Abstract

Ly49A is an inhibitory receptor, which counteracts natural killer (NK) cell activation on the engagement with H-2Dd (Dd) MHC class I molecules (MHC-I) on target cells. In addition to binding Dd on apposed membranes, Ly49A interacts with Dd ligand expressed in the plane of the NK cells' membrane. Indeed, multivalent, soluble MHC-I ligand binds inefficiently to Ly49A unless the NK cells' Dd complexes are destroyed. However, it is not known whether masked Ly49A remains constitutively associated with cis Dd also during target cell interaction. Alternatively, it is possible that Ly49A has to be unmasked to significantly interact with its ligand on target cells. These two scenarios suggest distinct roles of Ly49A/Dd cis interaction for NK cell function. Here, we show that Ly49A contributes to target cell adhesion and efficiently accumulates at synapses with Dd-expressing target cells when NK cells themselves lack Dd. When NK cells express Dd, Ly49A no longer contributes to adhesion, and ligand-driven recruitment to the cellular contact site is strongly reduced. The destruction of Dd complexes on NK cells, which unmasks Ly49A, is necessary and sufficient to restore Ly49A adhesive function and recruitment to the synapse. Thus, cis Dd continuously sequesters a considerable fraction of Ly49A receptors, preventing efficient Ly49A recruitment to the synapse with Dd+ target cells. The reduced number of Ly49A receptors that can functionally interact with Dd on target cells explains the modest inhibitory capacity of Ly49A in Dd NK cells. This property renders Ly49A NK cells more sensitive to react to diseased host cells.

Keywords: cis interaction, immune synapse, inhibitory receptor

Natural killer (NK) cells can kill certain transformed and infected host cells. Target cell recognition requires conjugate formation and the engagement of activating, costimulatory, and inhibitory receptors on NK cells. Target cell lysis occurs when the integrated positive signals exceed those transmitted by inhibitory NK cell receptors. Crucial negative regulators of NK cell effector functions are members of the human killer Ig-like receptor (KIR) and mouse Ly49 receptor families, which bind MHC class I molecules (MHC-I) on target cells (1). Ly49A, the prototype inhibitory MHC-I receptor in the mouse, binds H-2Dd (Dd) and Dk molecules on target cells, whereas the binding to Db or Kb is below detection (2, 3).

In addition to the classical interaction with MHC-I on neighboring cells, a large fraction of the Ly49A receptors are bound to Dd expressed in the plane of the NK cells' membrane (cis interaction). Multivalent, soluble Dk complexes bound Ly49A inefficiently when NK cells expressed Dd, which was readily reversed on the disruption of MHC-I complexes on living NK cells (4). Even though Dd and Ly49A are physically associated in cis, Ly49A NK cells from Dd mice are functional (4), implying that cis interaction does not mediate constitutive, cell-autonomous inhibitory signaling. Indeed, Ly49A is not constitutively phosphorylated when expressed in the context of Dd (L.S. and W.H., unpublished data).

The crystal structure of the Ly49A/Dd complex together with site-directed mutagenesis analyses revealed that Ly49A-mediated NK cell inhibition (trans interaction) depends on a lateral binding site, which is located beneath the peptide-binding platform of Dd (5–7). The same binding site was found to mediate Ly49A/Dd cis interaction (4). Nevertheless, it was recently proposed that cis and trans complexes are distinct (8). In the Ly49A/Dd cocrystal, the Ly49A homodimer had a closed conformation and was associated with a single Dd molecule (5). In contrast, an open dimer conformation was observed in solution, and this form was able to bind two Dd molecules (8). Thus, it was proposed that trans complexes include two and cis complexes a single Dd molecule (8).

To understand the role of cis interaction for NK cell biology, it is crucial to know whether Ly49A is stably masked by cis Dd or whether Ly49A can switch from a cis- to a trans-bound state during target cell interaction as initially proposed in ref. 9. Unmasking could occur based on early NK cell activation signals and/or via a competition between trans and cis ligand for Ly49A binding. In fact, there is a precedent for the latter scenario: CD22 on B cells is largely inaccessible to soluble, multivalent sialoside probes because of CD22 interaction in cis with α2-6-linked sialic acids (10). Notwithstanding, CD22 readily redistributes to the site of cell–cell contact in a trans ligand-dependent fashion, implying that trans ligands efficiently compete with cis ligands for CD22 binding on cellular interaction (11). Accordingly, if Dd cis and trans ligands compete for Ly49A binding, this could serve to set a threshold for inhibitory signaling in NK cells. Alternatively, cis ligand may preclude binding of Ly49A to trans ligand, consequently reducing the number of Ly49A receptors, which are available to functionally interact with trans ligand. This would serve to permanently lower the threshold at which NK cell activation exceeds NK cell inhibition. To discriminate between the two possibilities, we determined the extent of Ly49A recruitment to synapses with Dd+ target cells, depending on the expression of Dd on the NK cell.

