Abstract

The Ku protein is involved in DNA double-strand break repair by non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ), which is crucial to the maintenance of genomic integrity in mammals. To study the role of Ku in NHEJ we developed a bicistronic E. coli expression system for the Ku70 and Ku80 subunits. Association of the Ku70 and Ku80 subunits buries a substantial amount of surface area (~9000Å2 [1]), which suggests that herterodimerization may be important for protein stability. N-terminally his6-tagged Ku80 was soluble in the presence, but not in the absence, of bicistronically expressed untagged Ku70. In a 2-step purification, metal chelating affinity chromatography was followed by step-gradient elution from heparin-agarose. Co-purification of equimolar amounts of his6-tagged Ku80 and untagged Ku70 was observed, which indicated heterodimerization. Recombinant Ku bound dsDNA, activated the catalytic subunit of the DNA-dependent kinase (DNA-PKcs) and functioned in NHEJ reactions in vitro. Our results demonstrate that while the heterodimeric interface of Ku is extensive it is nonetheless possible to produce biologically active Ku protein in E. coli.

Keywords: Ku, DNA-PK, non-homologous end-joining, NHEJ

The repair of DNA double strand breaks (DSB) is critical to the maintenance of genomic integrity. The importance of DSB repair is highlighted by the fact that unrepaired DSBs can result in the loss of genetic information, chromosomal translocation and even cell death [2]. An important mechanism for DSB repair is non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) – a homology independent process that is used for the repair DSBs during G0, G1 and early-S phases of the cell cycle [2]. As most of the cells in the mammalian body are terminally differentiated (G0), NHEJ is the major DSB repair pathway used by mammals.

Thus far, six mammalian NHEJ proteins have been described. Central to the DSB repair process is DNA Ligase IV and the proteins XRCC4 and XLF, which are though to function as a complex in the ligation reaction [3–6] (Fig. 1C). Three other proteins – the Ku heterodimer (Fig. 1) and the DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs) – comprise the DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) [7]. Studies employing mouse models have demonstrated that genomic stability depends upon the fidelity of DSB repair through the NHEJ pathway and deficiencies in NHEJ have been linked to cancer [2, 8].

Fig. 1.

Space-filling model of Ku showing Ku70 (red) and Ku80 (gold) generated using Protein Databank accession number 1JEY [1]. A) Side-view. Ring-structure of Ku capable of encircling 2 turns of dsDNA, which passes thru the opening of the preformed ring [1]. B) Top-view. Model in A has been rotated 90º toward the reader to show the large amount of subunit-subunit contact made in this heterodimer. C) Model for mammalian NHEJ. The Ku heterodimer (orange and red) binds DNA ends exposed by a double-strand break, recruits DNA-PKcs and forms the catalytically active protein kinase DNA-PK. DNA Ligase IV is recruited as part of a complex with XRCC4 and XLF and requires inward translocation of Ku to permit binding of DNA Ligase IV complex [17]. End-ligation is catalyzed by DNA Ligase IV.

The DNA end-binding protein Ku protein plays an important role in mammalian NHEJ. Owing to its ring-shaped structure, Ku threads onto exposed DNA termini (Fig. 1A). Following DNA binding by Ku, DNA-PK is assembled and the DNA Ligase IV complex is recruited to the site of the break (Fig. 1C). Highlighting the central role of Ku in NHEJ, deficiencies in Ku have been shown to result in defects in growth, immunoglobulin gene rearrangement recombination, increased sensitivity to ionizing radiation and genomic instability, all of which can lead to tumor formation [2]. Because of the defined link between Ku, genomic stability and cancer we wish to examine the role of Ku in mammalian NHEJ.

