Abstract

MDR1 (multidrug resistance 1)/P-glycoprotein is an ATP-driven transporter which excretes a wide variety of structurally unrelated hydrophobic compounds from cells. It is suggested that drugs bind to MDR1 directly from the lipid bilayer and that cholesterol in the bilayer also interacts with MDR1. However, the effects of cholesterol on drug–MDR1 interactions are still unclear. To examine these effects, human MDR1 was expressed in insect cells and purified. The purified MDR1 protein was reconstituted in proteoliposomes containing various concentrations of cholesterol and enzymatic parameters of drug-stimulated ATPase were compared. Cholesterol directly binds to purified MDR1 in a detergent soluble form and the effects of cholesterol on drug-stimulated ATPase activity differ from one drug to another. The effects of cholesterol on Km values of drug-stimulated ATPase activity were strongly correlated with the molecular mass of that drug. Cholesterol increases the binding affinity of small drugs (molecular mass <500 Da), but does not affect that of drugs with a molecular mass of between 800 and 900 Da, and suppresses that of valinomycin (molecular mass >1000 Da). Vmax values for rhodamine B and paclitaxel are also increased by cholesterol, suggesting that cholesterol affects turnover as well as drug binding. Paclitaxel-stimulated ATPase activity of MDR1 is enhanced in the presence of stigmasterol, sitosterol and campesterol, as well as cholesterol, but not ergosterol. These results suggest that the drug-binding site of MDR1 may best fit drugs with a molecular mass of between 800 and 900 Da, and that cholesterol may support the recognition of smaller drugs by adjusting the drug-binding site and play an important role in the function of MDR1.

Keywords: cholesterol, drug-binding pocket, multidrug resistance, substrate recognition

Abbreviations: ABC, ATP-binding cassette; c.m.c., critical micellar concentration; DDM, N-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside; DTT, dithiothreitol; HEK, human embryonic kidney; KcsA, bacterial K+ channel protein; MβCD, methyl-β-cyclodextrin; MDR1, multidrug resistance 1; Ni-NTA, Ni2+-nitrilotriacetate; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PS, phosphatidylserine

INTRODUCTION

MDR1 (multidrug resistance 1; ABCB1) is a plasma membrane-located glycoprotein that confers multidrug resistance on cancer cells by actively excreting structurally diverse chemotherapeutic compounds from cells [1–4]. MDR1 is clinically important because it not only confers multidrug resistance but also affects the pharmacokinetics of various drugs [5–7].

MDR1 is a 1280-amino acid protein with two symmetrical halves connected by a short linker region [8]. Each half consists of six putative transmembrane helices followed by a nucleotide binding fold, in which ATP is hydrolysed to energize the transport. The hydrolysis is thought to be directly linked to drug transport and both nucleotide binding folds should be catalytically active [9,10], although the exact number of ATP molecules hydrolysed for a single transport is still unknown [11,12].

As structural information on MDR1 is limited, it is not known how MDR1 recognizes and transports such structurally diverse compounds. However, biochemical studies have revealed that MDR1 possesses multiple drug-binding sites [13–15] and these sites are located in the middle of the lipid bilayer [16]. Shapiro et al. [14] demonstrated that MDR1 possesses at least three positively co-operating drug-binding sites, an H site selective for Hoechst 33342 and colchicine, an R site selective for rhodamine 123 and anthracyclines, and another site at which progesterone binds. Drug-binding to one site stimulates transport by the other. Moreover, rhodamine 123 and progesterone in combination stimulate the transport of Hoechst 33342 in an additive manner. Martin et al. [13] also assigned four drug-binding sites, three of which were classified as sites for transport and one for regulation of the transport.

Recently, many ABC (ATP-binding cassette) proteins have been reported to function in lipid homoeostasis. For example, ABCG5 and ABCG8 mediate the efflux of cholesterol and sitosterol from the intestine and hepatocytes into the intestinal lumen and bile duct [17]. ABCA1 mediates the efflux of cholesterol and phospholipids to form high density lipoprotein [18–20]. ABCB4 (MDR2), being highly homologous with MDR1, functions in the secretion of PC (phosphatidylcholine) into bile ducts from hepatocytes [21]. Therefore it is conceivable that MDR1 also interacts with membrane lipids. Indeed, it has been reported that cholesterol stimulates basal (i.e. without any drugs) ATPase activity [22,23], and that cholesterol is recognized and transported as an endogenous substrate of MDR1 [24]. It was also shown that depletion of cholesterol reduced the transport activity of MDR1, resulting in the intracellular accumulation of drugs in cells [23,25,26].

In the present study, we analysed the ATPase activity of MDR1 using purified human MDR1 reconstituted in liposomes containing 0–20% (w/w) cholesterol. Cholesterol increased the basal ATPase activity and affected the drug-stimulated ATPase activity of MDR1. The effects differ from one drug to another and can be classified into five types. [3H]Cholesterol was co-eluted with MDR1 in a gel-filtration assay. These results suggest that cholesterol directly binds to MDR1 and modulates substrate recognition by MDR1.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

Sf9 cells were obtained from Pharmingen. Lipids and ATP were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich. Medium, pluronic F-68 and gentamycin were obtained from Invitrogen. DDM (N-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside) was purchased from Anatrace. Ni-NTA (Ni2+-nitrilotriacetate) agarose was from Qiagen. [1α,2α(n)-3H]Cholesterol was from Amersham Biosciences. Other compounds were from Sigma–Aldrich or Wako.

Protein expression and purification

A sequence encoding a thrombin-cleavage site, ten histidine codons and a termination codon was inserted at the 3′ end of human MDR1 cDNA [27]. The modified MDR1 was expressed in insect cells with the use of a recombinant baculovirus and purified by Ni-NTA chromatography as described in [28] with some modifications. The microsomal pellet was treated with 0.5 M NaCl before membrane proteins were solubilized with 0.8% (w/w) DDM to remove the peripherally anchored proteins as described else-where in detail (Kodan, A., Shibata, H., Matsumoto, T., Matsuo, M., Ueda, K. and Kato, K., unpublished work).