NK cell/target cell conjugate formation chiefly depends on leukocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1)-mediated adhesion (12). In addition, LFA-1 engagement provides early activation signals, particularly in IL-2-cultured NK cells (13). Interestingly, the dynamics of conjugate formation/maintenance differs between lytic and inhibitory interactions (14). Specifically, inhibitory interactions by human NK cells show reduced conjugate formation compared with lytic ones, suggesting that KIR function limits cellular adhesion (15, 16). Stable conjugation leads to the formation of supramolecular structure (called an immunological synapse) at the site of NK cell/target cell contact. Lytic and inhibitory interactions correlate with spatially and temporally distinct relocalization of activating and inhibitory signaling molecules to the synapse (17, 18). Ligand binding is sufficient to induce the reciprocal clustering of MHC-I on target cells and human inhibitory KIR (19–21) or mouse Ly49A on NK cells (22). This redistribution of inhibitory KIR occurs independent of receptor signaling (20, 21). In contrast, KIR signaling via Src homology region 2 domain-containing phosphatase-1 recruitment is required to prevent the sustained transduction of NK cell activation signals and protect target cells from lysis (20, 23–25). Although these events have been extensively studied by using human NK cells, very little information is available about the behavior of murine Ly49 receptors. Here, we determined whether the NK cells' Dd, via an interaction with Ly49A in cis, impacted the formation of NK cell/target cell conjugates and the relocalization of Ly49A to the cellular contact site. The magnitude of these effects was compared with the binding of soluble multivalent Dd complexes to Ly49A.

Results

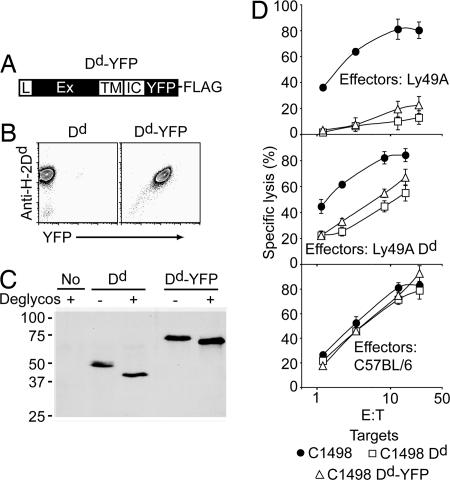

Generation of H-2Dd-Enhanced Yellow Fluorescent Protein (EYFP)-Expressing Tumor Target Cells.

To facilitate the investigation of NK cell/target cell interaction, we stably expressed an H-2Dd-EYFP (Dd-YFP) fusion protein in C1498 tumor cells (H-2b) (Fig. 1A). H-2Dd (Dd) expression, as assessed with mAb staining, correlated with YFP fluorescence (Fig. 1B), and the transfectants expressed a single Dd species at the cell surface, which was compatible with the predicted size of the Dd-YFP fusion protein (Fig. 1C). Thus, YFP fluorescence can be used to trace the localization of Dd protein.

Fig. 1.

H-2Dd-EYFP transfectants. (A) Schematic representation of the H-2Dd-EYFP (Dd-YFP) fusion protein. L, leader peptide; Ex, extracellular; TM, transmembrane; IC, intracellular domain of Dd; YFP, enhanced yellow fluorescent protein. (B) Analysis of YFP and Dd expression (using mAb 34-2-12) by using flow cytometry. (C) Dd was immunoprecipitated (using mAb 34-2-12) and either left untreated (−) or subjected to deglycosylation (+) before immunoblotting with an anti-class I Ab. (D) 51Cr release assays by using IL-2-expanded NK cells from Ly49A Tg, Ly49A × Dd Tg, and non-Tg C57BL/6 NK cells as effectors against C1498, C1498 Dd, and C1498 Dd-YFP target cells. E:T, effector-to-target cell ratio.

Functional experiments showed that lysis of C1498 cells depends in part on NKG2D engagement (data not shown) and that Dd or Dd-YFP expression completely prevented the lysis by Ly49A transgenic (Tg) NK cells (Fig. 1D). Lysis was restored on Ly49A blocking by using mAb (data not shown). NK cells from Ly49A Dd Tg mice efficiently killed C1498 Dd or Dd-YFP cells (Fig. 1D), and Ly49A blockade led only to a minor further increase of target cell lysis (data not shown). Parental C1498 cells were lysed to the same extent independent of whether Ly49A NK cells expressed Dd (Fig. 1D). These data are in agreement with our previous findings (4) and validate C1498 Dd-YFP cells for further use in functional assays and imaging.

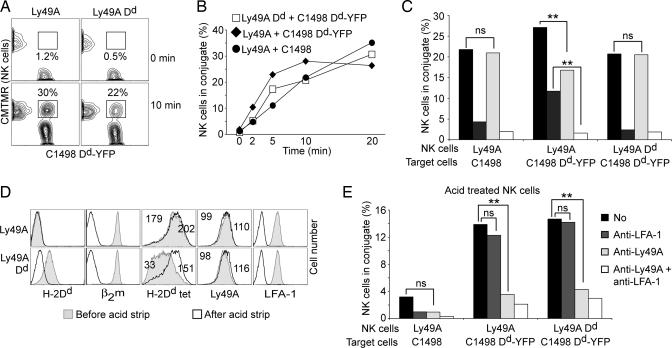

Conjugate Formation by Ly49A and Ly49A Dd NK Cells.

