Abstract

Background

Despite recommendations, osteoporosis screening rates among women aged 65 years and older remain low. We present results from a clustered, randomized trial evaluating patient mailed reminders, alone and in combination with physician prompts, to improve osteoporosis screening and treatment.

Methods

Primary care clinics (n = 15) were randomized to usual care, mailed reminders alone, or mailed reminders with physician prompts. Study patients were females aged 65–89 years (N = 10,354). Using automated clinical and pharmacy data, information was collected on bone mineral density testing, pharmacy dispensings, and other patient characteristics. Unadjusted/adjusted differences in testing and treatment were assessed using generalized estimating equation approaches.

Results

Osteoporosis screening rates were 10.8% in usual care, 24.1% in mailed reminder, and 28.9% in mailed reminder with physician prompt. Results adjusted for differences at baseline indicated that mailed reminders significantly improved testing rates compared to usual care, and that the addition of prompts further improved testing. This effect increased with patient age. Treatment rates were 5.2% in usual care, 8.4% in mailed reminders, and 9.1% in mailed reminders with prompt. No significant differences were found in treatment rates between those receiving mailed reminders alone or in combination with physician prompts. However, women receiving usual care were significantly less likely to be treated.

Conclusions

The use of mailed reminders, either alone or with physician prompts, can significantly improve osteoporosis screening and treatment rates among insured primary care patients (Clinical Trials.gov number NCT00139425).

KEY WORDS: mailed reminders, osteoporosis, physician prompts, screening, bone mineral density testing

BACKGROUND

Osteoporosis screening for women 65 years and older is recommended in evidence-based guidelines.1–3 Yet, evidence exists that less than a third of at-risk women receive bone mineral density (BMD) testing.4 Thus, a large number of women are at risk of not receiving needed and known effective therapy, thereby unnecessarily increasing the burden of osteoporosis and its consequences.5

Ensuring the receipt of recommended preventive care is one of the many public health challenges of the 21st century.6 Patient mailed reminders and medical record prompts represent cues to action that have been shown to be effective in improving preventive health service use.7–13 Such approaches are advantageous as they enable systematic targeting of patient populations at minimal costs.14 We present results from a randomized trial evaluating the extent to which patient mailed reminders, alone and in combination with physician prompts, improved osteoporosis screening and treatment rates.

METHODS

Research Design

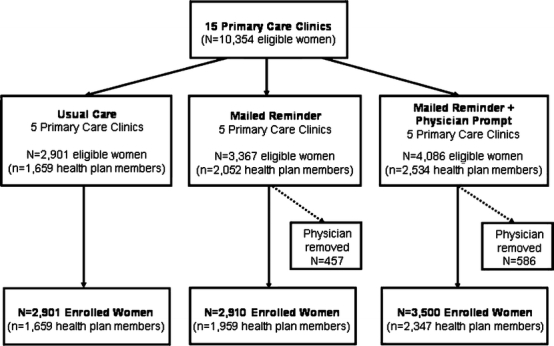

We used a cluster randomized design in which primary care clinics, stratified by size and on-site availability of BMD testing, were randomized to three arms: usual care, patient-mailed reminders, and patient-mailed reminders in combination with a physician prompt (Fig. 1). Within stratum, clinics were allocated to the three arms using a random numbers table. Patients receiving care from clinics randomized to the two active intervention arms were observed for one year beginning on the date their initial patient reminder was sent. Usual care patients were randomly assigned a pseudo mailing date.

Figure 1.

Evaluation eligible and program enrolled clinics and patients by study arm.

The study was funded by Merck & Co., Inc. The protocol was approved by the participating medical group’s Internal Review Board (IRB).

Study Setting and Patient Eligibility

Study patients were selected from among those receiving care from a large, multispecialty, salaried group practice in southeast Michigan. At the time of the study, the group staffed 23 ambulatory care clinics in the Detroit metropolitan area. Fifteen suburban clinics staffed by 123 primary care physicians were randomized. Patients available for study inclusion included both those with insurance coverage via an affiliated health plan and those with other types of coverage.

