Abstract

Background

Communication with patients on end-of-life decisions is a delicate topic for which there is little guidance.

Aim

To describe the development of a guideline for GPs on end-of-life communication with patients who wish to die at home, in a context where patient autonomy and euthanasia are legally regulated.

Design of study

A three-phase process (generation, elaboration and validation). In the generation phase, literature findings were structured and then prioritised in a focus group with GPs of a palliative care consultation network. In the elaboration phase, qualitative data on patients' and caregivers' perspectives were gathered through a focus group with next-of-kin, in-depth interviews with terminal patients, and four quality circle sessions with representatives of all constituencies. In the validation phase, the acceptability of the draft guideline was reviewed in bipolar focus groups (GPs–nurses and GPs–specialists). Finally, comments were solicited from experts by mail.

Setting

Primary home care in Belgium.

Subjects

Participants in this study were terminal patients (n = 17), next-of-kin of terminal patients (n = 17), GPs (n = 25), specialists (n = 3), nurses (n = 8), other caregivers (n = 2) and experts (n = 41).

Results

Caregivers and patients expressed a need for a comprehensive guideline on communication in end-of-life decisions. Four major communication themes were prioritised: truth telling; exploration of the patient's wishes regarding the end of life; dealing with disproportionate interventions; and dealing with requests for euthanasia in the terminal phase of life. Additional themes required special attention in the guideline: continuity of care by the GP; communication on forgoing food and fluid; and technical aspects of euthanasia.

Conclusion

It was feasible to develop a guideline by combining the three cornerstones of evidence-based medicine: literature search, patient values and professional experience.

Keywords: communication, euthanasia, palliative care, practice guidelines, terminal care

INTRODUCTION

For several decades medical care at the end of life has been under debate. Medical end-of-life care is aimed at improving the quality of the last or terminal stage in life, and may, as such, involve end-of-life decisions which may hasten the moment of death. Such decisions in principle include the following types of decisions:

decisions about whether or not to withhold or withdraw potentially life-prolonging treatment, for example, mechanical ventilation, tube-feeding, dialysis;

decisions about the alleviation of pain or other symptoms with, for example opioids, benzodiazepines or barbiturates in dosages large enough to hasten death as a possible or certain side effect; and

decisions to administer drugs with the explicit intention of hastening death: such decisions are understood to be euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide if they are made at the patient's explicit request.1,2

Euthanasia is, under specific circumstances, legally possible only in Belgium and the Netherlands, while physician-assisted suicide is legally regulated in the Netherlands and Oregon. In Switzerland, assisted suicide is not a criminal act if it is motivated by altruistic considerations. In some countries, such as the UK, a bill on assisted dying is now in preparation. However, even in countries where euthanasia is illegal, some physicians practise it, and a growing majority of the general public is in favour of legalisation.2–5

Belgium legalised and regulated euthanasia (the administration of lethal drugs by a physician at the patient's explicit request) in May 2002. In August of the same year, the Belgian Parliament adopted a law on patients' rights, which included the right to be clearly informed and the right to self-determination. This had far-reaching implications for the physician–patient relationship. Thus, a complete change of the legal framework surrounding end-of-life decisions occurred in this country. In Belgium, contrary to the Netherlands, the adoption of the euthanasia law was not preceded by a long preparation period with an explicit tolerance policy in the courts of law, intense intra- and interdisciplinary debate, and the development of professional guidelines.6 Practical experience with the technical and communicative aspects of euthanasia was limited, both among specialists and GPs.7

To cope with a flood of individual questions from physicians regarding practical aspects of euthanasia, an organisation for palliative and terminal care set up a counselling service (LEIFartsen), which includes bedside consultation and a telephone service. Over 200 physicians are trained as end-of-life consultants to provide their colleagues with practical advice on end-of-life decisions. Therefore, coherent guidelines for these consultants and GPs were urgently needed.

