Summary

This paper examines how the limited exposure of the professional dental community in the United States to the potential caries reduction benefits of xylitol, and the absence of vehicles for xylitol that could be recommended in private practice settings or applied in public health programs, has retarded xylitol’s adoption. Few papers appeared in the English language literature prior to the last two decades but now a greater number are appearing. Current work at the University of Washington has led to a series of randomized controlled trials more clearly establishing dosing and frequency guidelines and increased interest in use of xylitol products for caries prevention. Steps to develop effective alternative vehicles for the delivery of xylitol particularly useful for young children and institutional settings in America, and their bioequivalency, are explored.

Keywords: cariostatic agents, xylitol, dental caries

In the United States xylitol use for the prevention and reduction of dental caries has not taken off as it has in Finland where the effect of xylitol use in the reduction of dental caries was first realized (1). This paper examines the hypothesis that until recently the limited exposure of the professional dental community in the United States to the potential caries reduction benefits of xylitol, and the absence of vehicles for xylitol that could be recommended in private practice settings or applied in public health programs, has retarded xylitol’s adoption. The paper reviews the current work of our laboratory conducting a series of randomized controlled trials to more clearly establish the dosing and frequency basis for the use of xylitol containing products for the prevention of dental caries, and potentially acute otitis media. It outlines present and future steps in our attempts to develop effective alternative vehicles for the delivery of xylitol particularly useful for young children.

Xylitol has a forty-plus year history of use in the United States, yet it is only in the last five years that its use as a dental therapeutic agent has begun to increase substantially. Xylitol was approved for use by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as early as 1963 as a food additive. Initially its primary use was in the diets of diabetics. It has also been used in small amounts in foods labeled as “sugar-free.” Thus the use of xylitol has not been wide spread or in sufficient concentration in products in the market to effect dental caries during the first several decades of its use in the United States.

Limited Exposure in the US Professional Community

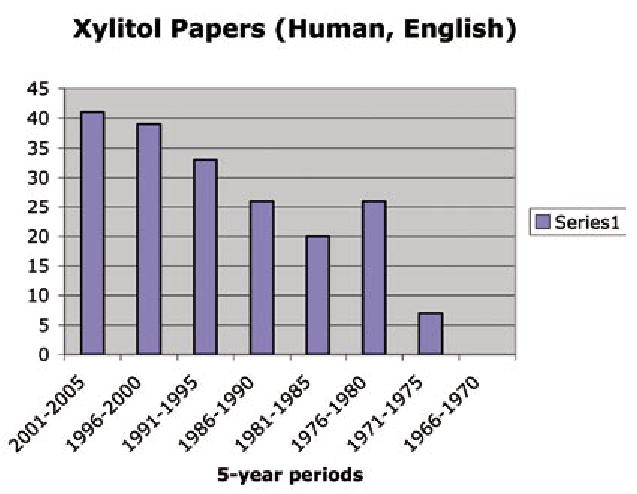

To assess the exposure of the professional dental community to the literature and research available on the potential benefits of xylitol, a search was conducted of the PubMed database to identify papers on xylitol and dental caries published in English and involving humans for the period 1965 to 2005. Figure 1 gives the result indicating a trend from 1965 to 2005 of a gradual increase in literature available to clinicians on this subject. The only exception to the trend was from 1976 to 1980 when the Turku sugar studies were published. Nevertheless, the number of papers is relatively small and might explain the modest adoption of xylitol as a preventive agent in the United States.

Figure 1.

The number of human papers on xylitol and dental caries appearing in English language journals between 1966 and 2005.

The first significant dental recommendations for the use of xylitol began to appear in the dental literature in the United States in the early 1990’s. Anderson, et al., presented the medical model approach to dental caries incorporating the use of sealants, antimicrobials, fluorides and xylitol (2). During this same period the dental products company, Henry Schein, made xylitol gum (XyliFresh, Leaf OY, Turku, Finland) available through its distribution channels (2). The Calorie Control Council published its brochure on the use of xylitol for dental caries reduction (3). Despite this priming of awareness of xylitol’s potential, its incorporation into the preventive armamentarium of dentists remained limited. Several factors have been barriers. A key barrier is the lack of availability of effective products to offer patients: the food and candy industry that produces products containing xylitol sees them as consumer products and not preventive agents. In these products xylitol has typically been used only in small amounts for its sweetness in both sugar containing items and sugar-free products. XyliFresh gum was unique in that it was 100% xylitol sweetened as it was developed with Finnish researchers to study the effect of xylitol on dental caries. However, its availability in the United States was limited to access through a dental distributor (it is no longer available through Henry Schein) and it had to be ordered and reordered as the xylitol habit has to be consistently maintained for effectiveness. The cost of the gum was significant and added to the burden of maintaining a habit.

