Abstract

Introduction

Adult group C beta-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis has a prevalence of approximately 5%. It can present with a broad spectrum of severity.

Case report

We report a 30-year-old woman who presented with severe Group C streptococcal pharyngitis.

Discussion

She presented with a 9-day history of progressive symptoms, including fever, sore throat, neck swelling, and recent onset of hoarseness. In the 9 days before the emergency room (ER) presentation, the patient had visited the ER twice complaining of a sore throat. At both visits, the physicians performed rapid antigen strep testing. Each time her test was negative and the physicians recommended symptomatic therapy. Her symptoms continued to worsen leading to her repeat presentation. At this time she had severe pharyngitis with markedly enlarged tonsils. Neck CT excluded peritonsillar abscess. Rapid strep testing was again negative, but her throat culture grew group C beta-hemolytic streptococcus.

Conclusion

This presentation illustrates the importance of a systematic approach to evaluating patients with negative rapid strep tests and worsening pharyngitis.

Key words: group C beta, streptococcal pharyngitis, tonsils

INTRODUCTION

Acute pharyngitis is one of the 5 most common reasons that adults visit a primary care physician for episodic care. Current guidelines assume that group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus is the only important treatable cause of episodic pharyngitis. These guidelines dissuade physicians from using antibiotics, unless a firm diagnosis of group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus can be made. Although these guidelines referred to the acute presentation of adult pharyngitis, occasionally patients present with worsening pharyngitis. We present a woman who presented with worsening pharyngitis and negative rapid antigen tests for group A pharyngitis. This presentation is rarely addressed in the guideline literature, yet this clinical presentation raises important diagnostic considerations for the General Internist.

CASE

A 30-year-old white woman presented to the emergency room (ER) complaining of sore throat, high fever, and neck swelling. She had first visited the ER on the third day of symptoms. On that visit, the patient complained of a sore throat, but denied fever or neck swelling. The ER examination showed neither exudates nor anterior cervical adenopathy. The ER physicians performed a rapid strep test, which was negative. She received conservative therapy (pain control but no antibiotics).

She returned 2 days later (day 5) with worsening symptoms. At that ER visit she had fever and severe throat pain. The ER physicians recorded tonsillar enlargement. They repeated the rapid strep test, which was again negative. They once again recommended symptomatic therapy and no antibiotics

Four days after that visit (day 9 of symptoms), she returned to the ER complaining of severe throat pain (10/10 intensity) accompanied by high fever and hoarseness. She denied shortness of breath, cough, dysphagia, or difficulty in breathing. On this visit she had a Centor score of 4 (tonsillar exudates, swollen tender anterior cervical adenopathy, fever history, and lack of cough).1 Previous ER records did not include complete data on these features.

The patient had taken only over-the-counter pain and cold medications over the previous week. The patient reported allergies to penicillin, cephalosporin, erythromycin, and sulfa drugs.

Socially, she lived alone. She denied being sexually active for 18 months (recent divorce). She did not smoke or use illicit drugs. She drank alcohol socially.

On physical examination, the vital signs showed a temperature of 101°F, heart rate of 101 beats/minute, a respiratory rate of 18/minute, and a blood pressure of 122/78 mmHg.

Generally, she appeared a well-developed white woman in obvious distress. She had bilateral tonsillar enlargement with prominent exudates and a nondisplaced uvula. She had mild enlargement of the anterior cervical nodes and moderate, diffuse anterior neck edema. She had diffuse, moderate tenderness over her entire anterior neck. She had no stridor but had hoarseness. She had normal bilateral breath sounds with no wheezes and no crackles. Cardiac examination showed normal S1 and S2 heart sounds regular in rate and rhythm with no murmurs, rubs, or gallops. Peripheral pulses were easily palpable. Her abdomen was soft and nondistended and she had normal bowel sounds. She had no skin lesions. Neurological examination revealed normal higher mental function and she had no deficits of strength or reflexes.

