Abstract

In mammalian cells, as well as Escherichia coli, ribosomes translating membrane proteins interact cotranslationally with translocons in the membrane, and this interaction is essential for proper insertion of nascent polypeptides into the membrane. Both the signal recognition particle (SRP) and its receptor (SR) are required for functional association of ribosomes translating integral membrane proteins with the translocon. Herein, we confirm that membrane targeting of E. coli ribosomes requires the prokaryotic SRα homolog FtsY in vivo. Surprisingly, however, depletion of the E. coli SRP54 homolog (Ffh) has no significant effect on binding of ribosomes to the membrane, although Ffh depletion is detrimental to growth. These and other observations suggest that, in E. coli, SRP may operate downstream of SR-mediated targeting of ribosomes to the plasma membrane.

In mammalian cells, integral membrane proteins, as well as many secreted proteins, are targeted to the endoplasmic reticulum cotranslationally via the signal recognition particle (SRP) and its receptor (SR). In the current view of the SRP pathway, when a newly synthesized signal peptide exits the ribosome, the mRNA-nascent chain-ribosome complex interacts with SRP, and the entire complex is then targeted to the membrane where it associates with a heterodimeric SR (1). Once the primary sequences of the major mammalian SRP components were identified (2, 3) and shown to be homologous to Escherichia coli genes of previously unknown function, it became apparent that bacteria possess an SRP-like system with three components: (i) a 4.5S RNA that has homology with the longer mammalian 7S RNA (reviewed in ref. 4); (ii) Ffh, a homolog of the mammalian SRP54 protein; and (iii) FtsY, in which the 300-residue C-terminal NG domain resembles the C-terminal NG domain of the mammalian SR α-subunit (SRα). Notably, all E. coli SRP components are essential for cell growth (5–8), and recent studies suggest that they mediate targeting of at least certain proteins to the cytoplasmic membrane (9–13). The notion that E. coli has an SRP-like complex receives further support from the demonstration that SRP components interact with each other (reviewed in ref. 14) and that there is an interaction between SRP and the nascent chain-ribosome complex (15). Once SRP-mediated targeting of ribosomes translating membrane proteins occurs, presumably the nascent polypeptides are inserted into the membrane via translocation (Sec) machinery embedded in the membrane. Evidence supporting this concept (16–20) shows that, at a late step during targeting, the SRP system transfers the ribosome-nascent chain complex to the Sec complex. The realization that a homologous system is present in bacteria has led to the use of powerful biochemical and genetic approaches to study the structure and function of each SRP component, as well as the cascade of events underlying membrane protein insertion. In this communication, one of the central issues in membrane protein insertion, targeting of ribosomes to the cytoplasmic membrane, is addressed in vivo.

Experimental Procedures

Materials.

Kanamycin, chloramphenicol, puromycin, ampicillin, PMSF, arabinose, and isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside were purchased from Sigma, and prestained protein molecular mass markers were from BioLabs (Northbrook, IL). Anhydrotetracycline-HCl was from Acros Organics (Fairlawn, NJ), and GTP was obtained from Roche Molecular Biochemicals. Antibodies were obtained from the following sources: anti-FtsY from M. Muller (Freiburg University, Freiburg, Germany), anti-Ffh from J. Luirink (Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam), anti-ribosomal proteins from F. Franceschi (MPI, Berlin), anti-SecY from A. J. M. Driessen (Groningen University, Groningen, The Netherlands), and goat-anti-rabbit and donkey-anti-goat antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase from Jackson Immuno-Research.

Bacterial Strains.

E. coli WAM113 (ffh1∷kan;attB∷R6Kori ParaBADffh) was used for depletion of Ffh (6); E. coli N4156∷pAra14-FtsY′ was used for depletion of FtsY (8); and E. coli HA101 (see below) was used for the simultaneous depletion of both FtsY and Ffh. E. coli N4156 was used to characterize the fractionation procedures used (Fig. 1).