Data breaking out demand for xylitol specifically for dental uses by year in the US over time are not publicly available but demand appears to have been low. More recently market forces have begun to change this dynamic shaped by increasing evidence for the role of xylitol in reducing the incidence of dental caries. Specialty companies are starting to produce xylitol products directed at the dental consumer and it appears demand may be outstripping supply of xylitol. Examples include gums, mints, toothpaste, and mouth rinses. Generally these are labeled such that their xylitol content can be determined and contain effective amounts. These companies are able to be successful to a limited degree through their internet marketing to health conscious consumers. The major American candy companies have noticed the recent appeal of xylitol and to take advantage of this their marketing strategy is to highlight when a product contains xylitol. These sugar-free products are directed at the general gum and candy consumer not dental consumers and professionals. As a general rule the amount of xylitol in these products is often not clearly labeled. Such labeling is not required under US law.

Xylitol Products Available in the US Marketplace

Tables 1 and 2 list xylitol vehicles widely available in the US, concentrations of xylitol and the estimated cost per day for xylitol use if the user buys the product in the consumer market. These tables are updated versions of ones we previously published as such products and costs are constantly changing (4). As can be seen, the most effective vehicles are still primarily chewing gums and the cost per day is quite high. The tables also show that many products are so poorly labeled that consumers and dentists cannot judge properly whether they should be advocated. In order to have any meaningful impact on the US caries problem, purchases will need to be made in bulk at lower unit prices and distributed at low or no cost to families in poverty. Dental caries prevalence in the US is inversely related to family income and dental care for this part of the population is severely limited.

Table 1.

Xylitol-Containing Gums and Mints Available in U.S. Markets, Their Xylitol Content, Preventive Potential, and Approximate Cost†

| PRODUCTS†† | XYLITOL per piece (g) [total polyols (g)] | PIECES FOR 6 (10) g/day | PREVENTIVE Potential††† | APPROXIMATE COST/10 pieces |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biogenesis “Xylitol Fruit Gum” | 0.72 | 8(14) | Yes | $1.30 – $1.90 online |

| Clen-Dent/Xponent Gum (various flavors) | 0.67 | 9 (15) | Yes | $0.70 – $1.30 online |

| ElimiTaste “Zapp” & “Smoke Screen” gums | 1.00 | 6 (10) | Yes | $0.70 – $1.10 online |

| Elma “MASTICgum” | 0.53 | 11 (19) | Yes | $2.25 online |

| Emerald Forest “Ricochet Xylitol Gum” | 0.72 | 8 (14) | Yes | $0.75 – $0.85 online |

| Epic – Xylitol Gum (various flavors) | 1.05 | 6 (10) | Yes | $0.70 – $1.00 online |

| Fennobon Oy “XyliMax Gum” | 0.86 | 7 (12) | Yes | $0.80 – $1.00 online |

| Hershey “Carefree Koolerz Gum” (various flavors) | 1.50 | 4 (7) | Yes | $0.95 – $1.50 retail |

| Lotte – Xylitol Gum (various flavors) | 0.65 | 9 (15) | Yes | $0.70 – $0.80 online |

| Nature’s Provision “Smart Smile Gum” (Xylipro) | 0.7 | 9 (14) | Yes | $0.65 – $0.75 online |

| Omnii “Theragum” | 0.70 | 9 (14) | Yes | $1.25 – $1.50 online |

| Spry Xylitol Gum (various flavors) | 0.72 | 8 (14) | Yes | $0.70 – $0.90 online |

| Tundra Trading “XyliChew Gum” | 0.80 | 8 (13) | Yes | $1.50 – $1.65 retail |

| Vitamin Research “Unique Sweet Gum” | 0.72 | 8 (14) | Yes | $0.75 – $1.00 online |

| WellDent Xylitol Gum | 0.70 | 9 (14) | Yes | $0.90 – $1.00 online |

| Altoids Sugar-Free Gum (Cinnamon/Peppermint) | 1st / 2nd of 4 polyols [1.0] | NC* | Maybe | $0.90 – $1.00 retail |

| B-Fresh Gums (various flavors) | 1st of 2 polyols [1.0] | NC | Maybe | $1.35 – $1.90 online |

| BreathRx “Halispheres Sugar-Free Gum” | 1st of 3 polyols | NC | Maybe | $0.85 – $1.60 online |

| Hershey “Ice Breakers Ice Cube” Gum | 1st of 5 polyols [2.0] | NC | Maybe | $0.80 – $1.00 retail |

| Starbucks “After Coffee Gum” Peppermint & Tangerine flavors only | 1st of 2 polyols [1.0] | NC | Maybe | $1.00 retail |

| Arm & Hammer “Dental Care Baking Soda Gum” | 2nd of 3 polyols [1.0] | NC | No | $0.80 – $1.00 retail |