The differential lysis of C1498 Dd target cells could be explained if Ly49A (in the absence of Dd from NK cells) reduced the capacity to adhere to Dd+ target cells, similar to some observations with human KIR (21, 26). Alternatively, Dd expression by NK cells may lower the Ly49A-dependent inhibitory signal. We first tested the efficacy of Ly49A and Ly49A Dd NK cells to form conjugates with Dd-YFP target cells at 37°C. Inhibitory conjugates (Ly49A effectors with Dd-YFP targets) formed more efficiently compared with lytic interactions (all other combinations) (Fig. 2 A and B). However, at a later time point (20 min), lytic conjugates were at least as abundant as inhibitory ones. Thus, the inhibitory interaction (Ly49A effectors with Dd-YFP targets) correlates with conjugates forming rapidly yet being less sustained compared with interactions leading to lysis. Thus, unlike human KIR (21, 26), Ly49A seems to contribute rather than to reduce conjugate formation.

Fig. 2.

Conjugate assays. (A) Conjugate formation between Ly49A Tg or Ly49A Dd Tg NK cells [labeled with 5-(and -6)-(((4-chloromethyl)benzoyl)amino)tetramethylrhodamine (CMTMR)] and C1498 Dd-YFP target cells, at 0 and 10 min of incubation at 37°C. Numbers indicate the percentage of NK cells conjugated with Dd-YFP cells. (B) Abundance of NK cell/target cell conjugates at different time points of incubation at 37°C. Each data point represents the mean percentage of NK cells forming conjugates from five or more independent determinations. (C) Abundance of conjugates at 10 min at 37°C, in the absence of mAb (No) or in the presence of anti-LFA-1 and/or anti-Ly49A mAbs. Bars show the mean of six independent experiments. Statistically significant differences between selected data sets are indicated as follows: ∗∗, P < 0.01; ns, not significant (P > 0.3). (D) Histograms show overlays of untreated (gray fill) and acid-treated NK cells (open histograms) stained with anti-Dd (34-2-12), anti-LFA-1 (121/7), anti-β2-microglobulin (β2m) (S19.8), anti-Ly49A (JR9) mAbs or with PE-labeled Dd multimers. Numbers indicate the geometric mean before and after acid treatment. (E) Conjugate formation by using acid-treated NK cells in the absence of mAb (No) or in the presence of anti-LFA-1 and/or anti-Ly49A mAbs. The bars show the mean of four independent assays. Statistically significant differences are indicated as follows: ∗∗, P < 0.01; ns, not significantly different (P > 0.3).

LFA-1 blockade prevented the formation of conjugates between Ly49A NK cells and C1498 targets (Fig. 2C). In contrast, Ly49A NK cells retained substantial adherence to Dd-YFP cells on LFA-1 blockade (Fig. 2C). In this case, adhesion was mediated in part by Ly49A because the combined blockade of Ly49A and LFA-1 was required to abrogate conjugate formation (Fig. 2C), explaining why such conjugates formed more efficiently. Interestingly, LFA-1 blockade was sufficient to abrogate conjugate formation between Ly49A Dd NK cells and Dd-YFP targets. Blocking of Ly49A had no effect (Fig. 2C), suggesting that Dd expression by NK cells prevented Ly49A from contributing to adhesion.

To determine whether Ly49A masking by cis Dd was responsible for the above effect, we disrupted MHC-I complexes on the surface of living NK cells by using a mild acid treatment (4). Acid exposure very efficiently destroyed trimolecular MHC-I complexes as judged by the quantitative loss of β2-microglobulin staining (Fig. 2D). Concomitantly, the treatment of Dd-positive (but not Dd-negative) NK cells unmasked Ly49A because H-2Dk (4) and H-2Dd multimer binding to Ly49A significantly improved (Fig. 2D). In addition, acid treatment affected LFA-1 integrity as assessed by mAb binding (Fig. 2D). Indeed, adhesion to Dd-YFP cells was reduced by 40–70%, irrespective of whether Ly49A NK cells expressed Dd or not (Fig. 2, compare E with C). Importantly, however, the residual conjugate formation was now Ly49A-dependent also for Dd-expressing NK cells (Fig. 2E). In agreement with these data, acid-treated Ly49A NK cells essentially failed to adhere to Dd-negative C1498 cells (Fig. 2E). The inability to kill Dd+ C1498 cells is thus not related to a reduced formation of conjugates with Ly49A NK cells. On the contrary, the experiments reveal that Ly49A actually contributes to target cell adhesion. However, the NK cells' own Dd restricts the adhesive function of Ly49A via receptor masking.

