Abstract

Loss of self-incompatibility (SI) in Arabidopsis thaliana was accompanied by inactivation of genes required for SI, including S-LOCUS RECEPTOR KINASE (SRK) and S-LOCUS CYSTEINE-RICH PROTEIN (SCR), coadapted genes that constitute the SI specificity-determining S haplotype. Arabidopsis accessions are polymorphic for ΨSRK and ΨSCR, but it is unknown if the species harbors structurally different S haplotypes, either representing relics of ancestral functional and structurally heteromorphic S haplotypes or resulting from decay concomitant with or subsequent to the switch to self-fertility. We cloned and sequenced the S haplotype from C24, in which self-fertility is due solely to S locus inactivation, and show that this haplotype was produced by interhaplotypic recombination. The highly divergent organization and sequence of the C24 and Columbia-0 (Col-0) S haplotypes demonstrate that the A. thaliana S locus underwent extensive structural remodeling in conjunction with a relaxation of selective pressures that once preserved the integrity and linkage of coadapted SRK and SCR alleles. Additional evidence for this process was obtained by assaying 70 accessions for the presence of C24- or Col-0–specific sequences. Furthermore, analysis of SRK and SCR polymorphisms in these accessions argues against the occurrence of a selective sweep of a particular allele of SCR, as previously proposed.

INTRODUCTION

A major transition in the evolutionary history of Arabidopsis thaliana was the adoption of a self-fertile mating system. This transition occurred through loss of self-incompatibility (SI), a genetic barrier to self-pollination that is responsible for the obligate outcrossing mode of mating in the genus Arabidopsis and other genera of the crucifer (Brassicaceae) family. How A. thaliana switched its mating system from outbreeding to inbreeding is of great interest. Analysis of the S locus self-recognition genes S-LOCUS RECEPTOR KINASE (SRK) and S-LOCUS CYSTEINE-RICH PROTEIN (SCR) within the context of the entire S locus is central to understand fully the switch to self-fertility and its molecular implications. The S locus of the Columbia-0 (Col-0) accession was shown to contain nonfunctional ΨSRK and ΨSCR sequences (Kusaba et al., 2001), and two recent studies reported that different A. thaliana accessions were polymorphic for S locus genes (Nasrallah et al., 2004; Shimizu et al., 2004).

It is not known if the S locus sequence polymorphisms observed in A. thaliana reflect polymorphisms already found in distinct functional S haplotypes that were present in a self-incompatible ancestor or if they are the result of differential degradation of the S locus in different self-fertile populations. Arabidopsis lyrata and Arabidopsis halleri, two self-incompatible sister taxa of A. thaliana, have SRK alleles similar to the ΨSRK alleles found in A. thaliana (Bechsgaard et al., 2006), suggesting that these ΨSRKs are derived from distinct ancestral SRK alleles. However, a detailed understanding of the dynamics of S locus evolution and of the events that shaped this locus requires knowledge, not only of the sequences of S locus genes, but also of the configuration of S haplotype variants. A characteristic of functional S haplotypes is that they typically exhibit extensive structural heteromorphisms (i.e., shuffled gene order) and that they contain haplotype-specific sequences (Boyes et al., 1997; Nasrallah, 2000; Kusaba et al., 2001), which are two features that are thought to contribute to reduced recombination in the region and to maintenance of coadapted SI recognition alleles in tight genetic linkage. Consequently, A. thaliana S haplotypes are expected to exhibit structural heteromorphisms that reflect the divergent structures of their progenitor functional S haplotypes as well as rearrangements that might have occurred concomitant with, or after, the switch to self-fertility because of a relaxation of selection for maintaining the integrity and linkage of S locus genes.

At present, the overall organization of the S locus is known only from the completed genome sequence of the A. thaliana Col-0 accession. Among accessions predicted to carry an S haplotype different from the Col-0 haplotype is the C24 accession (Nasrallah et al., 2004). This accession is of particular interest because it is converted to full SI when transformed with A. lyrata S locus recognition genes, indicating that it has not accumulated mutations at SI modifier loci unlike other tested accessions (Nasrallah et al., 2004). Thus, the self-fertile phenotype of C24 is due solely to its nonfunctional S locus, and it is of interest to examine this locus for the presence and organization of SRK and SCR sequences. Here, we report on the comparative analysis of the S locus region in C24 and Col-0. We show that the S haplotype of C24 contains only short and rearranged remnants of SRK and lacks SCR sequences. The data are consistent with the occurrence of interhaplotype recombination and for extensive, possibly transposon-driven, structural remodeling across large segments of the S locus in A. thaliana. By screening 70 accessions for the presence of SRK and SCR and of sequences diagnostic for the S haplotypes of C24 and Col-0, we determine the distribution and frequency of distinct S haplotypes. The results resolve a discrepancy between published reports on the distribution of the Col-0 ΨSCR allele (Nasrallah et al., 2004; Shimizu et al., 2004) and are discussed in relation to hypotheses for the origin of self-fertility in the A. thaliana lineage.

RESULTS

Isolation of the S Locus from the C24 Accession

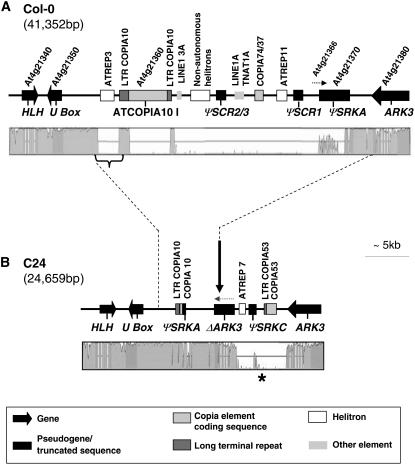

In a previous comparative analysis of A. thaliana and A. lyrata, we established that the S locus of A. thaliana is located on the long arm of chromosome 4 between At4g21350, which encodes a U box–containing protein, and At4g21380, which encodes the ARK3 SRK-like receptor kinase (Kusaba et al., 2001). As shown in Figure 1A, this region of the Col-0 accession is 42 kb in length and is annotated as containing an SRK-like gene (At4g21370), which we designate as ΨSRK, a short sequence similar to 416 bp spanning part of exons 6 and 7 of ΨSRK (At4g21366), and two Ty1-copia-like elements (At4g21360 and At4g21363). In addition to these annotated sequences, and 3′ of the transcriptional unit of ΨSRK, we had also identified three truncated SCR sequences: the 976-bp ΨSCR1 (including intron sequences), the 41-bp ΨSCR2, and the 37-bp ΨSCR3, which are located 590, 8399, and 8339 bp away, respectively, from the stop codon of the predicted ΨSRK open reading frame (Kusaba et al., 2001).

Figure 1.

Structural and Sequence Divergence of the Col-0 and C24 S Locus Haplotypes.

(A) Map of the Col-0 S locus with VISTA diagram depicting the levels of sequence identity to the C24 S haplotype.

(B) Map of the C24 S locus with VISTA diagram depicting the levels of sequence identity to the Col-0 S haplotype. The vertical arrow indicates the recombination breakpoint inferred to have occurred between a ΨSRKA-containing and a ΨSRKC-containing S haplotype. The orientation (5′ to 3′) of the ΔARK3 sequence is shown by the stippled arrow.