| Arm & Hammer “Advance White Icy Mint Gum” | 2nd of 3 polyols [1.0] | NC | No | $1.00 – $1.30 retail |

| Biotene “Dry Mouth Gum” | 3rd of 3 polyols [1.0] | NC | No | $1.00 – $1.40 retail |

| Dentyne “Tango Gum” | 4th of 4 polyols [1.0] | NC | No | $0.70 – $1.10 online |

| Eco-Dent “Between Dental Gum” (various flavors) | 0.35 | 17 (29) | No | $1.05 – $1.70 online |

| Ferndale “glean whitening gum” | 0.05 3rd of 4 polyols [0.7] | 120 (200) | No | $0.75 – $110 online |

| Tully’s “vanilla mint gum” | 5th of 5 polyols | NC | No | $1.05 retail -Tully’s |

| Warner-Lambert “Trident Gum with Xylitol” (stick) | 2nd of 3 polyols [1.0] | NC | No | $0.55 – $0.70 retail |

| Warner-Lambert “Trident Gum with Xylitol” (pellet) | 3rd of 3 polyols [1.0] | NC | No | $0.85 – $1.00 retail |

| Warner-Lambert “Trident for Kids Gum” | 3rd of 3 polyols [1.0] | NC | No | $1.20 – $1.40 retail |

| Wrigley “Orbit Sugar-Free Gum” | 3rd of 3 polyols =0.04g [1.0] | NC | No | $0.72 – $0.80 retail |

| Ford Gum “Xtreme Sugar-free Gum” | NC | NC | NC | $0.65 – $0.85 online |

| MINTS: | ||||

| Biogenesis “Xylitol Peppermint Mints” | 0.55 | 11 (18) | Maybe | $1.00 – $1.25 online |

| Clen-Dent/Xponent “Mints” | 0.67 | 9 (15) | Yes | $0.62 – $0.70 online |

| Emerald Forest “Ricochet Xylitol Mints” | 0.4 | 15 (25) | Maybe | $0.30 – $0.35 online |

| Epic “Xylitol Mints” | 0.50 | 12 (20) | Maybe | $0.35 – $0.50 online |

| Nature’s Provision “Smart Smile Mints” (Xylipro) | 0.55 | 11 (18) | Maybe | $0.33 online |

| Omnii “Theramints” | 0.50 | 12 (20) | Maybe | $0.45 online |

| Spry “Mints” | 0.50 | 12 (20) | Maybe | $0.38 – $0.49 online |

| Tundra Trading “XyliChew Mints” | 0.55 | 11 (18) | Maybe | $0.35 – $0.50 retail |

| Vitamin Research “Unique Sweet Mints” | 0.50 | 12 (20) | Maybe | $0.50 – $0.65 online |

| WellDent “Xylitol Mints” | 0.55 | 11 (18) | Maybe | $0.38 online |

| Mint Asure breath capsules | 0.063 | 95 (160) | No | $0.75 retail |

| SMINT “Mints” (Regular & White) | < 0.20 | 30 (50) | No | $0.35 – $0.40 retail |

| Xlear “SparX” (candy – various flavors) | <0.25 | 25 (40) | No | $0.15 online |

| B-Fresh “Mints” | Only sweetener | NC | Maybe | $0.80 online |

| Brown & Haley “Zingos Caffeinated Peppermints” | 2nd of 2 polyols | NC | No | $0.40 – $0.50 retail |

| Hershey “Ice Breakers Center Ice” mints | 1st of 2 polyols | NC | No | $0.60 retail |

| Oxyfresh “Breath Mints” | 2nd of 2 polyols | NC | No | $0.35 – $0.40 online |

| Starbucks “After Coffee Mints” | 2nd of 2 polyols | NC | No | $0.20 Starbucks |

| Tic Tac “Silvers” (contains sugar) | NC | NC | No | $0.20 – $0.25 retail |

Cost varies based on retail, convenient stores, and internet vendors. Stated cost based on a few Seattle retailers or internet vendors.

Product list is not exhaustive. Xylitol market is rapidly changing and new xylitol containing products appear frequently.

“Yes”, “No”, or “Maybe” is based on the potential a person is willing to consume 2-3 pieces, 3 to 5 times per day to meet the effective dose range of 6 to 10 grams per day. Products with potential for effectiveness but xylitol dose is either unknown or required consumption is > 10 pieces per day to provide 6 g of xylitol are assigned “Maybe”.

NC = Not Certain. Information can not be derived from internet vendor, or market packaging, or not successful in obtaining information from vendors’ information representatives.

Table 2.