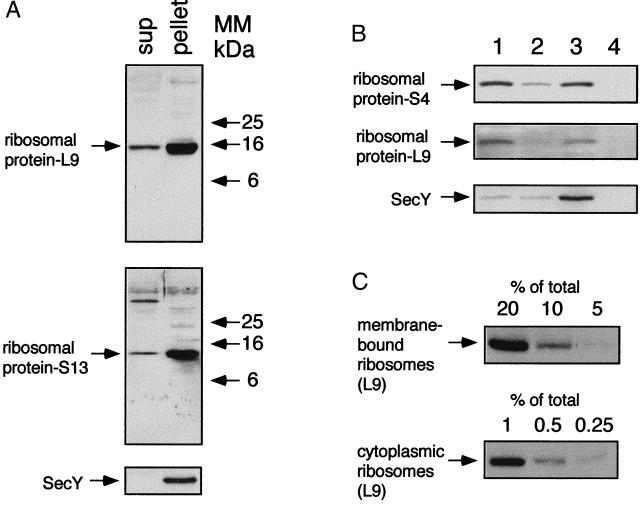

Figure 1.

Isolation of membrane-bound ribosomes. A culture of E. coli N4156 was grown in LB broth to 0.8 units of OD600. (A) Cell extracts were subjected to ultracentrifugation, and the isolated fractions (sup, 20 μg of proteins; pellet, 10 μg of proteins) were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against ribosomal proteins and SecY. MM, molecular mass. (B) The cellular distribution of ribosomes was studied by flotation by using the pellet that was prepared as described in A. The fractions (lane 1, bottom; lane 2, middle; lane 3, interface; lane 4, top) were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against ribosomal proteins and also with antibodies against the membrane protein SecY. (C) Decreasing amounts (as indicated) of proteins from fractions 3 (interface) and 1 (bottom) were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against the ribosomal protein L9.

Construction of E. coli HA101.

The FtsY conditional stain N4156∷pAra14-FtsY′, which contains the ftsY gene under the control of the araB promoter, was used as the parent strain for construction of E. coli HA101. Conditional expression of ffh is accomplished by producing a knockout mutation in the chromosomal ffh gene (ffh∷kan) in combination with a complementing copy of ffh under regulation of the tight tet promoter (PLtetO-1; ref. 21) carried by a low copy number plasmid (pSC101). First, the ffh gene without its native promoter was obtained from the chromosome by PCR with two primers, one with a KpnI restriction site and the other with a MluI restriction site. The PCR fragment digested with KpnI and MluI was cloned under the PLtetO-1 promoter in plasmid pZS*2tet-1MCS1 (Cm; ref. 21) by using the same restriction enzymes, thereby creating plasmid pZS*-2tet-ffh. This plasmid also encodes the tet repressor (R. Rajsbaum and E.B., unpublished data). Second, the wild-type ffh gene of E. coli N4156∷pAra14-FtsY′ was replaced by a deleted version (ffh∷kan) by using P1 transduction with E. coli WAM113 as a donor strain. Transductants were grown on LB plates containing kanamycin (30 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml), and the inducers arabinose (0.2%) and anhydro-tetracycline (100 ng/ml) for expression of FtsY and Ffh, respectively.

Growth Conditions.

Cultures were grown at 37°C in LB medium supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml) or kanamycin (30 μg/ml) when necessary. For FtsY and/or Ffh depletion, cells were grown overnight with arabinose (0.2%) or with arabinose and anhydrotetracycline (100 ng/ml), washed three times in LB broth, and resuspended in LB to an OD600 of 0.01 with or without arabinose and/or anhydrotetracycline, as indicated. Growth was estimated from cell density as monitored by the increase in OD600.

Cell Fractionation.

