Abstract

The orientation of membrane proteins undergoing fast uniaxial rotation around the bilayer normal can be determined without macroscopic alignment. We show that the motionally averaged powder spectra exhibit their 0° frequency, , at the same position as the peak of an aligned sample with the alignment axis parallel to the magnetic field. This equivalence is exploited to determine the orientation of a β-sheet antimicrobial peptide not amenable to macroscopic alignment, using 13CO and 15N chemical shifts from powder spectra. This powder sample approach permits orientation determination of naturally membrane-disruptive proteins in diverse environments and under magic-angle spinning.

1. Introduction

The orientation of membrane proteins has been traditionally determined in solid-state NMR by means of macroscopically aligned samples (1). When the membrane is uniaxially aligned so that the bilayer normal is parallel to the magnetic field (B0), the NMR spectrum of a single site collapses into a single line at a frequency that reflects the orientation of the protein with respect to the bilayer normal.

However, aligning lipid membranes mechanically on glass plates or magnetically in bicelles is generally difficult. Many proteins cannot be aligned due to their inherent membrane-disruptive or curvature-inducing nature (2). Usually only certain membranes are amenable to alignment for a specific protein. Alignment becomes more difficult as the protein size and concentration increase. For glass-plate samples, it is often difficult to control pH, ion concentration, or other parameters that may be relevant for the function of the membrane protein.

Therefore, it is desirable to determine membrane protein orientation without using macroscopic alignment. In fact, it has been realized that for molecules undergoing fast uniaxial rotational diffusion around the bilayer normal, orientation information can be obtained from unoriented samples (3,4). Uniaxial mobility is present for membrane proteins in liquid-crystalline bilayers as long as the protein is not too large (5), and has been reported for many membrane peptides and proteins such as gramicidin A (6), protegrin-1 (7), KL14 and hΦ19W (8). Here we show a simple way of deriving the equivalence between aligned and powder samples, and apply this principle to β-sheet membrane peptides, which are less well understood than α-helices. 13CO and 15N chemical shift constraints obtained from powder samples are used to determine the orientation of a β-sheet antimicrobial peptide that has been resistant to macroscopic alignment.

2. Materials and Methods

Protegrin-1 (PG-1) and tachyplesin-I were synthesized by Fmoc solid-phase methods as described before (7,9). Unoriented proteoliposome samples were prepared by codissolving the peptide and lipids in chloroform and TFE, lyophilization, and rehydration to 35% water by mass. Aligned samples were prepared as described before (7): the codissolved peptide and lipid organic solution was spread evenly on ~80 μm thick glass plates. The sample was vacuum dried thoroughly, and rehydrated at >95% humidity over a saturated salt solution for several days. The plates were stacked, wrapped in parafilm and sealed for measurements.

All spectra were acquired on a Bruker DSX-400 spectrometer (9.4 Tesla) using a static probe. For aligned samples, a home-built rectangular radiofrequency (rf) coil was used, while unoriented samples were measured in a 5-mm solenoid coil. Typical 1H decoupling field strengths and CP field strengths were 50 kHz.

