Abstract

The ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) 1 and ATM- and Rad3-related (ATR) protein kinases are crucial regulatory proteins in genotoxic stress response pathways that pause the cell cycle to permit DNA repair. Here we show that Chk1 phosphorylation in response to hydroxyurea (HU) and ultraviolet radiation (UV) is ATR-dependent and ATM- and Mre11-independent. In contrast, Chk1 phosphorylation in response to ionizing radiation (IR) is dependent on ATR, ATM, and Mre11. The ATR and ATM/Mre11 pathways are generally thought to be separate with ATM activation occurring early and ATR activation occurring as a late response to double strand breaks. However, we demonstrate that ATR is activated rapidly by IR, and ATM and Mre11 enhance ATR signaling. ATR-ATRIP recruitment to double-strand breaks is less efficient in the absence of ATM and Mre11. Furthermore, IR-induced replication protein A (RPA) foci formation is defective in ATM and Mre11 deficient cells. Thus, ATM and Mre11 may stimulate the ATR signaling pathway by converting DNA damage generated by IR into structures that recruit and activate ATR.

Genome maintenance requires coordination of DNA repair with cell cycle events. ATR and ATM, members of the phosphatidylinositol kinase-like kinase (PIKK) family, are crucial regulatory proteins in genotoxic stress response pathways. Ultimately, ATM/ATR signaling halts the cell cycle to permit DNA repair, or in situations where repair system are overwhelmed they initiate apoptosis (1–3). Although the ATM and ATR kinases phosphorylate some common substrates, they are differentially activated by distinct types of DNA damage. A primary function of the ATR signaling pathway is to monitor DNA replication. When problems arise, ATR phosphorylates and activates the checkpoint kinase Chk1 as well as many other proteins (4,5). Replication surveillance by ATR is accomplished by the recruitment of ATR and its accessory protein ATRIP to regions of RPA-coated single stranded DNA (ssDNA) that are generated by decoupling of helicase and polymerase activities at damaged replication forks (6–8). Direct binding of ATRIP to RPA-coated ssDNA is required for the stable recruitment of the ATR-ATRIP complex to damaged sites (7,9). However, there may be alternative mechanisms by which the ATR-ATRIP complex can recognize damaged DNA other than direct ATRIP-RPA-ssDNA binding (9–14).

In contrast, ATM primarily initiates cellular responses to double strand breaks and is recruited to sites of damage by the Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 (MRN) complex (14–17). Unlike ATR, ATM is not an essential gene, and ATM deficiencies result in a human disease ataxia-telangiectasia (A-T). Cells from A-T patients are sensitive to IR, but not to UV exposure. These observations have led to the general idea that ATM and ATR function in parallel pathways, where cellular response to replicative stress and UV are attributed to ATR; whereas, ATM mediates cellular responses to IR-induced double strand breaks. However, there are several indications that ATR can also respond to double strand breaks. In A-T cells, p53 phosphorylation in response to IR is delayed but not completely abrogated (18,19), and ATR was shown to be selectively responsible for the late phase of p53 phosphorylation (20). The ATR-ATRIP complex is required for maintaining the G2/M checkpoint in response to IR (6,21–23). The ATR-ATRIP complex is also recruited to IR induced intranuclear foci (9,24). Thus, ATR is activated by double strand breaks, although the prevailing model is that this activation may be a late response compared to ATM signaling.

Here we show that Chk1 phosphorylation in response to IR is rapid and ATR-dependent. ATM- and Mre11-deficient cells display defects in ATR-dependent Chk1 phosphorylation. ATR-ATRIP as well as RPA recruitment to double strand breaks are reduced in ATM- and Mre11-deficient cells. Therefore, ATM and Mre11 stimulate ATR-dependent Chk1 phosphorylation by promoting the conversion of DNA damage generated by IR into structures that recruit the ATR-ATRIP complex.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture and siRNA

All cell lines were maintained in DMEM + 7.5% fetal bovine serum. Transfections of siRNA were performed with Oligofectamine (Invitrogen). The 19 base pair siRNA target sequences used are as follows: ATR, CCUCCGUGAUGUUGCUUGA; ATM, GCCUCCAGGCAGAAAAAGA; ATRIP GGUCCACAGAUUAUUAGAU; Mre11, GCUAAUGACUCUGAUGAUA; Rad50 GCUCAGAGAUUGUGAAAUG; and Nbs1 GAAGAAACGUGAACUCAAG. The 19 base pair nonspecific control oligonucleotide target sequence is AUGAACGUGAAUUGCUCAA. All RNA oligonucleotides were purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO).