Harvested cells were resuspended in ice-cold 10 mM Tris-acetate (pH 7.6)/10 mM Mg(OAc)2/60 mM NH4Cl/0.25 M sucrose (RS buffer; ref. 22) supplemented with 1 mM PMSF to an OD420 of 2.1. Extracts were prepared by three freeze/thaw cycles, followed by three cycles of brief sonication (4 s at 1-min intervals). Extracts were incubated on ice for 20 min with 10 μg/ml DNase I and 1 mM PMSF and subjected to low-speed centrifugation to remove cell debris. Membranes and ribosomes were collected by ultracentrifugation with an Optima benchtop centrifuge (Beckman–Spinco) with a TLA 100.1 rotor (60 min; 90,000 rpm; 4°C). Pellets were resuspended in buffer R [10 mM Tris-acetate, pH 7.6/10 mM Mg(OAc)2/60 mM NH4Cl] supplemented with 1 mM PMSF. Identical aliquots of protein from each sample (usually 40 μl containing 300 μg of protein) were placed in empty tubes, mixed with 400 μl of buffer R containing 2.3 M sucrose and overlaid with 680 μl of buffer R containing 1.9 M sucrose. Tubes were filled to the top with buffer R as described (23). Flotation was accomplished by ultracentrifugation with an Optima benchtop centrifuge (Beckman–Spinco) with a TLS 55 rotor (4 hr; 54,000 rpm; 4°C). Fractions were diluted to 0.5 M sucrose in buffer R, precipitated on ice overnight in trichloroacetic acid (10% wt/vol), and washed with ice-cold acetone.

Puromycin and High Salt Treatment.

Harvested cells were suspended in ribosome release buffer [50 mM Hepes, pH 7.8/10 mM Mg(OAc)2/60 mM KOAc/0.25 M sucrose/1 mM EDTA] and gently disrupted as described earlier. Puromycin (2 mM), GTP (0.1 mM), and DTT (3 mM) were then added to the cell extracts that were incubated on ice for 1 hr, followed by incubation at 37°C for 15 min and then at room temperature for 15 min. Each sample was then divided into four identical aliquots and centrifuged with an Optima benchtop centrifuge (Beckman–Spinco) with a TLA 100.1 rotor (60 min; 90,000 rpm; 4°C). Pellets were resuspended and incubated for 1 hr on ice in ribosome release buffer containing different concentrations of KOAc (60, 400, 600, and 800 mM) and subjected to flotation in a stepwise sucrose gradient as described earlier. Ultracentrifugation was done at 20°C.

Gel Electrophoresis and Immunoblotting.

Protein concentrations were measured according to a modified Lowry procedure in the presence of 2.5% (wt/vol) SDS with BSA as a standard. An aliquot from each sample was then mixed with SDS sample buffer, incubated at 37°C for 15 min or 100°C for 5 min (with samples of ribosomal proteins), and analyzed by SDS/7.5–12% PAGE by using acrylamide (NaDodSO4). After electroblotting, the nitrocellulose was incubated with the appropriate primary antibody and then with goat anti-rabbit or donkey anti-goat antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. The nitrocellulose was soaked briefly in fluorescent substrate solution and exposed to film for 10–30 s, as required.

Results and Discussion

Cell Fractionation.

A prerequisite to studying cellular distribution of ribosomes in E. coli is to establish a protocol for clearly discriminating between cytosolic and membrane-associated ribosomes. It has been shown (e.g., ref. 23) with mammalian microsomes that membrane-bound ribosomes can be separated from cytosolic ribosomes by flotation in a stepwise sucrose gradient. Therefore, E. coli N4156 cells were disrupted as described (22, 24) and subjected to ultracentrifugation to isolate both the cytosolic and the membrane-bound ribosomes (Fig. 1A). As shown with antibodies against proteins from the ribosomal large (L9) and small (S13) subunits, most of the ribosomes are detected in the pellet with the polytopic membrane proteins SecY (Fig. 1A) and LacY (data not shown). The ribosome-containing pellet was then subjected to flotation, and the sucrose gradient fractions were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against ribosomal subunit proteins L9, S4, and either SecY (Fig. 1B) or LacY (data not shown). Clearly, L9 and S4 detected in fraction 3 comigrate with SecY (Fig. 1B), as well as LacY (not shown). Semiquantitative Western blot analysis with anti-L9 antibodies (Fig. 1C) indicates that approximately 6–7% of the ribosomes are membrane bound, as shown previously (22). Moreover, the membrane-bound ribosomes are probably associated with mRNA and active in translation (ref. 22 and 24; see below).