We decided to limit the scope of the guideline to communication about end-of-life decisions between GPs and patients wishing to die at home (non-institutional primary care). Our motivation was triple. Firstly, we wanted to support GPs in their desire to remain the patients' partner till the end of the patients' lives, and to enhance the quality of their terminal care. All too frequently, the contact between patient and GP is lost when solutions for problems of imminent death are sought by technical and institutionalised approaches. Secondly, we wanted to support the wish of an overwhelming majority of terminally ill patients to die at home.8–10 In Belgium, only a quarter of all patients die at home; another quarter die in a nursing home, and one half in a hospital.1,8 Sometimes there is a compelling medical reason for terminal hospitalisation, but often the lack of adherence to the wish of the patient to die at home can be attributed to poorly organised palliative care in the community, insufficient support for informal caregivers to sustain care in the home, and lack of technical competence in (and sometimes avoidance of) ethical end-of-life decisions among GPs.11,12 Thirdly, since patients and caregivers do not always agree on priorities in palliative care,13 we wanted to assure the direct inclusion into the guideline of the patient perspective and wishes, in contrast to most current clinical guidelines in clinical care, which are predominately expert based. In this paper, we report on the development process of this comprehensive, evidence-based communication guideline.14

How this fits in

Implementation of patients' rights concerning the delicate topic of end-of-life decisions with possible or certain life-shortening effect requires better communication. Previous end-of-life communication guidelines do not usually include euthanasia and the voice of the patients is, at best, a secondary (expert groups) or a tertiary (literature) input in these guidelines. It was feasible to develop an evidence-based guideline that covers the whole spectrum of end-of-life decisions, based on a triangulation of literature review, patient values and professional experience.

METHOD

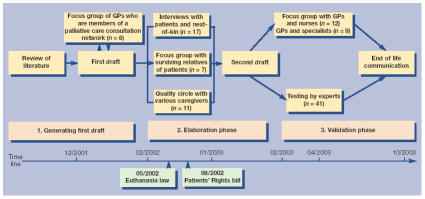

A multidisciplinary team (anthropologist, GP, oncologist, lawyer, dietician, ethicist and medical sociologist) developed the guideline in a three-phase process (generation, elaboration and validation) (Figure 1). In the generation phase, a literature search was performed in PubMed for qualitative and quantitative studies on communication in end-of-life decisions, using the following search profile: (‘terminal care’[MeSH] OR ‘life support care’[MeSH] OR ‘resuscitation orders’[MeSH] OR ‘palliative care’[MeSH] OR ‘ethics, medical’[MeSH:NOEXP] OR ‘medical futility’[MeSH] OR ‘advance care planning’[MeSH] OR euthanasia'[MeSH]) AND (‘motivation’[MeSH] OR ‘decision making’[MeSH] OR ‘communication’[MeSH]) limited to publications after 1997 and the publication type (clinical trials, reviews, practice guidelines, meta-analysis). The abstracts of the resulting 594 references were screened for relevance in primary care. In addition, the internet was searched for published and updated guidelines in palliative and terminal care, and the reference lists of relevant articles and web publications were scanned. This resulted in 224 articles of which the full text was scored between 1 to 5 according to the relevance to communication in end-of-life decisions and potential practice recommendations. Criteria that were taken into account were the setting of the study (for example, outpatients), and whether it was a guideline or not. Fifteen references were given the highest score of relevance, and another 60 were considered as ‘very relevant’ and read thoroughly by all members of the research team.

Figure 1.

Method used for the end-of-life communication guideline.

Based on these sources, an evolving semantic framework, that is, a structured collection of themes considered useful for the guideline, was used to order the excerpts from the literature. This collage of excerpts was then submitted as a first draft of the guideline to a focus group of practising GPs who received extra training on palliative and terminal care and who were, as active members of one regional palliative care consultation network, giving telephonic advice to their GP colleagues. Participants were asked to select the most important issues and to comment on the possible structure of the future guideline.

