Abstract

Background

Despite accurate diagnostic tests and effective therapies, the management of osteoporosis has been observed to be suboptimal in many settings. We tested the effectiveness of an intervention to improve care in patients at-risk of osteoporosis.

Design

Randomized controlled trial.

Participants

Primary care physicians and their patients at-risk of osteoporosis, including women 65 years and over, men and women 45 and over with a prior fracture, and men and women 45 and over who recently used ≥90 days of oral glucocorticoids.

Intervention

A multifaceted program of education and reminders delivered to primary care physicians as well as mailings and automated telephone calls to patients. Outcome: Either undergoing a bone mineral density (BMD) testing or filling a prescription for a bone-active medication during the 10 months of follow-up.

Results

After the intervention, 144 (14%) patients in the intervention group and 97 (10%) patients in the control group received either a BMD test or filled a prescription for an osteoporosis medication. This represents a 4% absolute increase and a 45% relative increase (95% confidence interval 9–93%, p = 0.01) in osteoporosis management between the intervention and control groups. No differences between groups were observed in the incidence of fracture.

Conclusion

An intervention targeting primary care physicians and their at-risk patients increased the frequency of BMD testing and/or filling prescriptions for osteoporosis medications. However, the absolute percentage of at-risk patients receiving osteoporosis management remained low.

Key words: osteoporosis, cluster randomized controlled trial, academic detailing, quality improvement

Despite accurate diagnostic techniques and effective treatments, many at-risk populations do not receive management for osteoporosis. Studies of postfracture populations document screening and treatment rates below 20% in most settings.1–4 Management of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis has also been observed to be suboptimal.5–7 The relatively straightforward methods for diagnosis and treatment and the huge unmet need suggest that osteoporosis should initially be managed by primary care physicians in most instances.8 However, previous assessments found that primary care physicians often regard osteoporosis as a low priority, and many do not see the value in screening and treatment.9

Several trials aimed at improving osteoporosis management have been published.10–17 These have focused on educating patients, scheduling bone mineral density (BMD) testing, and posttest counseling. Many of these interventions appear effective, but few have been evaluated in randomized controlled trials, most have been tested in a single site, and the ability to widely implement such programs may be limited. We designed and tested an educational program targeting primary care physicians and their at-risk patients to improve osteoporosis management. Principles of academic detailing, including one-on-one adult learning with action-oriented messages, guided design of the intervention.18 We tested our multifaceted program to improve osteoporosis management among primary care physicians in a randomized controlled trial.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a randomized controlled trial among primary care physicians and their at-risk patients. All patients in the study group were beneficiaries of a large health care insurer, Horizon Blue Cross Blue Shield of New Jersey (HBCBSNJ). In addition, they were all considered at-risk of osteoporosis (see Study Population for details) and had not undergone bone mineral density (BMD) testing nor received a medication for osteoporosis during a 26-month baseline period. To improve the efficiency of our physician-targeted intervention, only primary care physicians with at least 4 at-risk beneficiaries were selected for randomization. The intervention occurred over a 3-month period, September 1, 2004–November 30, 2004, and endpoints were assessed over 10 months, beginning with the start of the intervention through June 24, 2005.

All aspects of the trial were approved by the Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board.

Intervention

The main intervention consisted of one-on-one educational visits with primary care physicians. The visits were conducted by specially trained pharmacists who work with HBCBSNJ as physician educators. These pharmacists also underwent a 1-day training program focused on osteoporosis and conducted by 2 of the study authors. This program included lectures on the epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of osteoporosis. Also, it reviewed principles of academic detailing18 and the specific goals of this intervention. Mock scripts were used for practicing physician encounters, and several follow-up teleconferences were conducted to review materials, practice educational encounters, and provide logistical support to the educators.

We developed a continuing medical education (CME) program (accredited by Harvard Medical School’s CME department) that was distributed in the setting of the physician visit. The materials consisted of brief summaries of osteoporosis epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Also, we provided doctors with an algorithm for diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis and a guide to osteoporosis pharmacotherapy. A version of this material was reproduced on 1 double-sided laminated card small enough to fit into a coat pocket. The educators also offered the doctors and their staff “tear sheets” for patients that resembled prescription pads with check boxes for fall prevention, calcium and vitamin D use, bone mineral density testing, and treatment. We supplied patient materials on fall prevention to the primary care physician’s office staff. (All materials available upon request.) In addition, the study paid for doctors to apply for CME credit if they completed a postvisit test.