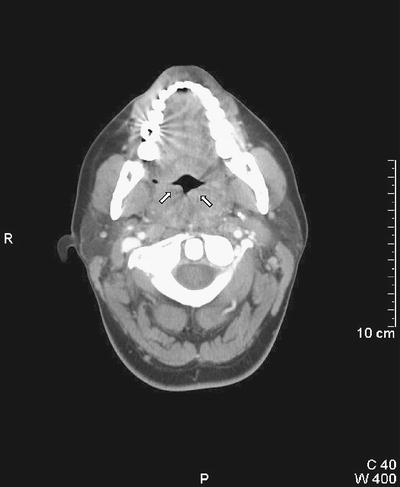

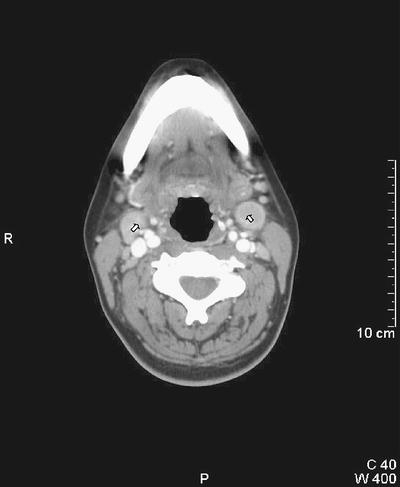

Initial laboratory findings of the most recent ER visit showed WBC of 9.28 cells/mm3 (N 82.5%, L 9.5%, M 7.4%, E 0.3%, and B 0.4%). Both the rapid streptococcal antigen test and monospot test were negative. A CT scan of the neck showed bilateral thickening of the tonsil region with no definite abscess (Figs. 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

CT scan of the neck: arrows (↑) show enlarged palatine tonsils kissing each other with no signs of peritonsillar abscess.

Figure 2.

CT scan of the neck: arrows (↑) show enlarged jugulodigastric lymph nodes.

After obtaining throat cultures for routine bacterial pathogens and Neisseria gonorrhea and Chlamydia, we started antibiotic therapy with intravenous clindamycin, and added intravenous methylprednisolone. A rapid influenza test, cytomegalovirus IgM titers, and Epstein–Barr virus IgM titers were all negative. Her HIV antibody test was negative, as was a culture specific for Neisseria gonorrhea.

The patient’s antistreptolysin O (ASO) screen came back positive with a titer of 400 IU/mL on the second day of admission. Subsequently, her throat culture grew beta-hemolytic group C Streptococcus. The patient made a full recovery after a 7-day course of clindamycin and oral steroids.

DISCUSSION

The recommended diagnostic approach to the adult pharyngitis patient focuses on the possibility of group A beta-hemolytic streptococci. Current guidelines consider group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus as the sole reason for antibiotic treatment.2,3 These guidelines focus on limiting the use of antibiotics in probable viral pharyngitis. Although these two most recent guidelines have slight disagreements, both would agree with withholding antibiotic treatment of rapid test–negative patients.

These guidelines focus on the initial acute presentation of adult pharyngitis. Our patient represents a different diagnostic dilemma. What etiologies should we consider in a rapid test–negative adult patient with worsening pharyngitis?

We must recognize that rapid antigen detection tests have imperfect sensitivity. Most studies report sensitivity between 80% and 90%.4 Thus, some patients with negative rapid tests and worsening symptoms will still have group A beta–hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis.

We must consider at least 5 other important possibilities in patients who present with a negative rapid strep test and worsening pharyngitis: infectious mononucleosis, acute HIV infection, nongroup A beta–hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis (especially group C or group G beta–hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis), peritonsillar abscess, and Lemierre’s syndrome (Fusobacterium necrophorum). Patients with each of these diagnoses will have negative rapid strep tests and possibly worsen over the first week of symptoms.

Our patient had appropriate testing for infectious mononucleosis. Her negative monospot test made that diagnosis very unlikely. Although infectious mononucleosis can present with persistent symptoms, her worsening throat symptoms made this diagnosis less likely.

