Abstract

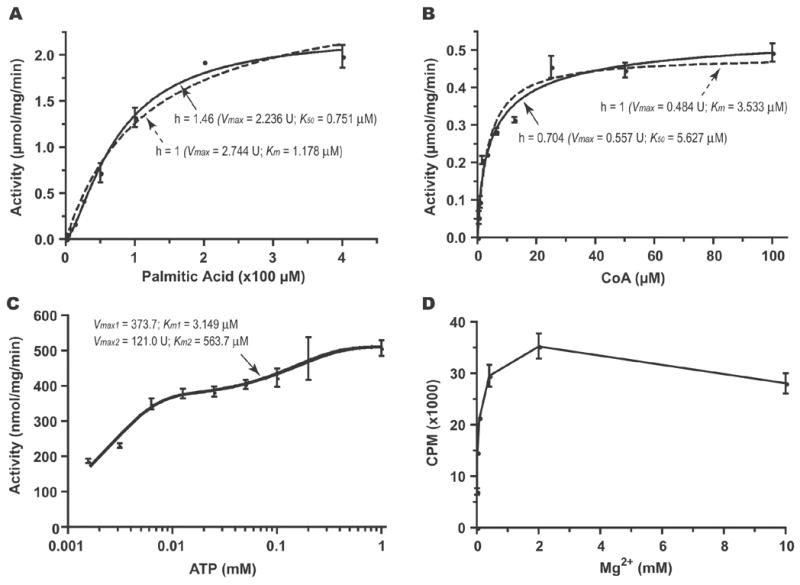

The apicomplexan Cryptosporidium parvum possesses a unique 1,500-kDa polyketide synthase (CpPKS1) comprised of 29 enzymes for synthesizing a yet undetermined polyketide. This study focuses on the biochemical characterization of the 845-amino acid loading unit containing acyl-[ACP] ligase (AL) and acyl carrier protein (ACP). The CpPKS1-AL domain has a substrate preference for long chain fatty acids, particularly for the C20:0 arachidic acid. When using [3H]palmitic acid and CoA as co-substrates, the AL domain displayed allosteric kinetics towards palmitic acid (Hill coefficient, h = 1.46, K50 = 0.751 μM, Vmax = 2.236 μmol mg−1 min−1) and CoA (h = 0.704, K50 = 5.627 μM, Vmax = 0.557 μmol mg−1 min−1), and biphasic kinetics towards adenosine 5′-triphosphate (Km1 = 3.149 μM, Vmax1 = 373.3 nmol mg−1 min−1, Km2 = 121.0 μM, and Vmax2 = 563.7 nmol mg−1 min−1). The AL domain is Mg2+-dependent and its activity could be inhibited by triacsin C (IC50 = 6.64 μM). Furthermore, the ACP domain within the loading unit could be activated by the C. parvum surfactin production element-type phosphopantetheinyl transferase. After attachment of the fatty acid substrate to the AL domain for conversion into the fatty-acyl intermediate, the AL domain is able to transfer palmitic acid to the activated holo-ACP in vitro. These observations ultimately validate the function of the CpPKS1-AL-ACP unit, and make it possible to further dissect the function of this megasynthase using recombinant proteins in a stepwise procedure.

Keywords: Apicomplexa, Cryptosporidium parvum, Polyketide synthase, Acyl ligase, Acyl carrier protein, Phosphopantetheinyl transferase, Linetics, Triacsin C

1. Introduction

Polyketides are a large class of structurally diverse natural secondary metabolites produced by bacteria, fungi, sponges, insects, and plants. Along with their semi-synthetic derivatives they now play a vital role as human and veterinary medicine therapeutic agents and agricultural agents including antibiotic, anticancer, antiparasitic, immunosuppressant and insecticide compounds (O’Hagan, 1991; Hopwood, 1997; Pereda et al., 1998; Peiru et al., 2005). Other functions include serving as defensive molecules in microbes as well as having a role in organism-to-organism signaling (Rawlings, 1997; Pfeifer and Khosla, 2001; Staunton and Weissman, 2001). Polyketide biosynthesis mechanistically resembles that of fatty acids. Both fatty acid synthases (FASs) and polyketide synthases (PKSs) serve as biochemical assembly lines composed of a series of catalytic domains or discrete enzymes involved in the sequential assembly and modification of acyl groups on the growing chain (Keating and Walsh, 1999). They both catalyze repetitive Claisentype decarboxylative condensations between an acyl thioester and a fatty acid, and both use acyl carrier protein (ACP) as an attachment site for the growing carbon chain. However, polyketides are far more diverse in their final product structures than the free fatty acids typically produced by FAS. The wide variety of polyketide products is mainly due to PKSs being more diverse in the reactions they catalyze as well as in the wide variety of both starter and chain extender units they use, carbon chain length, degree of reduction and/or dehydration, and folding of the final product (Khosla and Zawada, 1996; Hopwood, 1997; Katz, 1997; Khosla, 1997; Cane et al., 1998; Moore and Hertweck, 2002; Caffrey, 2003). The complete cycle of ketoacyl reduction, dehydration and enoyl reduction producing a saturated carbon chain that is observed in FAS may be shortened in PKSs so that a saturated or poly-unsaturated carbon chain is produced containing many keto and hydroxyl groups (Hopwood and Sherman, 1990; Metz et al., 2001). Post-PKS modifications add to the diversity of polyketides as the extended linear carbon chain products are then often glycosylated, acylated, alkylated, oxidated and/or cyclized to form the complex biochemicals that can be used as medical and veterinary therapeutics.

Cryptosporidium parvum is a parasitic protist that infects both humans and animals. It belongs to the Phylum Apicomplexa that contains many important parasites including Plasmodium, Toxoplasma, Babesia, Eimeria and Cyclospora (Zhu et al., 2000a). This parasite possesses two unusual genes that encode giant polypeptides: a 25-kb fatty acid synthase (CpFAS1) and a 40-kb polyketide synthase (CpPKS1). Both genes have previously been sequenced and reported (Zhu et al., 2000b, 2002, 2004). Sequence Information for the CpPKS1 Gene is available in the GenBank database under accession no. AF405554. CpFAS1 has recently been expressed as recombinant individual proteins (as multifunctional units or modules). The activities of most CpFAS1 enzymatic domains have been detected using recombinant proteins, although the endogenous product of CpFAS1 is yet to be elucidated (Zhu et al., 2004). On the other hand, CpPKS1, the first PKS identified from a protist, has yet to be expressed and functionally characterized (Zhu et al., 2002).

