1. Introduction

For patients infected with HIV, the benefits of successful antiretroviral therapy (ART) include decreased plasma HIV RNA viral load, increased peripheral blood CD4+ lymphocyte count, and evidence of immunologic recovery, which translate into decreased morbidity and mortality 1, 2. Moreover, patients with good virologic and immunologic response to ART can safely discontinue prophylaxis against many opportunistic infections 3–6. Despite these successes, incomplete immune restoration is increasingly reported in patients with undetectable viral loads and favorable CD4 counts 7–10. The clinical significance of incomplete immune restoration despite adequate CD4 T cell number is unknown as in vitro responses (typically measured by phenotyping of activated or naive T cells, delayed type hypersensitivity responses, lymphoproliferation, and responses to vaccines) do not predict the host response to opportunistic infections 7.

Several studies have shown that lower CD4+ T lymphocyte nadirs prior to starting ART are associated with diminished responses to vaccination and alterations in T cell phenotypes 11–13. This suggests that treatment strategies designed to delay or interrupt ART could have detrimental effects on functional immune restoration, particularly if patients show a significant decline in CD4 T cell counts during a treatment interruption. Although the mechanism by which a low CD4 T cell nadir causes long-term immune dysfunction is not fully understood, a recent study by Lange et al has shown that defects in CD28 expression may be important 12. It is also speculated that a critical threshold of memory T cells is needed to mount an effective response to recall antigens. The clinical significance of these persistent immunologic abnormalities is not entirely clear, but is likely to play a role in clinical decisions such as timing of vaccinations and initiation of anti-retroviral therapy.

In this work we hypothesized that failure of lymphocytes from HIV-infected subjects to respond to specific antigens in bulk assays was due to an absolute decrease in the number of CD4 cells in peripheral blood. Using an in vitro model, we demonstrate that when CD4 T cells from HIV infected patients are enriched from total blood lymphocytes the immune response to antigen is augmented. However, augmentation of this response is confined to HIV infected patients with relatively preserved CD4 T cell counts. Surprisingly, enriching for CD4 T cells had no effect on antigen responses in patients with low CD4 counts. These findings provide evidence that CD4 T cells in late stage HIV mount an ineffective immune response and suggest a “point of no return” after which immune restoration may be compromised.

2. Methods

2.1 Subjects

Ten HIV-positive patients (mean age 37 years; 9 men, 1 woman) served as the study population. Although 21 subjects were recruited for the study, only 10 had adequate responses to mitogen and enough CD4 cells after isolation to run proliferation assays on 2 recall antigens. All HIV-positive individuals had no recent illnesses or infections. None were taking antiretroviral therapy and all were viremic. The study population was enrolled before viral load measurements were used in clinical decision making and thus viral RNA data is incomplete. The mean CD4+ T-cell count of the population was 502 cells/μl (range 24–884 cells/μl). HIV-positive subjects were further divided into two groups based on peripheral blood CD4 counts: range 24–334 cells/μl (n = 5) and 484–884 cells/μl (n = 5). Nine healthy adult volunteers (mean age 30 years; 7 men, 2 women) were also studied. All subjects had reported previous vaccination to mumps and tetanus, but serologic confirmation of an antibody response was not available.

2.2 Isolation of cells and lymphoproliferation assays

After informed consent was obtained, peripheral blood was collected in heparinized syringes for isolation of peripheral blood T cells. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were separated by centrifugation through a Ficoll-Hypaque gradient. PBMCs were cultured on plastic for 2 h at 37°C to remove adherent monocytes. Nonadherent cells were subsequently passed over a nylon wool column to remove residual monocytes and/or macrophages and B cells. The resultant population consisted of > 95% lymphocytes. PBMCs were further purified into CD8+ and CD4+ subsets with the use of immunomagnetic beads adhering to manufacturer protocol (Dynal, Lake Success, NY). Greater than 95% of the isolated cell populations were viable by trypan blue exclusion. Adherent monocytes were incubated with 1 mM EDTA for 10 minutes on ice and then gently removed with a cell scraper. Lymphoproliferation assays were performed in triplicate using 96-well flat-bottomed microtiter plates. 1.5 × l04 monocytes/well and 1 × 105 total T cells or T cell subsets were incubated in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cultures were carried out in the absence and presence of either mumps or tetanus antigen for 6 days. Parallel three day cultures were carried out in the presence of the potent T cell mitogen PHA to assure the purified T cell populations were viable. 16 h before termination of culture, 1.0 kCi[3H]thymidine (5.0 Ci/mM; Amersham, Amersham, UK) was added. Cultures were collected with an automated cell harvester and counted in a liquid scintillation counter. The stimulation index (counts per minute in the presence of antigen divided by counts per minute in the absence of antigen) was determined for each experiment. In all experiments, if a response to mitogen was not detected, the data were discarded.