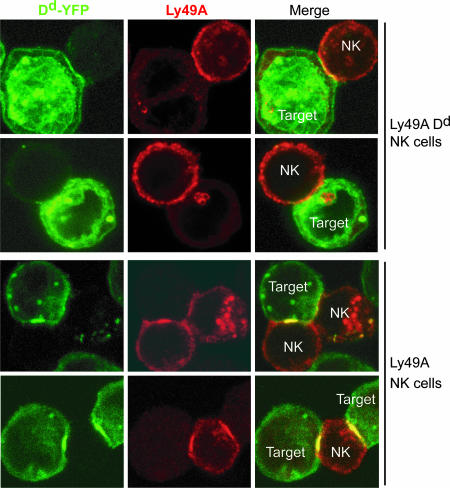

cis Association Limits the Redistribution of Ly49A to the Synapse.

The conjugate formation experiments indicate that cis Dd prevents Ly49A from efficiently interacting with trans Dd. If so, cis Dd might impact Ly49A redistribution to the immunological synapse, which is driven by Dd ligand expression on target cells. To test this possibility, we used confocal microscopy to determine Dd-YFP (on target cells) and Ly49A accumulation at the site of NK/target cell contact (Fig. 3). The majority of conjugates (45%) with Ly49A NK cells showed an evident central accumulation of Dd-YFP on the target cell. In contrast, central Dd-YFP accumulation was rare (5.5%) in conjugates with Ly49A Dd NK cells. Rather, most of these synapses exhibited either scattered clusters (39%) or no evident (55%) accumulation of Dd-YFP at the site of interaction (Figs. 3 and 4A). In all instances, Ly49A distribution mirrored that of Dd-YFP.

Fig. 3.

Recruitment of Ly49A and its ligand to the synapse. Ly49A Tg and Ly49A Dd Tg NK cells were conjugated with C1498 Dd-YFP targets for 10 min before fixation and staining with anti-Ly49A mAb (JR9). Images are maximum intensity projections of a series of confocal acquisitions. Dd-YFP fluorescence is shown in green; Ly49A staining is shown in red; and in merged images, yellow indicates colocalization.

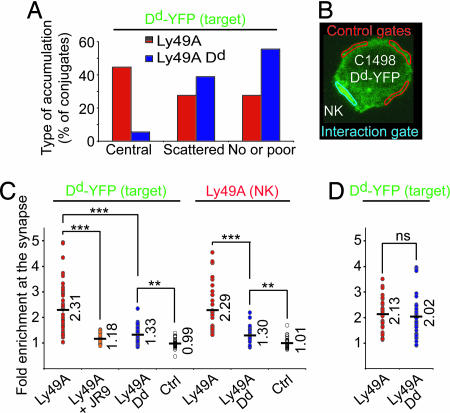

Fig. 4.

cis interaction restricts the recruitment of Ly49A to the synapse. Ly49A Tg and Ly49A Dd Tg NK cells were conjugated with C1498 Dd-YFP targets, fixed, and stained for Ly49A. (A) Conjugates (n > 34) were differentiated according to the extent and appearance of Dd-YFP distribution at the synapse. (B) The enrichment of Dd-YFP (and Ly49A) at the synapse was quantified by comparing the mean fluorescence intensity in the interaction gate (at the contact site) to that of control gates. Values >1 indicate enrichment at the synapse. (C) Enrichment of Dd-YFP (Left) and Ly49A (Right) at the synapse. Each symbol represents an individual conjugate. As a control, Ly49A Tg NK cells were preincubated with an anti-Ly49A mAb (+JR9). Unconjugated cells were used to determine whether Dd-YFP or Ly49A distribution was even (enrichment = 1) in the absence of cell–cell contact (Ctrl). The number of conjugates quantified was as follows: n = 42, 20, 35, 35, 27, 23, and 30 (from left to right). Numbers and horizontal bars depict the geometric mean. (D) NK cells were briefly exposed to an acidic buffer before conjugation with target cells and quantification of Dd-YFP fluorescence enrichment at the synapse. n = 33 for both Ly49A and Ly49A Dd NK cells. Statistically significant differences are indicated as follows: ∗∗, P < 0.01; ∗∗∗, P < 0.001; ns, not significantly different (P > 0.3).

To quantify the extent of Ly49A or Dd-YFP enrichment at the site of NK cell/target cell interaction, we compared the fluorescence intensity at the interaction site to that of control gates on the same cell (Fig. 4B). Cells on the same slide, which made no contact with other cells, were used as a reference. As expected, the mean factor of enrichment was very close to 1, indicating homogenous Ly49A or Dd-YFP distribution on the cell surface in the absence of cell–cell contact (Fig. 4C). In contrast, Ly49A NK cells in contact with Dd-YFP target cells showed an extensive enrichment of Ly49A (2.29-fold) or Dd-YFP (on target cells) (2.31-fold) at the site of interaction. Blocking Ly49A by using mAb strongly reduced Dd-YFP relocalization, demonstrating that ligand accumulation at the cellular interface requires Ly49A engagement. Importantly, conjugates with Ly49A Dd NK cells showed considerably less Ly49A (1.30-fold) or Dd-YFP accumulation (1.33-fold) (Fig. 4C). Notwithstanding, Ly49A recruitment by using Ly49A Dd NK cells was still significantly above that of control cells (P < 10−5). These data show that the extent of Ly49A relocalization to the NK/target cell interface is significantly reduced in Dd-expressing NK cells.