3. Results and Discussion

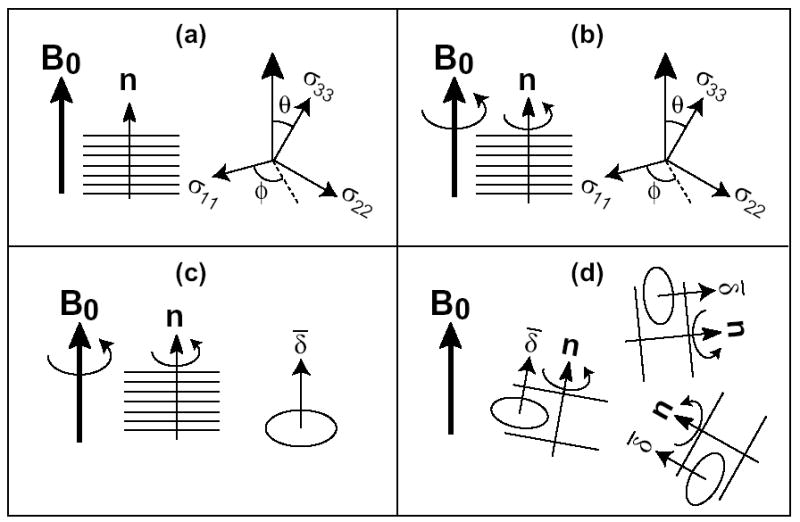

We first derive the equivalence between the frequency of an immobile and uniaxially aligned sample with the alignment axis parallel to the magnetic field B0 (0°-aligned samples), and the 0° frequency, , of a mobile unoriented sample. The frequency of an immobile 0°-aligned sample depends on the polar (θ) and azimuthal (φ) angles of B0 in the principal axis system (PAS) of the relevant interaction tensor (Figure 1a):

Figure 1.

Schematics showing the equivalence between the 0°-aligned spectra and unoriented spectra. (a) Rigid 0°-aligned sample. (b, c) Mobile aligned sample. In (c), the motionally averaged tensor has the unique axis along the bilayer normal. (d) Mobile unoriented sample.

| (1) |

Here δ and η are the anisotropy and asymmetry parameters, respectively, of the rigid-limit interaction tensor. Since B0 is parallel to the alignment axis, (θ, φ) are also the polar coordinates of the bilayer normal in the PAS.

Uniaxial rotation around the bilayer normal in the 0°-aligned sample does not change the frequency, since this rotation is also around the magnetic field and thus does not change (θ, φ) (Figure 1b). Thus, eq. (1) also applies to mobile oriented samples.

For a mobile but unoriented sample, the motional axis is generally not parallel to B0, thus the NMR spectra depend on the anisotropy parameter, , of the motionally averaged tensor (Figure 1d). Since is the frequency difference from the isotropic frequency observed when B0 is along the unique axis of the averaged tensor, which is the motional axis (Figure 1c),

| (2) |

This averaged anisotropy parameter, together with the averaged asymmetry parameter of 0, completely determine the powder lineshape of the protein. The 0°-edge of this powder pattern, which results from bilayer normals parallel to the magnetic field, appears at

| (3) |

In other words, the edge of the motionally averaged powder spectrum is identical to the frequency of the 0°-aligned sample. Thus, one can determine the orientation of membrane proteins using powder samples provided the protein undergoes uniaxial rotation faster than the interaction strength. Moreover, in the static spectra, one can determine from the high-intensity 90° peak, , since the two are related by:

| (4) |

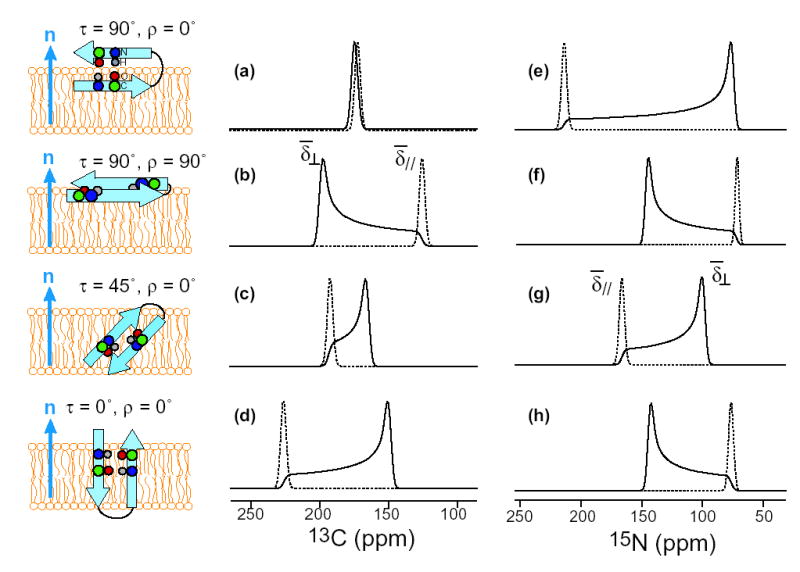

Figure 2 shows calculated motionally averaged 13CO and 15N powder spectra for several orientations of an ideal β-sheet peptide. The peptide was constructed with torsion angles (φ,ψ,ω) of (−139°, +135°, +178°), and exhibits little twist for the short length considered. Thus a single 13CO and 15N label was used to represent the overall orientation. The 13CO and 15N chemical shifts were calculated as a function of the polar coordinates of B0 in a molecule-fixed frame defined by the β-strand axis and β-sheet plane. For the 13CO tensor, rigid-limit principal values of (248, 170, 100) ppm were used in the calculation, the σ22 axis is parallel to the C=O bond, and the σ33 axis is perpendicular to the peptide plane (10). For the 15N tensor, the principal values are (217, 77, 64) ppm, the σ11 axis is 17° from the N-H bond, and the σ33 axis is 25° from the peptide plane (11). Four orientations, defined by the tilt angle (τ) of the β-strand axis from the bilayer normal and the rotation angle (ρ) of the β-sheet plane around the strand axis, were considered. Figure 2 shows that the motionally averaged 13CO and 15N powder spectra are exquisitely sensitive to the β-sheet orientation. For example, when the β-strand axis is perpendicular to the bilayer normal but the β-sheet plane is parallel to it (τ = 90° and ρ = 0°), the 15N powder spectrum has nearly rigid-limit CSA while the 13CO spectrum is extremely narrow (Figure 2a, e). These result from the fact that the 15N σ11 axis and the 13CO σ22 axis are parallel to the bilayer normal at this orientation. When the β-sheet lies in the plane of the bilayer (τ = 90° and ρ = 90°), the 15N CSA is reduced to half the rigid-limit value and inverted in sign (Figure 2f), while the 13CO spectrum has the edge close to σ33 (Figure 2b). For all orientations, the 0°-aligned spectrum shows the same frequency as the edge of the powder pattern.

Figure 2.

Calculated 13CO (a-d) and 15N (e-h) powder spectra (solid lines) and 0°-aligned spectra (dotted lines) of a uniaxially mobile β-sheet peptide for various orientations. (a, e) τ = 90°, ρ = 0°. (b, f) τ = 90°, ρ = 90°. (c, g) τ = 45°, ρ = 0°. (d, h) τ = 0°, ρ = 0°. Note the identity between the frequency of the 0°-aligned spectra and the position of the powder spectra.

