Abstract

BACKGROUND

Federal laws and regulations, including the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996, intended primarily to protect individuals, have been described as significant barriers to the use of clinical registries and other population-based tools for health care research. Although these regulations allow for the waiver or alteration of usual consent procedures when the research meets certain specific criteria, waivers and alterations are rarely used in health care research.

METHODS

The Vermont Diabetes Information System is a multistate randomized trial of a quality improvement intervention that uses a novel alteration of informed consent to help ensure that the study sample is representative of the target population. Patients are notified by mail that they are eligible for the study and that they may opt out of the study, if they desire, by calling a toll-free number.

RESULTS

Seven thousand five hundred and fifty-eight patients were invited to participate. Two hundred and ten (2.8%) opted out. Three patients (0.04%) filed complaints, all of which were addressed satisfactorily.

CONCLUSIONS

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and other federal regulations raise challenges to the use of clinical registries in research, but modifications to the consent process, including passive consent methods, are useful tools to overcome these challenges. It is possible to recruit a broad and representative population under current law while maintaining appropriate protections for research subjects.

Keywords: ethics, research, informed consent, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, confidentiality, privacy

Clinical research requires trade-offs between the rights of subjects and the benefits to populations of the knowledge gained. For many years, informed consent has been the cornerstone of clinical research ethics and the approach to this trade-off. Federal regulations governing consent for human research in the United States have 3 main components: The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 (Public Law 75-717), which covers certain research activities regulated by the Food and Drug Administration; the “Common Rule,” adopted in 1991 by 16 federal agencies (U.S. Code of Federal Regulations 45CFR Part 46, among others), which governs the activities of most other federally supported medical researchers and provides for Institutional Review Boards (IRBs); and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996 (Public Law 104-191, 45CFR Parts 160 and 164), which governs confidentiality of personal information in health care, including research.

These 3 laws share a common foundation in the concept of informed consent. In general, they require that participants provide their active and fully informed consent. They also prohibit the transfer of identifiable health information such as names, diagnoses, and test results to researchers without the patient's consent. The elements of informed consent are described in the common rule. Section 46.117 requires that consent “be documented by the use of a written consent form approved by the IRB and signed by the subject or the subject's legally authorized representative.”

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act broadened the protection of human subjects to all research conducted by a covered entity such as a physician, hospital, or health plan, regardless of funding. It uses the same language found in the common rule to describe informed consent. Both HIPAA and the common rule allow for a waiver or alteration of the consent process at the discretion of the IRB under certain circumstances. “An IRB may approve a consent procedure which does not include, or which alters, some or all of the elements of informed consent set forth in this section, or waive the requirements to obtain informed consent provided the IRB finds and documents that:

the research involves no more than minimal risk to the subjects;

the waiver or alteration will not adversely affect the rights and welfare of the subjects;

the research could not practicably be carried out without the waiver or alteration; and

whenever appropriate, the subjects will be provided with additional pertinent information after participation.” (45CFR 46.116(d))

If these circumstances are met, the IRB may authorize an alteration or omission of parts of the consent process, or even allow the study to proceed without any consent process.

Before their implementation, many observers expressed concern that these rules, especially the HIPAA regulations, would have a chilling effect on health research.1 For instance, the Vice President of the American Association of Medical Colleges wrote that the regulations pose “serious and ill-advised obstacles to the conduct of clinical studies.”2 Some noted that IRBs seem reluctant to use the waiver provisions3 and that the use of waivers and other aspects of informed consent vary widely from board to board.4,5

Since the implementation of HIPAA, empirical data on the impact of HIPAA have begun to appear. Researchers in Wisconsin documented a reduction in the number of proposed medical record and database research projects.6 Before HIPAA, 89% of such proposals were approved and all went through an expedited process. By 2002, approval without revision dropped to 59%. Investigators in Michigan using a coronary syndrome registry documented a decline in permission for follow-up from 96% to 34% after HIPPA.7

A recent report from Canada further detailed the difficulties and costs (both financial and scientific) of requiring a full consent process in low-risk research.8 Despite aggressive recruitment, only about half of eligible patients could be enrolled. The barrier of the burdensome consent process rendered this critically needed data set largely useless. European experience with consent for registries has also been problematic.9

In this legal and research environment, we sought to develop a clinical registry as part of a quality improvement research project. To balance the rights of potential subjects against the need for a broad and representative population, we used little-known consent procedures authorized by HIPAA and other federal regulations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Vermont Diabetes Information System (VDIS)

