Abstract

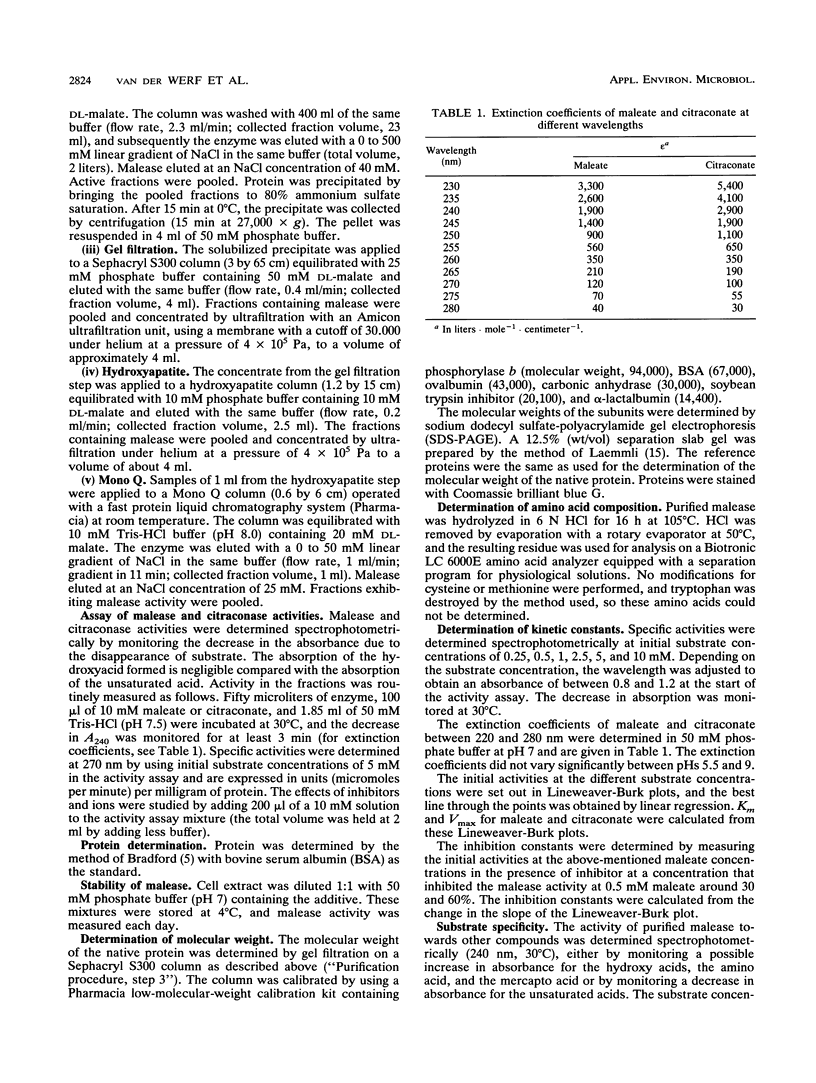

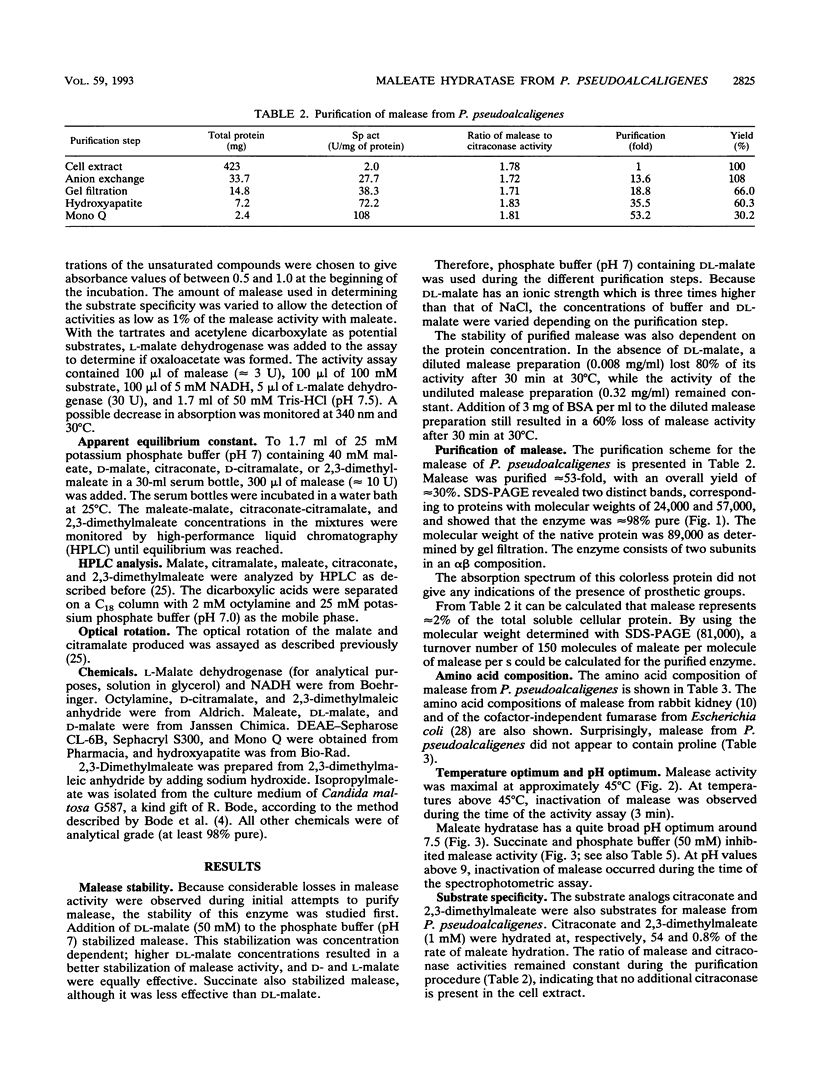

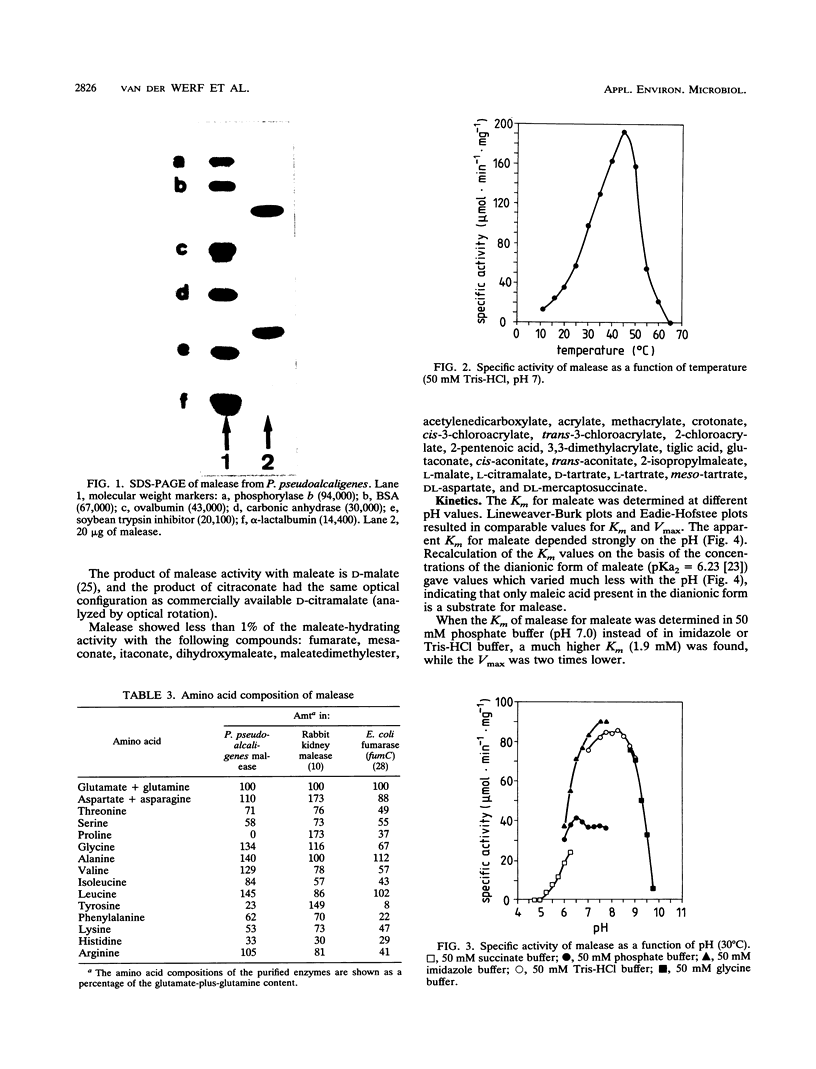

Maleate hydratase (malease) from Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes has been purified. The purified enzyme (98% pure) catalyzes the stereospecific addition of water to maleate and citraconate (2-methylmaleate), forming d-(+)-malate and d-(+)-citramalate, respectively. 2,3-Dimethylmaleate was also a substrate for malease. The stability of the enzyme was dependent on the protein concentration and the addition of dicarboxylic acids. The purified enzyme (89 kDa) consisted of two subunits (57 and 24 kDa). No cofactor was required for full activity of this colorless enzyme. Maximum enzyme activity was measured at pH 8 and 45°C. The Km for maleate was 0.35 mM, and that for citraconate was 0.20 mM. Thiol reagents, such as p-chloromercuribenzoate and iodoacetamide, and sodium dodecyl sulfate completely inhibited malease activity. Malease activity was competitively inhibited by d-malate (Ki = 0.63 mM) and d-citramalate (Ki = 0.083 mM) and by the substrate analog 2,2-dimethylsuccinate (Ki = 0.025 mM). The apparent equilibrium constants for the maleate, citraconate, and 2,3-dimethylmaleate hydration reactions were 2,050, 104, and 11.2, respectively.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bahnson B. J., Anderson V. E. Crotonase-catalyzed beta-elimination is concerted: a double isotope effect study. Biochemistry. 