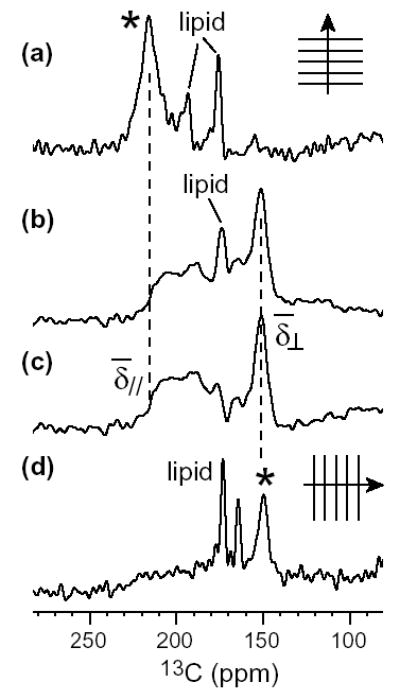

An example of the equivalence between the powder spectra and the oriented spectra for uniaxially mobile molecules is given by PG-1, a β-sheet membrane peptide (12). Figure 3 shows the 13CO spectra of Val16 13CO-labeled PG-1. The 0°-aligned spectrum of PG-1 (a) exhibits a 13CO chemical shift of 216 ppm (7). The unoriented sample gives an axially symmetric powder pattern with = 216 ppm and = 151 ppm (b), much narrower than the rigid-limit CO lineshape (Figure 4f). The powder pattern, obtained with 1H-13C CP, exhibits a sharp lipid signal at ~173 ppm. After subtracting the lipid background signal using a single-pulse 13C spectrum, the difference spectrum of the peptide shows a “magic-angle hole” at the isotropic shift (c). This is characteristic of the CP spectra of uniaxially mobile molecules, where the chemical shift and the dipolar coupling tensors are collinear with the motional axis. When the bilayer normal is 54.7° from B0, the averaged 13C CSA and the 1H-13C dipolar coupling both vanish, thus abolishing CP at the isotropic shift. The singularity of the powder spectrum is identical to the frequency of the 90°-aligned spectrum (d) obtained by tilting the glass plates to make the alignment axis perpendicular to B0. The (216 ppm), isotropic shift (173 ppm), and frequencies (151 ppm) are related by eq. (4) as expected for uniaxial tensors.

Figure 3.

13CO spectra of Val16-labeled PG-1 in DLPC membrane. (a) 0°-aligned spectrum from ref. (7). (b) Powder spectrum obtained with CP. (c) Difference spectrum after subtracting the lipid background signal, showing only the peptide signal. (d) Spectrum of a 90°-aligned sample from ref. (7). The peptide signals in (a) and (d) are indicated by an asterisk.

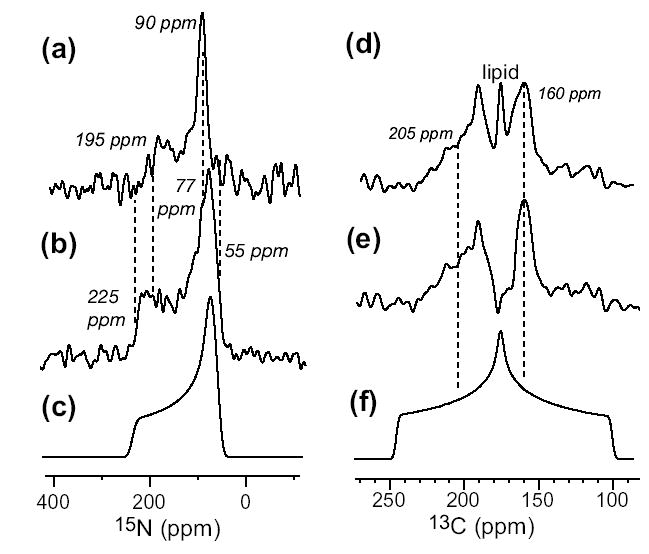

Figure 4.

15N (a, b) and 13CO (d, e) static powder spectra of 15N-Phe4 and 13CO-Val6 labeled TP-I in DLPC membrane (1:15 molar ratio). 15N spectrum at 303 K (a) and 243 K (b) differ in the CSA. (c) Simulated rigid-limit 15N powder pattern. (d) 13CO spectrum of the peptide and the lipids at 303 K. (e) 13CO spectrum of the peptide after subtracting the lipid background signal. (f) Simulated rigid-limit 13CO spectrum.

This motionally endowed favorable frequency equivalence has been exploited indirectly in bicelle-bound membrane proteins (13). When bicelles are aligned magnetically with the alignment axis perpendicular to B0, the fast uniaxial rotation of the protein-bicelle complex yields well-resolved 15N spectra whose frequencies are related to the frequencies of the 0°-aligned glass-plate samples according to eq. (4). We generalize this frequency equivalence to any orientation of the membrane, thus it is not necessary even to prepare bicelles.

It is important to note that the rotational diffusion of membrane proteins differs from that of lipids: most proteins are internally rigid, while the conformational flexibility of lipid molecules prohibits orientation determination even in the presence of global rotational diffusion (14).