Eligible patients included women aged 65–89 years of age on 3/31/2003 with a visit between 4/1/2001 and 3/31/2003 to a primary care physician (i.e., general internist or family practitioner). Women were aligned to the primary care physician they saw most often during this time. A visit was required to enable the patient reminder letter to be sent under the signature of the patients’ physician. We targeted women aged 65–89 years as they reflect patients for whom osteoporosis screening most likely was appropriate.

Women with evidence of a previous osteoporosis diagnosis, BMD screening, or dispensing for an osteoporosis-specific medication were excluded from the evaluation. Physicians in the 2 active intervention arms were given the option of removing any of their patients for whom they felt it would be inappropriate to receive a mailing. Patients removed by a physician were excluded from receiving the interventions, but not from the evaluation (i.e., the evaluation uses an intent-to-treat design).

The Patient-Mailed Reminder and Physician Prompt

Initial and 1-month follow-up patient mailings were sent to women in the active intervention arms. A third, follow-up mailing was sent to only those women in the active arms who received a screening result reflecting a need to consider osteoporosis treatment (i.e., hip or spine t ≤ −2.0). Each mailing included two items: a letter from the individual’s physician and educational information. Initial letters provided background information regarding osteoporosis, patient risk factors, and emphasized the importance of screening. They specified how to schedule a BMD test and served as a referral form for testing. The accompanying educational material, while similar in content across the two mailings, used different formats. Material in the initial mailing focused on increasing patient’s perceived susceptibility and addressed common barriers to BMD testing. The 1-month follow-up included a brochure on osteoporosis risk, understanding your t score, and protecting yourself against osteoporosis. Postscreen follow-up mailings, sent to the subset of women receiving a BMD test result suggestive of the need for follow up (i.e., hip or spine t ≤ −2.0), were sent 3–6 months after testing and recommended scheduling a visit with their doctor to discuss BMD screening results. The accompanying educational material covered osteoporosis injury prevention and tips for keeping bones strong. Initial mailings were sent in biweekly batches beginning August 4, 2003 and were completed by December 5, 2003.

The physician prompt consisted of 2 components. First, a prompt appeared in the electronic medical record (EMR) of all eligible women receiving care in a clinic randomized to receive the physician prompt. The second component was a biweekly mailing to physicians that was sent to coincide with the 3–6 month postscreen patient mailing. The letter listed the physician’s patients who received a t score ≤ −2.0 and indicated that osteoporosis treatment should be considered.

At the time of the BMD test, all patients, regardless of study arm, received a printed copy of their test results along with a standardized written recommendation for follow up based on t scores.

Primary Outcomes and Data Sources

The primary outcome of interest was the use of BMD testing. Bone mineral density testing use was determined using CPT-4 codes. Testing use was compiled for the 12-month period after the date of the first mailing for intervention patients and the corresponding pseudo mailing date for usual care patients. We hypothesized that women who received mailed reminders alone would be more likely to receive a BMD test compared to women receiving usual care, and that women who received mailed reminders in combination with physician prompts would be more likely than those women in either of the 2 other study arms to receive BMD testing.

A secondary outcome of interest was the dispensing of an osteoporosis medication. As pharmacy data were not available for women with health insurance coverage from a source other than the affiliated health plan, treatment use was evaluated among the subset of women enrolled in the affiliated health plan. For these women, health plan pharmacy claims data were used to compile information on dispensings for raloxifene, alendronate, risedronate, calcitonin (salmon), teriparatide, and ibandronate. For this outcome, we hypothesized that osteoporosis treatment dispensings would be more likely among women who received mailed reminders in combination with physician prompts compared to women in either of the other 2 study arms.