The maps show the S locus region, defined as the genomic region flanked by At4g21340 and At4g21380. The stippled lines between the Col-0 and C24 maps define the region of correspondence between the two maps. Annotated sequences and transposon-related elements are depicted according to the legend in the box. The regions in the VISTA diagrams shown in dark gray indicate coding regions. The bracket in (A) and the asterisk in (B) mark the ATREP3 and the CCOP regions, respectively, used as markers for the polymorphism studies summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

We had previously shown that the A. thaliana C24 accession hybridizes with a probe derived from the Col-0 ΨSRK exon 1 but not with a Col-0 ΨSCR1 probe, and it does not produce PCR amplification products with primers designed to either Col-0 ΨSRK or ΨSCR sequences (Nasrallah et al., 2004). These results suggest that C24 contains an S locus haplotype different from that of Col-0. They also show that the C24 genome lacks sequences identical or closely related to Col-0 ΨSCR sequences at the S locus or elsewhere in the genome. To examine the structure of the S haplotype in C24, we isolated the S locus region from a BAC library constructed from C24 genomic DNA (see Methods). We obtained high-quality and continuous sequence (see Methods) for the region between At4g21340 and At4g21380 with the exception of one small gap (see below), which we were unable to bridge despite repeated efforts, probably because of its repetitive nature. As shown in Figure 1B, the C24 S haplotype, bounded by At4g21340 and At4g21380, is 24.6 kb in length. Only 68% of this sequence shares high nucleotide identity (97% or greater) with the Col-0 S haplotype, while the remainder of the sequence exhibits little or no similarity to Col-0. Much of the size difference between the C24 and Col-0 S haplotypes is due to two insertion/deletions: one spanning a 2078-bp segment that in Col-0 is annotated as noncoding sequence separating the U-box gene At4g21350 from the Ty1-copia-like element At4g21360, and another consisting of a segment ∼18 kb in size, which in Col-0 contains most of the Ty1-copia-like element At4g21360, ΨSCR2/3, ΨSCR1, Ty1-copia element At4g21363, At4g21366, and most of ΨSRK (At4g21370).

Rearrangements, Deletions, and Duplications in the C24 S Locus

As predicted from our previous PCR and DNA gel blot analysis (Nasrallah et al., 2004), the C24 S haplotype differs from the Col-0 S haplotype with respect to SRK and SCR sequences. Importantly, it lacks ΨSCR1-related sequences. Furthermore, as shown in Figures 1B and 2A, it contains only small and rearranged remnants of SRK that, unexpectedly, appear to be derived from two different ΨSRK alleles, the Col-0 ΨSRK allele and a ΨSRK allele similar to that found in the Kr-0 (CS6764) accession, which belong to ΨSRK haplogroups A and C, respectively, of Shimizu et al. (2004). Hereafter, to avoid confusion with the term S haplotype, which refers to the entire S locus region, we use the terms ΨSRKA, ΨSRKB, and ΨSRKC instead of ΨSRK haplogroups A, B, and C, and we refer to the corresponding S haplotypes as Sa, Sb, and Sc.

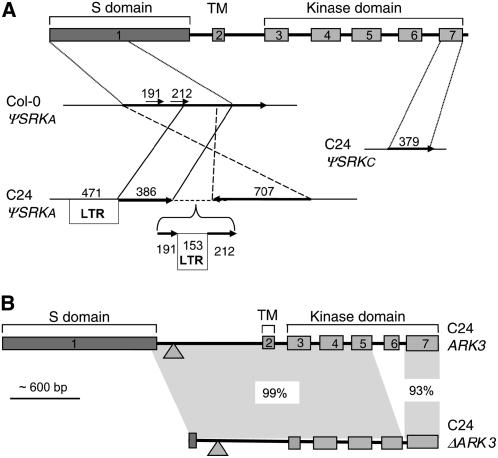

Figure 2.

Magnified View of the ΨSRK and ARK3 Sequences of the C24 S Haplotype.

(A) ΨSRK sequences. The organizations of the ΨSRKA and ΨSRKC sequences are shown in comparison to a diagrammatic view of the intron-exon structure of an SRK gene (top diagram). Regions of sequence identity are joined by diagonal or vertical lines, arrows indicate the relative orientation of the segments, and numbers above the arrows indicate the length of each segment. Note that the C24 ΨSRKC sequences correspond to exon 7, which explains the fact that C24 genomic DNA does not hybridize with a probe derived from ΨSRKC exon 1 (Table 2). The C24 ΨSRKA sequences, which correspond to 875 bp starting with the initiating ATG codon in exon 1, are highly rearranged relative to Col-0 ΨSRKA and are interspersed with LTR sequences. The unanchored contig in the C24 ΨSRKA sequence (see text) is indicated by a bracket.

(B) Duplicate ARK3 sequences. The diagram compares the structures of the complete ARK3C24 gene and the truncated ΔARK3C24 sequence. The stippled triangles indicate the location of a 54-bp deletion found in both genes relative to ARK3Col-0. The extent of sequence identity shared by different regions of the two genes is indicated.

The Kr-0–like ΨSRK sequence in C24 (ΨSRKC, Figures 1B and 2A) consists of 327 bp derived from the 3′ end of SRK and is identical to exon 7 of the ΨSRKC allele in the Kr-0 accession. On the other hand, the Col-0–like ΨSRK sequences (ΨSRKA, Figures 1B and 2A) consist of four short noncontiguous segments that are identical to a continuous stretch of 875 bp at the N terminus of the Col-0 ΨSRKA S domain. The C24 ΨSRKA sequences are rearranged relative to the corresponding sequences of Col-0 ΨSRKA, and they are interspersed with sequence similar, but not identical, to portions of the Col-0 Ty1-copia element At4g21360 (see below). This ΨSRKA region also contains a 556-bp unanchored contig consisting of a long terminal repeat (LTR) flanked by ΨSRKA sequence (Figure 2A) and a gap in the sequence, which is estimated to be <100 bp in length based on the relative lengths of the cloned region and the available DNA sequence. This short region does not contain ΨSCR1 sequences, however, because the BAC insert and subclones spanning it did not hybridize with a ΨSCR1 probe (data not shown). These results explain the distinct restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) patterns we previously observed for Col-0 and C24 upon hybridization with a ΨSRKA S domain probe (Nasrallah et al., 2004). They also explain our failure to amplify ΨSRK or ΨSCR sequences from C24, which lacks sequences complementary to one (ΨSRKA) or both (ΨSRKC and ΨSCR) of our PCR primer pairs.

Another distinguishing feature of the C24 S haplotype is the presence of a truncated ARK3 sequence in addition to a complete version of the ARK3 gene At4g21380 at the boundary of the S locus (Figure 1B). This truncated ARK3 sequence, designated ΔARK3C24, lacks most of exon 1 and all of exon 6 with parts of its flanking introns (Figure 2B). To understand the origin of this duplication, we compared the complete ARK3 gene in C24 (ARK3C24) and ΔARK3C24 to ARK3 sequences from Col-0 (ARK3Col-0) and other accessions. Based on a haplotype network (see Supplemental Figure 1 online), ARK3Col-0 and ARK3C24 are among the most diverged ARK3 sequences available, with nucleotide identities ranging from 91 to 96% across the gene. Interestingly, the 5′ end of ΔARK3C24 up to the site of the exon 6 deletion is 99% identical to ARK3C24, and it shares with this full-length copy a 54-bp deletion in intron 1 relative to ARK3Col-0 (Figure 2B). By contrast, exon 7 of ΔARK3C24 is only 93% identical to exon 7 of ARK3C24 but 100% identical to exon 7 of ARK3Col-0, even though the remainder of ΔARK3C24 shares only 92 to 96% nucleotide identity with the corresponding regions of ARK3Col-0. Thus, ΔARK3C24 is clearly a chimeric sequence.

This observation prompted us to determine if exon 7 of ARK3C24 is similar to that of ARK3 genes in other accessions. Because ARK3 exon 7 sequences were not available, we amplified and sequenced 193 bp of the ∼327-bp exon 7 from seven additional accessions, four containing ΨSRKC (Ra-0, Ita-0, Kas-2, and Br-0), two containing ΨSRKA (Nd-0 and Rld), and Cvi-0, which contains ΨSRKB. We found that, for the sequence analyzed, exon 7 of ARK3C24 is identical to exon 7 of ARK3 in all four ΨSRKC-containing accessions, and these accessions differ by seven single nucleotide polymorphisms from the corresponding region of ARK3 in ΨSRKA-containing accessions (see Supplemental Figure 2 online). Furthermore, the sequence similarity to Col-0 extends into the region 3′ of ΔARK3C24, which shares 97% nucleotide identity with the ΨSRK-ARK3 intergenic sequence in Col-0. By contrast, a 1738-bp segment 3′ of ARK3C24, which contains ΨSRKC-like sequences, is not found in the Col-0 S haplotype but rather exhibits ∼97% nucleotide identity with the corresponding region in the ΨSRKC-containing Kas-2 S haplotype (C. Tang and M. Nordborg, personal communication). The simplest interpretation of these sequence relationships is that the C24 S haplotype is the product of a recombination event between a ΨSRKA-containing and a ΨSRKC-containing S haplotype. This recombination event, with a breakpoint within intron 5, 13 bp 5′ of exon 6 of ΔARK3C24, would explain the similarity of the C24 S haplotype to Col-0 on the side of the breakpoint toward At4g21340 and its similarity to ΨSRKC-containing S haplotypes on the other side of the breakpoint toward ARK3.