Conventional purification of Ku from mammalian cell nuclear extract typically requires 5–6 chromatography steps and yields <10 μg/L of original culture. Purification of recombinant his6-tagged Ku produced in insect cells requires fewer fractionation steps with higher yield (~1 mg/L of original culture [9] and Hanakahi and Cheung unpublished obs.). To study the role of Ku in NHEJ we have established an E. coli expression system for Ku, which will eliminate the need for eukaryotic cell culture. Heterodimerization of the Ku subunits buries ~9000 Å2 [1] (Fig. 1); an unusually large amount when compared with most other 2 subunit multimerization events that typically bury <5000 Å2 [10]. The substantial amount of surface area buried at the Ku heterodimerization interface suggested that folding of Ku in E. coli might be problematic [11]. As we show here, production of Ku in E. coli was possible using bicistronic expression coupled with compensation for sub-optimal codon usage. Purification of Ku from E. coli required only 2 affinity chromatography steps and yielded ~0.47 mg/L of original culture of active protein that bound dsDNA activated DNA-PKcs and functioned in mammalian NHEJ in vitro.

Materials and Methods

Cloning pET70H80

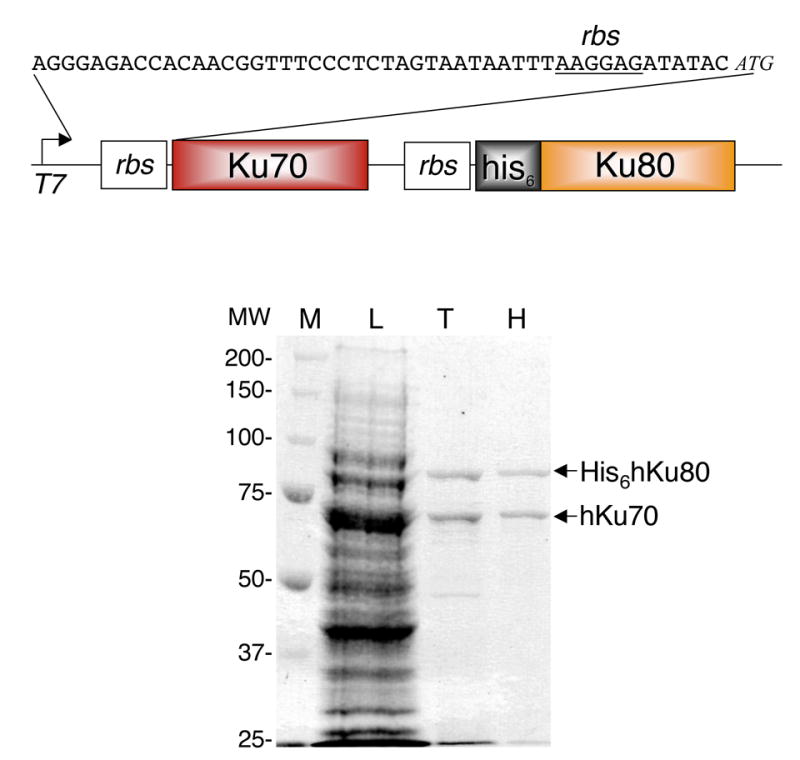

PCR, with primers that incorporated a 5′ ribosome-binding site (RBS) RBS70: 5′-GCACTAGTAATAATTTAAGGAGATATACATGTCAGGGTGGGAG-3′ and Ku703′SpeI: 5′-GCACTAGTTCAGTCCTGGAAGTG-3′, was used to amplify human Ku70 and the product was cloned into the XbaI site of pET14bKu80, which expressed his6-tagged Ku80, (a generous gift from M. Lieber [12]) placing the RBS and Ku70 cDNA downstream of the T7 promoter and upstream of the pET14b RBS and the Ku80 translation start site (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Expression and purification of recombinant Ku. Top) Schematic diagram of bicistronic Ku expression construct pKu70H80 used to express the rKu heterodimer. Bottom) Coomassie stained gel of 50 μg crude bacterial lysate (L) and 630 ng each Talon (T) and Heparin (H) eluate. Details of purification are presented in Materials and Methods and Table 1.