We also used automated clinical/administrative databases to compile information on other patient characteristics that might influence either their osteoporosis risk or their likelihood of treatment. Administrative records were used to compile demographic information (i.e., age, race, and marital status) as well as enrollment in the affiliated health plan. Automated encounter data were used to capture information on primary care visits, inpatient hospital admissions, associated diagnostic codes (i.e., ICD-9-CM codes), and procedure use (i.e., CPT-4 codes). Using these latter data, we constructed variables reflective of the number of primary care visits, and whether or not the woman was admitted to the hospital, received a mammogram, or had evidence of a fracture in the 1-year period preceding their mailing/pseudo mailing date. Finally, for women enrolled in the affiliated health plan, we used pharmacy claims data to capture dispensings for hormone replacement therapy and steroids during the same 12-month period.

Statistical Methods

The unit of analysis for all statistical analyses was the patient. Differences in patient baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics by study arm were evaluated using analysis of variance or chi-square tests. Differences in BMD testing and treatment rates were assessed using logistic regression. In all instances, generalizing estimating equation (GEE) approaches were used to account for the non-independence of patients receiving their care from the same primary care physician and within the same primary care clinic. Adjusted comparisons were conducted controlling for patient baseline age, race, marital status, fracture history, health plan enrollment, and hospital, primary care, and mammography use. When equations are limited to only those women enrolled in the affiliated health plan, we also are able to control for hormone replacement therapy and steroid use. Pairwise interactions between study arm and the other significant included variables were assessed. Only statistically significant pairwise interactions were retained.

For the primary outcome of interest (BMD testing), a priori we estimated power using 75 providers evenly distributed across the 3 study arms, each with an assumed 140 aligned patients, and an interclass correlation coefficient of 0.01. This resulted in an expected power (at an adjusted alpha level of 0.017) of 80% or higher for pairwise comparisons involving usual care, and an expected power of 74% for the pairwise comparison between mailed reminders alone and mailed reminders in combination with physician prompts.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Figure 1 illustrates the number of eligible women by treatment arm and insurance coverage. Evaluation eligible women (N = 10,354) included 2,901 women receiving care in usual care clinics, 3,367 women receiving care in mailed reminder clinics, and 4,086 women receiving care in mailed reminder combined with physician prompt clinics. Table 1 compares the baseline characteristics of eligible women by study arm. Although statistically significant baseline differences were found for most of the patient characteristics assessed, only a handful of meaningful differences existed. Women in the patient mailed reminder arm were less likely to be African American (11.9% vs 16.9% in usual care and 18.5% in the combined patient reminder/physician prompt arm). We also observed variation in health plan enrollment, ranging from a low of 57.2% among usual care patients to a high of 62.0% among those in the combined patient reminder/physician prompt arm. Finally, women in the combined intervention arm were substantively more likely to have received mammography screening (34.8%) compared to those in the other 2 arms (30.4% in the patient reminder arm and 29.4% in the usual care arm).

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics among All Eligible Participants by Study Arm

| Usual Care (n = 2,901) | Patient Mailed Reminder (n = 3,367) | Patient Mailed Reminder and Physician Prompt (n = 4,086) | p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic Characteristics | ||||

| Mean Age (SD) | 75.4 ± 6.4 | 75.8 ± 6.3 | 75.6 ± 6.3 | < 0.01 |

| Percent Black | 16.9 | 11.9 | 18.5 | < 0.01 |

| Percent Currently Married | 48.2 | 49.2 | 54.2 | < 0.01 |

| Percent Enrolled in Health Plan | 57.2 | 60.9 | 62.0 | < 0.01 |

| Clinical Characteristics | ||||

| Mean Primary Care Visits (SD) | 4.7 ± 3.7 | 4.7 ± 4.0 | 4.4 ± 3.6 | < 0.01 |

| Mean Hospital Admits (SD) | 0.2 ± 0.6 | 0.2 ± 0.7 | 0.2 ± 0.6 | 0.06 |

| Percent with Mammography | 29.4 | 30.4 | 34.8 | < 0.01 |

| Percent with History of Fracture | 3.6 | 4.0 | 3.6 | 0.64 |

*p value based on ANOVA for means and chi-square test for proportions.