2.3 Clonal deletion assays

To generate a primary response in vitro, PBMC were prepared as above from healthy control volunteers. Monocytes were adhered for 2 hours in 5% FBS-RPMI to each well of 96 well plates and in T25 tissue culture flasks in parallel. Nonadherent cells were removed, processed into purified T cells as described above, and frozen for future use. Monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM) were generated from adherent monocytes by culture for 5 days in 20% FBS-RPMI supplemented with 10ng/ml M-CSF and antibiotics. MDM monolayers were exposed to HIV-1Ada-M at a TCID50 of 103 for 2 hours at 37°C as previously described 14. Culture plates were agitated every 20 minutes to facilitate infection. Cells were washed 3 times in RPMI and maintained in fresh M-CSF-containing media for 5 more days to establish infection. Autologous T cells were thawed and cultured at a ratio of MDM: T cell of 0.15:1 for 6 days in the presence of mumps, tetanus, or no antigen. After 6 days of co-culture, lymphoproliferation was measured in the 96 well plates as described above and the lymphocytes from the T25 flasks (which had been cultured under identical conditions) were collected for assessment of secondary T cell responses.

To measure the secondary T cell response, T cells that had been stimulated in flasks during the primary response were harvested and cultured for a second time with fresh MDM under the following conditions: HIV infected MDM with similar antigen to which the cells were primed, HIV infected MDM with different antigen to which the cells were primed, HIV uninfected MDM with similar antigen to which the cells were primed, and HIV uninfected MDM with different antigen to which the cells were primed. Proliferation was measured again at day 6 by tritiated thymidine incorporation.

In separate experiments, MDM were cultivated in 96 well plates, infected with HIV as above, and co-cultured with autologous T cells. To determine if inhibition of active viral replication affected subsequent T cell responses cultures were carried out in the presence and absence of 50 uM zidovudine. Proliferation was measured daily for 7 days and recorded as the primary response. Supernatants were assayed for p24 by ELISA (Coulter, sensitivity = 7.5 pg/ml) to ensure inhibition of viral replication in cultures containing zidovudine. On day 7, fresh media was added and the cells were rechallenged with antigen to determine the secondary response. Proliferation was again measured daily for 5 more days and p24 antigen again measured at the end of the experiment. In order to assure that cell viability was adequate and proliferative exhaustion was not occurring in long term culturing conditions, responses to PHA were measured in parallel and the data discarded if PHA response was absent.

2.4 Statistics

Data are shown as means ± standard error (SEM). Comparisons between group means was performed using the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test for nonparametric data. P values <0.05 were considered significant. Non-normal data were also analyzed, where appropriate, using a Friedman Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance on Ranks. Significant findings subsequently underwent pairwise post hoc analysis using Dunn’s Method. P values of <0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were done using SigmaStat Version 3.0.1a (Systat Software, Inc.).