In the ensuing elaboration phase, a focus group with the next-of-kin of recently deceased patients was organised, focusing on experiences of communication between patients and caregivers. A quality circle (four consecutive discussion sessions with a heterogeneous group) was organised,15 focusing on problems in interprofessional communication in terminal care at home. In-depth interviews were conducted with terminal patients who wished to die at home. After 3 months, a second interview was organised with surviving patients and/or their next-of-kin. All interviews were audiotaped and fully transcribed.

Participants in the second phase of the study were mainly recruited with the help of the staff members of four of the 15 Flemish palliative care centres (covering 38.4% of the population) and oncology specialists. With this kind of purposive sampling,16 we tried to have a balanced male and female participation and heterogeneity (not necessarily representativity) regarding disease, socioeconomic status, life stance, age and region.

Analysis was based on grounded theory and included a process of iterant coding of emerging themes and constant comparison.17 To ensure inter-encoder reliability, data were analysed independently by two authors and an external person. The findings of the qualitative study were used to integrate the experiences of patients, next-of-kin and caregivers, in order to develop a second draft of the guideline.

In the third and final validation phase, the draft guideline was submitted to one focus group of GPs and nurses, and to one focus group of GPs and specialists. Participants of the focus groups of the third phase were recruited through personal contacts with informants in the field. The draft was also reviewed by end-of-life experts (lawyers, ethicists and oncologists), who were asked to comment on the suitability of the guideline for implementation and its acceptability. The written comments of these experts were centrally collected, analysed and integrated into the third and final version of the guideline (Figure 1).18

RESULTS

In the generation phase, eight GPs participated in the first focus group (Table 1). In the elaboration phase, seven next-of-kin of recently deceased patients took part in focus group 2. The quality circle consisted of five GPs, two nurses, two next-of-kin, one volunteer palliative caregiver and one psychologist. Seventeen terminally ill patients who wished to die at home were interviewed, of whom eight were interviewed together with the next-of-kin. In 11 cases it was possible to have a second interview, twice with the patient and relative, four times with the patient only, and five times only with the relative who had participated in the first interview.

Table 1.

Participants in the acquisition of qualitative data.

| Phase | Method | Patients | Relatives/next-of-kin | GPs | Specialists | Nurses | Other caregivers | Experts | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generation | Focus group 1 | 8a | 8 | ||||||

| Elaboration | Interviews | 17 | 8 | 25 | |||||

| Focus group 2 | 7 | 7 | |||||||

| Quality circle | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 11 | ||||

| Validation | Focus group 3 | 6 | 6 | 12 | |||||

| Focus group 4 | 6 | 3 | 9 | ||||||

| Testing by experts | 41 | 41 | |||||||

| Total | 17 | 17 | 25 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 41 | 113 | |

All these GPs belong to a palliative care consultation network.

In the validation phase, six GPs and six nurses participated in the third focus group and another six GPs and three specialists (two oncologists and a haematologist) took part in focus group 4. Finally, 24 medical experts and 17 other experts (lawyers and ethicists) sent written comments on the guideline.

In the generation phase of the project, the focus group of GPs experienced in counselling other GPs in palliative care (palliative care consultants) prioritised four themes: first, truth telling on diagnosis, prognosis and the inevitability of imminent death; second, exploration of the patients' wishes regarding the end of their life; third, communication on disproportionate interventions for patients with a poor prognosis; and finally dealing with requests for euthanasia in the terminal phase of life.