We next tested whether the accumulation of Ly49A at the cellular interface was limited because of the masking of Ly49A by cis Dd. MHC-I complexes on NK cells were disrupted as above, and the redistribution of Dd-YFP molecules on target cells was monitored (Fig. 4D). Compared with untreated NK cells, acid exposure of Ly49A Dd NK cells significantly enhanced the accumulation of Dd-YFP (from 1.33- to 2.05-fold enrichment) at the site of interaction. In fact, the extent of Dd-YFP accumulation now corresponded well to that seen with acid treated (2.13-fold) or untreated (2.31-fold) Ly49A NK cells. Thus, the NK cells' own Dd, via an interaction with Ly49A in cis, determines the extent of Ly49A redistribution to the target cell contact site.

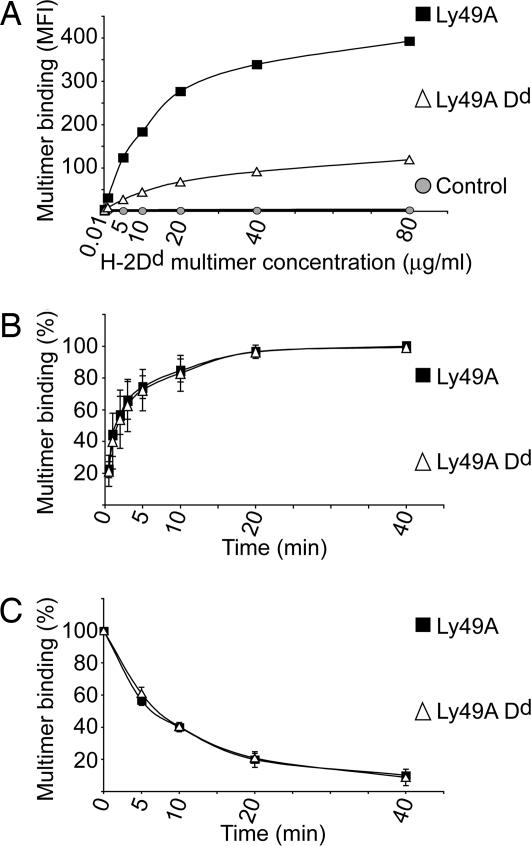

In NK/target cell conjugates, Dd-YFP relocalization is ≈4-fold reduced (i.e., from 2.31- to 1.33-fold whereby the “background” of 1.0 is subtracted) when Ly49A NK cells express Dd (Fig. 4C). We next tested whether the reaction of Ly49A NK cells with multivalent soluble Dd complexes produced comparable effects and/or whether there was evidence for Ly49A unmasking by soluble ligand. The staining of Ly49A NK cells with increasing concentrations of Dd multimer at 37°C reached a plateau, whereby maximal multimer binding was reduced 3- to 3.5-fold in the presence of Dd on NK cells (Fig. 5A). This difference was essentially abolished on acid stripping (Fig. 2D). The kinetics of Dd multimer binding to Ly49A and the decay were not altered in the presence of Dd on NK cells (Fig. 5 B and C). This is consistent with the view that the Dd multimer does not efficiently compete with cis Dd for Ly49A binding.

Fig. 5.

Binding and dissociation of soluble, multivalent Dd complexes. (A) Ly49A Tg and Ly49A Dd Tg NK cells were reacted with increasing concentrations of PE-labeled Dd multimer at 37°C. C57BL/6 NK cells, negatively gated for endogenous Ly49A (control), were used as negative control. The graph shows the geometric mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of PE staining versus the Dd multimer concentration. (B) Kinetics of Dd multimer (40 μg/ml) binding to Ly49A Tg and Ly49A Dd Tg NK cells at 37°C. Maximal multimer binding to either type of NK cells at 40 min (=100%) was used for normalization. (C) Ly49A Tg and Ly49A Dd Tg NK cells were stained with Dd multimer (40 μg/ml) at 4°C (MFI at 0 min = 100%), and the decay of the bound multimer at 37°C was estimated over time. Multimer rebinding was prevented by the addition of the anti-Ly49A mAb A1 (20 μg/ml). Data in B and C represent the mean (±SD) of three independent experiments.

Finally, we used the anti-Ly49A mAb A1, which specifically binds to ligand-accessible Ly49A receptors (4), to block free Ly49A receptors on Dd NK cells. Subsequent Dd multimer binding would require the unmasking of cis-bound Ly49A. Preincubation with mAb A1 efficiently prevented Dd multimer binding to Ly49A at 4°C (91.4 ± 2.4% blocking). The blocking was somewhat less efficient when the Dd multimer staining was done at 37°C (71.7 ± 7.7% blocking). However, this was not because of Ly49A unmasking because identical effects were seen in the absence of Dd from NK cells (89.2 ± 6.8 and 74.0 ± 5.4% blocking at 4 and 37°C, respectively). Indeed, the dissociation of mAb A1 from Ly49A NK cells readily accounted for the increased multimer staining at 37°C (data not shown). We conclude that neither soluble Dd multimer nor cell-bound Dd ligand is able to efficiently compete with cis Dd for Ly49A binding. Therefore, cis Dd constitutively reduces the number of Ly49A receptors, which can functionally interact with MHC-I ligand on target cells.