Expression and purification of recombinant Ku70/H80

BL21(DE3)pLysS Rosetta E. coli cells (Novagen) were transformed with the resulting construct, pET70H80, grown in 2 L of Luria Broth (LB) at 37 ºC until the culture reached OD600 1.0. Cells induced at 37 ºC were induced with 0.25 mM IPTG and cultured for 1 hour. Cells induced at low temperatures were chilled on ice to reduce culture temperature to the desired induction temperature then transferred to 25 ºC or 18 ºC and grown for 4 or 18 hours respectively. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (15 min, 4 ºC, 8000 g) and 1 g wet weight of cells was resuspended in 25 ml of lysis buffer (R buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 5% glycerol and 1 mM PMSF) with 1 M NaCl, 0.4 M (NH)4OAc, 10 mM imidazole and 2 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (BME)). BME was used in place of DTT during metal chelating chromatography according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were opened by 3 cycles of freezing on liquid nitrogen and thawing (10 min ice/water slurry) followed by sonication with a Branson Sonifier 450 (20% output at 25% duty cycle 5 x 30 sec.) and insoluble material was removed by centrifugation (30 min, 4 ºC, 25,000 g). 2.5 ml of Talon metal-affinity resin (Clontech) was batch washed twice with lysis buffer and lysate (125 mg) was bound in batch by rocking at 4 ºC for 30 min. After binding, the resin was collected by centrifugation (5 min, 4 ºC, 700 g), washed in batch twice with lysis buffer, twice with R buffer containing 50 mM NaCl, resuspended in 10 ml of R buffer containing 50 mM NaCl, packed into a column and eluted with R buffer containing 50 mM NaCl and 0.5 M imidazole. The eluted protein was loaded directly onto a 1 ml Hi-Trap heparin (GE) column that had been equilibrated in R buffer with 50 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA and 1 mM DTT then eluted with R buffer containing 1 M NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA and 1 mM DTT. Peak fractions were pooled and dialyzed against R buffer with 20% glycerol, 50 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA and 1 mM DTT. Protein concentrations were determined by Bradford assay (BioRad) using BSA as the protein standard.

DNA binding assays

Double-strand DNA cellulose pull-down

20 μl of a 50% native DNA cellulose (SIGMA) slurry was added to 100 μl of 20 nM rKu in HEK buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.6, 0.1 M KHAc, 0.5 mM EDTA), incubated for 1 hour at 4ºC with turning, collected by centrifugation, washed with 3 x 1 ml HEK buffer and resuspended in 2x protein sample buffer. Samples were heated to 100ºC for 5 min, resolved on SDS-PAGE and subject to western transfer. Ku70 was detected with anti-Ku70 rabbit polyclonal antibodies (1:1500 dilution). Ku80 was detected using anti-Ku80 mAb 111 (NeoMarkers) at 1 μg/ml.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Synthetic oliogonucleotide Ku shift Top: 5′-CTGAGAAAACTGTGCGTCTTCGCGGC-AATTGAGAGGCATTCCATTCAC-3′ was radiolabeled, annealed to Ku shift Bottom: 5′-GTGAATGGAATGCCTCTCAATTGCCGCGAAGACGCACAGTTTTCTCAG-3′ and gel purified. Binding to duplex DNA was carried out in 10 μl reactions containing 50 mM Tris, pH 7.75, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 5% glycerol, 100 μg/ml bovine serum albumin, 5 nM 32P-labeled duplex DNA and recombinant Ku as stated for 30 min at room temperature. Complexes were resolved on 5% (29:1 acrylamide:bis) native PAGE in 0.5 x TBE at 2.5 V/min at room temperature. The gel was dried and subject to autoradiography.

DNA-dependent protein kinase assay

The SignaTECT DNA-Dependent Protein Kinase Assay System (Promega) was used according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, reactions are carried out in the presence of gamma-32P ATP and a biotinylated p53 peptide is the protein kinase substrate. After the kinase reaction has been completed the radiolabeled substrate is captured on a streptavidin support, unincorporated 32P is washed away and incorporated 32P was quantified by scintillation counting. DNA-PKcs was purified as previously described [13].

