Abstract

Polymers of cell-free hemoglobin have been designed for clinical use as oxygen carriers, but limited information is available regarding their effects on vascular regulation. We tested the hypothesis that the contribution of heme oxygenase (HO) to acetylcholine-evoked dilation of pial arterioles is upregulated 2 days after polymeric hemoglobin transfusion. Dilator responses to acetylcholine measured by intravital microscopy in anesthetized cats were blocked by superfusion of the HO inhibitor tin protoporphyrin-IX (SnPPIX) in a group that had undergone exchange transfusion with hemoglobin 2 days earlier but not in surgical sham and albumin-transfused groups. However, immunoblots from cortical brain homogenates did not reveal changes in expression of the inducible isoform HO1 or the constitutive isoform HO2 in the hemoglobin-transfused group. To test whether the inhibitory effect of SnPPIX was present acutely after hemoglobin transfusion, responses were measured within an hour of completion of the exchange transfusion. In control and albumin-transfused groups, acetylcholine responses were unaffected by SnPPIX but were blocked by addition of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor Nω-nitro-L-arginine (L-NNA) to the superfusate. In hemoglobin-transfused groups, the acetylcholine response was blocked by either SnPPIX or L-NNA alone. The effect of another HO inhibitor, chromium mesoporphyrin (CrMP), was tested on ADP, another endothelial-dependent dilator, in anesthetized rats. Pial arteriolar dilation to ADP was unaffected by CrMP in controls but was attenuated 62% by CrMP in rats transfused with hemoglobin. It is concluded that 1) polymeric hemoglobin transfusion acutely up-regulates the contribution of HO to acetylcholine-induced dilation of pial arterioles in cats, 2) this upregulation persists 2 days after transfusion when 95% of the hemoglobin is cleared from the circulation, and 3) this acute upregulation of HO signaling is ubiquitous in that similar effects were observed with a different endothelial-dependent agonist (i.e., ADP) in a another species (rat).

Keywords: blood substitute, carbon monoxide, cat, endothelial-dependent releasing factor, nitric oxide, oxygen carrier, rat

HEME OXYGENASE (HO) metabolizes heme derived from a variety of degraded heme-containing proteins, including hemoglobin (Hb). Carbon monoxide (CO) generated by HO produces vasodilation, which is thought to be mediated by stimulation of guanylyl cyclase, by direct effects on calcium-activated potassium (KCa) channels and possibly by other pathways (8, 33, 35, 58). A role for CO in regulating cerebrovascular vasodilatory responses derived from the constitutive HO isoform (HO2) has been demonstrated in newborn pigs (25). The increase in cerebral blood flow (CBF) evoked by systemic administration of kainate was found to be attenuated by administration of the HO inhibitor tin protoporphyrin-IX (SnPPIX) in adult rats (32). However, other evidence for a physiological role of HO2 in cerebrovascular regulation in the adult brain is limited. In addition to HO2, the HO1 isoform can be induced by heme that is derived from the administration of hemin or Hb (4, 47, 52). Induction of HO1 has been found to alter vascular reactivity in the lung, intestines, and kidney (9, 37, 39).

Cell-free, chemically modified Hbs have been developed as O2-carrying transfusion fluids (57). Six-hour exposure of cultured endothelial cells to an early generation of cell-free Hb composed of diaspirin cross-linked tetramers increased HO activity, presumably because of the release of heme from the methemoglobin component of the solution (34). Solutions of Hb now undergoing clinical trials (15, 16, 20) are polymers of heterogeneous size that are less likely to extravasate and produce arterial hypertension than the early generation of cross-linked Hb tetramers (31, 44). In addition, polymerization of Hb can decrease the rate of release of heme from methemoglobin (6). The possibility that transfusion of Hb polymers upregulates vascular HO1 sufficiently to alter signaling processes that control arteriolar vasodilation has not been well studied.

In the present study, we evaluated cerebrovascular responses to the endothelial-dependent dilator acetylcholine (ACh) after exchange transfusion of a large Hb polymer that does not rapidly extravasate or cause arterial hypertension (31). Responses to ACh were tested because some evidence shows that in pulmonary arteries, in addition to nitric oxide (NO), CO derived from HO2 can contribute to relaxation evoked by ACh (61). Although cross-linked tetrameric Hb has been reported to attenuate ACh-induced dilation in isolated, perfused hearts (36), previous work in cats showed that pial arteriolar dilation evoked by ACh and ADP (an endothelial-dependent agonist) remained unimpaired acutely after transfusion of cross-linked tetrameric Hb (3). Moreover, the ACh and ADP responses were completely blocked by an inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase (NOS), thereby indicating that the presence of Hb in the plasma does not scavenge all NO produced by the endothelium in a vascular bed with tight endothelial junctions. The current investigation tested the hypothesis that the vasodilatory response of pial arterioles to ACh in the cat would become dependent on HO activity 2 days after transfusion of a cell-free Hb polymer, as assessed by the use of SnPPIX. Responses were also evaluated acutely after transfusion of the polymer to confirm the findings obtained previously with the tetrameric Hb, showing that the ACh response still was dependent on NOS activity. Furthermore, the effect of another HO inhibitor, chromium mesoporphyrin (1, 28), was investigated with ADP in the rat to determine whether the effects of Hb transfusion are specific for ACh and the cat.

METHODS

Hemoglobin preparation

Bovine Hb was purified and stabilized by first reacting with bis(3,5-dibromosalicyl)adipate to form intramolecular cross-links (24). The cross-linked tetramers were then treated with 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethyl-aminopropyl)carbodiimide to form covalent amide bonds between the Hb tetramers without residual attachment of the cross-linking reagent, as previously described (31). The solution was subjected to diafiltration through a 300-kDa Pellicon cassette to separate large molecular weight, polymerized Hb from the remaining tetramers and small polymers. The solution contained Hb molecules with an estimated average radius of 250 Å and nominal molecular mass of ~20 MDa. The purified large polymers were transferred into lactated Ringer solution by dialysis, detoxified with Detoxi-Gel (Pierce, Rockford, IL), irradiated to avoid any endotoxin contamination, and stored at −70°C. The polymerization process resulted in a loss of subunit cooperativity and the Bohr effect, and the P50 of the solution was ~4 mmHg. The Hb concentration in the final solution was between 11 and 12 g/dl, of which ~15% was methemoglobin. The colloid osmotic pressure was ~10 mmHg (cat plasma: ~15 mmHg).

Surgical procedures on cats

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conformed to the principles of laboratory animal research outlined by the American Physiological Society and the National Institutes of Health Guidelines. Anesthesia and surgical procedures were similar to that previously described (42). In brief, laboratory-bred, mixed breed, male cats (2.0–3.4 kg) were initially anesthetized with 2–3% halothane for oral intubation. The lungs were mechanically ventilated with a gas mixture containing ~30% O2. Femoral arteries and veins were catheterized for performing exchange transfusion, monitoring arterial blood pressure, withdrawing arterial blood samples, and infusing anesthetics. After catheterization, halothane administration was stopped, and anesthesia was maintained by intravenous infusion of pentobarbital (6 mg/kg + 12 mg·kg−1 · h−1) and fentanyl (50 μg/kg + 80 μg·kg−1 · h−1). A craniotomy was performed over the parietal cortex, the dura was carefully incised and retracted, and a closed cranial window was secured to the skull. The window consisted of a plastic ring with an inlet, an outlet, and a pressure-monitoring port, as well as a thermistor for monitoring fluid temperature. Esophageal temperature was maintained at ~39°C by use of a warm water-circulating blanket, and window fluid temperature was maintained at ~38°C by use of a heating lamp. Arterial blood gases and pH were measured with a blood gas analyzer (Chiron Diagnostics, Halstead, Essex, UK), and Hb concentration was measured with a hemoximeter (OSM3, Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark). Internal diameter of pial arterioles was measured with an intravital microscopy and video recording system.