We use this powder sample approach to determine the orientation of a β-sheet membrane peptide that has not been amenable to macroscopic alignment so far. Tachyplesin-I is a disulfide-linked β-hairpin antimicrobial peptide found in the hemocytes of the horseshoe crab, Tachyplesus tridentatus (15). Figure 4 shows the static 15N (a, b) and 13CO spectra (d, e) of 15N-Phe4 and 13CO-Val6 labeled TP-I in unoriented DLPC membrane. In the Lα-phase (a), the 15N spectrum shows a uniaxial lineshape, reduced anisotropy ( = 195 ppm), and a magic-angle hole, indicating that TP-I undergoes fast uniaxial rotation. Cooling the peptide to below the phase-transition temperature returned the rigid-limit 15N CSA (b, c). The 13CO spectrum at 303 K after subtracting the lipid background signal also shows a uniaxial lineshape, = 160 ppm and = 205 ppm. The broadness of the edge results from insufficient 1H decoupling on the hydrated membrane sample. But the well-defined singularity and eq. (4) still yield the 0° frequency to ± 5 ppm.

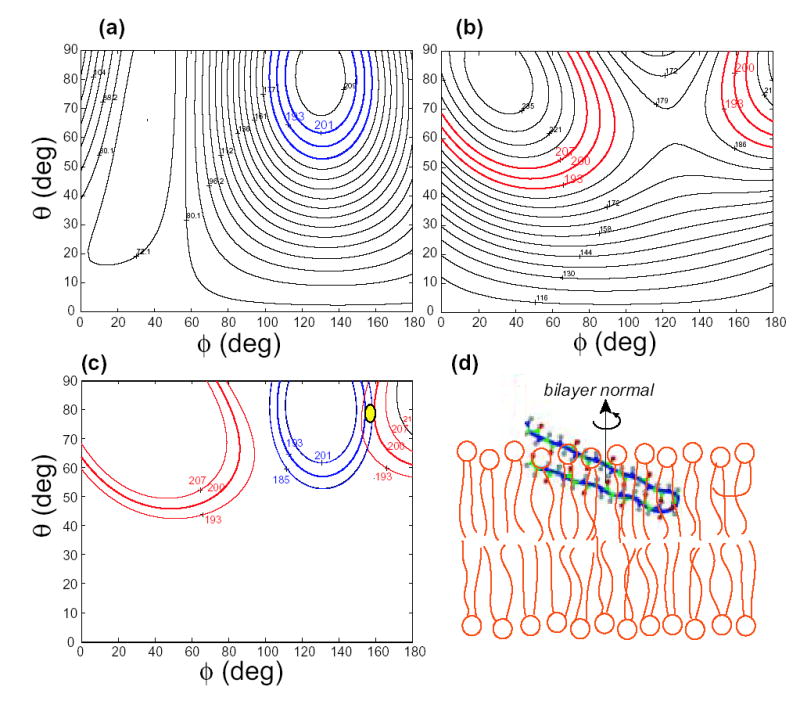

To determine TP-I orientation, we calculate the chemical shifts as a function of (θ, φ) of B0 in the molecule-fixed PDB coordinate system (7). Our recent study of the TP-I conformation indicates that the two strands of the hairpin adopt ideal β-sheet conformation (9) similar to its solution NMR structure in 60 mM DPC micelles (16). The 15N-Phe4 and 13CO-Val6 chemical shift surfaces calculated with this conformation are shown in Figure 5(a, b). The two experimental shifts overlap at a single position, (θ, φ)= (78°, 155°), in the entire orientational space (c). This results in a β-hairpin that is tilted by ~20° from the membrane plane (Figure 5d). The overall in-plane orientation is consistent with 13C-31P distance measurements indicating that Val6 in the N-terminal strand and Gly10 at the β-turn are equidistant from the phosphate headgroups, and 1H spin diffusion data indicating that the peptide is not close to the lipid acyl chains of the membrane (9).