The N-terminus decahistidine-tagged KcsA expression vector was kindly provided by Dr Ichio Shimada (Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Tokyo, Tokyo). His-tagged KcsA (bacterial K+ channel protein) was expressed and purified according to a previously published report with minor modifications [29]. The Escherichia coli strain C41 was transformed with the expression plasmid and cultured in Luria–Bertani medium supplemented with 50 mg/l kanamycin. The protein expression was induced by the addition of 1 mM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside at D600=0.6. Cells were harvested at 6 h post-induction and disrupted by sonication. The membrane proteins were solubilized by PBS containing 1% DDM at room temperature (25 °C) and purified with Ni-NTA agarose. In the final step of purification, the detergent was replaced with 0.1% deoxycholate.

Reconstitution into proteoliposomes

PC, PE (phosphatidylethanolamine), PS (phosphatidylserine) and cholesterol were dissolved in chloroform mixed in a proper ratio, and dried under high vacuum for over 2.5 h to remove the chloroform. The lipid film was resuspended at 10 mg/ml in 40 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.4) and 0.1 mM EGTA by sonication in a bath sonicator (Bioruptor CD-200 TM, Cosmo Bio) until the suspension clarified. After sonication, lipids were kept on ice for 24 h and subjected to two cycles of freeze–thawing. Finally, lipids were sonicated again (5 cycles, 30 s each, 2 min rests on ice between cycles). Lipid stocks were used within a week. For reconstitution, purified protein and lipid stocks were mixed at a protein/lipid ratio of 1:10 and incubated at 23 °C for 20 min, and sonicated for 15 s in a bath sonicator as reported previously [28].

MDR1 ATPase activity

The ATPase reaction was performed following methods reported previously [28] with minor modifications. Reconstituted protein (30–100 ng) was reacted in 20 μl of 40 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 0.1 mM EGTA, 1 mM NaATP, 1 mM MgCl2 and various concentrations of drugs at 37 °C for 30 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 10 μl of 3% SDS and 10 mM vanadate.

Enzymatic parameter

The experimental data were computer-fitted to the Michaelis–Menten equation, v=VDmax[S]/(Km+[S]), where v is drug-stimulated ATPase activity and [S] is the drug concentration. Fitting was carried out using the least-squares method (KaleidaGraph) and values for the VDmax and Km were extracted. Vmax values shown in Tables 1 and 2 include the drug-stimulated and sterol-stimulated ATPase activity. For VDmax, v is the ATPase activity stimulated by drug alone. For Vmax, v is the ATPase activity stimulated by cholesterol and drug.

Table 1. Km and Vmax values of drug-stimulated ATPase activity of MDR1 reconstituted in liposomes containing various concentrations of cholesterol.

Purified MDR1 was reconstituted in liposomes of various concentrations of cholesterol and ATPase activity was examined in the presence of the indicated drugs. Data were fit to a Michaelis–Menten equation after subtracting the basal activity (0% cholesterol without drugs), and Km or Vmax values (which include the stimulation by cholesterol) were extracted. Values are means±S.D. (n=3). Relative values (percentage change) with respect to control (0% cholesterol) are shown in parentheses.

| Drug | Molecular mass (Da) | Cholesterol (%) | Km (μM) | Vmax (nmol/min/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhodamine 123 | 345 | 0 | 21±2 | 874±28 |

| 5 | 16±2 (76) | 886±45 (101) | ||

| 10 | 13±1 (62)* | 983±24 (112)** | ||

| 20 | 10±1 (48)* | 757±15 (87)** | ||

| Dexamethasone | 392 | 0 | 826±139 | 690±67 |

| 5 | 527±88 (64)* | 586±68 (85)** | ||

| 10 | 423±62 (51)* | 620±39 (90)** | ||

| 20 | 394±3 (48)* | 723±23 (105) | ||

| Verapamil | 455 | 0 | 4.1±0.4 | 690±24 |

| 5 | 3.8±0.3 (93) | 637±9 (92)* | ||

| 10 | 2.7±0.0 (66)* | 719±4 (104) | ||

| 20 | 2.2±0.2 (54)* | 646±12 (94) | ||

| Nicardipine | 480 | 0 | 2.6±0.2 | 568±29 |

| 5 | 1.5±0.1 (58)** | 596±15 (105) | ||

| 10 | 1.6±0.3 (62)* | 634±24 (112)* | ||

| 20 | 1.0±0.2 (38)** | 536±16 (94) | ||

| Digoxin | 781 | 0 | 181±11 | 578±20 |

| 5 | 120±8 (66)** | 598±2 (103) | ||

| 10 | 111±20 (61)** | 633±26 (110)* | ||

| 20 | 76±7 (42)** | 576±26 (100) | ||

| Rhodamine B | 444 | 0 | 14±3 | 233±21 |

| 5 | 9±3 (64)* | 291±23 (125)* | ||

| 10 | 11±1 (79) | 305±23 (131)* | ||

| 20 | 7±1 (50)** | 314±3 (135)* | ||

| Vinblastine | 811 | 0 | 1.7±0.3 | 347±5 |

| 5 | 1.3±0.1 (76) | 368±7 (106)* | ||

| 10 | 1.2±0.1 (71) | 304±2 (88)** | ||

| 20 | 1.6±0.3 (94) | 297±2 (86)** | ||

| Vincristine | 825 | 0 | 3.7±0.6 | 199±20 |

| 5 | 2.7±0.4 (73) | 307±11 (154)** | ||

| 10 | 2.8±0.4 (76) | 215±6 (108) | ||

| 20 | 3.9±0.2 (105) | 196±6 (98) | ||

| Paclitaxel | 854 | 0 | 1.4±0.2 | 160±10 |

| 5 | 1.3±0.1 (93) | 235±3 (147)** | ||

| 10 | 1.4±0.1 (100) | 363±7 (227)** | ||

| 20 | 1.6±0.2 (114) | 411±8 (257)** | ||

| Valinomycin | 1111 | 0 | 2.5±0.2 | 400±2 |

| 5 | 2.2±0.1 (88) | 408±13 (102) | ||

| 10 | 2.6±0.2 (104) | 508±7 (127)** | ||

| 20 | 3.5±0.1 (140)** | 418±9 (105) |

*P<0.05 with respect to control (0% cholesterol).