Drug Treatment and DNA Damage

Hydroxyurea was purchased from Sigma (no. H8627) dissolved in water at 1 M, and stored frozen. Aphidicolin was purchased from Sigma (no. A0781), dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide at 5 mg/ml, and stored at −80 degrees. Etoposide [4′-Demethylepipodophyllotoxin 9-(4,6-O-ethylidene-β-D-glucopyranoside)] was purchased from Sigma (no. E1383) and dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide at 10mg/ml and stored at −20 degrees. Cells were treated with ionizing radiation from a 137Cs source at a dose rate of 1.8 grays/min. UV was administered with a Stratalinker (Stratagene) after cells were washed one time with PBS.

Proteomics analysis

S3 HeLa nuclear extracts were generated from untreated and hydroxyurea treated cells as follows. Briefly, S3 Hela cells were grown in spinner flasks in Joklik’s modified Eagle’s MEM purchased from Irvine Scientific (Santa Ana, CA) supplemented with 5% new born calf serum (Invitrogen), sodium bicarbonate (Sigma no. S3817), and 1X antibiotic/antimycotic (Invitrogen). Cells were harvested by centrifugation and washed twice with PBS. Cells were resuspended in hypotonic buffer (10 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.9), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 M KCl, 0.5 mM DTT), incubated on ice for 10 min, and homogenized. Resulting nuclei were recovered by centrifugation and resuspend in low salt buffer (20 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.9), 25% glycerol, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.02 M KCl, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.5 mM DTT) and extracted by the addition of high salt buffer (20 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.9), 25% glycerol, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1.2 M KCl, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.5 mM DTT). The resulting extract was dialyzed in dialysis buffer (20 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.9), 20% glycerol, 0.1 M KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.5 mM DTT). ATRIP was immunopurified from these extracts as previously described (25) with the following modifications. Immunoprecipitation were washed in 3X in NET buffer [made by combining NETN buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 0.1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Igepal CA-630) with TBS (50mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150mM NaCl) in 1:1 ratio]. Protein were eluted in 8 M urea under conditions that preferentially eluted ATRIP-interacting proteins, but not the ATRIP antibody. As a result, ATRIP, although present was most likely under represented in the eluate. Eluates were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and associated proteins were identified by two-dimensional liquid chromatography coupled tandem mass spectroscopy.

Antibodies and Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed in 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 250 mM NaCl, 0.5% Igepal CA-630, 0.5% Tween-20, 2.5 mM EGTA supplemented with 5 kg/ml aprotinin, 5 kg/ml leupeptin, 1 mM NaF, 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM sodium vanadate, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation prior to protein concentration determination (Bio-Rad). The ATRIP antibody has been previously described (6). Antibodies to Chk1 and ATR were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; Chk1 PS317 and Chk1 PS345 antibody from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA); ATM, Nbs1, and Mre11 from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO); Rad50 from GeneTex (San Antonio, TX); and ATM pS1981 antibody from Rockland Immunochemicals (Gilbertsville , PA).

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence was performed by plating cells directly on glass coverslips. For quantitation of Mre11 and RPA foci in Hela cells, cells were washed twice with PBS, pre-extracted by a 5 minute incubation on ice in MTSB buffer (10 mM piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid), 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2 ,5 mM EGTA, 100 mM Sucrose, 0.2% Triton X-100), followed by a 2 min incubation on ice in CSB buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2 0.1% Tween 20), washed twice with PBS + 0.1% Triton X-100, washed twice in PBS, and fixed in methanol prior to permeabilization in Triton X-100 solution. HeLa cells analyzed for ATRIP foci and all other cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with Triton X-100 solution as described previously (25). Fluorescein isothiocyanate- and rhodamine red-X-conjugated secondary antibodies were obtained from Jackson Immunoresearch.

RESULTS

Mre11 and ATM are required for ATR-dependent Chk1 phosphorylation in response to IR, but are dispensable in response to UV and HU

Mre11, Nbs1, and Rad50 were identified in an ATRIP complex using a proteomics screen to identify novel ATRIP-associated proteins. Co-immunoprecipitation and size exclusion fractionation of total HeLa cell lysates suggested there may be an association between the MRN and ATR/ATRIP complexes (Supplementary figure 1). However, the percentage of the MRN complex found in ATR or ATRIP immunoprecipitates was small (less than 1%) and the percentage of ATR-ATRIP complex found in immunoprecipitates of the MRN complex was similarly small. Furthermore, the association occurred in untreated cells, was not altered by DNA damage, and we were unable to detect a direct interaction between purified proteins (data not shown). Yet, there have been some reports of a connection between the MRN complex and ATR signaling (26–28); therefore, we decided to investigate the role of the MRN complex in the ATR response to genotoxic stress.