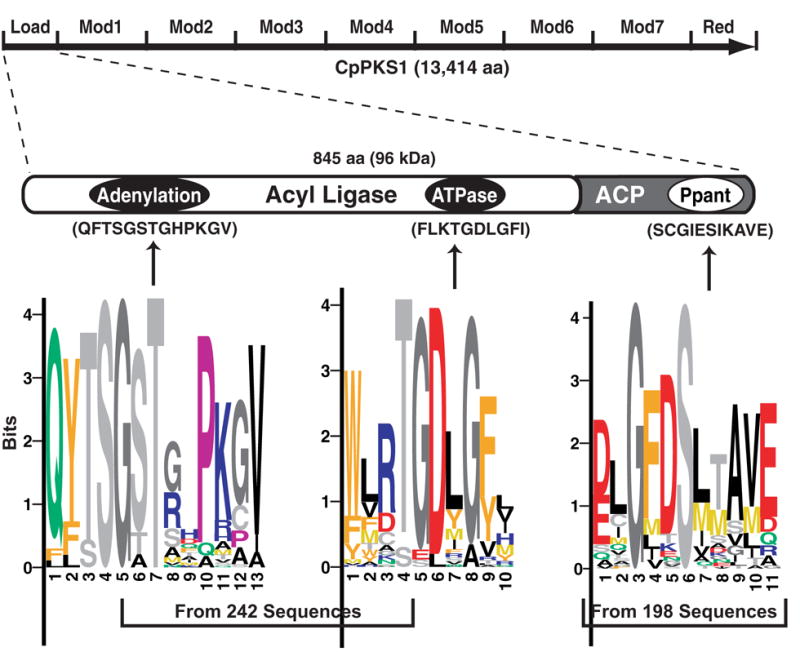

CpPKS1 can be conceptually translated into a single 1,516-kDa polypeptide, in which the predicted 29 enzymatic domains are organized into an N-terminal loading unit, seven internal elongation modules, and a C-terminal reductase terminating domain (Fig. 1) (Zhu et al., 2002). Due to its large size, heterologous expression of the entire CpPKS1 gene would be impractical. To overcome this problem we have decided to use a “divide and conquer” strategy, in which the large CpPKS1 is expressed as individual but multifunctional units or modules for biochemical analysis. Here, we report the expression and biochemical analysis of the CpPKS1 N-terminal loading unit that contains two enzymatic domains: an acyl-[ACP] ligase (AAL) domain for activating and loading substrate and an ACP domain for the attachment of acyl substrates. Although there are few PKSs with a loading unit containing the same domain organization, we believe this is the first study to fully characterize the AL domain contained in this relatively rare loading unit. The detailed substrate preference and catalytic features of the AL domain were determined. We also demonstrated that the ACP domain can be activated by an surfactin production element-type phosphopantetheinyl transferase in C. parvum (CpSFP-PPT), and the AL domain is able to catalyze the attachment of long chain fatty acids to the activated ACP domain.

Fig. 1.

The CpPKS1 loading unit consists of acyl ligase (AL) and acyl carrier protein (ACP) domains. The AL domain contains two highly conserved motifs responsible for the adenylation and ATPase activities. The ACP domain contains the phosphopantetheinyl binding domain (Ppant) for the attachment of a phosphopantetheinyl moiety to the conserved serine reside. Position-specific scoring matrix (PSSM) logos for the three domains were generated from the specified numbers of sequences retrieved from the GenBank™ protein database. Within each logo, the letter(s) represent the respective amino acid position in each motif, whereas the size of each letter represents the relative abundance of the respective amino acid within the sequences used for comparison. Motifs for the three conserved domains in the CpPKS1 loading unit are provided in parentheses for comparison with the PSSM logos. Load = loading unit, Mod = elongation modules, Red = reductase domain.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Enzyme nomenclature

We will follow Nomenclature Committee of IUNMB (NC-IUBMB) recommendations to use “ligase” to replace “synthetase” that catalyzes “synthetic reactions with concomitant hydrolysis of a nucleoside triphosphate” (see NC-IUBMB Newsletter (http://www.chem.qmul.ac.uk/iubmb/newsletter/misc/synthase.html#1). The acyl ligase (AL) may represent either a discrete acyl-CoA ligase (ACL) or the acyl-[ACP] ligase domain (AAL) in FAS/PKS, in which ACL and acyl-CoA synthetase (ACS) are in fact interchangeable.

2.2. Protein motif analysis

The CpPKS1 loading unit AL and ACP domains were used separately as queries to search protein databases including all non-redundant GenBank coding sequence translations, RefSeq Proteins, Protein Data Bank, SwissProt, Protein Information Resource and Protein Research Foundation at the National Center for Biotechnology Information using the PSI-BLAST program (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST) (Altschul et al., 1997). Four iterative PSI-BLAST searches were performed for both the AL and ACP domains with the BLOSUM62 matrix (penalties for existence and extension = 11 and 1, respectively). Only those sequences with E-values less than 1 × 10−4 were used for multiple sequence alignments with the ClustalW algorithm using MacVector v9.0 (Accelrys Software Inc.) and observable mistakes in alignments were corrected upon visual inspection. Conserved motifs from each domain were determined from the alignments and blocks logos were obtained from position-specific scoring matrices (PSSM) from the BLOCKS server (http://blocks.fhcrc.org/blocks) (Henikoff et al., 1995).

2.3. Amplification and cloning of DNA construct

The 2,545-bp CpPKS1 loading unit (CpPKS1-AL-ACP) was amplified from C. parvum (Iowa strain) genomic DNA (gDNA) with high-fidelity Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene) using primers CpPKS1-Load-F (5’ aga gga tcc ATG AAT AGT AGT AAA CCT GAG TAT G 3’) and CpPKS1-Load-R (5’ aga gga tcc TTA GTG AGC ATT TAT TCC AGA AAT AAC 3’) (lower cases represent artificial BamHI linkers). The amplified product was purified from a 1% agarose gel using a MinElute gel extraction kit (Qiagen) and first cloned into the pCR-XL-TOPO vector (Invitrogen). Plasmids were isolated from positive colonies, followed by restriction digestion analysis and sequencing to confirm their identities. Plasmids containing correct inserts were then digested with BamHI to release the CpPKS1-AL-ACP insert, purified from agarose gel, ligated into the pMAL-c2X expression vector (New England Biolabs), and transformed into Escherichia coli Mach1 cells (Invitrogen). Positive colonies were selected via PCR using CpPKS1-Load-F and LacZ-R (5’ CGC CAG GGT TTT CCC AGT CAC GAC 3’, an antisense primer downstream from the multiple cloning site), as well as multi-restriction enzyme digestions to determine appropriate orientation.

2.4. Expression and purification of protein

Plasmid DNA containing the correctly oriented insert (pMAL-c2X-CpPKS1-AL-ACP) was transformed into chemically competent E. coli Rosetta cells (Novagen) and plated onto solid Luria-Bertani (LB) medium containing ampicillin (50 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (34 μg/ml), and glucose (2 mM). After incubation overnight at 37°C, a single colony of transformed bacteria was first inoculated into 25 ml LB media containing the appropriate antibiotics and glucose, and grown overnight at 30°C in a shaking incubator. The overnight cultures were diluted 1:10 with fresh medium and allowed to grow for approximately 5 h at 25°C until the OD600 reached ~ 0.5. At this time, isopropyl-1-thio-β-D galactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to a final concentration of 0.5 mM to induce protein expression, and cells were grown an additional 12 h at 16°C. The bacteria were collected by centrifugation, resuspended in 50 ml TNE buffer (20 mM Tris.HCl pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail optimized for bacteria (Sigma) and subjected to mild sonication on ice. Insoluble debris was removed by centrifugation. The MBP-CpPKS1-AL-ACP fusion protein was purified using amylose resin-based affinity chromatography according to the manufacturer’s standard protocol (New England Biolabs).