Discussion

To elucidate the precise role of Ly49A/Dd cis interaction for NK cell function, we analyzed the impact of the NK cells' Dd on target cell recognition by Ly49A NK cells. We show that the NK cells' Dd prevents Ly49A-dependent cell–cell adhesion and strongly reduces the redistribution of Ly49A and the target cells' Dd to the site of cell contact. The destruction of Dd complexes on NK cells, which unmasks Ly49A, is required and sufficient to reverse these effects. These observations strongly suggest that Ly49A/Dd cis complexes are stable, such that a considerable fraction of Ly49A receptors remains inaccessible during target cell interaction. The extent of residual Ly49A relocalization in the presence of cis Dd is in good agreement with the amount of free Ly49A expressed on such NK cells. These findings, together with the functional data, show that the potential activity of Ly49A as a negative regulator of NK cell function is constitutively lowered via receptor sequestration by MHC-I ligand expressed on the NK cell surface.

An adhesive function of Ly49 receptors has been noted before. Indeed, Ly49 receptors transfected into xenogeneic cell lines mediate adhesion to lymphoblasts or tumor cells. This has been used to investigate the ligand specificity of Ly49A and other Ly49 family receptors (3, 27, 28). In contrast, KIRs do not seem to enhance cellular adhesion (21, 26). Similarly, we find that Ly49A does not measurably contribute to cell–cell adhesion when NK cells coexpress Dd, which is mediated by Ly49A/Dd interaction in cis. The lack of Ly49A-dependent adhesion in the syngeneic situation (i.e., when both the NK cell and the target cell express Dd) may serve the useful purpose to prevent Ly49A NK cells from preferentially interacting with healthy Dd+ host cells. Our findings also provide an explanation for the observation that Ly49A Dd NK cells do not efficiently acquire Dd from neighboring cells (29).

In addition, we show that in the presence of Dd in cis a majority of Ly49A receptors are inert to Dd trans ligand-driven accumulation at the NK/target cell interface. These data provide strong evidence that Ly49A/Dd cis interaction remains stable in the context of target cell recognition. This conclusion is supported by the differential binding of soluble, multivalent Dd complexes to Ly49A and Ly49A Dd NK cells. Thus, there is no evidence that trans ligand can out-compete cis ligand, suggesting that Ly49A does not switch from a cis- to a trans-bound state on target cell interaction, as initially proposed in ref. 9. The lack of displacement is consistent in principle with a model in which cis complexes include a single Dd molecule and where structural clashes preclude the binding of an additional Dd molecule to the Ly49A homodimer (5, 8). We have proposed that cis interaction was enabled via considerable flexibility of the Ly49A stalk, which allowed the back folding of the ligand-binding domain relative to the NK cell membrane. In contrast, we hypothesized that trans interaction required an extended stalk conformation (4). It is thus possible that the back-folded Ly49A form is relatively stable and, even on dissociation from cis Dd, does not readily switch to an extended conformation. In this way, the rebinding in cis would be favored, and trans ligand could not readily compete with cis Dd for Ly49A binding.

The apparent stability of Ly49A/Dd cis interaction contrasts with the reversal of CD22/sia cis interaction during cell–cell contact (11). Indeed, soluble, high-avidity CD22 ligands can effectively compete with and replace CD22 cis ligands (30). It is thus thought that CD22 cis ligands determine the binding to biologically relevant trans ligands by setting a competitive binding threshold (30). In contrast to CD22, we have no evidence that the ratio of cis bound to free Ly49A does significantly change during target cell interaction or the incubation with multivalent ligand. However, this does not mean that the number of ligand-accessible Ly49A receptors is always the same. It is conceivable that this can vary during NK cell development and/or in the context of a particular cellular environment. This could occur via changes in the expression of Ly49A and/or MHC-I genes. For example, an increase of MHC-I gene expression may enhance Ly49A sequestration and consequently further reduce the availability of Ly49A receptors. Such modifications may be useful to further fine-tune NK cell function.

Based on the findings reported herein, we propose that Ly49A/Dd cis interaction adjusts Ly49A function to the inherited self-MHC-I environment. This adaptation is relevant for the NK cell's capacity to react to diseased host cells. For example, tumor cells constitutively expressing NKG2D ligand and retaining Dd expression are not killed as they should when Ly49A function is not adjusted (Fig. 1D) (4). Hence, cis interaction renders Ly49A+ NK cells useful to react to abnormal host cells. The NK cells' functional adaptation is based on the fact that the MHC-I expressed by NK cells corresponds to that of their environment. Thus, NK cell function is adjusted to the MHC-I environment via a cell-autonomous calibration of Ly49A receptor function.

Materials and Methods

Mice, Cell Culture, and Chromium Release Assays.