Transposon-Related Sequences in the S Locus of C24 and Col-0

The Col-0 and C24 S haplotypes differ in the number and type of transposon-related sequences they contain. One difference relates to a Ty1-copia element annotated as At4g21360 in the Col-0 sequence. In the C24 S locus, the coding region of this element is deleted (Figure 1B), leaving only LTR sequence and a 70-bp segment that shares 98% nucleotide identity with the region between the LTR and the polyprotein sequence of the Col-0 element (Figure 1B).

Additional differences were uncovered by analysis of the Col-0 and C24 S locus sequences using the transposon-finding program CENSOR (Jurka et al., 2005). This analysis revealed that the Col-0 S locus contains several truncated transposon-related sequences not found in the C24 locus (Figure 1A). Between the U-box gene At4g21350 and At4g21360 (i.e., within the 2078-bp sequence that is absent in C24; Figure 1A), is a sequence with 97% similarity to the ATREP3 family of nonautonomous helitrons. Furthermore, the Col-0 locus contains sequences that exhibit between 66 and 89% similarity to various other elements, including two LINEs, three nonautonomous helitrons (two ARNOLDY-like and one ATREP11-like elements), two DNA elements (an ATHAT and a TNAT), and two Ty1-copia elements (ATCOPIA74 and 37) (Figure 1A). Conversely, the C24 locus contains transposon-related fragments that are not found in the Col-0 locus (Figure 1B). These include a sequence that shares ∼78% similarity with ATREP7, a nonautonomous helitron that occurs at many sites in the Col-0 genome and is also adjacent to ΨSRKC in the Kas-2 accession (C. Tang and M. Nordborg, personal communication), and a Ty1-copia-like element that exhibits 85 to 89% similarity to ATCOPIA53 over 145 bp of the LTR and 1.3 kb of the coding region. Overall, transposon-like sequences account for 11,557 and 2754 bp of DNA, or ∼27 and ∼12% of overall size, in the Col-0 and C24 S haplotypes, respectively.

Dating the Divergence of the C24 and Col-0 S Haplotypes

Two sets of sequences allowed us to date some of the events that shaped the C24 and Col-0 S loci: the LTRs of the At4g21360 copia-like element and the duplicated ARK3 sequences in C24. Dating the insertion of an LTR retrotransposon is based on accumulated differences between its two LTR sequences, with the assumption that the LTRs were identical at the time of insertion (SanMiguel et al., 1998). We followed the convention of previous papers (Devos et al., 2002; Pereira, 2004) and used the synonymous substitution rate of 1.5 × 10−8 mutations per site per year as determined for CHS and ADH in the Brassicaceae (Koch et al., 2000). The At4g21360 copia-like element in Col-0 has nearly identical LTR sequences, and the few observed differences suggest that the insertion of this element was a recent event that occurred within the last 140,000 years (±70,000). There are no differences in the LTRs remaining in C24, but if the most complete LTR from C24 is compared with the LTRs in Col-0, the divergence of the two S haplotypes dates back to more than 100,000 years ago (133,000 or 200,000 years ago depending on which Col-0 LTR is used in the comparison, with large standard errors of ±100,000 to 150,000 years, respectively). By contrast, comparison of the ΔARK3C24 sequence through exon 5 with the corresponding regions of ARK3C24 suggests that these sequences diverged very recently (sometime in the past 17,000 ± 17,000 years). However, a more ancient origin for the ARK3 duplication cannot be discounted. The presence of two ARK3 sequences in C24 might reflect the occurrence of two copies of ARK3 in the ancestral Sc haplotype, similar to the duplicated ARK3 genes found in some functional S haplotypes of A. lyrata (Hagenblad et al., 2006), and the high nucleotide identity between ARK3C24 and ΔARK3C24 might be due to the homogenizing effect of gene conversion. A structural analysis of various Sc-derived haplotypes should help resolve this issue.

Distribution of S Haplotype Variants in Natural Populations of A. thaliana

Comparative analysis of the C24 and Col-0 S haplotypes provided us with sequences found in one but not the other haplotype, which could be used in conjunction with ΨSRK and ΨSCR sequences to assess the distribution of S haplotype variants in A. thaliana. To this end, we surveyed 70 accessions by amplification and gel blot analysis of genomic DNA. The 70 accessions were first subjected to PCR using primer pairs specific for each of the three known ΨSRK alleles. As shown in Table 1, 42 accessions produced an amplification product (33 with ΨSRKA primers, one with ΨSRKB primers, and eight with ΨSRKC primers), indicating that they carried a relatively intact ΨSRK allele. By contrast, 28 accessions, including C24, failed to produce an amplification product with any of the ΨSRK primer pairs. However, these accessions produced a hybridization signal with a ΨSRK S domain probe, as shown in Figure 3 and Table 2, suggesting that they contained ΨSRK sequences that lacked regions complementary to the primers used, either due to truncation or sequence divergence. Among these accessions, 26 hybridized with a ΨSRKA probe, producing either a C24-like RFLP pattern (16 accessions) or a distinctive pattern (10 accessions) (Table 2), while two accessions hybridized with a ΨSRKC probe but produced an RFLP pattern different from other ΨSRKC-containing accessions (Table 2).

Table 1.

Survey of A. thaliana Accessions That Produce Amplification Products with SRKA, SRKB, or SRKC Primers

| ΨSRKa

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABRC No. | Name | Geographical Origin | A | B | C | ΨSCR1b | ATREP3c | CCOPd |

