Abstract

A quantitative real-time PCR assay was developed for the determination of antiviral drug susceptibility and growth kinetics of human herpesvirus 6. The susceptibility and fitness of a sensitive strain, HST, and its ganciclovir-resistant derivative, GCVR1, were then characterized, leading us to conclude that the mutations of this latter virus did not alter its fitness significantly.

Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6), a betaherpesvirus closely related to human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), is the causative agent of exanthem subitum (15) and has also been associated with several other diseases, such as encephalitis, multiple sclerosis, and opportunistic infections in transplant recipients (1, 4-6, 10). In vitro HHV-6 susceptibility to antiviral compounds such as ganciclovir (GCV), cidofovir (CDV), and foscarnet (PFA) is broadly similar to that of HCMV. Therapy with these drugs, in the context of HCMV diseases, may inhibit HHV-6 replication significantly, but alternatively, it may also lead to the selection of drug-resistant HHV-6 strains, as suggested by recent findings (9). These findings point out the need for readily accessible susceptibility assays to detect HHV-6 resistance as well as phenotypic tests investigating the replication capacity (fitness) of resistant viruses to understand the dynamics of resistance emergence. Different methods, such as evaluation of cytopathic effect, immunofluorescence assay, DNA hybridization, and flow cytometry, have been used previously (2, 3, 8, 11). However, these approaches remained limited by the low infectious titers of HHV-6 stocks and the long incubation times (at least 7 days of culture) necessary to measure relevant markers of virus replication. In that context, the recent report of a real-time TaqMan PCR applied to HHV-6 DNA quantitation offered the opportunity to improve the sensitivity of evaluation of HHV-6 growth in the presence of antiviral drugs (7).

Development of a real-time TaqMan PCR susceptibility assay.

MT4 cells were infected with either the HST strain of HHV-6 or its GCV-resistant derivative GCVR1 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01 50% tissue culture infective dose per cell and incubated in 24-well plates under different concentrations of acyclovir (ACV), GCV, CDV, and PFA as previously described (8). At day 7 postinfection (D7), the cells were collected and the susceptibility of the two viruses to the four drugs was determined by using flow cytometry and real-time PCR in parallel. Monoclonal antibody 7C7 (Argene Biosoft, Varilhes, France), recognizing a nuclear viral protein of 116 kDa (12), was used for the quantitation of HHV-6 antigen expression by flow cytometry (8). Real-time PCR was used for the quantitation of both the number of HHV-6 DNA copies and that of human albumin gene copies (twice the number of cells), with a sensitivity threshold of 10 copies per run and a variation of cycle threshold (CT) below 5% in each case (7). The results of flow cytometry assays obtained in duplicate experiments (Table 1) confirmed that according to 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s), HST was highly sensitive to CDV (7.4 μM), sensitive to GCV (10.1 μM) and PFA (21 μM), and resistant to ACV (48.5 μM). Its resistant counterpart GCVR1 exhibited a decreased susceptibility to CDV, GCV, and ACV, with IC50s of 186, 226, and 455 μM, respectively, while the sensitivity to PFA was only slightly modified (IC50, 60.4 μM). The results of real-time TaqMan PCR led to essentially the same classification as flow cytometry regarding both the activity of the four drugs against HST and the resistance profile of GCVR1, as shown by resistance indices (RI) (Table 1). However, the IC50s were consistently lower with real-time PCR than flow cytometry, demonstrating that a significant inhibition of viral DNA replication was obtained at lower drug concentrations than that associated with antigen expression.

TABLE 1.