In vitro NHEJ complementation

HeLa whole cell extracts were prepared as described [13]. For low salt Ku-depleted WCE no additional salt was added and the final salt concentration was 0.1 M KOAc. For high salt Ku-depleted WCE NaCl was added to 0.5 M, bringing the final salt composition to 0.5 M NaCl, 0.1 M KOAc. Ku anti-serum (Serotec) was used to immunodeplete Ku. Beads from the 100 μl immunodepletion reactions were washed, resuspended in 100 μl of HEK and used as the immunoprecipitate in complementation experiments. In vitro NHEJ assays were carried out as described [14, 15]. Anti-XRCC4 antibodies (Serotec) and wortmannin (SIGMA) were used as shown. Ku was purified from HeLa cells as described [13].

Ku antibodies

Production of rabbit polyclonal anti-Ku70 antibodies. Full-length human his6-Ku70 (pET11aKu70, a generous gift from M. Lieber, [12]) was expressed in BL21(DE3)pLysS Rosetta E. coli cells grown in LB at 37ºC until the culture reached OD600 1.0 at which point cells were induced with 1 mM IPTG for 4 hours at 37ºC. Crude lysate preparation and Talon affinity chromatography were carried out as described above. The eluted protein was loaded directly onto a 1 ml Hi-Trap Q (GE) column that had been equilibrated in R buffer with 50 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA and 1 mM DTT and eluted with a 50 mM to 1 M NaCl gradient in R buffer. Peak fractions were subject to gel purification to isolate Ku70, which was used to immunize two New Zealand White Rabbits (Covance). Rabbits were initially injected with 250 μg of Ku70, boosted 5 times over the course of 3 months with 125 μg per boost and production bleeds were collected. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against Ku80 were purchased (Serotec).

Results and Discussion

Expression and purification of recombinant Ku

Attempts to express individual Ku subunits (Ku70 and Ku80) in E. coli BL21(DE3) were unsuccessful and full-length polypeptides were not observed (data not shown). Expression of Ku70 was successful in BL21(DE3)pLysS Rosetta E. coli, which compensates for sub-optimal codon usage, and we were able to express and purify Ku70 with an average yield of 3 mg/L of original culture (data not shown). Expression of Ku80 in BL21(DE3)pLysS Rosetta E. coli cells resulted in insoluble protein (data not shown). Co-expression of Ku70 and Ku80 from separate plasmids resulted in insoluble Ku80 and monomeric, full-length, soluble Ku70 (data not shown). Co-expression of Ku70 and Ku80 from the same plasmid using independent promoters to drive expression of the Ku subunits resulted in full-length, soluble Ku70 and soluble Ku80 that had undergone substantial proteolysis (data not shown). We believe that failure of the Ku subunits to heterodimerize caused insolubility and proteolysis of Ku80 [11].

When a single T7 promoter was used to drive bicistronic expression of untagged Ku70 and his6-tagged Ku80 (expression vector pET70H80) in BL21(DE3)pLysS Rosetta E. coli we obtained soluble, full-length, heterodimerized recombinant Ku (rKu) (Fig. 2, top). Recombinant Ku was purified from E. coli lysate in a 2-step process described in Materials and Methods. Because Ku is a non-specific DNA binding protein metal-chelating affinity chromatography was carried out in high salt (1 M NaCl, 0.4 M (NH)4OAc), which prevented Ku-DNA interaction and minimized co-purification of both DNA and E. coli DNA-binding proteins. Addition of 0.4 M (NH)4OAc not only decreased co-purification of unwanted proteins but increased yield during the metal-chelating affinity chromatography step by approximately 2-fold. Full-length untagged- Ku70 and full-length his6-Ku80 co-eluted (Fig. 2), which indicated heterodimerization of the Ku subunits.