Vermont Diabetes Information System is a novel clinical intervention that is meant to improve the quality of diabetes care in primary care settings.10 Its goals are to operationalize and disseminate certain aspects of the Chronic Care Model.11,12 Vermont Diabetes Information System receives daily reports from participating laboratories containing the results of diabetes studies (serum A1C, serum lipids, serum creatinine, and urine microalbumin to creatinine ratio) recommended by local and national guidelines.13,14 These data are reformatted and communicated to both providers and patients in 5 ways: (1) providers receive faxed flow sheets of test results and recommendations for further action after any new result; (2) patients receive letters recommending they discuss their diabetes care plan with their provider after reports of very elevated A1C or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; (3) providers receive faxed reminders whenever a patient is overdue for a recommended test; (4) patients receive reminders by mail when they are overdue for testing; and (5) providers receive quarterly lists of all their diabetic patients sorted by the level of control. These population reports also include rates of treatment success and timeliness for the provider and some comparison groups as benchmarks.

To evaluate VDIS, we have implemented a large, multicenter, randomized clinical trial. Primary care practices that use any of 13 laboratories in Vermont, New York, or New Hampshire were invited to participate. The practices were randomly assigned to either “active” or “control” status. Active practices receive all 5 services described above. Control practices receive none.

After a provider agreed to participate, a HIPAA-compliant business agreement was signed by the practice, the university, and the overseeing peer review organization, the Vermont Program for Quality in Health Care (VPQHC). It states that the practice, the investigators, and VPQHC are providing a system that improves the delivery and interpretation of clinical information from the laboratory to the practice and patient. The laboratory was then queried for the patient name and result for all A1C tests that the provider had ordered on any adult in the previous 2 years. This list was sent to the provider who removed any subject who was not diabetic or not under the care of that provider. The remaining patients were enrolled in the study unless they opted out as described below.

The main study plan calls for the comparison of laboratory results and timeliness between the active and control groups with adjustments for clustering and other factors.10 The results will be available in the year 2006. The evaluation also includes a substudy of nonlaboratory factors such as blood pressure, functional status, and medications. Random samples of patients from each practice are invited by telephone to participate in a survey that includes a questionnaire and measurement of height, weight, and blood pressure. Substudy participants complete a traditional informed consent process with a research assistant and sign a consent form. The introduction to the substudy is included in the initial passive consent letter.

Passive Consent Process

The various IRBs that reviewed the proposal agreed that it met the 4 criteria for a waiver of informed consent under the law. However, there were other, extra-legal, factors that argued against an entirely invisible process of patient identification and enrollment. The clinicians and the laboratories owned by community hospitals were worried about public concern as patients discovered they were enrolled without consent into a research project. It was the research aspect of the system, rather than the intervention itself, which increased the perception of risk.

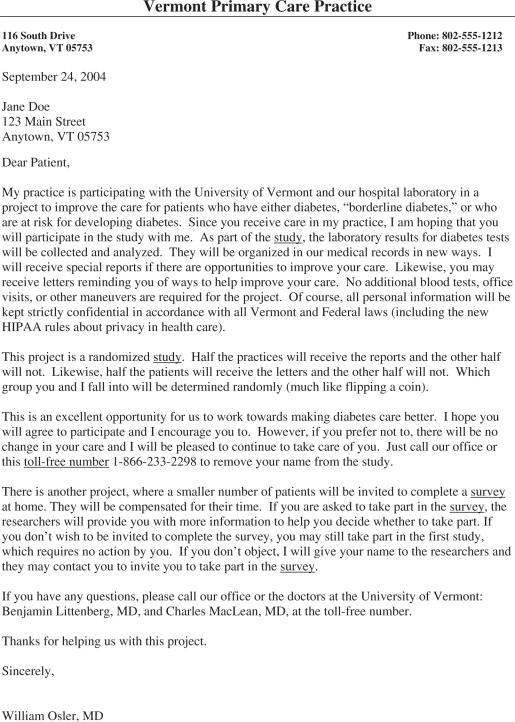

To address these community relations concerns, the investigators designed a passive consent or “opt-out” process. Before enrollment, VDIS sent a letter on behalf of the provider to each eligible subject (see Fig. 1). The letter outlined much of what is usually seen in a consent document: the reasons for the study, the procedures to be followed, the risks and benefits of participating, and assurances that confidentiality will be maintained and that usual care will proceed even if the subject opts not to participate. Subjects who wish to withdraw were asked to call their provider or a toll-free number provided in the letter. Ten business days after mailing the letters, we turned on the system for all patients who had not refused. Patients may request at any time to be withdrawn from the study. Although opt-out processes have been used in other countries,15 we are aware of only 1 previous use in the United States.16

FIGURE 1.

The passive consent letter.