**P<0.01 with respect to control (0% cholesterol).

Table 2. Km and Vmax values of paclitaxel-stimulated ATPase activity of MDR1 reconstituted in liposomes containing various sterols (20%, w/w).

| Km (μM) | Vmax (nmol/min/mg) | |

|---|---|---|

| −sterol | 1.4±0.2 | 160±10 |

| Cholesterol | 1.6±0.2 | 411±8* |

| Stigmasterol | 1.4±0.1 | 379±11* |

| Sitosterol | 1.1±0.2 | 325±13* |

| Campesterol | 1.0±0.1* | 300±4* |

| Ergosterol | 0.9±0.1* | 177±3 |

*P<0.01 with respect to control (−sterol).

In vitro cholesterol-binding assays

In vitro cholesterol-binding assays were carried out using size-exclusion chromatography and Ni-NTA pull-down assays were conducted as previously reported [30,31] with some modifications. Cholesterol–MβCD (methyl-β-cyclodextrin) complexes were prepared by mixing 1 volume of ethanol-dissolved [3H]cholesterol with 4.5 volumes of MβCD at a molar ratio of 1:50 and incubating the mixture for more than 30 min at room temperature. For gel-filtration assays, purified MDR1 (6 μg) in a 0.1% deoxycholate solution was mixed with cholesterol–MβCD complexes in a final volume of 10 μl of separation buffer [40 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.4), 0.1% deoxycholate and 2 mM DTT (dithiothrietol)]. Samples were incubated at 37 °C for 2 min and loaded on a column of Sephadex G100 (1 ml) pre-equilibrated in 40 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.4) and 0.1% deoxycholate. Fractions (10×100 μl) were collected and analysed for radioactivity with a liquid-scintillation counter. MDR1 protein was visualized by silver staining after SDS/PAGE. For Ni-NTA pull-down assays, 6 μg of purified protein was mixed with cholesterol–MβCD complexes in a final volume of 10 μl of reaction buffer [40 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.4), 0.1% deoxycholate and 150 mM NaCl]. Samples were incubated at 37 °C for 2 min and 20 μl of Ni-NTA agarose was added. Proteins were eluted from Ni-NTA agarose by 500 mM imidazole after washing and analysed for radioactivity with a liquid-scintillation counter.

Expression of MDR1 in FreeStyle HEK (human embryonic kidney)-293F cells and analysis of ATPase activity

FreeStyle HEK-293F cells were cultured in Free Style 293 expression medium according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were transfected with the human MDR1 expression vector pCAGGSP/MDR1 (1 μg/ml) [10] at a cell density of 1.0×106/ml and harvested 48 h after transfection. The membrane fraction (15 μg of protein) was incubated in 20 μl of PBS containing protease inhibitors, 1 mM EDTA and 10 mM MβCD for 90 min at 25 °C. The supernatant was removed after centrifugation (16000 g for 5 min at room temperature), and the pellet was washed with PBS and subjected to ATPase analysis. To measure ATPase activity, the reaction was performed in 40 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5) containing 0.1 mM EGTA, 2 mM NaATP, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT and 1mM NaN3 at 37 °C for 30 min. ATPase activity was calculated by measuring inorganic phosphate as reported in [32].

RESULTS

ATPase activity of purified human MDR1

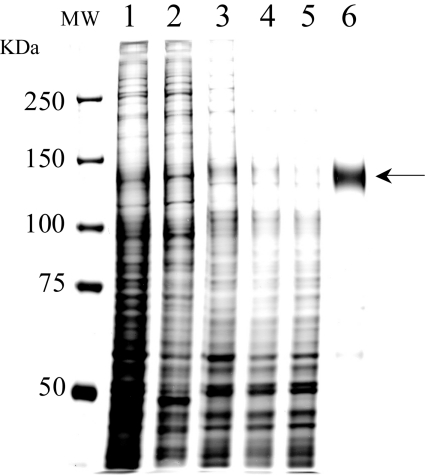

Human MDR1, fused with a histidine tag at the C-terminus, was expressed at high levels in insect cells with an MDR1 recombinant baculovirus, and purified as previously reported [28]. MDR1 was extracted with 0.8% DDM, and purified by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography. MDR1 was recovered from the resin with 300 mM imidazole with a purity of more than 95% as judged from silver staining (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Purification of human MDR1 expressed in insect cells.

Aliquots from each step of purification were subjected to SDS/PAGE on an 8% polyacrylamide gel and visualized by silver staining. Lane 1, microsomal proteins from Sf9 cells expressing human MDR1; lane 2, peripheral proteins removed from microsomes by treatment with 0.5 M NaCl; lane 3, integral membrane proteins recovered after 0.5 M NaCl treatment; lane 4, microsomal proteins solubilized with 0.8% DDM; lane 5, proteins not bound to Ni-NTA resin; lane 6, eluate from Ni-NTA resin with 300 mM imidazole. Lanes 1–5, 2 μg of protein was loaded; lane 6, 0.3 μg of protein was loaded. MDR1 is indicated by the arrow.

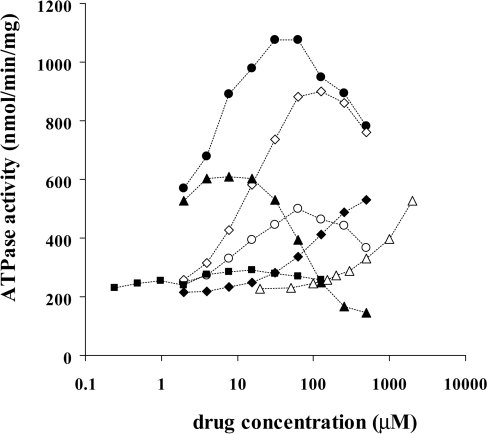

Purified MDR1 was reconstituted in liposomes (PC/PE/PS=4:4:2), and ATPase activity was measured by HPLC with a titanium dioxide column [28]. Various compounds increased ATPase activity (Figure 2). A typical concentration-dependence with a bell-shaped curve [33,34] was obtained with verapamil and rhodamine 123; the ATPase activity increased as the concentration rose and peaked at about 30 μM and 125 μM respectively, whereas it was rather suppressed at higher concentrations. Vinblastine stimulated MDR1 ATPase activity at 10 μM or less but showed strong inhibitory effects at higher concentrations and suppressed ATPase activity below the basal level (approx. 200 nmol/min/mg) at 200 μM or more. With increasing concentration of colchicine there was an increase in ATPase, but maximal activity was not obtained even at 2 mM. Without the reconstitution in liposomes, ATPase activity was not stimulated by the addition of substrate drugs (results not shown), suggesting that the lipid environment is quite important for the function of MDR1 as reported previously [22].