NOS activity

Nω-nitro- L-arginine (L-NNA) was used to inhibit cortical NOS activity. To determine the effective dose of L-NNA in this experimental model, the window was superfused with either 30 μM (n = 4) or 300 μM (n = 4) of L-NNA. SnPPIX was selected as an HO inhibitor because of its selectivity for HO over NOS and soluble guanylyl cyclase (61) and because its specificity is supported by its loss of efficacy in HO2 null mice (7, 11, 14). To determine the effect of SnPPIX on NOS activity in the current model, the window was superfused with 10 μM (n = 4) and 30 μM (n = 4) of SnPPIX. Catalytic activity of NOS was determined in the underlying parietal cortex and contralateral parietal cortex by measuring conversion of [14C]arginine to [14C]citrulline, as previously described (38).

Acute effects of transfusion on ACh response

Baseline measurements were obtained ~30 min after completion of the surgery. Baseline vessel reactivity was measured by superfusing the window with 10 μM 2-chloroadenosine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for 5 min at a rate of 0.9 ml/min. Cats then underwent either no transfusion (control group) or an isovolumetric exchange transfusion with either a 5% human serum albumin solution (albumin group) or a 12% zero-link bovine Hb polymer solution (Hb groups). The solutions were infused intravenously at a rate of 1.9 ml/min while arterial blood was withdrawn at the same rate. The arterial hematocrit was reduced to ~20% over a 30-min period. Measurements were repeated 15 min after completion of the transfusion. Diameter measurements were then made 5 min after superfusing the window with 10 and 30 μM ACh. The window was then superfused with 10 μM SnPPIX for 25 min in control (n = 8), albumin-transfused (n = 8), and Hb-transfused (n = 7) cats. In another group of Hb-transfused cats (n = 5), the window was superfused with 300 μM L-NNA instead of SnPPIX. Control and albumin-transfused groups were not studied with only L-NNA because previous work demonstrated that the ACh dilatory response was inhibited by this dose of L-NNA in cats (3). Responses to 10 and 30 μM ACh were repeated starting 5 min after the end of the SnPPIX or L-NNA superfusion period. Next, the window was superfused with a combination of 10 μM SnPPIX and 300 μM L-NNA for a 25-min period. Five minutes after completion of this superfusion, responses to 10 and 30 μM ACh were again repeated. At the end of the experiment, vascular reactivity to 10 μM 2-chloroadenosine was again measured to determine whether vasodilatory ability remained intact.

Chronic effects of transfusion on ACh response

A similar experimental protocol was performed 2 days after the transfusion, when Hb was largely cleared from the circulation. Under halothane anesthesia and aseptic conditions, catheters were chronically implanted in the femoral artery and vein and routed subcutaneously to the cat’s back, where they exited into a protective jacket. On the next day, an exchange transfusion was performed with either a 5% albumin solution (n = 8) or the zero-link Hb polymer (n = 8) in the unanesthetized state. A surgical sham group (n = 8) without an exchange transfusion was also studied because anesthesia and surgery may be sufficient to transiently induce HO1 1 day after surgery (35). Two days after the transfusion (3 days after the initial surgery), the cats underwent the same surgical procedures for constructing a cranial window with the same anesthetic regimen used in the acute experimental protocol. The sequence and dose for superfusing drugs were similar to those in the acute transfusion protocol: 2-chloroadenosine, ACh, ACh following treatment with SnPPIX, ACh following combined treatment with SnPPIX and L-NNA, and again 2-chloroadenosine. Vasodilation to the ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channel agonist pinacidil (10 μM) was also tested. At the end of the protocol, cats were euthanized with an intravenous injection of KCl.

Immunoblotting

In subgroups of cats, the brain was removed at the end of the experiment, and tissue samples from parietal cerebral cortex (~500 mg contralateral to the cranial window) were rapidly frozen for Western analysis blotting. Samples were homogenized and centrifuged, and the supernatants underwent ultracentrifugation to obtain a microsomal fraction to be loaded onto 10% SDS-PAGE gels (30 μg protein/lane determined by the Bradford assay) for protein electrophoresis at 4°C for 90 min. Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, pretreated with 3% milk, and probed overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: 1) rabbit polyclonal anti-HO1 (1:1,000 dilution; Stressgen, Vancouver, Canada); 2) rabbit polyclonal anti-HO2 (1:1,000 dilution; Stressgen); 3) rabbit anti-endothelial NOS (1:4,000 dilution; Sigma); and 4) rabbit polyclonal anti-actin (1:5,000 dilution; Sigma). After being washed, the membrane was incubated with anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:2,500 dilution; Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) for 1 h at room temperature. The immunoblots were developed with ECL (Amersham) and quantified by optical density measurements of the following bands: 32 kDa for HO1, 36 kDa for HO2, 133 kDa for endothelial NOS, and 42 kDa for actin. Actin was used to verify similar protein loading in each lane.

ADP response in rats

Anesthesia was induced with isoflurane in male Wistar rats (250–300 g). The lungs were mechanically ventilated through a tracheotomy. Catheters were inserted into two femoral arteries and one femoral vein. Anesthesia was maintained with pentobarbital (50 mg/kg + 20 mg/kg every 90 min ip). A cranial window with inflow and outflow ports and a thermistor was constructed over the parietal cortex for measuring the diameter of pial arterioles. Four groups of rats were studied in which the diameter response to 10 min of superfusion of 100 μM ADP was measured before and after superfusion of inhibitors. In one group (n = 8), 15 μM of chromium mesoporphyrin (CrMP; Porphyrin, Logan, UT) was superfused for 30 min after the baseline response to ADP was tested. This dose has been shown to markedly reduce HO activity without significantly affecting NOS activity (1). In a second group (n = 8), 1 mM L-NNA was superfused for 30 min after the baseline response to ADP was tested. In a third group (n = 7), rats first underwent a 5- to 7-ml exchange transfusion with the zero-link polymeric Hb solution over a 15-min period. The pial arteriolar response to ADP was tested 15 min after completion of the exchange transfusion. The window was then superfused for 30 min with the diluted NaOH vehicle for CrMP followed by a repeat test of the response to ADP. In a fourth group (n = 8), rats underwent an exchange transfusion with the Hb solution as in the third group. After the baseline response to ADP was tested, 15 μM CrMP was superfused for 30 min, followed by a repeat test of the response to ADP. Fluid temperature in the window was maintained at ~37°C during the superfusion.

Drugs

SnPPIX and CrMP were dissolved in 0.1 M NaOH. A stock solution of 10 mM SnPPIX was diluted to 10 μM in artificial CSF. A stock solution of 1.5 mM CrMP was diluted to 15 μM in artificial CSF. Because of the light sensitivity of the metalloporphyrins, the infusion syringe and catheter were wrapped with opaque material and the cranial window was kept covered after infusion of the drug, except briefly at the time of diameter measurements. In addition, the acrylic cement surrounding the plastic ring of the window was made opaque by adding carbon black to the acrylic. Pinacidil was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide at a concentration of 20 mM and diluted to a final concentration of 10 μM in artificial CSF. L-NNA and 2-chloroadenosine were dissolved directly in artificial CSF.

Data analysis

At each measurement time, images were recorded at several sites, and diameter was measured at 10–20 arteriolar segments in each cat and at 4 – 8 segments in each rat. In the cats, segments were grouped by initial diameters of <50 μm (small), 50–100 μm (medium), and >100 μm (large). The percent responses of all arterioles within a particular size group were averaged for each cat. In rats, nearly all vessels had an initial diameter between 20 and 70 μm and were pooled into a single size. For each time point or drug intervention, the percent change in diameter and other physiological measurements were compared among groups by one-way analysis of variance and the Newman-Keuls multiple range test at the 0.05 significance level. In rats, arterial blood values and the percent change in diameter in response to ADP were compared before and after application of a drug inhibitor by paired t-test. Data are presented as means ± SE.

RESULTS

NOS activity

Superfusion of the cranial window with L-NNA decreased NOS catalytic activity in a dose-dependent fashion in the underlying cortex to 60 ± 24% at 30 μM and to 8 ± 4% at 300 μM (percentage of the values in contralateral cortex). Superfusion with 10 μM SnPPIX had no significant effect on NOS activity (115 ± 15% of contralateral cortex), whereas superfusion of 30 μmol/l had a marginal inhibitory effect (76 ± 7%; P < 0.1; n = 4). Based on these results, doses of 300 μM of L-NNA and 10 μM of SnPPIX were used in the remaining experiments.