Xylitol-Containing Diet, Oral Hygiene, and Healthcare Products Available in U.S. Markets, and Their Xylitol Content

| PRODUCTS* | XYLITOL Content | COST†per unit | AVAILABILITY |

|---|---|---|---|

| ENERGY BARS & FOOD: | |||

| Barry Farm Sugar Free Jam (various flavors) | 3.6 g/ 20 g serving (18%) | $5.00/10 oz. | online |

| Barry Farm Sugar Free Pie Filling (various flavors) | 45 g/serving (36%) | $11.00/32 oz. | online |

| Buddha Bars/Vitality Bar | 4 – 5 g/bar | $3.00/bar | online |

| Dr. Ray’s Products “Gifu Xylitol Licorice” | 27%/piece | $0.75/30 pieces | online |

| Emerald Forest - Fudge Bar (sugar-free all flavors) | 20 g/2 oz serving | $10.00/15 oz. bar | online |

| Emerald Forest “Lena’s Jam” (various flavors) | 12 g/1 tbsp serving | $6.00/12 oz. | online |

| E Enterprises - “3 Bar” | 1 g/bar | $2.70/bar | online |

| Fran Gare’s “Decadent Desserts” Mix (various types) | 15 – 25 g/30 g serving | $7.00/canister | online |

| Jay Robb Enterprise “Jaybar” | 13–16 g/bar | $3.00/bar | online |

| Kraft Jell-O Pudding Sugar Free Chocolate | 7 g/serving | $0.65/serving unit | retail |

| Nature’s Hollow (Probst) – Sugar Free Jam Preserves | 4.5 g/20 g serving | $5.40/10 oz. | online |

| Nature’s Hollow – Sugar Free Syrup (various flavors) | 2.8 g/40 ml serving (7%) | $5.40/8.5 oz. | online |

| Nature’s Hollow – Sugar Free Ketchup | 0.8 g/20 g serving (4%) | $5.50/10 oz. | online |

| Nature’s Hollow – Sugar Free Honey | 1.6 g/20 g serving (8%) | $5.50/10 oz. | online |

| Smart Sweet Xylitol Jam (various flavors) | 8g/ 20 g serving | $7.00 /10 oz | online |

| ORAL HYGIENE: | |||

| Biotene “Dry Mouth Toothpaste/Gel” (+/− Calcium) | 10% | $6.00 – $8.00/4.5oz | retail & online |

| Crest “Multicare Cool Mint Toothpaste” | 10% | $3.30 – $4.50/6.2oz | retail & online |

| Epic “Fluoride-Free Xylitol Toothpaste” (no F) | 25% | $6.00/4.9oz | online |

| Epic “Xylitol & Fluoride Toothpaste” | 35% | $6.00/4.9oz | online |

| NOW “XyliWhite Toothpaste” Gel (no F) | 25% | $3.80 – $4.50/6.4 oz | retail & online |

| Spry Toothpaste (no F) | 25% | $2.70 – $5.00/4.0oz | online |

| Squigle “Enamel Saver Toothpaste” | 36% (0.24% sodium fluoride) | $7.00 – $11.00/4.0oz | online |

| Topex Toothpaste “Take Home Care”, “White Care” | 10% (1.1% sodium fluoride) | $4.50 – $5.50/2.0oz | dental office & online |

| Orajel “Dry Mouth Toothpaste” | NC†† 2nd of 2 polyols (last ingre.) | $5.00 – $7.00/4.5 oz. | retail & online |

| Oxyfresh “Super Relief Gel” & Fluoride Dental Gel” | NC only sweetener (2nd ingre.) | $13.50 – $15.00/4.0oz | online |

| Oxyfresh “Power Paste” toothpaste | NC 2nd of 2 polyols (7th ingre.) | $14.00/4.0 oz | online |

| Rembrandt Toothpaste “For Canker Sore” | NC only sweetener (5th ingre.) | $6.00 – $8.00/3oz | retail & online |

| Tom’s of Maine Toothpaste/Gel lines except Anticavity Cinnamint & “for children” Toothpaste contain NO xylitol | NC (varies in ingredient list) | $3.50 – $4.50/~6.0oz | retail & online |

| Tom’s of Maine Anticavity Liquid Gel “for children” | NC 2nd of 2 polyols (6th ingre.) | $4.00 – $5.00/4.60 oz | retail & online |

| Tundra Trading “XyliBrush Toothpaste” | N/C only sweetener (3rd ingre.) | $3.00 – $4.00/2.5 oz | online |

| Spry Infant “Tooth Gel” (no F) | 35% | $4.50 – $5.50/2.0oz | online |

| Laclede “First Teeth” Baby Toothpaste (no F) | NC 1st of 2 polyols (3rd ingre.) | $5.00 – $6.00/1.4oz | retail & online |

| Gerber Infant “Tooth & Gum Cleanser” (no F) | NC 1st of 2 polyols (3rd ingre.) | $5.00 – $6.00/1.4oz | retail & online |

| Gerber Toddler “Tooth & Gum Cleanser” (no F) | NC 2nd of 2 polyols (6th ingre.) | $5.00 – $6.00/1.4oz | retail & online |