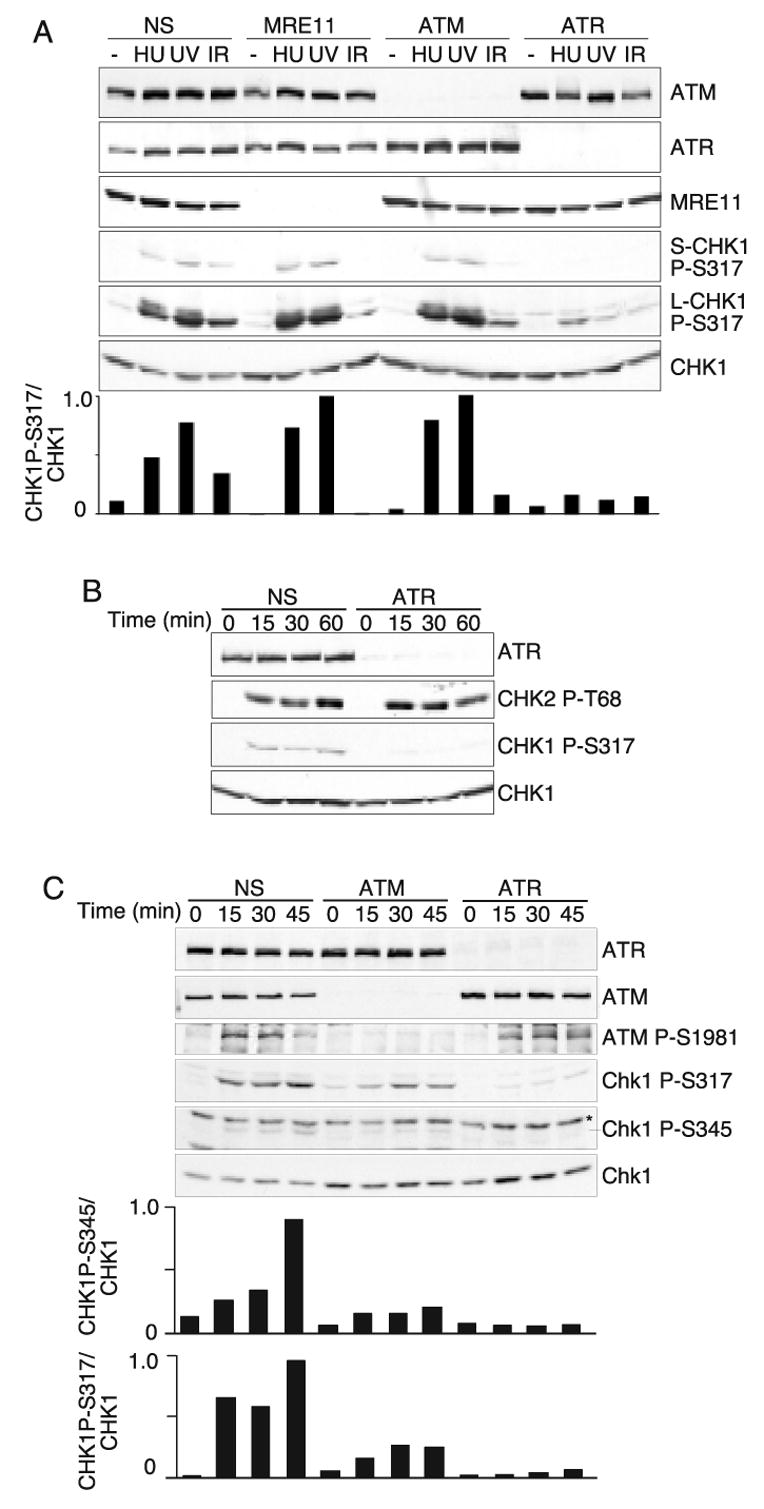

Using RNA interference, we tested the role of Mre11 in ATR signaling to genotoxic stress in HeLa cells. HeLa cells transfected with non-specific siRNA oligonucleotides or siRNA targeting Mre11, or ATR mRNA were exposed to HU (1mM for 5hrs), UV (50j/m2 for 2hr), or IR (5 Gy for 1hr). As expected, we found that ATR is required to phosphorylate Chk1 on S317 in response to HU and UV, but Mre11 is dispensable (Fig 1A). We also observed no role for the ATM kinase in the HU and UV responses. However, knockdown of Mre11, ATM, and ATR all decreased IR-induced Chk1 phosphorylation with ATR knockdown being most severe and the Mre11 and ATM knockdowns giving intermediate defects (Fig 1A).

Fig. 1.

ATM, ATR, and Mre11 are all required for Chk1 phosphorylation in response to IR. (A) Cells were transfected with non-specific siRNA or siRNA targeting Mre11, ATM, or ATR. Three days after transfection, the cells were exposed to 1mM HU for 5 hours, 50J/m2 UV then incubated for 2 hours, or 5Gy of IR followed by a one hour incubation. Cell lysates were prepared, separated by SDS-PAGE, then immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. S-Chk1 is a short exposure and L-Chk1 is a long exposure of the same blot. The quantitation of the Chk1 P-S317 signal compared to total Chk1 for this experiment is shown (arbitrary units). These blot are representive of several consistent experiments. (B and C) Cells transfected with non-specific siRNA or siRNA targeting ATR or ATM were exposed to 5Gy or IR then harvested at the indicated times. Cell lysates were prepared, separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (*cross-reacting protein band in the Chk1 P-S345 blot). The quantitiation of the Chk1 P-S317 or the Chk1 P-S345 signal compared to total Chk1 for this experiment is shown (arbitrary units).