Acute effects of transfusion on ACh response

Exchange transfusion with albumin and Hb solutions decreased hematocrit by ~40% (Table 1). Plasma Hb concentration was 2.5 ± 0.1 g/dl after transfusion of the cell-free Hb solution. Consequently, whole blood Hb concentration was greater in the Hb-transfused group than in the albumin-transfused group. Arterial PO2 was maintained at 150–200 mmHg throughout the experiment. No differences in arterial PCO2 or pH were observed among groups. Mean arterial blood pressure was unchanged after albumin or Hb transfusion and remained stable throughout the experimental protocol.

Table 1.

Arterial blood analysis in acute experimental protocol for acetylcholine reactivity in cats

| Pretransfusion | Posttransfusion | SnPPIX or L-NNA | SnPPIX + L-NNA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematocrit, % | ||||

| Control | 30±0.6 | 30±0.8 | 30±0.8 | 31±0.8 |

| Albumin | 32±0.6 | 20±0.5* | 20±0.4* | 20±0.4* |

| Hb group A | 31±0.7 | 22±0.7* | 21±0.5* | 21±0.6* |

| Hb group B | 31±0.2 | 21±0.6* | 21±0.7* | 21±0.6* |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | ||||

| Control | 10.9±0.3 | 10.9±0.4 | 11.3±0.4 | 11.8±0.3 |

| Albumin | 11.9±0.2 | 7.9±0.2* | 8.1±0.2* | 8.4±0.4* |

| Hb group A | 11.8±0.3 | 11.3±0.4 | 11.0±0.4 | 10.8±0.3 |

| Hb group B | 11.3±0.4 | 10.5±0.5 | 10.7±0.5 | 10.6±0.3 |

| PCO2, Torr | ||||

| Control | 32.0±0.5 | 32.4±0.5 | 32.5±0.6 | 32.4±0.3 |

| Albumin | 32.4±0.4 | 32.2±0.5 | 32.3±0.4 | 32.1±0.3 |

| Hb group A | 32.5±0.4 | 32.8±0.5 | 33.1±0.3 | 33.0±0.3 |

| Hb group B | 32.4±0.2 | 33.0±0.4 | 33.3±0.7 | 33.2±0.2 |

| pH | ||||

| Control | 7.45±0.01 | 7.44±0.01 | 7.43±0.01 | 7.44±0.01 |

| Albumin | 7.45±0.01 | 7.46±0.01 | 7.44±0.01 | 7.43±0.01 |

| Hb group A | 7.45±0.01 | 7.43±0.01 | 7.43±0.01 | 7.43±0.01 |

| Hb group B | 7.44±0.01 | 7.44±0.01 | 7.45±0.02 | 7.44±0.01 |

| MABP, mmHg | ||||

| Control | 110±5 | 113±5 | 108±6 | 111±4 |

| Albumin | 109±4 | 110±4 | 105±4 | 105±4 |

| Hb group A | 122±3 | 121±5 | 115±5 | 119±6 |

| Hb group B | 108±5 | 109±7 | 107±5 | 105±5 |

Values are means ± SE; MABP, mean arterial blood pressure. Tin protoporphyrin (SnPPIX) was superfused first in control (n = 8), albumin (n = 8), and hemoglobin (Hb) group A (n = 7); Nω-nitro- L-arginine (L-NNA) was superfused first in Hb group B (n = 5).

P < 0.05 from control group.

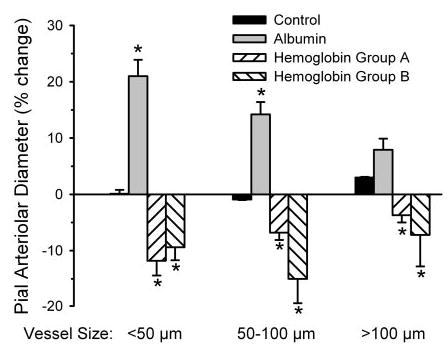

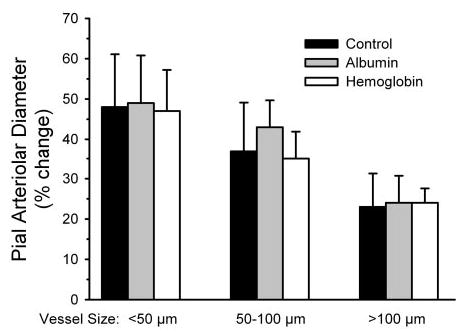

Exchange transfusion with albumin increased the diameter of small, medium, and large pial arterioles, whereas exchange transfusion with Hb decreased the diameter (Fig. 1). These changes in baseline diameter are consistent with previous work (3, 42) in which the albumin-induced dilation is thought to be related to the decrease in arterial O2 content and the Hb-induced constriction is thought to be due to an O2 regulatory mechanism that keeps blood flow and O2 transport constant when blood viscosity is reduced at normal arterial O2 content (41).

Fig. 1.

Percent change in diameter of small, intermediate, and large pial arterioles in a time-control group (n = 8 animals) and 15 min after completion of an exchange transfusion with albumin (n = 8 animals) or polymeric hemoglobin (Hb) solutions. Hb group A (n = 7 animals) subsequently was treated with tin protporphyrin-IX (SnPPIX) first. Hb group B (n = 5 animals) subsequently was treated with Nω-nitro- L-arginine (L-NNA) first. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 from time-control group.

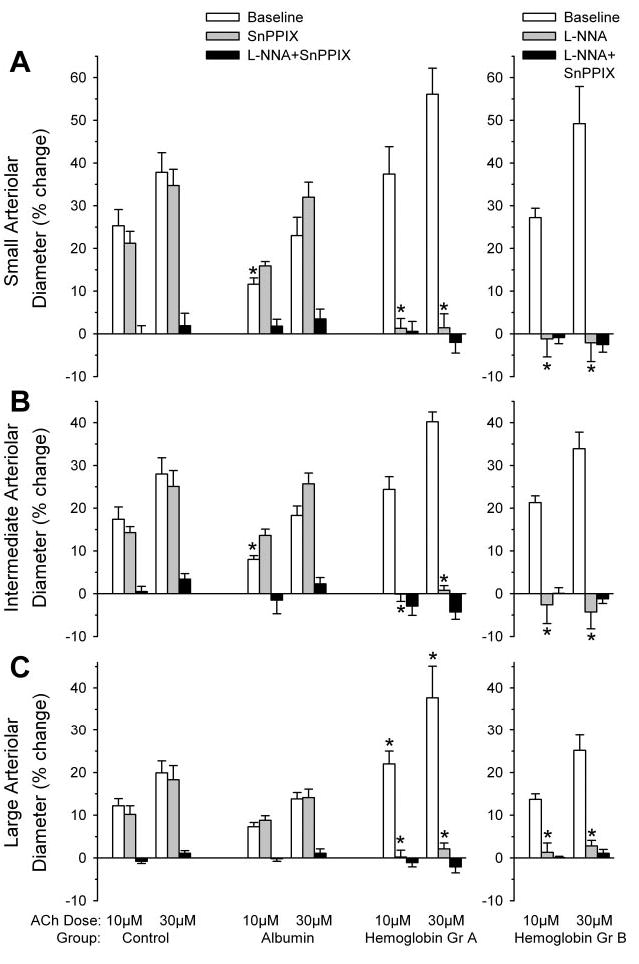

Application of 10 and 30 μM ACh in controls with no transfusion produced dose-dependent dilation, with the greatest percent dilation in the smallest vessels (Fig. 2). The ACh responses were not inhibited by 10 μM SnPPIX but were blocked in vessels of all sizes by the combination of 10 μM SnPPIX and 300 μM L-NNA. Likewise, in the albumin-transfused group, the dilatory response to ACh was not inhibited by SnPPIX but was blocked by the combination of SnPPIX and L-NNA. Transfusion of Hb by itself did not reduce the baseline dilatory response to ACh compared with the control group, and the percent dilation was greater than that in the albumin group. However, unlike the control and albumin groups, the ACh response in vessels of all sizes was completely inhibited by SnPPIX alone (Fig. 2, left). The dilatory response remained blocked with the combination of SnPPIX and L-NNA. In another group transfused with Hb, the dilatory response to ACh was blocked by L-NNA administration alone, as well as with the combination of SnPPIX and L-NNA (Fig. 2, right).