VDIS and Federal Regulations

The VDIS proposal was reviewed by a number of IRBs and attorneys from the university, the state-wide peer review organization, and several of the participating hospital laboratories. In each case, the initial reaction was concern that a trial could not proceed without active, written, signed consent. However, after much discussion and deliberation, and education about federal law, all agreed that the study met all 4 of the criteria for a waiver or alteration of consent required by the Common Rule and HIPAA.

The Research Involves no More than Minimal Risk to the Subjects.

Because there is no invasive intervention, VDIS poses only minimal risk. The risks to patient privacy and confidentiality were addressed by rigorous application of good data management and security protocols, including the removal of identifiers from the research data set used by the analysis team, locked cabinets for physical data, and firewalls and password security for all electronic data files.

The Waiver or Alteration will not Adversely Affect the Rights and Welfare of the Subjects.

The IRBs found that subjects have ample opportunity to withdraw from the study and that their welfare was unlikely to be damaged in those cases.

The Research Could not Practicably be Carried out Without the Waiver or Alteration.

Many reviewers suggested that we obtain written consent at the time of the patient's visit. We argued that this would have required a huge and expensive infrastructure to provide full-time coverage at all the many sites (offices, home care, hospitals, emergency rooms, etc.) where specimens are collected. Others suggested that we send a consent form to each participant as they are identified and enroll only those who return a signed document. We noted that the participation rate would undoubtedly be very low and that the loss of generalizability would be particularly harmful to the study. One of the goals of VDIS is to engage those subjects who are lost (or becoming lost) to follow-up. These are the very subjects least likely to return consent paperwork. This last argument was most persuasive to the UVM IRB. They accepted the concept that quality improvement or public health research aims to address the care of everyone, including those who may have left the confines of the health care system (the disenfranchised, the noncommunicative, and the lost-to-follow-up, among others). These “outsiders” cannot be studied if we require that all subjects must first be in the system (at least long enough to sign consent forms). In other words, it is not merely difficult or expensive to study these populations if active consent is required, it is essentially impossible (impracticable).

Subjects will be Provided with Additional Pertinent Information.

This criterion is a response to the notorious Tuskegee study and other research in which the investigators withheld important clinical information from the subjects.17 In VDIS, everything that is known about the patients (including both active and control subjects) is already communicated to the providers and patients through the usual mechanisms of laboratory reporting.

Provider Protections

One hazard of creating a registry is that the data may identify providers who appear to have low quality of care. If this becomes public, it could be used to support a malpractice claim or otherwise embarrass or disadvantage the provider. The threat of a data release may dissuade providers from participating. Therefore, each participating provider is appointed to a peer review committee under the auspices of VPQHC, a state-wide peer review organization. The Medical Director of VPQHC, the Principal Investigator, and the Project Director constitute the executive committee of the peer review committee, and meet periodically. Similar to the protections enjoyed by hospital quality improvement committees, Vermont state law (Vermont 26 V.S.A. Sec 144 et seq.) protects the findings and deliberations of such committees from legal discovery. Because, in some sense, the providers are also research subjects who face certain risks distinct from those facing patients, each provider completed a written consent process and signed a consent document.

RESULTS

Subject Participation and Refusal

Vermont Diabetes Information System currently comprises 13 laboratories, 72 practices, 151 providers, and 7,348 patients. In the first 14 months of operation, we identified 7,558 eligible subjects and mailed passive consent letters to each of them. Two hundred and ten recipients requested withdrawal for a refusal rate of 2.8%. The reasons for refusal included “not interested” (129), “too ill” or “too old”(14), “privacy concerns”(3), “too busy”(3), and “too much travel (1).” Sixty respondents gave no reason for refusal.

Three potential subjects (0.04%) complained about the consent process. No complaints have progressed to the point of a legal action. All have been discussed by the Data Safety Monitoring Board and the IRB. In some cases, these complaints prompted changes to the study protocol.

Case #1.

This subject called 6 weeks after we sent the passive consent letter to his post office box. This is the address the laboratory uses for billing or other issues. It receives mail both for his home and business. His secretary opened the letter and may have learned that he has diabetes. He did not request withdrawal at that time. He received no other contacts from the system until we called him and left a message inviting him to participate in the substudy.

He was upset that we had a left a message on his answering machine with information that identified him as having diabetes. He also had concerns that the original letter was not marked “Personal and Confidential.”

He was invited to attend a meeting of the IRB for a full discussion, but did not appear. We changed the calling protocol on answering machines. Schedulers were trained to say only “I'm calling about the letter recently sent to you from your doctor's office. Please call me back, toll free, at 866-233-2298.” We also began to mark all correspondence to subjects with “Personal and Confidential” on the envelope.

Case #2.

A participating hospital received a complaint from a man who was upset that they had released his data when paragraph 2 of the passive consent letter seemed to suggest that that would not happen.