Elution from the metal-chelating resin in low salt enabled direct binding to heparin-agarose without the need for dialysis. Recombinant Ku bound well to heparin-agarose and all of the observed contaminating proteins flowed through the column, making elution by step-gradient possible (Fig. 2). While rKu eluted from heparin-agarose at ~0.4 M NaCl, step-gradient elution with 1 M NaCl allowed collection of maximum concentration in minimum volume. Recombinant Ku was dialyzed to reduce NaCl concentration for storage. A summary of the purification, which yielded 0.47 mg of rKu per L of original culture, is presented in Table 1. The low yield of this expression and purification system is likely the result of misfolding of Ku70 and Ku80. Western blot analysis using polyclonal antibodies directed against Ku70 and Ku80 showed that after sonication 25% of the total Ku70 and 20% of the total Ku80 are in the soluble fraction (data not shown). The insoluble fraction was found to contain both full length and proteolytic fragments of Ku70 and Ku80 (data not shown). Interestingly, only full-length Ku70 and Ku80 are found in the soluble fraction (data not shown). These data suggest that formation of the Ku70/80 heterodimer, and not expression of the full-length polypeptides, is the most likely cause of low yield in this system.

Table 1.

Purification of recombinant Ku from E. coli.

| Purification step | Total protein (mg) | rKu (mg) | Fold purification | Yield (%) | Purity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial lysate | 1251 | 1.62 | -- | -- | 1.28 |

| Talon Metal Chelating (Cobalt) | 11 | 0.942 | 125 | 60 | 93.8 |

| Hi-trap Heparin | 0.471 | 0.47 | 2.14 | 29.4 | ~100 |

Purification steps and estimated yield from 1g of wet weight cells.

-- does not apply;

determined by Bradford analysis;

estimated by western blot

DNA binding and activation of DNA-PK by recombinant Ku

DNA-PK plays an important role in mammalian NHEJ (Fig. 1) [7]. As the DNA-binding subunit of DNA-PK, Ku plays an especially important role in protecting the exposed DNA ends and regulating the protein kinase activity of DNA-PKcs. To assess the quality of our E. coli expressed rKu we examined the double-strand (ds) DNA-binding activity of rKu in an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