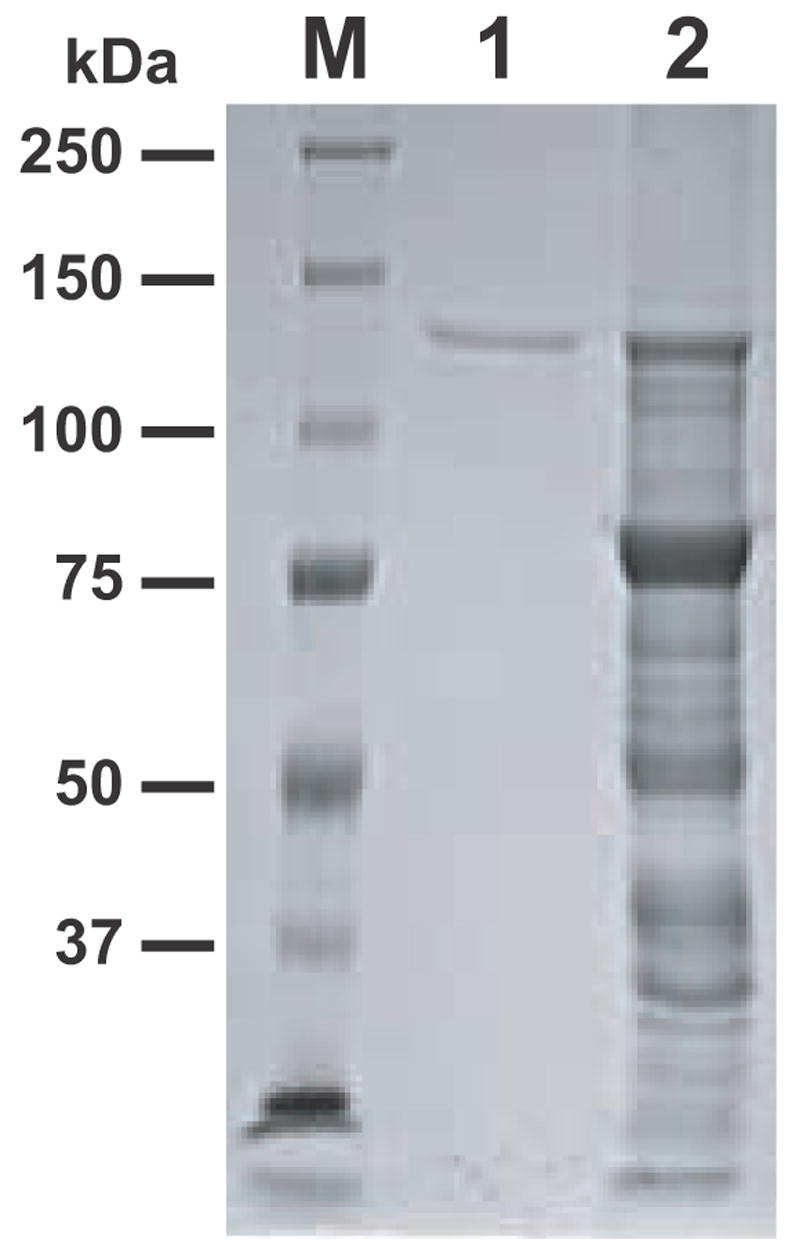

SDS-PAGE analysis of the purified protein revealed two distinct bands; one corresponding to full-length MBP-fused CpPKS1-AL-ACP (~138-kDa) and another at approximately 80-kDa. The full length fusion protein was then extracted from a glycine-based, 6% native-PAGE gel using a previously reported protocol with minor modifications (Cohen and Chait, 1997). Briefly, the affinity-purified protein was first concentrated using a membrane based VivaSpin concentrator with a 100-kDa cut-off (VivaScience) and fractionated with a 6% native-PAGE gel. The protein bands were visualized using a zinc stain kit (Bio-Rad), individually cut from the gel, and destained in 1.5 mL microtubes for a total of 30 min and then washed with PBS. The gel slices were thoroughly crushed, mixed with PBS (pH 7.2) that slightly covered the crushed gel, centrifuged at 20,000 g for 30 min at 4°C and the supernatant retrieved. This was repeated three times and after pooling the sample a small aliquot was allocated for SDS-PAGE analysis. The full length MBP-CpPKS1-AL-ACP fusion protein was then extensively dialyzed in PBS (pH 7.2) and concentrated using the VivaSpin concentrator. Protein concentrations were determined by a Bradford colorimetric method using BSA as a standard.

2.5. Acyl-[ACP] ligase (AL) activity

The AL domain is proposed to catalyze the thioesterification between a fatty acid and the adjacent ACP domain. However, we have previously shown that the AL domain from evolutionarily related CpFAS1 is able to use Co-enzyme A (CoA) as a receiver, which permits the detailed enzyme kinetic analysis for the AL domain (Zhu et al., 2004). In this study, we found that the CpPKS1-AL domain was also able to catalyze the thioesterification of palmitic acid with CoA. A typical reaction (100 μl) was composed of 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 2 mM EDTA, 5 mM adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP), 300 μM CoA, 2 mM Triton X-100, 1 mM KF, 20 μM [9,10-3H(N)]palmitic acid and 20 ng MBP-CpPKS1-AL-ACP fusion protein. After incubation at 37°C for 10 min, reactions were stopped with the addition of 125 μl of Dole’s solution (40:10:1 = isopropanol/heptane/1 M H2SO4) and 50 μl of water, followed by a strong vortex to thoroughly mix. A heptane extraction method was then used by the addition of 500 μl of heptane immediately followed by vigorous mixing and centrifugation at 10,000 g for 2 min. The upper organic phase was removed, while the lower aqueous phase containing the radiolabelled palmitoyl-CoA was washed three more times with heptane containing 4 mg/ml unlabelled (cold) palmitic acid (to chase out radioactive palmitic acid) and once more with heptane only. Next, 75 μl of the washed aqueous phase was mixed with 5 ml of scintillation fluid and the radioactivity was counted in a Beckman Coulter LS 6000SE counter. Enzyme kinetics values for this reaction were calculated from a Lineweaver-Burk plot with substrate concentrations ranging from 0.39 to 400 μM. Each reaction was assayed at least in duplicate. The MBP-tag was used to replace MBP-CpPKS1-AL-ACP for background subtraction as a control at each concentration.

The kinetics for the AL domain were similarly assayed, using varying amounts of CoA (0.39 – 100 μM), ATP (0.78 – 1,000 μM), and MgCl2 (0.032 – 10 mM). We also tested whether the CpPKS1-AL domain could use guanosine triphosphate (GTP) or uridine triphosphate (UTP) (each at 5 mM) to replace ATP as alternate energy sources. Additionally, the inhibitory effects of triacsin C (2 – 40 μM) on the AL domain were analyzed under the same reaction conditions.

2.6. Substrate specificity of the AL domain

A substrate competition assay was employed to determine substrate specificity as previously described (Zhu et al., 2004). Briefly, 20 μM of various unlabelled (cold) even carbon saturated fatty acids from C2:0 to C30:0 were added to the reaction mixture to compete with the same molar amount of [3H]palmitic acid under the same conditions for the typical assay. The same heptane extraction method was performed to measure the resulting amount of radiolabelled palmitoyl-CoA in the aqueous phase. The resulting data were plotted as the percent radioactivity in each assay compared to the reactions containing only [3H]palmitic acid. Controls in all experiments included reactions with no protein present and 20 ng MBP only for background subtractions. At least three independent assays were performed with at least three replicates for each reaction.