We also compared the characteristics of patients enrolled in the health plan versus those otherwise insured. Health plan patients were significantly younger (75.0 vs 76.6 years of age), had significantly more primary care visits (5.1 vs 3.8), and were significantly more likely to have had a mammogram (37.5 vs 23.4%), a fracture (4.5 vs 2.6%), or depression diagnosis (4.3 vs 2.1%).

Osteoporosis Screening Use

Unadjusted postperiod screening rates were 10.8% in the usual care arm, 21.4% in the mailed reminder arm, and 28.9% in the mailed reminder in combination with physician prompt arm (p < 0.001). Among those tested, the rate of abnormal findings (i.e., hip or spine t score ≤ −2.0) did not differ significantly by study arm (p = 0.104), and was 16.2% in usual care, 17.8% in the mailed reminder arm, and 13.7% in the mailed reminder in combination with physician prompt arm.

Table 2 presents the adjusted postperiod BMD testing rates. Because we found a statistically significant interaction between study arm and participant age, the table presents adjusted rates by study arm and three illustrative ages: 65, 75, and 85 years. As illustrated in the table, the interventions significantly improved the use of BMD testing, although differentially by age, with improvements increasing with age.

Table 2.

Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) Adjusted Bone Mineral Density Testing (BMD) Rates (95% Confidence Intervals) among All Eligible Participants (n = 9,659) and Osteoporosis Treatment Rates (95% Confidence Intervals) among All Eligible Health Plan Participants with a Bone Mineral Density (BMD) Test (n = 5,877)

| Usual Care | Patient Mailed Reminder | Patient Mailed Reminder and Physician Prompt | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screening | |||

| Age 65 | 17.0 (13.8, 20.9) | 23.2 (20.6, 25.9) | 30.3 (27.8, 32.9) |

| Age 75 | 10.1 (8.0, 12.6) | 18.7 (16.5,21.0) | 27.0 (24.7, 29.4) |

| Age 85 | 5.8 (4.5, 7.3) | 14.8 (13.1, 16.8) | 23.9 (21.8, 26.2) |

| Treatment | 2.3 (1.6, 3.3) | 4.0 (2.8, 5.7) | 3.9 (3.0, 5.1) |

With the exception of prior fracture and race, other patient factors controlled in the model were also significantly (p < 0.05) associated with BMD screening use. BMD screening use was significantly greater among married patients (OR = 1.21, 95% CI 1.08–1.35), those enrolled in the health plan (OR = 1.85, 95% CI 1.63–2.10), and those with a history of mammography use (OR = 2.17, 95% CI 1.97–2.39). We also found BMD screening use to increase with increasing primary care visit frequency (OR = 1.19, 95% CI 1.14–1.24) and to decrease with the number of hospital admissions (OR = 0.74, 95% CI 0.68–0.82). Appendix Table 3 presents full model results.

Table 3.

Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) Parameter Estimates for Bone Mineral Density (BMD) Testing among All Eligible Participants (n = 9,659)

| Estimated Beta | Standard Error | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mailed Reminder (vs. Usual Care) | −1.7592 | 0.9636 | 0.07 |

| Mailed Reminder + Physician Prompt (vs. Usual Care) | −2.1222 | 0.8957 | 0.02 |

| Age | −0.0604 | 0.0108 | < 0.01 |

| Age × Mailed Reminder | 0.0329 | 0.0130 | 0.01 |

| Age × Mailed Reminder + Physician Prompt | 0.0442 | 0.0122 | < 0.01 |

| Black | −0.0179 | 0.0767 | 0.82 |

| Currently Married | 0.1896 | 0.0562 | < 0.01 |

| Primary Care Visits* | 0.0576 | 0.0075 | < 0.01 |

| Hospital Admits** | −0.2952 | 0.0469 | < 0.01 |

| Mammography Use | 0.7734 | 0.0489 | < 0.01 |

| Fracture History | 0.0476 | 0.1431 | 0.74 |

| Health Plan Enrollment | 0.6144 | 0.0647 | < 0.01 |

| Intercept | 1.4175 | 0.7916 | 0.07 |

*Beta reflects visit change of 3.