C57BL/6 (B6) (H-2b) mice were obtained from Harlan OLAC (Zeist, The Netherlands). Ly49A and H-2Dd Tg mice have been described (31, 32). All transgenic mice have been backcrossed at least 10 times to the C57BL/6 background. NK cell culture conditions, acid stripping, and 51Cr release assays have been described (4). NK cell preparations used in these experiments have been cultured in human IL-2 (500 ng/ml) for 3–6 days. For antibody blocking experiments, effector cells were preincubated for 20 min at 4°C with mAb JR9-318 (anti-Ly49A) or an isotype-matched control (mAb MR11.1, anti-TCRVβ8) at a concentration of 10 μg per 106 effector cells.

Transfectants.

C1498 and C1498 H-2Dd have been described (4). A plasmid encoding EYFP attached to the C terminus of H-2Dd was constructed by inserting a EYFP PCR product containing SalI sites in between H-2Dd and a C-terminal FLAG tag in a modified pEF BOS expression vector (4). Stable C1498 transfectants were generated as described (4).

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot Analysis.

For immunoprecipitation, transfectants were reacted with 20 μg/ml anti-Dd mAb (34-2-12) before washing and cell lysis as described (4). Immunoprecipitates were denatured in 1% SDS at 100°C for 3 min. Deglycosylation was done according to manufacturer's instructions by using 0.5 units of Endoglycosidase F/N-Glycosidase F (Roche Diagnostics, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) at 37°C for 16 h before Western blot analysis by using rabbit anti-pan-class I antibodies (R218) (kindly provided by F. Levy, Ludwig Institute, Lausanne, Switzerland).

Flow Cytometry.

For surface staining of transfectants and NK cells, the following reagents were obtained from PharMingen (San Diego, CA) unless otherwise indicated: 34-2-12 (anti-Dd), JR9-318 (termed JR9 herein) (anti-Ly49A; kindly provided by J. Roland, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France), A1 (anti-Ly49A; kindly provided by J. Allison, Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY), 145-2C11 (anti-CD3ε), PK136 (anti-NK1.1), M17/4 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) or 121/7 (anti-LFA-1) (Caltag–Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and S19.8 (anti-β2-microglobulin). These mAbs were conjugated to phycoerythrin (PE), FITC, PE-Cy5.5, Alexa 647, or PerCP-Cy5.5 fluorochromes. Dd multimers were refolded by using mouse β2-microglobulin and the HIV-derived peptide RGPGRAFVTI by using standard techniques (33). Nylon wool nonadherent splenocytes or cultured NK cells (0.5–1 × 106) were stained with anti-NK1.1 and CD3 mAbs before incubation with the indicated concentration of the PE-labeled Dd multimer. Samples were run on a FACScan or FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA), and data were analyzed with CellQuest (Becton Dickinson) or FlowJo (Tree Star, Ashland, OR) programs.

Conjugate Assay.

Cultured NK cells were labeled with 2 μM 5-(and -6)-(((4-chloromethyl)benzoyl)amino)tetramethyl-rhodamine Orange (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA), and, if needed, C1498 target cells were labeled with 0.1 μM 5- (and 6-)carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (Molecular Probes) for 10 min at 37°C at 5–10 × 106 cells per ml. A total of 105 NK cells was mixed with target cells at a 1:1 ratio in a final volume of 200 μl of DMEM/5% FCS and centrifuged for 2 min at 50 × g at 4°C. After incubation at 37°C for various periods of time, conjugates were gently resuspended by pipetting, fixed by adding 500 μl of 1% paraformaldehyde in cold PBS, and analyzed on a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). For antibody blocking experiments, NK cells were preincubated with 10 μg/ml mAb for 20 min at 4°C. A mAb concentration of 10 μg/ml was maintained during the assay.

Confocal Microscopy.

NK cells and target cells were mixed at a 1:1, 1:2, or 2:1 ratio, centrifuged, and incubated for 6–8 min at 37°C. After gentle resuspension, the conjugates were allowed to adhere for 1–2 min on poly(l-lysine)- or poly(d-lysine)-coated microscopic slides and then fixed at room temperature for 10 min with 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS or cold acetone. Anti-Ly49A staining was done by using mAb JR9-318 followed by Alexa 568-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (Molecular Probes). Series of 7–16 confocal images per conjugate were acquired along the z-axis with a Leica SP-2 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) by using a Plan Apo oil ×63/1.4 objective. Serial acquisition of YFP (green detector, 520–569 nm) and Ly49A signal (red detector, 599–733 nm) were done to avoid cross-talk between YFP and Alexa 568 fluorochromes. The analysis was performed by using the Image J software (National Institutes of Health; http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) on maximum intensity projections of three to seven images covering the interaction interface. Fold enrichment was determined as follows: (integrated fluorescence density at the interaction gate/area of interaction gate)/(integrated fluorescence density at control gates/area of control gates). Single cells (not involved in interactions with other cells) were used for reference quantifications: integrated fluorescence density in an arbitrarily chosen region (at the north pole) was compared with that of three control regions.

Statistical Analysis.