2.7. Phosphopantetheinylation of the ACP domain

Because recombinant ACP domains from CpFAS1 could only be expressed in the inactive apo form (Zhu et al., 2004; Cai et al., 2005), we suspected that the bacterial host cells were also unable to phosphopantetheinylate the ACP domain in the CpPKS1 loading unit. Therefore, we wanted to test the ability of recombinant C. parvum SFP-type phosphopantetheinyl transferase (CpSFP-PPT) to activate the apo-ACP domain of the CpPKS1 loading unit. CpSFP-PPT has been previously expressed as an S-tag-fused protein from an artificially synthesized DNA fragment, and its capacity in activating the ACP domains from CpFAS1 has been studied in detail (Cai et al., 2005). In this assay, a 40 μl reaction consisting of 75 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 10 mM MgCl2, 4 μg MBP-CpPKS1-AL-ACP, 400 ng CpSFP-PPT and 40 μM [1-14C]acetyl-CoA was used so that the attachment of the phosphopantetheinyl group could be visualized by autoradiography. Reactions were started with the addition of the radioactive acetyl-CoA, and incubated at 37°C for 45 min. The entire reaction was then subjected to 6% SDS-PAGE and visualized from dried gels using a FUJI BAS 1800 II PhosphorImager. As a control, reactions also included no protein, MBP only or no CpSFP-PPT, to ensure that the MBP fusion tag has no activity and the ACP domain cannot be activated in the absence of CpSFP-PPT.

2.8. AL domain mediated transfer of long chain fatty acid to holo-ACP

After determining that CpSFP-PPT was able to activate the apo-ACP domain in the recombinant CpPKS1-AL-ACP protein, we next tested whether the AL domain was able to transfer palmitic acid to the adjacent activated holo-ACP by two sequential reactions. First, the ACP domain was activated by CpSFP-PPT using the same reaction conditions as above, except unlabelled CoA (40 μM) was used to replace radioactive acetyl-CoA, so that only the phosphopantetheinyl moiety (rather than the acetylated moiety) would be transferred to the ACP. After free CoA was removed from the reaction using a Zeba desalting spin column (Pierce), a 40 μl sample was then used in a second reaction (65 μl) containing 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, 5 mM ATP, 2 mM Triton X-100, 1 mM KF and 20 μM [3H]palmitic acid. The reaction was incubated at 37°C for 45 min, fractionated by 6% SDS-PAGE and visualized with autoradiography as before. Similar controls were included as described for the phosphopantetheinylation of the ACP domain section.

3. Results

3.1. The CpPKS1 loading unit contains motifs characteristic to the ACL family and ACPs

Of the 13,414-amino acid CpPKS1, the loading unit comprises only 845 amino acids (Fig. 1). The AL domain shares sequence similarities with many other adenylate-forming enzymes, particularly the adenosine monophosphate (AMP)-forming, long chain fatty acyl-CoA ligases (also termed as fatty acyl-CoA synthetase, EC 6.2.1.3) (Black et al., 1997). Like the AL domain in some PKSs, the CpPKS1-AL domain contains both adenylation and ATPase motifs (Zhu et al., 2000b, 2002) (Fig. 1). The AL domain adenylation core sequence differs by only a few amino acids from that of the typical AMP-binding motif (mXXTSGtTGXPK) (Tang et al., 1998), but still shares a substantial degree of similarity as determined by PSSM analysis of 242 sequences. The second motif that appears to be more restricted to the ACL family is the ATPase motif. The ATPase motif’s core sequence (TGD) is highly conserved among all enzymes of this type as can be observed by the PSSM analysis of the same 242 sequences. The diversity of the 242 analyzed sequences is as follows: bacteria, 93%; fungi, 2.5%; plants, 2.1%; protists and insects, each 1.2%.

Similar to all other ACPs, the ACP domain in the CpPKS1 loading unit contains the 4’-phosphopantetheinyl-binding cofactor box (GxDS[I/L]) as defined by the PSSM analysis of 198 ACP sequences (bacteria, 92.9%; fungi, 5.6%; protists, 1.5%). However, this ACP domain appears to be one of very few ACP sequences analyzed where a glutamate (E) replaces the aspartate (D) in the core sequence. Although the function of the ACP domain is not expected to differ, it is interesting that this is one of few ACPs with this set of amino acids surrounding the conserved serine residue.

3.2. Expression and purification of recombinant CpPKS1-AL-ACP

The CpPKS1 loading unit was strategically engineered into and expressed in the pMAL-c2X expression vector as a 138-kDa MBP-fusion protein. The affinity of MBP for maltose allows for an easy amylose resin-based affinity chromatography purification method which usually provides for a rapid one-step purification of the fusion protein (Kellermann and Ferenci, 1982). However, regardless of the expression parameters used (i.e. growth/induction time, temperature and IPTG concentration) for CpPKS1-AL-ACP, we always observed two major bands when purified using amylose resin-based affinity chromatography. We observed a band at the size of the predicted Mr (138-kDa), but we also observed a stronger band at ~80-kDa (Fig. 2, lane 2) that may represent premature termination of translation or degradation of the protein of interest. For better characterization of enzyme kinetics, the 138-kDa protein was isolated to homogeneity using a modified method for eluting proteins from PAGE gels (Cohen and Chait, 1997) (Fig. 2, lane 1), and used in subsequent analyses. For each 1 L culture used for protein expression, we obtained an average of ~4 mg/L of protein when purified utilizing affinity resin-based chromatography. Due to the presence of protein bands other than the protein of interest being visualized using SDS-PAGE, we estimated that the 138-kDa fusion protein was approximately 7.71% (0.316 mg/L) of the total protein purified from affinity chromatography. After gel extraction of the concentrated affinity purified protein sample, we obtained an average of 0.241 mg/L of the single-banded full-length fusion protein shown in Fig. 2, lane 1. This corresponds to a ~76% recovery of the full length 138-kDa fusion protein.

Fig. 2.

SDS-PAGE analysis of the maltose binding protein-CpPKS1-acyl ligase-acyl carrier protein fusion protein purified by a two-step approach (amylose resin-based affinity chromatography and PAGE gel extraction). The full-length fusion protein (138-kDa) was used in all enzymatic assays. M = protein marker, lane 1 = full length fusion protein from gel purification, lane 2 = amylose resin-based affinity purified protein.