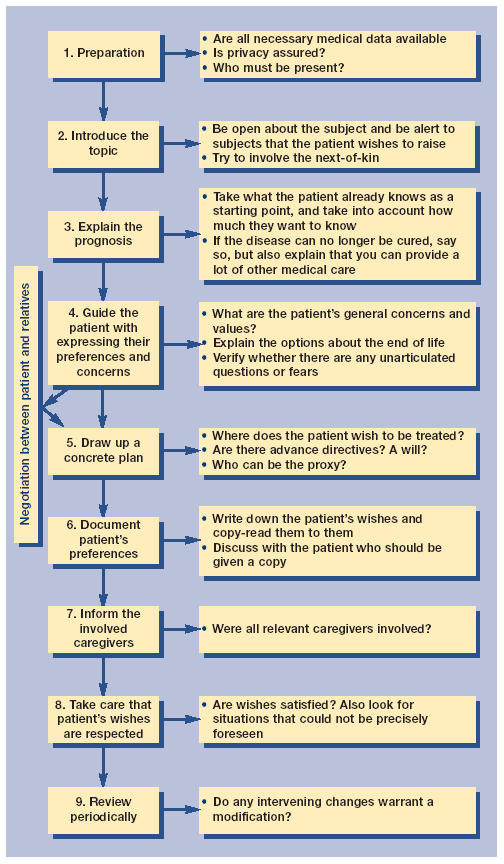

In addition, the participating GPs provided the research team with recommendations for a template to be used for each of the four themes in a step-by-step workflow, aimed at providing maximum clarity and carefulness regarding communication about end-of-life decisions. Each theme is formatted accordingly, starting with a clear context setting (definitions, statement of objectives, delineation of the role of the GP, legal and deontological framework). The palliative consultants then suggested providing a concise listing of practical recommendations, frequent pitfalls, prerequisites to be met, and two checklists (one dealing with carefulness in the pursuit of optimal quality in patient care, and one dealing with the carefulness in the respect of legal issues). Finally, it was recommended to end each of the four main themes with a graphic recapitulative flowchart (see Figure 2 for an example).

Figure 2.

Example of a flowchart: exploration of patients' wishes regarding the end of life.

In the elaboration phase, the participants in the qualitative study (both patients and caregivers) expressed a need for guidance in communication on end-of-life decisions. The priority of the four main themes was confirmed, with the identification of key problems and recommendations. Box 1 shows an example of one of the themes in more detail.

Box 1. Dealing with a request for euthanasia.

-

▸

The fourth theme on dealing with a request for euthanasia was of special importance for the Belgian GPs, because it dealt with an unprecedented situation by which euthanasia became a legal option. GPs stated that such requests from terminal patients are emotionally, as well as practically, difficult to deal with. A prerequisite for dealing with implicit or explicit requests for euthanasia is to be sure of patients' good understanding of the diagnosis and prognosis. If necessary, truth telling should be repeated. Patients' motivations, wishes and values should be thoroughly explored. The full range of other possible end-of-life decisions, including intensified pain and symptom alleviation and non-treatment decisions, should be discussed. Once these prerequisites are met, the process of shared decision making can be started.

-

▸

The clinical guideline on dealing with requests for euthanasia outlines this process in 11 steps. These include clarifying the patient's request, consultation with other caregivers, making formal arrangements with the patient, aspects of technical preparations (for example, choices and dosages of drugs used for euthanasia), and aftercare of next-of-kin and all the involved caregivers. Whether the patient, after due consideration of alternatives, still prefers euthanasia is to be ascertained iteratively during the process.

Also, three additional themes were identified for special attention: expectations of patients for the GP to play a central and active role in assuring continuity of care in the dying process; the importance of communication on food and fluid administration in home care; and the difficulties with communicating technical aspects of the use of lethal drugs in euthanasia. All these elements were integrated by the research team in the draft guideline.

In the third validation phase, caregivers and experts provided useful corrections to the drafted guideline. The explicit confirmation by the experts of the guideline's suitability for implementation and its acceptability allowed the research team to finalise it.

The final guideline was the result of the integration of the findings in the literature, early feedback from expert practitioners in the field, qualitative research among major constituencies in communication and decision processes in home care for the terminally ill, and validation in focus groups targeted on the evaluation of the feasibility to implement the guideline, supplemented with a final content review by a multidisciplinary team of experts, including a legal expert.