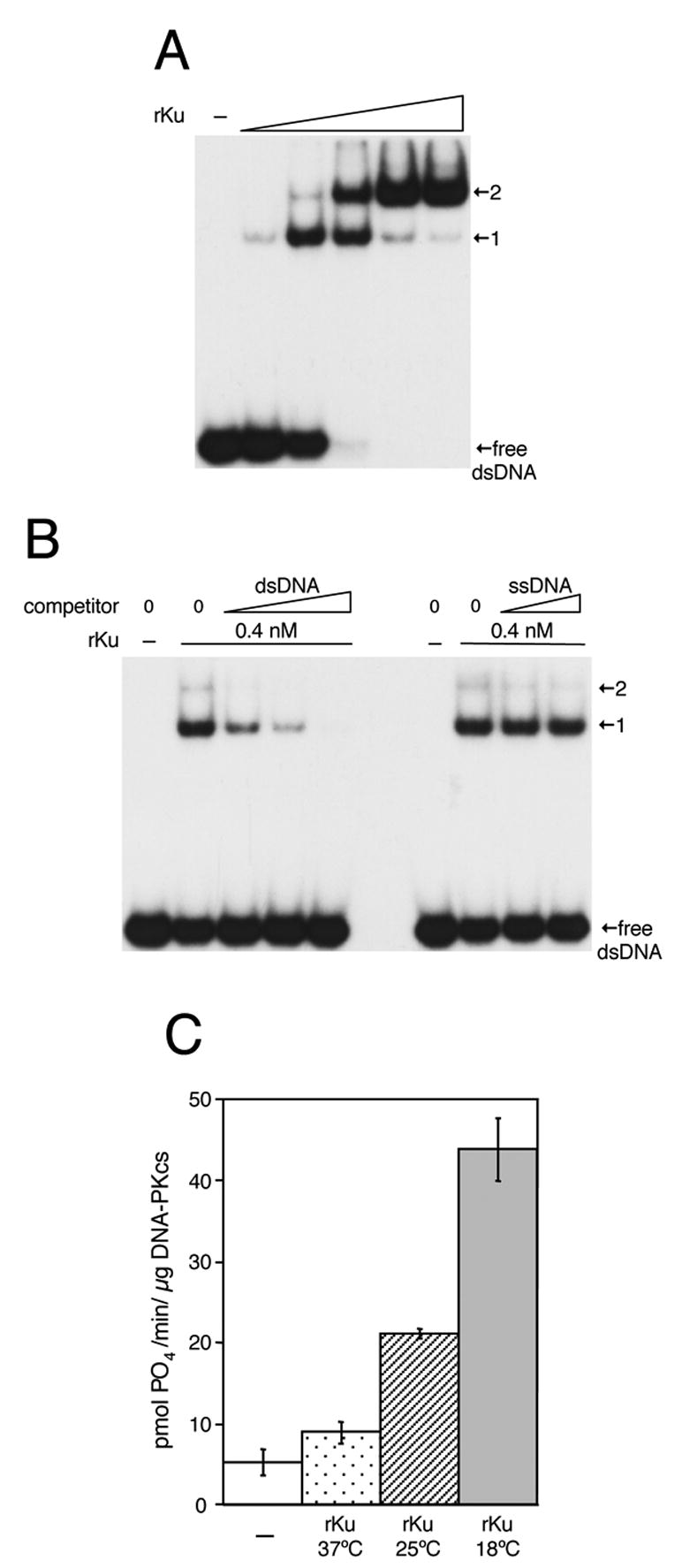

As shown in Fig. 3A, binding of rKu to the 48 bp substrate resulted in the step-wise formation of 2 distinct complexes with reduced electrophoretic mobility. Complex 1 is thought to result from binding of a single rKu to the dsDNA, while complex 2 is likely to contain 2 rKu per 48 bp duplex. Ku is thought to require a minimum of 20–25 bp for stable binding, and loading of multiple Ku molecules onto longer strands of duplex DNA has been observed [16]. It is worth noting that Figure 3A shows that at 7.7 nM Ku all of the 5 nM labeled DNA substrate has been bound, suggesting that a high percentage of the rKu is DNA-binding active.

Fig. 3.

Recombinant Ku binds dsDNA and activates DNA-PK. A) EMSA analysis of rKu binding to dsDNA using 5 nM radiolabeled dsDNA. A) dsDNA binding by rKu at 0.9, 2.6, 7.7, 23 and 69 nM. B) rKu binding in the presence of dsDNA (1.25, 5 and 20 nM) or ss DNA (50 and 200 nM). C) Activation of DNA-PK by rKu purified from cultured induced to express rKu at 37ºC, 25ºC or 18ºC. (−) indicates no rKu.

Duplex DNA acts as an efficient competitor for rKu binding (Fig. 3B, left), which is abolished by the addition of 4-fold molar excess of unlabeled dsDNA. In contrast, single-stranded (ss) DNA is unable to compete for rKu binding as even a 40-fold molar excess of unlabeled ssDNA had no effect on rKu binding to the labeled dsDNA binding substrate (Fig. 3B). E. coli produced rKu was able to bind dsDNA cellulose prepared with calf thymus DNA (data not shown), which indicated a lack of sequence specificity in DNA recognition. Finally, covalently closed circular plasmid DNA did not act as an effective competitor for rKu binding (data not shown), which is consistent with the requirement of DNA ends for Ku binding. Taken together these data demonstrate that rKu produced in E. coli exhibits binding to dsDNA, regardless of DNA sequence, and that this binding requires accessible DNA termini. These findings are consistent with observations made with Ku purified from mammalian cells and further indicate that rKu produced in E. coli is properly folded and suitable for biochemical assays.

Having established that Ku is able to bind dsDNA we next examined the ability of rKu to activate DNA-PK. Expression of recombinant proteins in E. coli at low temperatures has been shown to improve protein stability. As shown in Fig. 3C, the temperature at which rKu was expressed had a significant impact on activation of DNA-PK. Preparations of rKu purified from cultures induced at 37ºC, 25ºC or 18ºC were used in DNA-PK activation assays and maximum activity was observed with rKu purified from cells induced at 18ºC. Control reactions carried out in the absence of either rKu or dsDNA demonstrated that both species were required for efficient activation of DNA-PK (data not shown). Data presented in Fig. 3 show that rKu produced in E. coli has the ability to recognize dsDNA and activate DNA-PK.