3.3. Enzyme kinetics of the AL domain

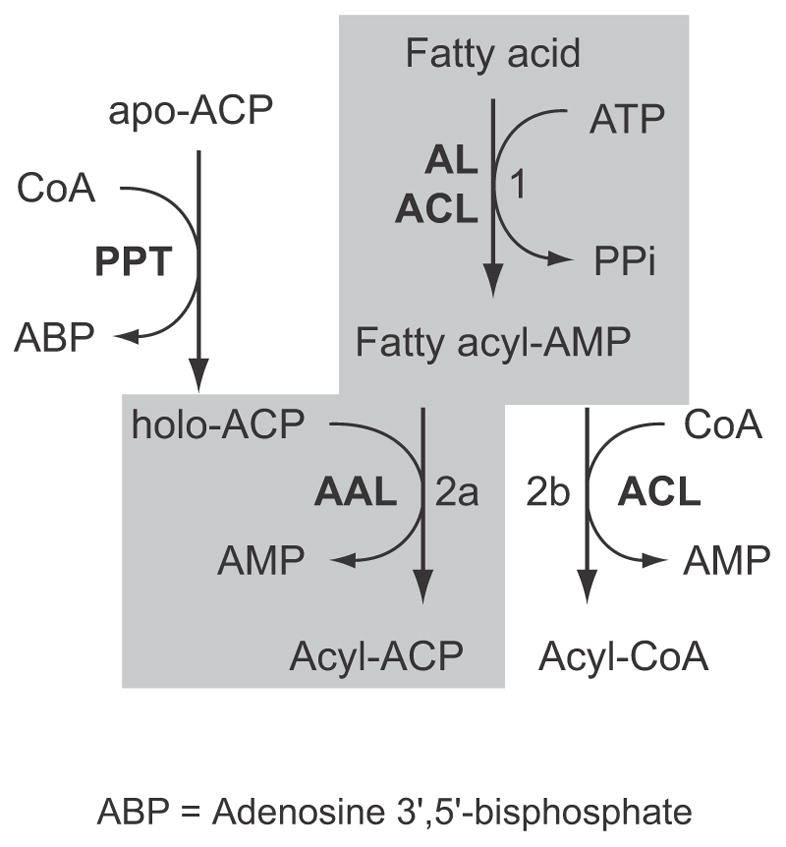

The ACL family catalyzes the formation of a fatty acyl-CoA from a fatty acid substrate, ATP, and CoA in a Mg2+-dependent two-step reaction (Bar-Tana et al., 1973a, 1973b; Black et al., 1997) (Fig. 3). A fatty acyl-adenylate intermediate is formed with the release of pyrophosphate in the first reaction, followed by conversion of the fatty acyl-adenylate to fatty acyl-ACP or acyl-CoA with the release of AMP. Like the AL domain in CpFAS1, the CpPKS1-AL domain was able to use CoA to replace holo-ACP to receive the C16 palmitic acyl chain. Using a heptane extraction-based radioactive assay, we observed that the AL activity towards palmitic acid in general followed Michaelis-Menten kinetics (Km and Vmax values at 1.178 μM and 2.744 μmol mg−1 min−1, respectively) (Fig. 4A, dashed curve labelled with h [Hill coefficient] = 1). However, further analysis indicated that the AL kinetics actually fit better to a sigmoidal curve; co-efficient of determination (R2) = 0.9906 compared with 0.9829 for Michaelis-Menten kinetics (Fig. 4A, solid curve labelled with h = 1.46), indicating the presence of positive cooperativity between the two steps of the overall reaction (i.e., formations of palmitoyl-AMP and palmitoyl-CoA, respectively). Under the consideration of cooperativity, the values for K50 (equivalent to Km) and Vmax were determined at 0.751 μM and 2.236 μmol mg−1 min−1, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Acyl ligase (AL) catalyzes a two-step reaction to activate fatty acids. The first step forms fatty acyl-adenosine monophosphate (AMP) (reaction 1). In second step, acyl-[acyl carrier protein] ligase (AAL) catalyzes the formation of acyl-acyl carrier protein (ACP; reaction 2a), while acyl-CoA ligase (ACL) catalyzes the formation of acyl-CoA ester (reaction 2b). However, when HSCoA is present, AAL may also catalyze the formation of acyl-CoA, thus allowing the detection of its activity by a simple heptane extraction assay. The synthesis of holo-ACP from apo-ACP is catalyzed by phosphopantetheinyl transferase (PPT). ABP = Adenosine 3′,5′-bisphosphate.

Fig. 4.

The activity of the CpPKS1-acyl ligase (AL) domain for catalyzing the formation of palmitoyl-CoA as determined by a heptane extraction assay. A) Allosteric kinetics assayed with various concentrations of palmitic acid indicates the presence of a positive cooperativity in the reaction (Hill coefficient, h = 1.46). B) Allosteric kinetics assayed with various CoA indicates the presence of a small negative cooperativity (h = 0.704). C) Binding kinetics assayed with various concentrations of adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP). The AL domain displayed two-site binding kinetics, suggesting the presence of possible overall biphasic kinetics. D) The AL domain activity is Mg2+-dependent with an optimal concentration at ~2 mM. In all samples, bars represent the S.D. derived from duplicate or triplicate reactions. U = μmol mg−1 min−1.

The kinetic values of the CpPKS1-AL domain using CoA and ATP as substrates were also studied in detail. Using CoA as a substrate, the AL domain displayed close to typical Michaelis-Menten kinetics (Km and Vmax were 3.533 μM and 0.484 μmol mg−1 min−1, respectively) (Fig. 4B, dashed curve). Nonlinear curve fit using an allosteric enzyme model was able to give a slightly better fitted curve (R2 = 0.9701 vs. 0.957), suggesting the presence of weak negative cooperativity (Fig. 4B, solid curve, h = 0.704). Under the consideration of cooperativity, the K50 and Vmax values were determined at 5.627 μM and 0.557 μmol mg−1 min−1, respectively. The AL domain appeared to have relatively strong affinity towards ATP. At ATP concentrations from 0.78 μM to 1 mM, the AL domain fit well with a biphasic kinetics model. Using this model (i.e. Observed Total Velocity (v) = v1 + v2 = Vmax1*X/(Km1+X) + Vmax2*X/(Km2+X)), the AL kinetic values for ATP were determined as Km1 = 3.149 μM, Vmax1 = 373.7 nmol mg−1 min−1, Km2 = 563.7 μM, Vmax2 = 121.0 nmol mg−1 min−1 (Fig. 4C). The AL domain also fit the Michaelis-Menten model, although not as strongly (R2 = 0.9472 vs. 0.9664 for the biphasic model) and displayed kinetics similar to the first phase (Km = 3.916 μM, Vmax = 543.8 nmol mg−1 min−1).

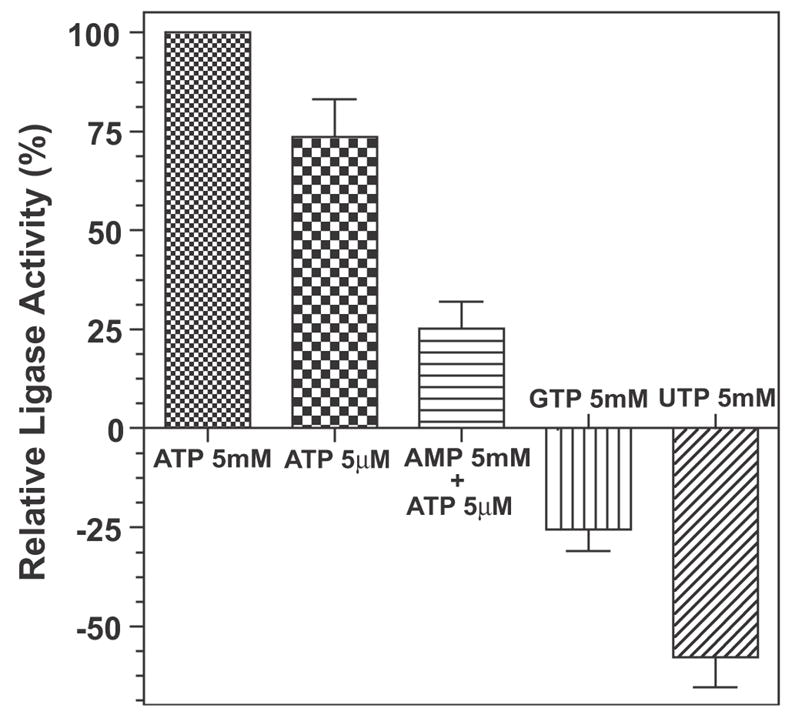

Like the AL domain in the loading unit of CpFAS1 (Zhu et al., 2004), as well as other ALs and ACLs (Black et al., 1997; Matesanz et al., 1999), the activity of CpPKS1-AL can be inhibited by 5 mM AMP when assayed with 5 μM ATP (Fig. 5). In contrast to one ACL in Plasmodium falciparum which can actually utilize GTP or UTP (Matesanz et al., 1999), CpPKS1-AL cannot (Fig. 5). Assay results using GTP and UTP showed similar inhibition to the AL of CpFAS1 (Zhu et al., 2004). Negative data for both of these reactions suggests that, compared with negative controls, these two co-factors might increase the efficiency during the heptane extraction method when extracting palmitic acid (Zhu et al., 2004). The CpPKS1-AL domain is also Mg2+-dependent with an optimal concentration at ~ 2 mM (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 5.