Each primary care physician in the intervention groups received a list of her HBCBSNJ patients at-risk for osteoporosis. The educators used this list during the one-on-one visit with doctors to give examples of patients that should be considered for BMD testing and/or treatment.

Patients in the intervention group received an introductory letter from HBCBSNJ and then an automated telephone call from HBCBSNJ inviting them to undergo BMD testing. This call employed interactive voice response technology that has been used for other screening tests.19 We have described this aspect of the intervention in detail in another related paper.20 Such automated calling provides tailored education through a branching logic algorithm. For example, persons who had never had a BMD test but expressed an interest were offered specific encouragement, “it’s great that you plan on having a bone density test; the best way to tell if a person is at risk for osteoporosis is to have a bone density test. The test only takes about 5 minutes, you don’t have to take off your clothes, and it’s painless.” At the conclusion of the educational call, patients were able to transfer directly to a centralized radiology service to schedule a BMD test.

Study Population

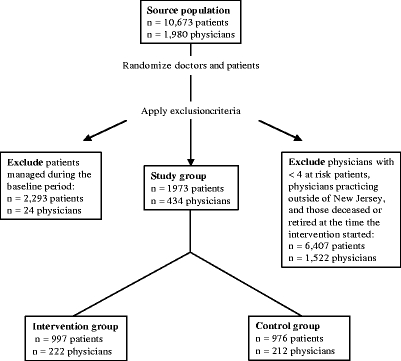

The assembly of the study population is described in Fig. 1. Our goal was to identify at-risk patients who had not recently received osteoporosis management, either a BMD test or a medication for osteoporosis. The initial study population consisted of beneficiaries of HBCBSNJ who had at least 2 continuous years of enrollment before the intervention and a prescription drug benefit. To ensure that subject’s prescription drug claims were through HBCBSNJ, we required that they filed at least 1 prescription claim with HBCBSNJ in each of the 2 baseline years. Patients who were Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in HBCBSNJ would have all of their health care claims paid by HBCBSNJ.

Figure 1.

This flow chart shows how the study population was assembled.

From this group of patients, we identified populations at-risk for osteoporosis using demographic information and health care utilization data, such as diagnoses, medication use, surgical procedures, and hospitalizations. The at-risk groups included: women 65 years of age and over; women and men 45 and older with a prior fracture of the hip, spine, forearm, or humerus; and women and men 45 and older who had used oral glucocorticoids for at least 90 days. These determinations were based on data from the 26-month baseline period.

To improve the efficiency of our intervention, 2 further exclusions were applied. First, patients who had undergone a BMD test or filled at least 1 prescription for an osteoporosis medication during the baseline 26 months were excluded. Because the study dataset does not permit clear determination of this group’s need for further management, the analyses focused on the population who had neither undergone BMD testing nor filled a prescription for an osteoporosis medication during the baseline period. Second, we excluded patients whose primary care physicians (as listed by HBCBSNJ) had less than 4 eligible HBCBSNJ beneficiaries at-risk for osteoporosis.

Study Outcome and Covariates

Bone mineral density (BMD) testing and use of an osteoporosis medication formed the main study outcome. Osteoporosis medications included hormone therapy, calcitonin, raloxifene, bisphosphonates, and teriparatide. Each component of the main outcome was examined individually.

We assessed patient characteristics during the baseline period using the health care utilization information. These data included demographics, physician and hospital visits, diagnoses and procedures such as prior fractures, comorbid conditions,21 laboratory and radiology tests (i.e., BMD tests), and prescription medication use. In addition, we examined the characteristics of primary care physicians in both groups. All patients in HBCBSNJ must designate a primary care provider. Eligible primary care providers include subspecialists of Internal Medicine, such as endocrinologists and rheumatologists.