| 1092 | Col-0 | Germany/U.S. | + | A1 (0.5 and 0.6 kb) | 3 kb | − | ||

| 20 | Ler-0 | + | A1* | 3 kb | − | |||

| 913 | RLD | Russia | + | A1 | 3 kb | − | ||

| 22605 | Tamm-27 | Finland | + | A1 | 3 kb | − | ||

| 22655 | Ms-0 | Moscow | + | A1 | 3 kb | − | ||

| 915 | Ws | Russia | + | A1* | 1 + 3 kb | − | ||

| 1150 | Est-1 | Russia | + | A1 | 3 kb | + | ||

| 1212 | Gu-1 | Germany | + | A1 | 3 kb | + | ||

| 1394 | No-0 | Germany | + | A1 | 3 kb | + | ||

| 1640 | Tsu | Japan | + | A1 | 3 kb | + | ||

| 6926 | Tsu1 | Japan | + | A1* | 3 kb | + | ||

| 22604 | Tamm-2 | Finland | + | A1 | 3 kb | + | ||

| 22606 | KZ1 | Kazakhstan | + | A1 | 3 kb | + | ||

| 22624 | Yo-0 | U.S. | + | A1 | 3 kb | + | ||

| 1124 | Ei-2 | Russia | + | A1 | 1 kb | − | ||

| 1390 | Nd-0 | Germany | + | A1 | 1 kb | − | ||

| 3109 | Ber | Denmark | + | A1 | 1 kb | − | ||

| 22659 | Ws-2 | Ukraine | + | A1 | 1 kb | − | ||

| 1602 | Ws-0 | Ukraine | + | A1 | 1 kb | + | ||

| 22567 | Knox-18 | U.S. | + | A1 | 1 kb | + | ||

| 22584 | Omo2-1 | Sweden | + | A1 | 1 + 2 kb | + | ||

| 22574 | Lov-1 | N. Sweden | + | A2 (0.5 and 0.9 kb) | 1 kb | + | ||

| 22575 | Lov-5 | N. Sweden | + | A2 | 1 kb | + | ||

| 22643 | Nok-3 | Netherlands | + | A2 | 1 kb | + | ||

| 22576 | Fab-2 | Sweden | + | A2 | 1 kb | − | ||

| 22579 | Bil-7 | Sweden | + | A2 | 1 kb | − | ||

| 22581 | Var2-6 | Sweden | + | A2 | 1 kb | − | ||

| 22583 | Spr1-6 | Sweden | + | A2 | 1 kb | − | ||

| 22586 | Ull2-5 | Sweden | + | A2 | 1 kb | − | ||

| 22580 | Var2-1 | Sweden | + | A2 | − | + | ||

| 1500 | Sah-0 | Spain | + | A3 (1 kb) | 1 kb | − | ||

| 954 | Bay-0 | Germany | + | A4 (−) | 1 kb | + | ||

| 6179 | Hodja | Tajikistan | + | A4 | 1 kb | − | ||

| 1096 | Cvi-0 | Cape Verde Islands | + | −* | 1 kb | + | ||

| 1264 | Kas-2 | India | + | −* | 1 kb | + | ||

| 1354 | Lz-0 | France | + | − | 1 kb | + | ||

| 22628 | Br-0 | Czechoslovakia | + | − | 1 kb | + | ||

| 22649 | Pro-0 | Spain | + | ND | 1 kb | + | ||

| 1244 | Ita-0 | Morocco | + | −* | 3 kb | + | ||

| 22632 | Ra-0 | France | + | − | 3 kb | + | ||

| 1372/6795 | Mr-0 | Italy | + | − | − | + | ||

| 22656 | Bur-0 | Ireland | + | − | − | + | ||

PCR using primers for ΨSRKA, ΨSRKB, and ΨSRKC. +, successful amplification; blank boxes, no amplification.

DNA gel blot analysis with the ΨSCR1 probe. A1, A2, and A3: three different ΨSCR1 hybridization patterns (sizes of hybridizing HincII fragments are indicated in parentheses). −, no hybridization signal; ND, not determined. Asterisks indicate accessions that were reported to contain ΨSCR1 by Shimizu et al. (2004).

PCR using primers (see Supplemental Table 1 online) specific for the ATREP3 insertion/deletion (Figure 1A). The sizes of amplification products are shown. −, no amplification.

PCR using primers (see Supplemental Table 1 online) specific for CCOP, a 675-bp product from the region between ΨSRKC and COPIA53 in C24 (Figure 1B). +, successful amplification; −, no amplification.

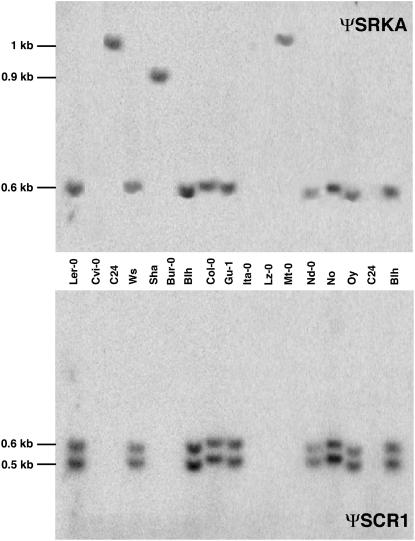

Figure 3.

DNA Gel Blot of Representative A. thaliana Accessions.

Genomic DNA was digested with HincII, and the same DNA gel blot was hybridized with a probe derived from ΨSRKA exon 1 (top panel) and a probe corresponding to ΨSCR1 (bottom panel). Both probes were amplified from the Col-0 S locus BAC T6K22 (see Methods). Note that only accessions that exhibit the same ΨSRKA RFLP pattern as Col-0 hybridize with the ΨSCR1 probe. Accessions that exhibit ΨSRKA RFLP patterns different from Col-0 (C24, Sha, and Mt-0) and those that do not hybridize with the ΨSRKA probe (Cvi-0, Bur-0, Ita-0, and Lz-0) do not hybridize with ΨSCR1.

Table 2.

Survey of A. thaliana Accessions That Failed to Produce Amplification Products with ΨSRKA, ΨSRKB, or ΨSRKC Primers

| ΨSRKa

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABRC No. | Name | Geographical Origin | A | C | ΨSCR1b | ATREP3c | CCOPd |

| 906 | C24 | Portugal | 1 kb | − | − | 1 kb | + |

| 1272/6755 | Kin-0 | U.S. | 1 kb | − | − | 1 kb | + |

| 6173 | Est | Germany | 1 kb | − | − | 1 kb | + |

| 22564 | RRS-7 | U.S. | 1 kb | − | − | 1 kb | + |

| 22568 | Rmx-A02 | U.S. | 1 kb | − | − | 1 kb | + |

| 22603 | CIBC17 | UK | 1 kb | − | − | 1 kb | + |

| 22609 | Goett-22 | Germany | 1 kb | − | − | 1 kb | + |

| 22613 | Uod-7 | Austria | 1 kb | − | − | 1 kb | + |

| 22631 | Gy-0 | France | 1 kb | − | − | 1 kb | + |

| 22650 | LL-0 | Spain | 1 kb | − | − | 1 kb | + |

| 1380/6799 | Mt-0 | Libya | 1 kb | − | − | 1 + 1.2 kb | + |

| 1584/6884 | Van-0 | Canada | 1 kb | − | − | 1 + 1.2 kb | + |

| 22599 | NFA-10 | UK | 1 kb | − | − | 1 + 1.2 kb | + |

| 22634 | Ga-0 | Germany | 1 kb | − | − | 1 + 1.2 kb | + |

| 916 | Kon | Tajikistan | 1 kb | − | − | 1 kb | - |

| 3110 | Wei-0 | Switzerland | 2 kb (A5) | − | − | 1 kb | + |

| 1552/6868 | Ts-1 | Spain | 2 kb (A5) | − | − | 1 kb | + |

| 22566 | Knox-10 | U.S. | 2.2 kb (A5) | − | − | 1 kb | + |

| 22570 | Pna-17 | U.S. | 2.2 kb (A5) | − | − | 1 kb | + |

| 22571 | Pna-10 | U.S. | 2.2 kb (A5) | − | − | 1 kb | + |

| 22572 | Eden-1 | Sweden | 2.2 kb (A5) | − | − | 1 kb | + |

| 22648 | Ts-5 | Spain | 3 kb (A5) | − | − | 1 kb | + |

| 929 | Sha | Tajikistan | 0.9 kb (A5) | − | −* | 1 kb | - |

| 22653 | Sorbo | Tajikistan | 0.9 kb (A5) | − | − | 1 kb | + |

| 922/6178 | Hodja | Tajikistan | 0.9 kb (A5) | − | − | 1 kb | - |

| 22630 | Ag-0 | France | Multiple (A5) | − | −* | 1 + 1.2 kb | + |

| 22565 | RRS-10 | U.S. | − | 3 kb | − | 1 kb | + |

| 22637 | Wt-5 | Germany | − | 1.2 kb | − | − | + |

DNA gel blot analysis with ΨSRKA (A) and ΨSRKC (C) probes showing the approximate sizes of hybridizing HincII fragments. A5, a heterogeneous group of accessions that exhibit a variety of RFLP patterns.

DNA gel blot analysis with the ΨSCR1 probe. −, no hybridization signal. Asterisks indicate accessions that were reported to contain ΨSCR1 by Shimizu et al. (2004).

PCR using primers (see Supplemental Table 1 online) specific for the ATREP3 insertion/deletion (Figure 1A). The sizes of amplification products are shown. −, no amplification.

PCR using primers (see Supplemental Table 1 online) specific for CCOP, a 675-bp product from the region between ΨSRKC and COPIA53 in C24 (Figure 1B). +, successful amplification; −, no amplification.