3. Results

3.1 Proliferative responses to antigens can be augmented by CD4+ T cell isolation

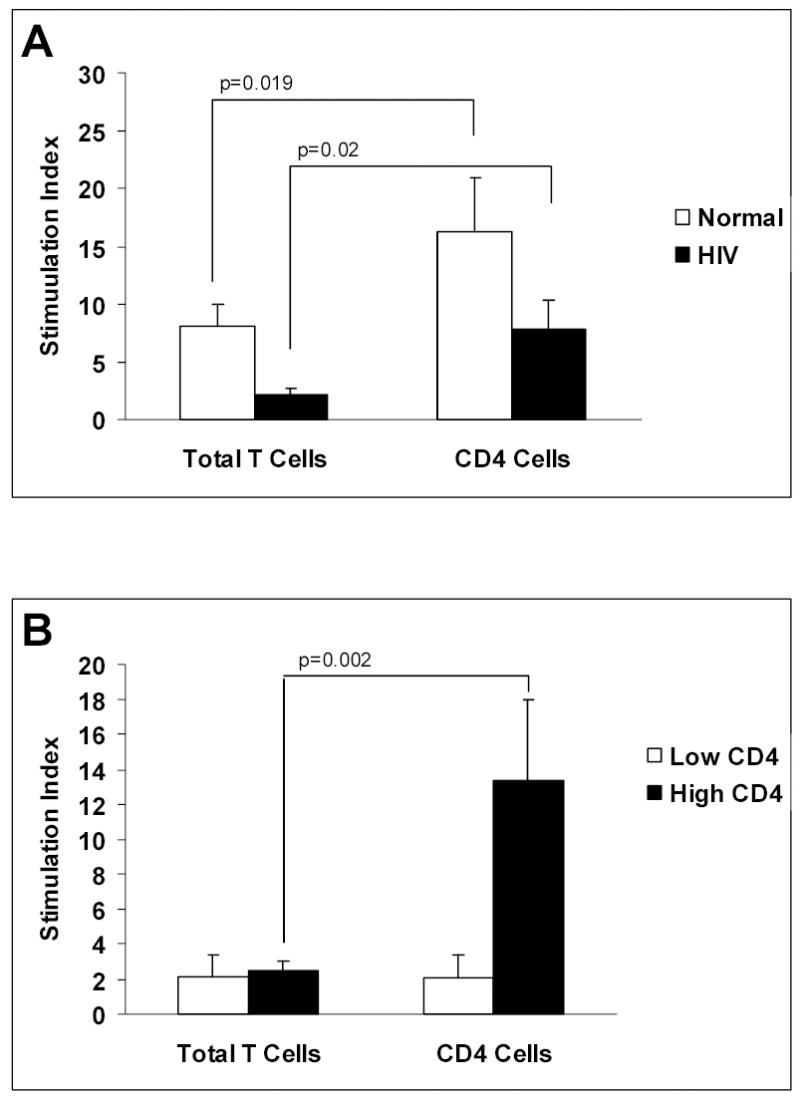

Although T cell responses to antigens are reported to be diminished in HIV infected subjects, it is unclear if this is simply due to diminished T cell numbers or qualitative defects in the remaining T cell pool. Monocytes obtained from HIV infected subjects and healthy controls were co-cultured with either total T cells or CD4+ enriched T cells at a ratio of 0.15:1 in the presence or absence of antigen. Figure 1 shows that proliferative responses can be elicited by antigen and augmented by enriching for CD4+ T cells. When total T cell proliferation is measured, healthy controls, in general, have a more robust response to antigenic stimuli. However, when CD4+ T cells are isolated and used as responder cells, both healthy controls and HIV infected subjects demonstrate a similar augmentation in proliferation compared to total T cells (figure 1A). This pattern was true for both mumps and tetanus (p < 0.1 for each antigen, not shown). The responses to mumps and tetanus are grouped in order to minimize the possibility that an absent proliferative response to either recall antigen is due to a poor immunologic response to previous vaccination. Interestingly, when HIV infected subjects are grouped as “low CD4” or “high CD4” based on peripheral blood CD4+ T cell counts, the ability to augment proliferation after CD4+ T cell isolation is lost in the “low” subject group (figure 1B). The ability to augment proliferative responses was noted only in subjects whose CD4+ T cell count was greater than 400 cells/ul. Thus, despite providing the same number of purified CD4+ T cells in culture conditions, the ability to respond to recall antigens is diminished in patients with lower peripheral blood CD4 T cell counts.

Figure 1.

Antigen-induced lymphoproliferation by purified total T cells and CD4 T cells in healthy controls and HIV-infected subjects. Monocytes and T cell populations were cultured at a ratio 0.15:1 for 6 days in the presence of mumps or tetanus. T cells from healthy controls (n=9) and HIV-infected subjects (n = 10) proliferated in response to antigen. T cell proliferation was significantly augmented when purified CD4 T cells were used as responders compared to total T cells (A). HIV Subjects with “low” CD4 counts (less than 400/ul, n=5) were unable to mount a response to either antigen even after enriching for CD4 T cells (B). In contrast, HIV subjects with “high” CD4 counts (n=5) were capable of robust proliferative responses (stimulation index comparable to healthy controls) when CD4 T cells were used as responders.