| Oral-B “Stages Baby Tooth & Gum Cleanser” (no F) | NC 2nd of 2 polyols (6th ingre.) | $3.50/2.2 oz | retail & online |

| Dr. Ray’s Products “Spiffies Dental Wipes” | 0.65 g/wipe (only sweetener) | $5.50–$9.00/48 wipes | online |

| Epic “Oral Rinse” | 25% | $7.50 0 $8.50/16oz | online |

| Spry “Oral Rinse” (no F) | 22% | $3.70 – $5.50/16oz | online |

| Biotene “Oral Balance” Dry mouth gel or liquid | NC 2nd of 2 polyols | $5.00 – $8.00/1.5oz | retail & online |

| Biotene “Mouthwash” | NC 1st of 2 polyols | $6.00 – $7.70/16oz | retail & online |

| NOW “XyliWhite Mouthwash” | NC only sweetener (2nd ingre.) | $7.00/16oz | retail & online |

| Oasis “Mouth Spray” | NC only sweetener (last ingre.) | $5.00 – $7.00/1.0 oz. | retail & online |

| Orajel “Dry Mouth Moisturizing Spray” | NC 2nd sweetener (7th ingredient) | $5.00/1.65 oz | retail & online |

| Oxyfresh “Mouthrinses” (except Unflavored) | NC only polyol (2nd ingredient) | $9.00 – $13.50/16oz | online |

| Tom’s of Maine “Anticavity (fluoride) Mouthwash” | NC (varies in ingredient list) | $4.00 – $6.00/16.0oz | retail & online |

| Xylifloss “Pocket Dental Flosser” | NC | $4.00 / 250 uses | retain & online |

| HEALTHCARE: | |||

| Sultan “DuraShield” 5% Sodium Fluoride Varnish | NC (only sweetener) | $1.00/0.40mL dose | Rx – Dental office |

| Bayer “Flintstone Vitamins - Complete” | NC | $15–$17 / 150tabs | retail & online |

| Bayer “One a Day Kids Vitamins - Complete” | NC | $5.00–$8.50/50 tabs | retail & online |

| Jarrow Formulas “DentaShield” supplement | 1 g/chewable tablet | $16.00/60 tabs | retail & online |

| Sundown “Spiderman Complete Vitamins” | NC | $7.00–$8.00/60 tabs | retail & online |

| Micro Spray “Vitamin Sprays” | NC (2nd ingredient) | $13.00–$20.00/9ml | online |

| B&T “Echina Spray” | NC | $6.00–$10.00/0.68 oz | online |

| Nicorette “Gum”–Mint | NC (last ingredient) | $27–$33 / 40 pieces | retail & online |

| NOW “Activated Nasal Mist” with Xylitol | NC (2nd ingredient) | $9.00/2 oz | retail & online |

| Xlear “Nasal Wash” | NC (2nd ingredient) | $11.50–$14.00/1.5 oz | retail & online |

| Talking Rain “Kid’s Drink” with Xylitol | NC | $0.60/10 oz bottle | retail |

Product list is not exhaustive. Xylitol market is rapidly changing and new xylitol containing product appears frequently. Aside from toothpaste, most products have not been studied or published in peer-review journals thus the potential impact on caries reduction is not known.

Cost varies based on retail and convenient stores. Stated cost based on a few Seattle area retailers.

NC = Not Certain. Information can not be derived from market packaging and not successful in obtaining information from company information representative

Xylitol gum is being used in a publicly financed program for dental care access for pregnant women and their babies in rural Klamath Falls, Oregon. In this program, dentists are distributing xylitol gum free to new mothers who receive their dental care as part of the program. These private dentists are doing this because they are paid to provide dental care for the mothers and children at a fixed monthly rate and their profits are higher if dental disease is reduced. However, compliance with the use of the gum appears limited and we have much to learn about methods that would be most effective. Some private dental insurers have partnered with specialty companies whose focus is on producing dentally effective xylitol products to offer them at a reduced rate to their clients.

Xylitol chewing gum is not included on the formulary of Medicaid, the government insurance program that includes free dental care benefits for children and pregnant women from low-income families. The use of xylitol against dental caries was first recommended in a National Institutes of Health consensus conference in March 2001 (5). The American Dental Association does not have a formal position statement on the use of xylitol. The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry is developing one. Thus, it is unlikely that government insurance programs will be moved soon to provide low cost access to xylitol containing products.

Lack of Dosing and Frequency Guidelines

Another factor limiting the substantial use of xylitol until recently has been the lack of clear guidelines for making recommendations on how to use it effectively. Dental professionals have had to extrapolate from numerous studies using different products, even in a single study, different doses, and variable frequencies as to how xylitol use should be recommended to our patients. Dosing and frequency guidelines for xylitol have not been fully developed for its use as a therapeutic agent because there have been no prospective studies designed to determine the dose-response and frequency-response relationship of xylitol and S. mutans or dental caries thus establishing the minimum effective amount and frequency for using xylitol.