E. coli produced rKu can participate in NHEJ in vitro

Ku-dependent mammalian NHEJ can be examined biochemically using whole cell extracts (WCE) prepared from cultured human cells [14] (Fig. 4). To be useful in the study of Ku in mammalian NHEJ it is crucial that rKu function in this in vitro NHEJ assay system. To determine if E. coli produced rKu is fully functional we carried out complementation analysis using Ku-depleted WCE. Anti-Ku antibodies were used to deplete endogenous Ku from HeLa WCE in the presence of 0.5 M NaCl. Immunodepletion of Ku under low-salt (0.1 M KOAc) conditions resulted in Ku-depleted WCE that was unable to carry out NHEJ in vitro and could be complimented by the immunoprecipitate, but could not be complemented by Ku purified from HeLa cells (Fig. 4A). Because Ku is thought to participate in protein-protein interactions with other NHEJ factors it is likely that under conditions of low ionic strength that Ku is associating with, and co-immunodepleting, factors important for NHEJ. Immunodepletion of Ku under conditions of high ionic strength (0.5 M NaCl (high-salt)) resulted in Ku-depleted WCE that could be complimented by both the immunoprecipitate and by Ku purified from HeLa cells (Fig. 4B). The increased salt was thought to abrogate protein-protein interactions with Ku and minimize depletion of NHEJ factors.

Fig. 4.

E. coli produced rKu participates in NHEJ in vitro. A) Whole cell extract (WCE; lane 1) and low salt Ku-depleted WCE (LS Ku-dep WCE; lanes 2 – 8) were prepared and NHEJ reactions were carried out as described in Materials and Methods. 1, 2 or 3 μl of the immunoprecipitate was used to complement low salt Ku-depleted WCE (IP; lanes 3 – 5). Ku purified from HeLa cells was used at 12.8, 38.4 and 115.2 nM (HeLa Ku; lanes 6 – 8). B) High salt Ku-depleted WCE (HS Ku-dep WCE; lanes 3 – 7) was used in NHEJ reactions. 3 μl of the immunoprecipitate was used to complement high salt Ku-depleted WCE (IP; lane 4). Ku purified from HeLa cells was used as in (A) (HeLa Ku; lanes 5 – 7). C) High salt Ku-depleted WCE (HS Ku-dep WCE; lanes 3 – 12) was used in NHEJ reactions. Recombinant Ku (rKu) was used at 140 nM. Anti-XRCC4 antibody (a-XRCC4; 1:6250, 1:1250, 1:250 and 1:50; lanes 5 – 8) and Wortmannin (wort; 0.3, 1.0 and 3.0 μM; lanes 10 – 12) were added where indicated. (−) indicates no treatment

Addition of bacterially produced recombinant Ku to high salt Ku-depleted WCE restored in vitro NHEJ (Fig. 4C, lanes 4 and 9). To characterize the observed rKu-complemented ligation activity, end-joining was assayed in the presence of neutralizing anti-XRCC4 antibodies or in the presence of low concentrations of wortmannin (an inhibitor of DNA-PKcs and other PI3K-related protein kinases). Treatment with either anti-XRCC4 antibodies or wortmannin resulted in a significant decrease in ligation efficiency (Fig. 4C), which indicated a requirement for both XRCC4 and DNA-PKcs and identified the observed end-joining as bona fide mammalian NHEJ. Taken together these data demonstrate that recombinant Ku produced in E. coli is fully functional, can participate in mammalian NHEJ in vitro and can be used to study the role of Ku in mammalian NHEJ.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Ku heterodimer is known to play an important role in mammalian DNA repair. Structurally, Ku is unusual in that heterodimerization of the Ku70 and Ku80 subunits buries a large amount of surface area (~9000Å2 [1]). Perhaps as a result of the extensive interfacial surface, we found that soluble Ku could not be produced by independently expressing the two subunits. However, it was possible to express recombinant Ku (rKu) in E. coli using a bicistronic expression system. Purification of rKu was straightforward (Fig. 2). Purified rKu was found to have biologically relevant activity in that it bound dsDNA and activated the DNA-dependent protein kinase DNA-PK (Fig. 3). Most importantly purified rKu complemented DNA end-joining in Ku-depleted extracts in vitro (Fig. 4C). These data indicate that E. coli produced rKu is suitable for use in the biochemical analysis of mammalian NHEJ.