3.2 Antigen re-challenge causes “clonal deletion” of T cells

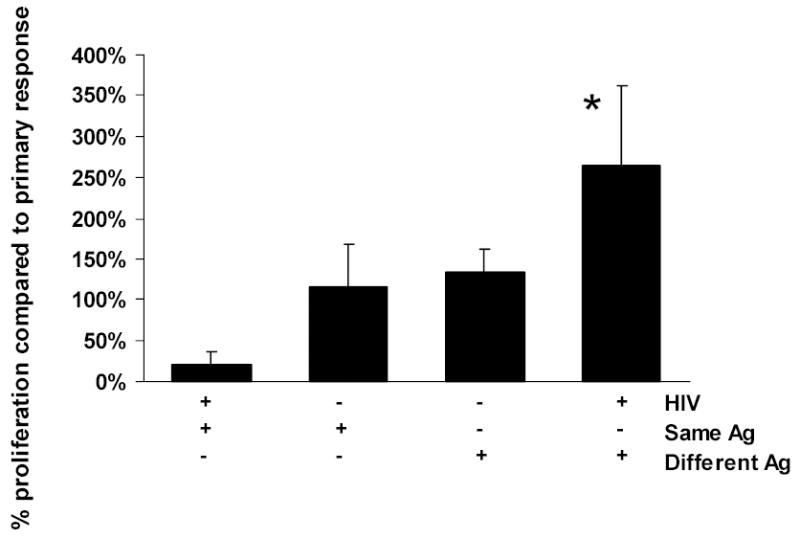

Because HIV-infected subjects with low CD4 T cell counts were unable to augment the response to mumps and tetanus even when CD4 T cell numbers were normalized, we speculated that T cells (likely memory T cells) reactive to common antigens were being selectively depleted. Specifically, we hypothesized that T cell responses to common antigens were being selectively lost during times of antigenic stimulation, leaving residual CD4 T cells responsive only to broadly conserved antigens remaining in patients with advanced HIV disease. To determine if deletion of antigen-specific T cells was a potential mechanism for the loss of T cell function, we cultured in vitro HIV-infected MDM with autologous uninfected T cells in bulk cultures under conditions identical to the lymphoproliferation experiments described above. T cells were harvested and recultured with HIV-infected or uninfected MDM in the presence of the same or different antigen. Figure 2 shows that when lymphocytes primed on HIV infected MDM are rechallenged with the same antigen, the proliferative response is markedly reduced to less than 20% of the baseline primary response (column 1). In contrast, when lymphocytes primed on HIV infected MDM are challenged with a different antigen (ie: primary response to tetanus, secondary response in the presence of mumps), proliferation is enhanced, indicating the ability of the T cell population to respond to antigen remains intact, even in the presence of HIV, as long as different recall antigens are used. Significantly, if the primary response is generated in the presence of normal, non HIV-monocytes (middle two bars, figure 2); the ability to respond to the same antigen is preserved. Thus, repeated exposure to a specific antigen in the presence of HIV-infected accessory cells results in loss of the ability to respond to that antigen.

Figure 2.

Secondary proliferative response to antigens measured as a percentage of the primary response. MDM (either HIV-infected or uninfected) and purified T cells were cultured at a ratio 0.15:1 for 6 days in the presence of mumps or tetanus. The resulting T cell populations were harvested and rechallenged with either the same or a different antigen. When lymphocytes stimulated by HIV-infected MDM are rechallenged with the same antigen, the secondary proliferative response is almost completely abolished. In contrast, when lymphocytes primed on HIV-infected MDM are challenged with a different antigen (ie: primary response to tetanus, secondary response in the presence of mumps), proliferation is enhanced, even in the presence of HIV (* p < 0.05 compared to same antigen, column 1). When a primary response is generated in the absence of HIV (middle two bars), the ability to respond to the same antigen is preserved, and frequently greater than the baseline primary response.