All 70 accessions were subsequently analyzed for the presence of the Col-0 ΨSCR1 sequence. Because amplification of genomic DNA using several different primers for ΨSCR1 produced artifactual results (see Supplemental Figure 3 online), we performed DNA gel blot analysis using a ΨSCR1 probe amplified from the Col-0 S locus BAC T6K22 (Figure 3). Three different ΨSCR1 RFLP patterns were identified in HincII-digested DNA (Table 1): the A1 pattern, consisting of 0.5- and 0.6-kb fragments, in Col-0 and 20 other accessions derived from various geographical locations; the A2 pattern, consisting of 0.5- and 0.9-kb fragments, in nine accessions, all from northern Europe; and the A3 pattern, consisting of a 2-kb fragment, in one accession from Spain. The larger restriction fragments in the A2 and A3 patterns appear to reflect simple polymorphisms for HincII sites flanking ΨSCR1 rather than differences in the sequence of ΨSCR1. Indeed, inverse PCR and sequencing of the region 3′ of an ΨSCR1 A2 allele demonstrated that it contained the same premature stop codon and downstream sequences as Col-0 ΨSCR1. Importantly, our analysis showed that the ΨSCR1 probe hybridized only with ΨSRKA-carrying accessions (Figure 3, Tables 1 and 2). Not all ΨSRKA-containing accessions contained ΨSCR1 sequences, however. Two accessions that produced amplification products with primers for ΨSRKA (the A4 group in Table 1) and 10 accessions that exhibited a variety of distinct ΨSRKA hybridization patterns (the A5 group in Table 2) failed to hybridize with the ΨSCR1 probe.

The accessions were also analyzed using two sets of primers to regions that differ between the Col-0 and C24 S haplotypes. One set of primers was designed to bracket a region in the Col-0 S haplotype containing the 2-kb ATREP3 helitron and 1-kb of intergenic sequence (Figure 1A). These primers produce a 3-kb amplification product (ATREP3 column in Tables 1 and 2) in Col-0 and a 1-kb product in C24, which lacks the ATREP3 sequence (Figure 1B). Another set of primers was designed from within a 1278-bp unique sequence that lacks significant matches to the Col-0 genome sequence and lies between ΨSRKC and the Ty-copia element (COPIA53) in C24 (Figure 1B). These primers produce a 675-bp amplification product (referred to as CCOP in Tables 1 and 2) in C24 but fail to produce an amplification product in Col-0 (Tables 1 and 2). When used for amplification of DNA from different accessions, these primers produced either the C24 or Col-0 amplification patterns, with a few exceptional accessions exhibiting two, rather than one, amplification products with the ATREP3 primers (Tables 1 and 2). Interestingly, there was little correlation between polymorphisms at ΨSRK/ΨSCR, ATREP3, and CCOP (Tables 1 and 2).

DISCUSSION

Our comparative analysis of the Col-0 and C24 S haplotypes presents a picture of the S locus region as a dynamic region of the A. thaliana genome that has experienced restructuring and decay in microsynteny and gene content. In contrast with Col-0, which has retained the relatively intact, albeit nonfunctional, ΨSRKA allele as well as remnants of SCR, the much smaller S haplotype of C24 contains only short segments of ΨSRKA and, unexpectedly, of ΨSRKC, and it lacks SCR sequences. The two S haplotypes also differ in the number and classes of transposon-related sequences, the presence of haplotype-specific sequences, and a partial duplication in C24 of the flanking ARK3 gene.

Possible Events Underlying the Structural Divergence of S Haplotypes

A major challenge in understanding the diversification of S haplotypes in A. thaliana, including the S haplotype of C24, is to relate the observed differences in sequence and structure to events that occurred either before or after the switch to self-fertility. In this context, it is important to note that each of the two phases of the evolutionary history of the A. thaliana S locus is a source for structural variability. In the first phase that predates the switch to self-fertility, selective pressure for maintenance of the linkage and integrity of the SRK and SCR recognition genes would favor a reduced rate of recombination effected by sequence and structural divergence, as described in self-incompatible Brassica and A. lyrata strains (Boyes et al., 1997; Nasrallah, 2000; Kusaba et al., 2001; Kamau and Charlesworth, 2005; Hagenblad et al., 2006). In this phase, the S locus, like other genomic regions that exhibit suppressed recombination (Steinemann and Steinemann, 2005; Uyenoyama, 2005; Fujimoto et al., 2006), would have been a sink for transposons and would have accumulated haplotype-specific sequences resulting from independent evolution and degeneration of noncoding sequences over time. In the second phase occurring after loss of SI, selective pressures would be relaxed, allowing for decay of the locus and its recognition genes and increased rates of recombination within the region. Thus, accounts of the evolutionary history of the A. thaliana S locus must distinguish between structural differences already present in the ancestral functional S haplotypes from which extant haplotypes were derived and those resulting from independent decay of nonfunctional S haplotypes in isolated self-fertile populations. While achieving this level of understanding requires the cloning and sequencing of S haplotypes from many accessions, some insight is provided by a comparison of the Col-0 and C24 S haplotypes described here.

Evidence for Structural Heteromorphisms Descended from Ancestral S Haplotypes

Because the S haplotype of C24 appears to be the product of a recombination event that occurred in an individual heterozygous for a Col-0–like Sa and a Kr-0–like Sc haplotype (Figures 1B and 2A), differences that distinguish the Sc-derived segment of the C24 S haplotype from both its Sa-derived segment and the Col-0 S haplotype likely reflect in large part structural differences passed down from ancestral functional S haplotypes. For example, the sequence between the duplicated ARK3 genes, which contains a nonautonomous ATREP7 helitron, must have been present in the progenitor Sc haplotype because it is not present in the S locus of Col-0 but is found near the 3′ end of the ΨSRKC sequence in the Kas-2 S locus.

Evidence for Decay in S Locus Structure following the Switch to Self-Fertility

Other features of the S haplotype of C24 are likely related to decay of the locus after the switch to self-fertility. In particular, the numerous differences observed between the Sa-derived segment in C24 and the Col-0 S haplotype, including the At4g21363 Ty1-copia element and helitron, LINE, and DNA elements, which along with much of ΨSRKA and all ΨSCR sequences are missing from C24, likely resulted from a deletion in the C24 lineage rather than an insertion in the Col-0 lineage. This deletion of ∼18 kb of DNA might have been caused by illegitimate recombination between the LTRs of two retrotransposon elements, a process that is known to cause deletion of the internal sequences of the elements along with the intervening sequence between the elements (Devos et al., 2002; Ma et al., 2004; Vitte and Panaud, 2005).

Transposon-driven events might also have generated other distinguishing features of the S haplotype in C24, but these events are difficult to date without additional characterization of the S locus in many more accessions. In particular, retrotransposon-induced events might have produced the solo LTR of the ATCOPIA53 element located between the duplicated ARK3 sequences in the Sc-derived segment. Additionally, the presence of helitron-related sequences in both the C24 and Col-0 S haplotypes suggests a role for this class of transposons in shaping the S locus. Helitrons, whose mechanism of replication and transposition is thought to cause the excision of exons and introns and their insertion in a shuffled order at various locations across the genome (Kapitonov and Jurka, 2001; Brunner et al., 2005b, 2005a; Morgante et al., 2005), are now thought to have been responsible, along with LTR retrotransposons, for many cases of intraspecific violation of genetic colinearity in plants (Boyes et al., 1997; Bennetzen, 2000; Fu and Dooner, 2002; Joobeur et al., 2004; van der Knaap et al., 2004; Scherrer et al., 2005). Although this type of helitron activity has not been reported in A. thaliana, possibly because it does not produce easily identifiable molecular footprints, it is possible that helitrons were responsible for some of the rearrangements seen in the C24 S locus.

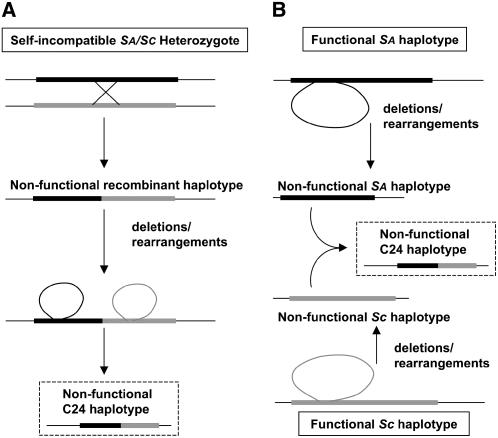

Because of the complex structure of the C24 S haplotype and the lack of information on the structure of additional S haplotypes, especially Sc-derived haplotypes, it is difficult to infer with any degree of certainty the exact nature and sequence of events that generated this haplotype. Nevertheless, two possible scenarios are depicted in Figure 4. A recombination event in a self-incompatible SaSc individual might have disrupted the linkage of matched SRK and SCR alleles, producing a nonfunctional recombinant S haplotype, with subsequent rearrangements and deletion of SCR and most of SRK sequences resulting at least in part from transposon activity (Figure 4A). Alternatively, deletions and rearrangements might have independently produced nonfunctional Sa and Sc haplotypes, causing self-fertility (Figure 4B). Subsequently, these nonfunctional S haplotypes would have been brought together by cross-hybridization between self-fertile individuals and then recombined to produce the chimeric C24 S haplotype (Figure 4B). In this context, it should be noted that self-fertility does not preclude cross-hybridization, and there is evidence that gene flow via pollen contributes to genetic variability within local populations of A. thaliana (Bakker et al., 2006).