**Beta reflects each additional admission.

Osteoporosis Treatment

Unadjusted osteoporosis treatment rates among eligible women with a BMD test were 5.2% in the usual care arm, 8.4% in the mailed reminder arm, and 9.1% in the mailed reminder in combination with physician prompt arm. As illustrated in Table 2, regression adjusted results also indicated that women receiving their care from one of the 2 active intervention arms were significantly more likely to have been dispensed an osteoporosis medication than those receiving usual care. We found no significant difference in the likelihood of treatment between those women receiving the mailed reminder and those receiving it in combination with the physician prompt. The only other factor significantly associated with treatment was marital status. Appendix Table 4 presents full model results.

Table 4.

Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) Parameter Estimates for Osteoporosis Treatment among All Eligible Health Plan Participants with a Bone Mineral Density (BMD) Test (n = 5,877)

| Estimated Beta | Standard Error | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mailed reminder (vs usual care) | 0.5875 | 0.2758 | 0.03 |

| Mailed reminder + physician prompt (vs usual care) | 0.5595 | 0.2411 | 0.02 |

| Age | 0.0160 | 0.0138 | 0.24 |

| Black | 0.3863 | 0.2107 | 0.07 |

| Currently married | 0.6288 | 0.1732 | < 0.01 |

| Primary care visits* | 0.0344 | 0.0207 | 0.10 |

| Hospital admits** | −0.1487 | 0.0974 | 0.13 |

| Fracture history | 0.5770 | 0.3020 | 0.06 |

| Steroids | 0.2737 | 0.2354 | 0.24 |

| Hormone replacement therapy | −0.0279 | 0.2360 | 0.91 |

| Intercept | −5.5266 | 1.1197 | < 0.01 |

*Beta reflects visit change of 3.

**Beta reflects each additional admission.

DISCUSSION

The use of mailed patient reminders appears to hold promise for improving osteoporosis screening and treatment rates. Our findings indicate that the use of mailed reminders significantly increased osteoporosis screening rates among insured women. Furthermore, such reminders worked particularly well among women of advanced age: Compared to those receiving usual care, we found 85-year-old women to be 2.5 times more likely to receive BMD testing when receiving mailed reminders, whereas those aged 75 were just under twice as likely. The addition of a physician prompt lead to further improvements in screening use, with women aged 85 being almost five times as likely to receive testing and those aged 75 just over 3 times as likely compared to usual care. Thus, whereas we found mailed patient reminders, alone or in combination with physician prompts, to improve screening rates, we found this effect increased with patient age—or among exactly those women at the most risk.

An estimated 8 million women aged 50 and over suffer from osteoporosis in the United States alone,5,15 with an estimated 50% of postmenopausal women suffering from an osteoporosis-related fracture during their lifetime.16–18 Such fractures have a significant impact on health status,19,20 and the US healthcare system.21 Despite such facts, BMD screening rates for women at risk for osteoporosis are low. Even among women with a recent fracture, BMD testing rates have been found to range from a low of 1% to a high of only 32%.4,14,22 Estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) further reveal that whereas 11% of women report having osteoporosis, 26% actually test positive for the disease.5 Recent reviews only add to concerns, highlighting the gap between those with disease and those receiving treatment23 Such findings are particularly troubling, as estimates of the number needed to screen to prevent an osteoporotic fracture are reasonable (i.e., 248 for vertebral fracture and 741 for hip fracture).24

The need for a more effective approach to osteoporosis screening is clear. Yet, only 3 previously published efforts have evaluated osteoporosis screening programs using a randomized design,25–27 and findings from these efforts have been mixed. Wroe and colleagues found positively stated patient messages (vs negatively stated ones) to improve BMD screening rates.26 Stock and colleagues found the use of long (vs short) reports provided to physicians to also improve BMD screening use.27 However, Solomon and colleagues found patient mailed reminders to have no effect on self-reported BMD screening use among Medicare enrollees.25 Rigorous evaluations of efforts to improve osteoporosis treatment rates are similarly uncommon and have likewise produced mixed results.23,28–30