All P values were determined by using a Wilcoxon rank test. Data sets were considered significantly different when P < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Garin, M. Allegrini, and J. Artacho (Microscopy and Imaging Facility of the Swiss Cancer Research Institute; Epalinges, Switzerland) for help with confocal microscopy; P. Guillaume for the preparation of multimers; F. Lévy for the anti-MHC-I Ab; and S. Valitutti for helpful suggestions. This research was supported in part by a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation (to W.H.).

Abbreviations

- Dd

H-2Dd MHC class I molecule

- EYFP

enhanced yellow fluorescent protein

- KIR

killer Ig-like receptor

- LFA-1

leukocyte function-associated antigen-1

- MHC-I

MHC class I molecule

- NK

natural killer

- PE

phycoerythrin

- Tg

transgene/transgenic.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS direct submission.

References

- 1.Lanier LL. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:225–274. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karlhofer FM, Ribaudo RK, Yokoyama WM. Nature. 1992;358:66–70. doi: 10.1038/358066a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanke T, Takizawa H, McMahon CW, Busch DH, Pamer EG, Miller JD, Altman JD, Liu Y, Cado D, Lemonnier FA, et al. Immunity. 1999;11:67–77. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doucey MA, Scarpellino L, Zimmer J, Guillaume P, Luescher IF, Bron C, Held W. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:328–336. doi: 10.1038/ni1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tormo J, Natarajan K, Margulies DH, Mariuzza RA. Nature. 1999;402:623–631. doi: 10.1038/45170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsumoto N, Mitsuki M, Tajima K, Yokoyama WM, Yamamoto K. J Exp Med. 2001;193:147–157. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.2.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang J, Whitman MC, Natarajan K, Tormo J, Mariuzza RA, Margulies DH. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:1433–1442. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110316200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dam J, Baber J, Grishaev A, Malchiodi EL, Schuck P, Bax A, Mariuzza RA. J Mol Biol. 2006;362:102–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dam J, Guan R, Natarajan K, Dimasi N, Chlewicki LK, Kranz DM, Schuck P, Margulies DH, Mariuzza RA. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1213–1222. doi: 10.1038/ni1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Razi N, Varki A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7469–7474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins BE, Blixt O, DeSieno AR, Bovin N, Marth JD, Paulson JC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6104–6109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400851101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsumoto G, Nghiem MP, Nozaki N, Schmits R, Penninger JM. J Immunol. 1998;160:5781–5789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barber DF, Faure M, Long EO. J Immunol. 2004;173:3653–3659. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eriksson M, Leitz G, Fallman E, Axner O, Ryan JC, Nakamura MC, Sentman CL. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1005–1012. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.7.1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burshtyn DN, Shin J, Stebbins C, Long EO. Curr Biol. 2000;10:777–780. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00568-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vyas YM, Mehta KM, Morgan M, Maniar H, Butros L, Jung S, Burkhardt JK, Dupont B. J Immunol. 2001;167:4358–4367. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCann FE, Suhling K, Carlin LM, Eleme K, Taner SB, Yanagi K, Vanherberghen B, French PM, Davis DM. Immunol Rev. 2002;189:179–192. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2002.18915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vyas YM, Maniar H, Dupont B. Immunol Rev. 2002;189:161–178. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2002.18914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis DM, Chiu I, Fassett M, Cohen GB, Mandelboim O, Strominger JL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:15062–15067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fassett MS, Davis DM, Valter MM, Cohen GB, Strominger JL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:14547–14552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211563598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faure M, Barber DF, Takahashi SM, Jin T, Long EO. J Immunol. 2003;170:6107–6114. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.6107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eriksson M, Ryan JC, Nakamura MC, Sentman CL. Immunology. 1999;97:341–347. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00800.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burshtyn D, Scharenberg A, Wagtmann N, Rajagopalan S, Peruzzi M, Kinet J-P, Long EO. Immunity. 1996;4:77–85. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80300-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lou Z, Jevremovic D, Billadeau DD, Leibson PJ. J Exp Med. 2000;191:347–354. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.2.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vyas YM, Maniar H, Lyddane CE, Sadelain M, Dupont B. J Immunol. 2004;173:1571–1578. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaufman DS, Schoon RA, Robertson MJ, Leibson PJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6484–6488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Daniels BF, Nakamura MC, Rosen SD, Yokoyama WM, Seaman WE. Immunity. 1994;1:785–792. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(94)80020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brennan J, Mahon G, Mager DL, Jefferies WA, Takei F. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1553–1559. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zimmer J, Ioannidis V, Held W. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1531–1539. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.10.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collins BE, Blixt O, Han S, Duong B, Li H, Nathan JK, Bovin N, Paulson JC. J Immunol. 2006;177:2994–3003. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.2994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Held W, Cado D, Raulet DH. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2037–2041. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ioannidis V, Zimmer J, Beermann F, Held W. J Immunol. 2001;167:6256–6262. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altman JD, Moss PAH, Goulder PJR, Barouch DH, McHeyzer-Williams MG, Bell JI, McMichel AJ, Davis MM. Science. 1996;274:94–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]