1991 Jun 18;30(24):5894–5906. doi: 10.1021/bi00238a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beinert H., Kennedy M. C. 19th Sir Hans Krebs lecture. Engineering of protein bound iron-sulfur clusters. A tool for the study of protein and cluster chemistry and mechanism of iron-sulfur enzymes. Eur J Biochem. 1989 Dec 8;186(1-2):5–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976 May 7;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer J. M. Yeast enolase: mechanism of activation by metal ions. CRC Crit Rev Biochem. 1981;11(3):209–254. doi: 10.3109/10409238109108702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten J. S., Morell H., Taggart J. V. Anion activation of maleate hydratase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1969 Jul 8;185(1):220–227. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(69)90296-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckel W., Miller S. L. Equilibrium constants of several reactions involved in the fermentation of glutamate. Eur J Biochem. 1987 May 4;164(3):565–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb11164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer J. L. Isolation and biochemical characterization of maleic-acid hydratase, an iron-requiring hydro-lyase. Eur J Biochem. 1985 Jul 1;150(1):145–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1985.tb09000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmans S., Smits J. P., van der Werf M. J., Volkering F., de Bont J. A. Metabolism of Styrene Oxide and 2-Phenylethanol in the Styrene-Degrading Xanthobacter Strain 124X. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989 Nov;55(11):2850–2855. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.11.2850-2855.