3.3 Antiviral treatment preserves lymphoproliferation upon antigen rechallenge

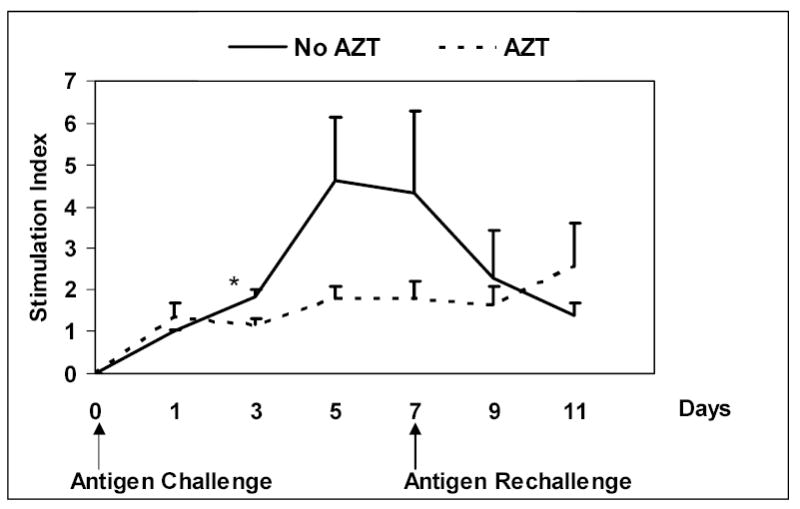

To further delineate if active viral infection was an important factor in the diminished T cell proliferation upon antigen rechallenge, T cell proliferation experiments were set up in parallel with and without zidovudine in the culture media. MDM were infected with HIV in vitro for these studies. Figure 3 shows that upon rechallenge with similar antigen on day 7, T cell proliferation declines over the subsequent 5 days. However, when zidovudine (AZT) is added to the culture media, the response to antigen challenge is preserved. Measurement of p24 concentrations in culture supernatants confirmed that zidovudine was inhibiting viral replication. These data suggest that uncontrolled HIV infection is responsible either for deletion of antigen-specific responding T cells or indirect suppression of proliferation in vitro. In the presence of zidovudine, although the response is diminished throughout the culturing period due to the inherent anti-proliferation effects of the drug, proliferative capacity is still preserved at day 11 suggesting loss of antigen-specific T cells is not occurring.

Figure 3.

Lymphoproliferative response to antigens in the presence of zidovudine. HIV-infected MDM and purified T cells were cultured at a ratio 0.15:1 in the presence of antigen and in the absence or presence of zidovudine. On day 7, cells were rechallenged with the same antigen. Lymphoproliferation was measured every 2–3 days. When zidovudine is present in the culture media, the secondary response to antigen challenge (and PHA) is preserved through day 11, though not statistically significant. In the absence of zidovudine, lymphoproliferative responses fall, even after rechallenge with the same antigen, suggesting a direct viral effect.

4. Discussion

The absolute CD4 T cell count is a valuable clinical marker for HIV disease progression and immune restoration. However, there is mounting evidence that 1) CD4 lymphopenia alone is not the sole mechanism of immune dysfunction, 2) A low CD4 T cell nadir is a marker for suboptimal immunologic recovery after starting ART, and 3) increases in CD4 T cells during ART do not predict successful restoration of immunologic responses to antigens 10, 11, 15. These findings have important implications for treatment strategies that delay or interrupt ART.

Our study is in agreement with these observations. We found that while antigen-specific responses were decreased in HIV-infected individuals, in some subjects enrichment for CD4 T cells was able to “restore” the proliferative response to recall antigens. However, in HIV-infected subjects with low CD4 counts, proliferative responses to recall antigen remained poor even after CD4 T cells were enriched to correct for low CD4 counts. In separate experiments, normal MDM infected with HIV in vitro were capable of eliciting a strong primary response to both mumps and tetanus antigen. However, when the responding T cell population was rechallenged with the same antigen the proliferative response was abolished. When rechallenged with a different antigen, lymphoproliferation was preserved. The loss of the secondary response to the same antigen was prevented by the addition of zidovudine to the media, suggesting a direct effect of viral infection on immune dysfunction. Taken together, these studies suggest T cell immune dysfunction cannot be solely ascribed to loss of CD4 T cell number and implicate deletion of antigen-specific T cells as an important mechanism of loss of T cell responses.