FtsY Depletion.

Ribosome distribution in cells depleted of FtsY, the E. coli SRα homolog, was studied by similar fractionation experiments with samples taken from cultures of the well characterized E. coli N4156∷pAra14- FtsY′ (8), which contains a chromosomal copy of the ftsYEX operon under the tight control of the araB promoter. The essential genes ftsE and ftsX are transcribed also independently of ftsY (25). Growth of the strain ceases without arabinose (Fig. 2A), because FtsY is an essential protein; by 3 hr, FtsY is virtually undetectable (Fig. 2B), whereas Ffh, the E. coli homolog of SRP54, is unaffected. As shown previously (12), expression of membrane proteins such as SecY (Fig. 2B) is inhibited in FtsY-depleted cells. When arabinose was added to the depleted cultures, full restoration of FtsY expression is observed (Fig. 2B). Similarly, expression of SecY is also restored after FtsY induction (Fig. 2B).

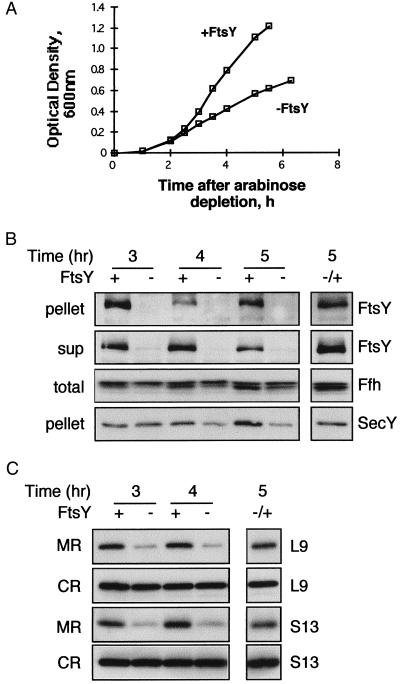

Figure 2.

Effect of FtsY depletion on the cellular distribution of ribosomes. (A) Growth of E. coli N4156∷pAra14-FtsY′ with or without arabinose was monitored by measuring the optical density of the cultures every 30 min. Samples were taken at certain time points during the growth, fractionated as described in Fig. 1, and analyzed by Western blotting as shown in B (ultracentrifugation of cell extracts) and C (flotation assay). (B and C) In both panels, the separated lane on the right represents samples from depleted cultures that were induced with arabinose after 4 hr of depletion and harvested 1 hr later. (B) Extracts were prepared from N4156∷pAra14-FtsY′ cells that were grown with or without arabinose (A). Pellets (10 μg of proteins) were probed with anti-FtsY and anti-SecY antibodies; supernatants (sup; 20 μg of proteins) were probed with anti-FtsY antibodies; and total extracts (total; 10 μg of proteins) were probed with anti-Ffh antibodies. (C) After flotation, identical aliquots from the interface fractions (membrane ribosomes, MR) and the bottom fractions (cytoplasmic ribosomes, CR) were probed with antibodies against the ribosomal proteins L9 and S13.