The guideline also includes several obstacles and pitfalls as identified by the participating patients and caregivers. Examples of frequently encountered obstacles are the inhibitions of both patients and professionals to overtly discuss preferences on how to die, and the ambivalence of words such as ‘euthanasia’. Pitfalls that were pointed out are last-minute moral qualms of physicians who have made promises of assistance too hastily on previous occasions; postponing the discussion of the patient's preferences until they are unable to express their will; losing contact with the patient because of misunderstandings on the expected frequency of encounters or poor communication with specialists; psychological difficulties in dealing with fluid and food administration to terminally ill patients; poor exploration of the attitudes towards futile treatment with the patient and with the family. A common pitfall is the last minute hospitalisation in the ultimate terminal phase, to be avoided by a specific anticipating discussion with all involved.

The guideline is distributed in print as a structured book (in Dutch) of 239 pages.14

DISCUSSION

GPs experience uncertainty on how to inform patients about their inevitable death and how to explore their preferences regarding how to die, despite — or maybe because of — the new laws on euthanasia and patient autonomy. Both experiences and research on this topic are scarce. Therefore GPs are in need of a comprehensive guideline on how to deal with this new situation. It was feasible to develop a guideline on end-of-life decisions that is not only based on experts' opinions but also includes opinions of the caregivers and patients whom it is meant for.

The making of this present guideline was driven by a triangulation of literature review, medical experience of caregivers, and perceptions of patients and their relatives. Hence, the three cornerstones of a more recent definition of evidence-based medicine were incorporated.19 Furthermore, this end-of-life communication guideline is consistent with two fundamental legal changes in Belgium (the legalisation of euthanasia and the bill of patients' rights).

To enable implementation in other settings or countries, further validation is necessary. However, since the guideline deals with practices, questions and problems that physicians are confronted with in all countries, it might be relevant for physicians in different settings and countries, by pointing out frequent obstacles and pitfalls and offering concrete suggestions for better care in end-of-life decisions.

There exist several guidelines on end-of-life decisions, however, most of these are restricted to specific medical decisions (for example, resuscitation and life-sustaining treatments), or specific types of patients (such as those with lung cancer and neonates) and are rarely applicable for home care.20,21 Furthermore, they were mainly driven by expert consensus only, without active involvement of patients and their relatives.21–23 This guideline aims to put difficult issues such as euthanasia into the broader context of integrated terminal care in which all possible end-of-life decisions should be considered and attuned to one another.

Due to this integrated approach of a complex topic such as end-of-life decisions, the final guide resulted in a comprehensive document of 239 pages (including appendices) that provides both a general overview and detailed practice recommendations. As such, it can be used as a teaching aid in palliative and terminal care. Since not all GPs have the time to read the book as a whole, it is also intended for use as a quick reference book to look up questions that GPs are frequently confronted with. Therefore, chapters have fixed subsections according the suggestions of participating GPs (for example, a summarising flowchart, checklists and pitfalls), and the text includes 30 frames dealing with problems frequently encountered in daily practice.

Implementation research is necessary to determine whether this guideline will contribute to reducing uncertainty in communication between caregivers and terminally ill patients, and to promote the respect of patients' wishes to die at home.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank all patients, relatives, caregivers and experts who contributed to this work. Claudia Torrico served as an external reviewer for the qualitative data analysis. Lieve Van den Block coordinated the expert validation process. Leo Schillemans coordinated the quality circle. Lucas Ceulemans coordinated the cooperation with the Scientific Society of Flemish General Practitioners.