She admitted no risk factors for acute HIV infection, and had a negative HIV antibody test. Acute HIV infection presents much like infectious mononucleosis. Although her presentation was not typical for acute HIV, we still considered that possibility.

Because of her severe presentation, we performed a CT scan of her throat. This scan showed severe tonsillitis, but did not show evidence of either peritonsillar abscess or Lemierre’s syndrome.5

The throat culture made the diagnosis. Beta-hemolytic group C Streptococcus is a less common cause of acute pharyngitis but has both similar microbiology and presentation to group A beta-hemolytic streptococci. Both cause isolated exudative or common source epidemic pharyngitis and cellulitis, which are indistinguishable clinically. Some strains of group C Streptococcus also contain fibrinolysins and streptolysins, which can stimulate ASO titers.

Several studies have demonstrated that group C streptococci are a relatively common cause of acute pharyngitis among college students and among young adults seeking care in an ER.6,7 The diagnosis of group C Streptococcus should be considered in a patient with negative rapid antigen detection test and a worsening clinical course. Although not as common as group C streptococcal pharyngitis, group G can have a similar presentation.8

Although a group C streptococcus has a prevalence of less than 5% in adult pharyngitis patients,9 it can cause severe pharyngitis. This patient demonstrated an extreme presentation of progressive group C pharyngitis.

Current strategies for screening adult pharyngitis patients will miss these unusual causes of severe pharyngitis. When the patient presents with worsening pharyngitis, then we must consider an expanded differential diagnosis. We would suggest that worsening pharyngitis patients should have a throat culture (not a second rapid test) to test for both group A and nongroup A beta-hemolytic streptococci. If the physical examination suggests the possibility of either abscess or suppurative thrombophlebitis, then one should obtain a CT of the throat. Finally, one must consider the possibility of infectious mononucleosis10,11 and do appropriate testing.

Footnotes

Potential Financial Conflicts of Interest:

None disclosed.

References

- 1.Centor R, Witherspoon J, Dalton H, Brody C, Link K. The Diagnosis of Strep Throat in Adults in the Emergency Room. Med Dec Making. 1981;1(3):239–46. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Bisno A, Gerber M, Gwaltney J. Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:113–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Gonzales R, Bartlett J, Besser R. Principles of Appropriate Use for Treatment of Acute Respiratory Tract Infections in Adults: Background, Specific Aims, and Methods. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:479–86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Gerber M, Shulman S. Rapid Diagnosis of Pharyngitis Caused by Group A Streptococci. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:571–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Ochoa R, Goldstein J, Rubin R. Clinicopathological Conference: Lemierre’s Syndrome. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:152–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Meier F, Centor R, Graham L, Dalton H. Clinical and Microbiological Evidence for Endemic Pharyngitis Among Adults due to Group C Streptococci. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:825–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Turner J, Hayden F, Lobo M, Ramirez C, Murren D. Epidemiologic Evidence for Lancefield Group C Beta-hemolytic Streptococci as a Cause of Exudative Pharyngitis in College Students. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Lindboek M, Hoiby E, Lermark G, Steinsholt I, Hjortdahl P. Clinical Symptoms and Signs in Sore Throat Patients with Large Colony Variant Beta-haemolytic Streptococci Groups C or G Versus Group A. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55:615–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Zwart S, Sachs A, Ruijs G, Gubbels J, Hoes A, Melker R. Penicillin for acute sore throat: randomized double blind trial of seven days versus three days treatment or placebo in adults. Br Med J. 2000;320:150–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Johnsen T, Katholm M, Stangerup S. Otolaryngological Complications in Infectious Mononucleosis. Laryngol Otol. 1984;98(10):999–1001. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Stevenson D, Webster G, Stewart I. Acute Tonsillectomy in the Management of Infectious Mononucleosis. J Laryngol Otol. 1992;106(11):989–91. [DOI] [PubMed]