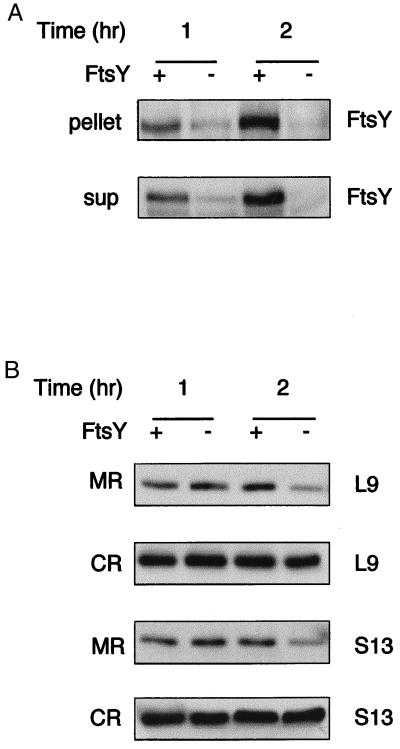

The effect of FtsY depletion on membrane-bound ribosomes was analyzed after further fractionation of the pellets obtained from ultracentrifugation (Fig. 2B) by flotation. Both the isolated membranes and the free ribosomal fractions were then analyzed by Western blotting with polyclonal antibodies against L9 and S13. On depletion of FtsY, membrane-associated ribosomes are reduced by approximately 75%, whereas cytoplasmic ribosomes remain essentially constant (Fig. 2C). Induction of FtsY expression in cells depleted of FtsY leads to the reappearance of ribosomes in the membrane fraction (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, unlike SecY, which decreases partially after FtsY depletion (Fig. 2B), expression of FtsY, L9, and S13 in the membrane fraction decreases much more drastically after a 3-hr depletion. Therefore, expression of FtsY and ribosomal proteins was studied over a shorter time period after arabinose depletion (Fig. 3). Strikingly, expression of FtsY decreases markedly after only 1 hr after arabinose depletion (Fig. 3A), indicating a relatively short half-life. Over 1–2 hr, the membrane-bound ribosomes also decrease, but they seem to do so at a slower rate (Fig. 3B). Therefore, although ribosome targeting to the membrane is FtsY dependent (Figs. 2 and 3), ribosomes may remain anchored to the membrane for a short time after FtsY has been depleted. It is also possible that after a 1-hr depletion, the small amount of FtsY that is translated is sufficient for targeting ribosomes to the membrane. In any case, the observations support the proposal that membrane targeting of ribosomes in E. coli requires FtsY.

Figure 3.

Effect of FtsY depletion on the cellular distribution of ribosomes shortly after depletion. E. coli N4156∷pAra14-FtsY′ was grown with or without arabinose, and samples were taken 1 and 2 hr after arabinose depletion. The cells were fractionated as described for Fig. 1 and analyzed by Western blotting as shown in A (ultracentrifugation of cell extracts) and B (flotation assay). (A) Extracts were prepared from N4156∷pAra14-FtsY′ cells that were grown with or without arabinose. Pellets (10 μg of proteins) were probed with anti-FtsY; supernatants (sup; 20 μg of proteins) were probed with anti-FtsY antibodies. (B) After flotation, identical aliquots from the interface fractions (membrane ribosomes, MR) and the bottom fractions (cytoplasmic ribosomes, CR) were probed with antibodies against the ribosomal proteins L9 and S13.

Ffh Depletion.