Whereas the use of patient mailed reminders alone led to increases in BMD testing rates, the addition of physician prompts further improved testing rates, thereby illustrating the potential of reminders and prompts combined to improve osteoporosis screening rates. The interventions evaluated here also led to significant, albeit small, improvements in treatment rates among those tested. We, however, did not find an additional advantage of physician prompts for treatment. Treatment gaps and the challenges in closing them previously have been documented.31

Despite our findings that the use of mailed reminders, either alone or in combination with physician prompts, can improve osteoporosis screening rates, we found screening rates—even among those women receiving both interventions combined—remained far below optimal among this insured population. Among women receiving patient-mailed reminders in combination with physician prompts, we found under a third of women were tested and this dropped to just over 10 percent among those patients in usual care. Thus, the need to develop and evaluate other programs, either alone or in combination with reminders and prompts, to improve osteoporosis screening and treatment among at risk populations remains critical.

Care should be taken when generalizing these findings to other populations. Our findings are among insured women receiving primary care within 2 suburban regions of an integrated delivery system. Although this population is similar in demographics to the larger population in southeast Michigan, they may differ from those receiving care in urban areas, those residing in other geographic areas, or in other unmeasured ways. Of particular note is the need to be careful generalizing our findings to non-insured women. Furthermore, the integrated delivery system may afford advantages and opportunities (such as an electronic medical record and centralized appointment scheduling) that might limit the feasibility of implementing such programs in other settings. Also of note is that at the time of the study, prescription drug coverage was not commonplace among the elderly. How the new Medicare benefit will impact osteoporosis treatment in general is not known. Finally, despite our ability to control for a number of patient characteristics, patients could have varied in unmeasured ways (such as health and functional status, health behavior, or income/education) among the 3 study arms.

As computer technology becomes more available within health care settings, many primary care practices will be able to use clinical informatic tools to monitor the receipt of routine services and facilitate the implementation of automated reminder and prompt systems. The use of such patient-mailed reminders and in-office prompts previously has been associated with improved screening performance.7–13 This study demonstrates the benefit of these tools—particularly when used in combination—to improve BMD screening rates.

Acknowledgments

Potential Financial Conflict of Interest Dr. Weiss and Dr. Chen are employees of Merck & Co.

Appendix

Footnotes

2nd Annual Henry Ford Medical Group Research Symposium. April 15, 2004, Detroit, MI. [Poster]

10th Annual HMO Research Network Conference, May 5, 2004. Detroit, MI [Oral]

Society for General Internal Medicine, May 14, 2004. Chicago, IL [Poster]

American Society for Bone and Mineral Research, October 3, 2004, Seattle, WA [Poster]

132nd Annual Meeting of APHA, November 8, 2004, Washington, DC. [Poster]

Funded by: Merck & Co., Inc.

Reference

- 1.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Osteoporosis in Postmenopausal Women: What’s New; An Overview of Recommendations. AHRQ Publication No. APPIP02-2005. 2002.

- 2.National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF). Physician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Washington, DC. NOF, 1999

- 3.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: recommendations and rationale. Ann Intern Med 2002; 137(6):526–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Morris CA, Cabral D, Cheng H, et al. Patterns of bone mineral density testing: Current guidelines, testing rates, and interventions. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(7):783–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. CH. 4. 2004. Washington, D.C.

- 6.Department of Health and Human Services. Access to Quality Health Services. Objectives for Improving Health (Part A: Focus Areas 1–4). In: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Health Resources and Services Administration, editor. Healthy People 2010. 2000:1–42.