Heptane extraction assays indicate that the activity of the CpPKS1-acyl ligase (AL) domain is adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP)-dependent and can be inhibited by the product adenosine monophosphate (AMP). It cannot use guanosine triphosphate (GTP) or uridine triphosphate (UTP) as an alternative energy source to activate palmitic acid. Bars represent the S.D. derived from duplicate reactions.

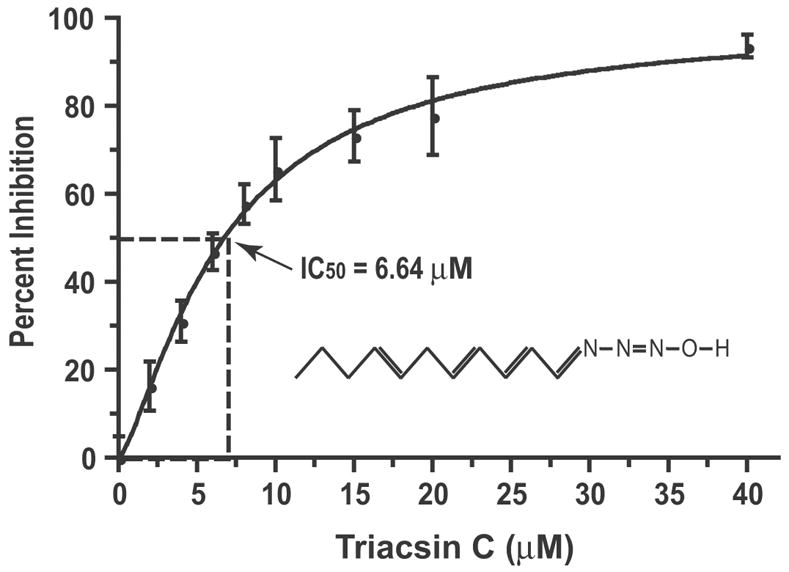

The CpPKS1 activity could be specifically inhibited by triacsin C (1-hydroxy-3-(E,E,E-2’,4’,7’-undecatrienylidine) (Fig. 6). Triacsin C is a fungal metabolite that resembles polyunsaturated fatty acids and can differentially inhibit various ACLs (Fig. 6, inset) (Omura et al., 1986; Hartman et al., 1989; Kim et al., 2001). The observed IC50 for triacsin C to inhibit the thioesterification of palmitic acid with CoA by CpPKS1-AL was 6.64 μM (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Inhibitory effect of Triacsin C (structure depicted in the inset) on the activity of the CpPKS1-acyl ligase (AL) domain as measured by the incorporation of [3H]palmitic acid into palmitoyl-CoA. Bars represent the S.D. derived from duplicate reactions.

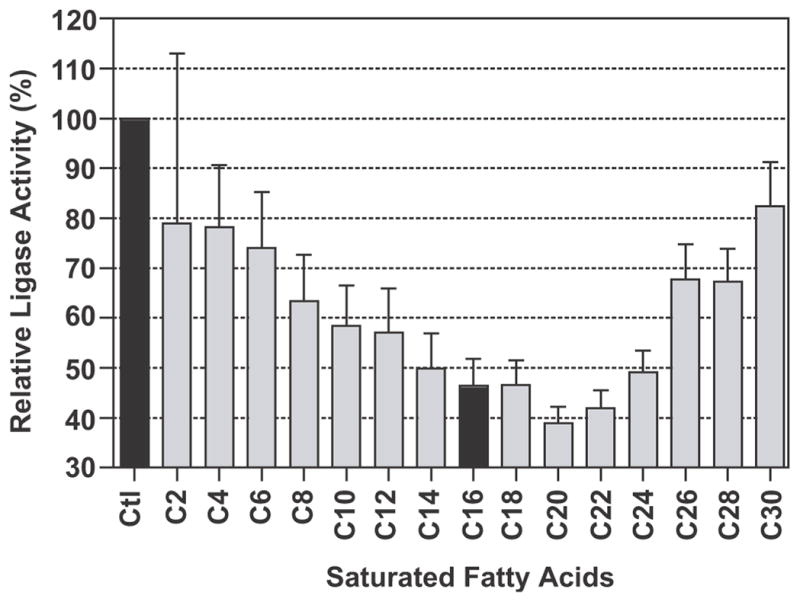

3.4. CpPKS1-AL prefers long chain fatty acids

The substrate specificity for CpPKS1-AL was determined using a wide range of even carbon saturated fatty acids (C2:0 – C30:0) to compete with the same molar amount of [3H]palmitic acid. In this competition assay, the CpPKS1-AL domain displayed the highest affinity for arachidic acid (C20:0), with gradually reduced activities for other fatty acids with chain lengths shorter or longer than C20 (Fig. 7). Although long chain fatty acids (C14 to C24) are favorite substrates, it appears that CpPKS1-AL may also utilize a wide range of other fatty acids from short to very long chain fatty acids, since all tested fatty acids showed some degree of displacement of activity towards to palmitic acid (Fig. 7). However, it remains to be determined whether the short chain (C2 and C4) or very long chain (C30) fatty acids may truly serve as endogenous substrates for CpPKS1-AL as these fatty acids could only displace ~20% of the activity while competing with palmitic acid.

Fig. 7.

Substrate competition assay using the same molar amount (20 μM) of unlabelled fatty acids from C2:0 to C30:0 to compete with [3H]palmitic acid. Values indicate the percent activity of the formation of [3H]palmitoyl-CoA relative to the positive control containing radioactive palmitic acid only (Ctl). The value obtained for C16 (indicated in black) indicates that [3H]palmitoyl-CoA was formed by approximately equal amounts of both radiolabelled and non-radiolabelled palmitic acid. Bars represent the S.D. derived from triplicate reactions.