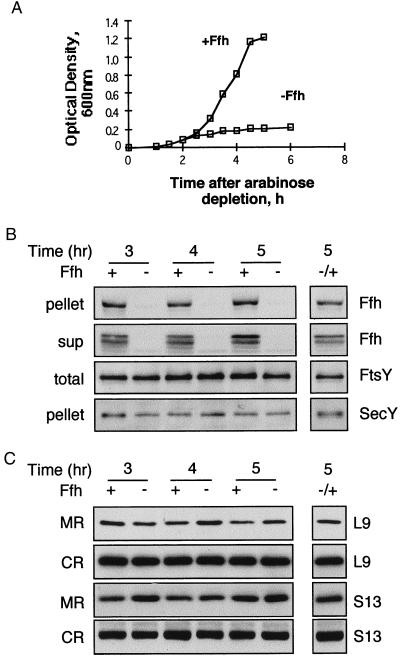

In a similar manner, the role of SRP (Ffh) in targeting ribosomes to the membrane was studied directly by analyzing ribosome distribution in Ffh-depleted E. coli Wam113 (6), which contains a chromosomal copy of the ffh gene under the tight control of the araB promoter (Fig. 4). Growth of Wam113 also ceases when arabinose is removed from the medium, because Ffh, like FtsY, is an essential protein (Fig. 4A). At 3 hr after arabinose depletion, Ffh is drastically reduced (Fig. 4B), whereas FtsY expression is unaffected. Unlike FtsY-depleted cells, where expression of SecY is inhibited (Fig. 2B), in Ffh-depleted cells, SecY expression remains unchanged (Fig. 4B). Thus, the effect of Ffh depletion differs from FtsY depletion, probably because Ffh depletion prevents proper membrane protein assembly (9–11) but has little or no effect on expression per se. When arabinose is added back to the culture, full restoration of Ffh is observed (Fig. 4B). Surprisingly, after fractionation of the pellets obtained from ultracentrifugation (Fig. 4B) by flotation, it is apparent that Ffh depletion has no detectable effect on recovery of membrane-bound ribosomes despite its putative role in ribosome targeting as part of the SRP complex (Fig. 4C). As observed with E. coli expressing Ffh, similar amounts of L9 and S13 are detected in membranes isolated from Ffh-depleted cells even 5 hr after depletion. A plausible explanation for the observations is that SRP is not required for membrane association of E. coli ribosomes. However, because Ffh depletion does not affect expression of membrane proteins (Fig. 4B), it is important to examine the possibility that ribosomes in Ffh-depleted cells may bind to the membrane in a nonspecific manner via hydrophobic nascent chains.

Figure 4.

Effect of Ffh depletion on the cellular distribution of ribosomes. (A) Growth of E. coli WAM113 with or without arabinose was monitored by measuring the optical density of the cultures every 30 min. Samples were taken at certain time points during the growth, fractionated as described for Fig. 1, and analyzed by Western blotting as shown in B (ultracentrifugation of cell extracts) and C (flotation assay). (B and C) In both panels, the separated lane on the right represents samples from depleted cultures that were induced with arabinose after 4 hr of depletion and harvested 1 hr later. (C) Extracts were prepared from WAM113 cells that were grown with or without arabinose (A). Pellets (10 μg of proteins) were probed with anti-Ffh and anti-SecY antibodies; supernatants (sup; 20 μg of proteins) were probed with anti-Ffh antibodies; and total extracts (total; 10 μg of proteins) were probed with anti-FtsY antibodies. (C) After flotation, identical aliquots from the interface fractions (membrane ribosomes, MR) and the bottom fractions (cytoplasmic ribosomes, CR) were probed with antibodies against the ribosomal proteins L9 and S13.

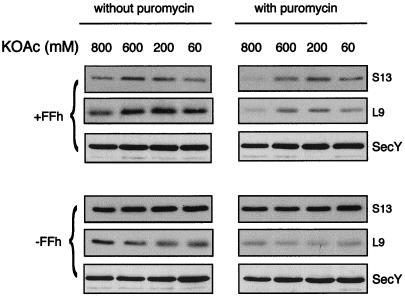

The nature of the interaction between ribosomes and membranes from Ffh-depleted and nondepleted cells was analyzed by treating membranes with puromycin, followed by incubation at increasing concentrations of salt (Fig. 5). Puromycin acts by interrupting chain elongation, and ribosomes detach from the puromycin-terminated nascent chains at high salt conditions (e.g., ref. 26). Therefore, if ribosomes in Ffh-depleted cells are attached to the membrane nonspecifically, they should be removed from the membrane after treatment with puromycin and high salt (26). Although a large fraction of the ribosomes (75%) is released from the membranes of nondepleted cells, indicating that these ribosomes are involved in active translation, puromycin/high salt does not alter the amount of ribosomes that fractionate with membranes from Ffh-depleted cells (Fig. 5). Therefore, in Ffh-depleted cells, the ribosomes bind to the membrane through relatively strong interactions. Consistent with the conclusion that ribosomes do not bind nonspecifically to the membrane, previous studies (27) on the interaction between eukaryotic ribosomes and target membranes demonstrate that under physiological conditions, most nonspecific membrane binding of ribosomes is lost. Thus, we favor the hypothesis that the lethal effect of Ffh depletion is not due to defective ribosome targeting to the membrane but is caused possibly by a role of Ffh in assembly of membrane proteins (9–11).

Figure 5.