Figure 2. The effect of various drugs on the ATPase activity of purified MDR1.

Purified MDR1 was reconstituted in PC/PE/PS (4:4:2) liposomes and ATPase activity was measured as described in the Experimental section. ●, Verapamil; ○, rhodamine B; ◆, digoxin; ◇, rhodamine 123; ▲, vinblastine; △, colchicine; ■, paclitaxel.

Effects of cholesterol on MDR1 ATPase activity

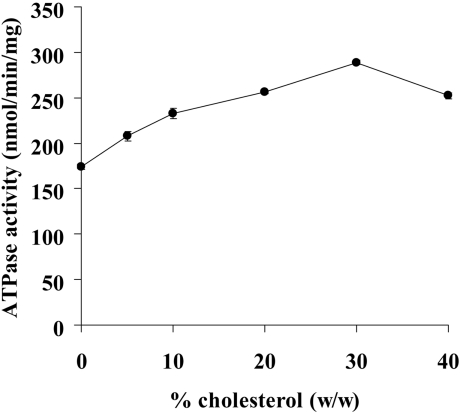

It has been suggested that the basal ATPase activity of human MDR1 in native membrane vesicles is highly dependent on the presence of cholesterol [23,24], and also that the basal ATPase activity of partially purified hamster MDR1, reconstituted in PC/PE (9:1) liposomes, is dependent on the presence of cholesterol [22]. We examined whether cholesterol affects the ATPase activity of purified human MDR1 by reconstituting the protein in liposomes (PC/PE/PS=4:4:2) containing various concentrations of cholesterol (Figure 3). The ATPase activity increased as the concentration of cholesterol increased and peaked at 30% (w/w) cholesterol. In the presence of 30% cholesterol, the ATPase activity of MDR1 was 1.7-fold greater than ATPase activity in the absence of cholesterol. This suggests that cholesterol directly interacted with MDR1 at drug-binding sites. Alternatively, cholesterol may have affected the lipid environment, fluidity for example, and indirectly increased the turnover of basal ATP hydrolysis.

Figure 3. Effects of cholesterol on the basal ATPase activity.

Purified MDR1 was reconstituted in PC/PE/PS (4:4:2) liposomes containing 0, 5, 10, 20, 30 or 40% (w/w) cholesterol. Data are presented as means±S.D. (n=3).

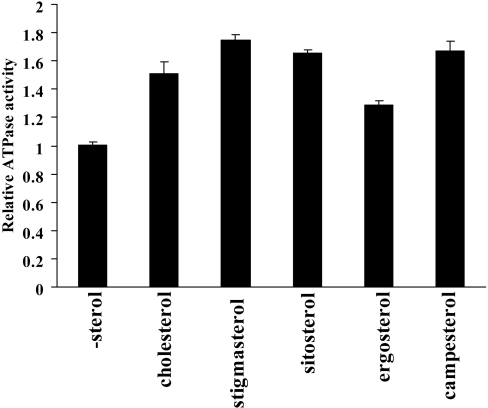

Effects of various sterols on basal activity

To consider the possibility of an indirect effect of cholesterol on MDR1, the specificity of sterol species was examined (Figure 4). Stigmasterol, sitosterol and campesterol stimulated the MDR1 ATPase activity as efficiently as cholesterol. Ergosterol was less effective than other sterols. The specific effect of sterols on MDR1 ATPase activity may support the direct interaction of sterols with MDR1.

Figure 4. Effects of sterols on the basal ATPase activity.

Purified MDR1 was reconstituted in liposomes containing 20% (w/w) cholesterol, stigmasterol, β-sitosterol, ergosterol or campesterol. Relative ATPase activity is presented with respect to that in the absence of sterol (-sterol)±S.D. (n=3).

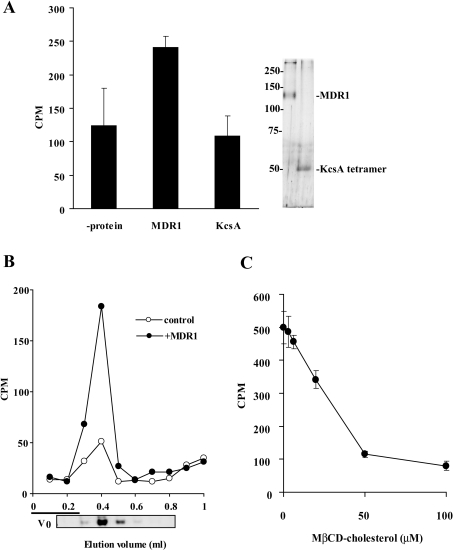

Binding of [3H]cholesterol to detergent soluble MDR1

The direct binding of cholesterol to purified MDR1 was confirmed by two methods, a pull-down assay and size-exclusion chromatography. We found that a significant amount of cholesterol bound to micelles of DDM and eluted in earlier fractions (fractions 3–5) in both the absence and presence of MDR1. Thus, for the in vitro cholesterol binding assay, the detergent was replaced with 0.1% deoxycholate, which has a much higher c.m.c (critical micellar concentration) value and forms smaller micelles compared with those of DDM. MDR1 purified in 0.1% deoxycholate showed as much ATPase activity as that purified in DDM when reconstituted in proteoliposomes. Moreover, when MDR1 purified in 0.1% deoxycholate was reconstituted in liposomes containing 20% cholesterol, the Km value for verapamil was decreased from 4.7±0.4 μM to 1.9±0.2 μM as discussed later (Table 1). These results suggest that MDR1 purified in deoxycholate is catalytically active and has similar features to MDR1 purified in DDM.

The Ni-NTA pull-down assay revealed that [3H]cholesterol was co-precipitated with MDR1, but not with KcsA, whereas similar amounts of MDR1 and KcsA were precipitated (Figure 5A). To investigate further the binding of cholesterol to purified MDR1, size-exclusion chromatography was used. Soluble MDR1 was mixed with the cholesterol–MβCD complex and loaded on to the column. When the cholesterol–MβCD complex was mixed with MDR1, cholesterol was co-eluted with MDR1 (Figure 5B). In contrast, most cholesterol was retained in the column and was not eluted from Sephadex G100 resin when the cholesterol–MβCD complex was applied to the column without MDR1, probably due to non-specific binding to the resin. The amount of cholesterol bound to MDR1 was correlated with the [3H]cholesterol concentration and the amount of MDR1 (results not shown). Furthermore, the binding of [3H]cholesterol to MDR1 was competitively inhibited by the unlabelled cholesterol–MβCD complex (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. Binding of cholesterol to purified MDR1.