Fig. 2.

Percent change in diameter of small (A), intermediate (B), and large (C) pial arterioles after superfusion of 10 or 30 μM acetylcholine (ACh) in the acute transfusion experiment. Left, ACh responses were tested at baseline, after 10 μM SnPPIX, and after 300 μM L-NNA + 10 μM SnPPIX in a time-control group (n = 8) and in groups transfused with albumin (n = 8 animals) and Hb solutions (Gr A; n = 7 animals). Right, ACh responses were tested at baseline, after 300 μM L-NNA, and after 300 μM L-NNA + 10 μM SnPPIX in a group transfused with Hb solution (Gr B; n = 5 animals). Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 from time-control group at the corresponding ACh dose and number of ACh exposures.

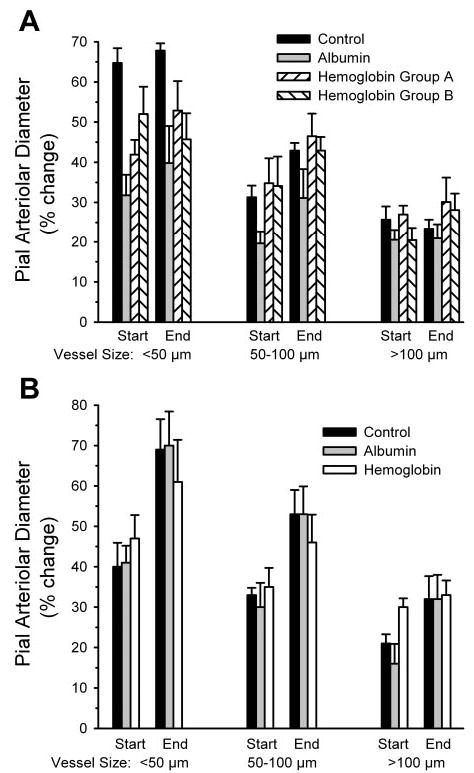

To test whether arterioles were still capable of vasodilation, the response to 10 μM 2-chloroadenosine was tested at the end of the protocol after combined SnPPIX and L-NNA treatment. Topical 2-chloroadenosine produced dilation in each vessel size category in all groups (Fig. 3A). Within each group, the percent dilation to 2-chloroadenosine at the end of the experiment was similar to the response tested before the transfusion.

Fig. 3.

Percent change in diameter of small, intermediate, and large pial arterioles after superfusion of 10 μM 2-chloroadenosine in the acute (A) and chronic (B) transfusion experiments. Dilator responses were tested at the start and end of the experiment (after 300 μM L-NNA + 10 μM SnPPIX superfusion) in the acute and chronic control groups and groups transfused acutely or 2 days earlier with albumin and Hb solutions. In the acute experiment, Hb group A was treated with SnPPIX first, and Hb group B was first treated with L-NNA before combined treatment. Values are means ± SE.

Chronic effects of transfusion on ACh response

A similar protocol was performed 2 days after Hb transfusion when most of the Hb was cleared from the plasma. Results were compared with a surgical sham group and an albumin-transfused group 2 days after surgery. Hematocrit remained reduced at similar levels 2 days after albumin and Hb transfusion (Table 2). However, unlike the acute experiments, whole blood Hb concentration was also similar in the albumin and Hb groups because plasma Hb concentration decreased to 0.1 g/dl. This decrease is consistent with a 10-h plasma half-life previously observed in cats (31). Arterial blood gases and arterial blood pressure were similar among the three groups during testing of ACh reactivity (Table 2).

Table 2.

Arterial blood analysis in chronic experimental protocol 2 days after albumin or hemoglobin transfusion and in a surgical sham control group of cats

| CSF | SnPPIX | SnPPIX + L-NNA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hematocrit, % | |||

| Control | 31±0.7 | 31±0.6 | 32±0.6 |

| Albumin | 22±1.2* | 22±1.1* | 22±0.9* |

| Hemoglobin | 23±1.0* | 23±1.2* | 23±0.9* |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | |||

| Control | 11.5±0.4 | 11.7±0.4 | 12.0±0.4 |

| Albumin | 8.8±0.7* | 8.6±0.6* | 8.9±0.4* |

| Hemoglobin | 9.5±0.4* | 9.2±0.5* | 9.3±0.4* |

| PCO2, Torr | |||

| Control | 32.2±0.4 | 32.6±0.5 | 32.4±0.4 |

| Albumin | 32.8±0.3 | 32.9±0.3 | 32.9±0.2 |

| Hemoglobin | 33.1±0.2 | 33.3±0.5 | 32.7±0.3 |

| pH | |||

| Control | 7.41±0.01 | 7.43±0.01 | 7.42±0.01 |

| Albumin | 7.44±0.01 | 7.43±0.01 | 7.44±0.01 |

| Hemoglobin | 7.43±0.01 | 7.43±0.01 | 7.43±0.01 |

| MABP, mmHg | |||

| Control | 109±5 | 105±4 | 109±5 |

| Albumin | 119±5 | 108±4 | 111±5 |

| Hemoglobin | 115±5 | 114±4 | 113±5 |

Values are means ± SE; n = 8 cats. CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

P < 0.05 from control group.

In the surgical sham-control group, the percent dilation of vessels of different sizes in response to 10 and 30 μM ACh was similar in magnitude to that observed in the control group of the acute experiment (Fig. 4). As in the acute experiment, SnPPIX had no significant effect on the ACh response in the control or albumin-transfused group, whereas the combination of SnPPIX and L-NNA blocked the response. In the group transfused with Hb, the ACh response was intact and similar to that in the surgical sham group. Administration of SnPPIX alone completely inhibited the ACh response 2 days after Hb transfusion, and the combination of L-NNA with SnPPIX produced no additional effect.

Fig. 4.

Percent change in diameter of small (A), intermediate (B), and large (C) pial arterioles after superfusion of 10 or 30 μM ACh in the chronic transfusion experiment. ACh responses were tested at baseline, after 10 μM SnPPIX, and after 300 μM L-NNA + 10 μM SnPPIX in a surgical sham-control group (n = 8 animals) and groups transfused with albumin (n = 8 animals) and Hb solutions (n = 8 animals) 2 days before the experiment. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 from control group at the corresponding ACh dose and number of ACh exposures.

Pial arterioles were still responsive to 2-chloroadenosine after combined SnPPIX and L-NNA superfusion in all three groups (Fig. 3B). Likewise, the dilatory response to the KATP channel agonist pinacidil was similar among the three groups at the end of the experiment (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Percent change in diameter of small, intermediate, and large pial arterioles after superfusion of 10 μM pinacidil at the end of the experiment after 300 μM L-NNA + 10 μM SnPPIX superfusion in the chronic surgical sham-control group and groups transfused 2 days earlier with albumin and Hb solutions. Values are means ± SE; n = 8 animals per group.