Effect of puromycin/high salt treatment on the amount of membrane-bound ribosomes in Ffh depleted and nondepleted cells. Extracts prepared from E. coli WAM113 grown with or without arabinose were incubated with or without puromycin (as indicated), and the ultracentrifuged pellets were resuspended and incubated in ribosome release buffer containing various KOAc concentrations. After flotation, identical aliquots from the interface fractions (containing membrane-bound ribosomes) were subjected to Western blotting with antibodies against the ribosomal proteins L9 and S13, as well as with anti-SecY antibodies.

Simultaneous Depletion of FtsY and Ffh.

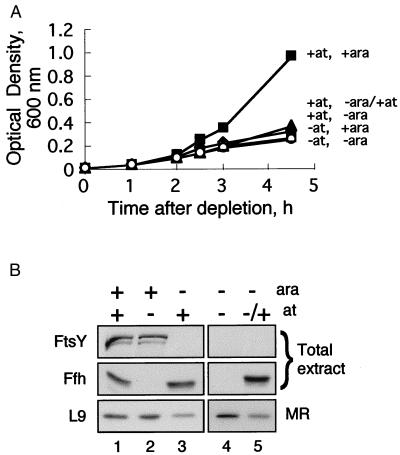

To exclude a possible caveat that may result from the use of strains with different genotypes, the experiments described above have been reproduced by using the recently constructed E. coli HA101. This strain harbors both ftsY and ffh under the tightly regulated promoters araB and tet, respectively (see Experimental Procedures). E. coli HA101 were depleted of Ffh, FtsY, or both. Growth was inhibited in all of the cultures depleted of either or both inducers (Fig. 6A). Samples were taken after 3 hr, and FtsY, Ffh, and membrane-bound ribosomes were analyzed. As shown in Fig. 6B, membrane-bound ribosomes decrease in cells depleted of FtsY (lane 3), and no change is apparent in cells depleted of Ffh (lane 2). Membrane-bound ribosomes also remain unaffected in cells simultaneously depleted of Ffh and FtsY (lane 4). It is possible that FtsY has initiated membrane association of ribosomes, but after depletion of both Ffh and FtsY, release of these ribosomes from the membrane is no longer possible. However, ribosomes are released from the membrane after induction of Ffh (lane 5). In addition to providing further support for the conclusion that FtsY, but not Ffh, is required for association of ribosomes with the inner membrane, the results suggest that Ffh may play a role in the release of ribosomes from a initial, puromycin/high salt-insensitive membrane binding site and their subsequent transfer to the translocon.

Figure 6.

Effect of FtsY or Ffh depletion in an isogenic background on the cellular distribution of ribosomes. (A) E. coli HA101 cultures were grown with or without arabinose (for induction of FtsY) or anhydrotetracycline (for induction of Ffh), and the growth was monitored by measuring the optical density of the cultures when indicated. (B) After 3 hr, samples were withdrawn, and cells were fractionated as described for Fig. 1. Lane 5 represents samples that were taken from cells grown without arabinose and anhydrotetracycline for 3 hr and then induced with anhydrotetracycline for 1.5 hr. Total extracts (20 μg of proteins) were separated by SDS/PAGE and subjected to Western blotting with anti-FtsY and anti-Ffh antibodies. After flotation, identical aliquots from the interface fractions (membrane ribosomes, MR) were probed with antibodies against the ribosomal protein L9.

Given the assumption that like the mammalian FtsY-homolog SRα (28), FtsY may also be targeted and assembled cotranslationally on the membrane (as may be inferred indirectly from ref. 29), the observations presented herein raise an important consideration regarding a possible role for FtsY in ribosome targeting, namely that both FtsY and the ribosomes translating it are delivered together to the membrane. One consequence of such a scenario is that the SRP complex may not participate in ribosome targeting unless targeting of FtsY itself is SRP dependent. In this regard, it has been shown that the cotranslational targeting of the mammalian SR does not require SRP (28).