(A) Purified proteins (6 μg) were mixed with 3 μM of the [3H]cholesterol–MβCD complex at 37 °C for 2 min and Ni-NTA agarose was added. Proteins were eluted by 500 mM imidazole and analysed for radioactivity with a liquid-scintillation counter. Eluted protein was subjected to SDS/PAGE and visualized by silver-staining (right-hand panel). (B) Purified MDR1 (6 μg) was mixed with 3 μM [3H]cholesterol–MβCD complex at 37 °C for 2 min then loaded on a column of Sephadex G100 (1 ml) and each fraction (10×100 μl) was analysed for radioactivity with a liquid-scintillation counter. MDR1 protein was visualized by silver staining after SDS/PAGE. The column void volume is shown as V0. (C) Competitive inhibition of [3H]cholesterol with unlabelled cholesterol. Purified MDR1 was mixed with 3 μM [3H]cholesterol–MβCD complex and unlabelled cholesterol–MβCD complex. Fractions 3–6 were mixed and the amount of eluted [3H]cholesterol was analysed.

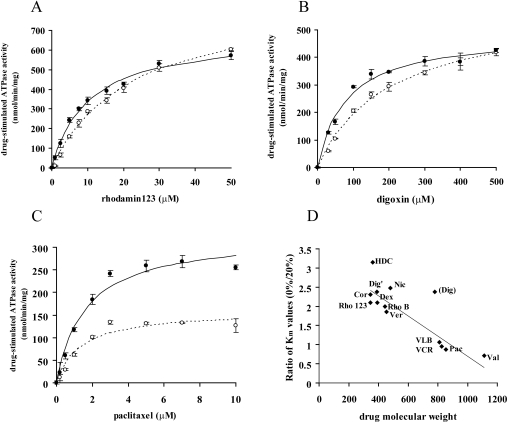

Effect of cholesterol on the drug-stimulated ATPase activity of MDR1

MDR1 has been suggested to possess multiple drug-binding sites, and a drug binding to one site allosterically modulates drugs binding to other sites [13–15]. Because the above results suggested that cholesterol interacts directly with MDR1, we expected cholesterol to affect the drug-stimulated ATPase activity of MDR1. We examined the drug-stimulated ATPase activity of MDR1 reconstituted either in liposomes (PC/PE/PS=4:4:2) or in liposomes containing 20% (w/w) cholesterol. In the cases of rhodamine 123 and digoxin, the presence of cholesterol had little affect on the Vmax of ATPase activity but significantly lowered the Km value from 21 to 10 μM (Figure 6A, Table 1) and from 181 to 76 μM (Figure 6B, Table 1) respectively.

Figure 6. The effect of cholesterol on drug-stimulated ATPase activity.

Purified MDR1 reconstituted in liposomes containing 0% (open symbols) or 20% (filled symbols) cholesterol was reacted in the presence of various concentrations of drugs. (A) Rhodamine 123, (B) digoxin, and (C) paclitaxel. Experiments were performed in triplicate and means±S.D. are shown. After subtraction of the basal (without drug) activity, data were fitted to the Michaelis–Menten equation and Km and VDmax values were extracted. Lines represent calculated best-fit curves. (D) Relationship between the ratio of Km values in the absence and presence of 20% (w/w) cholesterol and the molecular masses of drugs. The line represents the best fit linear regression (r2=0.8075; excluding the points for digoxin). Rho123, rhodamine 123; Cor, corticosterone; HDC, hydrocortisone; Dex, dexamethasone; Dig', aglycon form of digoxin; RhoB, rhodamine B; Ver, verapamil; Nic, nicardipine; Dig; digoxin; VLB, vinblastine; VCR, vincristine; Pac, paclitaxel; Val, valinomycin.

In contrast, the presence of cholesterol had little affect on the Km for paclitaxel, but increased the Vmax from 160 to 411 nmol/min/mg (Figure 6C, Table 1). These results suggested that cholesterol affected the drug-stimulated ATPase activity of MDR1 and effects of cholesterol differed from one drug to another: the presence of cholesterol increases the affinity of MDR1 for rhodamine 123 and digoxin, whereas it increases the paclitaxel-induced hydrolysis of ATP by MDR1. Km values for ATP were not affected by cholesterol in the absence or presence of paclitaxel (results not shown).

To further analyse effects of cholesterol on the drug-stimulated hydrolysis of ATP by MDR1, MDR1 was reconstituted in liposomes containing 0, 5, 10 or 20% (w/w) cholesterol and the enzymatic parameters of ATPase activity for ten drugs, rhodamine 123, verapamil, dexamethasone, digoxin, nicardipine, rhodamine B, paclitaxel, vinblastine, vincristine, and valinomycin, were examined (Table 1). The effects of cholesterol on Km and Vmax values of MDR1 ATPase activity differ from one drug to another as discussed later in the Discussion section.

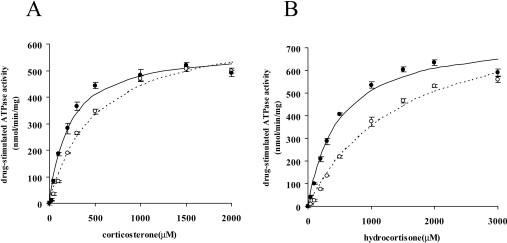

Effect of cholesterol on steroid-stimulated ATPase activity of MDR1

We initially presumed that cholesterol would compete with dexamethasone at the shared binding site and increase the Km value for dexamethasone. However, as shown in Table 1, cholesterol decreased the Km value for dexamethasone, indicating that the binding site for cholesterol is different from that for dexamethasone. To further examine the effect of cholesterol, we analysed effects on the ATPase activity of MDR1 stimulated by corticosterone and hydrocortisone (Figure 7). Km values for both corticosterone and hydrocortisone decreased from 485 μM to 210 μM and from 1498 μM to 475 μM respectively when MDR1 was reconstituted in liposomes containing 20% cholesterol.

Figure 7. Effects of cholesterol on corticosterone- and hydrocortisone-stimulated ATPase activity.