Statistical Analyses

We compared the intervention and control groups in their baseline characteristics. The effect of the intervention was determined using a regression model that accounted for the clustered structure of the data. Because patients are clustered within a given primary care physician’s practice, we used a Generalized Estimating Equations approach with a working variance–covariance matrix that assumed an independent structure. Subgroup analyses focused on the different at-risk groups: women 65 and over, men and women with a fracture, or men and women who used oral glucocorticoids. These groups are not mutually exclusive. Both unadjusted and adjusted analyses (controlling for baseline covariates) were performed in PROC GENMOD in SAS Version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

The eligible study population included 4,266 patients and their 458 primary care physicians. As noted in Fig. 1, 2,293 (54%) underwent a BMD test or received an osteoporosis medication during the baseline period, and the primary analyses focus on the remaining 1,973 patients and their 434 primary care physicians. The intervention and control groups were well balanced with respect to most characteristics (Table 1). As expected, the mean age of patients was approximately 70 and more than 90% were female. During the baseline period, 1 in 10 patients had a prior fracture and about one-quarter had used oral glucocorticoids. The average primary care physician was 50 years old, a man, and trained in Internal Medicine. About one-third trained in family practice. Only 6 physicians in total (3 in intervention and 3 in control) subspecialized in endocrinology or rheumatology.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients and Physicians Based on Data from the 2 Years Prior to the Intervention

| Intervention | Control | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | N (%) or mean ± standard deviation | ||

| N | 997 | 976 | |

| Age, years | 68 ± 9 | 69 ± 8 | |

| Female gender | 895 (90) | 922 (94) | < .001 |

| Physician visits | 13 (7, 22) | 13 (6, 22) | .7 |

| Number of medications, median (IQR) | 12 (7, 18) | 11 (7, 18) | .5 |

| Fractures | 134 (13) | 95 (10) | .01 |

| Use of oral glucocorticoids | 237 (24) | 199 (20) | .07 |

| Comorbid conditions, median (IQR) | 1 (0, 2) | 1 (0, 2) | .1 |

| Physician characteristics | |||

| N | 222 | 212 | |

| Number of at-risk patients, median (IQR) | 4 (2, 5) | 3 (2, 5) | .08 |

| Age | 50 ± 9 | 50 ± 10 | .7 |

| Female gender | 40 (18) | 33 (16) | .5 |

| Training* | .3 | ||

| Family medicine | 87 (39) | 69 (33) | |

| Internal medicine | 99 (44) | 101 (48) | |

| Internal medicine subspecialty | 37 (17) | 42 (20) | |

Patient characteristics were based on data from the 26-month baseline period. P values are from chi-square tests for categorical data. For continuous variables, p values were taken from Student’s t test for normally distributed data and from Wilcoxon 2-sample test for non-normal data. Comorbid conditions were categorized based on reference # 21.

*The training categories are mutually exclusive. Family medicine subspecialists (n = 8) are grouped into family medicine. Endocrinologists (n = 4) and rheumatologists (n = 2) are grouped into Internal Medicine subspecialist; they were equally distributed between intervention and control groups.

BMD = bone mineral density; IQR = interquartile range

In Table 2, we present the results of the intervention, showing small absolute but large relative effects. Patients in the intervention group were significantly more likely to undergo BMD testing (all tests were for dual energy x-ray absorptiometry), receive a medication for osteoporosis, or have had at least 1 of these outcomes than patients in the control group. The relative increases ranged from 43% to 60%, but the absolute increases were small. To understand whether the slight baseline imbalances between intervention and control groups might have affected our results, we ran adjusted models that controlled for baseline covariates (see Table 2); these results were very similar to the unadjusted findings.

Table 2.

Management of Osteoporosis During Follow-up

| Intervention (n = 997) | Control (n = 976) | Unadjusted results | Adjusted results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative risk of endpoint among intervention versus control (95% CI) | p value | Relative risk of endpoint among intervention versus control (95% CI) | p value | |||

| N (%) | ||||||

| Underwent BMD test | 126 (13) | 86 (9) | 1.43 (1.06–1.94) | .02 | 1.48 (1.08–2.04) | .01 |

| Medication for osteoporosis | 59 (6) | 36 (4) | 1.60 (1.04–2.49) | .03 | 1.73 (1.09–2.75) | .02 |

| Either of the above | 144 (14) | 97 (10) | 1.45 (1.09–1.93) | .01 | 1.52 (1.13–2.05) | .006 |

The relative risk refers to the increase in likelihood that a subject in the intervention group would receive osteoporosis management compared with the control subjects. These analyses account for the clustering of patients within physicians’ practices using Generalized Estimating Equations.

BMD = bone mineral density; RR = relative risk; CI = confidence interval.

Table 3 shows the results from subgroup analyses. The effects of the intervention among women 65 years and older and people with a prior fracture were consistent with, if not slightly stronger than, the results among the total population. The intervention may not have been effective among the subgroup of patients who had used glucocorticoids; however, small sample size in several of the subgroups precludes definitive statements regarding the intervention’s effect.