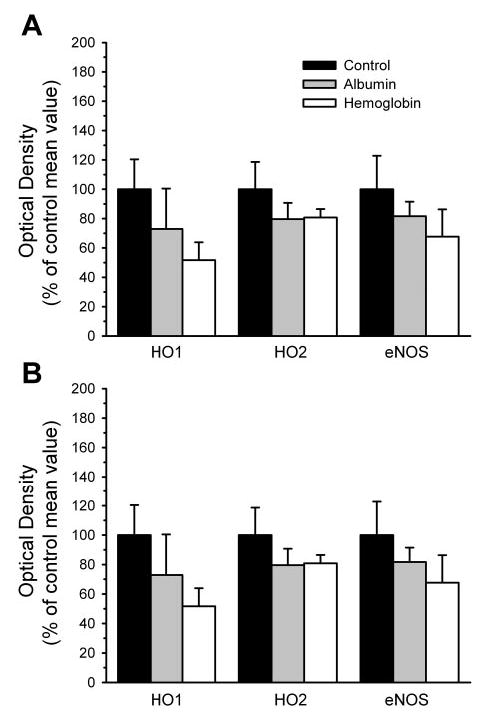

Protein expression

Because an increase in heme can induce HO1 and an increase in HO1 activity could potentially contribute to the SnPPIX sensitivity of ACh response after Hb transfusion, HO1 expression was evaluated in cerebral cortex 2 days after transfusion. In addition, because HO1 is a heat shock protein that can be rapidly induced, HO1 expression was also determined in a subset of cats at the end of the experiment with the acute transfusion protocol. Expression of HO1, HO2, and endothelial NOS in naïve cats that did not undergo surgery and prolonged anesthesia was similar to that in the control groups in the acute and chronic protocols; thus the naïve data and control data were combined into a single group for statistical analysis. No differences in HO1 protein expression could be detected among the control, albumin-transfused, and Hb-transfused groups for either the acute or chronic transfusion experiments (Fig. 6). Also, no differences were observed among groups in the protein expression of HO2 or endothelial NOS.

Fig. 6.

Protein expression of heme oxygenase-1 (HO1), heme oxygenase-2 (HO2), and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) in parietal cortex contralateral to cranial window. Optical density of the immunoblot bands (mean ± SE) is expressed as a percentage of the average value of the control group. A: expression in tissue obtained at the end of the acute transfusion experiment in control group (n = 5; 3 naïve and 2 time-control cats), albumin-transfused group (n = 5), and Hb-transfused group (n = 6). B: expression in tissue obtained at the end of the chronic transfusion experiment (2 days after transfusion) in control group (n = 7; 3 naïve and 4 surgical sham-control cats), albumin-transfused group (n = 5), and Hb-transfused group (n = 4). Analysis of variance did not indicate a significant effect among groups for any of the proteins.

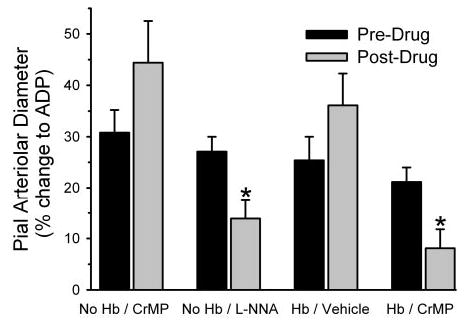

ADP response

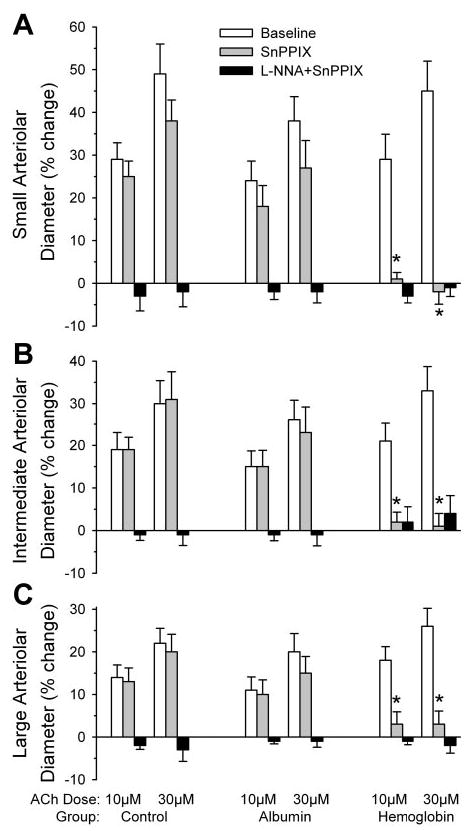

Within each group of rats, mean arterial blood pressure was similar at the time of testing the vascular response to ADP before and after superfusion of CrMP or L-NNA (Table 3). Arterial blood gases were unchanged after superfusion of the inhibitors, although a small decrease in arterial pH occurred in the Hb-transfused group (Table 3). In a control group with no Hb transfusion, superfusion of 100 μM of ADP produced pial arteriolar dilation that was not significantly affected by application of 15 μM CrMP (Fig. 7). In a second group of rats without Hb transfusion, superfusion of L-NNA decreased the dilator response to ADP. In a third group, exchange transfusion of polymeric Hb produced a 12 ± 3% decrease baseline arteriolar diameter. The dilator response to ADP was similar to that in the nontransfused groups and was not altered by superfusion of the vehicle for CrMP. In a fourth group that underwent Hb transfusion, baseline arteriolar diameter decreased by 11 ± 3% after Hb transfusion. In this case, superfusion of CrMP significantly attenuated the response to ADP by 62%. The response after CrMP in the Hb-transfused group was significantly less than the response after CrMP in the control group and less than the response in the Hb-transfused group superfused with vehicle.

Table 3.

Arterial blood analysis in rats tested for ADP reactivity before and after application of CrMP or L-NNA

| CSF | CrMP or L-NNA | |

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | ||

| No Hb/CrMP | 11.3±0.6 | 12.0±0.6* |

| No Hb/L-NNA | 11.6±0.6 | 12.1±0.6 |

| Hb/CrMP | 10.5±0.5 | 10.7±0.5 |

| PCO2, Torr | ||

| No Hb/CrMP | 37.4±0.7 | 37.3±0.6 |

| No Hb/L-NNA | 39.2±1.2 | 37.8±1.2 |

| Hb/CrMP | 38.1±1.3 | 38.2±1.0 |

| pH | ||

| No Hb/CrMP | 7.39±0.01 | 7.39±0.01 |

| No Hb/L-NNA | 7.38±0.01 | 7.39±0.01 |

| Hb/CrMP | 7.38±0.01 | 7.36±0.01* |

| PO2, Torr | ||

| No Hb/CrMP | 123±8 | 113±3 |

| No Hb/L-NNA | 121±5 | 115±5 |

| Hb/CrMP | 134±7 | 130±4 |

| MABP, mmHg | ||

| No Hb/CrMP | 130±6 | 140±3 |

| No Hb/L-NNA | 121±8 | 130±7 |

| Hb/CrMP | 121±8 | 114±6 |

Values are means ± SE; n = 8 rats. CrMP, chromium mesoporphyrin.

P < 0.05 from CSF superfusate by paired t-test.

Fig. 7.

Pial arteriolar diameter responses (means ± SE of percent change) to 100 μM ADP superfusion before (predrug) and after (postdrug) superfusion of chromium mespoprphyrin (CrMP) in groups without Hb transfusion (n = 8 animals) and with Hb transfusion (n = 8 animals), before and after superfusion of vehicle in a group with Hb transfusion (n = 7 animals), and before and after superfusion of L-NNA in a group with Hb transfusion (n = 8 animals). *P < 0.05 from predrug value.

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the hypothesis that transfusion of cell-free polymeric Hb would lead to induction of HO1 and that pial arteriolar responses to the endothelial-dependent dilator ACh would become dependent on HO activity. This hypothesis was based on the work of others (4, 10, 34, 48), which showed that systemic administration of hemin or Hb induced HO1 in various organs and cultured endothelial cells. However, no evidence of HO1 induction could be detected in the brain in either the acute or chronic transfusion protocol, possibly because the circulating heme remains stably bound in the Hb polymer until the polymer is cleared by the reticular endothelial system in the liver, spleen, or lymphatic circulation, nor was any change noted in HO2 or endothelial NOS expression. Nevertheless, pial arteriolar dilation to ACh was selectively dependent on HO activity 2 days after Hb transfusion, as implied by the loss of ACh dilation with treatment of the HO inhibitor SnPPIX.

ACh dependency on HO activity

Unexpectedly, ACh dilation was also completely blocked by SnPPIX after acute Hb transfusion before there would likely be sufficient time for induction of a significant amount of HO1 expression. This dependency on HO activity is presumably mediated by HO2, which is constitutively expressed in most cells and enriched in many neuronal and endothelial cell populations (17, 37, 61). The activity of HO2 can be regulated dynamically by phosphorylation mechanisms (7, 11, 25) and thus has the potential to be activated soon after Hb transfusion. However, CO concentration in the CSF was not directly measured as a marker of HO activity in the present experiment.