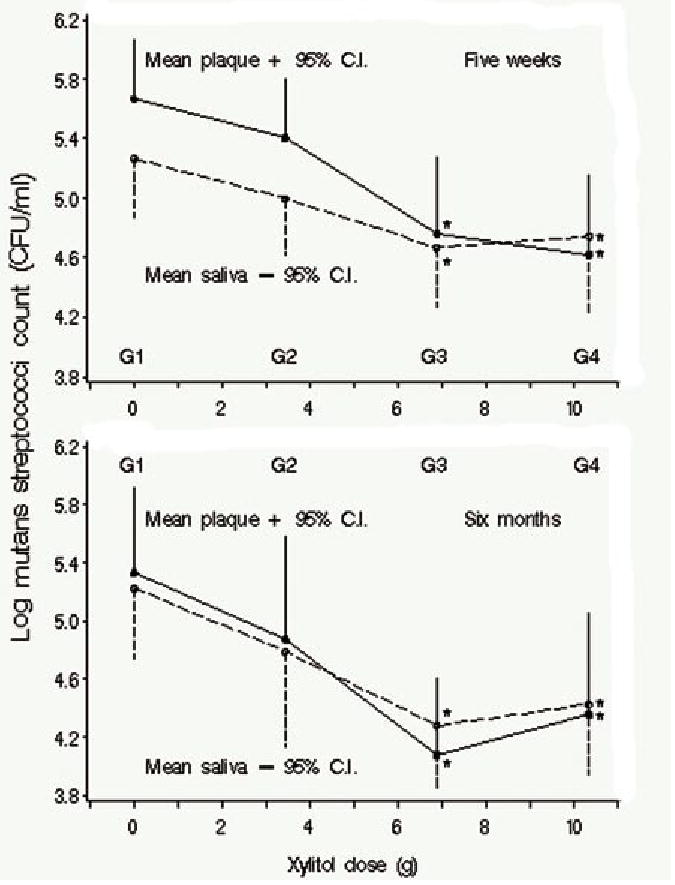

Our laboratory has now conducted a prospective series of studies with adults chewing xylitol gum to clarify the relationship of dose and frequency of use of xylitol to the reductions of mutans streptococci levels in plaque and saliva. In the initial dosage study (6), participants with high levels of mutans streptococci were randomly assigned to one of four groups given increasing amounts of xylitol per group. All groups chewed 12 pellets of gums per day divided into four pre-packaged administrations per day achieving the assigned xylitol dosage via a combination of control (sorbitol) and xylitol gum pellets. The participants were followed for six months taking plaque and saliva samples at baseline, five weeks, and six months. The study concluded that mutans streptococci levels were reduced in plaque and saliva with increasing doses of xylitol, with the effect leveling off between 6.88 g/day and 10.32 g/day (Figure 2). Although the smallest dose in the study, 3.44 g/day, showed a reduction, the difference was not statistically significant.

Figure 2.

Mean log10 CFU mutans streptococci/mL in plaque and unstimulated saliva by xylitol dose at 5 wks and at 6 mos. G1 is the condition in which subjects chewed the sorbitol placebo, G2 is the condition in which subjects chewed gums where the total daily dose was 3.44 g of xyliltol, G3 is the condition in which subjects chewed gums where the total daily dose was 6.88 g of xyliltol and G4 is the condition in which subjects chewed gums where the total daily dose was 10.32 g of xylitol. Subjects were randomly assigned to conditions and each person chewed the same number of pellets per day (12) divided into four periods. *Significant-difference group compared with placebo (G1) in least-significant-difference multiple comparisons. Reprinted with permission from J Dent Res 2006;85(2):177–81.