The requirement for both ATM and ATR for Chk1 phosphorylation after IR treatment suggested one of three models. First, ATM and ATR may independently target Chk1; second, ATR may be upstream of ATM; or third, ATM may be upstream of ATR. If ATM and ATR independently targeted Chk1 then we would expect that similar to other ATM substrates, ATM would be required for the early response and ATR the late response to IR. However, ATR is essential for Chk1 phosphorylation even at the earliest time points we were able to process in which the time from initial irradiation to cell lysis was only 15 minutes (Fig 1B). Furthermore, if ATM and ATR were acting in parallel pathways then co-depletion of both ATM and ATR should further decrease Chk1 phosphorylation. However, cells in which both ATM and ATR were depleted showed no further decrease in Chk1 phosphorylation beyond the decrease caused by ATR depletion (supplementary Fig. 2). These results suggest that ATM and ATR function in a common signaling pathway to phosphorylate Chk1 in response to IR. The dependency for both ATM and ATR was not limited to Chk1 S317 phosphorylation as both are also required for Chk1 S345 phosphorylation (Fig. 1C). Consistent with current ATM activation models, we saw no requirement for ATR in the activation of ATM since both Chk2 T68 and ATM S1981 phosphorylation occurred normally in ATR-depleted cells (Fig. 1B and C). Thus, this data support the third model in which ATM acts upstream of ATR, but only in response to double strand breaks.

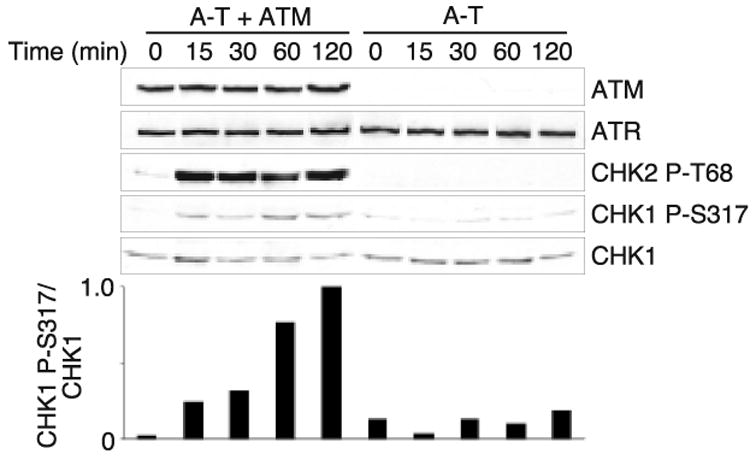

The ATM requirement for Chk1 phosphorylation was also observed in A-T cells. A-T cells or A-T cells complemented with the ATM cDNA were harvested at different time points after ionizing radiation exposure (5Gy) and analyzed for Chk1 phosphorylation. Again, these ATM-deficient cells displayed a defect in Chk1 phosphorylation; whereas, in A-T cells complemented with functional ATM, Chk1 phosphorylation was restored (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

IR-induced Chk1 phosphorylation is defective in cells from A-T patients. A-T or ATM complemented A-T cells (38) were exposed to 5 Gy of IR and harvested at the indicated time points. Cell lysates were prepared, fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. The quantitation of the Chk1 P-S317 signal compared to total Chk1 for this experiment is shown (arbitrary units).

The involvement of ATM and Mre11 in Chk1 phosphorylation appeared limited to IR treatment. For example, there was no Mre11 requirement for Chk1 activation when cells were treated with the DNA polymerase alpha inhibitor aphidicolin or the topisomerase II inhibitor etoposide (supplementary Fig. 3A). The requirement for ATM and Mre11 was not unique to HeLa cells since depletions in U2OS cells yielded similar results. Furthermore, depletion of the other members of the MRN complex, Rad50 and Nbs1, gave similar results as the Mre11 depletion (supplementary Fig. 3A and 3B). Collectively, these data suggest that ATM and the MRN complex may promote optimal ATR activation but only in response to ionizing radiation.