It can be surmised that this dependency of ACh dilation on HO activity is not due to the direct effects of reducing hematocrit and associated changes in endothelial wall shear stress, because SnPPIX had no effect in cats with an equivalent reduction in hematocrit after albumin transfusion. Moreover, this shift to a HO dependency of the response is not the result of an increase in arterial pressure and its associated increase in myogenic tone, because the Hb polymer did not produce a pressor response, in agreement with previous studies with this polymer (31, 42).

This acute change in vascular control mechanisms also is not attributable to complete scavenging of NO by the cell-free Hb (41, 46). The dilator response to ACh was not attenuated after Hb transfusion, and the response was completely inhibited by the NOS inhibitor L-NNA, which is consistent with previous work involving tetrameric cross-linked Hb (3). However, in contrast to tetrameric Hb, the polymeric Hb filtered to remove species <300 kDa is too large to appear in renal lymph and does not cause hypertension (31). Thus this Hb polymer is highly unlikely to cross the tight endothelial junctions of the blood-brain barrier and gain access to vascular smooth muscle. However, extravasation may not be necessary for limiting NO availability within arterial smooth muscle. Nonextravasating, cell-free Hb in the plasma might be able to scavenge NO more effectively than red blood cell-based Hb because of Hb entry into the red blood cell-free zone near the vessel wall (29) and because of the resistance to NO diffusion across the plasma space and possibly the red blood cell membrane (18, 30, 51). Mathematical modeling indicates that abluminal NO concentration in the vicinity of smooth muscle can be significantly reduced by a large sink for NO within the lumen provided by nonextravasating Hb (22). However, the reduction of NO concentration in arteriolar smooth muscle in this simulation model was largely dependent on scavenging of NO by capillary Hb because the surface area of capillaries is much greater than that of arterioles. Because of the physical separation provided by the glial limitans, smooth muscle of pial arterioles may be influenced by NO scavenging in parenchymal capillaries to a lesser extent than penetrating arteriolar smooth muscle. Moreover, if NO generated in endothelium occurs in large bursts during agonist stimulation, a significant portion of the NO may escape scavenging by Hb in the plasma (50).

The present results do not completely exclude the possibility that plasma-based Hb reduces basal NO concentration only partially in pial arteriolar smooth muscle, which leads to an activation of HO and production of CO to compensate for the decrease in NO. However, the observation that HO and NOS inhibition did not have additive effects on reducing the ACh dilatory response argues against a simple compensatory mechanism in which the partial loss of NO is replaced by an equipotent amount of CO. Moreover, the persistent inhibitory effect of SnPPIX on the ACh response 2 days after Hb transfusion, when ~95% of the Hb has been cleared from the plasma, also does not support NO scavenging by Hb as the major factor for the upregulation of HO activity in the ACh response.

Heme substrate availability is likely to be a rate-limiting factor for HO activity. A small fraction of the transfused Hb could be transported into endothelial cells, as observed for smaller modified Hb (12), where it could undergo degradation and release of heme. However, the large size of the currently used Hb polymer (~20 MDa) together with our observation that ACh dilation can still be completely blocked by SnPPIX 2 days after Hb transfusion, when the plasma concentration of Hb is reduced approximately 20-fold, argue against these possibilities. Heme can dissociate more readily from methemoglobin than from oxyhemoglobin. Thus another consideration is that heme may dissociate from methemoglobin in plasma and be transported into endothelial cells, where it can cause oxidative stress (34). Although polymerization can slow the rate of release of heme from methemoglobin (6), it is conceivable that the large amount of transfused Hb polymer solution containing ~15% methemoglobin would provide a sufficient amount of dissociable heme to increase HO activity. In this case, persistence of the SnPPIX inhibition of the ACh response 2 days after Hb transfusion might be attributed to cellular clearance of heme lagging behind plasma clearance of polymeric Hb.

The other major effect of Hb transfusion is on oxygenation. Cell-free Hb has the potential to deliver more O2 than red blood cell Hb because the diffusional resistance of the red blood cell membrane and the low O2 solubility of the plasma are overcome by cell-free Hb (21, 40, 45). Although O2 affinity of the polymeric Hb is high, cooperativity is low (Hill coefficient = 1), thereby resulting in an exponential O2-dissociation curve with a non-zero slope in the PO2 range seen in precapillary vessels (53). Thus polymeric Hb is expected to increase periarteriolar PO2 compared with albumin transfusion (54). The difference in the baseline diameter responses between albumin exchange transfusion, which causes dilation, and Hb exchange transfusion, which causes constriction, is probably dependent on differences in oxygenation. Arteriolar dilation, combined with decreased blood viscosity after albumin transfusion, permits CBF to increase by an amount sufficient to maintain convective O2 transport (42). In the case of Hb transfusion, arteriolar constriction offsets the effect of decreased viscosity and results in unchanged CBF and O2 transport (42). When plasma viscosity is increased simultaneously together with Hb transfusion, the pial arteriolar constriction response is converted to a dilatory response that maintains CBF (42). Thus O2-sensing mechanisms appear to tightly control cerebral O2 delivery when blood viscosity is decreased or increased independent of O2-carrying capacity (41). These O2-sensing mechanisms, which operate to limit over oxygenation of the brain after Hb exchange transfusion, could possibly permit an up-regulation of HO activity through phosphorylation of HO2. In addition, HO activity in the placenta has been shown to vary directly with O2 concentration in the physiological range (2). However, in the present study, increased oxygenation is unlikely to account for the HO dependency of the ACh response 2 days after the Hb transfusion, when the total blood Hb concentration was similar to the albumin-transfused group.

Interaction of NOS and HO activity

Increased HO activity has been reported to inhibit NOS and NO-dependent dilation (19, 49). However, the present results indicate that the ACh dilation remains dependent on NO after acute Hb transfusion. The exact mechanism whereby ACh dilation requires both NO and CO after Hb transfusion was not discerned in this study. Although speculative, several issues require consideration in interpreting this complex interaction between NO and CO signaling. First, if Hb does in fact decrease basal NO concentration sufficient to decrease basal cGMP, then increasing the basal CO concentration may maintain basal cGMP concentration in the range where increases in NO evoked by muscarinic receptor activation lead to dynamic increases in cGMP in the vasoactive concentration range. Second, perhaps NO acts as a permissive factor for CO dilation in the adult brain perfused with cell-free Hb, analogous to what has been described for CO-evoked dilation in newborn piglets (27). In piglet pial arterioles, endothelial-derived NO is thought to maintain a minimal amount of protein kinase G activity necessary for CO to activate KCa channels (5, 23, 26). Third, CO and NO may interact on different subunits of the KCa channel (58).

Specificity of HO inhibitors

Specificity of 10 μM of SnPPIX is supported by the lack of effect on NOS catalytic activity in underlying cortex, by the lack of effect on ACh dilation in control and albumin-transfused groups, and by intact dilatory responses to 2-chloroadenosine and pinacidil. However, SnPPIX is known to be photosensitive and to generate CO in solution without heme when exposed to light (55). Therefore, precautions were taken to reduce light exposure to the freshly prepared solution, to use opaque cement around the cranial window, and to keep the window covered except when making diameter measurements. Nevertheless, we cannot exclude the possibility that light exposure during the brief diameter measurement periods generated CO within the window sufficient to alter vascular regulation. For example, exogenous CO is reported to attenuate carbachol-evoked NO release by renal arterioles (49) and to produce constriction by inhibiting NOS (19). However, the observed effect of SnPPIX to completely block the ACh-evoked dilation selectively in the Hb-transfused group is unlikely to be attributable to generation of CO directly from SnPPIX for two reasons. First, if the concentration of CO generated by SnPPIX was adequate to inhibit NOS, then at least a partial inhibitory effect on ACh dilation would have been expected in the non-Hb transfused groups. However, there was no tendency for SnPPIX to reduce the ACh response in the control or albumin-transfused group. Second, NOS activity presumably would have to be almost completely inhibited to fully block the ACh response, yet our ex vivo measurements indicated no significant effect at 10 μM of SnPPIX. Incubation of NOS protein with a CO gas mixture as high as 80% partially inhibited neuronal NOS activity by ~65% (56). Therefore, it is unlikely that CO generated directly from photosensitive SnPPIX fully accounts for the observed complete blockage of ACh-evoked dilation.