In the presence of ongoing antigenic challenges and uncontrolled HIV viremia, T cell death occurs. Although it is controversial whether cells are clonally deleted by direct infection or are lost through bystander activation and apoptosis, both mechanisms likely participate in vivo. Recently, in an acute SIV infection model, Mattapallil and colleagues demonstrated that up to 60% of memory T cells can be infected during the first few days after acquiring the virus. The implication of such a robust infection rate is that elimination of the majority of HIV-susceptible T cells is due to direct infection of these cells and not from “bystander effects” 16. Brenchley et al described similar findings of CD4+CCR5+ memory cell depletion in the GI tract that is most likely attributable to direct infection of these targets with subsequent cytolysis or CTL-specific killing 17. In this scenario, when memory cells are lost and fall below the threshold needed to respond to recall antigens, subsequent immunization will require naïve T cells to mount an immune response to newly recognized antigens. This also is problematic as HIV affects both naïve and memory T cell function during different stages of the disease 18, 19. Studies in our laboratory are ongoing to more rigorously determine the phenotype of HIV infected memory and naïve cell subsets that are most vulnerable to antigen induced proliferation and subsequent deletion.

Reports detailing the effect of immunization on the immune response and viral load are conflicting. Although vaccination may not induce effective cellular responses for many patients on ART 15, antibody responses may be better preserved 20. In addition, it is well-documented that antigen exposure via vaccination can cause immune activation and a transient increase in plasma viral load 21. Although perhaps clinically less important, this observation is in agreement with our study and suggests that repeated exposure of antigen in the absence of viral control can contribute to loss of antigen specific T cells.

Clinically, when to initiate ART remains controversial. Current guidelines suggest ART should be initiated in all symptomatic patients and in asymptomatic individuals when peripheral blood CD4 counts fall below 350/ul 22. It is intriguing that this value is close to the cutoff level we found where enriching for low CD4 counts no longer was able to restore antigen-induced lymphoproliferation. Our study is limited by small numbers of subjects and incomplete immunologic analysis prior to enrollment. In addition, we did not characterize these antigen-specific cells phenotypically due to relatively small numbers of cells in subjects with advanced disease. We could not assess the impact of viremia in this cohort. This is an important limitation as a recent study by Younes et al employed sophisticated assays to show that HIV-specific CD4+ T cells are unable to produce IL-2 in amounts capable of sustaining an effective memory cell response in viremic subjects compared to aviremic subjects23. Although copies of viral RNA were unable to be compared between the low and high CD4 groups, our results support the concept that CD4 T cell number does not adequately reflect qualitative defects in the remaining CD4 T cell pool.

In conclusion, HIV infection is characterized by progressive defects in cellular immunity that are partially reversible after initiation of antiretroviral therapy. Prior clinical experience and immunologic studies have demonstrated that waiting until CD4 counts are very low before starting ART is associated with poorer immune reconstitution. Our work, in agreement with other recent and elegant studies24 suggests this may be due to irreversible loss of antigen-specific T cells from the general CD4 T cell population. These results have implications for vaccine studies that enroll HIV-infected subjects with low CD4 counts and use proliferation to antigens as a readout. Additionally, this study indirectly supports current strategies to initiate HIV-specific antiretroviral therapy relatively early during the course of disease.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Yana Wang for her technical support. Supported by HL04545 to KS Knox and HL59834 to HL Twigg