Purified MDR1 reconstituted in liposomes containing 0% (open symbols) or 20% (filled symbols) cholesterol was reacted in the presence of corticosterone (A) or hydrocortisone (B). Experiments were performed in triplicate and means±S.D. are shown. Lines represent calculated best-fit curves.

Effects of sterols on paclitaxel-stimulated ATPase activity of MDR1

Table 2 shows the effects of various sterols on the paclitaxel-stimulated ATPase activity of MDR1. Stigmasterol, sitosterol and campesterol as well as cholesterol increased the Vmax value significantly. Ergosterol increased the Vmax value slightly. On the other hand, all of these sterols decreased the Km value and increased the Vmax value of the rhodamine B-stimulated ATPase activity of MDR1 as efficiently as cholesterol (results not shown). These results also suggest that the action of sterols is drug specific.

Effect of cholesterol depletion on drug-stimulated ATPase activity of MDR1 in mammalian cells

It has been reported that the depletion of membrane cholesterol significantly reduces the MDR1-mediated transport activity [23,26]. To investigate the role of cholesterol in the MDR1 ATPase activity in mammalian cells, we expressed MDR1 in FreeStyle HEK-293F cells and analysed the effect of cholesterol depletion on the verapamil-stimulated ATPase activity. With the depletion of cholesterol with 10 mM MβCD, the Km value for verapamil shifted from 3.2±0.8 μM to 4.4±0.2 μM, although the Vmax value was not reduced. This result suggests that the amount of cholesterol also affects the Km value for drugs of MDR1 in native membranes, as observed in reconstituted liposomes.

DISCUSSION

The results obtained in the present study demonstrate that cholesterol in membranes interacts directly with MDR1 and affects not only the basal ATPase activity but also the drug-stimulated ATPase activity of MDR1. Cholesterol affects both drug-binding (Km) and turnover of ATP hydrolysis (Vmax) of the purified human MDR1 reconstituted in liposomes. The effects of cholesterol differ from one drug to another and can be classified into five types depending on changes of kinetic parameters (Table 1). Type I involves rhodamine 123, dexamethasone, verapamil, nicardipine and digoxin: the Km decreases in the presence of 20% cholesterol, but the Vmax is little affected. Type II involves rhodamine B: the Km decreases and the Vmax increases in the presence of cholesterol. Type III involves vinblastine and vincristine: neither the Km nor the Vmax is affected greatly. Type IV involves paclitaxel: the Km is not much affected and the Vmax increases in the presence of cholesterol. Type V involves valinomycin: the Km increases in the presence of cholesterol and the Vmax is little affected.

The effects of cholesterol on the Km were drug-specific. When the ratio of the Km of each drug in the absence and presence of 20% cholesterol was plotted against the molecular mass of that drug, a strong correlation was found between them (Figure 6D). At first glance, digoxin did not fit the correlation, but when the aglycon form of digoxin (molecular mass 390 Da) was plotted on the graph, it fitted well. The binding affinity of drugs with a small molecular mass, between 350 and 500 Da, increased in the presence of 20% cholesterol, and these drugs (rhodamine 123, dexamethasone, verapamil, nicardipine, digoxin, corticosterone, hydrocortisone and rhodamine B) are categorized into type I and type II (Table 1, Figure 6D). The binding affinity of drugs with a molecular mass of between 800 and 900 Da is not affected much by cholesterol, and these drugs (vinblastine, vincristine and paclitaxel) are categorized into type III and type IV. The binding affinity of valinomycin (type V), whose molecular mass is over 1000 Da, decreased in the presence of 20% cholesterol.

The effects of cholesterol might possibly arise indirectly, secondary to changes in the properties of the proteoliposomes such as permeability of the drugs or fluidity of the lipid bilayer. However, there are no correlations between hydrophobicity (logP values) of drugs and the effects of cholesterol on either the Km or Vmax values. Cholesterol exerted various effects on the Km in a drug-specific manner as described above, suggesting that those effects were caused by a direct interaction between MDR1 and cholesterol. The effects of cholesterol on the Vmax values were also drug-specific. The Vmax values for rhodamine B and paclitaxel are significantly increased in the presence of 20% cholesterol, whereas those for other drugs are not (Table 1). Moreover, the effects on Vmax values of paclitaxel-stimulated ATPase activity are sterol-specific (Table 2). If the effects are thoroughly indirect, effects of cholesterol on drug-stimulated ATPase activity are expected to be observed for all the drugs. These results suggest that cholesterol affects the function of MDR1 by interacting with MDR1 directly, at least in part.

Modok et al. [35] showed that cholesterol alone does not alter the binding affinity for both nicardipine (molecular mass 480 Da) and XR9576 (molecular mass 647 Da). While these authors purified these proteins from drug-resistant Chinese-hamster ovary cells, in the present study we expressed and purified MDR1 in insect cells whose cholesterol content is quite low compared with that of mammalian cells [36]. This might affect the amount of cholesterol retained by the purified protein, which may cause the difference in the effects of exogenously added cholesterol.

The strong correlation between the effect of cholesterol on the Km for drugs and their molecular masses suggests that the primary effect of cholesterol could be on the drug-binding site. MDR1 has been suggested to possess several allosterically coupled drug-binding sites [13,14,37,38] and to bind more than one drug molecule at the same time [39,40]. Cholesterol may bind directly to or allosterically affect the drug-binding site to adjust its size for the drug. Because the binding affinity of drugs with a molecular mass of between 800 and 900 Da (vinblastine, vincristine and paclitaxel) is not affected by the presence of cholesterol, the drug-binding site of MDR1 may best fit drugs with these sizes. When small drugs, with a molecular mass of 350–500 Da, bind to MDR1, cholesterol (molecular mass 386.7 Da) may fill the empty space or allosterically tighten the drug-binding site and help is the recognition of smaller drugs.

We have previously demonstrated that the bulkiness of side chains at the position of His61 and its neighbouring amino acid residues in the first transmembrane helix is important for substrate specificity [41,42]. For example, the replacement of His61 by amino acids with bulkier side chains increased resistance to small drugs such as colchicine and VP16, while it lowered resistance to a large drug, vinblastine. Recently, it was also suggested that the first transmembrane helix forms part of the drug-binding pocket by cross-linking experiments using a thiol-reactive analogue of verapamil [43]. These observations also suggest that the size of the drug-binding pocket is important for recognizing drugs.

