possible biological implications. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:962–971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borrás C, Esteve JM, Viña JR, Sastre J, Viña J, Pallardó FV. Glutathione regulates telomerase activity in 3T3 fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 279(33):34332–34335. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402425200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayakawa N, Nozawa K, Ogawa A, Kato N, Yoshida K, Akamatsu K, Tsuchiya M, Nagasaka A, Yoshida S. Isothiazolone derivatives selectively inhibit telomerase activity from human and rat cancer cells in vitro. Biochemistry. 1999;38:11501–11507. doi: 10.1021/bi982829k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kitada T, Seki S, Kawakita N, Kuroki T, Monna T. Telomere shortening in chronic liver diseases. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1995;211:33–39. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aikata H, Takaishi H, Kawakami Y, Takahashi S, Kitamoto M, Nakanishi T, et al. Telomere reduction in human liver tissues with age and chronic inflammation. Exp Cell Res. 2000;256:578–582. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiemann SU, Satyanarayana A, Tsahuridu M, Tillmann HL, Zender L, Klempnauer J, Flemming P, Franco S, Blasco MA, Manns MP, Rudolph KL. Hepatocyte telomere shortening and senescence are general markers of human liver cirrhosis. FASEB J. 2002;16:935–942. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0977com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rudolph KL, Chang S, Millard M, Schreiber-Agus N, DePinho RA. Inhibition of experimental liver cirrhosis in mice by telomerase gene delivery. Science. 2000;287:1253–1258. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5456.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sato R, Maesawa C, Fujisawa K, Wada K, Oikawa K, Takikawa Y, Suzuki K, Oikawa H, Ishikawa K, Masuda T. Prevention of critical telomere shortening by oestradiol in human normal hepatic cultured cells and carbon tetrachloride induced rat liver fibrosis. Gut. 2004;53:1001–1009. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.027516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown KE, Kinter MT, Oberley TD, Freeman ML, Frierson HF, Ridnour LA, Tao Y, Oberley LW, Spitz DR. Enhanced γ-glutamyl transpeptidase expression and selective loss of CuZn superoxide dismutase in hepatic iron overload. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998;24:545–555. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00284-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown KE, Dennery PA, Ridnour LA, Fimmel CJ, Kladney RD, Brunt EM, Spitz DR. Effect of iron overload and dietary fat on indices of oxidative stress and hepatic fibrogenesis in rats. Liver Int. 2003;23:232–242. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2003.00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allsopp RC, Vaziri H, Patterson C, Goldstein S, Younglai EV, Futcher AB, Greider CW, Harley CB. Telomere length predicts replicative capacity of human fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1992;89:10114–10118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. Analysis of DNA sequences by blotting and hybridization; pp. 2.9.2–2.9.5. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cherif H, Tarry J, Ozanne S, Hales C. Ageing and telomeres: a study into organ- and gender-specific telomere shortening. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:1566–1583. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ridnour LA, Sim JE, Choi J, Dickinson DA, Forman HJ, Ahmad IM, Coleman MC, Hunt CR, Goswami PC, Spitz DR. Nitric oxide induced resistance to hydrogen peroxide stress is a glutamate cysteine ligase activity dependent process. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:1361–1371. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stål P, Hultcrantz R, Möller L, Eriksson LC. The effects of dietary iron on initiation and promotion in chemical hepatocarcinogenesis. Hepatology. 1995;21:521–528. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840210237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whittaker P, Dunkel VC, Bucci TJ, Kusewitt DF, Thurman JD, Warbritton A, Wolff GL. Genome-linked toxic responses to dietary iron overload. Toxicol Pathol. 1997;25:556–564. doi: 10.1177/019262339702500604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown KE, Mathahs MM, Broadhurst KA, Weydert J. Chronic iron overload stimulates hepatocyte proliferation and cyclin D1 expression in rodent liver. Trans Res. 2006;148:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martín-Rivera L, Herrera E, Albar JP, Blasco MA. Expression of mouse telomerase catalytic subunit in embryos and adult tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95: 10471–10476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Golubovskaya VM, Presnell SC, Hooth MJ, Smith GJ, Kaufmann WK. Expression of telomerase in normal and malignant rat hepatic epithelia. Oncogene. 