Table 3.

Management of Osteoporosis During Follow-up Among Selected Subgroups

| Subgroup endpoint | Intervention | Control | Unadjusted results | Adjusted results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative risk of endpoint among intervention versus control (95% CI) | p value | Relative risk of endpoint among intervention versus control (95% CI) | p value | |||

| N (%) | ||||||

| Women 65 and over | ||||||

| N | 819 | 861 | ||||

| Underwent BMD test | 115 (14) | 81 (9) | 1.49 (1.09–2.04) | .02 | 1.48 (1.07–2.04) | .02 |

| Medication for osteoporosis | 54 (7) | 35 (4) | 1.67 (1.05–2.65) | .03 | 1.65 (1.04–2.62) | .03 |

| Either one | 131 (16) | 92 (11) | 1.59 (1.14–2.22) | .006 | 1.50 (1.11–2.03) | .008 |

| Men or women with fractures | ||||||

| N | 134 | 95 | ||||

| Underwent BMD test | 11 (8) | 4 (4) | 1.95 (0.64–6.00) | .2 | 2.86 (1.15–7.07) | .02 |

| Medication for osteoporosis | 6 (4) | 1 (1) | 4.41 (0.52–37) | .2 | 10.67 (0.81–141) | .07 |

| Either one | 13 (10) | 5 (5) | 1.93 (0.67–5.66) | .2 | 2.73 (1.19–6.28) | .02 |

| Men or women using oral glucocorticoids | ||||||

| N | 237 | 199 | ||||

| Underwent BMD test | 23 (10) | 19 (10) | 1.02 (0.57–1.82) | .9 | 1.05 (0.57–1.93) | .9 |

| Medication for osteoporosis | 14 (6) | 15 (8) | 0.77 (0.38–1.58) | .5 | 0.92 (0.45–1.87) | .8 |

| Either one | 32 (14) | 24 (12) | 1.14 (0.64–2.01) | .7 | 1.29 (0.78–2.13) | .3 |

These subgroup analyses consisted of the 1,680 women 65 and over, 229 men or women with fractures, and the 436 men or women who used oral glucocorticoids who did not undergo a BMD test or receive a medication during the 26-month baseline period. These subgroups are not mutually exclusive. These analyses account for the clustering of patients within physicians’ practices using Generalized Estimating Equations.

RR = relative risk; CI = confidence interval

In an attempt to understand the effects of the different parts of the multifaceted intervention, we examined the success of the one-on-one educational sessions with physicians and the automated telephone calls to schedule BMD tests with patients. Of the physicians in the intervention group, we were able to conduct educational visits with 94% of them. These visits averaged 15 minutes (standard deviation = 9). The automated telephone calls to patients in the intervention arm resulted in 708 calls successfully reaching the correct person. Of these patients, 54 transferred to schedule a BMD test, but only 3 made an appointment for a BMD test while on the telephone.

DISCUSSION

We conducted a randomized controlled trial to improve osteoporosis care in at-risk patients by their primary care physicians. The intervention combined one-on-one education for physicians with patient-specific recommendations and a patient-targeted automated telephone program for scheduling BMD tests. Patients seen by physicians in the intervention group were 45% more likely than those in the control group to undergo a BMD test or fill a prescription for osteoporosis during follow-up; however, this translated into only a 4% absolute increase. Similar increases were also observed in the subgroup of patients with prior fractures, exactly the group that the National Committee on Quality Assurance has chosen to focus on.3

Several aspects of this intervention should be carefully examined. First, was the correct population studied? We targeted at-risk patients seen by primary care physicians who had not undergone testing and/or received a medication for osteoporosis in the prior 26 months. It is possible that these patients had been offered testing and/or treatment and declined such management. We could have focused on patients who recently sustained a fracture, but our goal was to include a broader cohort of at-risk patients. However, by targeting patients who had not recently sustained a fracture and who had not received testing or treatment during the baseline period, we focused on a group that may have been particularly difficult to reach with a quality improvement program. They represent a large and relevant target for such an intervention, but our relatively low absolute improvement may be partly attributable to these factors. Second, was the intervention appropriate?