The most puzzling feature of MDR1 is its recognition of drugs with various structures and molecular masses, from 300 Da to well over 1000 Da. To function as an efflux pump for various lipophilic and toxic xenobiotics, it is necessary for MDR1 to recognize them as they pass through the lipid bilayer. Since substrate transport and ATP hydrolysis are tightly coupled, we have previously used purified human MDR1, reconstituted in liposomes, and measured the amounts of ADP released after the hydrolysis by HPLC with a titanium dioxide column [28]. Under our experimental conditions, the amount of detergent remaining in the ATPase reaction is less than 0.003%. This concentration is below the c.m.c. values of DDM (0.0087%), suggesting that reconstituted protein is embedded in the lipid bilayer. Moreover, the similar Km values for verapamil in the native membrane (FreeStyle HEK-293F) and reconstituted proteoliposome suggest that the purified MDR1 is under native conditions as embedded in the plasma membrane. Inhibitors for other membrane-bound ATPases such as sodium azide and ouabain, which are necessary when membrane-bound or partially purified MDR1 is used in experiments [44,45], were not needed in the present study. These experimental conditions allowed us to examine the effect of cholesterol in the lipid bilayer on the MDR1 ATPase activity in detail. Because cholesterol is a major [about 20% (w/w) of lipids] and important constituent of the plasma membrane [46], liposomes containing cholesterol would provide more favourable conditions for MDR1. The highly sensitive ATPase assay established in the present study will not only facilitate our understanding of the drug-recognition mechanism of MDR1 but will also be useful for screening drugs interacting with MDR1.

In summary, we have analysed the ATPase activity and cholesterol-binding of MDR1 using purified human MDR1. The results suggest that cholesterol binds directly to MDR1 and modulates substrate-recognition by MDR1. The binding affinity of drugs with a small molecular mass increased in the presence of cholesterol. Cholesterol may fill the empty space or allosterically tighten the drug-binding site and aid the recognition of smaller drugs, and facilitate the ability of MDR1 to recognize compounds with various structures and molecular masses.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Tatsuya Kusudo for discussions. We also thank Dr Atsushi Kodan and Dr Vassilis Koronakis for advice on experimental procedures. This work was supported by a Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research and Creative Scientific Research 15GS0301 from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan, the Association for the Progress of New Chemistry, and BRAIN (the Bio-oriented Technology Research Advancement Institution).