Specificity of SnPPIX for acting on HO is also supported by the parallel effects of CrMP, which is less sensitive to light. CrMP did not reduce pial arteriolar dilation to ADP in control rats but markedly reduced the response in Hb-transfused rats. Interestingly, neither CrMP in Hb-transfused rats nor L-NNA in control rats completely blocked the dilation to ADP, in contrast to the complete inhibitory effect of SnPPIX on the ACh response in Hb-transfused cats. Part of this difference may be attributed to a species effect because L-NNA nearly completely blocked the pial arteriolar dilation to ADP in cats (3). Although the response to ADP is endothelial dependent in cerebral vessels (43, 60), others have reported incomplete blockage of ADP dilation by L-NNA in rat and mouse pial arterioles (13, 59). The remaining component appears to be mediated by a hyperpolarizing factor (13, 59).

Implications

The present study indicates that a HO-signaling mechanism can be recruited in the regulation of the cerebrovascular response to ACh and ADP under specific circumstances. Although the mechanism of recruiting HO involvement was not discerned in the present experiments, the similarity of effects of SnPPIX on the ACh response in the cat and of the CrMP on the ADP response in the rat, seen only in the presence of plasma Hb in both cases, indicates that the mechanism of action is ubiquitous. In the chronic experiments, the inhibitory effect of SnPPIX persisted in the Hb-transfused group, despite the decrease in plasma Hb to ~0.1 g/dl. This level of Hb is presumably insufficient to augment NO scavenging. In addition, the amount of O2 carried by the plasma-based Hb at 2 days posttransfusion is of the same order of magnitude as that dissolved in plasma. Thus the beneficial effect of plasma-based Hb on the facilitation of O2 unloading from red blood cell-based Hb is probably minor at this time. These results suggest that transfusion of the Hb polymer induces either expression of signaling proteins not measured in the present experiments or long-term, posttranslational modifications in the state of specific signaling proteins. Furthermore, these findings have clinical implications. Large Phase 3 clinical trials are being conducted with Hb polymers for use in traumatic hemorrhage and surgical procedures associated with significant blood loss (15, 16, 20, 57). The results of the present study indicate that transfusion of a Hb polymer is capable of changing the signaling mechanisms of vascular regulation and that this alteration can persist after most of the Hb has been cleared from the plasma.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Tzipora Sofare for fine editorial assistance in preparing this paper.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

E. Bucci and the University of Maryland are holders of a patent on the zero-link bovine hemoglobin polymer used in this study.

R. C. Koehler and H. Kwansa are paid consultants to Oxyvita, Inc., holder of the licensing rights to the zero-link bovine hemoglobin polymer. The terms of this arrangement are being managed by the Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant NS-38384 (to R. C. Koehler) and by Deutsche Forschungs-gemeinschaft (to A. Rebel).