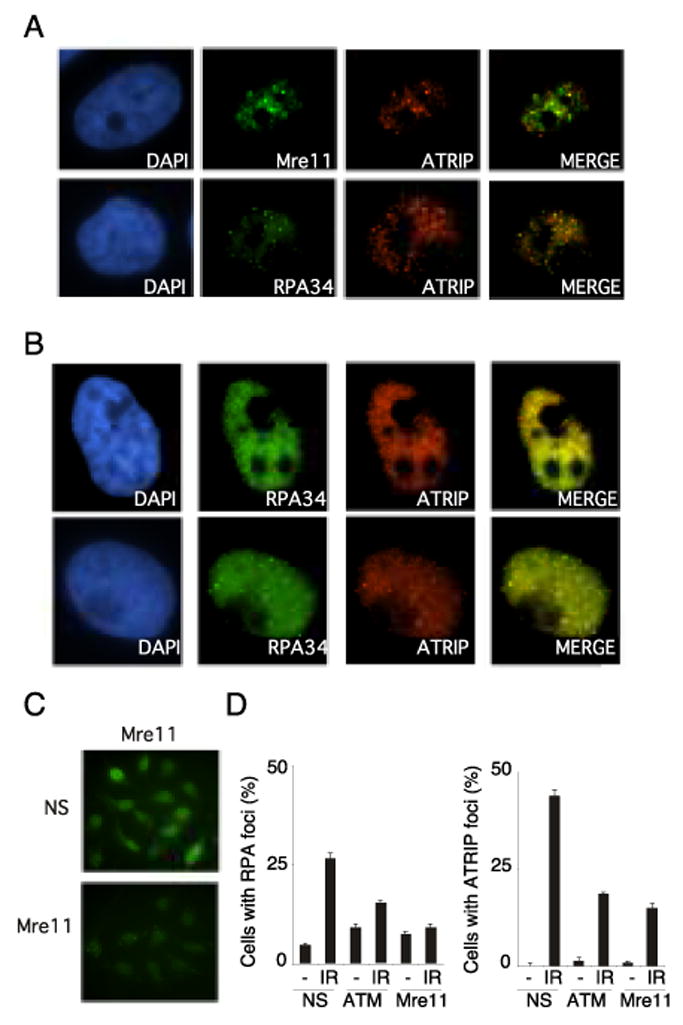

Mre11 and ATM enhance RPA and ATR-ATRIP foci formation in response to IR

ATR activation is believed to require the generation of ssDNA coated with the ssDNA-binding protein RPA (29). Therefore, we hypothesized that ATM and Mre11 may be important for converting double strand breaks generated by IR into DNA structures that recruit and activate ATR. To determine if ATM and Mre11 are required to generate ssDNA at IR-induced double strand breaks, we monitored RPA and ATRIP foci formation in HeLa cells transfected with nonspecific siRNA oligonucleotides or siRNA targeting Mre11 and ATM. After transfection, cells were either left untreated or treated with 5 Gy of IR and fixed for immunofluorescence 1hr after exposure. ATRIP and RPA foci were then monitored by indirect immunofluorescence. In U2OS, HeLa, and ATM complemented A-T cells Mre11, ATRIP and RPA were found to co-localize in response to ionizing radiation (Fig. 3A, 3B, and 4A). Time course analysis indicated that the Mre11 foci accumulated more rapidly than the ATRIP foci (data not shown). A parallel reduction in RPA and ATRIP foci formation was seen in both ATM and Mre11 siRNA depleted cells (Fig. 3D). Only 18.5% of cells depleted of ATM contained ATRIP foci and 15.5% contained RPA foci, similarly 15% of cells depleted of Mre11 contained ATRIP foci and 9% contained RPA foci, while 44% and 26.5% of cells transfected with non-specific oligonucleotides contained ATRIP and RPA foci respectively. Therefore ATM and Mre11 may enhance ATR-ATRIP recruitment to double strand breaks by increasing the amount of RPA-coated ssDNA.

Fig. 3.

IR-induced ATRIP and RPA foci formation is deficient in Mre11 and ATM depleted cells. (A) U2OS cells were exposed to 5 Gy IR and incubated for 1hr. After which cells were fixed in paraformaldehyde, permeabalized, and then immunostained with Mre11, ATRIP and RPA34 antibodies antibodies. After incubation with appropriate rhodamine and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated secondary antibodies, fluorescent images were captured on a Zeiss Axioplan microscope. Each image is representative of the immunostaining in the cell population. (B) HeLa cells left untreated (top) or exposed to 5 Gy IR were and incubated for one hour (bottom) immunostained for Mre11, ATRIP, and RPA34. (C) HeLa cells transfected with non-specific siRNA or siRNA targeting Mre11 were immunostained with Mre11 antibody and processed for immunofluorescence as described above. Images were captured using an equal exposure time to show relative Mre11 levels in non-specific and Mre11 siRNA treated cells. (D) HeLa cells transfected with non-specific siRNA or siRNA targeting Mre11 and ATM were exposed to 5 Gy IR. One hour after exposure RPA34 and ATRIP foci were detected. Quantitation of ATRIP and RPA34 foci in HeLa cells transfected with non specific siRNA or siRNA targeting Mre11 and ATM was done in cells processed for immunofluoresecence one hour after exposure to 5 Gy IR. Error bars represent standard error between experiments.