Figure 5.

TP-I orientation from 15N and 13CO chemical shifts. (a) Phe4 15N chemical shift as a function of (θ, φ) of the bilayer normal in the molecule-fixed PDB system. (b) Val6 13CO chemical shift as a function of (θ, φ). The measured chemical shifts with the associated uncertainty are colored. (c) The 13CO and 15N chemical shifts overlap at (θ, φ) = (78°, 155°). (d) TP-I orientation with the bilayer normal in the vertical direction. The peptide and DLPC bilayers are drawn to scale.

4. Conclusion

We have shown by simulation and experiments that in the presence of fast uniaxial rotation, membrane protein orientation can be determined by using unoriented proteoliposomes. Using this approach, we found that the β-hairpin antimicrobial peptide TP-I is oriented roughly parallel to the plane of the DLPC bilayers.

The use of powder samples for orientation determination opens up many spectroscopic and biological possibilities inaccessible to macroscopically aligned samples. This is the only method for determining the orientation of un-alignable proteins such as curvature-inducing antimicrobial peptides. The removal of glass plates or the need for dilute bicelle solutions increases the sample amount in the rf coil, thus increasing sensitivity. The ease of preparing unoriented proteoliposomes allows direct studies of membrane protein orientation as a function of external parameters such as pH and membrane composition. Finally, with powder samples, one can access the large repertoire of magic-angle spinning (MAS) techniques for site-resolved orientation determination. For example, N-H dipolar couplings can be measured by 2D MAS experiments to determine helix orientation, as we will show elsewhere (17).

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. A. J. Waring for providing isotopically labeled PG-1 and TP-I peptides and Prof. K. Schmidt-Rohr for stimulating discussions. This work is supported by a Sloan Research Fellowship and National Institutes of Health grant GM-066976 to M.H.

References

- 1.Opella SJ, Marassi FM. Chem Rev. 2004;104:3587. doi: 10.1021/cr0304121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buffy JJ, McCormick MJ, Wi S, Waring A, Lehrer RI, Hong M. Biochemistry. 2004;43:9800. doi: 10.1021/bi036243w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tian F, Song Z, Cross TA. J Magn Reson. 1998;135:227. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1998.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis BA, Harbison GS, Herzfeld J, Griffin RG. Biochemistry. 1985;24:4671. doi: 10.1021/bi00338a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saffman PG, Delbruck M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:3111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.8.3111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cross TA. Methods Enzymol. 1997;289:672. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)89070-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamaguchi S, Waring A, Hong T, Lehrer R, Hong M. Biochemistry. 2002;41:9852. doi: 10.1021/bi0257991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aisenbrey C, Bechinger B. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:16676. doi: 10.1021/ja0468675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doherty T, Waring AJ, Hong M. Biochemistry2006 doi: 10.1021/bi061424u. submitted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartzell CJ, Whitfeld M, Oas TG, Drobny GP. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:5966. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu CH, Ramamoorthy A, Gierasch LM, Opella SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:6148. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fahrner RL, Dieckmann T, Harwig SS, Lehrer RI, Eisenberg D, Feigon J. Chem & Biol. 1996;3:543. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(96)90145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Angelis AA, Nevzorov AA, Park SH, Howell SC, Mrse AA, Opella SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15340. doi: 10.1021/ja045631y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt-Rohr K, Hong M. J Phys Chem. 1996;100:3861. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamura T, Furunaka H, Tokunaga TMTF, Muta T, Iwanaga S, Niwa M, Takao T, Shimonishi Y. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:16709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mizuguchi M, Kamata S, Kawabata S, Fujitani N, Kawano K. RCSB Protein Data Bank. 1WO1. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cady SD, Hong M. Rocky Mountain Conference on Analytical Chemistry. Breckenridge, CO; 2006. [Google Scholar]