- 7.Church TR, Yeazel MW, Jones RM, et al. A randomized trial of direct mailing of fecal occult blood tests to increase colorectal cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(10):770–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Slater JS, Henly GA, Ha CN, et al. Effect of direct mail as a population-based strategy to increase mammography use among low-income underinsured women ages 40 to 64 years. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(10):2346–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Toth-Pal E, Nilsson GH, Furhoff AK. Clinical effect of computer generated physician reminders in health screening in primary health care—a controlled clinical trial of preventive services among the elderly. Int J Med Inform. 2004;73(9–10):695–703. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Schmittdiel J, McMenamin SB, Halpin HA, et al. The use of patient and physician reminders for preventive services: Results from a National Study of Physician Organizations. Prev Med. 2004;39(5):1001–06. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Szilagyi PG, Bordley C, Vann JC, et al. Effect of patient reminder/recall interventions on immunization rates. A review. JAMA. 2000;284(14):1820–27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Smith DM, Zhou XH, Weinberger M, Smith F, McDonald RC. Mailed reminders for area-wide influenza immunization: A randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(1):1–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Balas EA, Weingarten S, Garb CT, Blumenthal D, Boren SA, Brown GD. Improving preventive care by prompting physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(3):301–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Feldstein A, Elmer PJ, Orwoll E, Herson M, Hillier T. Bone mineral density measurement and treatment for osteoporosis in older individuals with fractures: A gap in evidence-based practice guideline implementation. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(18):2165–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Siris ES, Brenneman SK, Barrett-Connor E, et al. The effect of age and bone mineral density on the absolute, excess, and relative risk of fracture in postmenopausal women aged 50–99: Results from the National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment (NORA). Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:565–74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Melton LJ, III, Kan SH, Frye MA, Wahner HW, O’Fallon WM, Riggs BL. Epidemiology of vertebral fractures in women. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(5):1000–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Barrett JA, Baron JA, Karagas MR, Beach ML. Fracture risk in the U.S. Medicare population. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52(3):243–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Ullom-Minnich P. Prevention of osteoporosis and fractures. Am Fam Physician. 1999;60(1):194–202. [PubMed]

- 19.White B, Fisher WD, Laurin DA. Rate of mortality for elderly patients after fracture of hip in the 1980’s. J Bone Jt Surg. 1987;69(9):1335–40. [PubMed]

- 20.Cauley JA, Thompson DE, Ensrud KC, Scott JC, Black D. Risk of mortality following clinical fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11(7):556–61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Florida Osteoporosis Board. Incidence and Economic Burden of Osteoporotic Fractures in The United States, 21005-2025. 2005.

- 22.Feldstein AC, Nichols GA, Elmer PJ, Smith DH, Aickin M, Herson M. Older women with fractures: patients falling through the cracks of guideline-recommended osteoporosis screening and treatment. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2003;85-A(12):2294–302. [PubMed]

- 23.Solomon DH, Morris C, Cheng H, et al. Medication use patterns for osteoporosis: An assessment of guidelines, treatment rates, and quality improvement interventions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80(2):194–202. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Osteoporosis in Postmenopausal Women: Recommendations and Rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:526–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Solomon DH, Finkelstein JS, Polinski JM, et al. A randomized controlled trial of mailed osteoporosis education to older adults. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(5):760–67. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Wroe AL, Salkovskis PM. The effects of ‘non-directive’ questioning on an anticipated decision whether to undergo predictive testing for heart disease: An experimental study. Behav Res Ther. 2000;38(4):389–403. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Stock JL, Waud CE, Coderre JA, et al. Clinical reporting to primary care physicians leads to increased use and understanding of bone densitometry and affects the management of osteoporosis. A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128(12 Pt 1):996–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Silverman SL, Greenwald M, Klein RA, Drinkwater BL. Effect of bone density information on decisions about hormone replacement therapy: A randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89(3):321–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Torgerson DJ, Thomas RE, Campbell MK, Reid DM. Randomized trial of osteoporosis screening. Use of hormone replacement therapy and quality-of-life results. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(18):2121–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Rolnick SJ, Kopher R, Jackson J, Fischer LR, Compo R. What is the impact of osteoporosis education and bone mineral density testing for postmenopausal women in a managed care setting? Menopause. 2001;8(2):141–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.LaCroix AZ, Buist DS, Brenneman SK, Abbott TA, III. Evaluation of three population-based strategies for fracture prevention: Results of the osteoporosis population-based risk assessment (OPRA) trial. Med Care. 2005;43(3):293–302. [DOI] [PubMed]