1997;15:1233–1240. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamaguchi Y, Nozawa K, Savoysky E, Hayakawa N, Nimura Y, Yoshida S. Change in telomerase activity of rat organs during growth and aging. Exp Cell Res. 1998;242:120–127. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muira M, Karasaki Y, Abe T, Higashi K, Ikemura K, Gotoh S. Prompt activation of telomerase by chemical carcinogens in rats detected with a modified TRAP assay. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1998;246:13–19. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu J-P. Studies of the molecular mechanisms in the regulation of telomerase activity. FASEB J. 1999;13:2091–2104. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.15.2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kang SS, Kwon T, Kwon DY, Do SI. Akt protein kinase enhances human telomerase activity through phophorylation of telomerase reverse transcriptase subunit. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13085–13090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haendeler J, Hoffmann J, Rahman S, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Regulation of telomerase activity and anti-apoptotic function by protein-protein interaction and phosphorylation. FEBS Lett. 2003;536:180–186. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akiyama M, Hideshima T, Hayashi T, Tai Y-T, Mitsiades CS, Mitsiades N, Chauhan D, Richardson P, Munshi NC, Anderson KC. Cytokines modulate telomerase activity in a human multiple myeloma cell line. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3876–3882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akiyama M, Hideshima T, Hayashi T, Tai Y-T, Mitsiades CS, Mitsiades N, Chauhan D, Richardson P, Munshi NC, Anderson KC. Nuclear factor-κB p65 mediates tumor necrosis factor α-induced nuclear translocation of telomerase reverse transcriptase protein. Cancer Res. 2003;63:18–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Forsythe HL, Jarvis JL, Turner JW, Elmore LW, Holt SE. Stable association of hsp90 and p23, but not hsp70, with active human telomerase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:15571–15574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100055200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paradis V, Youssef N, Dargère D, Bâ N, Bonvoust F, Deschatrette J, Bedossa P. Replicative senescence in normal liver, chronic hepatitis C, and hepatocellular carcinomas. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:327–32. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.22747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Satyanarayana A, Wiemann SU, Buer J, Lauber J, Dittmar KEJ, Wüstefeld T, Blasco MA, Manns MP, Rudolph KL. Telomere shortening impairs organ regeneration by inhibiting cell cycle re-entry of a subpopulation of cells. EMBO J. 2003;22:4003–13. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Canbay A, Freidman S, Gores GJ. Apoptosis: the nexus of liver injury and fibrosis. Hepatology. 2004;39:273–278. doi: 10.1002/hep.20051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holt SE, Glinsky VV, Ivanova AB, Glinsky GV. Resistance to apoptosis in human cells conferred by telomerase function and telomere stability. Mol Carcinog. 1999;25:241–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu C, Fu W, Mattson MP. Telomerase protects developing neurons against DNA damage-induced cell death. Dev Brain Res. 2001;131:167–171. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(01)00237-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ren J-G, Xia H-L, Tian Y-M, Just T, Cai G-P, Dai Y-R. Expression of telomerase inhibits hydroxyl radical-induced apoptosis in normal telomerase negative human lung fibroblasts. FEBS Lett. 2001;488:133–138. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02397-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gorbunova V, Seluanov A, Pereira-Smith OM. Expression of human telomerase (hTERT) does not prevent stress-induced senescence in normal human fibroblasts but protects the cells from stress-induced apoptosis and necrosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38540–38549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202671200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luiten RM, Pène J, Yssel H, Spits H. Ectopic hTERT expression extends the life span of human CD4+ helper and regulatory T-cell clones and confers resistance to oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. Blood. 2003;101:4512–4519. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu L, Trimarchi JR, Navarro P, Blasco MA, Keefe DL. Oxidative stress contributes to arsenic-induced telomere attrition, chromosome instability, and apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31998–32004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303553200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]