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollmann-Koch A., Eggerer H. Nicotinic acid metabolism. Dimethylmaleate hydratase. Hoppe Seylers Z Physiol Chem. 1984 Aug;365(8):847–857. doi: 10.1515/bchm2.1984.365.2.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASSEY V. Studies on fumarase. 4. The effects of inhibitors on fumarase activity. Biochem J. 1953 Aug;55(1):172–177. doi: 10.1042/bj0550172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STERN J. R., DEL CAMPILLO A. Enzymes of fatty acid metabolism. II. Properties of crystalline crotonase. J Biol Chem. 1956 Feb;218(2):985–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian S. S., Rao M. R. Purification and properties of citraconase. J Biol Chem. 1968 May 10;243(9):2367–2372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda Y., Yumoto N., Tokushige M., Fukui K., Ohya-Nishiguchi H. Purification and characterization of two types of fumarase from Escherichia coli. J Biochem. 1991 May;109(5):728–733. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods S. A., Miles J. S., Roberts R. E., Guest J. R. Structural and functional relationships between fumarase and aspartase. Nucleotide sequences of the fumarase (fumC) and aspartase (aspA) genes of Escherichia coli K12. Biochem J. 1986 Jul 15;237(2):547–557. doi: 10.1042/bj2370547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Werf M. J., van den Tweel W. J., Hartmans S. Screening for microorganisms producing D-malate from maleate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992 Sep;58(9):2854–2860. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.9.2854-2860.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]