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Briones, J. Cheung, Y. Dwarka, A. Gallop and B.T. Rantipole for technical assistance and Dr. B. Russ for critical reading of this manuscript. This work was supported by the Maryland Cigarette Restitution Fund, the Rita Allen Foundation and the National Institutes of Health Grant GM070639-1.

Abbreviations used

- DSB

double strand break

- NHEJ

non-homologous end-joining

- DNA-PK

DNA-dependent protein kinase

- rKu

recombinant Ku

- WCE

whole cell extract

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Walker JR, Corpina RA, Goldberg J. Structure of the Ku heterodimer bound to DNA and its implications for double-strand break repair. Nature. 2001;412:607–614. doi: 10.1038/35088000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferguson DO, Alt FW. DNA double strand break repair and chromosomal translocation: Lessons from animal models. Oncogene. 2001;20:5572–5579. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoeijmakers JH. Genome maintenance mechanisms for preventing cancer. Nature. 2001;411:366–74. doi: 10.1038/35077232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Critchlow SE, Jackson SP. DNA end-joining: from yeast to man. TIBS. 1998;23:394–398. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buck D, Malivert L, de Chasseval R, Barraud A, Fondaneche MC, Sanal O, Plebani A, Stephan JL, Hufnagel M, le Deist F, Fischer A, Durandy A, de Villartay JP, Revy P. Cernunnos, a novel nonhomologous end-joining factor, is mutated in human immunodeficiency with microcephaly. Cell. 2006;124:287–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahnesorg P, Smith P, Jackson SP. XLF interacts with the XRCC4-DNA ligase IV complex to promote DNA nonhomologous end-joining. Cell. 2006;124:301–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith GCM, Jackson SP. The DNA-dependent protein kinase. Genes Dev. 1999;13:916–934. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.8.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharpless NE, Ferguson DO, O'Hagan RC, Castrillon DH, Lee C, Farazi PA, Alson S, Fleming J, Morton CC, Frank K, Chin L, Alt FW, DePinho RA. Impaired nonhomologous end-joining provokes soft tissue sarcomas harboring chromosomal translocations, amplifications, and deletions. Mol Cell. 2001;8:1187–1196. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00425-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ono M, Tucker PW, Capra JD. Production and characterization of recombinant human KU antigen. Nucl Acids Res. 1994;22:3918–3924. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.19.3918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ponstingl H, Kabir T, Gorse D, Thornton JM. Morphological aspects of oligomeric protein structures. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2005;89:9–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lo Conte L, Chothia C, Janin J. The atomic structure of protein-protein recognition sites. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:2177–98. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu XT, Lieber MR. Protein-protein and protein-DNA interaction regions within the DNA end-binding protein Ku70-Ku86. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5186–5193. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.5186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanakahi LA, West SC. Specific interaction of IP6 with human Ku70/80, the DNA-binding subunit of DNA-PK. EMBO J. 2002;21:2038–2044. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.8.2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baumann P, West SC. DNA end-joining catalyzed by human cell-free extracts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14066–14070. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanakahi LA, Bartlet-Jones M, Chappell C, Pappin D, West SC. Binding of inositol phosphate to DNA-PK and stimulation of double-strand break repair. Cell. 2000;102:721–729. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paillard S, Strauss F. Analysis of the mechanisms of interactions of simian Ku protein with DNA. Nucl Acids Res. 1991;19:5619–5624. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.20.5619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kysela B, Doherty AJ, Chovanec M, Stiff T, Ameer-Beg SM, Vojnovic B, Girard PM, Jeggo PA. Ku stimulation of DNA ligase IV-dependent ligation requires inward movement along the DNA molecule. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:22466–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303273200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]