Determination of the IC50 of HST and GCVR1 by using either flow cytometry or real-time TaqMan PCR

| Antiviral drug | IC50 (μM)a

|

RIb

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HST

|

GCVR1

|

|||||

| Cytometry | TaqMan | Cytometry | TaqMan | Cytometry | TaqMan | |

| ACV | 48.5 ± 16.3 | 22.5 ± 25.0 | 455.0 ± 116 | 166.5 ± 142.2 | 9.4 | 7.4 |

| GCV | 10.1 ± 1.3 | 9.0 ± 1.6 | 226.0 ± 198 | 28.0 ± 1.6 | 22 | 3.1 |

| CDV | 7.4 ± 1.3 | 8.0 ± 3.5 | 186.0 ± 36.8 | 70.5 ± 21.4 | 25.0 | 9.8 |

| PFA | 21 ± 12.7 | 22.5 ± 6.6 | 60.4 ± 44.5 | 40.0 ± 1.7 | 2.8 | 1.8 |

IC50 was derived from inhibition curves as the concentration of antiviral drug that reduced the marker of virus replication (either immunofluorescent cells or DNA copies) by 50% compared to that observed in the absence of the drug.

RI was computed as the ratio of GCVR1 IC50 to HST IC50.

Given the high sensitivity of real-time PCR, it was tempting to define a novel susceptibility assay by using lesser amounts of cells and viruses as well as a shorter incubation time. For that purpose, MT4 cells were infected with either HST or GCVR1 at a MOI of 0.004 tissue culture infective dose per cell and incubated in 96-well microplates, with 2 × 104 cells per well. The real-time PCR readout was performed at two different times postinfection, namely, D7, as previously carried out, and D3. The two incubation times permitted the plotting of clearly dose-dependent inhibition curves for both HST and GCVR1 (not shown), while the IC50 derived from these curves at D3 and D7 showed an acceptable reproducibility in duplicate experiments (Table 2). Compared with the results obtained at D7 using the original format of real-time PCR assay (Table 1), the microformat assay provided lower IC50, apart from results for GCVR1 grown in the presence of GCV, which were 28 and 43 μM with the original format and microformat assays, respectively. In parallel, RI at D7 were also lower in the case of microformat assay, except for results for GCV. Under these conditions, the susceptibility of GCVR1 to PFA appeared unmodified compared with that of HST. The readout at D3 gave IC50 and RI within the same order of magnitude as those obtained at D7, demonstrating the possibility of shortening the incubation period without any significant loss of information. Accordingly, despite the differences of IC50s and the rather high interassay variability, the microformat assay at D3 correctly recognized the acquired resistance of GCVR1 to ACV, GCV, and CDV. Of note, real-time PCR measured DNA content, which was basically more related to the mechanism of action of DNA polymerase inhibitors and theoretically less dependent on either MOI or cellular support than viral antigen expression. According to preliminary data, the overall efficiency of PCR assay was not modified when either a 10-fold-higher MOI or primary HHV-6 isolates growing on peripheral blood mononuclear cells were used (not shown). This reflected its robustness and adaptability, confirming similar recent results obtained with a herpes simplex virus real-time PCR assay (13).

TABLE 2.

Determination of the IC50 of HST and GCVR1 by using microformat cell culture and real-time TaqMan PCR

| Antiviral drug | IC50 (μM)a

|

RIb

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HST

|

GCVR1

|

|||||

| D3 | D7 | D3 | D7 | D3 | D7 | |

| ACV | 14.8 ± 0.5 | 19.8 ± 3.6 | 83.3 ± 9.2 | 110.8 ± 7.7 | 5.6 | 5.6 |

| GCV | 3.9 ± 1.7 | 5.6 ± 0.1 | 27.9 ± 2.6 | 43.0 ± 0.7 | 7.2 | 7.7 |

| CDV | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 19.2 ± 0.3 | 14.7 ± 2.1 | 10.9 | 5.4 |

| PFA | 9.9 ± 4.8 | 12.8 ± 8.5 | 10.9 ± 8.6 | 9.6 ± 6.4 | 1.1 | 0.7 |

IC50 was derived from inhibition curves as the concentration of antiviral drug that reduced the marker of virus replication (either immunofluorescent cells or DNA copies) by 50% compared to that observed in the absence of the drug.

RI was computed as the ratio of GCVR1 IC50 to HST IC50.

Analysis of viral replication capacity.