Academic detailing has been found effective for improving physician behavior associated with many clinical situations.22–25 It provides one-on-one education that is both patient-specific and can be generalized across a physician’s practice. Some question the transferability of academic detailing. It is labor intensive and requires an infrastructure to be successful. However, based on a vast literature, it is one of the reliable methods for improving care.23–25 Australia has a nationwide academic detailing program that has been successfully running for approximately 10 years, and 5 provinces in Canada also have similar program. Recently, 2 US states (Kentucky and Pennsylvania) have embarked on broad-based academic detailing programs as well. Thus, whereas the intervention we tested is not easily reproduced, many health systems around the world have embraced academic detailing because of its proven benefits and thus our intervention may become increasingly relevant.

The interactive voice recognition (IVR) calls to the patients did not appear effective. Whereas this technology appears useful for reminding patients about routine screening, such as mammograms and pap smears,19 it may not be optimal when patients require more than a reminder. Because many patients are not familiar with BMD testing, we did include an educational component to the IVR calls, but still they did not prompt many patients to schedule these tests.

The absolute increase of 4% in osteoporosis management may not be clinically important. These differences represent large relative increases after a brief intervention among patients who may be somewhat recalcitrant. But, only 14% of the at-risk patients that were included in the intervention group underwent BMD testing or received a medication. Thus, even our statistically significant increase may not be large enough to translate into clinically meaningful improvement. The cost of this intervention was substantial. The materials, mailing, training, and visit costs were approximately $40,000 for this start-up program. Whereas these costs are high partly because of the expense of initiating a program, it is not clear that a 4% increase in screening and/or treatment of osteoporosis is worth this investment. If the program was run for long enough and actual fracture rates were reduced, the program may reduce overall costs to a health system. Because we did not perform a formal cost-effectiveness analysis, these comments are speculative.

Our findings are limited by the fact that we focused on 2 process measures—BMD testing and medication use—and not actual clinical endpoints, such as fracture. We did not see any differences in fracture rates between the 2 groups, but the study was not powered for this outcome. The effectiveness of osteoporosis treatments suggests that the fracture rates would decrease in the intervention group if the medication use persisted. However, osteoporosis medication persistence is suboptimal.26 Receipt of a BMD test and/or use of a medication for osteoporosis define the outcome adopted by the National Committee on Quality Assurance for their HEDIS criteria.3 Reliance on health care utilization data and not clinical records probably misclassified some patients as at-risk for osteoporosis who may not have been. We may have missed some heal ultrasound tests that patients may have obtained without insurance coverage. Also, we did not have information on over-the-counter use of calcium and vitamin D supplements, hip protectors, or advice offered by a health care provider. However, by using health care utilization data and not medical records, we required fewer resources for identifying at-risk patients and their outcomes. It is also possible that a longer follow-up period would have yielded more complete information.

Other interventions targeting improvement for the management of osteoporosis have employed different interventions. Gardner and colleagues also employed an education and reminder program that was found successful.16 This randomized trial enrolled 80 patients admitted to 1 medical center after a hip fracture. All patients received a brief educational session; this session included a printed copy of 5 questions to bring to their primary care physician for intervention patients. Six weeks after Surgery intervention, patients received a follow-up reminder telephone call. During 6 months of follow-up, 42% of intervention patients had their osteoporosis managed compared with 19% in the control arm. Several other osteoporosis interventions have also found benefits larger than what we observed, from 1% to 40%.10–13,15,17

It may be the case that the results of an academic detailing approach such as ours could be improved by also incorporating direct to patient education. We tried to use the IVR approach for patient education, but face-to-face delivery of information may be more effective. Furthermore, other interventions for quality improvement should consider financial incentives for patients who undergo screening studies. Automated reminders for doctors has also been effective in some settings.17

In most populations studied, the gap between accepted recommendations for osteoporosis care and current practice is wide. Moreover, the population at-risk for osteoporosis is large.27 This translates into a pressing need for large-scale quality improvement programs. The relative increases in osteoporosis management that our intervention produced were significant, but the absolute increases were small. It will require longer follow-up to determine whether these improvements are sustained and produce reductions in fractures. We believe that one of the reasons for this intervention’s relative success was a high rate of one-on-one physician visits. It will be important to attempt to replicate these findings among different primary care physicians serving various patient populations. Randomized controlled testing of more potent interventions, perhaps that include point-of-care reminders and incentive programs for physicians, should lead to improved processes of care that result in better patient outcomes.