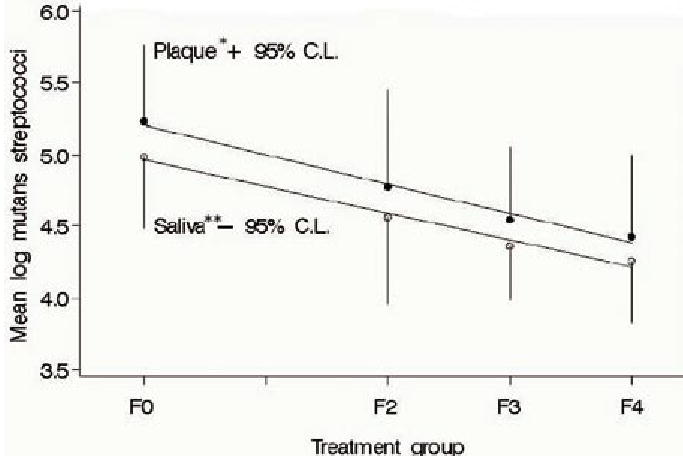

The second study in the series examined the relationship of the frequency of use of xylitol to the reduction of mutans streptococci at the maximum dosage used in the first study (7). Eligible adult participants with high levels of mutans streptococci were randomly assigned to one of four groups and followed over five weeks with plaque and saliva samples taken at baseline and five weeks. Three groups chewed gum containing 10.32 g/day of xylitol divided into two, three, or four administrations per day. The fourth group chewed an equal amount of the control gum (sorbitol) divided into four administrations per day. The results demonstrated a linear response where increasing frequency of use is associated with decreasing levels of mutans streptococci in plaque and saliva (Figure 3). However, although a reduction was observed with xylitol use of two times per day and the reduction was consistent with the linear line model, the difference was not statistically significant when compared to the sorbitol control group. These results are consistent with previous clinical findings. Thus, a range of 6 to10 grams divided into at least three consumption periods per day is necessary for xylitol chewing gum to be effective.

Figure 3.

Mutans streptococci counts in plaque and unstimulated saliva at five weeks and best fit linear line. F0 is the condition in which subjects chewed the sorbitol placebo four times per day. F2 is the condition in which the subjects chewed gum two times per day; F3 was the condition in which the subjects chewed gum three times per day; and F4 was the condition in which subjects chewed gum four times per day. In F2 to F4, the total dose per day of xylitol was 10.32 g. Subjects were randomized to conditions. Reprinted with permission.

Alternatives to Xylitol Chewing Gum

Chewing gum has been established as the most effective vehicle for the delivery of xylitol to the oral cavity. However, though this may be an effective means of consuming xylitol for most adult populations, it is a limiting factor for its use in small children and as a public health method of intervention in organized preschool programs.

The US has few organized caries prevention programs outside of public preschool programs called Head Start or in elementary schools with high concentrations of children from low-income families (often referred to children on free or reduced fee school lunch programs). In Head Start, programs are required to have children brush their teeth under supervision with fluoridated toothpaste and some programs in communities without fluoridated water dispense fluoride tablets. Head Start programs also are required to see that the children, typically about four years old, receive a dental examination and needed restorative care. However, compliance with these requirements varies as many dentists in these communities refuse to see such children and the poorest children live in communities with the most limited available dental care. Some elementary schools have fluoride rinse programs with little supervised tooth brushing or distribution of fluoridated toothpaste. These preventive efforts already have a track record for being difficult to carry out and the absence of an appropriate vehicle for xylitol delivery in organized programs remains a barrier to its adoption.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) does not recommend chewing gum use in children under four years old because of the risk of choking (8). Recent AAP policy, Oral Health Risk Assessment Timing and Establishment of the Dental Home, does recognize the value of xylitol gums for older children in its section on anticipatory guidance and patient education (9). On the other hand, teachers generally are opposed to the use of chewing gum at school (10). There are also concerns by teachers about being saddled with preventive health responsibilities that detract from teaching.

A large part of the caries problem is also centered in ethnic and minority preschoolers and their mothers. Thus any vehicles that would be used to deliver xylitol must be culturally appropriate as well as safe. Some minority cultures include proscriptions from gum chewing, at least during pregnancy. As can be seen in the Table, several xylitol-containing fluoridated toothpastes are being sold in the US. If such toothpastes were confirmed to be effective and child friendly, supervised brushing programs might be a partial answer to the dissemination problem.

A vehicle that delivers xylitol effectively in an organized caries prevention program for small children must be cost effective, appeal to children, and be easy to administer. In an effort to assess other possible vehicles our studies have sought to evaluate the acceptability (11,12) and compare the bioavailability of xylitol in snack foods and milk to xylitol chewing gum in both adults and children. The studies have demonstrated that children are willing to consume food snacks containing xylitol at school. Current work will demonstrate similar bioavailability and effectiveness of xylitol when chewing gum is compared to a chewable candy at comparable doses and frequencies.

An additional study is underway testing the effectiveness of xylitol syrup for the prevention of both dental caries and acute otitis media in infants in a US-associated island state. Such work hopefully will point to xylitol as a potential solution to the very high levels of both tooth decay and ear infections in isolated rural populations in the US and affiliated states. This work will also extend the previous limited findings of xylitol’s effect on acute otitis media (13).

Adoption of Xylitol by American Dentists is Slow

The benefits of xylitol in caries control and reduction have been well established over the last several decades through numerous research studies. Nevertheless, it is clear that the professional dental community in the United States has yet to adopt the use of xylitol on a routine basis either in private practice or in community health programs. It is interesting to note that the rate and method by which new modalities are adopted by groups in society such as the dental profession has been studied and identified as the diffusion theory. According to this theory innovations are not adopted on their own merits, but through predictable patterns of communication. Fiset and Grembowski used the diffusion theory to evaluate the adoption of the medical model in dentistry for the treatment of caries: use of sealants, fluoride varnishes, chlorhexidine rinses, and salivary function tests (14). Additionally, they assessed what factors made practitioners early adopters versus late adopters of this model of care. Typically the early adopter of a new service had dentist friends who were using it, whereas reading journals and continuing education did not affect the rate of adoption of these services.