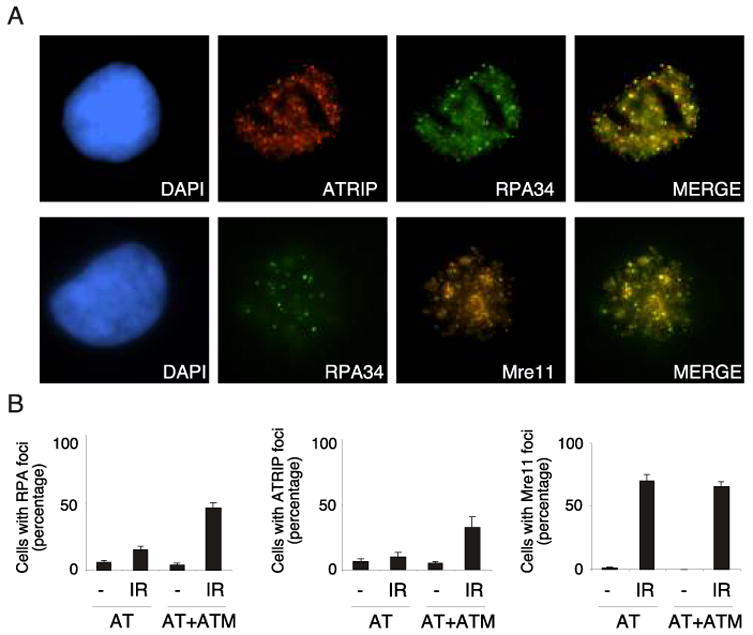

Fig. 4.

Defects in ATRIP and RPA foci in A-T cells are restored by complementation with ATM A-T or ATM complemented A-T cells (38) were exposed to 5 Gy of IR and processed for immunofluorescence with the indicated antibodies one hour after exposure. (A) Representative immunofluorescence images demonstrating ATRIP, RPA34, and Mre11 foci are shown. These images also demonstrate the colocalization of these proteins at IR-induced foci. (B) Quantitation of ATRIP and RPA34 foci in A-T or ATM complemented A-T cells. Error bars represent standard error between experiments.

To confirm that these results were not specific to HeLa cells transfected with siRNA oligonucleotides, RPA and ATRIP foci formation was also monitored in A-T cells and A-T cells complemented with functional ATM. Consistent with the defect observed in ATM-depleted HeLa cells, A-T cells displayed defects in both ATRIP and RPA foci formation in response to IR exposure relative to A-T cells complemented with functional ATM (Fig. 4B). Only 10% of cells without ATM contained ATRIP foci and 15% contained RPA foci. In contrast 32.5% and 46% of A-T cells complemented with functional ATM contained ATRIP and RPA foci respectively. In addition, Mre11 foci formation occurred independently of ATM, as seen by no observable difference in the percentage of cells containing Mre11 foci in A-T and ATM-complemented A-T cells. Therefore, there was no difference in the actual number of double strand breaks in the A-T or ATM-complemented AT cells. Taken together these results suggest that both Mre11 and ATM contribute to optimal activation of ATR by promoting the generation of RPA-coated ssDNA and thereby promoting the recruitment of ATR-ATRIP complexes to sites of double strand breaks.