References

- 1.Juliano R. L., Ling V. A surface glycoprotein modulating drug permeability in Chinese hamster ovary cell mutants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1976;455:152–162. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(76)90160-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ueda K., Cardarelli C., Gottesman M. M., Pastan I. Expression of a full-length cDNA for the human ‘MDR1’ gene confers resistance to colchicine, doxorubicin and vinblastine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1987;84:3004–3008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.9.3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gottesman M. M., Pastan I. Biochemistry of multidrug resistance mediated by the multidrug transporter. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1993;62:385–427. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.002125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gottesman M. M., Pastan I., Ambudkar S. V. P-glycoprotein and multidrug resistance. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1996;6:610–617. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(96)80091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sparreboom A., van Asperen J., Mayer U., Schinkel A. H., Smit J. W., Meijer D. K., Borst P., Nooijen W. J., Beijnen J. H., van Tellingen O. Limited oral bioavailability and active epithelial excretion of paclitaxel (Taxol) caused by P-glycoprotein in the intestine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:2031–2035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ambudkar S. V., Dey S., Hrycyna C. A., Ramachandra M., Pastan I., Gottesman M. M. Biochemical, cellular and pharmacological aspects of the multidrug transporter. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1999;39:361–398. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.39.1.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greiner B., Eichelbaum M., Fritz P., Kreichgauer H. P., von Richter O., Zundler J., Kroemer H. K. The role of intestinal P-glycoprotein in the interaction of digoxin and rifampin. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;104:147–153. doi: 10.1172/JCI6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen C. J., Chin J. E., Ueda K., Clark D. P., Pastan I., Gottesman M. M., Roninson I. B. Internal duplication and homology with bacterial transport proteins in the mdr1 (P-glycoprotein) gene from multidrug-resistant human cells. Cell. 1986;47:381–389. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90595-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urbatsch I. L., Sankaran B., Bhagat S., Senior A. E. Both P-glycoprotein nucleotide-binding sites are catalytically active. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:26956–26961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takada Y., Yamada K., Taguchi Y., Kino K., Matsuo M., Tucker S. J., Komano T., Amachi T., Ueda K. Non-equivalent cooperation between the two nucleotide-binding folds of P-glycoprotein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;14:131–136. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(98)00099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ambudkar S. V., Cardarelli C. O., Pashinsky I., Stein W. D. Relation between the turnover number for vinblastine transport and for vinblastine-stimulated ATP hydrolysis by human P-glycoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:21160–21166. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eytan G. D., Regev R., Assaraf Y. G. Functional reconstitution of P-glycoprotein reveals an apparent near stoichiometric drug transport to ATP hydrolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:3172–3178. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.3172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin C., Berridge G., Higgins C. F., Mistry P., Charlton P., Callaghan R. Communication between multiple drug binding sites on P-glycoprotein. Mol. Pharmacol. 2000;58:624–632. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.3.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shapiro A. B., Fox K., Lam P., Ling V. Stimulation of P-glycoprotein-mediated drug transport by prazosin and progesterone: evidence for a third drug-binding site. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999;259:841–850. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loo T. W., Bartlett M. C., Clarke D. M. Methanethiosulfonate derivatives of rhodamine and verapamil activate human P-glycoprotein at different sites. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:50136–50141. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310448200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loo T. W., Clarke D. M. Location of the rhodamine-binding site in the human multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:44332–44338. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208433200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu L., Hammer R. E., Li-Hawkins J., Von Bergmann K., Lutjohann D., Cohen J. C., Hobbs H. H. Disruption of Abcg5 and Abcg8 in mice reveals their crucial role in biliary cholesterol secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:16237–16242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252582399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanaka A. R., Abe-Dohmae S., Ohnishi T., Aoki R., Morinaga G., Okuhira K., Ikeda Y., Kano F., Matsuo M., Kioka N., et al. Effects of mutations of ABCA1 in the first extracellular domain on subcellular trafficking and ATP binding/hydrolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:8815–8819. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206885200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee J. Y., Parks J. S. ATP-binding cassette transporter AI and its role in HDL formation. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2005;16:19–25. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200502000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takahashi K., Kimura Y., Kioka N., Matsuo M., Ueda K. Purification and ATPase activity of human ABCA1. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:10760–10768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513783200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Helvoort A., Smith A. J., Sprong H., Fritzsche I., Schinkel A. H., Borst P., van Meer G. MDR1 P-glycoprotein is a lipid translocase of broad specificity, while MDR3 P-glycoprotein specifically translocates phosphatidylcholine. Cell. 1996;87:507–517. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81370-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rothnie A., Theron D., Soceneantu L., Martin C., Traikia M., Berridge G., Higgins C. F., Devaux P. F., Callaghan R. The importance of cholesterol in maintenance of P-glycoprotein activity and its membrane perturbing influence. Eur. Biophys. J. 2001;30:430–442. doi: 10.1007/s002490100156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gayet L., Dayan G., Barakat S., Labialle S., Michaud M., Cogne S., Mazane A., Coleman A. W., Rigal D., Baggetto L. G. Control of P-glycoprotein activity by membrane cholesterol amounts and their relation to multidrug resistance in human CEM leukemia cells. Biochemistry. 2005;44:4499–4509. doi: 10.1021/bi048669w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garrigues A., Escargueil A. E., Orlowski S. The multidrug transporter, P-glycoprotein, actively mediates cholesterol redistribution in the cell membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:10347–10352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162366399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Troost J., Albermann N., Emil Haefeli W., Weiss J. Cholesterol modulates P-glycoprotein activity in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;316:705–711. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Troost J., Lindenmaier H., Haefeli W. E., Weiss J. Modulation of cellular cholesterol alters P-glycoprotein activity in multidrug-resistant cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004;66:1332–1339. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.002329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kioka N., Tsubota J., Kakehi Y., Komano T., Gottesman M. M., Pastan I., Ueda K. P-glycoprotein gene (MDR1) cDNA from human adrenal: normal P-glycoprotein carries Gly185 with an altered pattern of multidrug resistance. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1989;162:224–231. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)91985-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kimura Y., Shibasaki S., Morisato K., Ishizuka N., Minakuchi H., Nakanishi K., Matsuo M., Amachi T., Ueda M., Ueda K. Microanalysis for MDR1 ATPase by high-performance liquid chromatography with a titanium dioxide column. Anal. Biochem. 2004;326:262–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takeuchi K., Yokogawa M., Matsuda T., Sugai M., Kawano S., Kohno T., Nakamura H., Takahashi H., Shimada I. Structural basis of the KcsA K(+) channel and agitoxin2 pore-blocking toxin interaction by using the transferred cross-saturation method. Structure. 2003;11:1381–1392. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayward R. D., Cain R. J., McGhie E. J., Phillips N., Garner M. J., Koronakis V. Cholesterol binding by the bacterial type III translocon is essential for virulence effector delivery into mammalian cells. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;56:590–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radhakrishnan A., Sun L. P., Kwon H. J., Brown M. S., Goldstein J. L. Direct binding of cholesterol to the purified membrane region of SCAP: mechanism for a sterol-sensing domain. Mol. Cell. 2004;15:259–268. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chifflet S., Torriglia A., Chiesa R., Tolosa S. A method for the determination of inorganic phosphate in the presence of labile organic phosphate and high concentrations of protein: application to lens ATPases. Anal. Biochem. 1988;168:1–4. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muller M., Bakos E., Welker E., Varadi A., Germann U. A., Gottesman M. M., Morse B. S., Roninson I. B., Sarkadi B. Altered drug-stimulated ATPase activity in mutants of the human multidrug resistance protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:1877–1883. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.4.1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loo T. W., Clarke D. M. Identification of residues in the drug-binding domain of human P-glycoprotein: analysis of transmembrane segment 11 by cysteine-scanning mutagenesis and inhibition by dibromobimane. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:35388–35392. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.50.35388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Modok S., Heyward C., Callaghan R. P-glycoprotein retains function when reconstituted into a sphingolipid- and cholesterol-rich environment. J. Lipid Res. 2004;45:1910–1918. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400220-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gimpl G., Klein U., Reilander H., Fahrenholz F. Expression of the human oxytocin receptor in baculovirus-infected insect cells: high-affinity binding is induced by a cholesterol-cyclodextrin complex. Biochemistry. 1995;34:13794–13801. doi: 10.1021/bi00042a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharom F. J., Yu X., DiDiodato G., Chu J. W. Synthetic hydrophobic peptides are substrates for P-glycoprotein and stimulate drug transport. Biochem. J. 1996;320:421–428. doi: 10.1042/bj3200421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maki N., Hafkemeyer P., Dey S. Allosteric modulation of human P-glycoprotein: inhibition of transport by preventing substrate translocation and dissociation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:18132–18139. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210413200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dey S., Ramachandra M., Pastan I., Gottesman M. M., Ambudkar S. V. Evidence for two nonidentical drug-interaction sites in the human P-glycoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:10594–10599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Loo T. W., Bartlett M. C., Clarke D. M. Simultaneous binding of two different drugs in the binding pocket of the human multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:39706–39710. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308559200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taguchi Y., Morishima M., Komano T., Ueda K. Amino acid substitutions in the first transmembrane domain (TM1) of P-glycoprotein that alter substrate specificity. FEBS Lett. 1997;413:142–146. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00899-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taguchi Y., Kino K., Morishima M., Komano T., Kane S. E., Ueda K. Alteration of substrate specificity by mutations at the His61 position in predicted transmembrane domain 1 of human MDR1/P-glycoprotein. Biochemistry. 1997;36:8883–8889. doi: 10.1021/bi970553v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Loo T. W., Bartlett M. C., Clarke D. M. Transmembrane segment 1 of human P-glycoprotein contributes to the drug binding pocket. Biochem. J. 2006;396:537–545. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sarkadi B., Price E. M., Boucher R. C., Germann U. A., Scarborough G. A. Expression of the human multidrug resistance cDNA in insect cells generates a high activity drug-stimulated membrane ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:4854–4858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.al-Shawi M. K., Senior A. E. Characterization of the adenosine triphosphatase activity of Chinese hamster P-glycoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:4197–4206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sprong H., van der Sluijs P., van Meer G. How proteins move lipids and lipids move proteins. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;2:504–513. doi: 10.1038/35080071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]