Funding body

The study was funded by the Belgian Science Policy (Project No. SO/02/022) and the Research Council of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (Project No. HOA2)

Ethics committee

The Ethical Committee of the Ghent University approved the study (2002/098)

Competing interests

The authors have stated that there are none

REFERENCES

- 1.Deliens L, Mortier F, Bilsen J, et al. End-of-life decisions in medical practice in Flanders, Belgium: a nationwide survey. Lancet. 2000;356:1806–1811. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03233-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van der Heide A, Deliens L, Faisst K, et al. End-of-life decision-making in six European countries: descriptive study. Lancet. 2003;362:345–350. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helou A, Wende A, Hecke T, Rohrmann S, Buser K, Dierks ML. Public opinion on active euthanasia. The results of a pilot project [German] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2000;125:308–315. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1024146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Neill C, Feenan D, Hughes C, McAlister DA. Physician and family assisted suicide: results from a study of public attitudes in Britain. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:721–731. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00421-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hurst SA, Mauron A. Assisted suicide and euthanasia in Switzerland: allowing a role for non-physicians. BMJ. 2003;326:271–273. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7383.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deliens L, van der Wal G. The euthanasia law in Belgium and the Netherlands. Lancet. 2003;362:1239–1240. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14520-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vander Stichele RH, Bilsen JJ, Bernheim JL, et al. Drugs used for euthanasia in Flanders, Belgium. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2004;13:89–95. doi: 10.1002/pds.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hays JC, Galanos AN, Palmer TA, et al. Preference for place of death in a continuing care retirement community. Gerontologist. 2001;41:123–128. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang ST, Mccorkle R. Determinants of congruence between the preferred and actual place of death for terminally ill cancer patients. J Palliat Care. 2003;19:230–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grande GE, Farquhar MC, Barclay SI, Todd CJ. Valued aspects of primary palliative care: content analysis of bereaved carers' descriptions. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:772–778. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang ST, Mccorkle R. Determinants of place of death for terminal cancer patients. Cancer Invest. 2001;19:165–180. doi: 10.1081/cnv-100000151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van den Eynden B, Hermann I, Schrijvers D, et al. Factors determining the place of palliative care and death of cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2000;8:59–64. doi: 10.1007/s005209900094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ewing G, Rogers M, Barclay S, et al. Palliative care in primary care: a study to determine whether patients and professionals agree on symptoms. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56:27–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deschepper R, Vander Stichele RH, Mortier F, Deliens L. Carefully dying at home: a guideline for general practitioners [Zorgzaam thuis sterven: een zoegleidraad voor huisartsen] Gent: Academia Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schillemans L, Remmen R, Maes R, Grol R. Quality circles in primary health care: possibilities and applications. In: Chan CFL, editor. Quality and its applications. First Newcastle International Conference on Quality and its Applications; 1–3 September 1993; Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom. Newcastle: Newcastle Quality Centre, Faculty of Engineering; 1993. pp. 393–398. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernard HR. Research methods in anthropology: qualitative and quantitative approaches. 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks, Ca.: Altamira Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks, Ca.: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deschepper R, Vander Stichele R, Mortier F, Deliens L. Quality communication about end-of-life decisions in competent patients who wish to die at home. Guidelines for general practitioners. Final report for ex post evaluation of the project ‘Medical and ethical quality care when taking end-of-life decisions: development of a protocol for first-line health-care.’. http://users.pandora.be/scancode/vub/zl3%20summary.PDF (accessed 22 Nov 2005)

- 19.Sackett DL, Straus SE, Richardson WS, et al. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Griffin JP, Nelson JE, Koch KA, et al. End-of-life care in patients with lung cancer. Chest. 2003;123(1 Suppl):312S–331S. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.1_suppl.312s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lo B, Quill T, Tulsky J. Discussing palliative care with patients. ACP-ASIM End-of-Life Care Consensus Panel. American College of Physicians — American Society of Internal Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:744–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balaban RB. A physician's guide to talking about end-of-life care. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:195–200. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.07228.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gastmans C, Van Neste F, Schotsmans P. Facing requests for euthanasia: a clinical practice guideline. J Med Ethics. 2004;30:212–217. doi: 10.1136/jme.2003.005082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]