DISCUSSION

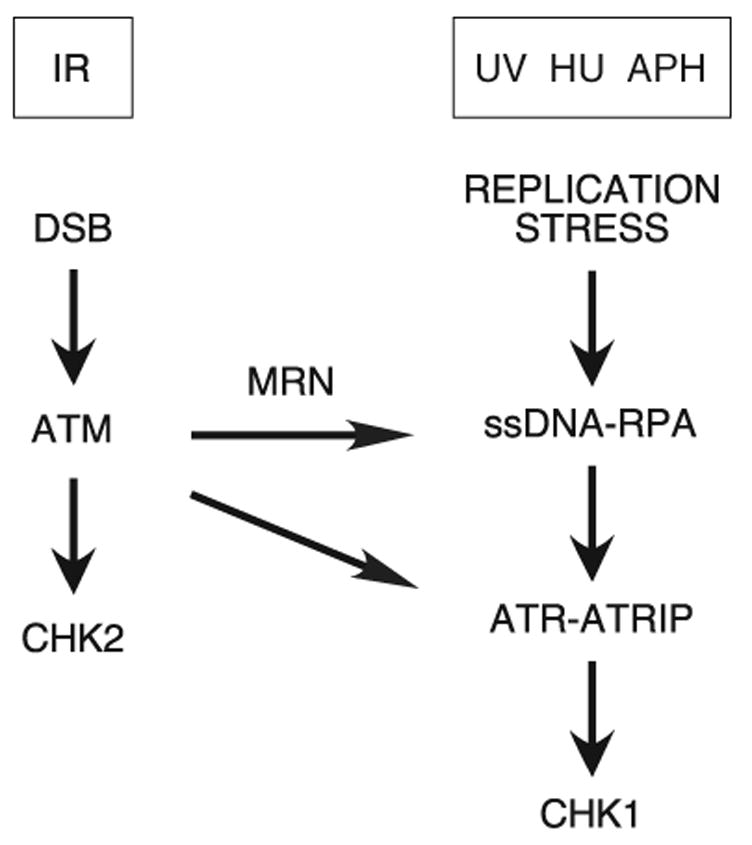

Our results demonstrate that Chk1 is rapidly phosphorylated in response to IR in an ATR-dependent manner. ATM- and Mre11-deficient cells display defects in Chk1 phosphorylation, suggesting that the ATR, ATM, and Mre11 proteins function in a common signaling pathway. The requirement of both Mre11 and ATM is unique to IR-induced ATR-dependent Chk1 phosphorylation and dispensable in ATR-dependent phosphorylation of Chk1 in response to UV and agents that induce replicative stress. Moreover, our data also suggest that Chk1 is largely an ATR substrate as Chk1 phosphorylation is abrogated in ATR-deficient cells which contain active ATM, and depletion of both ATM and ATR does not further impair Chk1 phosphorylation beyond that observed by ATR depletion alone. Thus, we have identified a novel role for ATM upstream of the ATR signaling pathway (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Model of ATR and ATM signaling pathways.

One explanation for the role of both Mre11 and ATM in the ATR-dependent response to IR is that both are required for an intact ATM signaling pathway. Mre11 is required for optimal ATM activation (17,30,31). Activation of ATM results in the phosphorylation of several proteins at double strand break sites, including RPA (32,33), which could be important for ATR recruitment and/or activation and subsequent Chk1 phosphorylation. Alternatively, ATM along with the Mre11 nuclease might be involved in processing double strand breaks into structures that support ATR signaling. Our analysis of RPA and ATRIP localization is consistent with this second model since we observed a reduction in RPA and ATR-ATRIP recruitment to foci in ATM- and Mre11-deficient cells.

Recently, the recruitment of the C. elegans ATR homolog, atl-1, to site of DNA damage generated by IR was found to be RPA-and Mre11-dependent. (34) In a separate study, the involvement of the MRX complex in chromatin remodeling at HO nuclease generated DSBs in S. cerevisae, was also reported (35). These observations and our results support a model in which ATM and Mre11 are required to process double strand breaks into ssDNA thereby facilitating RPA binding. The increased RPA-ssDNA generated by ATM and Mre11 promotes ATR-ATRIP recruitment, which results in Chk1 phosphorylation and augments cell cycle checkpoint activation. This model would explain a dual requirement for ATM and ATR to initiate the G2/M checkpoint in response to IR as well as the requirement for ATR to maintain the checkpoint (23). In the absence of ATM and Mre11 function, ATR activation would proceed although with reduced kinetics. This model also reconciles the prevailing idea that ATR is required for the late response to IR with our data indicating that rapid Chk1 activation by IR is ATR-dependent. The main data supporting the late activation of ATR model comes from experiments done in A-T cells showing delayed phosphorylation of substrates such as p53 in response to IR when ATM is absent (18–20). We suggest that the lack of ATM in these experiments delayed both direct ATM-dependent substrate phosphorylation as well as maximal ATR activation.

During the preparation of this manuscript, Jazayeri et al. published results consistent with our findings that both ATM and Mre11 enhance IR induced ATR-dependent Chk1 phosphorylation at least in part through enhancing RPA and ATR recruitment to double strand breaks (36). It will be important to determine how ATM and Mre11 generate the RPA-coated ssDNA. Interestingly, Mre11 is phosphorylated in response to double strand breaks and this phosphorylation activates its nuclease activity (37). Perhaps ATM promotes an Mre11-dependent nuclease activity to generate stretches of ssDNA that recruit and activate ATR. Alternatively, ATM and Mre11 may help recruit other nucleases that process the double strand break to reveal ssDNA. In any case, our results have important implications for how double strand breaks are sensed by the ATM and ATR checkpoint kinases.

Supplementary Material

The abbreviations used are

- ATM

ataxia-telangiectasia mutated

- ATR

ATM and Rad3 related

- A-T

ataxia telangiectasia

- RPA

replication protein A

- Nbs1

Nijmegen breakage syndrome

- MRN

Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1

- HU

hydroxyurea

- UV

ultraviolet

- IR

ionizing radiation

- kDa

kilodalton

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- DSB

double strand break

- Aph

aphidicolin

Footnotes

This work was supported by NCI grants K01CA93701 and RO1CA102729 to D.C. D.C. is also supported by the Pew Scholars Program in the Biological Sciences sponsored by the Pew Charitable Trusts. J.S.M has been supported by training grants T32CA093240 and T32CA09582. We thank Fen Xia for useful discussion. The mass spectrometry was performed in the Vanderbilt proteomics core facility with help from Amy Ham and partial support from the Center in Molecular Toxicology grant PS0 ES000267.