In conclusion, although the prevailing SRP model in E. coli implies that the SRP complex plays a critical role in targeting of ribosomes to the membrane, this conclusion is not supported by the experiments presented herein. However, it is noteworthy that the SRP model has been derived primarily from in vitro studies, whereas these results were obtained from experiments carried out in vivo. Clearly, further studies are needed both to test the hypothesis that FtsY may mediate ribosome targeting in the absence of SRP and to correlate evidence obtained in vitro with the in vivo studies now feasible both in E. coli and in yeast.

Acknowledgments

We thank F. Franceschi, M. Muller, J. Luirink, and A. J. M. Driessen for their gifts. We thank S. Avkin for her assistance during the construction of E. coli HA101. We are grateful to R. Edgar and E. Bochkareva for their encouragement and help. This work was supported by the German-Israeli Foundation for Scientific Research and Development and by the Israel Science Foundation.

Abbreviations

- SRP

signal recognition particle

- SR

SRP receptor

Footnotes

Article published online before print: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 10.1073/pnas.080077197.

Article and publication date are at www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.080077197

References

- 1.Walter P, Johnson A E. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1994;10:87–119. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.10.110194.000511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernstein H D, Poritz M A, Strub K, Hoben P J, Brenner S, Walter P. Nature (London) 1989;340:482–486. doi: 10.1038/340482a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romisch K, Webb J, Herz J, Prehn S, Frank R, Vingron M, Dobberstein B. Nature (London) 1989;340:478–482. doi: 10.1038/340478a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bovia F, Strub K. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:2601–2608. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.11.2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown S, Fournier M J. J Mol Biol. 1984;178:533–550. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90237-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phillips G J, Silhavy T J. Nature (London) 1992;359:744–746. doi: 10.1038/359744a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gill D R, Salmond G P C. Mol Gen Genet. 1987;210:504–508. doi: 10.1007/BF00327204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luirink J, ten Hagen-Jongman C M, van der Weijden C C, Oudega B, High S, Dobberstein B, Kusters R. EMBO J. 1994;13:2289–2296. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Macfarlane J, Muller M. Eur J Biochem. 1995;233:766–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.766_3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Gier J-W L, Mansournia P, Valent Q A, Phillips G J, Lurink J, von Heijne G. FEBS Lett. 1996;399:307–309. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01354-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ulbradt N D, Newitt J A, Bernstein H D. Cell. 1997;88:187–196. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81839-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seluanov A, Bibi E. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:2053–2055. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Gier J W, Scotti P A, Saaf A, Valent Q A, Kuhn A, Luirink J, von Heijne G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14646–14651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Gier J W, Valent Q A, Von Heijne G, Luirink J. FEBS Lett. 1997;399:307–309. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01354-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luirink J, High S, Wood H, Giner A, Tollervey D, Dobberstein B. Nature (London) 1992;359:741–743. doi: 10.1038/359741a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prinz W A, Boyd D H, Ehrmann M, Beckwith J. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:8419–8424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.8419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newitt J A, Bernstein H D. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12451–12456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qi H Y, Bernstein H D. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8993–8997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valent Q A, Scotti P A, High S, de Gier J-W L, von Heijne G, Lentzen G, Wintermeyer W, Oudega B, Luirink J. EMBO J. 1998;17:2504–2512. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.9.2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck K, Wu L-F, Brunner J, Müller M. EMBO J. 2000;19:134–143. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.1.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lutz R, Bujard H. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1203–1210. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.6.1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Randall L L, Hardy S J S. Eur J Biochem. 1977;75:43–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lauring B, Kreibich G, Weidmann M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9435–9439. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Randall L L, Hardy S J S. Methods Enzymol. 1983;97:70–77. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)97120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gill D R, Salmond G P C. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:575–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gorlich D, Prehn S, Hartmann E, Kalies K U, Rapoport T A. Cell. 1992;71:489–503. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90517-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalies K-U, Gorlich D, Rapoport T A. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:925–934. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.4.925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Young J C, Andrews D W. EMBO J. 1996;15:172–181. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zelazny A, Seluanov A, Cooper A, Bibi E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6025–6029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]