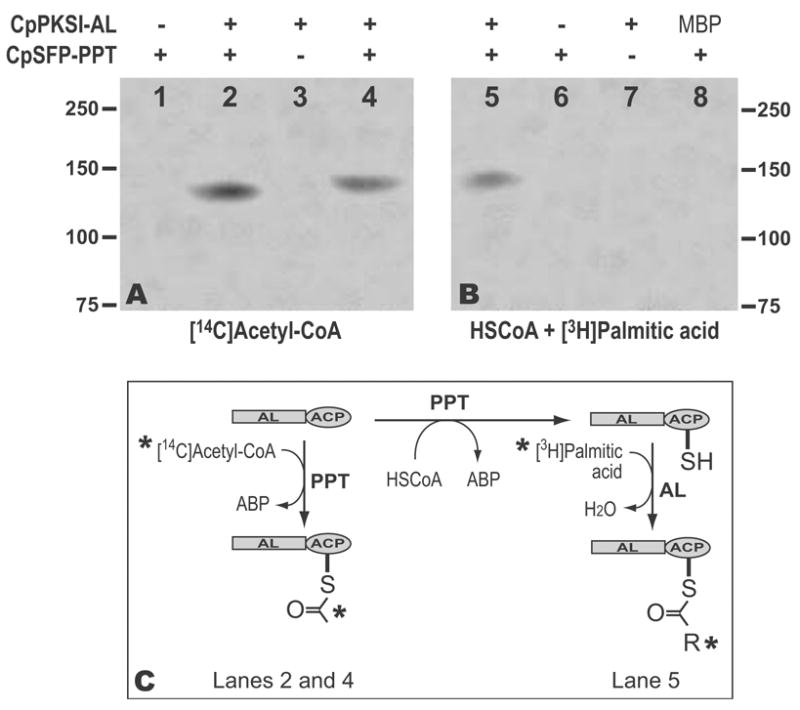

3.5. CpPKS1-AL is capable of transferring fatty acid to the adjacent ACP domain in vitro

A two-step approach was employed to investigate the transfer of fatty acid to the ACP domain. In step one, the apo-ACP domain within the recombinant CpPKS1 loading unit was activated by CpSFP-PPT. We first confirmed that CpSFP-PPT was able to transfer the phosphopantetheinyl moiety from [14C]acetyl-CoA to the ACP domain within the loading unit by autoradiography (Fig. 8A, lane 2). The transfer of the radioactive moiety from [14C]acetyl-CoA to ACP could be chased out when same amount of cold acetyl-CoA was included in the reaction (Fig. 8A, lane 4), which indicates that the radioactive signal was not due to the potential non-specific binding of recombinant proteins to acetyl-CoA. We then used CpSFP-PPT to synthesize the holo-ACP domain using unlabelled HSCoA as a donor for the phosphopantetheinyl moiety. In step two, the CpPKS1-AL domain-mediated attachment of [3H]palmitic acid to the holo-ACP domain was demonstrated by autoradiography (Fig. 8B). No radioactivity was observed in any negative controls (e.g. CpSFP-PPT only, CpPKS1 loading unit only, and PPT + MBP), indicating that only the activated ACP domain within the loading unit received palmitic acid and both CpSFP-PPT and the AL domain were required for this activity (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Activation of the acyl carrier protein (ACP) domain by Cp-surfactin production element-phosphopantetheinyl transferase (CpSFP-PPT), and the CpPKS1-AL-mediated transfer of palmitic acid to the activated ACP. A) Autoradiography showing the CpSFP-PPT catalyzed activation of the ACP domain within the loading unit (CpPKS1-acyl ligase (AL)-ACP) by receiving a radioactive phosphopantetheinyl moiety from [14C]acetyl-CoA (lanes 2 and 4). Reactions in lane 2 received all radioactive acetyl-CoA, while lane 4 received a mixture of same amount of radioactive and non-radioactive substrate. No radioactivity was detected in lanes 1 and 3 that contained only CpSFP-PPT or the loading unit, respectively. B) Autoradiography showing the transfer of the [3H]palmitoyl chain to the activated ACP domain (lane 5). Unlabelled HSCoA was used here for activating the ACP domain by CpSFP-PPT. No radioactivity was detected in reactions containing only CpSFP-PPT (lane 6), the loading unit (lane 7), or when maltose binding protein (MBP) was used to replace loading unit (lane 8). C) Diagram showing the reactions detected by autoradiography in A and B. Asterisks indicate the radioactive molecules.

4. Discussion

CpPKS1 is the first PKS identified from a protist (protozoan) (Zhu et al., 2002). It appears to share the same evolutionary ancestor with CpFAS1, based on the overall sequence similarities and phylogenetic evidence inferred from the AT and KS domains (Zhu et al., 2002; Zhu, 2004). Among other apicomplexans that possess a plastid and associated Type II FAS, Plasmodium falciparum lacks Type I FAS or PKS, whereas Toxoplasma gondii and Eimeria tenella have both Type I FAS and PKS present in their genomes (data not shown, but they can be easily identified by BLAST-searching the two parasite genome databases using CpFAS1 and CpPKS1 as queries at http://ToxoDB.org and http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/E_tenella). More recently, PKS genes closely related to CpPKS1 have been reported from the dinoflagellates (Snyder et al., 2003, 2005), suggesting that Type I FAS or PKS might have been present before the species expansion of Alveolata.

Among these two C. parvum megasynthases, preliminary biochemical analysis using recombinant proteins has indicated that CpFAS1 may be involved in the elongation, rather than the de novo synthesis, of fatty acids (Zhu, 2004; Zhu et al., 2004). However, nothing was previously known about the biochemical features of CpPKS1. Furthermore, no previous studies have clearly evaluated the biochemical features of this type of loading domain among various other PKSs. The CpPKS1 product(s) and biological roles remain to be elucidated. The present study focuses on delineating the biochemical features and substrate preference for the CpPKS1 loading unit, which serves as a first, but essential, step for elucidating the functional role(s) of this megasynthase.

We first expressed the loading unit containing AL and ACP domains as an MBP-fused protein and purified the fusion protein to homogeneity. Like the CpFAS1-AL domain, the CpPKS1-AL domain was able to utilize HSCoA to replace ACP for receiving the fatty acyl chain, thus allowing the detailed analysis of enzyme kinetics. It is interesting that the CpPKS1-AL domain displayed allosteric kinetics when using palmitic acid as a substrate (h = 1.46 [Fig. 4A]). This feature has yet to be reported among other ACLs, probably due to the fact that the enzyme kinetics might also be well analyzed by a simple Michaelis-Menten algorithm. Although a detailed mechanism behind the allosteric kinetics remains to be elucidated, it implies the presence of positive cooperativity between the two reactions catalyzed by AL (i.e., the formations of palmitoyl-AMP and palmitoyl-CoA). The kinetics for the AL domain to use ATP is also intriguing. It follows both Michaelis-Menten kinetics and, to a greater extent, two-site binding kinetics, suggesting possible biphasic kinetics, for which the mechanism has yet to be determined. It is possible that two forms of recombinant CpPKS1 loading unit were present in purified proteins, which have different affinities for ATP.

Substrate competition assays have shown that the CpPKS1-AL domain has a general preference for long chain fatty acids, particularly to arachidic acid. This implies that CpPKS1 may be able to add a polyketide chain (likely 14 carbons due to the presence of seven elongation modules) to a fatty acyl precursor. Although the CpPKS1-AL domain may effectively use various fatty acids, its true substrate(s) may be limited by the availability of fatty acids in the parasite cells. Due to the lack of Type II FAS in C. parvum, together with the fact that CpFAS1 prefers palmitic acid as its substrate, this protist is unlikely to be capable of synthesizing fatty acids de novo, thus it may have to rely on the uptake of fatty acids (both saturated and unsaturated) from host cells or the intestinal lumen to supply substrates for CpPKS1 and CpFAS1. On the other hand, it is possible that other types of substrates, such as polyketides, may be used by CpPKS1. However, this is less likely since this parasite lacks any other PKS genes to make precursors for CpPKS1 and the host cells or intestinal lumen are not reliable sources for polyketides. Nonetheless, the profile of substrate preference provides us with important information in selecting substrates for the reconstitution of entire reactions catalyzed by CpPKS1 in the future.

CpPKS1 contains eight ACP domains (one in the loading unit and seven at the end of each elongation module), while CpFAS1 contains four ACP domains. It appears that all of these ACP domains need to be activated by the addition of a prosthetic phosphopantetheinyl moiety, which is catalyzed by PPT. Cryptosporidium possesses one single SFP-type PPT (CpSFP-PPT) that was able to activate the ACP domains in CpFAS1 (Cai et al., 2005). Here we have shown that CpSFP-PPT was able to activate the ACP domain in CpPKS1 (Fig. 8A), indicating that this single parasite PPT may be responsible for activating the ACP domains in both CpFAS1 and CpPKS1.