Acknowledgment

The study was funded by Merck and Co., Inc. Dr. Solomon is also supported by grants from the NIH (AR48616, AG027066), the Arthritis Foundation, and the Engalitcheff Arthritis Outcomes Initiative. The study data were possessed by the study’s principal investigator (DHS) who guarantees their integrity.

Potential Financial Conflicts of Interest Drs Weiss and Chen are both employees of Merck and Co., Inc.

References

- 1.Morris CA, Cabral D, Cheng H, et al. Patterns of bone mineral density testing: current guidelines, testing rates, and interventions. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:783–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Solomon DH, Morris C, Cheng H, et al. Medication use patterns for osteoporosis: an assessment of guidelines, treatment rates, and quality improvement interventions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:194–202. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.http://www.ncqa.org/communications/sohc2004/osteoporosis.htm accessed November 21, 2005.

- 4.Harrington JT, Broy SB, DeRosa AM, Licata AA, Shewmon, DA. Hip fracture patients are not treated for osteoporosis: a call for action. Arthritis Care Res. 2002;47:651–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Buckley LM, Marquez M, Feezor R, Ruffin DM, Benson LL. Prevention of corticosteroid induced osteoporosis: results of a patient survey. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1736–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Yood RA, Harrold LR, Fish L, et al. Prevention of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: experience in a managed care setting. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1322–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Solomon DH, Katz JN, Jacobs JP, et al. Management of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis—rates and predictors of care in an academic rheumatology practice. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:3136–42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Raisz LG. Clinical practice. Screening for osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:164–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Solomon DH, Connelly MT, Rosen CJ, et al. Factors related to the use of bone densitometry: a survey of 494 physicians in New England. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:123–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Majumdar SR, Rowe BH, Folk D, et al. A controlled trial to increase detection and treatment of osteoporosis in older patients with a wrist fracture. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:366–73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Torgerson DJ, Thomas RE, Campbell MK, Reid DM. Randomized trial of osteoporosis screening: use of hormone replacement therapy and quality-of-life results. Arch Intern Med. 197;157:2121–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Newman ED, Starkey RH, Ayoub WT, et al. Osteoporosis disease management: best practices from the Penn State Geisinger Health System. J Clinic Outcomes Manag. 2000;7:23–8.

- 13.Jamal SA, Ridout R, Chase C, Fielding L, Rubin LA, Hawker GA. Bone mineral density testing and osteoporosis education improve lifestyle behaviors in premenopausal women: a prospective study. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:2143–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Chevalley T, Hoffmeyer T, Bonjour JP. An osteoporosis clinical pathway for the medical management of patients with low-trauma fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2002;13:450–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Silverman SL, Greenwald M, Klein RA, Drinkwater BL. Effect of bone density information on decisions about hormone replacement therapy: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:321–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Gardner MJ, Brophy RH, Bemetrakopoulos D, et al. Interventions to improve osteoporosis treatment following hip fracture. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2005;87:3–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Feldstein AC, Elmer PJ, Smith DH, et al. Electronic medical record reminder improves osteoporosis management after a fracture: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriat Soc. 2006;54:450–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Soumerai SB, Avorn J. Principles of educational outreach (‘academic detailing’) to improve clinical decision making. JAMA. 1990;263:549–56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Corkrey R, Parkinson L. Interactive voice response: review of studies 1989–2000. Behav Res Meth Instrum Comput. 2002;34:342–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Polinski JM, Patrick AR, Truppo C, et al. Interactive voice response telephone calls to enhance bone mineral density testing. American Journal of Managed Care. 2006;12:321–5. [PubMed]

- 21.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Soumerai SB, Salem-Schatz S, Avorn J, Casteris CS, Ross-Degnan D, Popovsky MA. A controlled trial of educational outreach to improve blood transfusion practice. JAMA. 1993;270:961–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Avorn J, Soumerai SB. Improving drug-therapy decisions through educational outreach. A randomized controlled trial of academically based “detailing”. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:1457–63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Solomon DH, Van Houten L, Glynn RJ, et al. Academic detailing to improve use of broad-spectrum antibiotics at an academic medical center. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1897–1902. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Thomson O’Brien MA, Oxman AD, Davis DA, Haynes RB, Freemantle N, Harvey EL. Educational outreach visits. Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;4.

- 26.Solomon DH, Avorn J, Katz JN, et al. Compliance with osteoporosis medications. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2414–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General, 2004.