Diffusion research may indicate that the limited exposure of the professional dental community in the United States to the potential dental benefits of xylitol will not be remedied by more being written about xylitol in the scientific literature. It appears rather that the pattern of adoption is similar to the effect of the ripples in a pond. The early adopters as always will try new techniques, innovations, and models and the late adopters will get on board as it becomes necessary to keep up with the trend. The medical detailing approach favored by pharmaceutical companies may be helpful as might introduction of xylitol at dental study clubs and courses. There is also likely to be a certain amount of market pressure from internet literate dental consumers regarding the availability and use of xylitol products. The number and variety of products containing xylitol has recently begun to increase and direct consumer advertising is likely to follow.

As the guidelines for the effective use of xylitol are being clarified, the demand by consumers and dental professionals for well labeled, less expensive products may also affect the producers. The xylitol habit must be maintained to remain effective. While this plays into the hand of those who manufacture the products, it behooves the dental profession to seek delivery vehicles that decrease the burden of use for those who need it most (15). Real solutions to the adoption of xylitol rest in the hands of insurance companies, government program administrators and their advisors, and in organized programs for those who suffer health disparities (16). Diffusion of the use of xylitol as a caries prevention measure remains a challenge, but the greater challenge is to find a method and the appropriate vehicle to incorporate this potent tool into the community dental health programs of those high-risk populations who need it the most.

Acknowledgments

Work cited in this paper was supported in part by Grants No. 1 P50 DE14254 and T32 DE07132 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD and Grant No. R40MC03622 from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources Services Administration, Rockville, MD.

References

- 1.Wikipedia contributors. Xylitol. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. May 30, 2006, 20:53 UTC. [Accessed May 30, 2006]. Available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Special:Cite&oldid= [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson MH, Bales DJ, Omnell KA. Modern management of dental caries: the cutting edge is not the dental bur. J Am Dent Assoc. 1993;124(6):36–44. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1993.0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calorie Control Council. Xylitol. Atlanta, GA: Mar, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ly KA, Milgrom P, Rothen M. Xylitol, sweeteners, and dental caries. Pediatr Dent. 2006;28(2):154–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayes C. The effect of non-cariogenic sweeteners on the prevention of dental caries: a review of the evidence. J Dent Educ. 2001;65(10):1106–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milgrom P, Ly KA, Roberts MC, Rothen M, Mueller G, Yamaguchi DK. Mutans streptococci dose response to xylitol chewing gum. J Dent Res. 2006;85(2):177–81. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ly KA, Milgrom P, Roberts MC, Yamaguchi DK, Rothen M, Mueller G. Linear response of mutans streptococci to increasing frequency of xylitol chewing gum use: a randomized controlled trial [ISRCTN43479664] BMC Oral Health. 2006;6(1):6. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-6-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Academy of Pediatrics. Choking prevention. [Accessed May 30, 2006.]. Available at: http://www.aap.org/pubed/ZZZSEN9YA7C.htm?&sub_cat=1. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Policy statement. Oral health risk assessment timing and establishment of the dental home. Pediatrics. 2003;111(5):1113–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.5.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Autio JT, Courts FJ. Acceptance of the xylitol chewing gum regiment by preschool children and teachers in a Head Start program: a pilot study. Pediatr Dent. 2001;23(1):71–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lam M, Riedy CA, Coldwell SE, Milgrom P, Craig R. Children’s acceptance of xylitol-based foods. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28(2):97–101. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2000.028002097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castillo JL, Milgrom P, Coldwell SE, Castillo R, Lazo R. Children’s acceptance of milk with xylitol or sorbitol for dental caries prevention. BMC Oral Health. 2005;5(1):6. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-5-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uhari M, Kontiokari T, Niemela M. A novel use of xylitol sugar in preventing acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 1998;102(4Pt1):879–84. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.4.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiset L, Grembowski D. Adoption of innovative caries-control services in dental practice: a survey of Washington dentists. J Am Dent Assoc. 1997;128(3):337–45. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1997.0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glassman P, Anderson M, Jacobsen P, et al. Practical protocols for the prevention of dental disease in community settings for people with special needs: the protocols. Spec Care Dentist. 2003;23(5):160–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2003.tb00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patrick DL, Lee RSY, Nucci M, Grembowski D, Jolles CZ, Milgrom P. Reducing oral health disparities: A focus on social and cultural determinants. BMC Oral Health. 2006 doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-6-S1-S4. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]