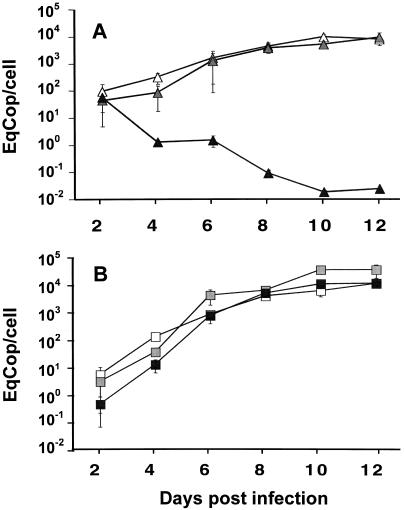

The fitness of resistant virus and its selective advantage over wild-type virus in the presence or absence of antiviral are important parameters for the emergence of resistance as well as the balance between drug-sensitive and drug-resistant virus populations in vivo. We used the MT4 cell cultures in 96-well microplates to investigate the dynamics of HST and GCVR1 replication. The growth of the two viruses was analyzed over 12 days in the absence of drug and in the presence of 4 and 32 μM GCV. Compared with the growth in the absence of GCV, the growth of the two viruses at these concentrations close to their respective IC50 (computed at D3) was slightly delayed during the first 4 days of culture, as exemplified by the fourfold reduction of HST DNA with 4 μM GCV and the 10-fold reduction of GCVR1 DNA with 32 μM GCV at D4 (Fig. 1). This inhibition effect virtually disappeared at D8, while the load of viral DNA progressively increased to a steady-state value close to 104 copies per cell. In contrast, the load of HST DNA with 32 μM GCV, which far exceeded its IC50 (Table 1), progressively decreased and was below 2 copies per 100 cells by D10 (Fig. 1A). Except for this case, the variation of HHV-6 DNA in cell cultures appeared to be biphasic. The first part of the curve fit the exponential growth model of virus replication, as the neat result of occurrence of novel cell infections and death of previously infected cells. The second part of the curve corresponded to a steady state of the mean HHV-6 DNA content, which appeared to reflect a complex balance between the infection, death, and division of cells. As previously reported, a chronically infected cell line consisting of a mixture of infected cells and cells refractory to infection may be established, with the refractoriness being transient and possibly related to differential expression of receptors and/or cytokines (14). As a conclusion, the growth of both viruses was not consistently impaired when the GCV concentration was close to the respective IC50s, confirming that IC50, albeit being a valuable parameter for the characterization of virus susceptibility, was not sufficient to control virus infection and propagation either in vitro or in vivo.

FIG. 1.

Growth curves of HST and GCVR1 in individual infections. MT4 cells were infected either by a standardized inoculum of HST (A) or GCVR1 (B). Infection was carried out in the absence of drug (open symbols) and in the presence of 4 μM (gray symbols) or 32 μM (black symbols) GCV. Every 2 days postinfection, cells were collected, and HHV-6 DNA was quantified by real-time PCR. The number of cells in samples was determined by the same approach, and the final result was expressed as the number of HHV-6 equivalent genome copies per cell (EqCop/cell).