Figure 4.

Two Possible Scenarios for the Generation of the C24 S Haplotype.

(A) Recombination between Sa and Sc haplotypes in a heterozygous self-incompatible individual, causing loss of SI and subsequent restructuring of the locus mediated at least in part by transposons.

(B) Inactivation of the Sa and Sc haplotypes by rearrangements and deletions, at least partly transposon-driven, followed by recombination in a self-fertile heterozygous individual. The S haplotypes in which the initial inactivating events are proposed to have occurred are shown in boxes with solid lines. The C24 S haplotypic configuration is shown in boxes with dashed lines.

S Haplotype Polymorphisms

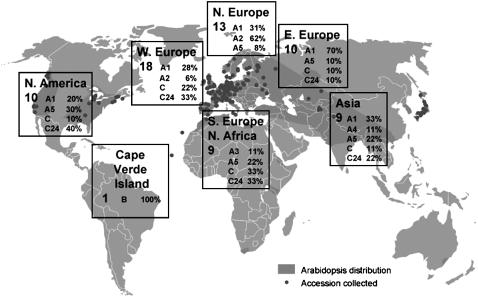

The C24 S haplotype, or versions very similar to it, is estimated to occur in ∼23% of A. thaliana accessions. This estimate derives from a survey of 70 accessions and is based on identical ΨSRK and ΨSCR DNA gel blot hybridization patterns, results of DNA amplification with various primers, and presence of sequences found in the C24 S haplotype but missing in Col-0 (Tables 1 and 2). The same survey of 70 accessions revealed that 33 accessions (or 47%) carried Sa-derived haplotypes, 11 accessions carried the Sc haplotype, and only one accession (Cvi-0) carried the Sb haplotype. While this result confirms previous reports (Nasrallah et al., 2004; Shimizu et al., 2004) that Sa-derived haplotypes are the most prevalent in the species, it remains possible that this relatively high frequency might simply reflect overrepresentation of sampled accessions from areas where Sa-derived haplotypes predominate, as illustrated in Figure 5. In any case, the Sa-derived class of haplotypes appears to have undergone substantial intrahaplotype diversification, in some cases specific to certain geographical regions, allowing further subdivision into at least six subtypes (Tables 1 and 2, Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Geographical Distribution of S Locus Variants.

The frequencies of different S haplotypes (designated as in Tables 1 and 2) in each of seven geographical areas are expressed as a percentage of accessions surveyed from each area (indicated by the number at the left side of each box). The map (obtained from www.natural-eu.org) shows the worldwide distribution of A. thaliana (dark shading) and the location of accessions available through seed stock centers (dots). Note that the distribution of different subtypes of the Sa class of haplotypes is consistent with independent diversification in different geographical areas. In particular, S haplotypes belonging to the A1 or A5 subtypes, which likely invaded Europe from Asia, apparently differentiated into the A2 subtype in western and northern Europe and into the A3 subtype in southern Europe.

In all, our analysis has identified eight major S haplotypic configurations in the species on the basis of polymorphisms in ΨSRK and ΨSCR and at least 20 configurations if differences in ATREP3 and CCOP are also considered. This number may be an underestimate because the actual number can only be determined accurately from detailed structural analyses of the S locus in different accessions. Furthermore, it is not known if some of the divergent S haplotypes, particularly those from accessions that failed to produce amplification products with ΨSRKA, ΨSRKB, or ΨSRKC primers (Table 2), contain SRK alleles descended from ancestral haplotypes with SI specificities other than Sa, Sb, and Sc. Future sequencing and comparative studies of these A. thaliana S haplotypes and of additional A. lyrata S haplotypes will no doubt help answer this question. Such interspecific structural comparisons are also important for two other reasons. First, they might reveal which structural features existed before loss of SI and which arose in conjunction with the switch to self-fertility. Second, they might allow the identification of additional SCR alleles and their inactive A. thaliana remnants, both of which are difficult to isolate by standard cloning methods because of their extensive polymorphisms.

Notably, our survey of A. thaliana accessions revealed significant assortment between ΨSRK, ATREP3, and CCOP sequences (Tables 1 and 2). Although further detailed analysis is required to confirm that ATREP3 and CCOP sequences are indeed located at the S locus in each of the accessions surveyed, this observation, together with the recombinant nature of the S haplotype in C24, suggests that recombination events have occurred multiple times in the S locus region. This conclusion is supported by a recent study involving a cross between the Col-0 and Ler-0 accessions, which identified the S locus region as one of 10 recombination hotspots on chromosome 4 (Drouaud et al., 2006). However, Col-0 and Ler-0 share the same or highly similar S haplotypes according to our survey (Tables 1 and 2), and much lower frequencies of recombination at the S locus are expected in crosses between accessions carrying more diverged S haplotypes. For example, analysis of ∼3000 F2 progenies derived from a cross between C24 and RLD (which carries a Col-0–like S haplotype) identified only one recombinant between the S locus flanking genes At4g21350 and At4g21380 (P. Liu, S. Sherman-Broyles, M.E. Nasrallah, and J.B. Nasrallah, unpublished data). Thus, although recombination in the S locus region might have increased in conjunction with the switch to self-fertility in A. thaliana, subsequent restructuring of the locus as described here for C24 will, in practice, translate into low recombination frequencies in crosses between some accessions.

Alternative Hypotheses for the Evolution of Selfing in A. thaliana

Despite evidence for the occurrence of recombination in the S locus region, we failed to identify recombination between ΨSRK and ΨSCR1. In our sampling of 70 accessions, ΨSCR1 was detected only in accessions containing ΨSRKA sequences and not in those carrying ΨSRKB or ΨSRKC (Tables 1 and 2), confirming our previous results from a more limited survey of 27 accessions (Nasrallah et al., 2004). These results differ from those of Shimizu et al. (2004), who reported amplification of ΨSCR1 sequences from all 21 accessions analyzed, irrespective of whether they carried the ΨSRKA, ΨSRKB, or ΨSRKC allele. Furthermore, the ΨSCR1 amplification products obtained in that study were essentially identical, with four silent nucleotide substitutions detected in 881 sites analyzed (Shimizu et al., 2004). Six of the 21 accessions analyzed in the Shimizu et al. (2004) study were also represented in our survey (indicated by asterisks in Tables 1 and 2), and three of these (Cvi-0, Kas-2, and Ita-0) did not hybridize with the ΨSCR1 probe (Table 1). Thus, our data do not support the hypothesis proposed by Shimizu et al. (2004) that a selective sweep of the nonfunctional ΨSCR1 allele caused the transition to self-fertility in A. thaliana. Doubts about this hypothesis were also previously raised on the basis of population genetic considerations (Charlesworth and Vekemans, 2005).