Upon the activation of the ACP domain within the CpPKS1 loading unit, the function of the AL domain to transfer an acyl chain to the ACP was ultimately validated by autoradiography (Fig. 8B). This demonstrates that the ACP domains in all CpPKS1 modules may also be activated after they are expressed as fusion proteins, thus permitting the future reconstitution of polyketide chain elongation and release in vitro using recombinant CpPKS1 modules and units.

Acknowledgments

We thank Xiaomin Cai and S. Dean Rider for their generous technical assistance. This research was supported by a grant (R01 AI44594) from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Tana J, Rose G, Brandes R, Shapiro B. Palmitoyl-coenzyme A synthetase. Mechanism of reaction Biochem J. 1973a;131:199–209. doi: 10.1042/bj1310199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Tana J, Rose G, Shapiro B. Palmitoyl-coenzyme A synthetase. Isolation of an enzyme-bound intermediate Biochem J. 1973b;135:411–416. doi: 10.1042/bj1350411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black PN, Zhang Q, Weimar JD, DiRusso CC. Mutational analysis of a fatty acyl-coenzyme A synthetase signature motif identifies seven amino acid residues that modulate fatty acid substrate specificity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4896–4903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.8.4896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffrey P. Conserved amino acid residues correlating with ketoreductase stereospecificity in modular polyketide synthases. Chembiochem. 2003;4:654–657. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X, Herschap D, Zhu G. Functional characterization of an evolutionarily distinct phosphopantetheinyl transferase in the apicomplexan Cryptosporidium parvum. Eukaryot Cell. 2005;4:1211–1220. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.7.1211-1220.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cane DE, Walsh CT, Khosla C. Harnessing the biosynthetic code: combinations, permutations, and mutations. Science. 1998;282:63–68. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5386.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SL, Chait BT. Mass spectrometry of whole proteins eluted from sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels. Anal Biochem. 1997;247:257–267. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman EJ, Omura S, Laposata M. Triacsin C: a differential inhibitor of arachidonoyl-CoA synthetase and nonspecific long chain acyl-CoA synthetase. Prostaglandins. 1989;37:655–671. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(89)90103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henikoff S, Henikoff JG, Alford WJ, Pietrokovski S. Automated construction and graphical presentation of protein blocks from unaligned sequences. Gene. 1995;163:GC17–26. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00486-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood DA, Sherman DH. Molecular genetics of polyketides and its comparison to fatty acid biosynthesis. Annu Rev Genet. 1990;24:37–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.24.120190.000345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood DA. Genetic Contributions to Understanding Polyketide Synthases. Chem Rev. 1997;97:2465–2498. doi: 10.1021/cr960034i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz L. Manipulation of Modular Polyketide Synthases. Chem Rev. 1997;97:2557–2576. doi: 10.1021/cr960025+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating TA, Walsh CT. Initiation, elongation, and termination strategies in polyketide and polypeptide antibiotic biosynthesis. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 1999;3:598–606. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(99)00015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellermann OK, Ferenci T. Maltose-binding protein from Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol. 1982;90(Pt E):459–463. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(82)90171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosla C, Zawada RJ. Generation of polyketide libraries via combinatorial biosynthesis. Trends Biotechnol. 1996;14:335–341. doi: 10.1016/0167-7799(96)10046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosla C. Harnessing the Biosynthetic Potential of Modular Polyketide Synthases. Chem Rev. 1997;97:2577–2590. doi: 10.1021/cr960027u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Lewin TM, Coleman RA. Expression and characterization of recombinant rat Acyl-CoA synthetases 1, 4, and 5. Selective inhibition by triacsin C and thiazolidinediones J Biol Chem. 2001;276:24667–24673. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010793200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matesanz F, Duran-Chica I, Alcina A. The cloning and expression of Pfacs1, a Plasmodium falciparum fatty acyl coenzyme A synthetase-1 targeted to the host erythrocyte cytoplasm. J Mol Biol. 1999;291:59–70. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz JG, Roessler P, Facciotti D, Levering C, Dittrich F, Lassner M, Valentine R, Lardizabal K, Domergue F, Yamada A, Yazawa K, Knauf V, Browse J. Production of polyunsaturated fatty acids by polyketide synthases in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Science. 2001;293:290–293. doi: 10.1126/science.1059593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore BS, Hertweck C. Biosynthesis and attachment of novel bacterial polyketide synthase starter units. Nat Prod Rep. 2002;19:70–99. doi: 10.1039/b003939j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hagan D. The polyketide metabolites. E. Horwood; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Omura S, Tomoda H, Xu QM, Takahashi Y, Iwai Y. Triacsins, new inhibitors of acyl-CoA synthetase produced by Streptomyces sp. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1986;39:1211–1218. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.39.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiru S, Menzella HG, Rodriguez E, Carney J, Gramajo H. Production of the potent antibacterial polyketide erythromycin C in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:2539–2547. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.5.2539-2547.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereda A, Summers RG, Stassi DL, Ruan X, Katz L. The loading domain of the erythromycin polyketide synthase is not essential for erythromycin biosynthesis in Saccharopolyspora erythraea. Microbiology. 1998;144(Pt 2):543–553. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-2-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer BA, Khosla C. Biosynthesis of polyketides in heterologous hosts. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2001;65:106–118. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.1.106-118.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings BJ. Biosynthesis of polyketides. Nat Prod Rep. 1997;14:523–556. doi: 10.1039/np9971400523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder RV, Gibbs PD, Palacios A, Abiy L, Dickey R, Lopez JV, Rein KS. Polyketide synthase genes from marine dinoflagellates. Mar Biotechnol (NY) 2003;5:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10126-002-0077-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder RV, Guerrero MA, Sinigalliano CD, Winshell J, Perez R, Lopez JV, Rein KS. Localization of polyketide synthase encoding genes to the toxic dinoflagellate Karenia brevis. Phytochemistry. 2005;66:1767–1780. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staunton J, Weissman KJ. Polyketide biosynthesis: a millennium review. Nat Prod Rep. 2001;18:380–416. doi: 10.1039/a909079g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang L, Yoon YJ, Choi CY, Hutchinson CR. Characterization of the enzymatic domains in the modular polyketide synthase involved in rifamycin B biosynthesis by Amycolatopsis mediterranei. Gene. 1998;216:255–265. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00338-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu G, Keithly JS, Philippe H. What is the phylogenetic position of Cryptosporidium? Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000a;50:1673–1681. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-4-1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu G, Marchewka MJ, Woods KM, Upton SJ, Keithly JS. Molecular analysis of a Type I fatty acid synthase in Cryptosporidium parvum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000b;105:253–260. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00183-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu G, LaGier MJ, Stejskal F, Millership JJ, Cai X, Keithly JS. Cryptosporidium parvum: the first protist known to encode a putative polyketide synthase. Gene. 2002;298:79–89. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00931-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu G. Current progress in the fatty acid metabolism in Cryptosporidium parvum. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2004;51:381–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2004.tb00384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu G, Li Y, Cai X, Millership JJ, Marchewka MJ, Keithly JS. Expression and functional characterization of a giant Type I fatty acid synthase (CpFAS1) gene from Cryptosporidium parvum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2004;134:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]