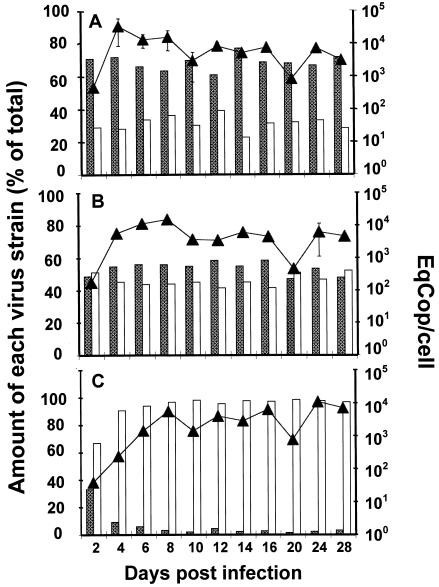

In order to approach more closely the physiological conditions of infection in vivo, both sensitive and resistant viruses were grown together over a period of 28 days using the same conditions as for individual infections except that 50% of infected cells were removed and replaced by fresh uninfected cells every 8 days. The overall HHV-6 DNA load was quantified by means of real-time PCR, while the amounts of HST and GCVR1 were evaluated through the analysis of restriction patterns using PciI. Briefly, two primers, PolA6 (5′-ACA GTT GCG TGA CGA AGG AGT-3′) and PolB6 (5′-AAG CTC GAA GAA ATG GAC ATC-3′), were used to amplify a 614-bp sequence of the U38 gene (HST nucleotide sequence, accession number AB 021506) in which a C-to-T substitution at the position 2882 is specific for GCVR1 and generates one additional PciI restriction site (9). The relative amounts of HST and GCVR1 were computed from the intensities of the corresponding specific bands following PciI digestion, thanks to a regression curve established from calibrated mixtures of both viruses tested in parallel. The growth curve of the two viruses taken as a whole (Fig. 2) exhibited an increase of virus cell load within the first 4 to 8 days of culture until the approximate value of 104 copies per cell was reached. The rate of increase was highest in the absence of drug and lowest in the presence of 32 μM GCV, in agreement with the kinetics of individual infections (Fig. 1). The profile of the steady-state replication following initial increase was regularly altered by the removal of infected cells and the addition of uninfected ones every 8 days: a significant decrease was then observed at the subsequent measurement (D10 and D20) and was followed by a reincrease of this parameter (D12 and D24). The ratio of HST to GCVR1 remained unchanged in the absence of drug (with mean percentages of 69 and 31%, respectively) (Fig. 2A) and at the GCV concentration of 4 μM (54 and 46%, respectively) (Fig. 2B) throughout the follow-up of coculture, showing neither a selective advantage of HST over GCVR1 in the absence of GCV nor an advantage of GCVR1 over HST in the presence of 4 μM GCV. In contrast, with 32 μM GCV, the percentage of HST sharply decreased starting from 30% at D2: the value of 3% was observed at D10 and remained broadly unchanged until the end of the study (Fig. 2C). In all cases, the results of coculture experiments appeared to reflect the simple addition of viral growth kinetics in monoculture experiments (Fig. 1). This ruled out a major role of a possible intracellular complementation between both viruses, in accordance with the low expected rate of cell coinfection resulting from the low initial MOI. These results do not support the idea of impaired fitness of GCVR1 compared to HST, and they point out the risk of long-term persistence of multiresistant viruses, even in the absence of selective pressure, and their possible reemergence when drugs are administrated again at high doses.

FIG. 2.

Growth curves of HST and GCVR1 in coculture experiments. MT4 cells were simultaneously infected with HST (shaded columns) and GCVR1 (open columns). Incubation was performed in the absence of drug (A) and in the presence of 4 μM (B) or 32 μM (C) GCV. At the indicated times, overall viral load was measured (upper lines with triangles) as described in the legend for Fig. 1 and expressed as the number of HHV-6 equivalent genome copies per cell (EqCop/cell). The ratio of the two strains was measured by quantitative analysis of restriction fragment length polymorphism and expressed for each strain as the percentage of total virus present (histograms in the lower part of each panel).

Acknowledgments

M.M. and C.M. contributed equally to this work.