At present, it is not evident that the S locus is the only selfing locus that was subjected to positive selection for self-fertility in the species. Rather, the fixation in different A. thaliana accessions of independent inactivating mutations at the S locus as shown here and at cryptic SI modifier loci as revealed by interspecific complementation with A. lyrata SRKb-SCRb genes (Nasrallah et al., 2002, 2004) suggests the involvement of mutations at several loci required for SI. The switch to selfing might have occurred independently in distinct small populations, where any gene that promotes selfing is expected to have a strong selective advantage. The mutation causing self-fertility might have occurred at the S locus in some populations (as in C24) and at one or more SI modifier locus in others. These mutations would have occurred relatively recently, according to date estimates provided here and those reported by Shimizu et al. (2004) and Bechsgaard et al. (2006). However, it is important to keep in mind that these reported dates are only estimates for the time of inactivation of S locus recognition genes and not for the time of the transition to self-fertility. In any case, a prediction of this hypothesis is that one or more functional S haplotypes would have persisted in some populations after the switch to self-fertility. Although further tests are required, such intact S haplotypes are unlikely to have survived to this date, however, because SRK and SCR have SI-specific functions. By contrast, functional alleles at SI modifier loci would have persisted in some populations because they might be required under certain conditions for processes unrelated to SI. This possibility is supported by the fact that, while SRK and SCR are expressed exclusively in stigma and anthers, respectively, at least some SI modifier loci exhibit ubiquitous expression (Murase et al., 2004; P. Liu, S. Sherman-Broyles, M.E. Nasrallah, and J.B. Nasrallah, unpublished data).

The geographical pattern of S haplotype distribution provides further support for the hypothesis that self-fertility resulted from mutations at both the S locus and modifier loci, rather than strictly from mutations at the S locus, because the latter are expected to produce a distribution with much stronger geographical structure than is observed. The distribution of S haplotypes is also consistent with the hypothesis that A. thaliana colonized central and northern Europe from Pleistocene glacial refugia in the Mediterranean and Asia (Sharbel et al., 2000; Hoffmann et al., 2003). Postglacial migration from these refugia would have been accompanied by the invasion of different allelic variants into newly colonized areas. If we exclude accessions whose distribution is thought to result from recent human activity, such as the North American accessions and Kas (Vander Zwan et al., 2000), our results support the following general scenario. The Sa haplotype and the Sc haplotype appear to have been sheltered in the Asian and Mediterranean refugia, respectively, while the Sb haplotype persisted in the isolated Cape Verde Islands to which it remains restricted (Figure 5). Multiple independent losses of SI within each of these three geographical locations or in conjunction with postglacial colonization, followed by subsequent independent differentiation or decay in different areas, would largely explain the observed distribution of S haplotypes (Figure 5). Under this scenario, suture zones where Sa-containing accessions from Asia and Sc-containing accessions from the Mediterranean came in contact would have provided the opportunity for hybridization between accessions and the generation of recombinant S haplotypes, such as C24.

This overall scheme is consistent with the data and with the expectation that populations of an ephemeral species like A. thaliana would undergo frequent cycles of extinction and recolonization (Bergelson et al., 1998). However, an unequivocal understanding of how A. thaliana made the switch to self-fertility will require detailed analysis of the genetic architecture of selfing in the species, identification of SI modifier loci, sequencing of divergent S locus haplotypes, determining if any functional S haplotypes persist, and sampling of more accessions to confirm hypotheses relating to A. thaliana's geographic history.

METHODS

Plant Material

Seed from C24 (CS906) and other accessions listed in Tables 1 and 2 were obtained from the ABRC. The C24 accession had once been referred to as Columbia (Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre; http://arabidopsis.info/) but has since been distinguished from Col-0 based on polymorphisms for several molecular markers.

Construction and Screening of a C24 BAC Library and Sequence Analysis of the C24 S Locus Region

A large insert library was constructed in the pBeloBAC vector using genomic DNA from Arabidopsis thaliana accession C24 according to previously described procedures (Woo et al., 1994). The library was screened using a probe corresponding to the S locus flanking gene At4g21350, which was generated by amplification from the Col-0 BAC T6K22 (see Supplemental Table 1 online for PCR primers). Three positive overlapping BAC clones were identified. The 60-kb insert of one clone, BAC26J14, was determined by end-sequencing to extend from the At4g21323 gene into the third exon of the At4g21380 (ARK3) gene. BAC26J14 DNA was digested with SstI, and each of the resulting five fragments was subcloned into the pZero2 vector (Invitrogen). Subclones were end-sequenced using M13 universal primers complementary to vector sequences, and three subclones were identified as spanning the S locus by BLAST searches of the National Center for Biotechnology Information database. The inserts of these three subclones were sequenced by primer walking, and the junctions between subclones were bridged using DNA from BAC26J14 and from an EcoRV subclone that spanned the SstI junctions. Because BAC26J14 contained only a partial ARK3 gene lacking exons 1 and 2, the remaining portions of ARK3 were amplified from a BAC that contained a longer insert to confirm that a complete ARK3 gene flanked the C24 S locus.

Sequencing was performed on an Applied Biosystems automated 3730xl DNA analyzer with big dye terminator chemistry and AmpliTaq-FS DNA polymerase at the BioResource Center at Cornell University. Contigs were assembled using the SeqMan program and aligned using ClustalW (both part of the DNASTAR Lasergene6 package. Aligned DNA sequences were analyzed using the DnaSP package (Rozas et al., 2003) downloaded from http://www.ub.es/dnasp/. Distance matrices were calculated using MEGA3 (Kumar et al., 2004). VISTA diagrams were generated using programs at http://genome.lbl.gov/vista/index.shtml. Sequences were screened for similarity to transposable elements using the CENSOR program (Jurka et al., 2005) at http://www.girinst.org/.

Amplification of S Locus Sequences

For PCR of ΨSRK, we used our previously described primers (Nasrallah et al., 2004) and primers described by Shimizu et al. (2004). Specific primer sequences are listed in Supplemental Table 1 online. To determine the molecular basis of the A2 ΨSCR1 RFLP, an inverse PCR approach was used. After determining by DNA gel blot analysis that ΨSCR1 A2 sequences were contained on a 2.5-kb XbaI fragment, genomic DNA was digested with XbaI and self-ligated. The mixture was then amplified and sequenced using ΨSCR1-specific primers (inverse PCR primers are listed in Supplemental Table 1 online).

DNA Gel Blot Analysis

DNA from each accession was digested with HincII, run on 0.8% (w/v) agarose gels, transferred to Hybond N+ membranes (Amersham Biosciences) using an alkaline transfer method, and hybridized with 32P-labeled probes prepared with the Random Priming kit (Roche). ΨSRKA and ΨSRKC probes were prepared from PCR fragments corresponding to exon 1, which encodes the extracellular domain of SRK. ΨSRKA and ΨSCR1 PCR fragments were generated using the S locus–spanning Col-0 BAC T6K22 as template to avoid possible contamination by spurious PCR products that might result from amplification of genomic DNA, especially in the case of ΨSCR1 (see Supplemental Figure 3 online). The ΨSRKC probe was a gel-purified PCR product obtained by amplification of genomic DNA from the Kas accession (primers KASsF and KASsR in Supplemental Table 1 online).

ARK3 Gene Network

The Splitstree 4 program (Huson and Bryant, 2006; http://www-ab.informatik.uni-tuebingen.de/software/splitstree4/welcome.html) was used to create a network depicting genetic distances among available ARK3 sequences (GenBank accession numbers AY772560 to AY772579).

Sequence Divergence

LTR sequences were aligned as noncoding sequences and distances calculated using MEGA version 3.1 (Kumar et al., 2004). The Kimura two-parameter test was used with the pairwise deletion option to determine distance, and standard error was calculated using the analytical option. Genetic distances were used to estimate the date of insertion using the formula t = K/2r, where t = time, K is genetic distance, and r is nucleotide substitution rate. The synonymous substitution rate of 1.5 × 10−8 mutations per site per year as determined for CHS and ADH in the Brassicaceae (Koch et al., 2000) was used. Similarly, ΔARK3 sequences were assumed to be noncoding, and the same formula was used to determine the date of most recent common ancestor of the ARK3 sequences.

Accession Number

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession number EF182720.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Table 1. Primers Used to Amplify Specific Genes for Phylogenetic Analysis and for Use as Probes.

Supplemental Figure 1. Haplotype Network of ARK3 Sequences.

Supplemental Figure 2. Alignment of ARK3 Exon 7 Sequences from Various Accessions.