The Principal Investigator spoke with the hospital's compliance officer and explained that paragraph 2 actually referred to the substudy, not the main diabetes registry. The compliance officer agreed that there was no violation. The passive consent letter was rewritten to clarify the differences between the main study and the substudy. The revised letter appears in Figure 1.

Case #3.

This subject was away from home for several weeks. When she returned, she found both the passive consent letter and the first VDIS report (she was overdue for a recommended laboratory test). She was knowledgeable about HIPPA and insisted that this was a violation of the regulations.

An investigator spoke with her and explained the consent provisions in HIPPA. We mailed her a photocopy of the relevant passages from the regulations (section 164.512 (i) of the CFR) and removed her from the study. She had no further complaints.

DISCUSSION

Current law allows for the transfer and manipulation of personal health information for clinical uses. There are no legal barriers to providers authorizing the release of laboratory data to a registry such as VDIS for the purposes of participating in the patient's care. The reports that VDIS produces for providers and patients are, in this regard, similar to standard laboratory reports sent to ordering providers, or the reports of mammograms routinely sent to patients who have been screened for breast cancer.

However, for research, subjects generally must provide informed consent.18 In our experience, many investigators (and IRBs) believe that this is an absolute restriction. This belief may have slowed the use of registries to improve care. Nonetheless, the laws allow for alterations to the consent process. These provisions strike a delicate balance between the individual's right to privacy and autonomy and the public health needs of the community. Federal laws are not as much a hindrance to population-based research as is often suggested. In the case of VDIS, careful use of an altered consent procedure produced a study sample comprising over 97% of the target population. Such a high rate is virtually unknown in studies that require an active or “opt-in” consent procedure and allows VDIS to avoid substantial sample selection biases that have plagued other efforts.

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and other federal regulations raise challenges to the use of clinical registries in research, but modifications to the consent process, including passive consent methods, can help overcome these challenges. It is possible to recruit a broad and representative population while maintaining appropriate protections for research subjects.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01 DK61167 and K24 DK068380).

REFERENCES

- 1.Wadman M. US privacy laws may curb access to medical data. Nature. 1997;386:533. doi: 10.1038/386533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kulynych J, Korn D. The new federal medical—privacy rule. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1133–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp020113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenfeld CR. Medical privacy and medical research. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1674. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200205233462118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Annas GJ. HIPAA regulation—a new era of medical-record privacy? N Engl J Med. 2003;345:1486–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMlim035027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McWilliams R, Hoover-Fong J, Hamosh A, Beck S, Beaty T, Cutting G. Problematic variation in local institutional review of a multicenter genetic epidemiology study. JAMA. 2003;290:360–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.3.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Herrin JK, Fost N, Kudsk KA. Health Insurance Portability Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations: effect on medical record research. Ann Surg. 2004;239:772–8. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000128307.98274.dc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armstrong D, Kline-Rogers E, Jani SM, et al. Potential impact of the HIPAA privacy rule on data collection in a registry of patients with acute coronary syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1125–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.10.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tu JV, Willison DJ, Silver FL, et al. Impracticability of informed consent in the registry of the Canadian stroke network. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1414–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa031697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busby A, Ritvanen A, Dolk H, et al. Survey of informed consent for registration of congenital anomalies in Europe. BMJ. 2005;331:140–1. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7509.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacLean CD, Littenberg B, Gagnon G, Reardon M, Turner PD, Jordan C. The Vermont Diabetes Information System (VDIS): study design and subject recruitment for a cluster randomized trial of a decision support system in a regional sample of primary care practices. Clin Trials. 2004;1:532–44. doi: 10.1191/1740774504cn051oa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002;288:1775–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, Part 2. JAMA. 2002;288:1909–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vermont Program for Quality in Health Care. Montpelier: VPQH; 2004. Recommendations for Management of Diabetes in Vermont. [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Diabetes Association. American diabetes association clinical practice recommendations. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(suppl 1):S1–S150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark AM, Jamieson R, Findlay IN. Registries and informed consent [letter] N Engl J Med. 2004;351:612–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200408053510621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dziak K, Anderson R, Sevick MA, Weisman CS, Levine DW, Scholle SH. Variations among Institutional Review Board reviews in a multisite health services research study. Health Serv Res. 2005;40:279–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00353.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wichman A, Sandler AL. Institutional review boards. In: Gallin JI, editor. Principles and Practice of Clinical Research. Vol. 52. San Diego: Academic Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Public Health Service. Health Services Research and the HIPAA Privacy Rule. [July 11, 2005]; Available at http://privacyruleandresearch.nih.gov/pdf/HealthServicesResearchHIPAAPrivacyRule.pdf.