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (ARC). M.M. was the recipient of a fellowship from the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale. C.M. was sponsored by the MENRT (grant no. 98446).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ablashi, D. V., H. B. Eastman, C. B. Owen, M. M. Roman, J. Friedman, J. B. Zabriskie, D. L. Peterson, G. R. Pearson, and J. E. Whitman. 2000. Frequent HHV-6 reactivation in multiple sclerosis (MS) and chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) patients. J. Clin. Virol. 16:179-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agut, H., H. Collandre, J. T. Aubin, D. Guetard, V. Favier, D. Ingrand, L. Montagnier, and J. M. Huraux. 1989. In vitro sensitivity of human herpesvirus-6 to antiviral drugs. Res. Virol. 140:219-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akesson-Johansson, A., J. Harmenberg, B. Wahren, and A. Linde. 1990. Inhibition of human herpesvirus 6 replication by 9-[4-hydroxy-2-(hydroxymethyl)butyl]guanine (2HM-HBG) and other antiviral compounds. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34:2417-2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boutolleau, D., C. Fernandez, E. Andre, B. M. Imbert-Marcille, N. Milpied, H. Agut, and A. Gautheret-Dejean. 2003. Human herpesvirus (HHV)-6 and HHV-7: two closely related viruses with different infection profiles in stem cell transplantation recipients. J. Infect. Dis. 187:179-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Challoner, P. B., K. T. Smith, J. D. Parker, D. L. MacLeod, S. N. Coulter, T. M. Rose, E. R. Schultz, J. L. Bennett, R. L. Garber, M. Chang, et al. 1995. Plaque-associated expression of human herpesvirus 6 in multiple sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:7440-7444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drobyski, W. R., K. K. Knox, D. Majewski, and D. R. Carrigan. 1994. Brief report: fatal encephalitis due to variant B human herpesvirus-6 infection in a bone marrow-transplant recipient. N. Engl. J. Med. 330:1356-1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gautheret-Dejean, A., C. Manichanh, F. Thien-Ah-Koon, A. M. Fillet, N. Mangeney, M. Vidaud, N. Dhedin, J. P. Vernant, and H. Agut. 2002. Development of a real-time polymerase chain reaction assay for the diagnosis of human herpesvirus-6 infection and application to bone marrow transplant patients. J. Virol. Methods 100:27-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manichanh, C., P. Grenot, A. Gautheret-Dejean, P. Debre, J. M. Huraux, and H. Agut. 2000. Susceptibility of human herpesvirus 6 to antiviral compounds by flow cytometry analysis. Cytometry 40:135-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manichanh, C., C. Olivier-Aubron, J. P. Lagarde, J. T. Aubin, P. Bossi, A. Gautheret-Dejean, J. M. Huraux, and H. Agut. 2001. Selection of the same mutation in the U69 protein kinase gene of human herpesvirus-6 after prolonged exposure to ganciclovir in vitro and in vivo. J. Gen. Virol. 82:2767-2776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ratnamohan, V. M., J. Chapman, H. Howse, K. Bovington, P. Robertson, K. Byth, R. Allen, and A. L. Cunningham. 1998. Cytomegalovirus and human herpesvirus 6 both cause viral disease after renal transplantation. Transplantation 66:877-882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reymen, D., L. Naesens, J. Balzarini, A. Holy, H. Dvorakova, and E. De Clercq. 1995. Antiviral activity of selected acyclic nucleoside analogues against human herpesvirus 6. Antiviral Res. 28:343-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robert, C., V. Massonneau, P. Pothier, A. Clement, G. Hejblum, P. Hubert, J. T. Aubin, and H. Agut. 1998. Selection and characterization of two specific monoclonal antibodies directed against the two variants of human herpesvirus-6. Res. Virol. 149:403-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stranska, R., A. M. Van Loon, M. Polman, and R. Schuurman. 2002. Application of real-time PCR for determination of antiviral drug susceptibility of herpes simplex virus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2943-2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang, P., K. Abe, T. Ojima, J. H. Ohyashiki, H. Satoh, T. Maruyama, H. Nagata, H. Tanaka, and K. Yamamoto. 2001. 3′-Fluorine-substitution in 3′-fluorocarbocylic oxetanocin A augments the drug's inhibition of HHV-6 B propagation in chronically infected cultures. Microbiol. Immunol. 45:457-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamanishi, K., T. Okuno, K. Shiraki, M. Takahashi, T. Kondo, Y. Asano, and T. Kurata. 1988. Identification of human herpesvirus-6 as a causal agent for exanthem subitum. Lancet i:1065-1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]