Supplemental Figure 3. ΨSCR1 Amplification Artifacts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Tom Brutnell for the inverse PCR protocol and Jeff Doyle and Steve Kresovich for critical reading of early versions of the manuscript. Seed for A. thaliana accessions were obtained from the ABRC. This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation under Grant 0414521.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantcell.org) is: June B. Nasrallah (jbn2@cornell.edu).

Online version contains Web-only data.

References

- Bakker, E.G., Stahl, E.A., Toomajian, C., Nordborg, M., and Kreitman, M. (2006). Distribution of genetic variation within and among local populations of Arabidopsis thaliana over its species range. Mol. Ecol. 15 1405–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechsgaard, J., Castric, V., Charlesworth, D., Vekemans, X., and Schierup, M.H. (2006). The transition to self-compatibility in Arabidopsis thaliana and evolution within S-haplotypes over 10 million years. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23 1741–1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennetzen, J. (2000). Comparative sequence analysis of plant nuclear genomes: Microcolinearity and its exceptions. Plant Cell 12 1021–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergelson, J., Stahl, E.A., Dudek, S., and Kreitman, M. (1998). Genetic variation within and among populations of Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics 148 1311–1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyes, D.C., Nasrallah, M.E., Vrebalov, J., and Nasrallah, J.B. (1997). The self-incompatibility (S) haplotypes of Brassica contain highly divergent and rearranged sequences of ancient origin. Plant Cell 9 237–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner, S., Fengler, K., Morgante, M., Tingey, S., and Rafalski, A. (2005. b). Evolution of DNA sequence nonhomologies among maize inbreds. Plant Cell 17 343–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner, S., Pea, G., and Rafalski, A. (2005. a). Origins, genetic organization and transcription of a family of non-autonomous helitron elements in maize. Plant J. 43 799–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth, D., and Vekemans, X. (2005). How and when did Arabidopsis become highly self-fertilising. Bioessays 27 472–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devos, K.M., Brown, J.K.M., and Bennetzen, J.L. (2002). Genome size reduction through illegitemate recombination counteracts genome expansion in Arabidopsis. Genome Res. 12 1075–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drouaud, J., Camilleri, C., Bourguignon, P.-Y., Canaguier, A., Berard, A., Vezon, D., Giancola, S., Brunel, D., Colot, V., Quesneville, H., and Mezard, C. (2006). Variation in crossing-over rates across chromosome 4 of Arabidopsis thaliana reveals the presence of meiotic recombination “hot spots”. Genome Res. 16 106–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, H., and Dooner, H.K. (2002). Intraspecific violation of genetic colinearity and its implications in maize. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99 9573–9578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto, R., Okazaki, K., Fukai, E., Kusaba, M., and Nishio, T. (2006). Comparison of the genome structure of the self-incompatibility (S) locus in interspecific pairs of S haplotypes. Genetics 173 1157–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagenblad, J., Bechsgaard, J., and Charlesworth, D. (2006). Linkage disequilibrium between incompatibility locus region genes in the plant Arabidopsis lyrata. Genetics 173 1057–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, M.H., Glab, A.S., Tomiuk, J., Schmuths, H., Fritsch, R.M., and Bachmann, K. (2003). Analysis of molecular data of Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. (Brassicaceae) with geographical information systems. Mol. Ecol. 12 1007–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huson, D.H., and Bryant, D. (2006). Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23 254–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joobeur, T., King, J.J., Nolin, S.J., Thomas, C.E., and Dean, R. (2004). The fusarium wilt resistance locus Fom-2 of melon contains a single resistance gene with complex features. Plant J. 39 283–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurka, J., Kapitonov, V.V., Pavlicek, A., Klonowski, P., Kohany, O., and Walichiewicz, J. (2005). Repbase Update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 110 462–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamau, E., and Charlesworth, D. (2005). Balancing selection and low recombination affect diversity near the self-incompatibility loci of the plant Arabidopsis lyrata. Curr. Biol. 15 1773–1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapitonov, V.V., and Jurka, J. (2001). Rolling-circle transposons in eukaryotes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98 8714–8719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch, M., Haubold, B., and Mitchell-Olds, T. (2000). Comparative evolutionary analysis of chalcone synthase and alcohol dehydrogenase loci in Arabidopsis, Arabis and related genera (Brassicaceae). Mol. Biol. Evol. 17 1483–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S., Tamura, K., and Nei, M. (2004). MEGA3: Integrated software for Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis and sequence alignment. Brief. Bioinform. 5 150–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusaba, M., Dwyer, K., Hendershot, J., Vrebalov, J., Nasrallah, J.B., and Nasrallah, M.E. (2001). Self-incompatibility in the genus Arabidopsis: Characterization of the S locus in the outcrossing A. lyrata and its autogamous relative A. thaliana. Plant Cell 13 627–643. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J., Devos, K.M., and Bennetzen, J. (2004). Analyses of LTR-retrotransposon structures reveal recent and rapid genomic DNA loss in rice. Genome Res. 14 860–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgante, M., Brunner, S., Pea, G., Fengler, K., Zuccolo, A., and Rafalski, A. (2005). Gene duplication and exon shuffling by helitron-like transposons gnerate intraspecies diversity in maize. Nat. Genet. 37 997–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murase, K., Shiba, H., Iwano, M., Che, F.S., Watanabe, M., Isogai, A., and Takayama, S. (2004). A membrane-anchored protein kinase involved in Brassica self-incompatibility signaling. Science 303 1516–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrallah, J.B. (2000). Cell-cell signaling in the self-incompatibility response. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 3 368–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrallah, M.E., Liu, P., and Nasrallah, J.B. (2002). Generation of self-incompatible Arabidopsis thaliana by transfer of two S locus genes from A. lyrata. Science 297 247–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrallah, M.E., Liu, P., Sherman-Broyles, S., Boggs, N., and Nasrallah, J. (2004). Natural variation in expression of self-incompatibility in Arabidopsis thaliana: Implications for the evolution of selfing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101 16070–16074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, V. (2004). Insertion bias and purifying selection of retrotransposons in the Arabidopsis thaliana genome. Genome Biol. 5 R79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozas, J., Sanchez-DelBarrio, J.C., Messeguer, X., and Rozas, R. (2003). DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics 19 2496–2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SanMiguel, P., Gaut, B.S., Tikhonov, A., Nakajima, Y., and Bennetzen, J.L. (1998). The paleontology of intergene retrotransposons of maize. Nat. Genet. 20 43–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer, B., Isidore, E., Klein, P., Kim, J.-s., Bellec, A., Boulos, C., Keller, B., and Feuillet, C. (2005). Large intraspecific haplotype variability at the Rph7 locus results from rapid and recent divergence in the barley genome. Plant Cell 17 361–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharbel, T.F., Haubold, B., and Mitchell-Olds, T. (2000). Genetic isolation by distance in Arabidopsis thaliana: Biogeography and postglacial colonization of Europe. Mol. Ecol. 9 2109–2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu, K.K., Cork, J.M., Caicedo, A.L., Mays, C.A., Moore, R.C., Olsen, K.M., Ruzsa, S., Coop, G., Bustamante, C.D., Awadalla, P., and Purugganan, M.D. (2004). Darwinian selection on a selfing locus. Science 306 2081–2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinemann, S., and Steinemann, M. (2005). Retroelements: Tools for sex chromosome evolution. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 110 134–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uyenoyama, M.K. (2005). Evolution of tight linkage to mating type. New Phytol. 165 63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Knaap, E., Sanyal, A., Jackson, S.A., and Tanksley, S.D. (2004). High-resolution fine mapping and fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of sun, a locus controlling tomato fruit shape, reveals a region of the tomato genome prone to DNA rearrangements. Genetics 168 2127–2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Zwan, C., Brodie, S.A., and Campanella, J.J. (2000). The intraspecific phylogenetics of Arabidopsis thaliana in worldwide populations. Syst. Bot. 25 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Vitte, C., and Panaud, O. (2005). LTR retrotransposons and flowering plant genome size: Emergence of the increase/decrease model. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 110 91–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.-S., Jiang, J., Gill, B.S., Patterson, A.H., and Wing, R.A. (1994). Construction and characterization of a bacterial artificial chromosome libary of Sorghum bicolor. Nucleic Acids Res. 22 4922–4931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.