References

- 1.Appleton SD, Chretien ML, McLaughlin BE, Vreman HJ, Stevenson DK, Brien JF, Nakatsu K, Maurice DH, Marks GS. Selective inhibition of heme oxygenase, without inhibition of nitric oxide synthase or soluble guanylyl cyclase, by metalloporphyrins at low concentrations. Drug Metab Dispos. 1999;27:1214–1219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appleton SD, Marks GS, Nakatsu K, Brien JF, Smith GN, Graham CH. Heme oxygenase activity in placenta: direct dependence on oxygen availability. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H2055–H2059. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01084.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asano Y, Koehler RC, Ulatowski JA, Traystman RJ, Bucci E. Effect of crosslinked hemoglobin transfusion on endothelial dependent dilation in feline pial arterioles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1998;275:H1313–H1321. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.4.H1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balla J, Nath KA, Balla G, Juckett MB, Jacob HS, Vercellotti GM. Endothelial cell heme oxygenase and ferritin induction in rat lung by hemoglobin in vivo. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 1995;268:L321–L327. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.268.2.L321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barkoudah E, Jaggar JH, Leffler CW. The permissive role of endothelial NO in CO-induced cerebrovascular dilation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H1459–H1465. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00369.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bobofchak KM, Mito T, Texel SJ, Bellelli A, Nemoto M, Traystman RJ, Koehler RC, Brinigar WS, Fronticelli C. A recombinant polymeric hemoglobin with conformational, functional, and physiological characteristics of an in vivo O2 transporter. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H549–H561. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00037.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boehning D, Moon C, Sharma S, Hurt KJ, Hester LD, Ronnett GV, Shugar D, Snyder SH. Carbon monoxide neurotransmission activated by CK2 phosphorylation of heme oxygenase-2. Neuron. 2003;40:129–137. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00596-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caudill TK, Resta TC, Kanagy NL, Walker BR. Role of endothelial carbon monoxide in attenuated vasoreactivity following chronic hypoxia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1998;275:R1025–R1030. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.4.R1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christou H, Morita T, Hsieh CM, Koike H, Arkonac B, Perrella MA, Kourembanas S. Prevention of hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension by enhancement of endogenous heme oxygenase-1 in the rat. Circ Res. 2000;86:1224–1229. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.12.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark JE, Foresti R, Sarathchandra P, Kaur H, Green CJ, Motterlini R. Heme oxygenase-1-derived bilirubin ameliorates postischemic myocardial dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H643–H651. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.2.H643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doré S, Takahashi M, Ferris CD, Zakhary R, Hester LD, Guastella D, Snyder SH. Bilirubin, formed by activation of heme oxygenase-2, protects neurons against oxidative stress injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2445–2450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faivre-Fiorina B, Caron A, Fassot C, Fries I, Menu P, Labrude P, Vigneron C. Presence of hemoglobin inside aortic endothelial cells after cell-free hemoglobin administration in guinea pigs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1999;276:H766–H770. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.2.H766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faraci FM, Lynch C, Lamping KG. Responses of cerebral arterioles to ADP: eNOS-dependent and eNOS-independent mechanisms. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H2871–H2876. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00392.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goto S, Sampei K, Alkayed NJ, Doré S, Koehler RC. Characterization of a new double-filament model of focal cerebral ischemia in heme oxygenase-2-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;285:R222–R230. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00067.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gould SA, Moore EE, Hoyt DB, Burch JM, Haenel JB, Garcia J, DeWoskin R, Moss GS. The first randomized trial of human polymerized hemoglobin as a blood substitute in acute trauma and emergent surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:113–120. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(98)00095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gould SA, Moore EE, Hoyt DB, Ness PM, Norris EJ, Carson JL, Hides GA, Freeman IH, DeWoskin R, Moss GS. The life-sustaining capacity of human polymerized hemoglobin when red cells might be unavailable. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;195:445–452. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(02)01335-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grozdanovic Z, Gossrau R. Expression of heme oxygenase-2 (HO-2)-like immunoreactivity in rat tissues. Acta Histochem. 1996;98:203–214. doi: 10.1016/S0065-1281(96)80040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang KT, Han TH, Hyduke DR, Vaughn MW, Van Herle H, Hein TW, Zhang C, Kuo L, Liao JC. Modulation of nitric oxide bioavailability by erythrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:11771–11776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201276698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson FK, Johnson RA. Carbon monoxide promotes endothelium-dependent constriction of isolated gracilis muscle arterioles. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;285:R536–R541. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00624.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kasper SM, Walter M, Grune F, Bischoff A, Erasmi H, Buzello W. Effects of a hemoglobin-based oxygen carrier (HBOC-201) on hemodynamics and oxygen transport in patients undergoing preoperative hemodilution for elective abdominal aortic surgery. Anesth Analg. 1996;83:921–927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kavdia M, Pittman RN, Popel AS. Theoretical analysis of effects of blood substitute affinity and cooperativity on organ oxygen transport. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:2122–2128. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00676.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kavdia M, Tsoukias NM, Popel AS. Model of nitric oxide diffusion in an arteriole: impact of hemoglobin-based blood substitutes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H2245–H2253. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00972.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koneru P, Leffler CW. Role of cGMP in carbon monoxide-induced cerebral vasodilation in piglets. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H304–H309. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00810.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwansa HE, Young AD, Arosio D, Razynska A, Bucci E. Adipyl crosslinked bovine hemoglobins as new models of allosteric systems. Proteins. 2000;39:166–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leffler CW, Balabanova L, Sullivan D, Wang X, Fedinec AL, Parfenova H. Regulation of CO production in cerebral microvessels of newborn pigs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H292–H297. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01059.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leffler CW, Fedinec AL, Parfenova H, Jaggar JH. Permissive contributions of NO and prostacyclin in CO-induced cerebrovascular dilation in piglets. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H432–H438. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01195.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leffler CW, Nasjletti A, Johnson RA, Fedinec AL. Contributions of prostacyclin and nitric oxide to carbon monoxide- induced cerebrovascular dilation in piglets. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H1490–H1495. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.4.H1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leffler CW, Nasjletti A, Yu C, Johnson RA, Fedinec AL, Walker N. Carbon monoxide and cerebral microvascular tone in newborn pigs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1999;276:H1641–H1646. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.5.H1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liao JC, Hein TW, Vaughn MW, Huang KT, Kuo L. Intravascular flow decreases erythrocyte consumption of nitric oxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8757–8761. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu X, Samouilov A, Lancaster JR, Jr, Zweier JL. Nitric oxide uptake by erythrocytes is primarily limited by extracellular diffusion not membrane resistance. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:26194–26199. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201939200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matheson B, Kwansa HE, Bucci E, Rebel A, Koehler RC. Vascular response to infusions of a nonextravasating hemoglobin polymer. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:1479–1486. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00191.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Montecot C, Seylaz J, Pinard E. Carbon monoxide regulates cerebral blood flow in epileptic seizures but not in hypercapnia. Neuroreport. 1998;9:2341–2346. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199807130-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morse D, Sethi J, Choi AM. Carbon monoxide-dependent signaling. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:S12–S17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Motterlini R, Foresti R, Vandegriff K, Intaglietta M, Winslow RW. Oxidative-stress response in vascular endothelial cells exposed to acellular hemoglobin solutions. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1995;269:H648–H655. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.2.H648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Motterlini R, Gonzales A, Foresti R, Clark JE, Green CJ, Winslow RM. Heme oxygenase-1-derived carbon monoxide contributes to the suppression of acute hypertensive responses in vivo. Circ Res. 1998;83:568–577. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.5.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Motterlini R, Macdonald VW. Cell-free hemoglobin potentiates acetylcholine-induced coronary vasoconstriction in rabbit hearts. J Appl Physiol. 1993;75:2224–2233. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.5.2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Naik JS, O’Donaughy TL, Walker BR. Endogenous carbon monoxide is an endothelial-derived vasodilator factor in the mesenteric circulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H838–H845. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00747.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Northington FJ, Tobin JR, Harris AP, Traystman RJ, Koehler RC. Developmental and regional differences in nitric oxide synthase activity and blood flow in the sheep brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17:109–115. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199701000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Donaughy TL, Walker BR. Renal vasodilatory influence of endogenous carbon monoxide in chronically hypoxic rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H2908–H2915. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.6.H2908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Page TC, Light WR, McKay CB, Hellums JD. Oxygen transport by erythrocyte/hemoglobin solution mixtures in an in vitro capillary as a model of hemoglobin-based oxygen carrier performance. Microvasc Res. 1998;55:54–64. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1997.2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qin X, Kwansa H, Bucci E, Roman RJ, Koehler RC. Role of 20-HETE in the pial arteriolar constrictor response to decreased hematocrit after exchange transfusion of cell-free polymeric hemoglobin. J Appl Physiol. 2005;100:336–342. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00890.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rebel A, Ulatowski JA, Kwansa H, Bucci E, Koehler RC. Cerebrovascular response to decreased hematocrit: effect of cell-free hemoglobin, plasma viscosity, and CO2. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H1600–H1608. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00077.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosenblum WI, Nelson GH, Murata S. Endothelial dependent dilation by purines of mouse brain arterioles in vivo. Endothelium. 1994;1:287–294. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sakai H, Hara H, Yuasa M, Tsai AG, Takeoka S, Tsuchida E, Intaglietta M. Molecular dimensions of Hb-based O2 carriers determine constriction of resistance arteries and hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H908–H915. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.3.H908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sakai H, Suzuki Y, Kinoshita M, Takeoka S, Maeda N, Tsuchida E. O2 release from Hb vesicles evaluated using an artificial, narrow O2-permeable tube: comparison with RBCs and acellular Hbs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H2543–H2551. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00537.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sampei K, Ulatowski JA, Asano Y, Kwansa H, Bucci E, Koehler RC. Role of nitric oxide scavenging in vascular response to cell-free hemoglobin transfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H1191–H1201. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00251.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shibahara S, Muller RM, Taguchi H. Transcriptional control of rat heme oxygenase by heat shock. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:12889–12892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takizawa S, Hirabayashi H, Matsushima K, Tokuoka K, Shinohara Y. Induction of heme oxygenase protein protects neurons in cortex and striatum, but not in hippocampus, against transient forebrain ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18:559–569. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199805000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thorup C, Jones CL, Gross SS, Moore LC, Goligorsky MS. Carbon monoxide induces vasodilation and nitric oxide release but suppresses endothelial NOS. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 1999;277:F882–F889. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.277.6.F882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsoukias NM, Kavdia M, Popel AS. A theoretical model of nitric oxide transport in arterioles: frequency- vs. amplitude-dependent control of cGMP formation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H1043–H1056. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00525.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tsoukias NM, Popel AS. Erythrocyte consumption of nitric oxide in presence and absence of plasma-based hemoglobin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H2265–H2277. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01080.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Turner CP, Bergeron M, Matz P, Zegna A, Noble LJ, Panter SS, Sharp FR. Heme oxygenase-1 is induced in glia throughout brain by subarachnoid hemoglobin. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18:257–273. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199803000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vovenko E. Distribution of oxygen tension on the surface of arterioles, capillaries and venules of brain cortex and in tissue in normoxia: an experimental study on rats. Pflügers Arch. 1999;437:617–623. doi: 10.1007/s004240050825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vovenko E, Golub A, Pittman R. Microvascular PO2 and blood velocity measurements in rat brain cortex during hemodilution with a plasma expander (Hespan) and a hemoglobin-based oxygen carrier (DCLHb) Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;540:215–220. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-6125-2_30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vreman HJ, Gillman MJ, Downum KR, Stevenson DK. In vitro generation of carbon monoxide from organic molecules and synthetic metalloporphyrins mediated by light. Dev Pharmacol Ther. 1990;15:112–124. doi: 10.1159/000457630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.White KA, Marletta MA. Nitric oxide synthase is a cytochrome P-450 type hemoprotein. Biochemistry. 1992;31:6627–6631. doi: 10.1021/bi00144a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Winslow RM. Current status of blood substitute research: towards a new paradigm. J Intern Med. 2003;253:508–517. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu L, Cao K, Lu Y, Wang R. Different mechanisms underlying the stimulation of KCa channels by nitric oxide and carbon monoxide. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:691–700. doi: 10.1172/JCI15316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xu HL, Feinstein DL, Santizo RA, Koenig HM, Pelligrino DA. Agonist-specific differences in mechanisms mediating eNOS-dependent pial arteriolar dilation in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H237–H243. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2002.282.1.H237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.You J, Johnson TD, Childres WF, Bryan RM., Jr Endothelial-mediated dilations of rat middle cerebral arteries by ATP and ADP. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1997;273:H1472–H1477. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.3.H1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zakhary R, Gaine SP, Dinerman JL, Ruat M, Flavahan NA, Snyder SH. Heme oxygenase 2: endothelial and neuronal localization and role in endothelium-dependent relaxation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:795–798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]