References

- 1.Bakkenist CJ, Kastan MB. Cell. 2004;118:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shiloh Y. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2001;11:71–77. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00159-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sancar A, Lindsey-Boltz LA, Unsal-Kacmaz K, Linn S. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:39–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Q, Guntuku S, Cui XS, Matsuoka S, Cortez D, Tamai K, Luo G, Carattini-Rivera S, DeMayo F, Bradley A, Donehower LA, Elledge SJ. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1448–1459. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao H, Piwnica-Worms H. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:4129–4139. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.13.4129-4139.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cortez D, Guntuku S, Qin J, Elledge SJ. Science. 2001;294:1713–1716. doi: 10.1126/science.1065521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zou L, Elledge SJ. Science. 2003;300:1542–1548. doi: 10.1126/science.1083430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byun TS, Pacek M, Yee MC, Walter JC, Cimprich KA. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1040–1052. doi: 10.1101/gad.1301205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ball HL, Myers JS, Cortez D. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:2372–2381. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-11-1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rouse J, Jackson SP. Mol Cell. 2002;9:857–869. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00507-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Unsal-Kacmaz K, Makhov AM, Griffith JD, Sancar A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6673–6678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102167799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Unsal-Kacmaz K, Sancar A. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1292–1300. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.1292-1300.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bomgarden RD, Yean D, Yee MC, Cimprich KA. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13346–13353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311098200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim SM, Kumagai A, Lee J, Dunphy WG. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:38355–38364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508673200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falck J, Coates J, Jackson SP. Nature. 2005;434:605–611. doi: 10.1038/nature03442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bakkenist CJ, Kastan MB. Nature. 2003;421:499–506. doi: 10.1038/nature01368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uziel T, Lerenthal Y, Moyal L, Andegeko Y, Mittelman L, Shiloh Y. Embo J. 2003;22:5612–5621. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Canman CE, Wolff AC, Chen CY, Fornace AJ, Jr, Kastan MB. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5054–5058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu X, Lane DP. Cell. 1993;75:765–778. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90496-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tibbetts RS, Brumbaugh KM, Williams JM, Sarkaria JN, Cliby WA, Shieh SY, Taya Y, Prives C, Abraham RT. Genes Dev. 1999;13:152–157. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.2.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cliby WA, Roberts CJ, Cimprich KA, Stringer CM, Lamb JR, Schreiber SL, Friend SH. Embo J. 1998;17:159–169. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu X, Tsvetkov LM, Stern DF. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:4419–4432. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.12.4419-4432.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown EJ, Baltimore D. Genes Dev. 2003;17:615–628. doi: 10.1101/gad.1067403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tibbetts RS, Cortez D, Brumbaugh KM, Scully R, Livingston D, Elledge SJ, Abraham RT. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2989–3002. doi: 10.1101/gad.851000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y, Cortez D, Yazdi P, Neff N, Elledge SJ, Qin J. Genes Dev. 2000;14:927–939. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stiff T, Reis C, Alderton GK, Woodbine L, O'Driscoll M, Jeggo PA. Embo J. 2005;24:199–208. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhong H, Bryson A, Eckersdorff M, Ferguson DO. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:2685–2693. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pichierri P, Rosselli F. Embo J. 2004;23:1178–1187. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cortez D. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1007–1012. doi: 10.1101/gad.1316905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee JH, Paull TT. Science. 2005;308:551–554. doi: 10.1126/science.1108297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carson CT, Schwartz RA, Stracker TH, Lilley CE, Lee DV, Weitzman MD. Embo J. 2003;22:6610–6620. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang H, Guan J, Perrault AR, Wang Y, Iliakis G. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8554–8563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Block WD, Yu Y, Lees-Miller SP. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:997–1005. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garcia-Muse T, Boulton SJ. Embo J. 2005;24:4345–4355. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsukuda T, Fleming AB, Nickoloff JA, Osley MA. Nature. 2005;438:379–383. doi: 10.1038/nature04148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jazayeri A, Falck J, Lukas C, Bartek J, Smith GC, Lukas J, Jackson SP. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;8:37–45. doi: 10.1038/ncb1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Costanzo V, Robertson K, Bibikova M, Kim E, Grieco D, Gottesman M, Carroll D, Gautier J. Mol Cell. 2001;8:137–147. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ziv Y, Bar-Shira A, Pecker I, Russell P, Jorgensen TJ, Tsarfati I, Shiloh Y. Oncogene. 1997;15:159–167. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.