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Autran B, Carcelain G, Li TS, et al. Positive effects of combined antiretroviral therapy on CD4+ T cell homeostasis and function in advanced HIV disease. Science. 1997;277(5322):112–6. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palella FJ, Jr, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(13):853–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Currier JS, Williams PL, Koletar SL, et al. Discontinuation of Mycobacterium avium complex prophylaxis in patients with antiretroviral therapy-induced increases in CD4+ cell count. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. AIDS Clinical Trials Group 362 Study Team Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(7):493–503. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-7-200010030-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furrer H, Egger M, Opravil M, et al. Discontinuation of primary prophylaxis against Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in HIV-1-infected adults treated with combination antiretroviral therapy. Swiss HIV Cohort Study. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(17):1301–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904293401701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldman M, Zackin R, Fichtenbaum CJ, et al. Safety of discontinuation of maintenance therapy for disseminated histoplasmosis after immunologic response to antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(10):1485–9. doi: 10.1086/420749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yangco BG, Von Bargen JC, Moorman AC, Holmberg SD. Discontinuation of chemoprophylaxis against Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients with HIV infection. HIV Outpatient Study (HOPS) Investigators. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(3):201–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-3-200002010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lederman HM, Williams PL, Wu JW, et al. Incomplete immune reconstitution after initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with severe CD4+ cell depletion. J Infect Dis. 2003;188(12):1794–803. doi: 10.1086/379900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pakker NG, Kroon ED, Roos MT, et al. Immune restoration does not invariably occur following long-term HIV-1 suppression during antiretroviral therapy. INCAS Study Group Aids. 1999;13(2):203–12. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199902040-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valdez H, Anthony D, Farukhi F, et al. Immune responses to hepatitis C and non-hepatitis C antigens in hepatitis C virus infected and HIV-1 coinfected patients. Aids. 2000;14(15):2239–46. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200010200-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valdez H, Connick E, Smith KY, et al. Limited immune restoration after 3 years’ suppression of HIV-1 replication in patients with moderately advanced disease. Aids. 2002;16(14):1859–66. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200209270-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Amico R, Yang Y, Mildvan D, et al. Lower CD4+ T lymphocyte nadirs may indicate limited immune reconstitution in HIV-1 infected individuals on potent antiretroviral therapy: analysis of immunophenotypic marker results of AACTG 5067. J Clin Immunol. 2005;25(2):106–15. doi: 10.1007/s10875-005-2816-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lange CG, Lederman MM, Medvik K, et al. Nadir CD4+ T-cell count and numbers of CD28+ CD4+ T-cells predict functional responses to immunizations in chronic HIV-1 infection. Aids. 2003;17(14):2015–23. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200309260-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lange CG, Valdez H, Medvik K, Asaad R, Lederman MM. CD4+ T-lymphocyte nadir and the effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on phenotypic and functional immune restoration in HIV-1 infection. Clin Immunol. 2002;102(2):154–61. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knox KS, Day RB, Wood KL, et al. Macrophages exposed to lymphotropic and monocytotropic HIV induce similar CTL responses despite differences in productive infection. Cell Immunol. 2004;229(2):130–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elrefaei M, McElroy MD, Preas CP, et al. Central memory CD4+ T cell responses in chronic HIV infection are not restored by antiretroviral therapy. J Immunol. 2004;173(3):2184–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mattapallil JJ, Douek DC, Hill B, Nishimura Y, Martin M, Roederer M. Massive infection and loss of memory CD4+ T cells in multiple tissues during acute SIV infection. Nature. 2005;434(7037):1093–7. doi: 10.1038/nature03501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brenchley JM, Schacker TW, Ruff LE, et al. CD4+ T cell depletion during all stages of HIV disease occurs predominantly in the gastrointestinal tract. J Exp Med. 2004;200(6):749–59. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Douek DC, McFarland RD, Keiser PH, et al. Changes in thymic function with age and during the treatment of HIV infection. Nature. 1998;396(6712):690–5. doi: 10.1038/25374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nobile M, Correa R, Borghans JA, et al. De novo T-cell generation in patients at different ages and stages of HIV-1 disease. Blood. 2004;104(2):470–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kroon FP, Rimmelzwaan GF, Roos MT, et al. Restored humoral immune response to influenza vaccination in HIV-infected adults treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy. Aids. 1998;12(17):F217–23. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199817000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gunthard HF, Wong JK, Spina CA, et al. Effect of influenza vaccination on viral replication and immune response in persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus receiving potent antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(2):522–31. doi: 10.1086/315260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammer SM. Clinical practice. Management of newly diagnosed HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(16):1702–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp051203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Younes SA, Yassine-Diab B, Dumont AR, Boulassel MR, Grossman Z, Routy JP, Sekaly RP. HIV-1 viremia prevents the establishment of interleukin 2-producing HIV-specific memory CD4+ T cells endowed with proliferative capacity. J Exp Med. 2003 Dec 15;198(12):1909–22. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lore K, Smed-Sorensen A, Vasudevan J, Mascola JR, Koup RA. Myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells transfer HIV-1 preferentially to antigen-specific CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2005;201(12):2023–33. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]